Contents

Introduction

Overview of AIB1 structure and function

Implication of AIB1 in breast cancer

Conclusion

Introduction

Amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1), also known as

steroid receptor coactivator-3 (SRC-3), nuclear receptor

coactivator-3 (NCoA-3), receptor associated coactivator-3 (RAC-3),

activator of thyroid hormone and retinoid receptor (ACTR), thyroid

hormone receptor activating molecule-1 (TRAM-1) and p300/CBP

interacting protein (p/CIP) is a member of the p160 nuclear

receptor coactivator family (1).

Other members of this family include SRC-1 and SRC-2. The

AIB1 gene is located on chromosome 20q12-12, and it was

first identified in human breast cancer cells, where approximately

10% of these cells revealed amplification of the gene and 64%

revealed overexpression of the protein (2). AIB1 was later considered as an

oncogene since overexpression of AIB1 in mice led to the

spontaneous development of malignant mammary tumors (3), whereas AIB1−/− mice were

resistant to chemical carcinogen-induced mammary tumorigenesis

(4,5). However, AIB1 also acts as a tumor

suppressor since deletion of the AIB1 gene in B-cell

lymphoma mice led to the development of B-cell lymphomas (6). Furthermore, results from cell culture

systems and targeted gene disruption experiments in mice have

demonstrated that AIB1 also plays an essential role in the female

reproductive function, puberty, cytokine signaling and

vasoprotection (7). The correlation

between AIB1 and cancer has been widely investigated since it was

shown to be amplified in breast cancer. Initially, AIB1 was thought

to promote cancer development through hormone-dependent pathways

since it acts as a transcriptional coactivator for nuclear

receptors in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer.

However, various non-nuclear receptor transcription factors, such

as E2F1, p53 and NF-κB were found to be coactivated by AIB1, which

provides supporting evidence that AIB1 also influences the progress

of cancer cells through hormone-independent pathways (8–10).

Over the past decade, numerous reviews focusing on the function of

AIB1 and its role in cancer have been published (11–19).

The focus of this review is to highlight the important progress

made with recent findings and to present an overview of the current

understanding of the signaling pathways through which the influence

of AIB1 leads to the development and progression of breast

cancer.

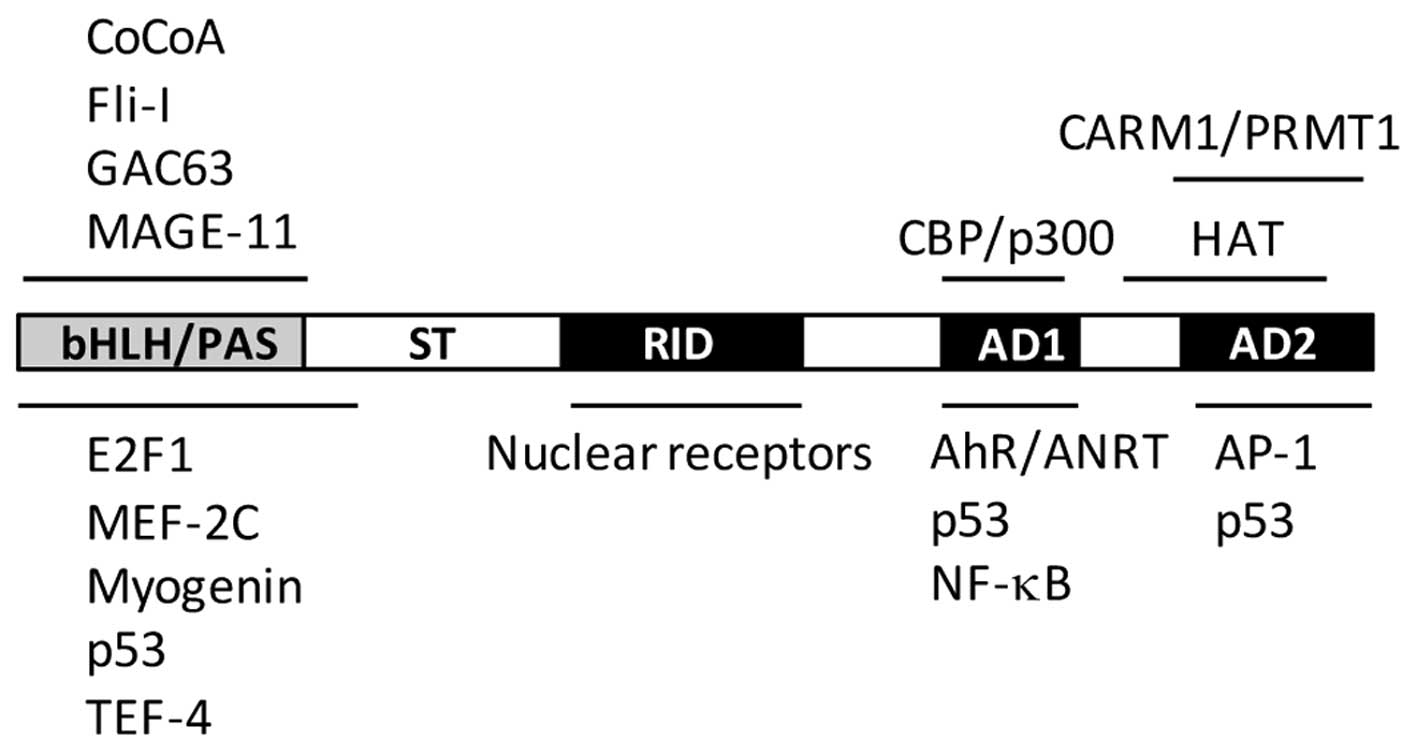

Overview of AIB1 structure and function

Structural domains of AIB1 and its

functions

AIB1 is approximately 160 kDa in size and its

structure is conserved across different species. The structure of

AIB1 consists of a central nuclear receptor interaction domain

(NID), an N-terminal basic helix-loop-helix/Per-ARNT-Sim (bHLH/PAS)

domain and two activation domains, known as AD1 and AD2, located in

the C-terminal region (Fig. 1). In

addition, it also contains a serine/threonine-rich domain in the

N-terminus, a glutamine (Q)-rich domain, and a histone

acetyltransferase (HAT) domain in the C-terminus. The relatively

conserved NID domain mainly mediates direct interaction between

AIB1 and nuclear receptors, such as ER and androgen receptor (AR)

through ligand-dependent pathways. Analysis of the NID sequence has

revealed three conserved LXXLL motifs (where L is leucine and X is

any amino acid) that act as a nuclear receptor box (20). These three LXXLL motifs form an

amphipathic α-helix in the secondary structure, which then allows

the conserved leucines to form a hydrophobic surface that mediates

the binding of ligands to the ligand-binding domain of nuclear

receptors (13).

