Introduction

The typical characteristics of pancreatic

adenocarcinoma are its early local recurrence, systemic

dissemination and poor response to chemotherapy and/or

radiotherapy, thus rendering a poor prognosis with currently used

treatment methods. The lack of traditional therapeutic options has

motivated the search for novel immunotherapeutic approaches to

pancreatic cancer, including cellular immunotherapy (1,2). At

present, despite the development of chemotherapy drugs, research

concerned with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma has only made

modest progress, and the prognosis of advanced pancreatic

adenocarcinoma remains extremely poor (3–5).

Gemcitabine-based regimens are typically offered as standard

approaches of care, and the majority of patients succumb within 6

months (6). The majority of elderly

patients who undergo surgical resection are not able to tolerate

the side-effects of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy following

disease relapse. Celluar immunotherapy has become the fourth

treatment method for malignant tumors (7–10),

which may be a promising approach for these patients.

Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells are considered to be antitumor

effector cells that are capable of rapid proliferation in

vitro, with stronger antitumor activity and a broader spectrum

of tumor targets than other described antitumor effector cells

(10). Moreover, CIK cells are able

to regulate and generally enhance immune function in cancer

patients (11). There are limited

data concerning adoptive immunotherapy in pancreatic

adenocarcinoma. In the present study, we describe a patient with

advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma, who experienced a longer

progression-free survival time (PFS) of >19 months, following

administration of CIK cell immunotherapy. The study was approved by

the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Case report

A 77-year-old female was admitted to Henan Cancer

Hospital, China, with intermittent abdominal pain for one month.

