Introduction

Chondromas and chondrosarcomas of the cranial base

are infrequent neoplastic diseases, with the majority of tumors

occurring in the lateral area of the cranial base on the midline.

Due to the deep location and the invasion to the cranial nerves and

critical vascular structures, total resection of the tumor, a

difficult challenge for neurosurgeons worldwide, is extremely

difficult and is frequently accompanied by various complications

(1). In addition, the majority of

chondromas and chondrosarcomas arise de novo and are common

in patients with Ollier’s disease, Maffucci syndrome, Paget’s

disease and osteochondroma. Several histological subtypes of

chondrosarcoma have been reported, including conventional,

mesenchymal, clear cell and dedifferentiated subtypes (2). Chondromas and chondrosarcomas grow

slowly, but are locally aggressive and prone to relapse (3). To date, few series have analyzed

chondroma and chondrosarcoma and a number of controversies remain

concerning the appropriate treatment modality. The present study

investigated 19 patients who were diagnosed with cranial base

chondromas and chondrosarcomas and surgically treated in the

Neurosurgery Department of Beijing Tiantan Hospital of Capital

Medical University (Beijing, China) between 1998 and 2010.

Neuroradiological examination and surgical treatment data were

collected from the hospital records and reviewed. Patient symptoms,

treatments and outcomes are presented.

Patients and methods

Patient characteristics

The study group consisted of 10 males and 9 females,

with a mean age of symptom onset of 33.6 years (range, 15–57

years). The time from the onset of symptoms to the pathological

diagnoses ranged from 2 months to 12 years. The presenting symptoms

varied amongst the patients. In total, 12 presented with headaches

and dizziness, 13 with double vision and abducens palsy, seven with

poor vision and papilledema, four with facial numbness and paresis,

three with tinnitus and decreased hearing, two with convulsion and

two with hoarseness, decreased gag reflex and tongue atrophy. The

average pre-operative KPS was 87.1 (range 60–90). Patients provided

written informed consent.

Neuroradiological examinations

All patients underwent computed tomography (CT) and

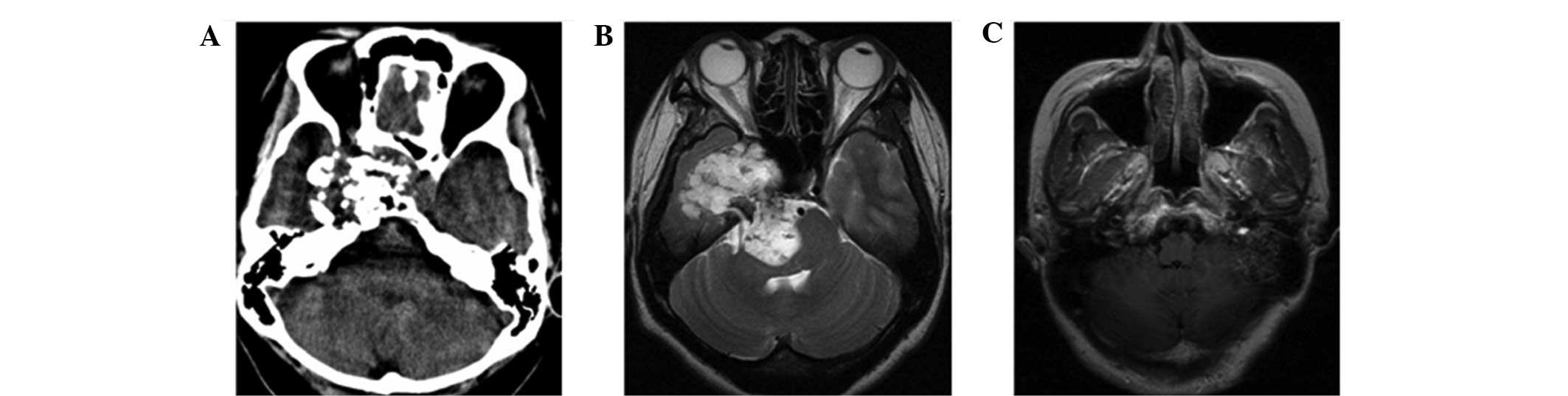

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Of the 19 tumors, 11 were located

in the parasellar region (Fig. 1A),

six extended from the middle cranial fossa to the posterior cranial

fossa (Fig. 1B) and two were

located in the jugular foramen region (Fig. 1C). The mean maximum diameter of the

tumors, as assessed by MRI, was 4.9 cm (range, 3.1–8.3 cm). In

three patients, cerebral angiography was carried out and the tumors

showed no or mild staining.