The bHLH/PAS domain of AIB1 is conserved in the SRC

family with a sequence similarity of approximately 60%. This domain

mediates protein-protein interactions that result in the

recruitment of other coactivators. The AD1 domain, also named

CBP-interaction domain (CID), is involved in direct interaction

with the general transcriptional cointegrators, CBP/p300 and PCAF,

without interacting with nuclear receptors (21). The AD1 domain also contains three

LXXLL/LXXLL-like motifs, which are crucial in promoting the

interaction between AIB1 and p300 (22,23).

The AD2 domain is mainly responsible for the interaction with

histone methyltransferases, including coactivator-associated

arginine methyltransferase-1 (CARM1) and protein arginine

methyltransferase-1 (PRMT1) (24–26).

The HAT activity of the C-terminal domain of AIB1 is weaker than

that of CBP/p300 and PCAF, and its importance in AIB1

transcriptional activation has yet to be clarified (27–29).

The structure and function of AIB1 has previously been extensively

reviewed (11,17).

Importance of post-translational

modification

Certain serines and threonines in the

serine/threonine-rich domain are also sites of phosphorylation.

In vitro phosphorylation of AIB1 converts it into a potent

transcriptional activator, thereby modifying its oncogenic

potential and leading to differential gene expression (30). Phosphorylation of tyrosine residue

(Y1357) in the AD2 domain by AbI kinase is required for its

activity in cancer cells (31).

Dephosphorylation of AIB1 by phosphatases has been shown to be

critical for regulating its function and preventing its

proteasome-dependent turnover (32), and phosphorylation by atypical

protein kinase C (aPKC), which is frequently overexpressed in

cancers, specifically stabilizes AIB1 in an ER-dependent manner

through coordinating the inhibition of both ubiquitin-dependent and

ubiquitin-independent degradations (33). The turnover of activated AIB1 during

tumorigenesis has recently been shown to be mediated by

speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP), which is a cullin 3-based

ubiquitin ligase (34). A high

percentage of loss of heterozyogisty at the SPOP locus was found in

breast cancers, and restoration of its expression resulted in the

suppression of AIB1-mediated oncogenic signaling and

tumorigenesis.

Our previous study demonstrated that phosphorylation

of AIB1 is accompanied by a loss in sumoylation and an increase in

its transactivation, while dephosphorylation is accompanied by a

concomitant increase in sumoylation and reduced transactivation

(35). We have recently reported

that sumoylation of AIB1 requires the SUMO E3 PIAS1, which

coprecipitated with AIB1 in extract prepared from MCF-7 cells, and

that overexpression of PIAS1 and AIB1 in MCF-7 cells led to

increased sumoylation of AIB1, resulting in repression of its

transcriptional activity (36).

PIAS1 also increased the stability of AIB1 and attenuated its

interaction with ERα. These findings suggest that PIAS1 may play a

crucial role in the regulation of AIB1 transcriptional activity and

its interaction with accessory proteins through sumoylation.

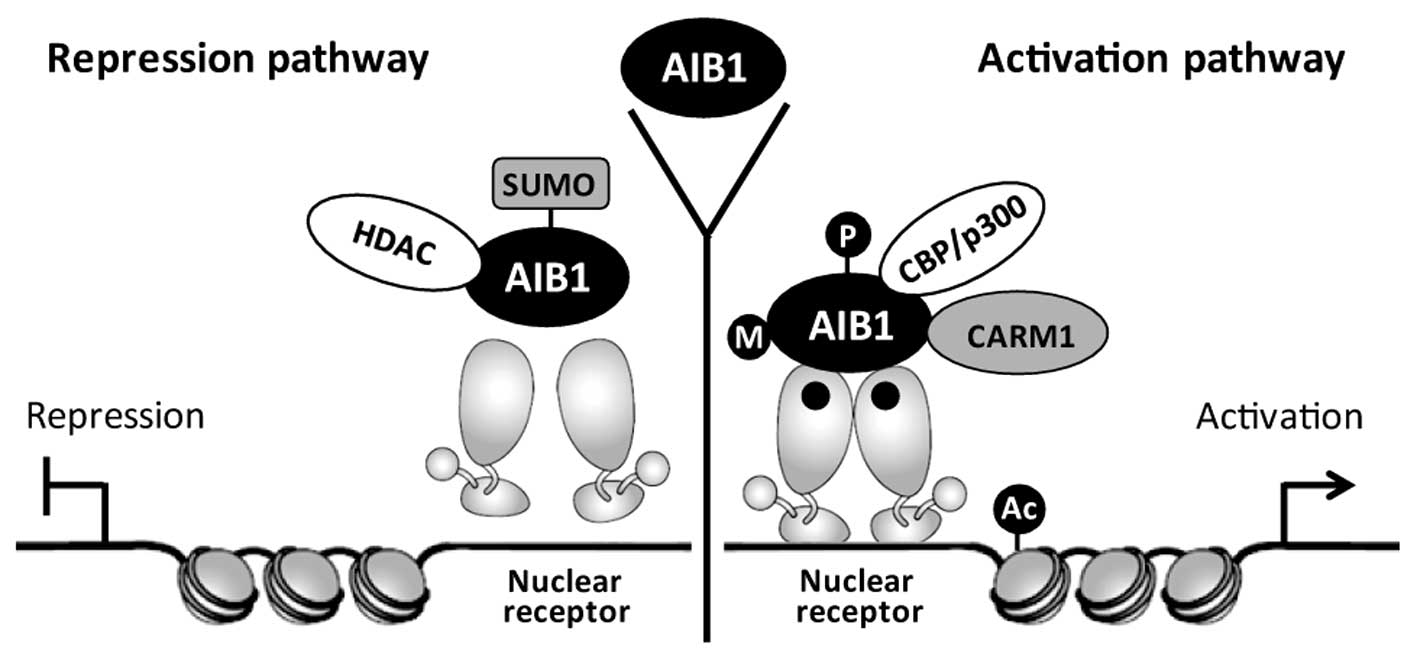

As an ER coactivator, AIB1 regulates ER

transcriptional activity through recruitment of the histone

acetyltransferases CBP/p300 and PCAF. Acetylation of histones could

modify chromatin structure and facilitate ER to bind at the

promoters of downstream target genes, leading to enhanced

expression of cancer genes. Through sequencing and mapping of

genomic DNA fragments obtained by AIB1 ChIP assays, Labhart et

al (37) identified 18 putative

AIB1 target genes based on their strong AIB1-binding sites, and

demonstrated ERα binding with all of these genes. AIB1 also

promotes certain transcription factors to interact with other

transcription cofactors and this process is regulated by

post-translational modifications, including methylation,

sumoylation, phosphorylation and acetylation (38). The transcriptional complex of AIB1

in hormone-induced gene expression mediated by the nuclear receptor

is shown in Fig. 2.

