Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer remains the most

devastating gynecologic cancer. Although 40–60% of patients achieve

complete clinical responses to first-line chemotherapy treatment,

~50% of these patients relapse within 5 years; only 10–15% of

patients who present with advanced disease achieve long-term

remission (1,2). The standard of care for first-line

chemotherapy treatment is paclitaxel in combination with a

platinum-based compound, or platinum-based therapy alone (3). Chemotherapy induces significant side

effects and has limited efficacy, such as drug resistance and rapid

recurrence, respectively, which subsequently reduce patient

survival rates (4,5). Hence, more effort is needed to

understand the mechanisms of drug resistance to anticancer drugs.

Resistance to chemotherapy for ovarian cancer potentially involves

several mechanisms (6).

P-glycoprotein, which is encoded by the gene, multiple drug

resistance 1 (MDR1), functions as a transmembrane efflux

pump for the elimination and disposition of xenobiotics, including

the anticancer drugs paclitaxel and cisplatin, which implies a

major role in multidrug resistance (7). MDR1 over-expression in certain

tumor cells has been associated with protection against anticancer

agents (8). Therefore, altering

MDR1 expression could improve the patient’s clinical outcome

(9–11).

Pregnane X receptor (PXR), a member of the nuclear

receptor superfamily, has been shown to mediate the genomic effects

of several steroid hormones, including progesterone, pregnenolone,

and estrogen, and of xenobiotics (12–18).

PXR regulation involves a specific DNA sequence, the PXR-responsive

element, which is found in various genes, including the upstream

region of the cytochrome (P450) 3A (CYP3A) gene family

(12,14,17),

which codes for monooxygenases responsible for the oxidative

metabolism of certain endogenous substrates and xenobiotics

(19,20), and MDR1 (21,22).

Because the PXR pathway is activated by a large number of

prescription drugs designed to treat infection, cancer, convulsion,

and hypertension (23), PXR is

thought to play roles in drug metabolism/efflux and drug-drug

interaction. For example, PXR activation is reportedly involved in

regulating cell cycle proliferation and apoptosis inhibition

(24–27). PXR was previously shown as a

possible prognostic factor that might feasibly identify patients at

risk of recurrence or death from epithelial ovarian cancer

(28), however, PXR function in

ovarian cancer remains unknown, especially in combination with

anticancer drugs. Paclitaxel and cisplatin, which are widely used

as first-line chemotherapy drugs in ovarian cancer (3–5),

could act as PXR ligands (29).

In addition, we previously showed that

downregulating the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) through

RNA interference significantly promoted cell growth inhibition and

enhancement of apoptosis in the presence of anticancer agents,

paclitaxel and cisplatin (30).

CAR as well as PXR is activated by a variety of endogenous and

exogenous ligands including drugs, insecticides, pesticides, and

nutritional compounds (31) and

functions as a xenobiotic receptor that regulates detoxification

and clearance of xenobiotics (32). Therefore, both PXR and CAR might

play some roles in drug resistance.

We therefore examined the effects of combining a

ligand and antagonist for PXR with anticancer drugs on ovarian

cancer cells, and the potential contribution of PXR downregulation

by RNA interference toward increasing drug sensitivity and

overcoming drug resistance in this study. We also examined the

relationship of PXR with another xenobiotics receptor CAR in the

drug resistance function for ovarian cancer.

Materials and methods

Materials

Phthalic acid bis (2-ethylhexel ester) (phthalate),

5-pregneno-3β-ol-20-one (pregnenolone), ketoconazole, paclitaxel,

cisplatin, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Each drug was dissolved in DMSO

and stored at −20°C before use. The final concentration of DMSO was

0.1%; 0.1% DMSO was used for the negative control.

Cell culture

Ovarian cancer cell lines, SKOV-3, OVCAR-3, CaOV-3,

and BG-1 cells, and human hepatoma cell line, HepG2 cells were

obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka,

Japan). These ovarian cancer cell lines were derived from patients

with ovarian adenocarcinoma. SKOV-3 cells and CAOV-3 were from

patients previously treated with chemotherapy, BG-1 cells from an

untreated patient, and OVCAR-3 cell line from a patient who did not

respond to chemotherapy (33).

SKOV-3 and OVCAR-3 cells have been shown to be relatively resistant

to platinum and taxanes, BG-1 cells to be resistant to platinum,

and CAOV-3 to be sensitive to both platinum and taxanes (33,34).

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal

bovine serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel)

and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were

cultured under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at

37°C.

Quantitative real-time

reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit

(Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol,

then stored at −80°C. The concentration and purity of isolated RNA

was determined using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific

Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed using

the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit with RNA inhibitor

(Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Complementary DNA was

obtained through the GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems).

cDNA isolated from each of the different drug groups was analyzed

by real-time PCR using TaqMan universal master mix containing

different primers (Applied Biosystems). Primers for MDR1, CYP3A4,

and PXR (Applied Biosystems) were normalized to the 18S

housekeeping gene. After 50 cycles, mRNA expression was calculated

by the comparative CT-value method. The negative control was 0.1%

DMSO.

Transient transfection studies

The (CYP3A4)3-tk-chloramphenicol acetyl

transferase (CAT) was generated by inserting three copies of

double-strand oligonucleotides containing the CYP3A4

(5′-GGGTCAGCAAGTTCA-3′). The (MDR1)3-tk-CAT was

generated by inserting three copies of a double-strand

oligonucleotide containing the MDR1 (5′-AGGTCAAGTTAGTTCA-3′) as

described before (29). CaOV-3

cells were transfected with 1μg of a reporter gene construct

[(CYP3A4)3-tk-CAT or (MDR1)3-tk-CAT]. In all

experiments, liposome-mediated transfections used Lipofectamine

(Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were treated with

DMSO alone or with anticancer drugs paclitaxel (5 μM), cisplatin

(10 μM), PXR ligands pregnenolone (10 μM) or phthalate (10 μM),

with or without RNA interference for 36 h. Cell extracts were

prepared and assayed for CAT activity. Amount of CAT was determined

using a CAT ELISA Kit (Roche Diagnostics Co., Tokyo, Japan)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA interference

The siRNA cocktail targeting human PXR (cat. no.

sc-44057), human CAR (cat. no. sc-39918), and negative control

cocktail (cat. no. sc-37007), which consists of a scrambled

sequence that does not lead to the specific degradation of any

cellular message, were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology

(Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Cells were transfected with PXR siRNA, CAR

siRNA or control siRNA using the siRNA Reagent system (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

MTT assay

Cells were plated 5×103 in a 96-well

plate in at least triplicate samples for each experimental

condition. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with

anticancer drugs paclitaxel (5 μM) or cisplatin (10 μM) with or

without RNA interference or in the presence or absence of

pregnenolone or ketoconazole for 24, 48 and 72 h. We used a

commercial MTT cell proliferation kit (Bioassay Systems, Hayward,

CA, USA) and followed its instructions. After each incubation time,

15 μl 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

(MTT) was added into each well. After a 4-h incubation at 37°C, 150

μl solubilization solution was added to each well and the plate was

gently agitated for 1 h at room temperature. Absorbance was

measured at 595 nm using an Imark microplate reader (Bio-Rad,

Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was examined using a terminal

deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

(TUNEL) assay that employed the ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ

Apoptosis Detection kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA)

following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were grown on

sterilized glass coverslips in a 6-well culture plate overnight,

and then exposed to the different experimental drug groups. Cells

were then stained and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium in

the presence of the nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

(DAPI). Afterwards, TUNEL- and DAPI-positive cells were counted

using fluorescence microscopy. The ratio of TUNEL-positive to

DAPI-positive cells was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed as one-way

analysis of variance with post-hoc testing analysis and the

Student’s t-test using SPSS Statistics 19.0 software (IBM, Armonk,

NY, USA). All data are expressed as mean ± SD. P<0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