Following investigation, pancreatic cancer was suspected by the

surgeons. On October 14, 2010, the patient underwent resection of

the pancreatic body and tail and the spleen. Analysis of the

pancreatic mass revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma,

including squamous cell carcinoma differentiation, and the

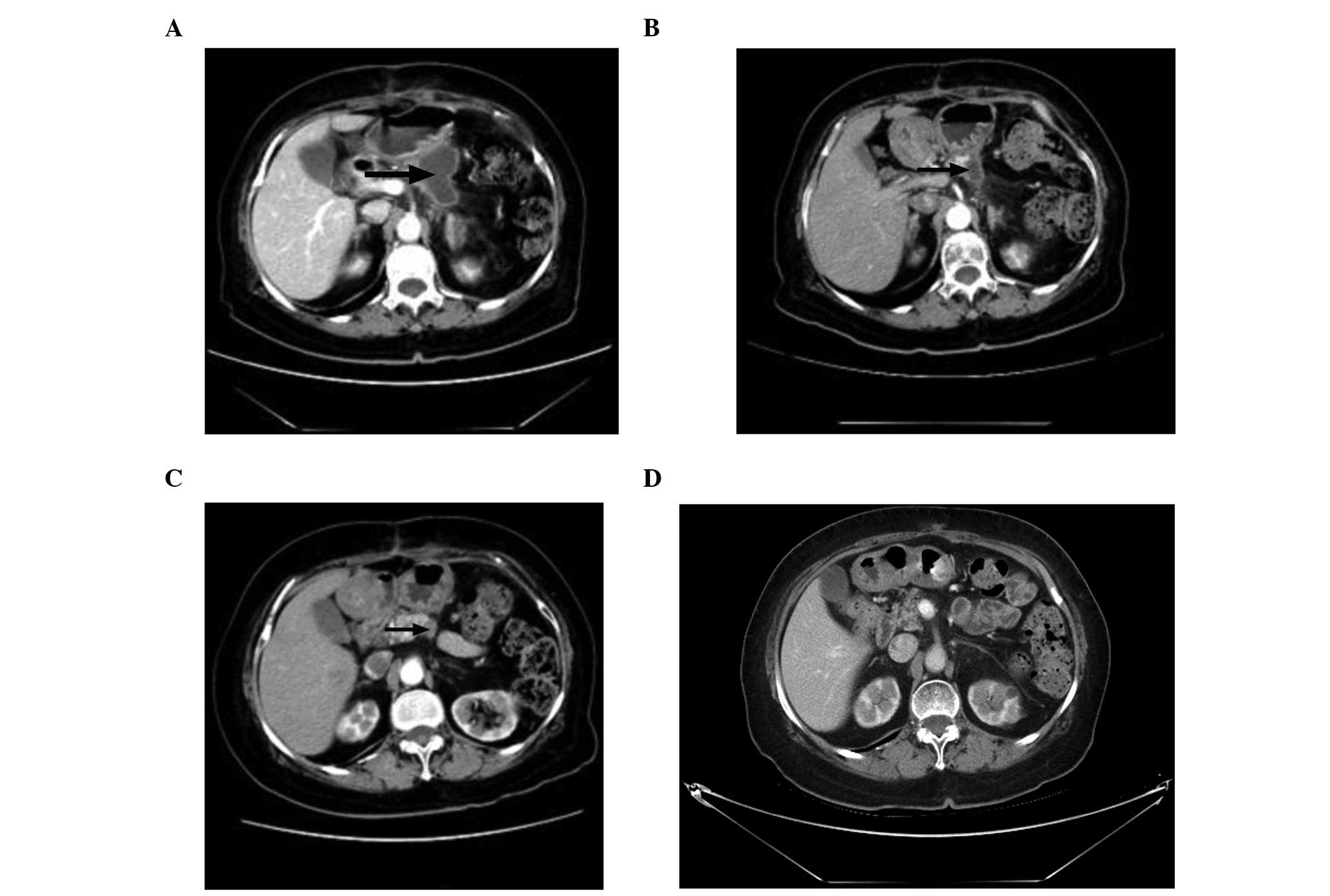

bilateral margins were positive. Abdominal contrast-enhanced

computed tomography (CT) reexamination after one month revealed

that a low-density nodule had emerged at the resection margin

(Fig. 1A). Cancer- and

tissue-specific markers tested, including carbohydrate antigen-199

(CA-199), carbohydrate antigen-724 (CA-724) and carcinoembryonic

antigen (CEA), were observed to be elevated. Notably, the CA-199

level had risen to 1,000 U/ml (reference range, 0–35 U/ml).

Considering that the patient demonstrated poor health and low

Karnofsky performance status (KPS) scores (50 scores), as well as

being unable to tolerate the side-effects of chemotherapy and/or

radiotherapy, CIK cell immunotherapy was administered. Mononuclear

cells were collected from the patient’s 50 ml peripheral blood and

cultured in GT-T551 medium containing anti-CD3 antibody,

recombinant human interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ),

at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, recombinant

human IL-2 (rhIL-2) was added to the medium. The medium was

replaced by fresh IL-2- and IFN-γ-containing medium every 5 days.

At day 10, CIK cells were harvested and their phenotypes were

analyzed. All products were free of bacterial, mycoplasma and

fungal contamination. The endotoxin level was <5 EU. Phenotypic

analysis of autologous CIK cells in the patient prior to culture

and following 10 days of cultivation demonstrated that the

percentages of CD3+, CD3+CD4+,

CD3+CD8+, CD3+CD56+ and

CD25+ cell subsets increased from 45.40±5.21,

29.08±4.86, 18.80±5.45, 3.77±1.665 and 12.51±4.01% to 90.06±9.22,

44.50±8.18, 38.40±4.19, 15.21±4.53 and 31.75±5.87%, respectively

(P<0.01). However, the percentages of

CD3+/16+/56+, CD14+ and

CD20+ cell subsets decreased from 14.73±3.54, 16.46±6.06

and 11.19±3.18% to 6.78±1.91, 5.87±2.09 and 7.84±2.53%,

respectively (P<0.05). The total number of CIK cells in one

cycle is ∼ 5×109. From November 10, 2010 to June 27,

2011, the patient recieved 4 cycles of CIK cell immunotherapy and 2

million units of IL-2 from day 1–5 per infusion of CIK cells. In

the period of CIK cell therapy, no adverse reactions were observed.