Implication of AIB1 in breast cancer

AIB1 and hormone-dependent breast

cancer

The AIB1 gene is amplified in approximately

5–10% of human breast cancers and is overexpressed at both the mRNA

(as high as 60%) and protein levels in approximately 30% of breast

cancers (2,39–43).

Further study has revealed that overexpression of AIB1 is

correlated with tumor recurrence and survival (44). Increases in AIB1 transcript levels

in human breast tumors may also occur by mechanisms other than gene

amplification, such as overexpression of AIB1 mRNA resulting from a

loss of ER expression in breast tumor samples (45). A recent study investigating the

prognostic significance of AIB1 and its correlation with various

steroid hormone receptors (ER, PR, AR, DAX-1 and HER2) shows that

for patients suffering from ER-negative breast cancers, strong AIB1

protein expression is correlated with poorer overall survival

(46). Besides breast cancer,

amplification of AIB1 has also been detected in many other

hormone-sensitive tumors, including prostate and ovarian cancers

(2,47).

As a member of the steroid receptor coactivator

family, AIB1 is essential for the transcriptional activity of

certain nuclear receptors (including ERα), which control processes

important for development, homeostasis and reproduction (48). AIB1 is considered to play

significant roles in ER-positive breast cancers. The level of ER in

breast cancer is considered to be an important marker for most

breast cancer therapy and prognosis. As a coactivator for ER, AIB1

is thought to influence the growth of hormone-dependent breast

cancer through mediating the effects of estrogen on ERα-dependent

gene expression (2,41), and this serves as a mechanism by

which AIB1 modulates the growth of hormone-dependent breast cancer.

This mechanistic model is supported by a study showing that

depletion of AIB1 may inhibit estrogen-stimulated cell

proliferation and survival in ER-positive MCF-7 human breast cancer

cells, leading to a decrease in growth of MCF-7 xenografts in mice

(49,50). However, not all ERα-positive breast

cancers are associated with higher levels of AIB1 mRNA, as

ERα-negative breast cancer has also been found to be associated

with high levels of AIB1 mRNA (14). Discrepancy among these studies is

thought to be caused by differences in the role and regulation of

AIB1 and the hormone receptors at different stages of breast

cancer. A recent study has uncovered evidence of an association

between silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone

receptor (SMRT) with AIB1 in the regulation of ER-dependent gene

expression, such as the expression of progesterone receptor and

cyclin D1 genes (51). SMRT is able

to bind directly to AIB1 independently of ER, and this complex then

promotes the subsequent E2-dependent binding of AIB1 to ER,

demonstrating that SMRT promotes ER- and AIB1-dependent gene

expression in breast cancer.

The correlation between AIB1 and breast cancer has

also been investigated using several AIB1-depleted mouse models. In

mice harbouring the mouse mammary tumor virus/v-Ha-ras (ras)

transgene, breast tumor incidence was notably reduced in intact

AIB1−/− -ras virgin mice compared to complete inhibition

in ovariectomized AIB1−/− -ras mice (4). Furthermore, the level of IGF-1

expression and insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 and -2 proteins

in the mammary glands and tumors of these mice were significantly

reduced, which contributed in part to the suppression of mammary

tumorigenesis and metastasis. In another model, mice lacking AIB1

were shown to be resistant to chemical carcinogen-induced mammary

tumorigenesis (5). In a different

mouse model, deletion of one allele of AIB1 in MMTV-Neu mice was

found to significantly delay Neu-induced mammary tumor development,

demonstrating that AIB1 is required for Neu (ErbB2/HER2)

activation, signaling and mammary tumorigenesis (52). Although these animal models have

provided important data on the involvement of AIB1 in breast cancer

by allowing the disease to be simulated or recreated under

controlled conditions, they still do not represent the real

condition of the disease in the case of humans, and at best, should

only be regarded as a mimic. Thus, what have been learned from

animal models may not necessarily be completely applicable to

humans.

AIB1 also appears to play a significant role in the

resistance of breast cancer to anti-estrogen therapy. Over the past

few decades, tamoxifen has been the standard endocrine therapy for

treating ER-positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen is a non-steroidal

estrogen receptor antagonist (but also exhibits agonist activity)

and functions by competitively blocking the binding of estrogen to

ER, thereby inhibiting estrogen-mediated gene expression and

estrogen-dependent cell growth (53). However, the use of tamoxifen has

gradually led to the emergence of tamoxifen resistance in breast

cancer. The involvement of AIB1 in tamoxifen resistance has been

demonstrated in breast cancer patients, whereby disease-free and

overall survival is correlated with high expression of AIB1. There

is also evidence linking the expression of AIB1 protein and breast

tumor recurrence in ErbB2-positive breast tumors, and knockdown of

AIB1 in tamoxifen-resistant, ErbB2-positive breast cancer cell line

BT474 restored its sensitivity to tamoxifen (54). These results appear to indicate that

the expression of AIB1 is associated with resistance to tamoxifen

for ER-positive breast cancer patients undergoing tamoxifen

treatment. The underlying mechanism for tamoxifen resistance has

been further clarified by data obtained from an in vivo

breast tumor model, which showed that tamoxifen resistance in

ER-positive breast cancer is also mediated by EGFR/HER2, even

though ER genomic function is suppressed by tamoxifen (55). In a recent study, Karmakar et

al (56) evaluated the role of

AIB1 and two other SRC coactivators in the growth of the

estrogen-independent and tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cell

line LCC2 and found that these coactivators exert a mixture of

ligand-dependent and ligand-independent effects on the regulation

of cell growth and apoptosis. Furthermore, these authors

demonstrated that growth of LCC2 cells is controlled by AIB1 and

SCR-2, largely through the control of basal cell growth, and

suggested that targeting growth inhibition via SRC-2 and AIB1 may

offer a more effective way to inhibit the growth of

tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Resistance to tamoxifen is now

being viewed as a result of crosstalk between ER and growth factor

signaling pathways (57,58). AIB1 is considered to play a positive

role in tamoxifen resistance since overexpression of AIB1 alone has

been shown to increase the agonist properties of tamoxifen in

breast cancer cell lines (59).

Taken together, these existing findings support the notion that

tamoxifen resistance is a product of multiple mechanisms, and that

AIB1 appears to play an important role; however, further

investigation is required to provide a more definitive

understanding of its underlying mechanism.

A more recent study concerned with the global

characterization of the transcriptional impact of AIB1 has shed

more light on the scope of AIB1 target genes and provides a

molecular framework for AIB1 in interpreting estrogen signaling

(60). This study, which combines

genome-wide mapping of AIB1 affinity sites in MCF-7 cells with RNA

expression signatures and a proteomic approach, is so far the most

sophisticated study to identify the transcriptional regulatory

network of AIB1. It also opens up new areas for exploring the

hormone-dependent signaling of breast cancer afforded by AIB1.

