Introduction

Hypertension is a medical condition in which the

pressure of blood in the arteries is consistently elevated. Of

note, 15-20% of adults worldwide are affected by hypertension,

which is defined as having a systolic blood pressure of at least

140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mmHg

(1). Although high blood pressure

typically does not exhibit any symptoms, it can lead to severe

health issues, such as peripheral arterial disease, atrial

fibrillation, stroke, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, vision

loss and dementia (2). Hypertension

is a leading cause of premature mortality globally. High blood

pressure is divided into primary or essential hypertension and

secondary hypertension. Of note, 90-95% of cases are primary,

characterized by high blood pressure caused by non-specific

lifestyle and genetic factors (3).

Risk factors for primary hypertension include excessive salt

consumption, obesity, smoking, a lack of physical activity and

alcohol consumption. The remainder 5-10% of cases fall under

secondary hypertension, which is high blood pressure caused by a

specific identifiable factor, such as chronic kidney disease,

kidney artery narrowing, an endocrine disorder, or the use of birth

control pills (4).

Electrolytes are compounds that play a crucial role

in various bodily functions. They help maintain the balance of

fluids inside and outside cells, as well as contribute to muscle

contraction and heart function. The evaluation of electrolyte

levels has been a focus of research worldwide for a number of

years. Any imbalance in electrolytes can disrupt normal bodily

functions, leading to abnormal increases or decreases in levels

(5). Electrolyte imbalances are

often the primary indicator of numerous diseases and are prevalent

in both the general population and hospitalized patients. Previous

research has indicated that electrolyte disorders are linked to

higher rates of morbidity and mortality (6). Imbalances in electrolyte levels can

also contribute to the development of severe cardiovascular

conditions, such as hypertension. It is crucial to investigate

whether electrolyte imbalances are connected to specific risk

factors for chronic diseases that can be life-threatening (7). Understanding this association can help

in the management of these risk factors by regulating serum

electrolyte levels. This proactive approach may aid in the

prevention or delay in the onset of these diseases and their

associated complications, particularly in cases of

hypertension.

Clinical investigations of renal function, including

uric acid, urea and creatinine levels, are essential for

identifying renal dysfunction, diagnosing renal disease, monitoring

disease progression, and assessing response to treatment. The

relative risk of severe renal damage in patients with uncomplicated

essential hypertension is low compared to other cardiovascular

complications (8). However, due to

the high prevalence of hypertension in the general population, it

remains the second leading cause of end-stage renal disease, with

the risk being significantly higher in individuals of African

origin. Renal dysfunction is recognized as an independent risk

factor for morbidity and mortality in congestive heart failure. The

well-established association between heart failure and chronic

kidney disease is known as the cardiorenal syndrome (9). It has been shown that renal dysfunction

is independently associated with the development of heart failure

in hypertensive patients. Hypertension and renal impairment have a

bidirectional cause-and-effect association, with each being a

common cause of the other. Therefore, the early diagnosis of kidney

disease is crucial for effectively managing patients with

hypertension (10).

Vitamin D is a prohormone that is converted

metabolically to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

[1,25(OH)2D]. This hormone activates the vitamin D receptor, which

then regulates the transcription of genes responsible for various

biological responses (11). Vitamin

D is obtained through the diet and exposure to sunlight, and plays

a crucial role in regulating calcium levels in the body. It

influences the absorption and metabolism of calcium by influencing

voltage-dependent calcium channels and the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). This system controls

renin production, which in turn affects the secretion of

parathyroid hormone (12). Research

conducted in recent years has revealed a number of other biological

functions of vitamin D, including cell differentiation, cell growth

inhibition, immunomodulation and the regulation of hormonal systems

(7). Additionally, vitamin D has

been shown to improve endothelial function by increasing nitric

oxide production, preventing calcification, maintaining vascular

tone and reducing inflammation. Furthermore, the lack of vitamin D

has been linked to the development of non-skeletal conditions, such

as hypertension, kidney disease, and insulin resistance (13). Therefore, the present study was

performed to determine the mechanisms through which electrolyte

disturbances in hypertensive patients are associated with renal

function and vitamin D levels in a Nigerian hypertensive

population.

Subjects and methods

Study area

The present study was conducted at the Federal

Teaching Hospital Ido (FETHI), Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State. Ekiti State

is primarily a highland area located ~50 m above sea level, with

coordinates of 7˚40'N 5˚15'E. It is bordered to the north by Kwara

State for 61 km, to the northeast by Kogi State for 92 km, to the

south and southeast by Ondo State, and to the west by Osun State

for 84 km. Ekiti is the 31st largest state in terms of area and the

30th most populous, with an estimated population of almost 3.3

million as of 2016 in Nigeria (14).

Study design

The present study was a case-control study conducted

on hypertensive patients attending the clinic at the Federal

Teaching Hospital Ido (FETHI), Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria from

February, 2023 to August, 2023. Data collection was performed using

a semi-structured questionnaire that included items on demographic

characteristics such as age, sex, etc., and anthropometric

parameters, such as weight and height. Sample size was calculated

using the following formula: N=Z2pq/d2. The

study population consisted of 155 subjects, comprising 83

hypertensive subjects and 72 sex- and age-matched healthy

normotensive subjects as controls. Hypertensive subjects aged 18-60

years, with or without anti-hypertensive treatment, who provided

consent were included in the study. Pregnant women, nursing

mothers, individuals with other health conditions, those taking

vitamins or mineral supplements, and those who did not provide

consent were excluded from the study. The control subjects

(normotensive) were apparently healthy individuals who had no

history of high blood pressure and had no underlying health

condition.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for sample collection was obtained

from the Health Research Ethics Committee at the Federal Teaching

Hospital Ido (FETHI), Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State. Informed consent was

obtained from each subject who participated in the study prior to

sample collection. Additionally, the study was conducted in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample collection and analysis

A total of 5 ml of blood samples were collected from

each subject via venipuncture and dispensed into a plain bottle.