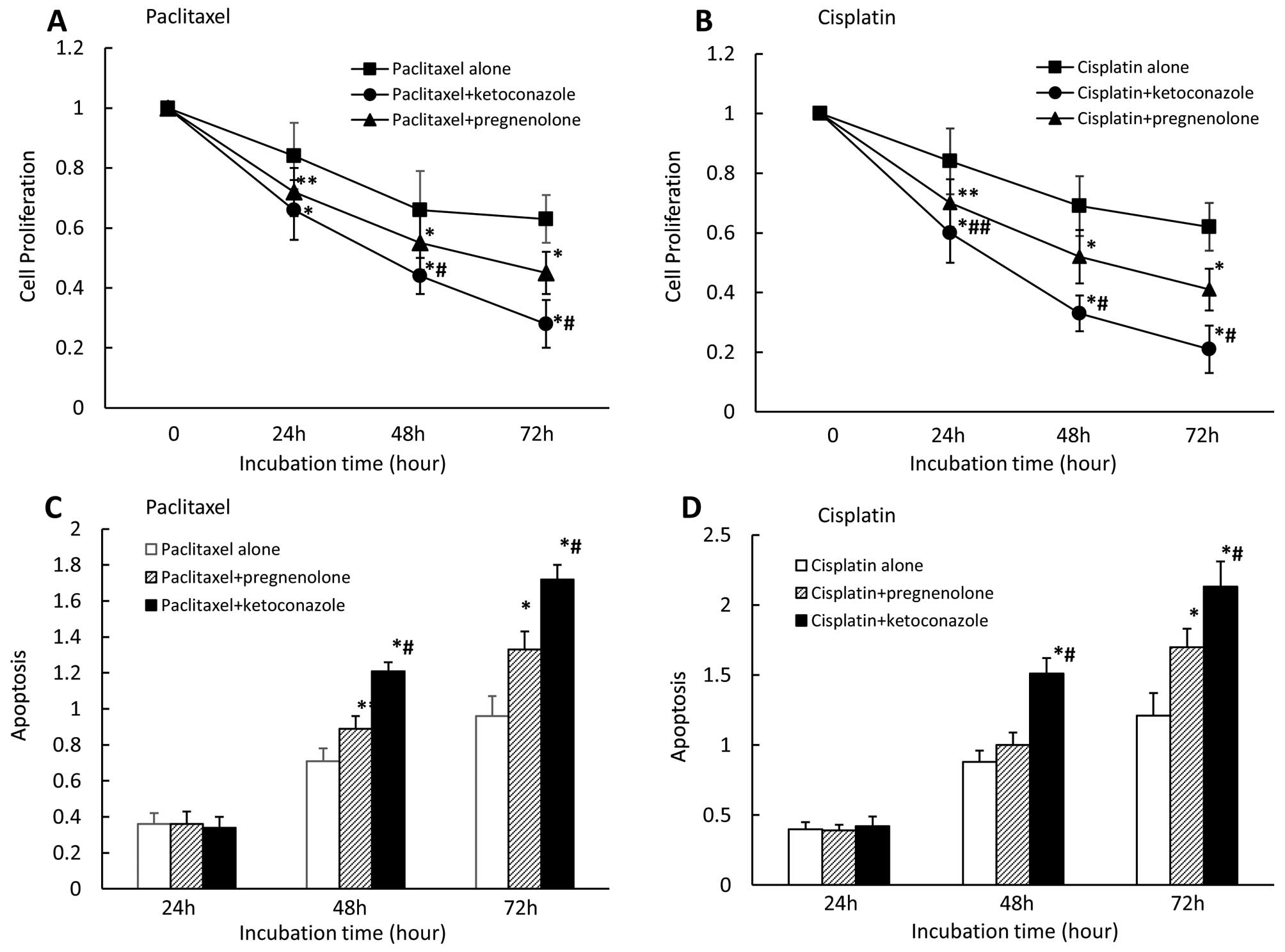

Effect of paclitaxel and cisplatin on

MDR1 and CYP3A4 mRNA expression and PXR-mediated transcription in

ovarian cancer cell lines

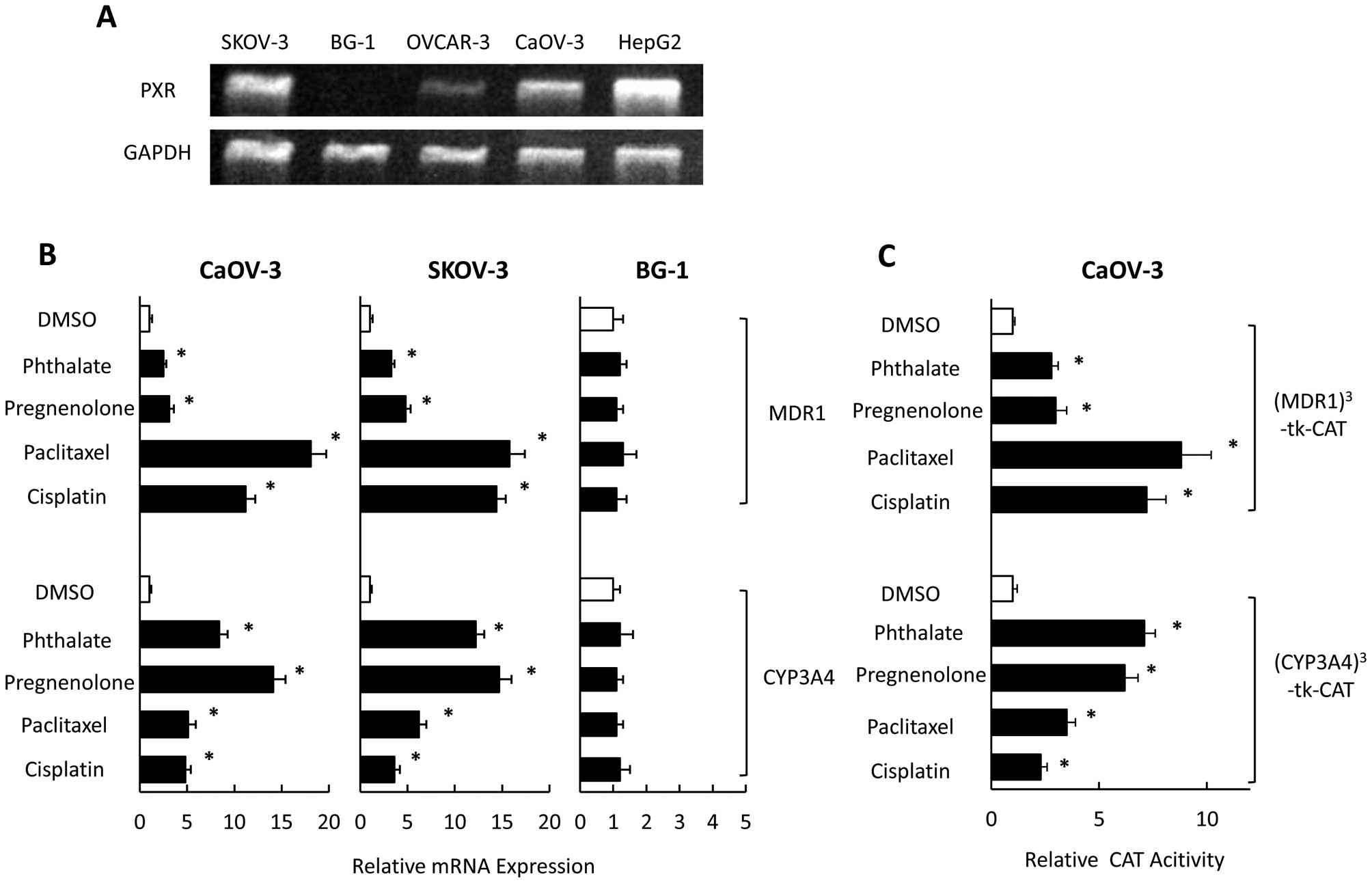

Expression of PXR has been reported in SKOV-3 and

OVCAR-8 ovarian cancer cells (27). We examined PXR expression in

OVCAR-3, CaOV-3, SKOV-3 and BG-1 cells using RT-PCR. PXR was

strongly expressed in SKOV-3 and CaOV-3 cells, moderately expressed

in OVCAR-3 cells, and not expressed in BG-1 cells (Fig. 1A). To investigate the effect of PXR

ligands (including anticancer drugs) on expression of CYP3A4 and

MDR1 in vitro, we examined mRNA levels of CYP3A4 and MDR1 in

SKOV-3, CaOV-3, and BG-1 cells that had been exposed to

pregnenolone, phthalate, paclitaxel, and cisplatin, which could

activate PXR-mediated transcription through CYP3A4 and MDR1

promoters (28). In SKOV-3 and

CaOV-3 cells, CYP3A4 mRNA levels were significantly increased in

the presence of PXR ligands (Fig.

1B). Pregnenolone and phthalate had significantly positive

effects on CYP3A4 expression compared with paclitaxel or cisplatin.

In contrast, the MDR1 level was significantly and strongly

increased in the presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin compared with

pregnenolone and phthalate. MDR1 and CYP3A4 levels did not change

in response to any PXR ligands in BG-1 cells (which did not express

PXR). PXR ligands also enhanced PXR-mediated transcription through

both MDR and CYP3A4 promoters in CaOV-3 cells (Fig. 1C). Paclitaxel and cisplatin had

significant effects on PXR-mediated transcription through the MDR

promoter compared with pregnenolone and phthalate. In contrast,

pregnenolone and phthalate strongly enhanced PXR-mediated

transcription through CYP3A4 promoter compared with paclitaxel or

cisplatin.