AIB1 and hormone-independent breast

cancer

Although AIB1 levels have been shown to be a

limiting factor for ER-positive breast cancer growth through

hormone-dependent pathways, substantial evidence has suggested that

AIB1 stimulates the growth of cancer cells through

hormone-independent pathways. For example, in a recent study,

Torres-Arzayus et al (61)

addressed the role of estrogen and ERα in AIB1-mediated tumor

formation and showed that AIB1 transgenic mice that had their

ovaries removed at the prepubertal stage to block estrogen

production did not develop any invasive mammary gland tumors.

However, these animals showed higher incidence of pituitary, lung,

skin and bone tumors than their non-ovariectomized counterparts.

They also crossed AIB1 transgenic mice with ERα-null mutant mice

and found that mice lacking ERα were unable to respond to estrogen

through this receptor. At the same time, these animals showed no

signs of mammary tumors but developed tumors in the lung, skin, and

pituitary gland with the same incidence as their ERα-positive AIB1

transgenic counterparts. The authors concluded from these findings

that depending on the organ or tissue affected, AIB1 causes tumor

formation by estrogen-dependent and estrogen-independent

mechanisms, and that AIB1 exerts its oncogenic activities in cell

signaling that are independent of its function as an ER

coactivator. Other studies have also indicated the involvement of

AIB1 in breast cancer through certain hormone-independent pathways,

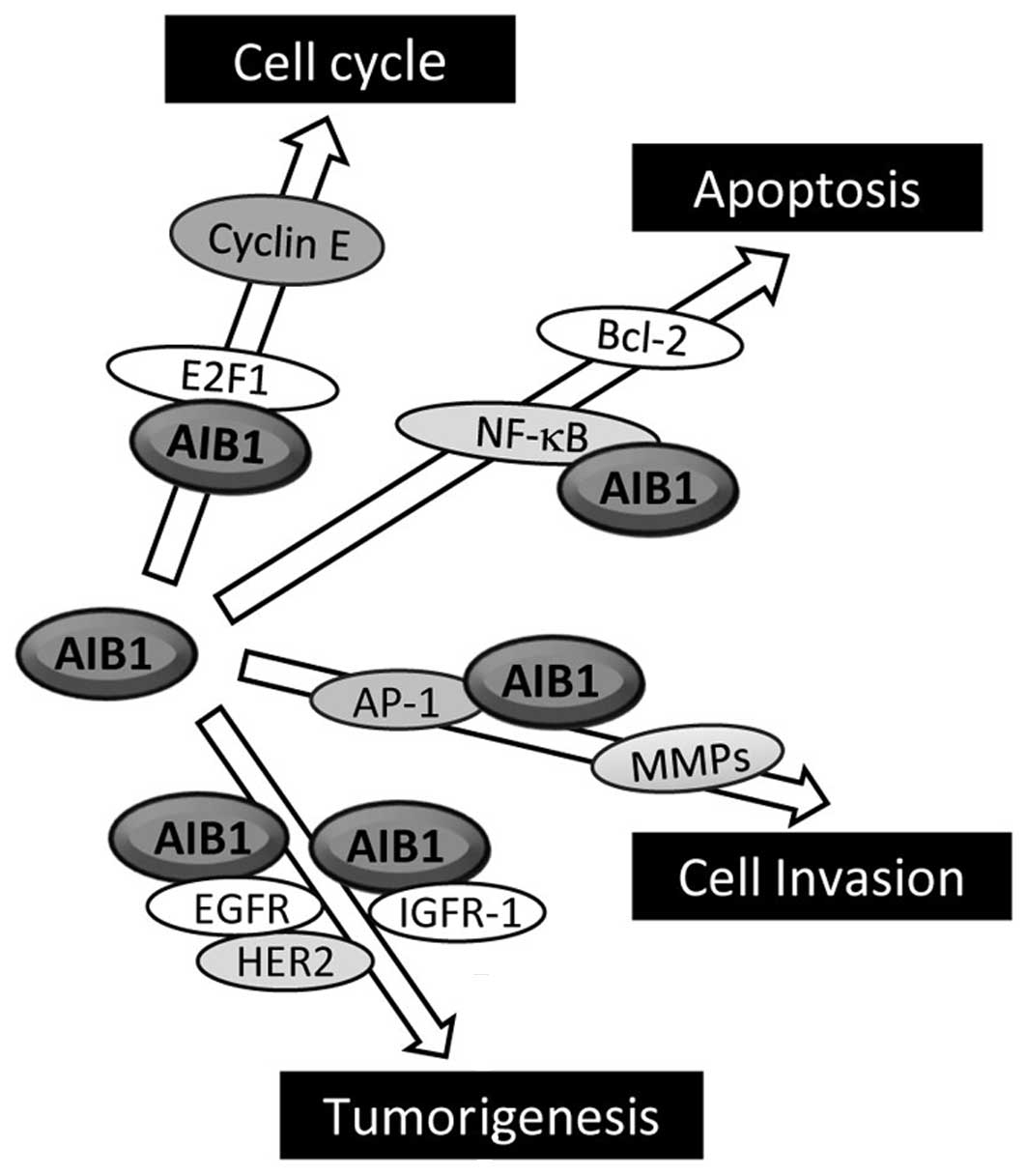

including E2F1, IGF-I and EGF signaling (Fig. 3) (7,62).

Overexpression of AIB1 has been found to increase

cell proliferation even in the presence of nuclear receptor

antagonist (9). More convincingly,

the overexpression of AIB1 promotes the growth of

hormone-independent cancer cells through enhancing the

transcription of E2F target genes, which are mostly G1/S cycle

transition-related proteins, such as E2F1, cyclin E and

cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) (9). AIB1 interacts with the transcriptional

factor E2F1, and this then results in the recruitment of AIB1 to

the E2F-binding sites on the target gene promoters, eventually

leading to activation of these E2F-dependent downstream genes.

Notably, AIB1 promotes its own transcription with E2F1, and this

positive feedback regulatory loop is thought to enhance the

influence AIB1 exerts on cell cycle control. Overexpression of AIB1

has also been found to correlate with high levels of p53 proteins

in invasive breast cancer cells (45).

