Introduction

There are five types of germ cell tumours according

to clinical presentation, pathology and cytogenetics. Type I

tumours (teratomas and yolk sac tumours) are more frequent in

extragonadal sites than in the gonads; whereas type II tumours

(seminomas and non-seminomas) occur mainly in the gonads (1) Primary urinary bladder germ cell

tumours are exceedingly rare. The current report presents a case of

primary yolk sac tumour of the urinary bladder in a 31-year-old

female ex-ketamine abuser. The diagnosis of a yolk sac tumour at

this rare site can be difficult and biopsy alone is not reliable.

No previous studies have reported a correlation between chronic

ketamine abuse and urinary bladder malignancy development. Informed

consent was obtained from the patient.

Case report

In 2007, a 26-year-old female presented to the

Department of Urology of the Tuen Mun Hospital (Hong Kong, China)

with bilateral hydronephrosis. Since 2000, the patient had been

consuming 8–10 ketamine tablets daily from illicit sources.

Cystoscopy revealed cystitis and a biopsy showed florid reactive

changes in the urinary bladder associated with erosion involving

the urothelium, which underwent extensive intestinal metaplastic

changes. The patient defaulted follow-up examinations.

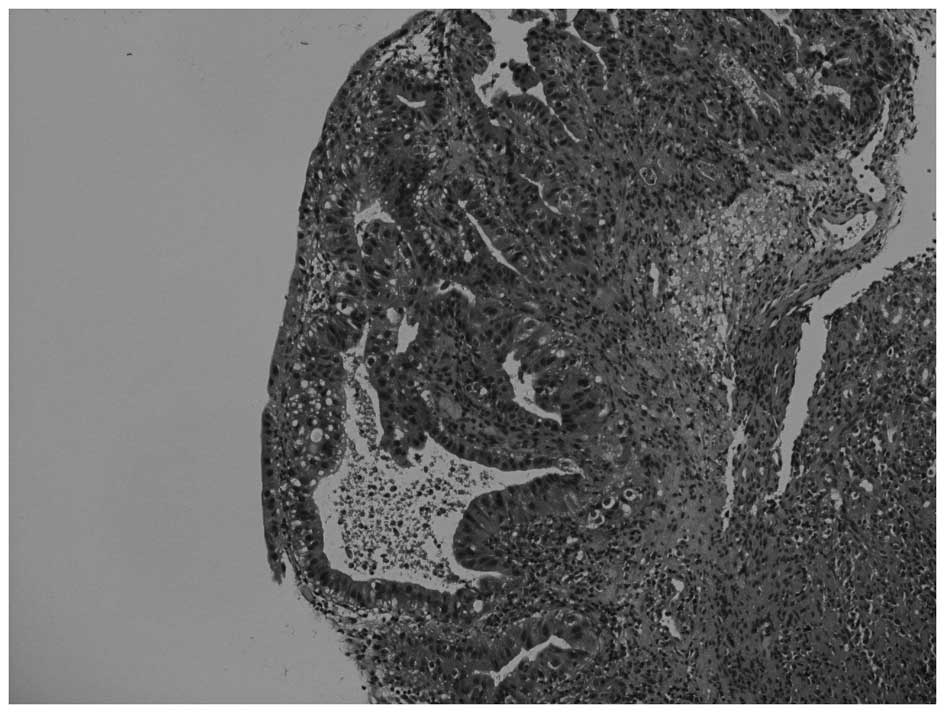

In January 2012, the patient presented again with

gross haematuria. Cystoscopy identified a 4-cm whitish mass at the

dome of the urinary bladder, with pathological features indicative

of adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1). A

computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed on

February 3, 2012, which demonstrated masses within the urinary

bladder (Fig. 2). A transurethral

resection of the bladder tumours was subsequently performed on

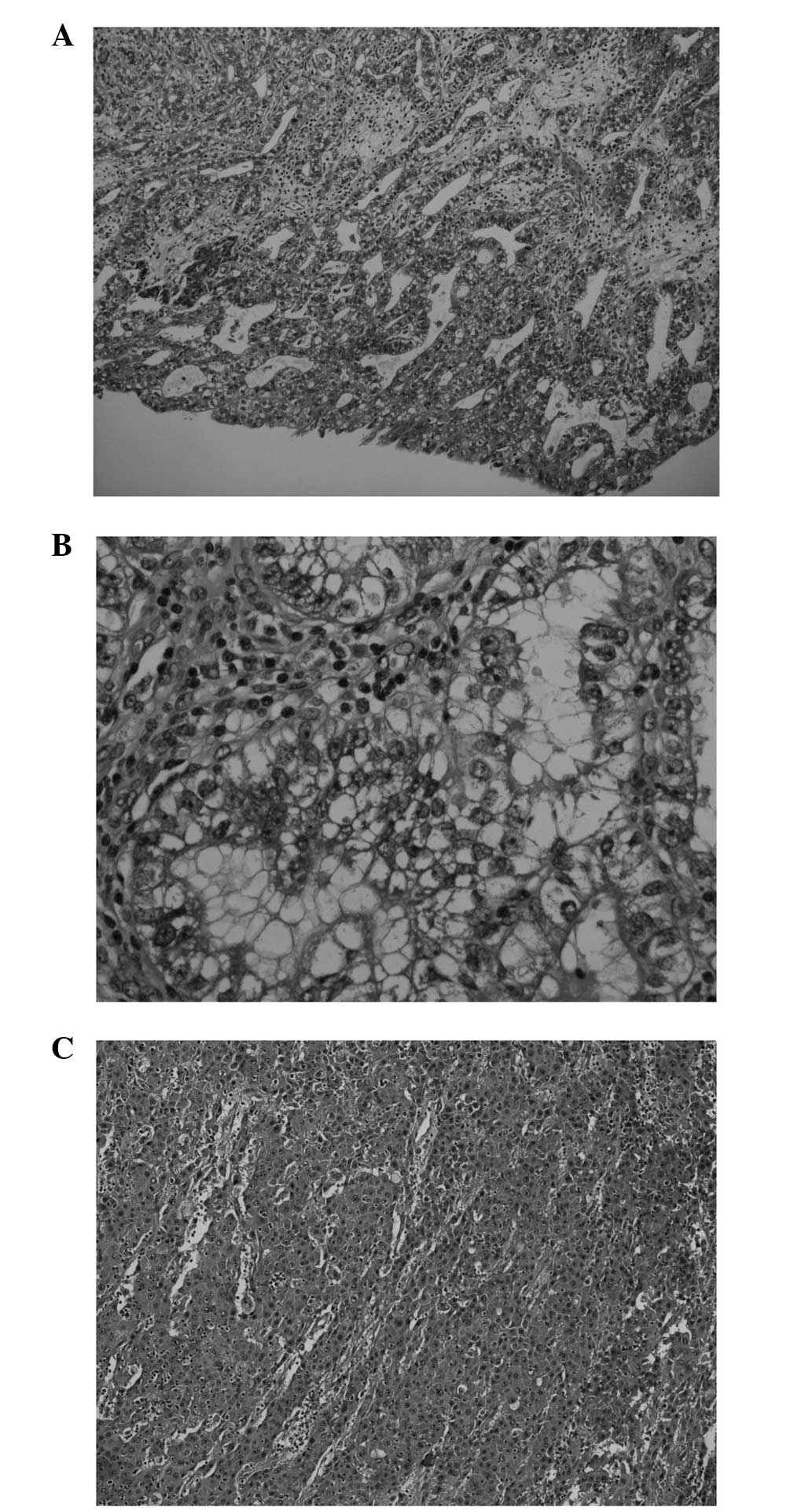

January 31, 2012. Pathological examination showed a

muscle-invasive, poorly-differentiated carcinoma with a clear cell

component. The patient underwent a radical cystectomy and T-pouch

orthotopic substitution cystoplasty on February 21, 2012. Two

similar 5-cm tumours were present, with various histological

morphologies in different areas, featuring reticular, glandular,

papillary, microcystic, solid and hepatoid patterns (Fig. 3). The tumour cells showed