The sample was allowed to clot for 1 h, after which the serum was

separated by centrifugation at 16,087 x g for 5 min at room

temperature. The serum was then carefully withdrawn into a

pre-labeled tube and stored at -20˚C until analysis.

Blood pressure measurements

Blood pressure was measured using a mercury

sphygmomanometer (KENZ Model 605P, Suzuken Co., Ltd.). Participants

were allowed to sit and rest in a quiet area for at least 15 min

before the measurements were taken. Blood pressure was measured on

the right arm with the arm relaxed and supported on a table at a

45˚ angle to the trunk. A total of three measurements taken at

5-min intervals were averaged for diastolic blood pressure (DBP)

and systolic blood pressure (SBP). Variations of <5 mmHg were

permitted. Based on their average SBP and DBP values, the study

participants were divided into two groups (the hypertensive and

non-hypertensive groups).

Body mass index (BMI)

Weight measurements were performed using a weighing

scale, height was measured using a meter rule, and BMI was

calculated using the formula: Weight (kg)/height

(m2).

Biochemical parameters

Sodium and potassium levels were estimated using an

ion selective electrolyte (ISE) analyzer branded Biolyte 2000

(BioCare Corporation) (15).

Calcium, magnesium and phosphorus levels were estimated using

spectrophotometry (722G VIS Spectrophotometer, Shanghai Drawell

Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.) (16). Uric acid, creatinine and urea levels

were measured using a semi-auto chemistry analyzer (Mindray BA-88;

serial no. BH7AB2710, Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co.,

Ltd.) based on the enzyme colorimetry (Uricase TBHBA), Jaffe and

Berthelot methods, respectively (9).

Vitamin D was estimated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) techniques (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions and as previously described

(17).

Statistical analysis

The results are presented using tables and charts as

the mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis was conducted using

SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM Corp.). Statistical significance

was determined between groups using the Student's t-test, while

Pearson's correlation analysis was used to determine the

correlation between variables. A P-value <0.05 considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

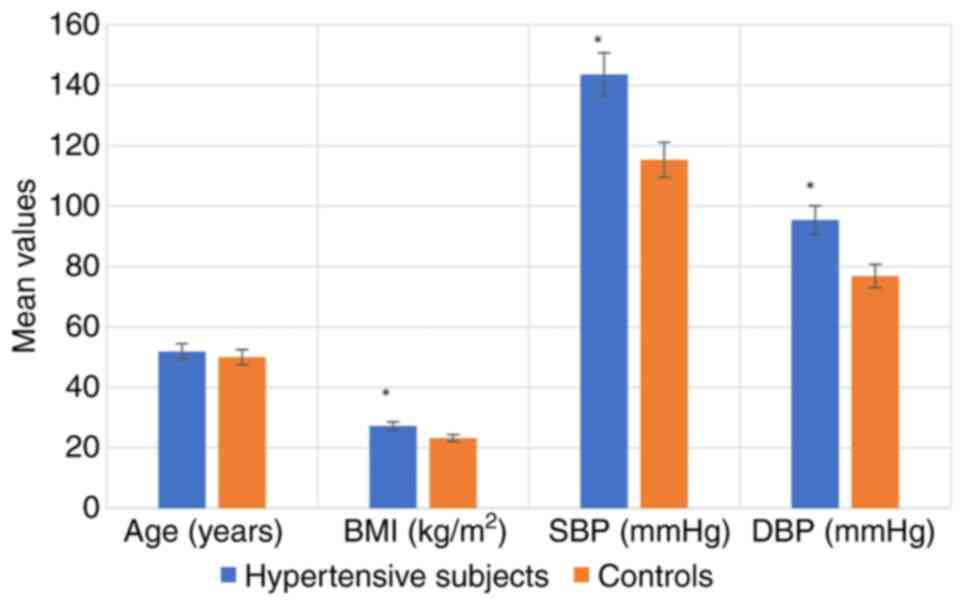

The anthropometric characteristics of the

hypertensive subjects and controls are illustrated in Fig. 1. The results indicated that BMI, SBP