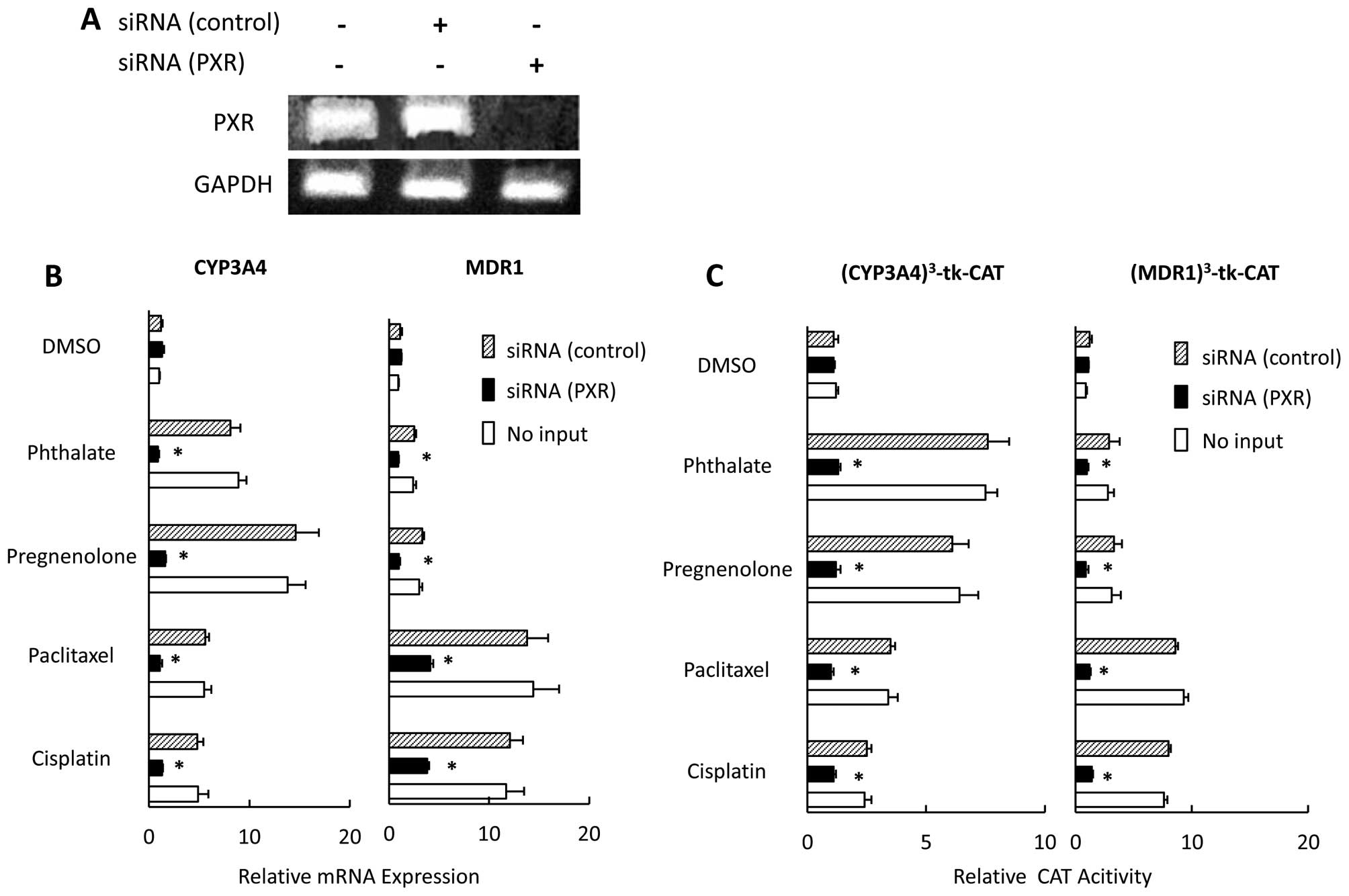

| Figure 1Effect of anticancer drugs on the

mRNA expression of MDR1 and CYP3A4 and PXR-mediated transcription

in ovarian cancer cell lines. The expression of PXR and

GAPDH mRNAs were analyzed using RT-PCR in ovarian cancer

cell lines, SKOV-3, BG-1, OVCAR-3, and CaOV-3 (A). CaOV-3, SKOV-3,

and BG-1 cells were treated with pregnenolone, phthalate,

paclitaxel, cisplatin, or DMSO for 24 h and analyzed for the mRNA

expression using quantitative real-time PCR (B). CaOV-3 cells were

cotransfected with reporter gene constructs,

(MDR1)3-tk-CAT or (CYP3A4)3-tk-CAT and

treated with pregnenolone, phthalate, paclitaxel, cisplatin, or

DMSO for 36 h. CAT levels were determined by an ELISA kit (C).

Results show mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments

(*P<0.01 vs. DMSO group). |

Effect of PXR siRNA on MDR1 and CYP3A4

mRNA expression and PXR-mediated transcription in CaOV-3 cells

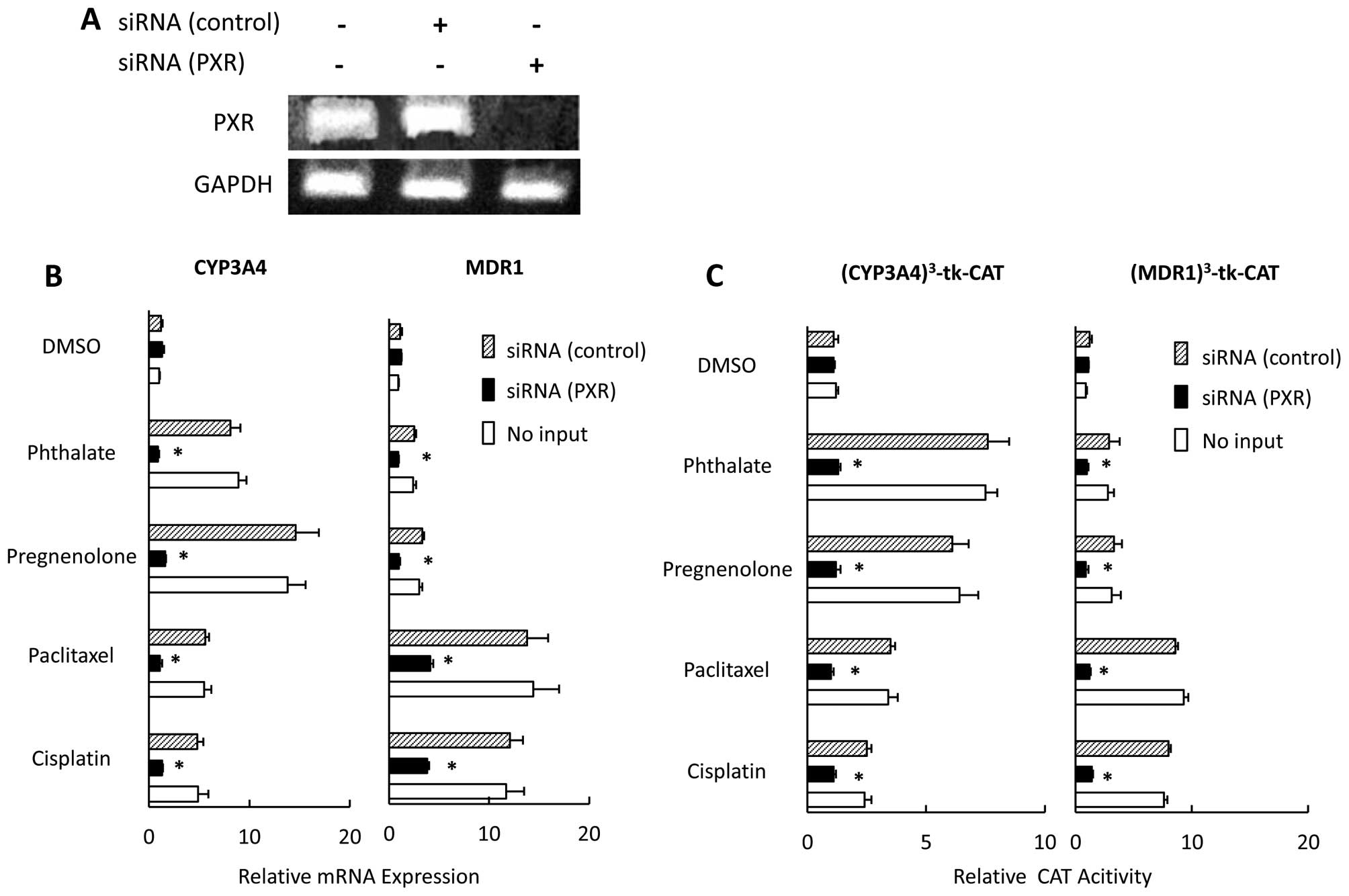

We examined the effect of downregulating PXR by

using siRNA on expression of MDR1 and CYP3A4, and PXR-mediated

transcription in the presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin in CaOV-3

cells. First, we used RT-PCR to confirm that PXR mRNA was not

detected in the PXR-siRNA transfected CaOV-3 cells (Fig. 2A). The effects of PXR ligands,

including paclitaxel and cisplatin, on MDR1 expression were

strongly inhibited in PXR siRNA-transfected cells, and we saw no

positive effects of PXR ligands on CYP3A4 expression in PXR

siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2B),

nor any non-specific effects of siRNA. PXR expression did not

significantly differ between cells treated with control siRNA and

those not treated with any siRNA (data not shown). We also examined

the effects of PXR siRNAs on PXR-mediated transcription. In control

siRNA-transfected cells, PXR ligands significantly activated native

PXR-mediated transcription; whereas the PXR siRNA-transfected cells

showed no PXR-mediated transactivation in the presence of PXR

ligands, including paclitaxel and cisplatin (Fig. 2C).