immunohistochemical reactivity for antibodies against MNF116,

α-fetoprotein (αFP) and Sal-like protein 4 (Fig. 4), but not against EMA, HCG,

placental alkaline phosphatase, CD30 and octamer-binding

transcription factor 3/4. The final pathological diagnosis was of a

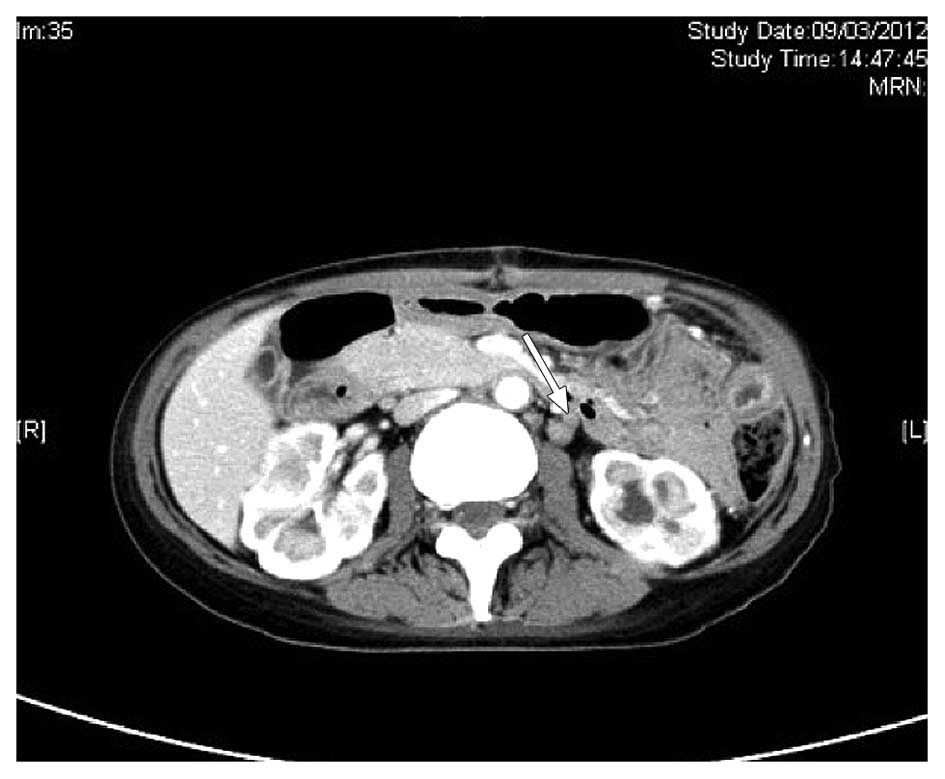

yolk sac tumour. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis on March 9,

2012, demonstrated several enlarged paraaortic lymph nodes of ≤1.5

cm in size (Fig. 5). No sites of

suspicious ovarian primary or other disease involvement were

identified. An examination performed by a gynaecologist did not

reveal a primary gynaecological site of disease.

The serum αFP level was found to be raised (1,028

ng/ml) on March 13, 2012, but fell to 45.9 ng/ml on April 17, 2012,

prior to undergoing chemotherapy. In view of the impaired renal

function (48.9 ml/min creatinine clearance, according to the

Cockcroft-Gault formula), the patient was treated with the

combination chemotherapy JEB regimen (day 1, area under curve 5

mg/ml/min carboplatin, intravenously; days 1–5, 100

mg/m2 etoposide, intravenously; days 1, 8 and 15, 30 mg

bleomycin, intravenously; and the regimen was repeated every 21

days). Two cycles of chemotherapy were administered between April

and May 2012. The first cycle of chemotherapy was complicated by

grade 3 mucositis and neutropenic sepsis. Moreover, the second

cycle was complicated by appendicitis with intra-abdominal abscess

formation requiring laparotomy, intensive care and prolonged

post-operative management. It was then decided to terminate the

chemotherapy. The patient was put on close clinical surveillance,

including regular serum tumour marker analysis and CT scan

monitoring. The final CT scan, on July 23, 2012, showed no interval

change of the paraaortic lymph nodes. The patient’s nadir serum αFP

level following chemotherapy was 14.1 ng/ml on August 9, 2012.

Discussion

Primary germ cell tumours of the urinary bladder are

extremely rare. In the present review of the literature, <10

cases had been previously reported (2–7). To

the best of our knowledge, the current case is the first reported

primary yolk sac tumour of the urinary bladder in adulthood.

The hypotheses for the development of extragonadal

germ cell tumours include the following: i) Failure of the

primitive germ cells to complete the normal migration along the

urogonadal ridges; ii) germ cell tumours undergo reverse migration;

iii) germ cell tumours are the metastatic deposits from occult

gonadal primaries; and iv) germ cell tumours result from the germ

cells distributed to other organs physiologically for function

(1,8,9).

The accurate pathological diagnosis of germ cell

tumours and the distinction from non-germ cell tumours is critical,

as the majority of cases of germ cell tumours are potentially

curable, particularly in young patients. Diagnosing a yolk sac

tumour may be difficult since a yolk sac tumour may assume a

variety of architectural patterns, including microcystic, solid,

myxomatous, papillary, polyvesicular vitelline, alveolar,

glandular, hepatoid and intestinal (10,11).

These may explain the diagnoses of adenocarcinoma and invasive

carcinoma in the present patient’s previous pathological

examinations. The presence of the particularly characteristic

histological Schiller-Duval body, which consists of arrays of

neoplastic cells surrounding a central vessel in a glomeruloid

appearance, aided the diagnosis (12–14).