and DBP were significantly higher in the hypertensive subjects

compared with the controls (P<0.05). The anthropometric

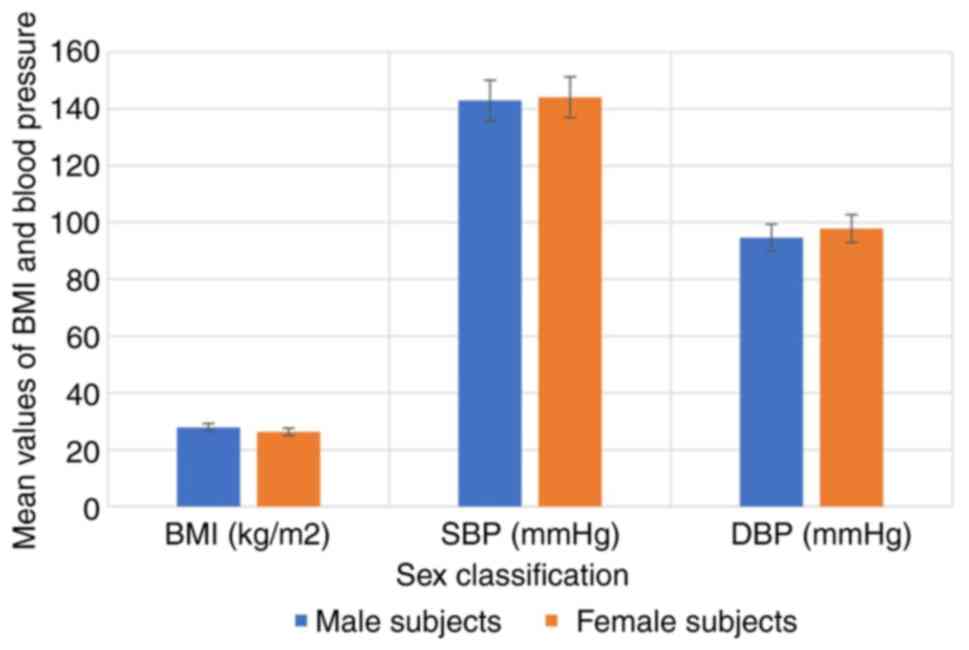

characteristics of the hypertensive subjects by sex are depicted in

Fig. 2, while the anthropometric

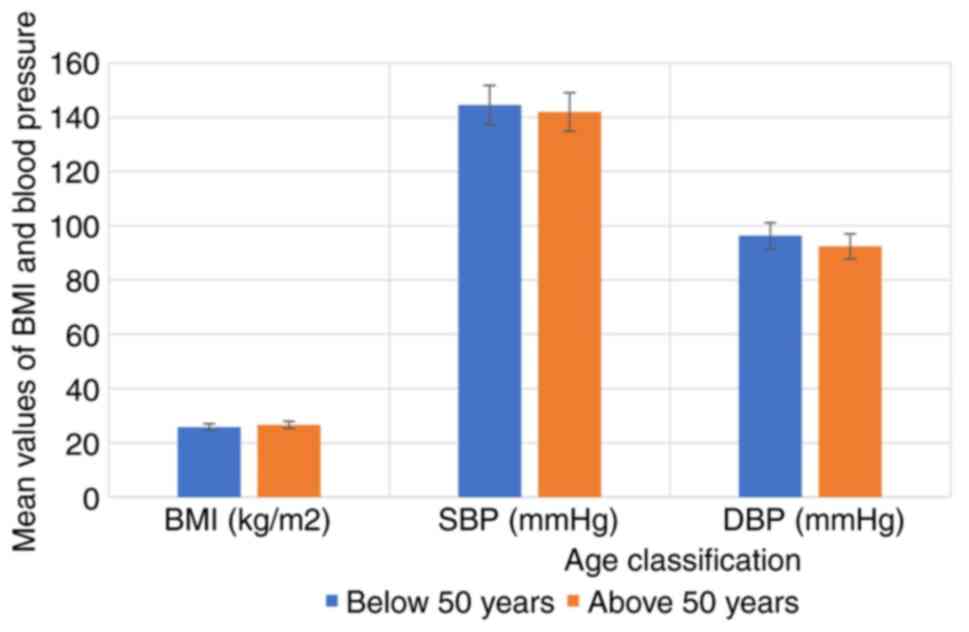

characteristics of the hypertensive subjects by age are depicted in

Fig. 3. The results revealed that

there were no significant differences in the BMI, SBP and DBP of

the hypertensive subjects as regards age and sex (P>0.05).

The renal function parameters, electrolyte and

vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects and the controls are

presented in Table I. The findings

revealed that the creatinine, urea, uric acid, magnesium, sodium,

sodium/potassium ratio and sodium/calcium levels were significantly

higher in the hypertensive subjects compared with the healthy

controls (P<0.05). The vitamin D, calcium, potassium and

phosphate levels were significantly lower in the hypertensive

subjects compared with the healthy controls (P<0.05). There was

no significant difference in the potassium/calcium ratio between

the two groups (P>0.05). The renal function parameters,

electrolyte and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects based

on sex are presented in Table II.

The results revealed that there were no significant differences in

all parameters studied based on sex (P>0.05). The renal function

parameters, electrolyte and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive

subjects according to age are demonstrated in Table III. The results indicated that

there were no significant differences in all parameters studied

based on age (P>0.05), apart from the phosphate levels, which

were significantly higher in the subjects <50 years of age

compared to those >50 years of age. The results of the

correlation analysis between renal function parameters, electrolyte

and vitamin D levels in the hypertensive subjects are presented in

Table IV and Fig. S1, Fig.

S2, Fig. S3, Fig. S4, Fig.

S5 and Fig. S6. The results

obtained revealed a significant correlation between the parameters

examined and blood pressure. Creatinine (r=0.211, P=0.142), urea

(r=0.088, P=0.543), uric acid (r=0.442, P=0.033), vitamin D

(r=0.281, P=0.048), sodium (r=0.176, P=0.221) and potassium

(r=0.342, P=0.020) exhibited positive correlations with SBP.

| Table IRenal function parameters,

electrolytes and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects and

controls. |

Table I

Renal function parameters,

electrolytes and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects and

controls.

| Parameter | Hypertensive

subjects (n=83) | Controls

(n=72) | P-value |

|---|

| Creatinine

(µmol/l) | 129.91±8.74 | 96.04±8.44 | 0.001a |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 6.87±1.06 | 4.81±0.89 | 0.006a |

| Uric acid

(µmol/l) | 329.84±64.42 | 294.30±55.74 | 0.039a |

| Magnesium

(mg/dl) | 1.19±0.29 | 0.97±0.28 | 0.044a |

| Phosphate

(mmol/l) | 1.12±0.51 | 1.66±0.62 | 0.001a |

| Sodium

(mmol/l) | 141.36±3.79 | 135.74±3.55 | 0.001a |

| Potassium

(mmoll) | 4.01±0.67 | 4.26±0.51 | 0.017a |

| Calcium

(mmol/l) | 2.12±0.31 | 2.47±0.33 | 0.012a |

| Vitamin D

(ng/ml) | 29.54±2.59 | 42.35±6.09 | 0.001a |

| Sodium/potassium

ratio | 35.25±2.26 | 31.86±2.35 | 0.001a |

| Sodium/calcium

ratio | 66.68±2.89 | 54.96±2.67 | 0.001a |

| Potassium/calcium

ratio | 1.89±0.16 | 1.72±0.34 | 0.179 |

| Table IIRenal function parameters,

electrolytes and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects as

regards sex. |

Table II

Renal function parameters,

electrolytes and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects as

regards sex.