Surgical treatments

All 19 patients underwent surgical procedures. The

frontotemporal or preauricular subtemporal-infratemporal approach

was used for the tumors located in the parasellar region in 11

cases, the tempo-occipital transtentorial or presigmoid

supratentorial-infratentorial approach was used for the lesions

involving the middle cranial fossa and the posterior cranial fossa

was employed in another six cases, and the far-lateral or

retrosigmoid approach was applied for the lesions located in the

jugular foramen region in two cases.

Results

Surgical findings

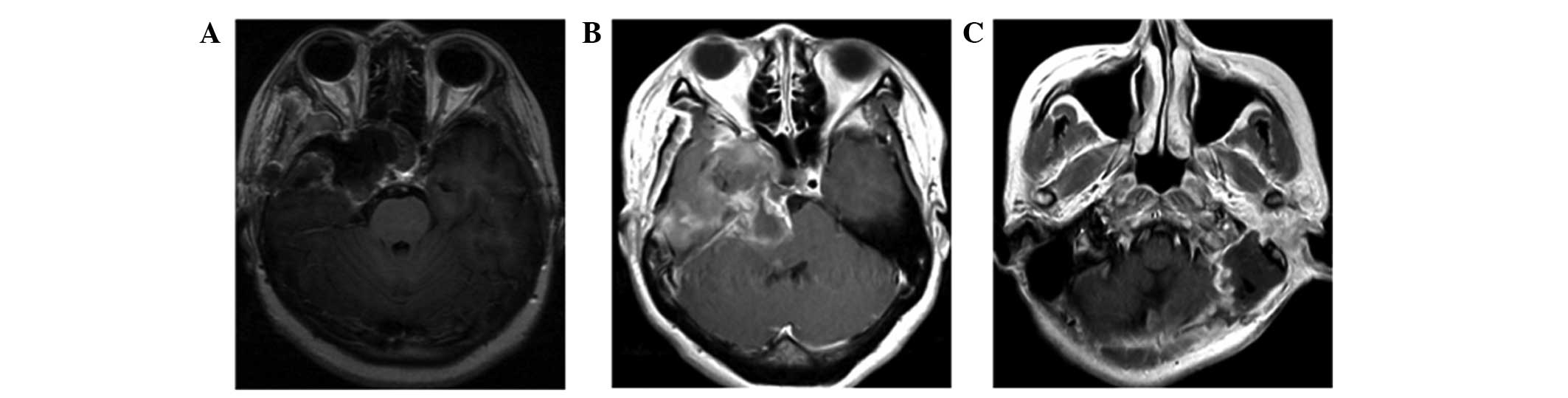

Of the 19 patients, 13 underwent a total or

near-total resection (Fig. 2A–C),

five underwent a subtotal resection and one underwent a partial

resection. Post-operatively, new cranial nerve disorders were the

most frequent complications, including six cases of oculomotor

nerve palsies and two disorders of cranial nerves VII and VIII. In

addition, two patients suffered cerebrospinal fluid leakage, with

recovery following lumbar drainage, and one patient suffered a

post-operative brain infarct, with recovery following anti-ischemic

treatment. There were no post-operative fatalities.

Imaging findings

CT scans showed the tumors as mass lesions with high

and equal density mixed areas and well-defined boundaries. The

lesions were poorly-enhanced heterogeneously following contrast

enhancement, and speckled calcification and bony erosion was shown

clearly on bone-window scans. Upon MRI, the lesions were shown as a

hypointensity on T1-weighted scans and a mixed hyper- and

hypointensity on T2-weighted scans. In certain cases, the tumors

pressed or encased the internal carotid artery (ICA), and also

thinned and occluded the ICA entering the cavernous sinus. In

addition, the lesions displaced the surrounding brain tissues, but

no cerebral edemas were observed.

Pathological diagnoses

Histological analyses were performed in all cases,

and diagnoses of chondromas were confirmed in 14 patients and

chondrosarcomas in five. Additionally, immunohistochemical analyses

were performed in seven cases, and the tumors were negative for

epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and cytokeratin (CK) and positive

for S100.