Following 4 cycles of CIK cell immunotherapy, the abdominal

contrast-enhanced CT reexamination demonstrated that the

low-density nodule reduced significantly (Fig. 1B). The cancer- and tissue-specific

markers (CA-199, CA-724 and CEA) returned to their normal levels.

The patient then received another 12 cycles of CIK cell

immunotherapy. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT examination indicated

that the low-density nodule had slightly decreased (Fig. 1C) compared with the result

demonstrated in Fig. 1B. The

cancer- and tissue-specific marker levels (CA-199, CA-724 and CEA)

remained at their normal levels. Following 16 cycles of CIK cell

immunotherapy, it was recommended that the patient undergo

abdominal contrast-enhanced CT examination every 3 months. The

abdominal CT scan on February 29, 2012 demonstrated that the

low-density nodule had almost disappeared (Fig. 1D). From March 7, 2012 to April 29,

2012, the patient received a further 4 cycles of CIK cell infusion

to ensure treatment efficacy. However, on May 28, 2012, the

abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed that the low-density

nodule had emerged in the same place as previously, and the CA-199

level had elevated to 1,000 U/ml once more. At present, the

progression-free survival time (PFS) of the patient is >19

months and the patient has not succumbed. During immunotherapy, the

patient had a good quality of life and their KPS score increased

from 50 to 80.

Discussion

In the field of oncology, pancreatic cancer remains

a fatal disease with a poor prognosis, thus presenting a challenge

for oncologists (12,13). In patients with advanced pancreatic

cancer, the mean overall survival time is <6 months (6). Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are the

most common approaches for treating locally relapsed and metastatic

pancreatic cancer (14); however,

the overall survival time is only modestly prolonged. Additionally,

adverse reactions to chemotherapy/radiotherapy may be not tolerable

in elderly patients. However, the lack of conventional therapeutic

options is also important in motivating the search for novel

therapeutic approaches to pancreatic cancer. In the present case,

the patient was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer, and had

a poor prognosis following surgery. Additionally, the patient was

not able to tolerate the side-effects of traditional chemotherapy

and radiotherapy. Subsequently, CIK cell immunotherapy alone was

administered to the patient, achieving a beneficial effect.

Presently, immunotherapy has become the fourth

treatment modality for malignant tumors, and may be a promising

approach for pancreatic cancer (7–10).

Certain studies have demonstrated that CIK cells are heterogeneous

cell populations that express CD3 and CD56 as well as the

activation receptor of NK cells (NKG2D), antigen, and possess

MHC-unrestricted cytotoxicity toward pancreatic cancer but not

toward normal targets (15,16). CIK cells are considered to be a type

of antitumor effector cells, and proliferate rapidly in

vitro, with stronger antitumor activity in a broad spectrum of

tumors (9,17). In addition, CIK cells regulate and

enhance cellular immune functions in patients with pancreatic

cancer by secretion of cytokines, such as interferon-γ, and a

number of chemokines, including RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β (18,19).

The application of CIK cells as adoptive immunotherapy is important

in cancer treatment. The application of CIK cells as adoptive

immunotherapy in solid tumor treatment has been frequently reported

in the literature (10,20). In particular, Liu et al

applied CIK cells to treat 74 cases of metastatic renal cell

carcinoma patients in a randomized stage III clinical trial. The

mean PFS was prolonged by 4 months and the mean overall survival

time (mOS) was prolonged by 27 months compared with the control arm

(10). Shi et al applied CIK

cells to treat locally advanced gastric cancer patients and

indicated that adjuvant immunotherapy with CIK cells prolonged

disease-free survival (DFS) and significantly improved the mOS

(21). However, there are few data

concerned with applying CIK cells to treat pancreatic cancer in

clinical practice. The present case provides a novel treatment

option and further clinical practices are required to verify its

efficacy.