| Parameter | Male subjects

(n=39) | Female subjects

(n=44) | P-value |

|---|

| Creatinine

(µmol/l) | 134.34±11.20 | 126.10±7.01 | 0.252 |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 5.25±1.52 | 5.83±1.67 | 0.213 |

| Uric acid

(µmol/l) | 301.25±70.66 | 284.50±72.50 | 0.514 |

| Magnesium

(mg/dl) | 1.02±0.24 | 1.15±0.31 | 0.215 |

| Phosphate

(mmol/l) | 0.98±0.49 | 1.26±0.49 | 0.069 |

| Sodium

(mmol/l) | 136.75±3.86 | 135.92±3.70 | 0.468 |

| Potassium

(mmol/l) | 4.13±0.79 | 4.07±0.53 | 0.802 |

| Calcium

(mmol/l) | 2.54±0.31 | 2.24±0.30 | 0.177 |

| Vitamin D

(ng/ml) | 30.04±15.26 | 27.70±15.05 | 0.111 |

| Sodium/potassium

ratio | 33.11±2.16 | 33.39±2.41 | 0.672 |

| Sodium/calcium

ratio | 53.84±3.91 | 60.68±3.84 | 0.098 |

| Potassium/calcium

ratio | 1.63±0.12 | 1.82±0.21 | 0.321 |

| Table IIIRenal function parameters,

electrolytes and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects as

regards age. |

Table III

Renal function parameters,

electrolytes and vitamin D levels of the hypertensive subjects as

regards age.

| Parameter | <50 years of age

(n=40) | >50 years of age

(n=43) | P-value |

|---|

| Creatinine

(µmol/l) | 134.49±15.03 | 124.02±11.24 | 0.053 |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 5.73±1.59 | 5.07±1.53 | 0.104 |

| Uric acid

(µmol/l) | 313.04±54.57 | 289.37±53.30 | 0.345 |

| Magnesium

(mg/dl) | 1.09±0.23 | 1.08±0.31 | 0.884 |

| Phosphate

(mmol/l) | 1.33±0.50 | 0.92±0.39 | 0.007a |

| Sodium

(mmol/l) | 136.52±3.58 | 136.35±3.85 | 0.886 |

| Potassium

(mmol/l) | 4.10±0.45 | 4.17±0.82 | 0.709 |

| Calcium

(mmol/l) | 2.39±0.33 | 2.53±0.24 | 0.167 |

| Vitamin D

(ng/ml) | 41.05±5.16 | 44.97±7.06 | 0.396 |

| Sodium/potassium

ratio | 33.29±3.01 | 32.69±2.97 | 0.459 |

| Sodium/calcium

ratio | 57.12±3.78 | 53.89±4.02 | 0.212 |

| Potassium/calcium

ratio | 1.72±0.15 | 1.65±0.16 | 0.623 |

| Table IVCorrelation between renal function

parameters, electrolytes and vitamin D levels in hypertensive

subjects. |

Table IV

Correlation between renal function

parameters, electrolytes and vitamin D levels in hypertensive

subjects.

| | | SBP | DBP | CRT | Urea | UA | Mg | Ca | Na | K | VitD |

|---|

| SBP | Pearson's

correlation | | 0.608b | 0.211 | 0.088 | 0.442 | -0.001 | -0.065 | 0.176 | 0.342 | 0.281a |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.543 | 0.033a | 0.996 | 0.655 | 0.221 | 0.020 | 0.048 |

| DBP | Pearson's

correlation | 0.608b | | 0.085 | 0.134 | 0.442 | 0.004 | -0.083 | -0.083 | 0.248 | -0.115 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.001 | | 0.558 | 0.353 | 0.033a | 0.981 | 0.568 | 0.566 | 0.082 | 0.425 |

| CRT | Pearson's

correlation | 0.211 | 0.085 | | 0.281a | 0.248 | -0.039 | -0.268 | -0.024 | 0.038 | -0.116 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.142 | 0.558 | | 0.048 | 0.082 | 0.787 | 0.060 | 0.870 | 0.791 | 0.421 |

| Urea | Pearson's

correlation | 0.088 | 0.134 | 0.281a | | 0.064 | -0.049 | -0.004 | -0.023 | 0.193 | -0.012 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.543 | 0.353 | 0.048 | | 0.661 | 0.734 | 0.980 | 0.873 | 0.179 | 0.936 |

| UA | Pearson's

correlation | 0.442 | 0.129 | 0.248 | 0.064 | | 0.038 | 0.108 | -0.023 | 0.306a | 0.122 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.033a | 0.371 | 0.082 | 0.661 | | 0.793 | 0.457 | 0.875 | 0.031 | 0.398 |

| Mg | Pearson's

correlation | -0.001 | 0.004 | -0.039 | -0.049 | 0.038 | | 0.292a | 0.269 | 0.095 | -0.108 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.996 | 0.981 | 0.787 | 0.734 | 0.793 | | 0.040 | 0.059 | 0.510 | 0.455 |

| Ca | Pearson's

correlation | -0.065 | -0.083 | -0.268 | -0.004 | 0.108 | 0.292a | | 0.116 | 0.330a | 0.124 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.655 | 0.568 | 0.060 | 0.980 | 0.457 | 0.040 | | 0.421 | 0.019 | 0.392 |

| Na | Pearson's

correlation | 0.176 | -0.083 | -0.024 | -0.023 | -0.023 | 0.269 | 0.116 | | 0.192 | -0.156 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.221 | 0.566 | 0.870 | 0.873 | 0.875 | 0.059 | 0.421 | | 0.182 | 0.279 |

| K | Pearson's

correlation | 0.342 | 0.248 | 0.038 | 0.193 | 0.306a | 0.095 | 0.330a | 0.192 | | 0.001 |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.020 | 0.082 | 0.791 | 0.179 | 0.031 | 0.510 | 0.019 | 0.182 | | 0.995 |

| Vit.D | Pearson's

correlation | 0.281a | 0.115 | -0.116 | -0.012 | 0.122 | -0.108 | 0.124 | -0.156 | 0.001 | |

| | Sig.