The association of AIB1 with the regulation of IGF-I

signaling in cancer is supported by the finding that AIB1 knockout

downregulates the expression levels of both IGF-I mRNA and protein,

whereas overexpression of AIB1 has the opposite effect (63). In addition, AIB1 may also regulate

the expression of many IGF-I signaling components, including IGF-I

receptor β (IGF-IRβ), IRS-1 and IRS-2 in vitro and in

vivo. Although the mechanism as to how AIB1 modulates IGF-I

signaling in cancers is not clear, it has been reported that AIB1

binds to the transcription factor AP-1 and promotes AP-1-mediated

transcription of IGF-I and IRS-1 (64). In addition, AIB1 knockout mice have

an impaired ability in their response to IGF-I stimulation and are

unresponsive to IGF-I-induced DNA synthesis. This may in part be

explained by the result from the study conducted by Liao et

al (65), which shows that

AIB1−/− mice have lower levels of circulating IGF-I

compared to wild-type mice, a consequence of rapid IGF-I

degradation rather than lower expression. The rapid IGF-I

degradation is caused by a lack of expression of IGF-binding

protein 3 (IGFBP-3), which is induced by vitamin D through a

vitamin D receptor (VDR). These results point to a role of AIB1 in

maintaining the circulating level of IGF-I through increasing

VDR-regulated IGFBP-3 expression. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is also

associated with AIB1-mediated tumorigenesis, since it was shown

that mammary hyperplasia and hypertrophy induced in mice via

overexpression of AIB1 can be prevented by inhibition of mTOR with

the rapamycin analog RAD001 (66).

RAD001 also inhibits the growth of AIB1-induced tumor xenografts in

mice.

EGF signaling is known to play a crucial role in the

initiation and progression of breast cancer (67). The influence of AIB1 on breast

cancer via EGF signaling is supported by a study showing that AIB1

knockdown by siRNA reduced EGF-mediated phosphorylation of EGFR and

HER-2, leading to inhibition of the activation of EGF signaling in

lung, pancreatic and breast cancer cells and confirming that AIB1

regulates EGF signaling to promote the proliferation of cancer

cells (68). Taken together, these

studies indicate that the role of AIB1 extends beyond the actions

of steroid hormone receptors in cancer cells.

The role of AIB1 in cancer progression

and metastasis

AIB1 plays a significant role in mammary tumor

progression and metastasis through mediating tumor cell motility

and invasion (18,43,69).

AIB1−/− mice harboring the mouse mammary tumor

virus-polomavirus middle T (PyMT) transgene or

AIB1−/−/PyMT human tumor cells were found to have

reduced expression of MMP2 and MMP9, resulting in lower

cell-invasive and metastatic capabilities (43). AIB1 acts as a PEA3 coactivator by

forming complexes with PEA3 on MMP2 and MMP9 promoters to enhance

their expression in both mouse and human breast cancer cells.

Furthermore, a AIB1 splice isoform lacking the N-terminal bHLH

domain (due to the deletion of exon 4) that is overexpressed in

breast cancer cells and tumors has also been shown to play critical

roles in promoting cancer cell proliferation, invasion and

metastasis through acting as a missing adaptor protein that bridges

the interaction between EGFR and FAK (a non-receptor tyrosine

kinase) following EGF stimulation (69).

Influence of AIB1 on tumor suppressor

gene and cancer

A hallmark of cancer is often an improper balance

between cell proliferation and apoptosis. Oncogene activation

coupled with loss of tumor suppressor function would enable the

cell to escape senescence and apoptosis, thereby providing an

advantage for tumorigenesis. A number of studies have demonstrated

the involvement of AIB1 in apoptosis. For example, knockdown of

AIB1 by siRNA in human chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cells reduces

activation of NF-κB signaling, ultimately leading to apoptosis

(70), while overexpression of AIB1

in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells has the reverse effect

(71). A study by Ferragud et

al (72) revealed that AIB1

acts as a negative regulator for DROI, a tumor suppressor gene that

was first identified as upregulated in brown adipose tissue of mice

deficient in bombesin receptor subtype-3 (73). The function of DROI as a tumor

suppressor gene was later demonstrated when its expression was

shown to be highly reduced in colon and pancreatic cancers

(74). Further investigation

revealed that DROI plays an important role in adipogenesis through

downregulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling and inducing C/EBPα and

PPARγ (75). The expression of DROI

was significantly reduced in mouse mammary epithelial cells or

human primary cultures overexpressing AIB1 (72). Furthermore, DROI expression levels

decreased in MCF-7 cells treated with estrogen but increased when

treated with tamoxifen. Another study identified the tumor

suppressor 53BP1 (a DNA-damaging response protein) as a novel

AIB1-interacting protein, and through chromatin immunoprecipitation

(ChIP) and siRNA knockdown experiments, AIB1 and 53BP1 were shown

to co-occupy the same region of the breast cancer type 1

susceptibility protein (BRCA1) promoter, and both proteins were

required for BRCA1 expression in HeLa cells (76). There was no evidence to indicate

that AIB1 plays a direct role in DNA damage response; however,

these authors concluded that the association between 53BP1 and AIB1

may modulate the transcriptional response of the BRCA1 gene

and possibly regulate the activity of a subset of target genes

involved in DNA repair. Taken together, these results demonstrate

yet another mechanistic feature of AIB1 in cancer development, one

that occurs via its suppression of tumor suppressor genes.

Conclusion

For the past few decades, endocrine therapy has been

the most effective treatment for women with ER-positive breast

cancer. However, the emergence of resistance to endocrine therapy

has prompted the search for a different strategy, which involves

targeting both ER and growth factor receptor signaling (77). Therapeutic approaches that

simultaneously target ER and components of growth factor signaling,

such as EGFR, HER2 and PI3K, have had some success in the

preclinical setting. However, extensive further study is required

to take this approach beyond the preclinical setting. As far as the

role of AIB1 in breast cancer is concerned, given the pleiotropic

effect of this coactivator and the complexity of the signaling

network that it participates in and regulates, it becomes a great

challenge to conceive of a long-term therapeutic strategy that

effectively eliminates the cancer and prevents recurrence of the

disease. Post-translational modification of AIB1 in the form of

phosphorylation and its relevance to cancer is still not fully

elucidated, and there has been suggestion that if the phosphoforms

of AIB1 are important in human malignant disease then targeting

these phosphoforms of AIB1 may be a useful therapeutic approach

(17). Interrupting nuclear

receptor coactivator interactions has been suggested to be

beneficial in treating nuclear receptor-mediated diseases,

including breast cancer (19).

