Introduction

Collision tumors refer to the occurrence of two

distinct tumors within the same organ or mass, each with separate

cellular lineages and genetic origins, but lacking a visible

transitional zone between them. This phenomenon is most commonly

observed in organs such as the liver, stomach, adrenal glands,

ovaries, lungs, kidneys and colon (1).

A collision tumor of the urinary bladder refers to a

very rare condition in which two distinct types of tumors occur

simultaneously within the same bladder. These tumors may have

different origins and growth patterns, and they may be benign or

malignant. The coexistence of two different tumor types in the same

location is what distinguishes a collision tumor from a composite

tumor, in which different cell types from the same tissues are

involved (2,3). The most common combination observed in

bladder cancer collisions is the concurrent presence of urothelial

carcinoma, which is the most common subtype of malignant bladder

tumors, and another type of tumor, such as adenocarcinoma, squamous

cell carcinoma (SCC) and other subtypes (4,5).

Urothelial carcinoma is the most common primary histological type

involving the urinary bladder, which comprises 90 to 95% of the

primary malignancies, while the other non-urothelial carcinomas,

e.g., adenocarcinoma, SCC, neuroendocrine carcinoma and lymphoma,

are uncommon and often diagnostically challenging (6,7). Both

adenocarcinoma and SCC account for 0.5-2% and 1-3% of the primary

bladder malignancies, respectively (8,9).

Oncogenic factors, such as p53, VEGF and EGFR, are known to play

critical roles in the signal transduction pathways of collision

tumors. Based on whether cancer cells can infiltrate the muscular

layer of the bladder, bladder cancer is divided into two subtypes,

namely non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscular

invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). The transurethral resection of

bladder tumor (TURBT) is the primary treatment modality for NMIBC

(10).

The present study reports and discusses a very rare

case of a bladder collision tumor. The references have been

inspected for reliability, and the report has been written

according to the CaReL guidelines (11,12).

Case report

Patient information

A 43-year-old female patient with a history of

vesical stones was referred to the Rzgary Oncology Clinic at Rzgary

Teaching Hospital (Erbil, Iraq) after being diagnosed with bladder

carcinoma.