| Figure 2Effect of PXR siRNA on the

expression of MDR1 and CYP3A4 and PXR-mediated transcription in

CaOV-3 cells. CaOV-3 cells were transfected with PXR- or control

siRNA (A). CaOV-3 cells were transfected with PXR- or control siRNA

and treated with pregnenolone, phthalate, paclitaxel, cisplatin, or

DMSO for 36 h. CYP3A4 and MDR1 mRNA expression were

analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. Each experiment was

performed in triplicate, 4 times (internal control, 18S; negative

control, DMSO). Changes in gene expression were calculated as

ratios of target gene to internal control (B). CaOV-3 cells were

cotransfected with PXR- or control siRNAs, or no siRNA and a

reporter gene construct, (MDR1)3-tk-CAT or

(CYP3A4)3-tk-CAT; and then treated with pregnenolone,

phthalate, paclitaxel, cisplatin or DMSO for 36 h. CAT levels were

determined by ELISA (C). Results, mean ± SD of 5 independent

experiments (*P<0.01 vs. control siRNA group). |

Effect of PXR siRNA on cell proliferation

and apoptosis in CaOV-3 cells

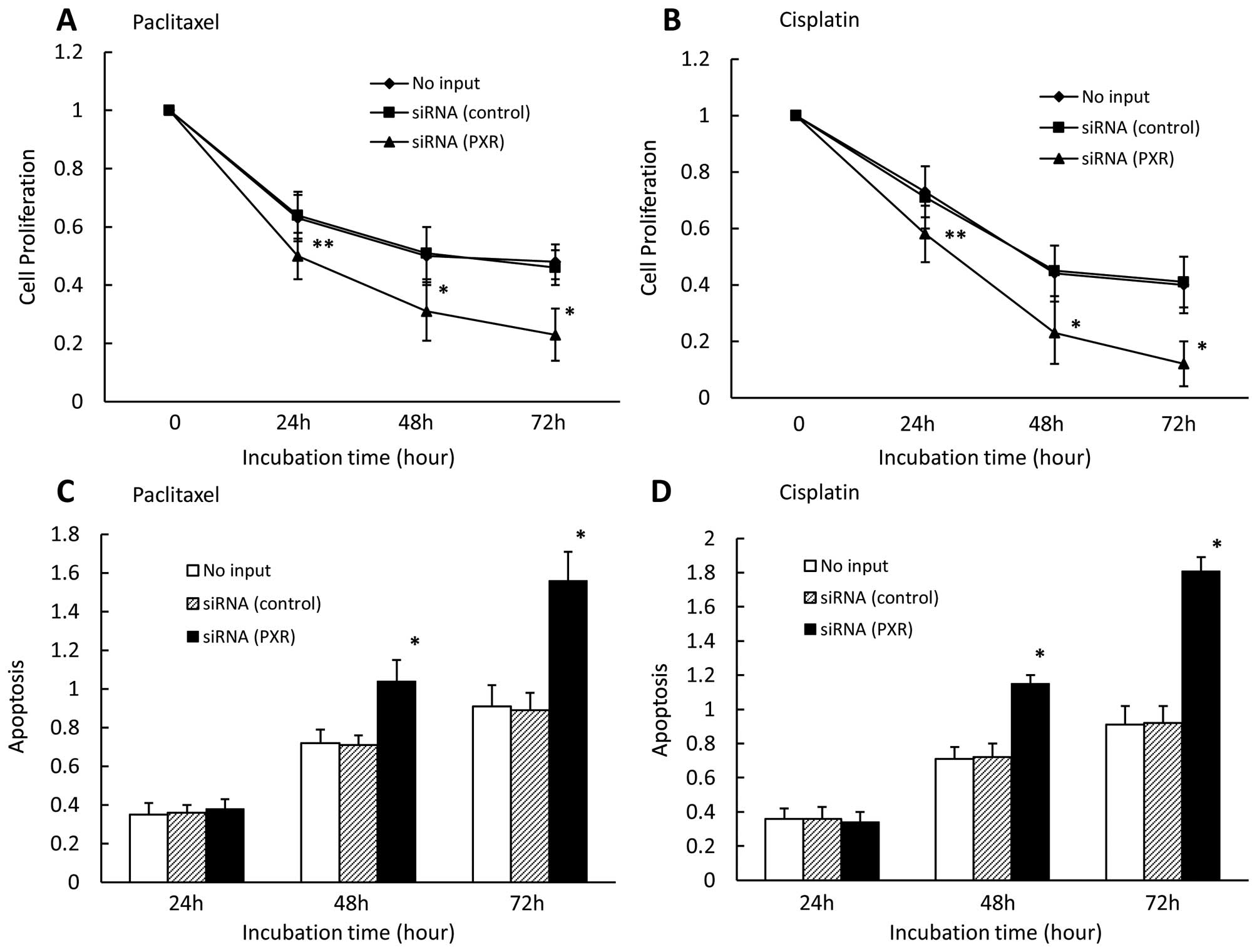

We also examined the effect of downregulated PXR on

cell proliferation and apoptosis in the presence of paclitaxel or

cisplatin in CaOV-3 cells. We found that down-regulated PXR

significantly enhanced cell growth inhibition in the presence of

paclitaxel (Fig. 3A) and cisplatin

(Fig. 3B) for 24, 48, and 72 h.

Cell growth did not significantly differ between control

siRNA-transfected cells and untransfected cells. We also observed

that downregulated PXR significantly enhanced apoptosis in PXR

siRNA-transfected cells compared with cells transfected with

control siRNA or without siRNA in the presence of paclitaxel

(Fig. 3C) and cisplatin (Fig. 3D) for 48 and 72 h. Apoptosis rates

did not significantly differ between control siRNA-transfected

cells and untransfected cells.

Effect of combining paclitaxel or

cisplatin with PXR ligand or antagonist on transcription of

PXR-related genes

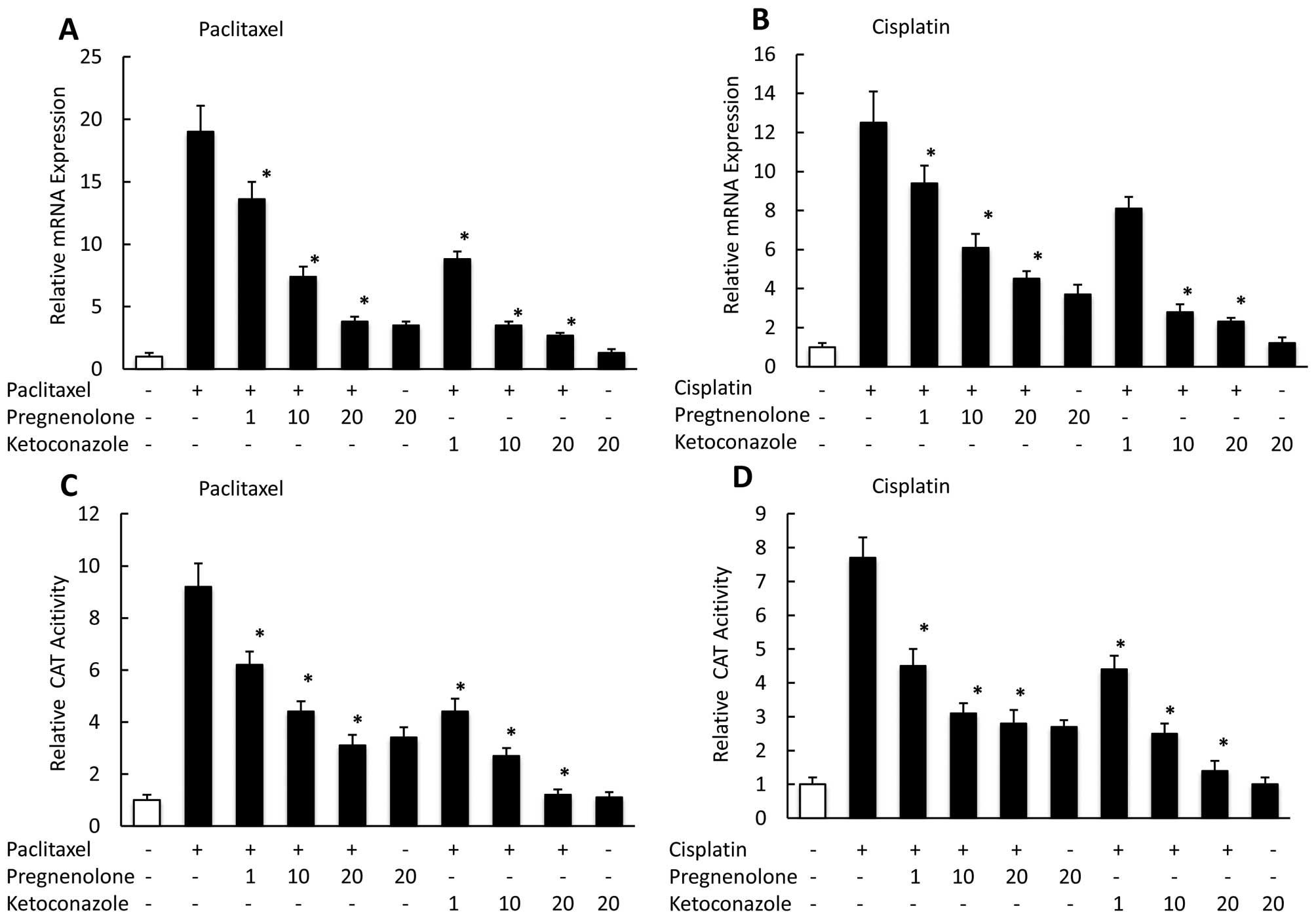

To determine the effect of treating CaOV-3 cells

with anticancer drugs in combination with the PXR agonist

pregnenolone, or the PXR antagonist ketoconazole on the PXR target

genes, MDR1 and CYP3A4, we used real-time PCR to assess their mRNA

expression levels at 24 h. We observed pregnenolone moderately

suppressed the MDR1 mRNA expression enhanced by paclitaxel or

cisplatin, whereas ketoconazole had a significant negative effect

on the MDR1 expression enhanced by paclitaxel (Fig. 4A) or cisplatin (Fig. 4B) in a dose-dependent manner. We

also examined the effect on PXR-mediated transcription of combining

paclitaxel or cisplatin with a PXR ligand or antagonist.