However, specifically targeting AIB1 or any of its associated

transcription factors, coactivators or accessory proteins is

unlikely to be effective, since such a measure is likely to upset

the overall cellular reaction network in the long term, resulting

in potential side effects. Nevertheless, future research should

focus on gaining more insight into the mechanistic functions and

regulations of AIB1, particularly those concerned with its

dysfunctions that ultimately trigger the onset of cancers. Studies

on the post-translational modifications (including sumoylation,

which still requires extensive research) that govern the regulation

and turnover of the AIB1 protein with respect to its modulation of

cancer development and progression are also important and relevant

to the overall therapeutic strategy for combating breast cancers

mediated by this transcriptional coactivator.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant

(30771221 to H.W.) from the National Natural Science Foundation of

China and a grant (973 Program 2011CB504201 to H.W.) from the

Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

References

|

1.

|

J XuQ LiReview of the in vivo functions of

the p160 steroid receptor coactivator familyMol

Endocrinol1716811692200310.1210/me.2003-011612805412

|

|

2.

|

SL AnzickJ KononenRL WalkerDO AzorsaMM

TannerXY GuanG SauterOP KallioniemiJM TrentPS MeltzerAIB1, a

steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian

cancerScience277965968199710.1126/science.277.5328.9659252329

|

|

3.

|

MI Torres-ArzayusJ Font de MoraJ YuanF

VazquezR BronsonM RueWR SellersM BrownHigh tumor incidence and

activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1

as an oncogeneCancer

Cell6263274200410.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.02715380517

|

|

4.

|

SQ KuangL LiaoH ZhangAV LeeBW O'MalleyJ

XuAIB1/SRC-3 deficiency affects insulin-like growth factor 1

signaling pathway and suppresses v-Ha-ras-induced breast cancer

initiation and progression in miceCancer

Res6418751885200410.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-374514996752

|

|

5.

|

SQ KuangL LiaoS WangD MedinaBW O'MalleyJ

XuMice lacking the amplified in breast cancer 1/steroid receptor

coactivator-3 are resistant to chemical carcinogen-induced mammary

tumorigenesisCancer Res6579938002200516140972

|

|

6.

|

A CosteMC AntalS ChanP KastnerM MarkBW

O'MalleyJ AuwerxAbsence of the steroid receptor coactivator-3

induces B-cell lymphomaEMBO

J2524532464200610.1038/sj.emboj.760110616675958

|

|

7.

|

G MaY RenK WangJ HeSRC-3 has a role in

cancer other than as a nuclear receptor coactivatorInt J Biol

Sci7664672201110.7150/ijbs.7.66421647249

|

|

8.

|

S WerbajhI NojekR LanzMA CostasRAC-3 is a

NF-kappa B coactivatorFEBS

Lett485195199200010.1016/S0014-5793(00)02223-711094166

|

|

9.

|

MC LouieJX ZouA RabinovichHW ChenACTR/AIB1

functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell

proliferation and antiestrogen resistanceMol Cell

Biol2451575171200410.1128/MCB.24.12.5157-5171.200415169882

|

|

10.

|

H YamashitaS TakahashiY ItoT YamashitaY

AndoT ToyamaH SugiuraN YoshimotoS KobayashiY FujiiH IwasePredictors

of response to exemestane as primary endocrine therapy in estrogen

receptor-positive breast cancerCancer

Sci10020282033200910.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01274.x19659610

|

|

11.

|

L LiaoSQ KuangY YuanSM GonzalezBW

O'MalleyJ XuMolecular structure and biological function of the

cancer-amplified nuclear receptor coactivator SRC-3/AIB1J Steroid

Biochem Mol Bio83314200210.1016/S0960-0760(02)00254-612650696

|

|

12.

|

J YanSY TsaiMJ TsaiSRC-3/AIB1:

transcriptional coactivator in oncogenesisActa Pharmacol

Sin27387394200610.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00315.x16539836

|

|

13.

|

L AmazitL PasiniAT SzafranV BernoRC WuM

MielkeED JonesMG ManciniCA HinojosBW O'MalleyMA ManciniRegulation

of SRC-3 intercompartmental dynamics by estrogen receptor and

phosphorylationMol Cell

Biol2769136932200710.1128/MCB.01695-0617646391

|

|

14.

|

T LahusenRT HenkeBL KaganA WellsteinAT

RiegelThe role and regulation of the nuclear receptor co-activator

AIB1 in breast cancerBreast Cancer Res

Treat116225237200910.1007/s10549-009-0405-219418218

|

|

15.

|

J XuRC WuBW O'MalleyNormal and

cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator

(SRC) familyNat Rev Cancer9615630200910.1038/nrc269519701241

|

|

16.

|

O GojisB RudrarajuC AlifrangisJ KrellP

LibalovaC PalmieriThe role of steroid receptor coactivator-3

(SRC-3) in human malignant diseaseEur J Surg

Oncol36224229201010.1016/j.ejso.2009.08.00219716257

|

|

17.

|

O GojisB RudrarajuM GudiK HogbenS SoushaRC

CoombesS CleatorC PalmieriThe role of SRC-3 in human breast

cancerNat Rev Clin

Oncol78389201010.1038/nrclinonc.2009.21920027190

|

|

18.

|

JP LydonBW O'MalleyMinireview: steroid

receptor coactivator-3: a multifarious coregulator in mammary gland

metastasisEndocrinology1521925201110.1210/en.2010-101221047941

|

|

19.

|

AB JohnsonBW O'MalleySteroid receptor

coactivators 1, 2, and 3: critical regulators of nuclear receptor

activity and steroid receptor modulator (SRM)-based cancer

therapyMol Cel

Endocrinol348430439201210.1016/j.mce.2011.04.02121664237

|

|

20.

|

RS SavkurTP BurrisThe coactivator LXXLL

nuclear receptor recognition motifJ Pept

Res63207212200410.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00126.x15049832

|

|

21.

|

H ChenRJ LinRL SchilzD ChakravartiA NashL

NagyML PrivalskyY NakataniRM EvansNuclear receptor coactivator ACTR

is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric

activation complex with p/CAF and

CBP/300Cell90569580199710.1016/S0092-8674(00)80516-49267036

|

|

22.

|

JJ VoegelMJ HeineM TiniV VivatP ChambonH

GronemeyerThe coactivator TIF2 contains three nuclear

receptor-binding motifs and mediates transactivation through CBP

binding-dependent and -independent pathwaysEMBO

J17507519199810.1093/emboj/17.2.507

|

|

23.

|

J LiBW O'MalleyJ Wongp300 requires its

histone acetyltransferase activity and SRC-1 interaction domain to

facilitate thyroid hormone receptor activation in chromatinMol Cell

Biol2020312042200010.1128/MCB.20.6.2031-2042.2000

|

|

24.

|

C QiJ ChangY ZhuAV YeldandiSM RaoYJ

ZhuIdentification of protein arginine methyltransferase 2 as a

coactivator for estrogen receptor alphaJ Biol

Chem2772862428630200210.1074/jbc.M20105320012039952

|

|

25.

|

C TeyssierD ChenMR StallcupRequirement for

multiple domains of the protein arginine methyltransferase CARM1 in

its transcriptional coactivator functionJ Biol

Chem2774606646072200210.1074/jbc.M20762320012351636

|

|

26.

|

DY LeeC TeyssierBD StrahlMR StallcupRole

of protein methylation in regulation of transcriptionEndocr

Rev26147170200510.1210/er.2004-000815479858

|

|

27.

|

TE SpencerG JensterMM BurcinCD AllisJ

ZhouCA MizzenNJ McKennaSA OnateSY TsaiMJ TsaiBW O'MalleySteroid

receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyl

transferaseNature389194198199710.1038/383049296499

|

|

28.