(2-tailed) | 0.048 | 0.425 | 0.421 | 0.936 | 0.398 | 0.455 | 0.392 | 0.279 | 0.995 | |

Discussion

Obesity is a well-known significant risk factor for

non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension. In the present

study, BMI was found to be slightly higher in the hypertensive

subjects compared to the control group. Previous systematic reviews

and retrospective studies have consistently indicated that higher

BMI values are associated with elevated blood pressure in adults

(18-19). The underlying mechanisms are

intricate and often interconnected. It has been reported that a BMI

≥23 serves as a risk factor for insulin resistance (20). Insulin resistance caused by the

accumulation of excessive lipids, leads to lipid deposition in

various tissues, such as blood vessels, triggering inflammation in

the area. At the same time, excess fat triggers the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, contributing to atherogenesis.

Ultimately, these factors disrupt blood pressure regulation,

potentially leading to elevated blood pressure or hypertension

(21). In the present study, SBP and

DBP were significantly higher in the hypertensive subjects compared

with the control group. These findings are consistent with the

findings of previous studies (22,23) that

also found elevated SBP and DBP in hypertensive individuals. The

increased pressure from hypertension can cause damage to blood

vessels and impair organ function, increasing the risk of heart

disease, stroke, chronic heart failure, kidney disease and other

related conditions (24).

Clinical investigations of renal function using

parameters such as uric acid, urea and creatinine are crucial for

identifying renal dysfunction, diagnosing renal disease, monitoring

disease progression and evaluating response to treatment. In the

present study, urea, creatinine and uric acid levels were

significantly higher in the hypertensive subjects compared with the

control group. This finding aligns with the findings of previous

studies (22,25-28).

The increase in the serum creatinine concentration may be

attributed to a decrease in creatinine clearance resulting from a

decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). This impairment

may be a consequence of prolonged hypertension or a contributing

factor to its development and progression (25). Furthermore, a reduction in renal

blood flow leads to a decrease in GFR, subsequently reducing the

distal tubular flow rate. This leads to increased urea reabsorption

and decreased secretion, potentially explaining the elevated serum

urea concentration (26). The

elevated serum uric acid levels observed in the present study

highlight its potential role in the pathophysiology of

hypertension. This aligns with recent literature suggesting that

hyperuricemia may contribute to hypertension through mechanisms

such as renal vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction

(27). Hyperuricemia can negatively

affect cardiovascular and renal function by reducing endothelial

nitric oxide levels and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the

macula densa of the kidney, thereby stimulating the RAAS (28). It may also trigger an inflammatory

response, potentially causing glomerular damage, tubular ischemia,

endothelial dysfunction, and the development of renal microvascular

disease by stimulating vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation,

ultimately leading to renal and systemic hypertension.

Hyperuricemia is also linked to the presence of target organ damage

in hypertensive patients (29).

In the present study, a significantly higher plasma

sodium level was found in the hypertensive subjects compared to the

controls. The reason for this difference may be attributed to

variances in the cell membrane, an increase in a sodium transport

inhibitor, a decreased sodium efflux rate constant and a reduction

in the activity of the ouabain-sensitive component of the

Na+-K+-ATPase pump (30). This finding supports the findings of

previous studies that have reported an association between

hypertension and elevated plasma sodium levels (30-32).

There are several mechanistic explanations for the link between

high sodium intake and blood pressure. These include enhanced

reabsorption and retention of filtered sodium through the renal

tubules, as well as activation of the brain RAAS. This system is

suggested to increase blood pressure through angiotensin II and

aldosterone, which promote local oxidative stress and activate the

sympathetic nervous system (31).

Furthermore, according to the ‘vasodysfunction theory’ of

salt-induced hypertension, salt loading leads to inadequate

decreases in systemic vascular resistance, resulting in increased

blood pressure (33). Salt

sensitivity, which varies among individuals, is considered to be a

key factor in this process. Therefore, treatments for essential

hypertension should focus on reducing plasma sodium levels by

decreasing dietary salt intake, increasing sodium excretion, or

inhibiting the RAAS (34).

The results of the present study revealed a

significant decrease in plasma potassium levels among hypertensive

subjects compared with the control group. This finding aligns with

the findings of previous studies that have reported lower plasma

potassium levels in both treated and untreated hypertensive

individuals compared to controls (5,35,36). The

most common cause of hypokalemia in hypertensive patients is the

use of diuretic drugs. Both thiazide and loop diuretics increase

urinary flow and sodium delivery through the collecting tubule,

leading to renal potassium secretion (36). This secretion is further increased in

the presence of diuretic-induced intravascular volume depletion and

secondary aldosterone stimulation (37). Since potassium is essential for

maintaining cardiac and vascular health, it is recommended to

provide hypertensive patients on diuretic medications with an

appropriate potassium supplement. This approach can improve

outcomes and help prevent the development of vascular

complications.