Pregnenolone suppressed PXR-mediated transac-tivation by paclitaxel

or cisplatin, whereas ketoconazole more strongly reduced

transcription in the presence of paclitaxel (Fig. 4C) and cisplatin (Fig. 4D) in a dose-dependent manner.

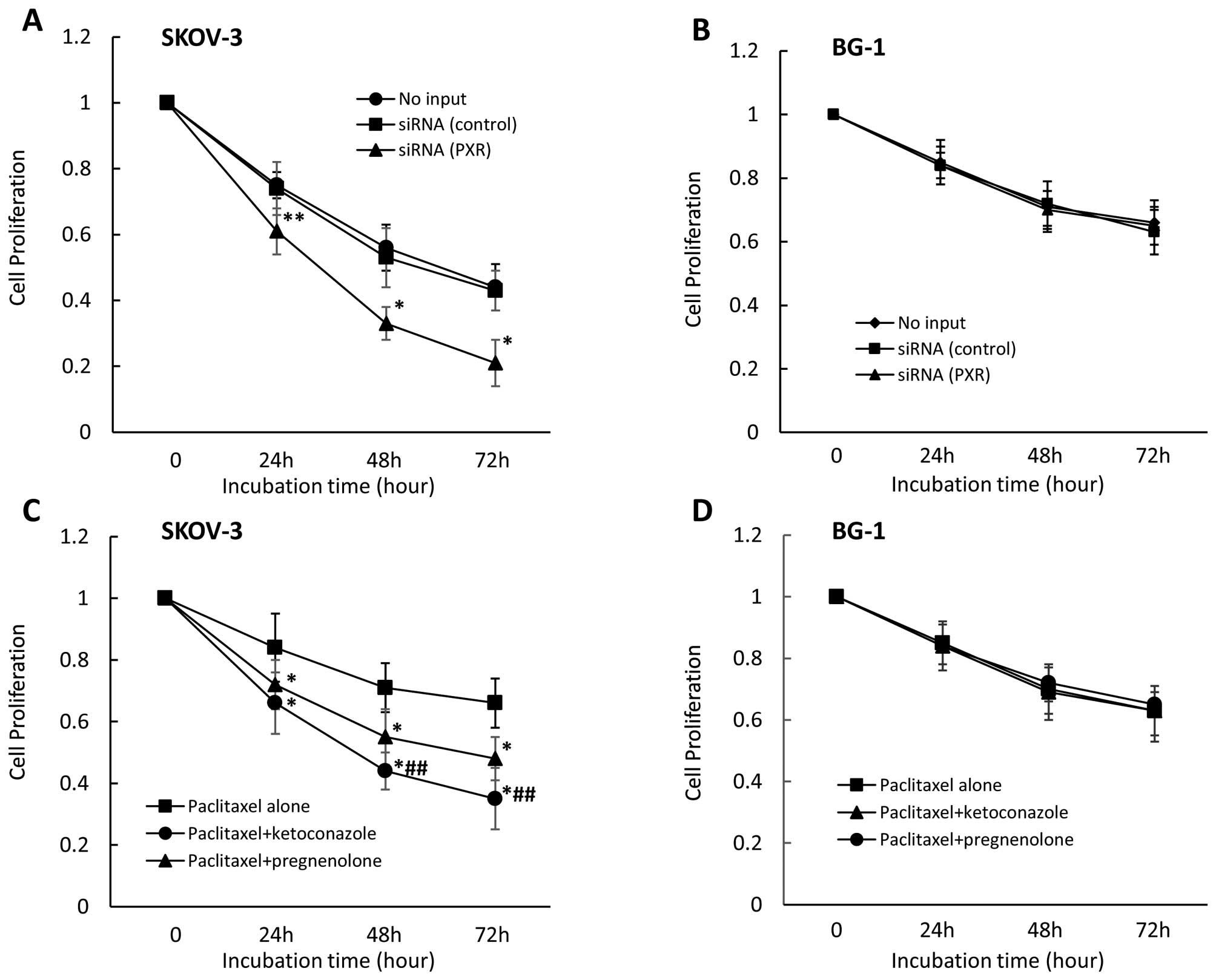

Effect of combining paclitaxel or

cisplatin with PXR ligand or antagonist on cell proliferation and

apoptosis in CaOV-3 cells

We also examined the effects of combining the

anticancer paclitaxel or cisplatin with the PXR ligand

pregnenolone, or the PXR antagonist ketoconazole on cell

proliferation and apoptosis. We found that pregnenolone

(moderately) and ketoconazole (strongly) enhanced cell growth

inhibition in the presence of paclitaxel (Fig. 5A) or cisplatin (Fig. 5B) after 24, 48 and 72 h. Cell

growth inhibition significantly differed between pregnenolone and

ketoconazole in the presence of paclitaxel for 48 and 72 h and

cisplatin for 24, 48 and 72 h. We also observed that pregnenolone

(moderately) and ketoconazole (strongly) enhanced apoptosis in the

presence of paclitaxel (Fig. 5C)

or cisplatin (Fig. 5D) after 48

and 72 h for either agent. Apoptosis rates significantly differed

between pregnenolone and ketoconazole in the presence of either

paclitaxel or cisplatin for 48 and 72 h for either agent.