|

D ChenH MaH HongSS KohSM HuangBT

SchurterDW AswadMR StallcupRegulation of transcription by a protein

methyltransferaseScience28421742177199910.1126/science.284.5423.217410381882

|

|

29.

|

SS KohD ChenYH LeeMR StallcupSynergistic

enhancement of nuclear receptor function by p160 coactivators and

two coactivators with protein methyltransferase activitiesJ Biol

Chem27610891098200110.1074/jbc.M00422820011050077

|

|

30.

|

RC WuCL SmithBW O'MalleyTranscriptional

regulation by steroid receptor coactivator phosphorylationEndocr

Rev26393399200510.1210/er.2004-001815814849

|

|

31.

|

AS OhJT LahusenCD ChienMP FereshtehX

ZhangS DakshanamurthyJ XuBL KaganA WellsteinAT RiegelTyrosine

phosphorylation of the nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1/SRC-3 is

enhanced by Abl kinase and is required for its activity in cancer

cellsMol Cell Biol2865806593200810.1128/MCB.00118-0818765637

|

|

32.

|

C LiYY LiangXH FengSY TsaiMJ TsaiBW

O'MalleyEssential phosphatases and a phospho-degron are critical

for regulation of SRC-3/AIB1 coactivator function and turnoverMol

Cell31835849200810.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.01918922467

|

|

33.

|

P YiQ FengL AmazitDM LonardSY TsaiMJ

TsaiBW O'MalleyAtypical protein kinase C regulates dual pathways

for degradation of the oncogenic coactivator SRC-3/AIB1Mol

Cell29465476200810.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.03018313384

|

|

34.

|

C LiJ AoJ FuDF LeeJ XuD LonardBW

O'MalleyTumor-suppressor role for the SPOP ubiquitin ligase in

signal-dependent proteolysis of the oncogenic co-activator

SRC-3/AIB1Oncogene3043504364201110.1038/onc.2011.15121577200

|

|

35.

|

H WuL SunY ZhangY ChenB ShiR LiY WangJ

LiangD FanG WuCoordinated regulation of AIB1 transcriptional

activity by sumolylation and phosphorylationJ Biol

Chem2812184821856200610.1074/jbc.M60377220016760465

|

|

36.

|

S LiC YangY HongH BiF ZhaoY LiuX AoP PangX

XingAK ChangThe transcriptional activity of co-activator AIB1 is

regulated by the SUMO E3 Ligase PIAS1Biol

Cell104287296201210.1111/boc.20110011622283414

|

|

37.

|

P LabhartS KarmakarEM SalicruBS EganV

AlexiadisBW O'MalleyCL SmithIdentification of target genes in

breast cancer cells directly regulated by the SRC-3/AIB1

coactivatorProc Natl Acad Sci

USA10213391344200510.1073/pnas.040957810215677324

|

|

38.

|

S LiY ShangRegulation of SRC family

coactivators by post-translational modificationsCell

Signal1911011112200710.1016/j.cellsig.2007.02.00217368849

|

|

39.

|

S BautistaH VallèsRL WalkerS AnzickR

ZeillingerP MeltzerC TheilletIn breast cancer, amplification of the

steroid receptor coactivator gene AIB1 is correlated with estrogen

and progesterone receptor positivityClin Cancer

Res42925292919989865902

|

|

40.

|

M GlaeserT FloetottoB HansteinMW BeckmannD

NiederacherGene amplification and expression of the steroid

receptor coactivator SRC3 (AIB1) in sporadic breast and endometrial

carcinomasHorm Metab

Res33121126200110.1055/s-2001-1493811355743

|

|

41.

|

HJ ListR ReiterB SinghA WellsteinAT

RiegelExpression of the nuclear coactivator AIB1 in normal and

malignant breast tissueBreast Cancer Res

Treat682128200110.1023/A:101791092439011678305

|

|

42.

|

C ZhaoK YasuiCJ LeeH KuriokaY HosokawaT

OkaJ InazawaElevated expression levels of NCOA3, TOP1, and TFAP2C

in breast tumors as predictors of poor

prognosisCancer981823200310.1002/cncr.1148212833450

|

|

43.

|

L QinL LiaoA RedmondL YoungY YuanH ChenBW

O'MalleyJ XuThe AIB1 oncogene promotes breast cancer metastasis by

activation of PEA3-mediated matrix metallopteinase 2 (MMP2) and

MMP9 expressionMol Cell

Biol2859375950200810.1128/MCB.00579-0818644862

|

|

44.

|

T KirkegaardLM McGlynnFM CampbellS

MüllerSM ToveyB DunneKV NielsenTG CookeJM BartlettAmplified in

breast cancer 1 in human epidermal growth factor receptor-positive

tumors of tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patientsClin Cancer

Res1314051411200710.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1933

|

|

45.

|

T BourasMC SoutheyDJ VenterOverexpression

of the steroid receptor coactivator AIB1 in breast cancer

correlates with the absence of estrogen and progesterone receptors

and positivity for p53 and HER2/neuCancer

Res61903907200111221879

|

|

46.

|

K LeeA LeeBJ SongCS KangExpression of AIB1

protein as a prognostic factor in breast cancerWorld J Sur

Oncol9139201110.1186/1477-7819-9-13922035181

|

|

47.

|

VJ GnanapragasamHY LeungAS PulimoodDE

NealCN RobsonExpression of RAC 3, a steroid hormone receptor

co-activator in prostate cancerBr J

Cancer8519281936200110.1054/bjoc.2001.217911747336

|

|

48.

|

T BarkhemS NilssonJA GustafssonMolecular

mechanisms, physiological consequences and pharmacological

implications of estrogen receptor actionAm J

Pharmacogenomics41928200410.2165/00129785-200404010-00003

|

|

49.

|

HJ ListKJ LauritsenR ReiterC PowersA

WellsteinAT RiegelRibozyme targeting demonstrates that the nuclear

receptor coactivator AIB1 is a rate-limiting factor for

estrogen-dependent growth of human MCF-7 breast cancer cellsJ Biol

Chem2762376323768200110.1074/jbc.M102397200

|

|

50.

|

S KarmakarEA FosterCL SmithUnique roles of

p160 coactivators for regulation of breast cancer cell

proliferation and estrogen receptor-alpha transcriptional

activityEndocrinology15015881596200910.1210/en.2008-1001

|

|

51.

|

S KarmakarT GaoMC PaceS OesterreichCL

SmithCooperative activation of cyclin D1 and progesterone receptor

gene expression by the SRC-3 coactivator and SMRT corepressorMol

Endocrinol2411871202201010.1210/me.2009-048020392877

|

|

52.

|

MP FereshtehMT TilliSE KimJ XuBW O'MalleyA

WellsteinPA FurthAT RiegelThe nuclear receptor coactivator

amplified in breast cancer-1 is required for Neu (ErbB2/HER2)

activation, signaling, and mammary tumorigenesis in miceCancer

Res6836973706200810.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-670218483252

|

|

53.