Follow-up

A total of 15 patients were followed up for a mean

interval of 67.2 months (range, 5–140 months). Two patients

experienced recurrence and have been monitored up to the present

day. A complete or partial recovery was recorded in four patients

with oculomotor nerve palsies, two with poor vision, six with

abducens palsy, three with facial and acoustic nerve disorders and

two with hoarseness. No patients underwent radiotherapy. Following

surgery, the average KPS was 78.7. Among the 17 patients who were

followed up, 13 (76.5%) had a normal life (KPS, 80–90) in society,

three (17.6%) had moderate disabilities (KPS, 60–70) and one (5.9%)

had severe disabilities (KPS, 50).

Discussion

Chondrosarcomas and chondromas of the cranial base

are rare tumors whose derivation is indicated to be from the

remnants of embryonic cartilage tissue in the cartilaginous

junction of cranial base sutures, or from chondrocytes in the areas

of residual enchondral cartilage (1,4–7). In

the present study, the mean age of occurrence ranged from the third

to fourth decade of life, with no gender preference observed.

Cranial base chondromas and chondrosarcomas usually arise in the

central area of ossification or the suture, including the

sphenopetrosal, sphenoclival or petroclival junctions, and most

frequently are located in the parasellar area of the middle cranial

base, extradurally. Additionally, these tumors frequently invade

the cavernous sinus and extend into the posterior cranial fossa.

The lesions develop and invade cranial nerves and major blood

vessels gradually due to the slow growth of the tumors, thus

accounting for the long duration of the symptoms. The most frequent

clinical presentations are deficits of the cranial nerves,

including the abducent, optic, acoustic-facial and lower cranial

nerves, and chronically increased intracranial pressures and

epilepsies (8,9).

Chondromas are recognized as a dyschondroplasia

caused by developmental errors in enchondral ossification. Notably,

Ollier’s disease and Maffucci’s syndrome are also characterized by

dyschondroplasia. Ollier’s disease is referred to as a multiple

enchondromatosis without dysplasia of other tissues or organs

(10,11). Maffucci’s syndrome is a

non-hereditary mesoblastic dysplasia and is characterized by the

presence of multiple enchondromas and cutaneous and/or other

parenchymatous hemangiomas (12–15).

Although Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s syndrome associated with

intracranial neoplasms are extremely rare, cranial base chondromas

or chondrosarcomas are believed to be a partial representation of

the two diseases (10,14–16).

In the present study, two patients were diagnosed with Maffucci’s

syndrome associated with a cranial base chondrosarcoma.

Using neuroradiology, intracranial chondromas or

chondrosarcomas are commonly imaged as a mass lesion located in the

extradural lateral-middle areas of the cranial base, and

particularly present as a single lesion in the parasellar region

(1). The lesion can extend from the

middle cranial fossa to the posterior cranial fossa, and can be

imaged as a dumbbell profile. The lesion invading the jugular

foramen can result in the widening of this foramen (5). As presented in the current study, the

tumors normally arise in skeletal structures and are frequently

accompanied by calcification and ossification. CT scans can reveal

these characteristics well, and thus may be more useful than MRI

for the presumptive diagnoses. By contrast, compared with CT, MRI

is better for revealing the associations between lesions and

surrounding anatomical structures, particularly those involving the

ICA. According to the presenting symptoms and signs, and the

neuroradiological examinations, a pre-operative diagnosis of

chondroma or chondrosarcoma can be presumed.

Chondrosarcomas and chondromas can and should be

distinguished from chordomas (17,18).

Chordomas arise from the remnants of the primitive notochord and

are commonly located in the middle line of the clivus, where the

bone may be observably eroded and even completely replaced by the

tumor tissues. Chondrosarcoma and chondromas are occasionally

difficult to differentiate from chordomas morphologically. In such

cases, an immunohistochemical analysis is necessary, with positive

staining for CK, EMA and S-100 protein indicating a diagnosis of

chordoma (15–18). The tumors from the patients of the

present study all tested negative in the immunohistochemical

analysis, and thus none were chordomas.

The treatment of cranial base chondromas and

chondrosarcomas is a formidable challenge. Radiotherapy for these

tumors remains controversial (19–21),

but several studies have shown that proton-beam radiation achieves

high rates of local tumor control and survival following maximal

surgical resection (22–25). Surgical resection still plays a

major role in the treatment for these tumors, but due to the

invasion into cranial nerves and critical vascular structures, the

goal of total tumor resection is difficult to achieve. The most

effective surgery must remove the tumor tissue completely and avoid

the incidence of complications overall (26–31).

In the present study, this latter strategy was undertaken,

resulting in no mortalities, a mean survival time similar to other

studies and excellent follow-up outcomes.

The selection of surgical approaches to the tumors

are discussed in certain studies (29,31).

