Introduction

SFTs, which are known to be either localized fibrous

tumors or fibrous mesotheliomas, are rare spindle-cell neoplasms

first reported as originating in the pleura (1). Although most reported SFTs tend to

originate within the thoracic cavity, extrathoracic SFTs, which

occur in a wide range of anatomic sites, have also been reported

(2). Recent immunohistochemical and

ultrastructural studies support the mesenchymal histogenesis of SFT

(3). Most SFTs in deep soft tissue

are indolent and are found incidentally in the course of

examinations for other disorders or during medical check-ups. Some

cases are also diagnosed with hypoglycemia, due to insulin-like

growth factor II (IGF-2) secreted by the tumor cells of SFT

(4). In the present case, SFT was

found in the pelvis, with urinary retention caused by tumor

pressure on the urethra.

SFT with high cellularity, pleomorphism and

increased mitotic activity is classified as malignant SFT. However,

infiltrative features that prevent total resection significantly

affect their outcome. The outcome for patients with extrapleural

SFTs is unpredictable based on histological assessment (5). Therefore, complete resection is

essential to prolong prognosis. However, surgical resection of a

large tumor in the pelvis often injures the pelvic nerve plexus and

damages urinary and erectile functions. In this study, we attempted

complete surgical resection while preserving urinary and erectile

functions.

Case report

A 41-year-old man was referred to our hospital with

urinary retention. Abdominal ultrasound sonography (US) and

computed tomography (CT) revealed a hypervascular mass lesion,

measuring 125×95×129 mm, in the pelvis (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

showed a mass with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and a

high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, as well as

mass-oppressed bladder, prostate and rectum in the retroperitoneum.

Blood biochemistry and urine examination results were in the normal

ranges, including prostate-specific antigen (PSA), α-fetoprotein

(AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9

(CA19-9). Transrectal biopsy showed SFT.

Following the diagnosis of SFT, a surgical resection

was performed using a retroperitoneal approach to prevent

peritoneal defects. During surgery, we performed an abruption

between the bladder and the peritoneum, entered the

retroperitoneum, and confirmed that the tumor was not connected to

neighboring organs such as the bladder, prostate, seminal vesicle

or rectum. A complete resection was performed, while preserving the

neural network related to urinary and erectile function, such as

the bladder branch of the pelvic nerve plexus and neurovascular

bundles (NVB). Macroscopically, the resected tumor was well

circumscribed and encapsulated, measuring 120×92×115 mm and

weighing 2,200 gr. The cut surface was grayish-white, showing

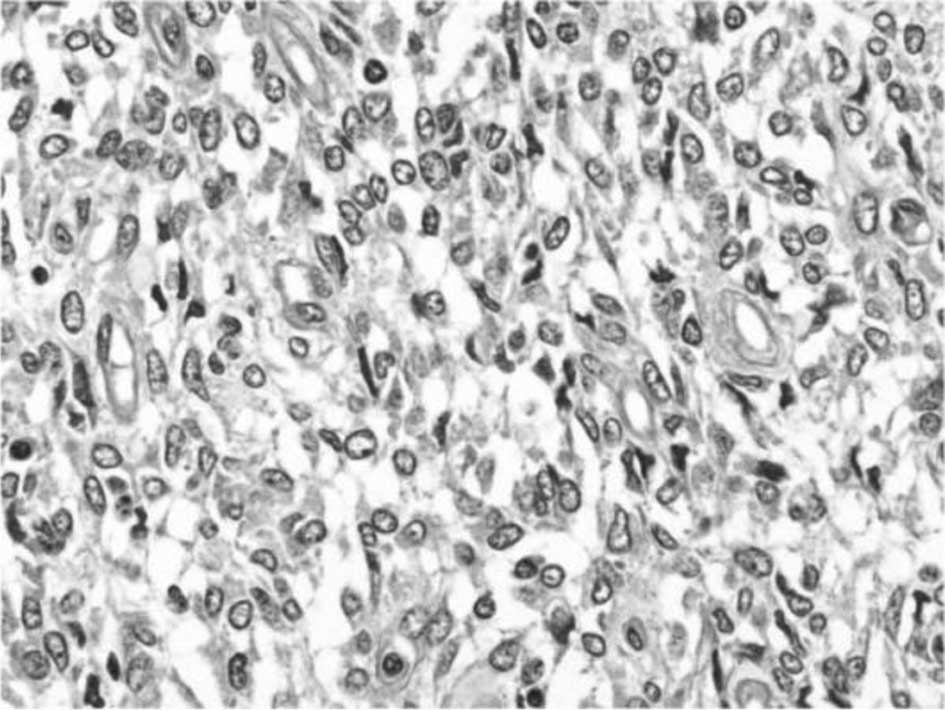

components of hemorrhaging. Microscopically, the tumor was composed

of spindle-shaped and oval cells in sarcoma, based on moderate

mitotic rate and cellularity (Fig.