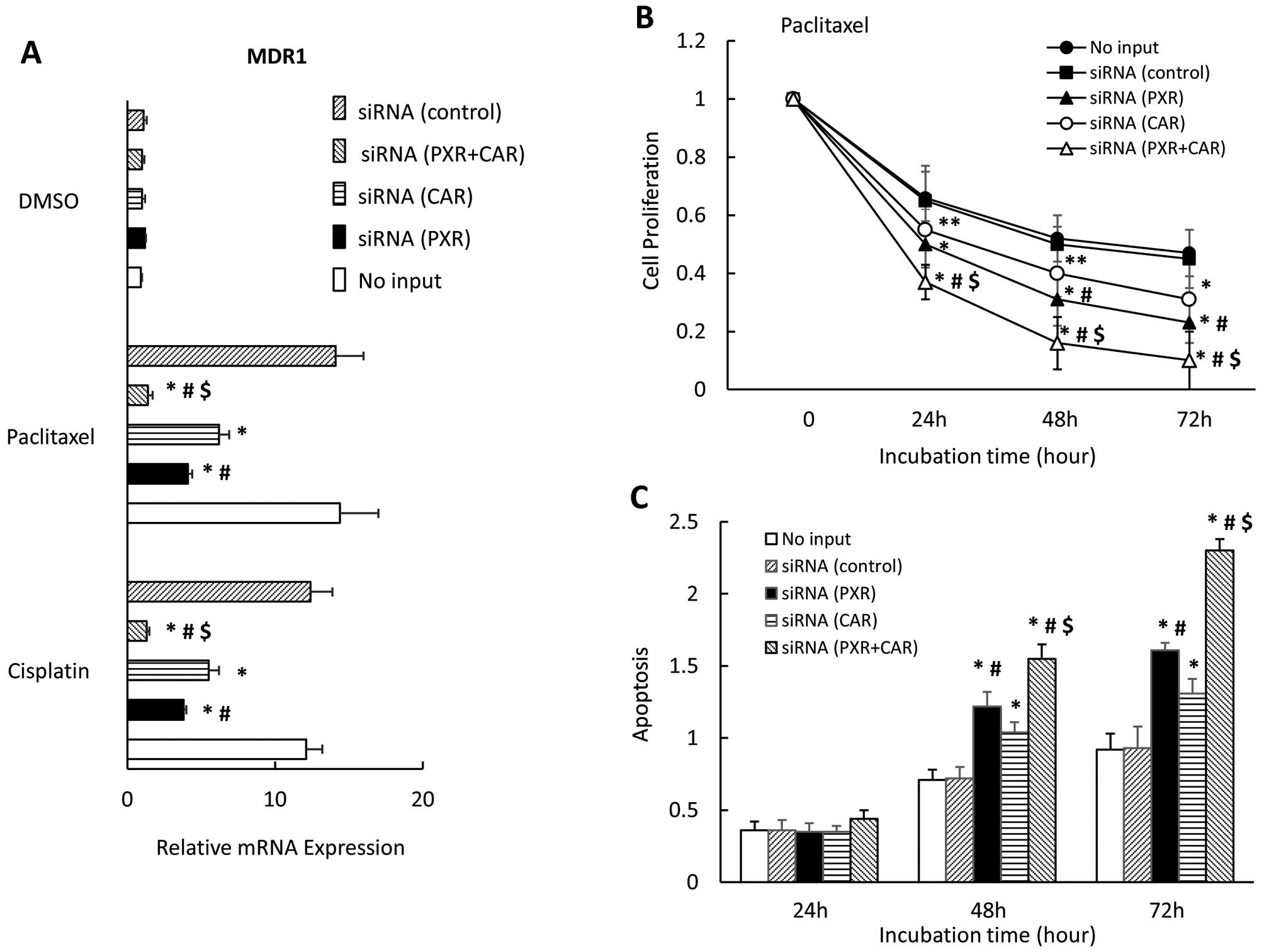

Effect of PXR siRNA and PXR ligand or

antagonist on cell proliferation in other ovarian cell lines

treated with paclitaxel or cisplatin

We also examined the effect of PXR downregulation on

cell proliferation in other ovarian cancer cell lines. We observed

that PXR downregulation significantly enhanced cell growth

inhibition in the presence of paclitaxel in SKOV-3 cells, which

strongly express PXR (Fig. 6A) but

not in BG-1 cells which do not express PXR (Fig. 6B). Cell growth inhibition did not

differ between control siRNA-treated and untransfected cells. In

examination of the effect on cell proliferation of combining,

anticancer drugs with pregnenolone or ketoconazole, pregnenolone

(moderately) and ketoconazole (more strongly) enhanced cell growth

inhibition in the presence of paclitaxel in SKOV-3 cells (Fig. 6C), but not in BG-1 cells (Fig. 6D). Cell growth inhibition in the

presence of paclitaxel for 48 and 72 h significantly differed

between pregnenolone- and ketoconazole-treated SKOV-3 cells.

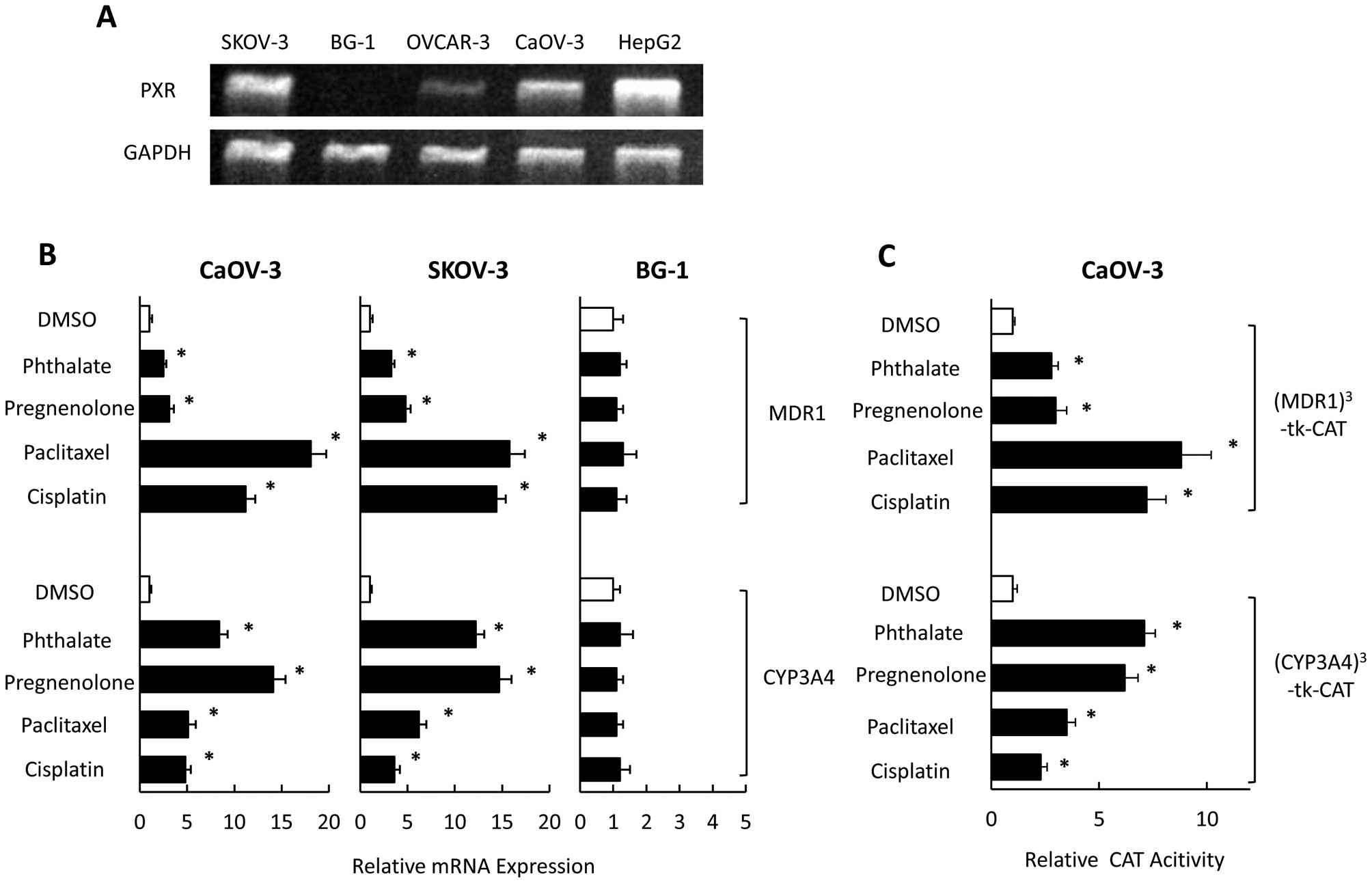

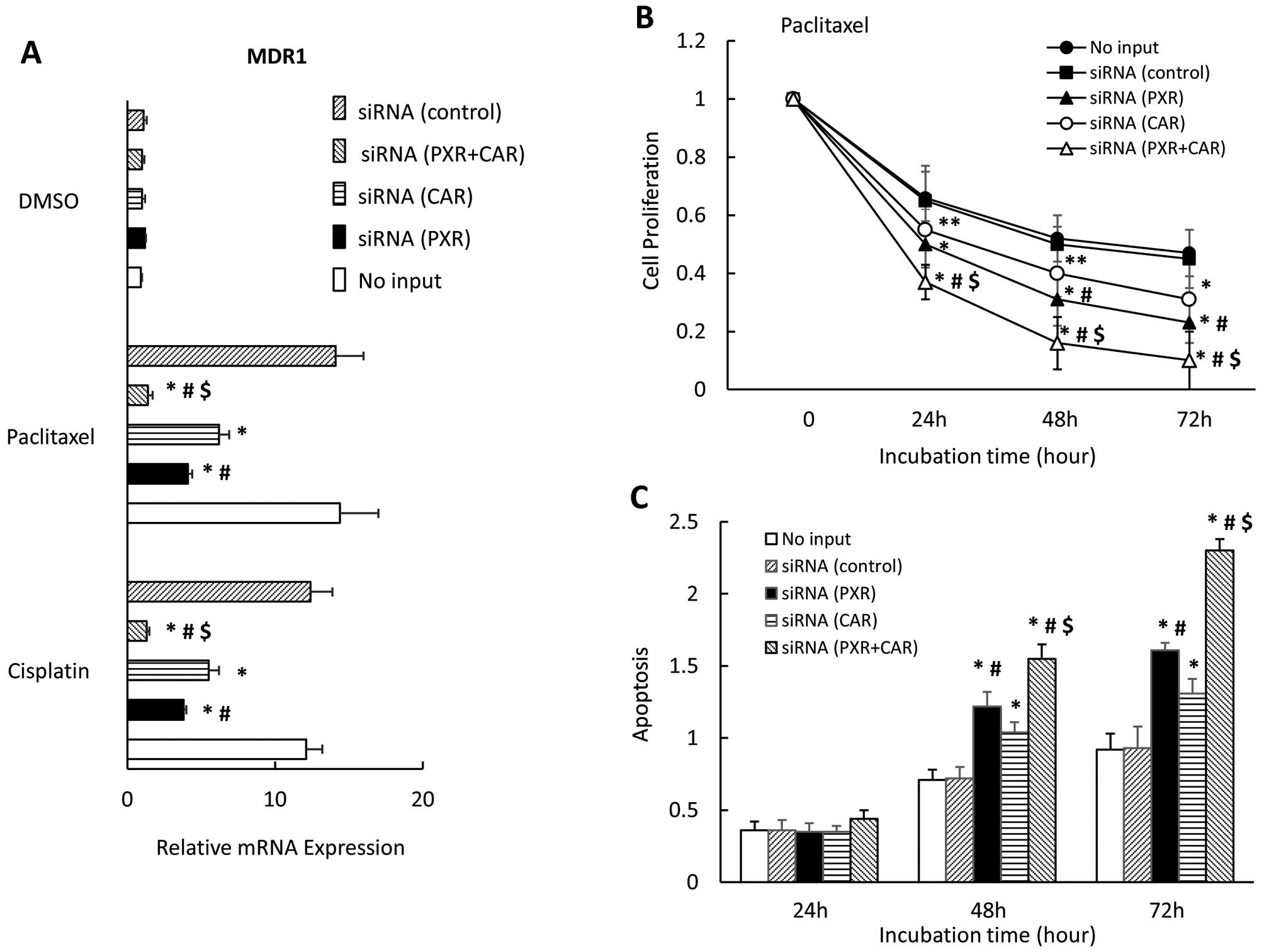

Effect of PXR and CAR siRNA on MDR1

expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis in CaOV-3 cells

Finally, we examined the effect of downregulating

PXR and CAR on MDR1 expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis

in the presence of paclitaxel in CaOV-3 cells. We observed that the

downregulation of both PXR and CAR expression completely blocked

the MDR1 expression enhanced by paclitaxel; PXR or CAR inhibited

MDR1 expression significantly but not completely (Fig. 7A). MDR1 expression significantly