In order to plan the surgical approaches more accurately, the

chondromas and chondrosarcomas of the cranial base are classified

as the parasellar, straddle and posterior cranial fossa types,

separating types by the location and growth direction of tumors.

Patients with the parasellar type usually have deficits of cranial

nerves III to VI, the most common being a sixth nerve palsy. The

frontotemporal or preauricular subtemporal-infratemporal approach

should be applicable to these patients. Tumors of the straddle type

extend from the middle fossa to the posterior cranial fossa.

Patients with this type have deficits of cranial nerves III to

VIII. The tempo-occipital transtentorial or presigmoid

supratentorial-infratentorial approach may be applicable to the

patients with this type. The suboccipital far-lateral approach or

the retrosigmoid approach can be used for the patients with the

posterior cranial fossa type, who present with deficits of cranial

nerves VII, VIII and the lower cranial nerves. The selection of

suitable approaches is extremely significant in the direct

visualization of tumors. Furthermore, skilled microsurgical

techniques and good surgical judgment learned from experience are

also essential to achieve a complete resection (29,31).

These techniques and methods, as applied to the patients in the

present study, likely contributed to the positive outcomes

reported.

Chondromas and chondrosarcomas of the cranial base

are deeply located and surrounded by significant complex

neurovascular structures, thus surgical removal is challenging. In

the majority of cranial base chondromas or chondrosarcomas, the

pre-operative diagnosis can be presumed on the basis of

neuroradiological examinations and presenting symptoms and signs.

Occasionally it is difficult to differentiate

chondrosarcomas/chondromas from chordomas, and immunohistochemistry

is useful for the this purpose. Surgical resection is the principal

treatment for cranial base chondromas or chondrosarcomas; this can

prolong survival rates, but the surgical approach must be carefully

planned for the individual tumor type and location.

Abbreviations:

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

ICA

|

internal carotid artery

|

|

KPS

|

Karnofsky performance score

|

References

|

1

|

Bloch OG, Jian BJ, Yang I, Han SJ, Aranda

D, Ahn BJ and Parsa AT: A systematic review of intracranial

chondrosarcoma and survival. J Clin Neurosci. 16:1547–1551.

2009.

|

|

2

|

Bloch OB, Jian BJ, Yang I, Han SJ, Aranda

D, Ahn BJ and Parsa AT: Cranial chondrosarcoma and recurrence.

Skull Base. 20:149–156. 2010.

|

|

3

|

Knott PD, Gannon FH and Thompson LD:

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the sinonasal tract: a

clinicopathological study of 13 cases with a review of the

literature. Laryngoscope. 113:783–790. 2003.

|

|

4

|

Scheithauer BW and Rubinstein LJ:

Meningeal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma: report of eight cases with

review of literature. Cancer. 42:2744–2752. 1978.

|

|

5

|

Heffelfinger MJ, Dahlin DC, MacCarty CS

and Beabout JW: Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors at the skull

base. Cancer. 32:410–420. 1973.

|

|

6

|

Gay E, Sekhar LN, Rubinstein E, Wright DC,

Sen C, Janecka IP and Snyderman CH: Chordomas and chondrosarcomas

of the cranial base: results and follow up of 60 cases.

Neurosurgery. 36:887–897. 1995.

|

|

7

|

Neff B, Sataloff RT, Storey L, Hawkshaw M

and Spiegel JR: Chondrosarcoma of the skull base. Laryngoscope.

112:134–139. 2002.

|

|

8

|

Launay M, Fredy D, Merland JJ and Bories

J: Narrowing and occlusion of arteries by intracranial tumors.

Review of the literature and report of 25 cases. Neuroradiology.

14:117–126. 1977.

|

|

9

|

Geibprasert S, Pongpech S, Armstrong D and

Krings T: Dangerous extracranial-intracranial anastomoses and

supply to the cranial nerves: vessels the neurointerventionalist

needs to know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 30:1459–1468. 2009.

|

|

10

|

Traflet RF, Babaria AR, Barolat G, Doan

HT, Gonzalez C and Mishkin MM: Intracranial chondroma in a patient

with Ollier’s disease: Case report. J Neurosurg. 70:274–276.

1989.

|

|

11

|

Noël G, Feuvret L, Calugaru V, Hadadi K,

Baillet F, Mazeron JJ and Habrand JL: Chondrosarcomas of the base

of the skull in Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s syndrome - three

case reports and review of the literature. Acta Oncol. 43:705–710.