2). Immunohistochemically, the tumor was positive for CD34,

CD99, vimentin, bcl-2 and p53, but was negative for keratin,

α-smooth muscle actin and S100 protein. The MIB-1 index, which

indicates cell proliferation capability, was 5%. Based on these

findings, the tumor was diagnosed to be malignant SFT in the pelvic

cavity. Prior to the operation, the scores of IPSS, QOL index,

OABSS, and IIEF-5 were 19, 6, 11 and 14, respectively. Six months

after the operation the scores had changed to 1, 0, 1 and 13,

respectively. Moreover, max flow rate, voiding time and residual

urine were 18 ml/sec, 19 sec and 35 ml. The patient showed no sign

of recurrence 12 months after surgery and required no additional

therapy.

Discussion

Since the initial description that SFT originates in

the pleura, SFTs have been reported to occur in a wide range of

anatomic sites (1,2). Among extrathoracic SFTs, primary SFT

in the pelvic cavity occurred in 16% of 79 cases of SFTs involving

various sites (2). The key symptoms

of abdominal SFTs are abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, or a

palpable abdominal mass. Hypoglycemia occurred in 4% of 360 cases

of SFTs of the pleura (6). In the

present case, no hypoglycemia was detected. The symptom of the

present case was urinary retention caused by tumor pressure on the

urethra. However, no previous cases of SFT with the symptom of

urinary retention were found in the literature. CT imaging of SFT

usually revealed a well-delineated, homogeneous, and occasionally

lobulated mass of soft tissue attenuation (7), and MRI revealed fibrous tissue of SFT

with a low signal intensity on T1-weighted images. However, mature

fibrous tissue has a low intensity, while malignant fibrous tissue

tends to exhibit a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images

(4). Although the radiological

findings in our case were typical of SFT, we performed US-guided

needle biopsy for diagnosis since cases of SFT are rare. The

pathological features of SFT were a ‘patternless pattern’

characterized by a haphazard, storiform arrangement of short

spindle or ovoid cells, and a ‘hemangiopericytoma-like appearance’

with prominent vascularity by thin-walled vessels (8).

Immunohistochemical examination of proteins, such as

CD34 and bcl-2, has been found to be helpful for diagnosing SFT

(8). In their study, England et

al reported that more than one-third of pleural SFTs are

histologically malignant, and proposed pathological criteria for

malignant SFT such as high cellularity with crowded and overlapping

nuclei and over 4 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields.

However, the clinical features of retroperitoneal SFT are not

necessarily concordant with morphologic evaluations, and most

extrapleural SFTs in previous reports, even with malignant

histological features, showed a benign nature. Some investigators

stressed that intraoperative findings and surgical resectability

are more reliable prognostic factors based on the experience of a

small number of patients with recurrent or metastasized SFT

(9). SFTs have a low rate of local

recurrence and metastasis following surgical resection. However,

tumors larger than 10 cm or those demonstrating a histologically

malignant component have an increased risk of local recurrence and

metastasis. Complete en bloc surgical resection is the

standard therapy for SFT. We performed complete resection of the

tumor without any adhesion, and the pathological finding of margin

was negative for tumor cells in the present case. In addition,

surrounding tissue and peritoneum was not damaged when resecting

the pelvic mass, preserving the neural network connected to urinary

and erectile functions in the pelvic cavity. Urinary function

improved and erectile function remained good following the

operation. In the anatomical study, a fat layer tissue was revealed

between the peritoneum and bladder wall (Fig. 3). Consequently, we were able to

perform abruption between the bladder and peritoneum and enter the

retroperitoneum. Takizawa et al reported that

retroperitoneal SFTs required less adhesion than tumors of other

histotypes at the same location, including liposarcoma, leiomyomas,

leiomyosarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, nerve sheath

tumors, and germ cell tumors (10).

We propose that pelvic SFTs detected with no adhesion in and around

the tumor can be completely resected with ease, while preserving

the neural network connected to urinary and erectile functions in

the pelvic cavity.

References

|

1

|

Klemperer P and Rabin CB: Primary neoplasm

of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 11:385–412.

1931.

|

|

2

|

Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, et al:

Clinicopathological correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer.

94:1057–1068. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Suster S, Nascimento AG, Miettinen M, et

al: Solitary fibrous tumors of soft tissue. A clinicopathological

and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

19:1257–1266. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nagase T, Adachi I, Yamada T, et al:

Solitary fibrous tumor in the pelvic cavity with hypoglycemia:

report of a case. Surg Today. 35:181–184. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

England DM, Hochholzer L and McCarthy MJ:

Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A

clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

13:640–658. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Briselli M, Mark EJ and Dickersin GR:

Solitary fibrosis tumors of the pleura: eight new cases and review

of 360 cases in the literature. Cancer. 47:2678–2689. 1981.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee KS, Im JG, Choe KO, Kim CJ and Lee BH:

CT findings in benign fibrous mesothelioma of the pleura. Am J

Roentgenol. 158:983–986. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yamashita S, Tochigi T, Kawamura S, et al:

Case of retroperitoneal solitary fibrous tumor. Hinyoukika Kiyo.

53:477–480. 2007.

|

|

9

|

Morimitsu Y, Nakajima M, Hisaoka M, et al:

Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: clinicopathologic study of 17

cases and molecular analysis of the p53 pathway. Acta Pathol

Microbiol Immunol Scand Suppl. 108:617–625. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Takizawa I, Saito T, Kitamura Y, et al:

Primary solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) in the peritoneum. Urol Oncol.

26:254–259. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|