differed between cells with downregulated PXR and those with

down-regulated CAR in the presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin. Use

of siRNA to interfere with both PXR and CAR significantly enhanced

cell growth inhibition in the presence of paclitaxel for 24, 48 and

72 h compared with that of either knocked-down PXR or CAR alone

(Fig. 7B). In the presence of

paclitaxel for 48 and 72 h, downregulating both PXR and CAR (i.e.,

in cells with both PXR and CAR siRNA transfections) significantly

enhanced apoptosis compared with cells transfected with either PXR

or CAR siRNA alone (Fig. 7C). Cell

growth inhibition and apoptosis significantly differed between

cells transfected with PXR siRNA and those transfected with CAR

siRNA in the presence of paclitaxel (Fig. 7C).

| Figure 7Effect of PXR- and CAR

siRNA on MDR1 expression, cell proliferation and apoptosis in

CaOV-3 cells. CaOV-3 cells were transfected with PXR, CAR or

control siRNA and treated with paclitaxel or DMSO for 36 h.

MDR1 mRNA expression was analyzed by quantitative real-time

PCR. Each experiment was performed in triplicate 4 times (internal

control, 18S; negative control, DMSO). Change in gene expression

was calculated as ratio of target gene to internal control (A).

CaOV-3 cells were transfected with PXR-, CAR- or control

siRNA or no siRNA, and were seeded and incubated with paclitaxel

for 0, 24, 48 or 72 h (B). TUNEL assay of apoptotic CaOV-3 cells

transfected with PXR-, CAR- or control siRNA, or no siRNA

and treated with paclitaxel for 36 h (C). Results show mean ± SD of

5 independent experiments (*P<0.01;

**P<0.05 vs. control siRNA group,

#P<0.01 vs. CAR siRNA, $P<0.01 vs. PXR

siRNA). |

Discussion

We investigated whether inhibition of the

PXR-mediated pathway could affect cytotoxicity of the anticancer

drugs, paclitaxel and/or cisplatin, in several ovarian cancer cell

lines including CaOV-3, SKOV-3, and BG-1 cells, to examine the

possible effect of PXR on augmentation of drug sensitivity and

overcoming drug resistance. We observed that phthalate and

pregnenolone had significant effects on the PXR-CYP3A4 pathway,

whereas the PXR-MDR1 pathway was significantly increased in the

presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin. We also observed that

downregulating PXR strongly inhibited the augmentation of MDR1

expression and PXR-mediated transcription by PXR ligands, and

significantly enhanced the cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in

the presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin. In addition, we found that

pregnenolone moderately and ketoconazole strongly suppressed the

augmented MDR1 expression and PXR-mediated transactivation by

paclitaxel or cisplatin, and enhanced cell-growth inhibition and

apoptosis in the presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin. Cell growth

inhibition and apoptosis were significantly enhanced in the cells

transfected with PXR siRNA compared with those transfected

with CAR siRNA in the presence of paclitaxel.

We previously demonstrated that PXR ligands enhance

PXR-mediated transcription in a ligand- and promoter-dependent

fashion, which in turn differentially regulate expression of

individual PXR targets, such as CYP3A4 and MDR1, in endometrial

cancer cells (29). We also

observed that steroids and endocrine-disrupting chemicals enhanced

CYP3A4 expression, whereas the anticancer agents, paclitaxel or

cisplatin had positive effects on MDR1 expression in endometrial

cancer cells (29). In this study,

we observed that pregnenolone and phthalate mainly enhanced the

CYP3A4 pathway, including mRNA expression and PXR-mediated

transcription, but paclitaxel and cisplatin had stronger effects on

the MDR1 pathway in ovarian cancer cells. This implies two

different ligands and promoters, which differentially regulate

expression of individual PXR targets, such as CYP3A4 and MDR1, in

ovarian cancer cell lines.

MDR1 was originally identified because its

overexpression in cultured cancer cells was associated with an

acquired cross-resistance to multiple anticancer drugs, and it has

been shown to be an ATP-dependent efflux pump of hydrophobic

anticancer drugs (7). Clinical

paclitaxel resistance is often associated with MDR1 overexpression;

in vitro paclitaxel resistance typically occurs with

overexpression of the MDR1 gene (6). However, several clinical trials have

attempted to alter P-glycoprotein activity and thus improve

clinical outcomes using verapamil and dexamethasone; most of these

studies showed no clear-cut success (9–11).

An earlier report showed that siRNA targeted to MDR1 could

sensitize paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells in vitro

(35), which suggests that siRNA

treatment may present a new approach for treating MDR1-mediated

drug resistance. Here, we showed that the mRNA levels of

CYP3A4 and MDR1 were strongly inhibited in cells

transfected with PXR siRNA, in the presence of PXR ligands,

pregnenolone, phthalate, paclitaxel, and cisplatin, compared with

cells treated with control siRNA and untransfected cells. In

addition, we observed no PXR ligand that enhanced PXR-mediated

transactivation through MDR1 and CYP3A4 promoters in

cells transfected with PXR siRNA. These data suggest that

the PXR-CYP3A4 and PXR-MDR1 pathways are blocked by downregulated

PXR in ovarian cancer cells. Next, we found that downregulating PXR

expression significantly enhanced cell-growth inhibition and

apoptosis in the presence of the anticancer agents, paclitaxel and

cisplatin, which indicates that downregulating PXR in ovarian

cancer might alter its response to anticancer agents.

Pregnenolone is an endogenous steroid hormone, known

as a ligand for PXR (36,37). It has a strong positive effect on

the CYP3A4 pathway, compared with its effect on MDR1. The

combination of cisplatin or paclitaxel with pregnenolone suppressed

the MDR1 expression induced by anticancer agents in a

dose-dependent manner. Because pregnenolone also suppressed

PXR-mediated transcription through the MDR1 promoter in the

presence of paclitaxel or cisplatin, this suppression mediated by

PXR, and the binding of pregnenolone to PXR might inhibit the

PXR-mediated activation by paclitaxel and cisplatin. Ketoconazole,

an antifungal drug, is reported to inhibit the PXR activation by

binding to PXR (38) and to be a

PXR antagonist, an inhibitor of both PXR-mediated drug metabolism

and the MDR1 pathway in HepG2 cells (39). In this study, we showed that

ketoconazole strongly inhibited augmentation of the MDR1 pathway by

paclitaxel or cisplatin in dose-dependent manner. These data imply

that pregnenolone partially suppressed the MDR1 pathway because

pregnenolone weakly enhanced the MDR1 pathway through PXR. In

contrast, ketoconazole strongly inhibited the MDR1 pathway because

ketoconazole had no positive effect on PXR-mediated genes. The

different inhibitory effects on the MDR1 pathway might have caused

the different effects of pregnenolone and ketoconazole on cell

growth inhibition and apoptosis in the presence of paclitaxel or

cisplatin.

In this study, we observed PXR downregulation to

suppress PXR-mediated transactivation through the MDR

promoter, but it did not completely inhibit the paclitaxel or

cisplatin-augmented MDR1 expression. Moreover, ketoconazole, a PXR

antagonist, could not completely block the paclitaxel or

cisplatin-enhanced MDR1 expression; and RNA interference of both

PXR and CAR completely abolished MDR1 overexpression

and enhanced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in the presence

of paclitaxel compared with interference of either PXR or CAR

alone, which further indicates that both PXR-and CAR-mediated

pathways affect drug resistance. We also observed that stronger

effect of PXR downregulation on cell growth inhibition and

apoptosis compared with CAR downregulation in the presence

of paclitaxel. PXR and CAR reportedly share several ligands

including paclitaxel and cisplatin, and several target genes

including MDR1 (21,22,29,30).

Moreover, activation of phase I drug metabolism enzymes (such as

CYP3A4) by PXR and/or CAR might affect the mechanism for drug

resistance (40). Thus, the roles

of xenobiotic receptors such as PXR and CAR in drug resistance for

anticancer agents warrant further study.