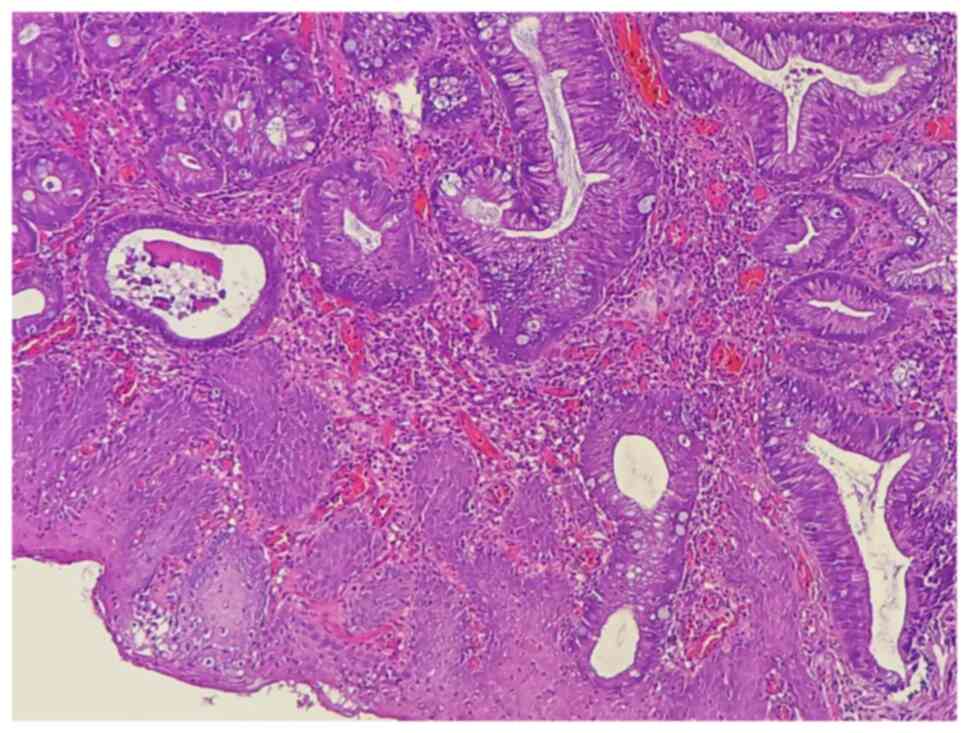

Clinical findings

The medical history of the patient included

controlled diabetes mellitus, hypertension and multiple sessions of

cystoscopic laser lithotripsy, as well as open vesical stone

extractions. She had previously undergone a cystoscopy-directed

TURBT to remove a mass from the urinary bladder, and a

histopathological examination of the biopsy (performed at Rzgary

Oncology Laboratory), identified the tumor as a moderately

differentiated T2 adenocarcinoma (Fig.

1). Following this, the patient was referred to the Smart

Health Tower (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq) for further management.

Diagnostic assessment

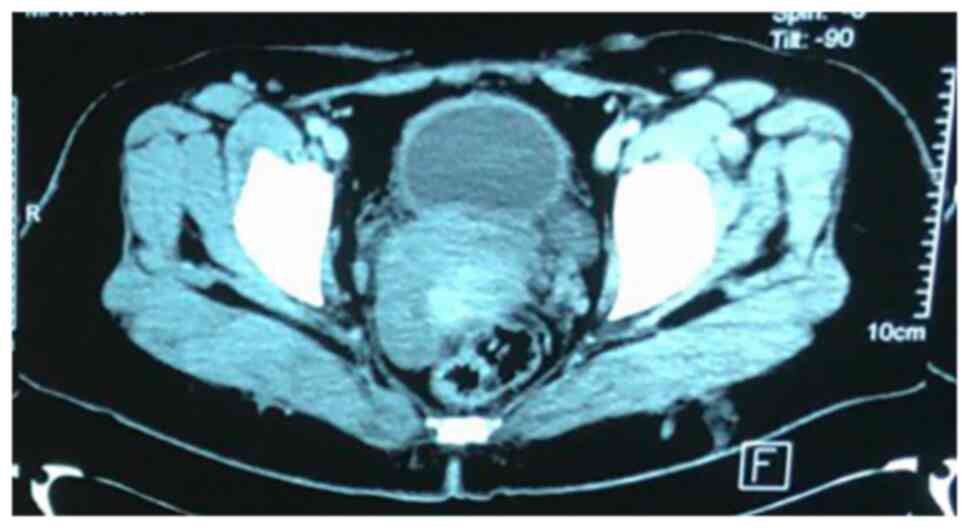

Initial diagnostic workup included an abdominal

ultrasound (U/S), which was followed by a contrast-enhanced

computed tomography (CT) scan as the previous surgery had been

based on the U/S alone. The CT scan was performed to provide a more

detailed assessment of the bladder wall and surrounding structures,

which revealed irregular, thickened bladder walls (8 mm), but no

gross mass lesion due to the previous TURBT procedure (Fig. 2). Given the history of adenocarcinoma