|

S AlknerPO BendahlD GrabauK LövgrenO StålL

RydénM FernöSwedish and South-East Swedish Breast Cancer GroupsAIB1

is a predictive factor for tamoxifen response in premenopausal

womenAnn Oncol21238244201010.1093/annonc/mdp29319628566

|

|

54.

|

Q SuS HuH GaoR MaQ YangZ PanT WangF LiRole

of AIB1 for tamoxifen resistance in estrogen receptor-positive

breast cancer

cellsOncology75159168200810.1159/00015926718827493

|

|

55.

|

S MassarwehCK OsborneCJ CreightonL QinA

TsimelzonS HuangH WeissM RimawiR SchiffTamoxifen resistance in

breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with

repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic functionCancer

Res68826833200810.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-270718245484

|

|

56.

|

S KarmakarEA FosterJK BlackmoreCL

SmithDistinctive functions of p160 steroid receptor coactivators in

proliferation of an estrogen-independent, tamoxifen-resistant

breast cancer cell lineEndocr Relat

Cancer18113127201110.1677/ERC-09-028521059860

|

|

57.

|

CK OsborneJ ShouS MassarwehR

SchiffCrosstalk between estrogen receptor and growth factor

receptor pathways as a cause for endocrine therapy resistance in

breast cancerClin Cancer Res11865s870s200515701879

|

|

58.

|

G ArpinoL WiechmannCK OsborneR

SchiffCrosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine

kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical

implications for endocrine therapy resistanceEndocr

Rev29217233200810.1210/er.2006-0045

|

|

59.

|

R ReiterAS OhA WellsteinAT RiegelImpact of

the nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 isoform AIB1-Delta3 on

estrogenic ligands with different intrinsic

activityOncogene23403409200410.1038/sj.onc.120720214691461

|

|

60.

|

RB LanzY BulynkoA MalovannayaP LabhartL

WangW LiJ QinM HarperBW O'MalleyGlobal characterization of

transcriptional impact of the SRC-3 coregulatorMol

Endocrinol24859872201010.1210/me.2009-049920181721

|

|

61.

|

MI Torres-ArzayusJ ZhaoR BronsonM

BrownEstrogen-dependent and estrogen-independent mechanisms

contribute to AIB1-mediated tumor formationCancer

Res7041024111201010.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-408020442283

|

|

62.

|

CM SilvaMA ShupnikIntegration of steroid

and growth factor pathways in breast cancer: focus on signal

transducers and activators of transcription and their potential

role in resistanceMol

Endocrinol2114991512200710.1210/me.2007-010917456797

|

|

63.

|

A OhHJ ListR ReiterA ManiY ZhangE GehanA

WellsteinAT RiegelThe nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 mediates

insulin-like growth factor I-induced phenotypic changes in human

breast cancer cellsCancer

Res6482998308200410.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-035415548698

|

|

64.

|

J YanCT YuM OzenM IttmannSY TsaiMJ

TsaiSteroid receptor coactivator-3 and activator protein-1

coordinately regulate the transcription of components of the

insulin-like growth factor/AKT signaling pathwayCancer

Res661103911046200610.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-244217108143

|

|

65.

|

L LiaoX ChenS WangAF ParlowJ XuSteroid

receptor coactivator 3 maintains circulating insulin-like growth

factor (IGF-I) by controlling IGF-binding protein 3 expressionMol

Cell Biol2824602469200810.1128/MCB.01163-0718212051

|

|

66.

|

MI Torres-ArzayusJ YuanJL DellaGattaH

LaneAL KungM BrownTargeting the AIB1 oncogene through mammalian

target of rapamycin inhibition in the mammary glandCancer

Res661138111388200610.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-231617145884

|

|

67.

|

KM HardyBW BoothMJ HendrixDS SalomonL

StrizziErbB/EGF signaling and EMT in mammary development and breast

cancerJ Mammary Gland Biol

Neoplasia15191199201010.1007/s10911-010-9172-220369376

|

|

68.

|

T LahusenM FereshtehA OhA WellsteinAT

RiegelEpidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and

signaling controlled by a nuclear receptor coactivator, amplified

in breast cancer 1Cancer

Res6772567265200710.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1013

|

|

69.

|

W LongP YiL AmazitHL LaMarcaF AshcroftR

KumarMA ManciniSY TsaiMJ TsaiBW O'MalleySRC-3Delta4 mediates the

interaction of EGFR with FAK to promote cell migrationMol

Cell37321332201010.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.00420159552

|

|

70.

|

GP ColoRR RosatoS GrantMA CostasRAC3

down-regulation sensitizes human chronic myeloid leukemia cells to

TRAIL-induced apoptosisFEBS

Lett58150755081200710.1016/j.febslet.2007.09.05217927986

|

|

71.

|

GP ColoMF RubioIM NojekSE WerbajhPC

EcheverríaCV AlvaradoVE NahmodMD GalignianaMA CostasThe p160

nuclear receptor co-activator RAC3 exerts an anti-apoptotic role

through a cytoplasmatic

actionOncogene2724302444200810.1038/sj.onc.121090017968310

|

|

72.

|

J FerragudA Avivar-ValderasA PlaJ De Las

RivasJF de MoraTranscriptional repression of the tumor suppressor

DRO1 by AIB1FEBS

Lett58530413046201110.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.02521871888

|

|

73.

|

K AokiYJ SunS AokiK WadaE WadaCloning,

expression, and mapping of a gene that is upregulated in adipose

tissue of mice deficient in bombesin receptor subtype-3Biochem

Biophys Res Commun29012821288200210.1006/bbrc.2002.633711812002

|

|

74.

|

GT BommerC JägerEM DürrS BaehsST

EichhorstT BrabletzG HuT FröhlichG ArnoldDC KressDRO1, a gene

down-regulated by oncogenes, mediates growth inhibition in colon

and pancreatic cancer cellsJ Biol

Chem28079627975200510.1074/jbc.M41259320015563452

|

|

75.

|

F TremblayT RevettC HuardY ZhangJF TobinRV

MartinezRE GimenoBidirectional modulation of adipogenesis by the

secreted protein Ccdc80/DRO1/URBJ Biol

Chem28481368147200910.1074/jbc.M80953520019141617

|

|

76.

|

D CorkeryG ThillainadesanN CoughlanRD

MohanM IsovicM TiniJ TorchiaRegulation of the BRCA1 gene by an

SRC3/53BP1 complexBMC

Biochem1250201110.1186/1471-2091-12-5021914189

|

|

77.

|

CK OsborneR SchiffMechanisms of endocrine

resistance in breast cancerAnnu Rev

Med62233247201110.1146/annurev-med-070909-18291720887199

|