Beside classical histological features, immunohistochemical study

is essential for determining the correct diagnosis. This is based

on the relatively specific immunohistochemical profiles carried by

the various types of germ cell tumour (Table I) (12,14–18).

| Table IImmunohistochemical study of germ cell

tumours. |

Table I

Immunohistochemical study of germ cell

tumours.

| Type of germ cell

tumour | Reactivity |

|---|

|

Seminoma/dysgerminoma | PLAP, c-kit and

Oct3/4 |

| Spermatocytic

seminoma | c-kit and PLAP |

| Embryonal

carcinoma | MNF116 (cytokeratin),

CD30, Oct3/4 and SALL4 |

| Yolk sac tumour | αFP and SALL4 |

| Choriocarcinoma | MNF116

(cytokeratin) |

The patient’s medical history in 2007 identified a

dysplastic process occurring in the urinary bladder. However, in

the present review of the literature, the correlation between

ketamine abuse and the formation of a urinary bladder malignancy

was shown to have not previously been documented. The chronic

recreational use of ketamine and its associated urinary system

issues has become a global issue (19–21).

The new medical entity ‘ketamine-induced ulcerative cystitis’

originated from a publication by Shahani et al(21) in 2007. Common symptoms include

frequent urination, urge incontinence and painful haematuria. The

method of production and composition of illicit ketamine is

unclear, and the chemicals and metabolites responsible for the

pathogenesis are not well known. Cystoscopic observations may

reveal features of cystitis and ulceration, characterised by

granulation tissue formation and fibrosis in the epithelium and

lamina propria (21). Although

there is eosinophilic infiltration, the overall pathology of

chemical cystitis is distinct from that of eosinophilic cystitis,

which has been reported to be associated with transitional cell

carcinoma (22).

Despite their rarity, extragonadal yolk sac tumours

mainly affect children and young females (9–11,13).

The mediastinum and retroperitoneum are the most common

extraovarian primary sites. Less common sites may include the

omentum, vagina and brain (10–12,17).

These tumours are highly aggressive, harbouring the tendency for

early lymphatic and haematological metastasis to distant sites

(11,17). Long-term survival rates,

specifically for extragonadal yolk sac tumours, are not well known.

The International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group data,

determined the 5-year survival rate for mediastinal non-seminoma

(i.e. poor risk group) as 48% (23), and a large case series from the

German group of extragonadal germ cell tumours showed similar

survival rates (8,24,25).

Extragonadal germ cell tumours have been managed under the same

principle as their primary gonadal counterparts, using treatment

comprised of systemic chemotherapy together with local

treatment, including surgery and radiotherapy. Adjunct

chemotherapy following local surgical treatment is recommended by

the majority of studies if the disease is operable upfront;

cisplatin-based regimens are widely used (8–11,13,24–27).

Regimens, including bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) and

vinblastine, ifosfamide and cisplatin (VIP), are the most commonly

adopted. In addition, high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous

bone marrow transplantation is used (8,24,28).

To date, the evidence has not been sufficient to determine the

optimal chemotherapy duration for extragonadal germ cell tumours,

including yolk sac tumours. Four cycles of cisplatin-based

combination chemotherapy is the most prevalent treatment regime

(8,11,12,24,26,27),

and factors taken into account prior to treatment include patient

age, performance status, organ function (particularly the lungs and

kidneys), histology, serum marker levels, the location of the

primary tumour and the sites of the metastases (23,28,29).

In conclusion, the diagnosis of a yolk sac tumour

may be challenging in sites of rare occurrence. A high level of

clinical suspicion is required, particularly in young patients.

Prior to the availability of new therapeutic agents, systemic

cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains the standard of care for

extragonadal germ cell tumours.

References

|

1

|

Oosterhuis JW, Stoop H, Honecker F and

Looijenga LH: Why human extragonadal germ cell tumours occur in the

midline of the body: old concepts, new perspectives. Int J Androl.

30:256–263. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kuyumcuoğlu U and Kale A: Unusual

presentation of a dermoid cyst that derived from the bladder dome

presenting as subserosal leiomyoma uteri. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol.

35:309–310. 2008.

|

|

3

|

Taylor G, Jordan M, Churchill B and Mancer

K: Yolk sac tumor of the bladder. J Urol. 129:591–594.

1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tinkler SD, Roberts JT, Robinson MC and

Ramsden PD: Primary choriocarcinoma of the urinary bladder: a case

report. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 8:59–61. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fowler AL, Hall E and Rees G:

Choriocarcinoma arising in transitional cell carcinoma of the

bladder. Br J Urol. 70:333–334. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yokoyama S, Hayashida Y, Nagahama J,

Nakayama I, Kashima K and Ogata J: Primary and metaplastic

choriocarcinoma of the bladder. A report of two cases. Acta Cytol.