Magnesium plays a crucial role in regulating blood

pressure by controlling vascular tone and reactivity. It acts as a

calcium channel antagonist, which helps in the production of

vasodilator prostacyclins and nitric oxide. Furthermore, magnesium

helps maintain healthy endothelial function, regulates RAAS,

relaxes blood vessels and influences how blood vessels respond to

vasoactive agonists (38). In the

present study, magnesium levels were significantly higher in

hypertensive individuals compared to the controls. In vascular

smooth muscle cells, magnesium functions by inhibiting

transmembrane calcium transport and entry, thereby counteracting

the effects of calcium. When magnesium levels are low, there is an

increase in the intracellular free calcium concentration, leading

to vascular contraction. Magnesium deficiency can also lead to

endothelial dysfunction and increase in blood pressure, as the

ability of the body to relax blood vessels and regulates the RAAS

is impaired (39). On the other

hand, elevated plasma magnesium levels have been observed in cases

of both chronic and acute renal failure (40,41). The

slightly higher mean serum magnesium level in hypertensive patients

suggests a possible subclinical renal issue related to magnesium

excretion (42). It is important to

note that even though the mean magnesium level in these patients

was elevated, it still fell within the normal reference range. This

could explain why there were no obvious signs of renal dysfunction

in these patients.

In addition to the interdependent effect of sodium

and potassium, calcium and magnesium have also been implicated in

the regulation of blood pressure. In the present study, calcium

levels were found to be lower in the hypertensive subjects compared

with the controls; however, the difference was not statistically

significant. This finding is in agreement with the findings of

previous studies (43,44). Low calcium levels lead to an

increased activity of the parathyroid gland, which results in the

release of parathyroid hormone (PTH). This hormone can then lead to

the synthesis of calcitriol, either directly or mediated by PTH.

Calcitriol, in turn, increases intracellular calcium in vascular

smooth muscle cells causing vasoconstriction (43). The release of renin is stimulated by

low extracellular calcium and PTH, activating the RAAS. PTH also

enhances the synthesis of angiotensin II and aldosterone, further

promoting vasoconstriction, increasing renal water reabsorption,

and ultimately raising blood pressure (45). Therefore, increasing plasma calcium

levels through vitamin D supplements can reduce blood pressure in

hypertensive patients.

Vitamin D deficiency is an independent risk factor

for high blood pressure and is also associated with an increased

risk of cardiovascular mortality. The present study found that

vitamin D levels were significantly lower in hypertensive subjects

compared with the control group. Studies have suggested that

individuals with lower levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 may be more likely to

develop hypertension. This is due to the fact that a deficiency in

1,25(OH)2D3 can lead to the increased activity of the RAAS, both in

the body as a whole and specifically in the kidneys (46). In a low 1,25(OH)2D3 setting, there is

often an increase in the plasma renin concentration, which can

raise sympathetic activity and increase intra-glomerular pressure.

This can predispose individuals to hypertension, a decrease in the

glomerular filtration rate, and eventual cardiovascular damage

(47). Aside from the RAAS, vitamin

D can also influence hypertension through several other mechanisms.

Vitamin D plays a role in calcium homeostasis by promoting the

production of calcium transporters, increasing calcium reabsorption

in the kidneys, and stimulating the release of calcium from bones

by osteoclasts (48). Consequently,

a deficiency in vitamin D can lead to a decrease in plasma

Ca2+ levels, triggering the secretion of PTH from the

chief cells in the parathyroid gland to counteract this imbalance.

Numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that elevated

PTH levels are linked to a higher SBP and DBP, as well as an

increased prevalence of hypertension in general (47). Several studies have reported a direct

association between low plasma 25(OH)D concentrations and the risk

of developing hypertension and related complications (47,49,50).

Therefore, supplementation with vitamin D appears to be a promising

therapeutic option for these patients.

The results of the present study revealed a

significant correlation between renal function parameters,

electrolyte and vitamin D levels in hypertensive subjects.

Creatinine, urea, uric acid, vitamin D, sodium and potassium were

all found to be positively correlated with SBP. Previous research

has also shown a positive correlation between electrolytes,

particularly sodium and potassium, and SBP in hypertensive subjects

(18). Vitamin D deficiency has been

shown to be associated with an increased risk of developing

hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Low serum vitamin D

levels have been identified as a risk factor for cardiovascular

disease and are linked to a higher incidence of hypertension,

insulin resistance, obesity, metabolic syndrome, impaired fasting

blood glucose levels, and dyslipidemia (51,52).

Renal blood flow autoregulation may not completely protect the

kidneys from the effects of moderately elevated systolic blood

pressure. Early active management of moderate systolic hypertension

in all adults could potentially reduce the risk of developing

chronic kidney disease later in life. Maintaining healthy blood

pressure levels is essential for preserving kidney function.

One limitation of the present study was the

selection of participants from a specific region or hospital, which

may not be representative of the entire hypertensive Nigerian

population. Furthermore, the present study was a ‘snapshot’ of a

single point in time, and may not capture changes in electrolytes,

renal biomarkers and vitamin D levels over time during the course

of treatment. Despite these limitations, the present study has key

implications for clinical practice, such as identifying new targets

for treatment or improving existing treatments, as well as setting

a template for future research.

In conclusion, in the present study, electrolyte

imbalance, renal dysfunction and vitamin D deficiency were observed

in hypertensive subjects. The present study also revealed

significant correlations between parameters that may affect renal

function or be influenced by renal impairment. These findings

emphasize the importance of assessing and monitoring these

biochemical markers as they could improve prognosis, aid in early

diagnosis of kidney damage, and assist in determining the optimal

level of therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, the findings of

the present study support the use of vitamin D supplementation as

adjunctive therapy to manage hypertension, particularly in patients

with vitamin D deficiency. Understanding the association between

renal biomarkers, electrolytes imbalance and vitamin D levels may

contribute to reducing the risk of developing cardiovascular

disease and kidney damage, and may aid in the development of more

effective treatment strategies to improve blood pressure control.

However, further studies are required to focus on the analysis of

additional biomarkers and to investigate hypertensive groups with

different demographic characteristics. Furthermore, interventional

design studies are warranted to evaluate the effects of vitamin D

supplementation, electrolyte imbalance correction, and renal

biomarkers-guided therapy on blood pressure control and

cardiovascular health.