In conclusion, we describe the case of a 77-year old

female with pancreatic cancer who underwent surgery, although the

bilateral margins were positive. After one month, imaging

examination revealed that a low-density nodule had emerged at the

resection margin. Considering the patient’s poor condition, low KPS

scores and inability to tolerate the side-effects of chemotherapy

and/or radiotherapy, the patient was treated with CIK cell

immunotherapy. The patient achieved a PFS of >19 months, which

was longer than that demonstrated by using chemotherapy and/or

radiotherapy. In conclusion, CIK immunotherapy may be an effective

treatment method for advanced pancreatic cancer, particularly for

elderly patients.

References

|

1

|

Laheru D and Jaffee EM: Immunotherapy for

pancreatic cancer - science driving clinical progress. Nat Rev

Cancer. 5:459–467. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Vizio B, Novarino A, Giacobino A, et al:

Potential plasticity of T regulatory cells in pancreatic carcinoma

in relation to disease progression and outcome. Exp Ther Med.

4:70–78. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Franssen B and Chan C: Pancreatic Cancer:

The surgeons point of view. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 76:353–361.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Janes RJ, Niederhuber JE, Chmiel JS, et

al: National patterns of care for pancreatic cancer. Results of a

survey by the Commission on Cancer. Ann Surg. 223:261–272. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Moss RA and Lee C: Current and emerging

therapies for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Onco Targets

Ther. 3:111–127. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Koido S, Homma S, Takahara A, et al:

Current immunotherapeutic approaches in pancreatic cancer. Clin Dev

Immunol. 2011:2675392011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dougan M and Dranoff G: Immune therapy for

cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 27:83–117. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hontscha C, Borck Y, Zhou H, et al:

Clinical trials on CIK cells: first report of the international

registry on CIK cells (IRCC). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 137:305–310.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Schwaab T, Schwarzer A, Wolf B, et al:

Clinical and immunologic effects of intranodal autologous tumor

lysate-dendritic cell vaccine with Aldesleukin (Interleukin 2) and

IFN-{alpha}2a therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients.

Clin Cancer Res. 15:4986–4992. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu L, Zhang W, Qi X, et al: Randomized

study of autologous cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in

metastatic renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 18:1751–1759. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Schmidt-Wolf IG, Lefterova P, Mehta BA, et

al: Phenotypic characterization and identification of effector

cells involved in tumor cell recognition of cytokine-induced killer

cells. Exp Hematol. 21:1673–1679. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Werner J and Buchler MW: management of

pancreatic cancer: recent advances. Dtsch Med Wochenschr.

136:1807–1810. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ng J, Zhang C, Gidea-Addeo D, et al:

Locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: update and progress.

JOP. 13:155–158. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cardenes HR, Chiorean EG, Dewitt J, et al:

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer: current therapeutic approach.

Oncologist. 11:612–623. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Karimi M, Cao TM, Baker JA, et al:

Silencing human NKG2D, DAP10, and DAP12 reduces cytotoxicity of

activated CD8+ T cells and NK cells. J Immunol. 175:7819–7828.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Verneris MR, Karami M, Baker J, et al:

Role of NKG2D signaling in the cytotoxicity of activated and

expanded CD8+ T cells. Blood. 103:3065–3072. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li R, Wang C, Liu L, et al: Autologous

cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in lung cancer: a phase

II clinical study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 61:2125–2133. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Schmidt-Wolf IG, Lefterova P, Mehta BA, et

al: Phenotypic characterization and identification of effector

cells involved in tumor cell recognition of cytokine-induced killer

cells. Exp Hematol. 21:1673–1679. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Joshi PS, Liu JQ, Wang Y, et al:

Cytokine-induced killer T cells kill immature dendritic cells by

tcr-independent and perforin-dependent mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol.

80:1345–1353. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mesiano G, Todorovic M, Gammaitoni L, et

al: Cytokine-induced killer (cik) cells as feasible and effective

adoptive immunotherapy for the treatment of solid tumors. Expert

Opin Biol Ther. 12:673–684. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shi L, Zhou Q, Wu J, et al: Efficacy of

adjuvant immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells in

patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 61:2251–2259. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|