2004.

|

|

12

|

Seizeur R, Forlodou P, Quintin-Roue I,

Person H and Besson G: Chondrosarcoma of the skull base in

Maffucci’s syndrome. Br J Neurosurg. 22:778–780. 2008.

|

|

13

|

Tibbs RE Jr and Bowles AP Jr: Maffucci’s

syndrome associated with a cranial base chondrosarcoma: case report

and literature review. Neurosurgery. 43:3971998.

|

|

14

|

Tachibana E, Saito K, Takahashi M, Fukuta

K and Yoshida J: Surgical treatment of a massive chondrosarcoma in

the skull base associated with Maffucci’s syndrome: a case report.

Surg Neurol. 54:165–170. 2000.

|

|

15

|

Ramina R, Coelho Neto M, Meneses MS and

Pedrozo AA: Maffucci’s syndrome associated with a cranial base

chondrosarcoma: case report and literature review. Neurosurgery.

41:269–272. 1997.

|

|

16

|

Nakayama Y, Takeno Y, Tsugu H and Tomonaga

M: Maffucci’s syndrome associated with intracranial chordoma: case

report. Neurosurgery. 34:907–909. 1994.

|

|

17

|

Korten AG, ter Berg HJ, Spincemaille GH,

van der Laan RT and Van de Wel AM: Intracranial chondrosarcoma:

review of the literature and report of 15 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 65:88–92. 1998.

|

|

18

|

Lanzino G, Dumont AS, Lopes MS and Laws ER

Jr: Skull base chordomas: overview of disease, management options,

and outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 10:E122001.

|

|

19

|

Tzortzidis F, Elahi F, Wright DC, Temkin

N, Natarajan SK and Sekhar LN: Patient outcome at long-term

follow-up after aggressive microsurgical resection of cranial base

chondrosarcomas. Neurosurgery. 58:1090–1098. 2006.

|

|

20

|

Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD and Flickinger

JC: The role of radiosurgery in the management of chordoma and

chondrosarcoma of the cranial base. Neurosurgery. 29:38–46.

1991.

|

|

21

|

Krishnan S, Foote RL, Brown PD, Pollock

BE, Link MJ and Garces YI: Radiosurgery for cranial base chordomas

and chondrosarcomas. Neurosurgery. 56:777–784. 2005.

|

|

22

|

Hug EB, Loredo LN, Slater JD, DeVries A,

Grove RI, Schaefer RA, Rosenberg AE and Slater JM: Proton radiation

therapy for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base. J

Neurosurg. 91:432–439. 1999.

|

|

23

|

Hug EB and Slater JD: Proton radiation

therapy for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base.

Neurosurg Clin N Am. 11:627–638. 2000.

|

|

24

|

Amichetti M, Amelio D, Cianchetti M,

Maurizi Enrici R and Minniti G: A systematic review of proton

therapy in the treatment of chondrosarcoma of the skull base.

Neurosurg Rev. 33:155–165. 2010.

|

|

25

|

Muthukumar N, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD

and Flickinger JC: Stereotactic radiosurgery for chordoma and

chondrosarcoma: further experiences. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

41:387–392. 1998.

|

|

26

|

Oghalai JS, Buxbaum JL, Jackler RK and

McDermott MW: Skull base chondrosarcoma originating from the

petroclival junction. Otol Neurotol. 26:1052–1060. 2005.

|

|

27

|

Förander P, Rähn T, Kihlström L, Ulfarsson

E and Mathiesen T: Combination of microsurgery and gamma knife

surgery for the treatment of intracranial chondrosarcomas. J

Neurosurg. 105(Suppl): 18–25. 2006.

|

|

28

|

Crockard HA, Cheeseman A, Steel T, Revesz

T, Holton JL, Plowman N, Singh A and Crossman J: A

multidisciplinary team approach to skull base chondrosarcomas. J

Neurosurg. 95:184–189. 2001.

|

|

29

|

Samii A, Gerganov V, Herold C, Gharabaghi

A, Hayashi N and Samii M: Surgical treatment of skull base

chondrosarcomas. Neurosurg Rev. 32:67–75. 2009.

|

|

30

|

Sekhar LN, Pranatartiharan R, Chanda A and

Wright DC: Chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base: results

and complications of surgical management. Neurosurg Focus.

10:E22001.

|

|

31

|

Wanebo JE, Bristol RE, Porter RR, Coons SW

and Spetzler RF: Management of cranial base chondrosarcomas.

Neurosurgery. 58:249–255. 2006.

|