Supplementary Material

Scatter plot illustrating a

significant positive correlation between vitamin D and systolic

blood pressure.

Scatter plot illustrating a

significant positive correlation between uric acid concentration

and diastolic blood pressure.

Scatter plot illustrating a

significant positive correlation between the urea and creatinine

concentration.

Scatter plot illustrating a

significant positive correlation between the calcium and potassium

concentration.

Scatter plot illustrating a

significant positive correlation between the magnesium and calcium

concentration.

Scatter plot illustrating a

significant positive correlation between the potassium and uric

acid concentration.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AOO and BOO conceptualized the study. The

methodology was developed by AOO, EAO and OOO. Formal analyses and

visualization were conducted by OOO and OOE. Resources were

contributed by AOO, EAO, BOO, OOO and OOE. EAO wrote the original

draft of the manuscript, while review and editing were performed by

all the authors. Supervision was provided by AOO and BOO. EAO was

responsible for coordination with the co-authors and the submission

of the article. OOO and EAO confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval for the collection of samples was

obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee, Federal

Teaching Hospital Ido (FETHI), Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State

(ERC/2023/02//28/911B). Informed consent was obtained from each

subject who participated in the study before the collection of

samples. Furthermore, the study was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mills KT, Stefanescu A and He J: The

global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 16:223–237.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Princewel F, Cumber SN, Kimbi JA, Nkfusai

CN, Keka EI, Viyoff VZ, Beteck TE, Bede F, Tsoka-Gwegweni JM and

Akum EA: Prevalence and risk factors associated with hypertension

among adults in a rural setting: The case of Ombe, Cameroon. Pan

Afr Med J. 34(147)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA and Ezzati M:

Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for

elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol.

18:785–802. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Humphrey JD: Mechanisms of vascular

remodeling in hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 34:432–441.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wu D, Chen Y, Guan H and Sun Y:

Association of abnormal serum electrolyte levels with hypertension

in a population with high salt intake. Public Health Nutr.

22:1635–1645. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Iqbal S, Klammer N and Ekmekcioglu C: The

effect of electrolytes on blood pressure: A brief summary of

meta-analyses. Nutrients. 11(1362)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chiu HF, Venkatakrishnan K, Golovinskaia O

and Wang CK: Impact of micronutrients on hypertension: Evidence

from clinical trials with a special focus on meta-analysis.

Nutrients. 13(588)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ekun OA, Daniel F, Adebola P, Ajibare A,

Ekun OO, Omogoroye OO, Ilori OS, Oluwasayo BJ, Oshundun MF and

Oyegbami SR: Assessment of plasma sodium to potassium ratio, renal

function, markers of oxidative stress, inflammation, and

endothelial dysfunction in nigerian hypertensive patients. Int J

Hypertens. 7(6365947)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tamanji MT, Ngwakum DA and Mbouemboue OP:

A profile of renal function in Northern Cameroonians with essential

hypertension. Cardiorenal Med. 7:324–333. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

AbdAllah AA, Abdelrahman SF, Ahmed SA,

Abdalla AM, Dafalla AM and Modawe A: Assessment of serum urea,

creatinine and uric acid in sudanese hypertensive patients. Iraqi

Natl J Med. 3:33–42. 2021.

|

|

11

|

Zmijewski MA: Vitamin D and human health.

Int J Mol Sci. 20(145)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Morvaridzadeh M, Sepidarkish M, Fazelian

S, Rahimlou M, Omidi A, Ardehali SH, Sanoobar M and Heshmati J:

Effect of calcium and vitamin D Co-supplementation on blood

pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther.

42:e45–e63. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Khanolkar S, Hirani S, Mishra A, Vardhan

S, Hirani S, Prasad R and Wanjari M: Exploring the role of vitamin

D in atherosclerosis and its impact on cardiovascular events: A

comprehensive review. Cureus. 15(e42470)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

World Gazetteer. Largest cities and towns

statistics populations. Available at: https://citypopulation.de/en/nigeria/admin/NGA013_ekiti/,

2023.

|

|

15

|

Iyalomhe GB, Omogbai EK, Ozolua RI, Dada

FL and Iyalomhe OB: Electrolyte profiles in Nigerian patients with

essential hypertension. Afr J Biotechnol. 7:1404–1408. 2008.

|

|

16

|

Lindsay AL, Bazydlo MN and Neil SH:

Calcium, magnesium, and phosphate. Lab Med. 45:44–50. 2014.

|

|

17

|

He CS, Gleeson M and Fraser WD:

Measurement of circulating 25-Hydroxy vitamin D using three

commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits with comparison

to liquid chromatography: Tandem mass spectrometry method. ISRN

Nutr. 13(723139)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhang YX and Wang SR: High blood pressure

in Chinese youth across categories of BMI and waist circumference.

Blood Press Monit. 26:124–128. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Song L, Li J, Yu S, Cai Y, He H, Lun J,

Zheng L and Ye J: Body mass index is associated with blood pressure

and vital capacity in medical students. Lipids Health Dis.

22(174)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Okura T, Nakamura R, Fujioka Y,

Kawamoto-Kitao S, Ito Y, Matsumoto K, Shoji K, Sumi K, Matsuzawa K,

Izawa S, et al: Body mass index ≥ 23 is a risk factor for insulin

resistance and diabetes in Japanese people: A brief report. PLoS

One. 13(e0201052)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Nikbakht HR, Najafi F, Shakiba E, Darbandi

M, Navabi J and Pasdar Y: Triglyceride glucose-body mass index and

hypertension risk in Iranian adults: A population-based study. BMC

Endocr Disord. 23(156)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Oluboyo AO: Evaluation of selected renal

markers in hypertensive subjects in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Int J Med

Lab Res. 5:13–19. 2020.

|

|

23

|

Odewusi OO, Adigun HT, Omon EA, Obadire SO

and Egbebi HA: Assessment of oxidative stress and protein

modification in essential hypertensive subjects. Sokoto J Med Lab

Sci. 8:36–45. 2023.

|

|

24

|

Masenga SK and Kirabo A: Hypertensive

heart disease: Risk factors, complications and mechanisms. Front

Cardiovasc Med. 10(1205475)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gupta A and Khosla A: The impact of serum

biomarkers on the prognosis of hypertensive patients. J Hypertens.

