Introduction

Metformin is one of the first-line drugs used for

type 2 diabetes treatment and has been used for over half a

century. Recent studies found that metformin not only effectively

reduced hepatic glucose production and increased insulin

sensitivity, but that it also was effective in decreasing the risk

of cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes, inhibiting the growth

of cancer cells and enhancing the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs

(1).

The potentially beneficial effects of metformin

against cancer are believed to be mediated mainly by 5′-adenosine

monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a well-conserved

energy sensor that plays a key role in the regulation of protein

and lipid metabolism in response to changes in fuel availability.

Activated AMPK inhibits cell growth and proliferation, and

therefore antagonizes cancer cell growth (2).

However, more recent data have indicated that

metformin can inhibit proliferation and sensitize cancer cells to

anticancer drugs through the inhibition of HO-1, by targeting

Raf-ERK-Nrf2 signaling in an AMPK-independent manner. Therefore,

the mechanisms of the suppression of cancer cell growth by

metformin remain unclear (3).

Previous studies have demonstrated the inhibition of

metformin on cancer cells (3–7). In

the present study, we aimed to understand the anti-tumor molecular

mechanisms of metformin.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture conditions

The human mammary carcinoma T47D cell line was

purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA,

USA). The T47D cells were maintained with RPMI 1640 (Gibco,

Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with

10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA,

USA), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cells

were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2. Additionally, 0.25%

trypsin was purchased from Gibco. Metformin was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis

The T47D cells were cultured in 6-well plates and

treated with 4 mM metformin for 48 h, then fixed by 70% ethyl

alcohol, which was subsequently removed by centrifugation at 250 ×

g for 5 min. RNase A was added in for 30 min. Following propidium

iodide staining, the cell cycle was detected with a FACSCalibur

flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Western blotting analysis

Western blotting was conducted, as previously

described (7,8). For histone extraction, the cells were

lysed with ice-cold NETN buffer containing 10 mM NaF and 50 mM

β-glycerophosphate, and following centrifugation at 250 × g for 5

min, the remaining pellets were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and

then treated with 200 μl 0.2 HCl. The supernatants were neutralized

with 40 μl 1N NaOH, and the sample was loaded onto 12.5% SDS-PAGE

gels for western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Monoclonal

rabbit anti-human anti-phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Ser79)

(pACC1), monoclonal rabbit anti-human anti-phospho-AMPKα

(Thr172)(p-AMPKα1), monoclonal rabbit anti-human

anti-ubiquityl-histone H2B (Lys120) (H2B K120ub) and rabbit

monoclonal anti-human anti-AMPKα1 were purchased from Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA), with the exception

of monoclonal mouse anti-human β-actin, was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich.

Quantitative (q)PCR

Total mRNA was isolated from the cells with TRIzol

(Invitrogen Life Technolgies), and then complementary DNA (cDNA)

was synthesized from 500 ng total RNA with the

PrimeScript® 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara

Biotechnology, Dalian, China). qPCR was performed on a 7500RT-PCR

System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the SYBR

Green detection system with the following program: 95°C for 5 min

for 1 cycle, followed by 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 45 sec for 40

cycles. The relative expression of the target genes, including p21,

cyclin D1, Tulp4 and β-actin, was represented by 2−ΔΔCT.

All samples were normalized to the β-actin mRNA levels, and the

relative expression of the mRNA of every treatment group was

calculated. The experiment was duplicated three times. The primer

sequences that were used are as follows: Cyclin D1 forward,

5′-ACGCTTCCTCTCCAGAGTGAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGACTCCAGCAGGGCTT-3′;

Tulp4 forward, 5′-GGGCCACAATAGCGAGGTT-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCACACGAATATGCCTCCGT-3′; p21 forward, 5′-TGTCCGTCAGAACCCATGC-3′

and reverse, 5′-AAAGTCGAAGTTCCATCGCTC-3′; and β-actin forward,

5′-GTCTGCCTTGGTAGTGGATAATG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCGAGGACGCCCTATCATGG-3′.

Cell proliferation

The CellTiter-Blue assay kit (Promega, Southampton,

UK) was used to measure the number of cells, according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, in a 96-well plate, the cells

were washed three times with PBS and 20 μl of CellTiter-Blue

reagent (Promega) was added. The plate was incubated for 4 h

protected from light, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded

(excitation, 560 nm; emission, 590 nm) on a Tecan M200 microplate

reader (Tecan Australia, Port Melbourne, Vic, Australia).

Small interfering (si)RNA

transfections

siRNA targeting AMPKα1 and a siRNA transfection

reagent were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa

Cruz, CA, USA). The T47D cells, grown to 50% confluence, were

transfected with AMPKα1siRNA or a non-specific control siRNA. After

48 h, the cells were used for experimentation.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 13.0

software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For comparisons between

multiple groups, a one-way analysis of variance was used, while for

a comparison between two groups, the SNK method was used. For

comparisons between the treatment and control groups, Dunnett’s

t-test was used, and for the analysis of differences between

groups, the Student’s t-test was used. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Metformin inhibits breast cancer cell

proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest

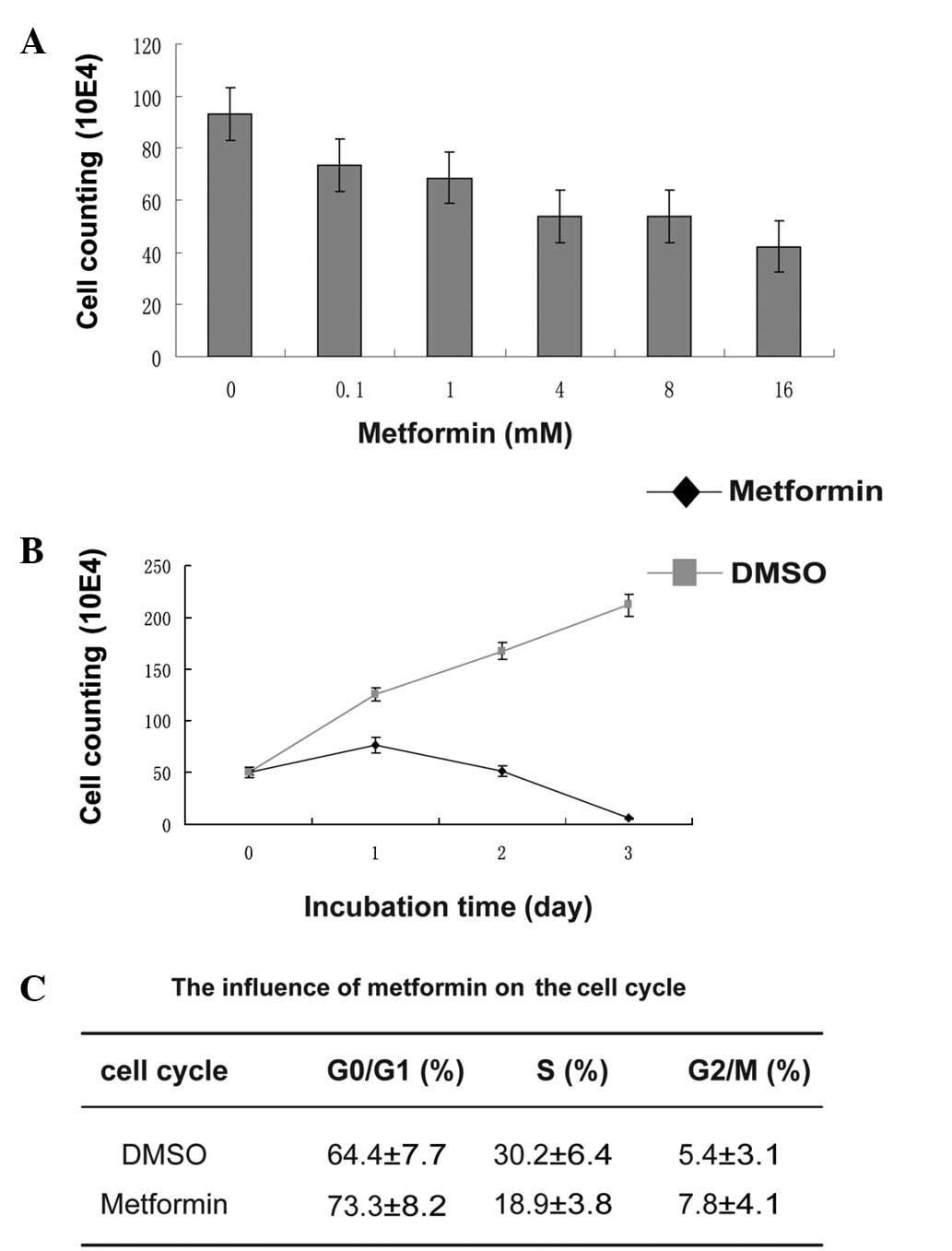