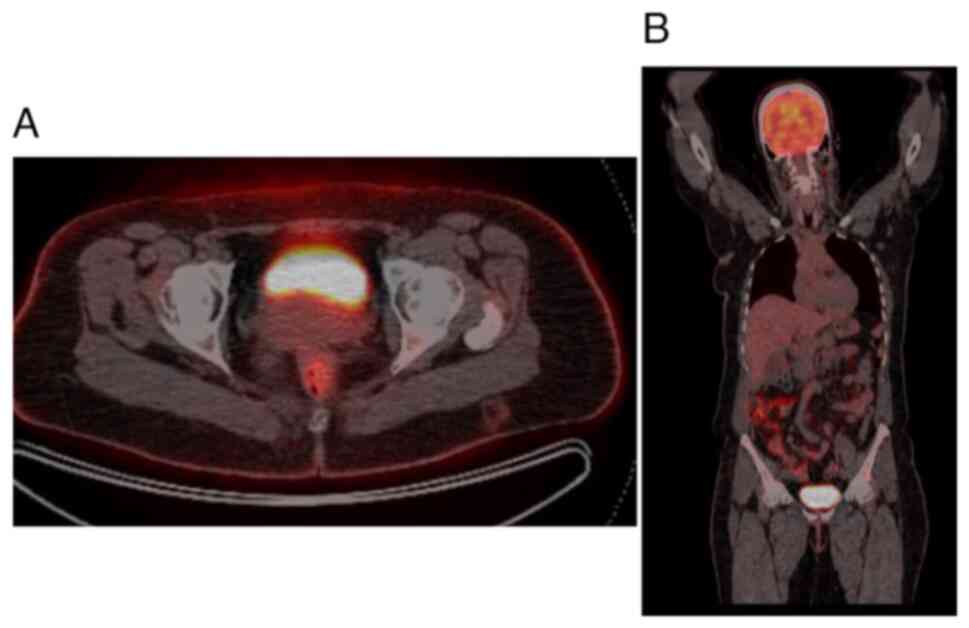

and to assess potential metastasis, a fluorodeoxyglucose positron

emission tomography (FDG-PET) was recommended by the

multidisciplinary team. The FDG-PET was crucial for detecting any

hypermetabolic nodular lesions suggestive of metastatic spread;

however, the results revealed no abnormal focal hypermetabolic

nodular lesions in the urinary bladder wall or elsewhere in the

body (Fig. 3). Based on the PET scan

findings and the initial TURBT biopsy, which revealed a T2-stage

adenocarcinoma, a radical cystectomy was advised for definitive

management.

Therapeutic intervention

The patient underwent radical cystectomy, during

which gross examination revealed a shrunken bladder (7x10 cm) with

a pale lesion at the trigone measuring approximately 25 mm. The

excised bladder specimen was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin

at room temperature for 24 h before being processed using the

DiaPath Donatello automated tissue processor. The tissue underwent

dehydration in a graded alcohol series, clearing in xylene and

paraffin infiltration, followed by embedding in paraffin wax using

the Sakura Tissue-Tek embedding center. Paraffin-embedded sections,

5-µm thick, were obtained using the Sakura Accu-Cut SRM microtome,

floated in a 40-50˚C water bath, and mounted on glass slides. The

slides were then baked at 60-70˚C overnight before staining with

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Bio Optica Co.) for 1-2 min at

room temperature using the DiaPath Giotto autostainer. The stained

slides were examined under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems

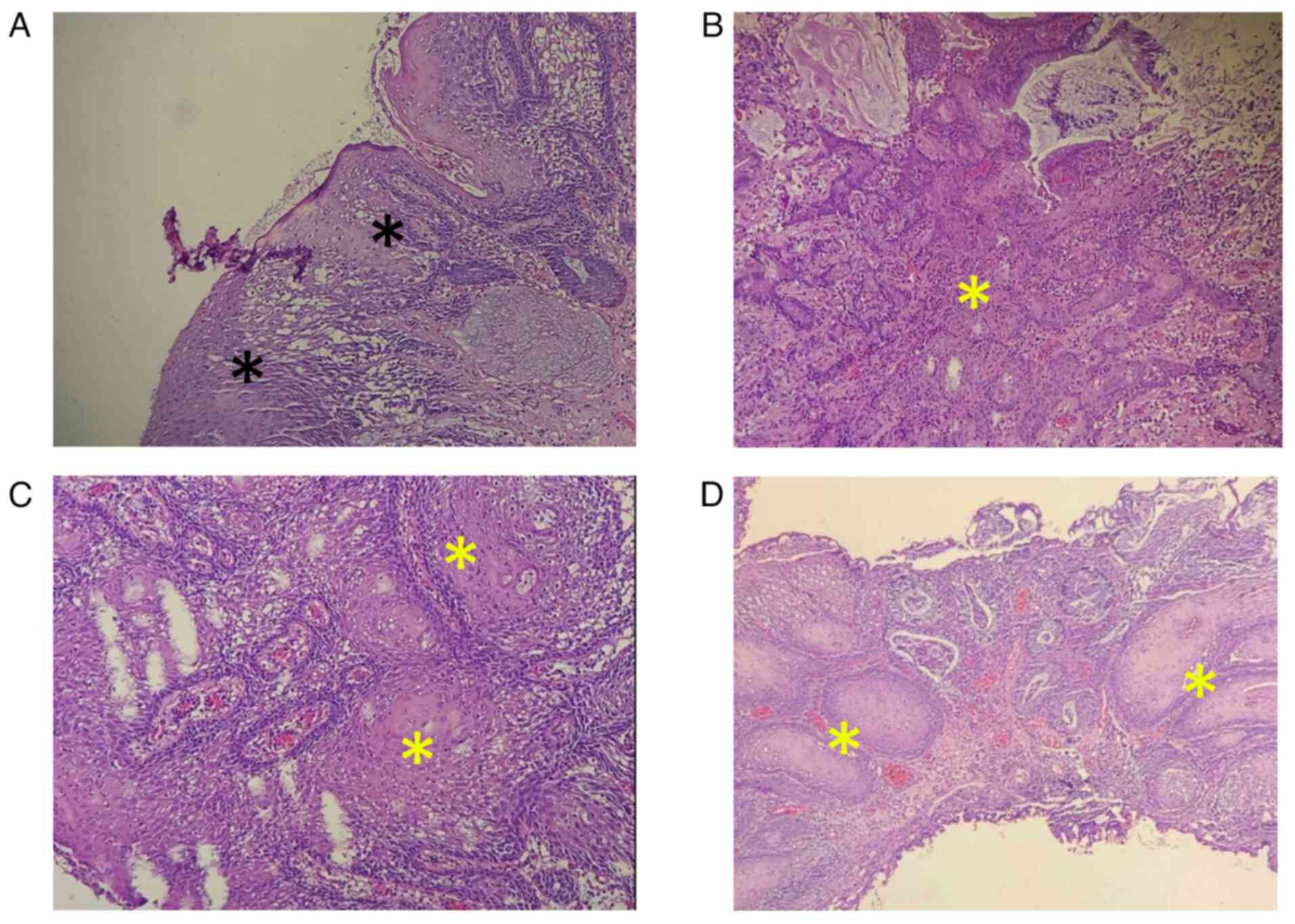

GmbH). A histopathological examination (HPE) revealed a marked

ulceration at the trigone with necrosis extending into the muscle

layer. Extensive squamous metaplasia throughout the bladder, SCC

in situ, and foci of superficially invasive SCC were

observed (Fig. 4). Glandular

metaplasia with dysplasia was also noted, extending into the distal

bladder, which exhibited significant inflammation and degenerative

changes. Additionally, two perivesical nodes were found to be free

of malignancy, and 18 lymph nodes were found after sectioning the

right and left pelvic nodes, and all were clear of malignancy. On

the TURBT, there was no residual adenocarcinoma. The final TNM

stage was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma pT2 N0 M0 and

well-differentiated SCC T1 N0 M0 as a collision tumor. This

combination of adenocarcinoma and SCC within the same mass is a

hallmark of collision tumors, underscoring the multifocal and

independent origins of each tumor type.

Follow-up

The patient is under an extensive follow-up regimen,

which includes regular urine cytology, liver function tests, and

monitoring of creatinine and electrolytes. Imaging studies of the

chest, urinary tract, abdomen and pelvis are also performed

periodically. Additionally, annual vitamin B12 monitoring is

conducted. No recurrence was observed after 1 year of

follow-up.

Discussion

While the case presented herein is unique in its

specifics, the literature review highlighted several cases of

urinary bladder collision tumors in patients aged 50 to 74 years,

with most cases involving male patients. Common symptoms included

hematuria, sometimes accompanied by urinary urgency, dysuria, or

the presence of blood clots. Diagnostic imaging techniques, such as

CT scans, ultrasounds and MRIs, have been frequently employed to

identify the tumors and assess their extent. Surgical interventions

were the primary treatment methods, including TURBT and radical

cystectomy, often combined with pelvic lymph node dissection. In

some instances, additional treatments such as chemotherapy or

immunotherapy were utilized to manage the disease. Patient outcomes

varied; while some patients experienced recurrence or metastasis,

leading to further complications or mortality, others had

successful surgeries and remained free from recurrence for several

months to years following treatment. The majority of cases (60%)

were found to result in either recurrence or mortality, while 2

cases exhibited no recurrence following an average follow-up period

of 6.5 months (2,10,13-15)

(Table I). By contrast, the patient

in the present study remained free from recurrence during

follow-up. It is noteworthy that, although the cases reviewed

predominantly involve male patients, the present case pertains to a

female patient, thereby contributing to the diversity in the

clinical presentation of bladder collision tumors.

| Table ISummary of several reported cases of

urinary bladder collision tumors in the literature. |

Table I

Summary of several reported cases of

urinary bladder collision tumors in the literature.