39:1574–1582. 2021.

|

|

26

|

Emokpae AM and Abdu A: Serum uric acid

levels among Nigerians with essential hypertension. Niger J Physiol

Sci. 28:41–44. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Morris ST, McMurray JJ, Rodger RS and

Farmer R: Creatinine and urea clearance in hypertensive patients

with renal insufficiency. Kidney Int. 97:1032–1040. 2020.

|

|

28

|

Kumari R, Lal L, Jha B and Gadiya NK:

Evaluation of serum uric acid, urea, creatinine in hypertensive

patients. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 16:2304–2307. 2024.

|

|

29

|

Akpotaire PA and Seriki SA: Assessment and

correlation of serum urea and creatinine levels in normal,

hypertensive, and diabetic persons in Auchi, Nigeria. Arch Pathol

Clin Res. 7:7–16. 2023.

|

|

30

|

Grillo A, Salvi L, Coruzzi P, Salvi P and

Parati G: Sodium intake and hypertension. Nutrients.

11(1970)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Graudal N, Hubeck-Graudal T and Jurgens G:

A low dietary sodium dose is associated with a more pronounced

aldosterone response in normotensive than in hypertensive

individuals. Sci Rep. 13(19027)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Uchejeso OM, Lucy NL, Etukudoh NS, Etim II

and Dorathy SK: Sodium and potassium electrolytes levels among

hypertensive patients in Jos Metropolis. J Curr Emerg Med Rep.

1:1–5. 2021.

|

|

33

|

Morris RC, Schmidlin O, Sebastian A,

Tanaka M and Kurtz TW: Vasodysfunction that involves renal

vasodysfunction, not abnormally increased renal retention of

sodium, accounts for the initiation of salt-induced hypertension.

Circulation. 133:881–893. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Rust P and Ekmekcioglu C: Impact of salt

intake on the pathogenesis and treatment of hypertension. Adv Exp

Med Biol. 956:61–84. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Burnier M, Bakris G and Williams B:

Redefining diuretics use in hypertension: Why select a

thiazide-like diuretic? J Hypertens. 37:1574–1586. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Krogager ML, Søgaard P, Torp-Pedersen C,

Bøggild H, Gislason G and Kragholm K: Impact of plasma potassium

normalization on short-term mortality in patients with hypertension

and hyperkalemia. J Am Heart Assoc. 9(017087)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Do C, Vasquez PC and Soleimani M:

Metabolic alkalosis pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment: Core

curriculum. Am J Kidney Dis. 80:536–551. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sontia B and Touyz RM: Role of magnesium

in hypertension. Arch Biochem Biophys. 458:33–39. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Dominguez L, Veronese N and Barbagallo M:

Magnesium and hypertension in old age. Nutrients.

13(139)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ruiz MDC, Bermejo LC, Veronese N,

Fernández-Villalba E, Cuello AM, Kublickiene K, Raparelli V, Norris

CM, Kautzky-Willer A, Pilote L, et al: Magnesium in kidney function

and disease-implications for aging and sex-a narrative review.

Nutrients. 15(1710)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Azem R, Daou R, Bassil E, Anvari EM,

Taliercio JJ, Arrigain S, Schold JD, Vachharajani T, Nally J and Na

Khoul GN: Serum magnesium, mortality and disease progression in

chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 21(49)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sakaguchi Y: The emerging role of

magnesium in CKD. Clin Exp Nephrol. 26:379–384. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Villa-Etchegoyen C, Lombarte M, Matamoros

N, Belizán JM and Cormick G: Mechanisms involved in the

relationship between low calcium intake and high blood pressure.

Nutrients. 11(1112)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Hua Y, Liu H, Sun JY, Kong XQ, Sun W and

Xiong YQ: Association between serum calcium and the prevalence of

hypertension among US Adults. Front Cardiovasc Med.

8(719165)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zheng MH, Li FX, Xu F, Lin X, Wang Y, Xu

QS, Guo B and Yuan LQ: The interplay between the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and parathyroid hormone. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 11(539)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

McMullan CJ, Borgi L, Curhan GC, Fisher N

and Forman JP: The effect of vitamin D on renin-angiotensin system

activation and blood pressure: A randomized control trial. J

Hypertens. 35:822–829. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Jensen NS, Wehland M, Wise PM and Grimm D:

Latest knowledge on the role of vitamin D in hypertension. Int J

Mol Sci. 24(4679)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Rai V and Agrawal DK: Role of vitamin D in

cardiovascular diseases. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.

46:1039–1059. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Sheehy S, Palmer JR, Cozier Y, Bertrand KA

and Rosenberg L: Vitamin D and risk of hypertension among Black

women. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 25:168–174. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Mokhtari E, Hajhashemy Z and Saneei P:

Serum vitamin D levels in relation to hypertension and

pre-hypertension in adults: A systematic review and dose-response

meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Front Nutr.

9(829307)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Li YM, Guo LL, Zhou BJ and Cao RJ: Effect

of vitamin D level on vascular endothelial function and plasma

renin activity in patients with hypertension. J Chin Physician.

20:1665–1669. 2018.

|

|

52

|

Anagnostis P, Athyros VG, Adamidou F,

Florentin M and Karagiannis A: Vitamin D and cardiovascular

disease: A novel agent for reducing cardiovascular risk? Curr Vasc

Pharmacol. 8:720–730. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|