In conclusion, inhibition of PXR-mediated pathways

could augment sensitivity, or even overcome resistance, to

anticancer agents in the treatment of ovarian cancer, suggesting a

novel means for ovarian cancer patients, especially for those that

have resistance to anticancer agents.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a research grant

from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and

Technology of Japan (no. 25462558).

References

|

1

|

Rubin SC, Randall TC, Armstrong KA, Chi DS

and Hoskins WJ: Ten-year follow-up of ovarian cancer patients after

second-look laparotomy with negative findings. Obstet Gynecol.

93:21–24. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Armstrong DK: Relapsed ovarian cancer:

Challenges and management strategies for a chronic disease.

Oncologist. 7(Suppl 5): 20–28. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence. Guidance on the use of paclitaxel in the treatment of

ovarian cancer. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta55.

Accessed January 22, 2003

|

|

4

|

McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, Kucera

PR, Partridge EE, Look KY, Clarke-Pearson DL and Davidson M:

Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and

cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N

Engl J Med. 334:1–6. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, James K, Cassidy

J, Mangioni C, Simonsen E, Stuart G, Kaye S, Vergote I, Blom R, et

al: Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus

cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial

ovarian cancer: Three-year results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:699–708.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tsuruo T, Naito M, Tomida A, Fujita N,

Mashima T, Sakamoto H and Haga N: Molecular targeting therapy of

cancer: Drug resistance, apoptosis and survival signal. Cancer Sci.

94:15–21. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ambudkar SV, Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Sauna ZE

and Gottesman MM: P-glycoprotein: From genomics to mechanism.

Oncogene. 22:7468–7485. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ling V: Multidrug resistance: Molecular

mechanisms and clinical relevance. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

40(Suppl): S3–S8. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dalton WS, Crowley JJ, Salmon SS, Grogan

TM, Laufman LR, Weiss GR and Bonnet JD: A phase III randomized

study of oral verapamil as a chemosensitizer to reverse drug

resistance in patients with refractory myeloma. A Southwest

Oncology Group study. Cancer. 75:815–820. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sonneveld P, Suciu S, Weijermans P, Beksac

M, Neuwirtova R, Solbu G, Lokhorst H, van der Lelie J, Dohner H,

Gerhartz H, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment

of Cancer (EORTC); Leukaemia Cooperative Group (LCG); Dutch

Haemato-Oncology Cooperative Study Group (HOVON). Cyclosporin A

combined with vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone (VAD)

compared with VAD alone in patients with advanced refractory

multiple myeloma: An EORTC-HOVON randomized phase III study

(06914). Br J Haematol. 115:895–902. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Leonard GD, Fojo T and Bates SE: The role

of ABC transporters in clinical practice. Oncologist. 8:411–424.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger

JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM,

Zetterström RH, et al: An orphan nuclear receptor activated by

pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell.

92:73–82. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson

TM, Moore JT and Kliewer SA: The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR

is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and

cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest. 102:1016–1023. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bertilsson G, Heidrich J, Svensson K,

Asman M, Jendeberg L, Sydow-Bäckman M, Ohlsson R, Postlind H,

Blomquist P and Berkenstam A: Identification of a human nuclear

receptor defines a new signaling pathway for CYP3A induction. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:12208–12213. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang H, LeCulyse E, Liu L, Hu M, Matoney

L, Zhu W and Yan B: Rat pregnane X receptor: Molecular cloning,

tissue distribution, and xenobiotic regulation. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 368:14–22. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Blumberg B, Sabbagh W Jr, Juguilon H,

Bolado J Jr, van Meter CM, Ong ES and Evans RM: SXR, a novel

steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev.

12:3195–3205. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pascussi JM, Jounaidi Y, Drocourt L,

Domergue J, Balabaud C, Maurel P and Vilarem MJ: Evidence for the

presence of a functional pregnane X receptor response element in

the CYP3A7 promoter gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 260:377–381.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Schuetz EG, Brimer C and Schuetz JD:

Environmental xenobiotics and the antihormones cyproterone acetate

and spironolactone use the nuclear hormone pregnenolone X receptor

to activate the CYP3A23 hormone response element. Mol Pharmacol.

54:1113–1117. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

de Wildt SN, Kearns GL, Leeder JS and van

den Anker JN: Cytochrome P450 3A: Ontogeny and drug disposition.

Clin Pharmacokinet. 37:485–505. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ketter TA, Flockhart DA, Post RM, Denicoff

K, Pazzaglia PJ, Marangell LB, George MS and Callahan AM: The

emerging role of cytochrome P450 3A in psychopharmacology. J Clin

Psychopharmacol. 15:387–398. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Synold TW, Dussault I and Forman BM: The

orphan nuclear receptor SXR coordinately regulates drug metabolism

and efflux. Nat Med. 7:584–590. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Geick A, Eichelbaum M and Burk O: Nuclear

receptor response elements mediate induction of intestinal MDR1 by

rifampin. J Biol Chem. 276:14581–14587. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kliewer SA, Goodwin B and Willson TM: The

nuclear pregnane X receptor: A key regulator of xenobiotic

metabolism. Endocr Rev. 23:687–702. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hartley DP, Dai X, Yabut J, Chu X, Cheng

O, Zhang T, He YD, Roberts C, Ulrich R, Evers R, et al:

Identification of potential pharmacological and toxicological

targets differentiating structural analogs by a combination of

transcriptional profiling and promoter analysis in LS-180 and

Caco-2 adenocarcinoma cell lines. Pharmacogenet Genomics.

16:579–599. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Guzelian J, Barwick JL, Hunter L, Phang

TL, Quattrochi LC and Guzelian PS: Identification of genes

controlled by the pregnane X receptor by microarray analysis of

mRNAs from pregnenolone 16alpha-carbonitrile-treated rats. Toxicol

Sci. 94:379–387. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Masuyama H, Nakatsukasa H, Takamoto N and

Hiramatsu Y: Down-regulation of pregnane X receptor contributes to

cell growth inhibition and apoptosis by anticancer agents in

endometrial cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 72:1045–1053. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gupta D, Venkatesh M, Wang H, Kim S, Sinz

M, Goldberg GL, Whitney K, Longley C and Mani S: Expanding the

roles for pregnane X receptor in cancer: Proliferation and drug

resistance in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 14:5332–5340. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yue X, Akahira J, Utsunomiya H, Miki Y,

Takahashi N, Niikura H, Ito K, Sasano H, Okamura K and Yaegashi N:

Steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR) as a possible prognostic

marker in epithelial ovarian cancer. Pathol Int. 60:400–406. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Masuyama H, Suwaki N, Tateishi Y,

Nakatsukasa H, Segawa T and Hiramatsu Y: The pregnane X receptor

regulates gene expression in a ligand- and promoter-selective

fashion. Mol Endocrinol. 19:1170–1180. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang Y, Masuyama H, Nobumoto E, Zhang G

and Hiramatsu Y: The inhibition of constitutive androstane

receptor-mediated pathway enhances the effects of anticancer agents

in ovarian cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 90:356–366. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xie W and Evans RM: Orphan nuclear

receptors: The exotics of xenobiotics. J Biol Chem.

276:37739–37742. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Qatanani M and Moore DD: CAR, the

continuously advancing receptor, in drug metabolism and disease.

Curr Drug Metab. 6:329–339. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Petru E, Sevin BU, Perras J, Boike G,

Ramos R, Nguyen H and Averette HE: Comparative chemosensitivity

profiles in four human ovarian carcinoma cell lines measuring ATP

bioluminescence. Gynecol Oncol. 38:155–160. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Smith JA, Ngo H, Martin MC and Wolf JK: An

evaluation of cytotoxicity of the taxane and platinum agents

combination treatment in a panel of human ovarian carcinoma cell

lines. Gynecol Oncol. 98:141–145. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Duan Z, Brakora KA and Seiden MV:

Inhibition of ABCB1 (MDR1) and ABCB4 (MDR3) expression by small

interfering RNA and reversal of paclitaxel resistance in human

ovarian cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 3:833–838. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Masuyama H, Hiramatsu Y, Kunitomi M, Kudo

T and MacDonald PN: Endocrine disrupting chemicals, phthalic acid

and nonylphenol, activate Pregnane X receptor-mediated

transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 14:421–428. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Masuyama H, Hiramatsu Y, Mizutani Y,

Inoshita H and Kudo T: The expression of pregnane X receptor and

its target gene, cytochrome P450 3A1, in perinatal mouse. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 172:47–56. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang H, Huang H, Li H, Teotico DG, Sinz M,

Baker SD, Staudinger J, Kalpana G, Redinbo MR and Mani S: Activated

pregnenolone X-receptor is a target for ketoconazole and its

analogs. Clin Cancer Res. 13:2488–2495. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Huang H, Wang H, Sinz M, Zoeckler M,

Staudinger J, Redinbo MR, Teotico DG, Locker J, Kalpana GV and Mani

S: Inhibition of drug metabolism by blocking the activation of

nuclear receptors by ketoconazole. Oncogene. 26:258–268. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chen Y, Tang Y, Guo C, Wang J, Boral D and

Nie D: Nuclear receptors in the multidrug resistance through the

regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters.

Biochem Pharmacol. 83:1112–1126. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|