| | Imaging used for

diagnosis | | Tumor

characteristics | |

|---|

| Author(s) | Country, year of

publication | Age, years | Sex | Presentation | U/S | CT/MRI | Management | Location | Gross-section

size | HPE | Adjuvant

chemotherapy | Recurrence | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Gandhi et

al | India, 2017 | 73 | Male | Hematuria for15

days | Revealed a bladder

mass | Showed a bladder mass

measuring 5.6x2.4 cm with significant bilateral pelvic

lymphadenopathy | Radical

cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and

resection of a sigmoid colon serosal deposit | Posterior wall and

dome of the bladder | 6x4.5x3 cm | Large cell

neuroendocrine carcinoma with adenocarcinoma component | Recommended but

refused by the patient | Patient died 4 months

post-surgery | (2) |

| Jiang et

al | China, 2023 | 64 | Male | Urinary urgency,

frequent urination, dysuria, and recurrent hematuria. | Not applicable | Irregular and

abnormal signal shadow in the bladder, measuring 8.4x6 cm, and

abnormal signal in the central gland of the prostate, Chemo-therapy

(gemcitabine + cisplatin) and immunotherapy (tislelizumab) | Multiple TURBT

procedure+ Radical cystectomy with pelvic lymph node resection and

cutaneous ureterostomy in May 2021 | Bladder and prostate

involvement | Up to 8.4x6 cm | Collision tumor with

small cell small cell carcinoma (SCC) and high-grade urothelial

carcinoma | Recommended but the

patient had difficulty adhering to the treatment schedule due to

economic reasons | Neck and mediastinum

lymph nodes metastases; patient died of COVID-19 | (10) |

| Brinton et

al | United States,

1970 | 50 | Male | Gross, total,

painless hematuria for 4 days | Not applicable | Not applicable | TURBT followed by

total cystectomy and ileal loop urinary diversion. | Superior to the right

ureteral orifice | 2 cm (polypoid

tumor) | Carcinosarcoma of the

bladder with muscle invasion | Not applicable | No recurrence;

patient alive and well 5 months postsurgery. | (13) |

| Chen et

al | China, 2022 | 74 | Male | Gross hematuria for 3

months worsening in the past week, occasionally accompanied by

blood clots. | Revealed a substan

tial mass in the bladder measuring 3.1x 2.4x2.1 cm with a rich

blood flow signal. Additionally, the prostate was enlarged with

intense light spots | CT scan: Indicated

focal thickening of the left posterior wall of the bladder with a

cauliflower-shaped soft-tissue density shadow protruding into the

bladder. On contrast-enhanced CT, the lesion was mildly to

moderately enhanced, suggestive of a space-occupying lesion

consistent with bladder cancer | TURBT followed by

total cystectomy | Left posterior wall

of the bladder, 1 cm lateral to the left ureteral opening | A volume of mass was

3.0x2.0x 2.0 cm | Collision tumor

between primary malignant melanoma and high-grade non-invasive

urothelial papillary carcinoma. | No chemotherapy,

immunotherapy, or gene therapy was administered. | Patient died of

systemic metastasis 31 months after surgery | (14) |

| Kitazawa et

al | Japan, 1985 | 67 | Male | Occasional small

amounts of gross hematuria and dysuria, with discharge of a

fingertip-sized mass. | Not applicable | Not applicable | TURBT, section by

section. | Right posterior wall

of the bladder | 2.1x1.8 cm; the

specimen weighed 4.0 grams. | Giant cell tumor

associated with transitional cell carcinoma. | Not applicable | No recurrence or

metastasis 8 months after TURBT. | (15) |

Collision tumors may exhibit diverse origins and

growth patterns, often involving two distinct tumor types that

originate independently within the same mass. This combination of

adenocarcinoma and SCC in the present study within the same mass is

a hallmark of collision tumors, underscoring the multifocal and

independent origins of each tumor type (2). In contrast to collision tumors,

composite tumors involve different cell types from the same

tissues. The most frequently observed combination in bladder

collision tumors, as in the present case, is the simultaneous

presence of urothelial carcinoma and another type of tumor, such as

adenocarcinoma, or SCC (3).