36:176–182. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Huang HY, Ko SF, Chuang JH, Jeng YM, Sung

MT and Chen WJ: Primary yolk sac tumor of the urachus. Arch Pathol

Lab Med. 126:1106–1109. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bokemeyer C, Hartmann JT, Fossa SD, et al:

Extragonadal germ cell tumors: relation to testicular neoplasia and

management options. APMIS. 111:49–63. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ait Benali H, Lalya L, Allaoui M, et al:

Extragonadal mixed germ cell tumor of the right arm: description of

the first case in the literature. World J Surg Oncol.

10:692012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Furtado LV, Leventaki V, Layfield LJ,

Lowichik A, Muntz HR and Pysher TJ: Yolk sac tumor of the thyroid

gland: a case report. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 14:475–479. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim SW, Park JH, Lim MC, Park JY, Yoo CW

and Park SY: Primary yolk sac tumor of the omentum: a case report

and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 279:189–192.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pasternack T, Shaco-Levy R, Wiznitzer A

and Piura B: Extraovarian pelvic yolk sac tumor: case report and

review of published work. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 34:739–744. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Dede M, Pabuccu R, Yagci G, Yenen MC,

Goktolga U and Gunhan O: Extragonadal yolk sac tumor in pelvic

localization. A case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol.

92:989–991. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Moran CA, Suster S and Koss MN: Primary

germ cell tumors of the mediastinum: III. Yolk sac tumor, embryonal

carcinoma, choriocarcinoma and combined nonteratomatous germ cell

tumors of the mediastinum - a clinicopathologic and

immunohistochemical study of 64 cases. Cancer. 80:699–707. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hoei-Hansen CE, Kraggerud SM, Abeler VM,

Kaern J, Rajpert-De Meyts E and Lothe RA: Ovarian dysgerminomas are

characterised by frequent KIT mutations and abundant expression of

pluripotency markers. Mol Cancer. 6:122007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Cao D, Humphrey PA and Allan RW: SALL4 is

a novel sensitive and specific marker for metastatic germ cell

tumors, with particular utility in detection of metastatic yolk sac

tumors. Cancer. 115:2640–2651. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gupta R, Mathur SR, Arora VK and Sharma

SG: Cytologic features of extragonadal germ cell tumors: a study of

88 cases with aspiration cytology. Cancer. 114:504–511. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang F, Liu A, Peng Y, et al: Diagnostic

utility of SALL4 in extragonadal yolk sac tumors: an

immunohistochemical study of 59 cases with comparison to

placental-like alkaline phosphatase, alpha-fetoprotein and

glypican-3. Am J Surg Pathol. 33:1529–1539. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Venyo A and Benatar B: A Review of the

Literature on Ketamine-Abuse-Uropathy. WebmedCentral Urology.

3:WMC0030482012.

|

|

20

|

Chu PS, Kwok SC, Lam KM, et al: ‘Street

ketamine’-associated bladder dysfunction: a report of ten cases.

Hong Kong Med J. 13:311–313. 2007.

|

|

21

|

Shahani R, Streutker C, Dickson B and

Stewart RJ: Ketamine associated ulcerative cystitis: a new clinical

entity. Urology. 69:810–812. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Itano NM and Malek RS: Eosinophil cystitis

in adults. J Urol. 165:805–807. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

No authors listed. International Germ Cell

Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system

for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer

Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 15:594–603. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bokemeyer C, Nichols CR, Droz JP, et al:

Extragonadal germ cell tumors of the mediastinum and

retroperitoneum: results from an international analysis. J Clin

Oncol. 20:1864–1873. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

De Corti F, Sarnacki S, Pattec C, et al:

Prognosis of malignant sacrococcygeal germ cell tumours according

to their natural history and surgical management. Surg Oncol.

21:e31–e37. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pliarchopoulou K and Pectasides D:

First-line chemotherapy of non-seminomatous germ cell tumors

(NSGCTs). Cancer Treat Rev. 35:563–569. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

de La Motte Rouge T, Pautier P, Duvillard

P, et al: Survival and reproductive function of 52 women treated

with surgery and bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy

for ovarian yolk sac tumor. Ann Oncol. 19:1435–1441.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Riese MJ and Vaughn DJ: Chemotherapy for

patients with poor prognosis germ cell tumors. World J Urol.

27:471–476. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hartmann JT, Nichols CR, Droz JP, et al:

Prognostic variables for response and outcome in patients with

extragonadal germ-cell tumors. Ann Oncol. 13:1017–1028. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|