Adenocarcinoma of the bladder emerges from the glandular cells of

the bladder. Unlike the more prevalent transitional cell carcinoma

type, it is less common. It can be in different areas of the

bladder, such as the mucosal layer and deeper muscle layers

(16). Cigarette smoking increases

the risk of bladder cancer, as harmful chemicals in tobacco smoke

are absorbed into the bloodstream and excreted through the kidneys,

exposing the bladder lining to carcinogens. Bladder cancer is more

common in older adults, especially men. Occupational exposures to

chemicals such as aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons, found in industries such as rubber, dye, and chemical

production also increase the risk. Prolonged exposure to chemicals

in textiles, paints, and plastics, along with chronic urinary

infections, can further increase this risk. Additionally, radiation

therapy, certain diabetes medications, and chronic Schistosoma

haematobium infection are linked to higher bladder cancer risk

(17,18). The starting point of the disease is a

genetic mutation, which can lead to uncontrolled cell growth and

division. These mutations can be inherited or occur spontaneously

during a person's lifetime; chronic inflammation and long-term

inflammation in an organ can create an environment that promotes

the growth of cancer cells (19).

The signs and symptoms of bladder collision tumors can vary. The

urine may appear pink, red, or dark brown, and the presence of

blood can be intermittent or consistent; also, there may be painful

urination, urinary urgency, and pelvic pain (4). In the present study, the patient was

diagnosed with bladder carcinoma and was referred to the Rzgary

Oncology Clinic.

The diagnosis of bladder carcinoma often involves

various tests, such as urine analysis, imaging studies, and

cystoscopy. A biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis

(12). Since this type of cancer is

mostly diagnosed in the advanced stages and is associated with high

recurrence rates, the understanding of gene expression regulation

is significant for early diagnosis and treatment. Epigenetic

modifications, which alter gene expression without changing the DNA

sequence, have been extensively studied as flexible and important

therapeutic targets for cancer treatments. Mutations in genes such

as FGFR3, PIK3CA, KDM6A and TP53 are common in bladder cancers and

disrupt normal gene regulation and cell growth, leading to

uncontrolled cell growth and tumor formation (20). The case described herein underwent a

CT scan with IV contrast followed by a PET scan. The HPE of the

specimen confirmed the diagnosis.

The management of bladder collision tumors includes

cancer staging and grading, the assessment of the overall health of

the patient and the consideration of the preferences of the

patient. A general outline of the management options for collision

bladder is TURBT, which is the standard initial treatment for

non-invasive or early-stage bladder cancer, radical cystectomy,

intravesical therapy and radiation therapy. Chemotherapy and

immunotherapies are used in the advanced stages. Some bladder

cancers with specific molecular features may be treated with

targeted therapies that aim to inhibit specific abnormal proteins

or pathways involved in cancer growth (21,22).

This case undergone radical cystectomy as far as it was a localized

early-stage disease.

Early detection and appropriate treatment are

crucial for better outcomes in bladder carcinoma. Regular check-ups

and prompt medical attention for concerning symptoms can improve

prognosis and increase the likelihood of successful treatment. As

with any type of cancer, a multidisciplinary approach involving

urologists, oncologists and other healthcare specialists is often

necessary to provide comprehensive care to individuals affected by

bladder carcinoma (5). Although it

is a rare disease, regular follow-up is necessary in cases of

bladder cancer (13-16,23).

The case in the present study was kept on an extensive and regular

follow-up schedule by conducting urine cytology, liver function

tests, serum creatinine and electrolytes.

In conclusion, collision tumor of the bladder is a

rare disease; extensive radiological study and careful examination

of the biopsy are necessary to diagnose the condition.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SSO and SSF were the major contributors to the

conception of the study, as well as in the literature search for

related studies. HOA, FHK and BAA were involved in the literature

review, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the analysis and

interpretation of the patient's data. AMA, BOM, AAQ, SHK and JIH

were involved in the literature review, in the design of the study,

in revision of the manuscript and in the processing of the figures.

RMA was the pathologist who performed the histopathology diagnosis.

SHT was the radiologist who performed the assessed the case. SSO

and FHK confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The patient provided written informed consent to

participate and publish any related data in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent to

participate and publish any related data in the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Abdullah AM, Qaradakhy AJ, Ali RM, Ali RM,

Mahmood YM, Omar SS, Nasralla HA, Muhialdeen AS, Saeed YA, Dhair HM

and Mohammed RO: Thyroid collision tumors: A systematic review.

Barw Medical J. 2:44–56. 2024.

|

|

2

|

Gandhi JS, Pasricha S and Gupta G:

Collision tumor of the urinary bladder comprising large cell

neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Asian J Oncol.

3:144–146. 2008.

|

|

3

|

Miyazaki J and Nishiyama H: Epidemiology

of urothelial carcinoma. Int J Urol. 24:730–734. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Radović N, Turner R and Bacalja J: Primary

‘pure’ large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder:

A case report and review of the literature. Clin Genitourin Cancer.

13:375–e377. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rouanne M, Loriot Y, Lebret T and Soria

JC: Novel therapeutic targets in advanced urothelial carcinoma.

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 98:106–115. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ploeg M, Aben KK, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa

CA, Schoenberg MP, Witjes JA and Kiemeney LA: Clinical epidemiology

of nonurothelial bladder cancer: Analysis of the Netherlands Cancer

Registry. J Urol. 183:915–920. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tavora F and Epstein JI: Bladder cancer,

pathological classification and staging. BJU Int. 102:1216–1220.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, Garcia-Donas

J, Huddart R, Burgess E, Fleming M, Rezazadeh A, Mellado B,

Varlamov S, et al: Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic

urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 381:338–348. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Catto JW, Yates DR, Rehman I, Azzouzi AR,

Patterson J, Sibony M, Cussenot O and Hamdy FC: Behavior of

urothelial carcinoma with respect to anatomical location. J Urol.

177(1715)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jiang W, Pan C, Guo W, Xu Z, Ni Q and Ruan

Y: Pathologic collision of urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma

with small cell carcinoma: A case report. Diagnostic Pathology.

18(80)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, Kakamad FH, Ahmed

JO, Baba HO, Hassan MN, Bapir R, Rahim HM, Omar DA, Kakamad SH, et

al: Predatory Publishing Lists: A Review on the Ongoing Battle

Against Fraudulent Actions. Barw Med J. 2:26–30. 2024.

|

|

12

|

Prasad S, Nassar M, Azzam AY,

García-Muro-San José F, Jamee M, Sliman RKA, Evola G, Mustafa AM,

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, et al: CaReL guidelines: A consensus-based

guideline on case reports and literature review (CaReL). Barw Med

J. 2:13–19. 2024.

|

|

13

|

Brinton JA, Ito Y and Olsen BS:

Carcinosarcoma of the urinary bladder. A case report and review of

the literature. Cancer. 25:1183–1186. 1970.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Chen X, Ge H, Yang J, Huang B and Liu H:

Primary malignant melanoma of the bladder collides with high grade

non invasive urothelial papillary carcinoma: A case report. Oncol

Lett. 24:1–5. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kitazawa M, Kobayashi H, Ohnishi Y, Kimura

K, Sakurai S and Sekine S: Giant cell tumor of the bladder

associated with transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 133:472–475.

1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Dadhania V, Czerniak B and Guo CC:

Adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder. Am J Clin Exp Urol.

3(51)2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Taguchi S, Akamatsu N, Nakagawa T, Gonoi

W, Kanatani A, Miyazaki H, Fujimura T, Fukuhara H, Kume H and Homma

Y: Sarcopenia evaluated using the skeletal muscle index is a

significant prognostic factor for metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Clin Genitourin Cancer. 14:237–243. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ku JH, Byun SS, Jeong H, Kwak C, Kim HH

and Lee SE: Lymphovascular invasion as a prognostic factor in the

upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 49:2665–2680. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Roy S and Parwani :

AVA8/arpa.2009-0713-RS adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder. Arch

Pathol Lab Med. 135:1601–1605. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lee KH and Song CG: Epigenetic regulation

in bladder cancer: Development of new prognostic targets and

therapeutic implications. Translational Cancer Res. 30

(Suppl):677–688. 2017.

|

|

21

|

Crabb SJ and Douglas J: The latest

treatment options for bladder cancer. Br Med Bull. 128:85–95.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Witjes JA: Bladder carcinoma in situ in

2003: State of the Art. Eur Urol. 45:142–146. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Mingomataj E, Krasniqi M, Dedushi K,

Sergeevich KA, Kust D and Qadir AA: Cancer Publications in one year

(2023): A cross-sectional study. Barw Med J. 2(3)2024.

|