To detect the effect of metformin on breast cancer

cell proliferation, the T47D cells were treated with increasing

doses of metformin for 24 h. The inhibition of T47D cell growth by

metformin occurred in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). The cells were almost completely

killed by 8 mM metformin for 72 h (Fig.

1B). The cell cycle of the T47D cells was analyzed by flow

cytometer following treatment with 4 mM metformin for 48 h; the

ratio of the cells in G0/G1 phase increased

from 64.4 to 73.3%, while that of cells in the S-phase dropped from

30.2 to 18.9% (Fig. 1C). These

results showed that metformin significantly inhibited the

proliferation of the cells and induced cell cycle arrest.

Metformin activates AMPK and inhibits

histone H2B monoubiquitination and downstream gene

transcription

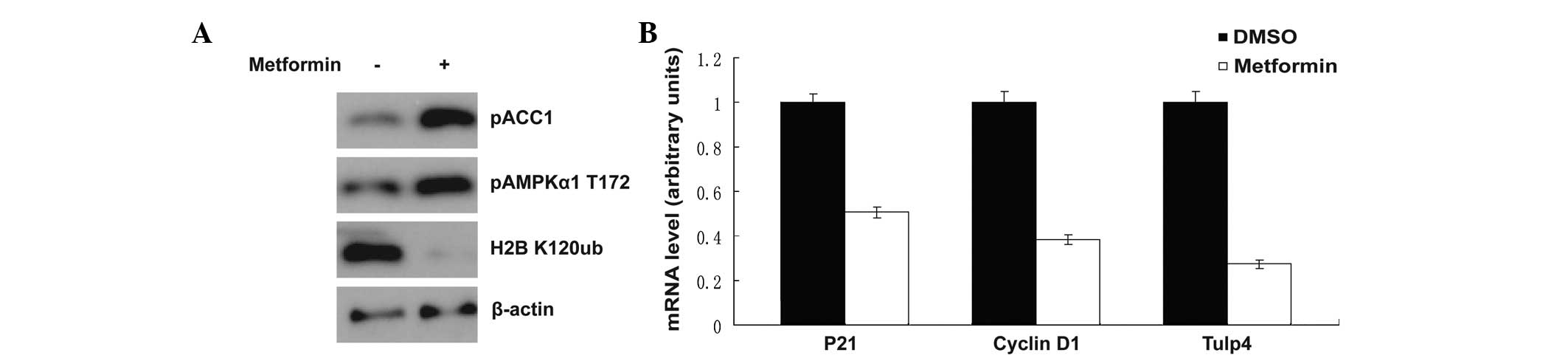

Metformin is a well-known AMPK activator. Upon

treatment with metformin, AMPK was activated, as shown in Fig. 2A, AMPK threonine 172 phosphorylation

was increased and the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase at

serine 79 was markedly enhanced (Fig.

2A). This result was consistent with the results of previous

studies (5–9). Notably, histone H2B monoubiquitination

at lysine 120 was inhibited at the same time. It was reported

previously that when the cells were suffering a shortage of

glucose, the H2B monoubiquitination at lysine 120 was also

inhibited (10). The H2B

monoubiquitination at lysine 120 was associated with the

transcription of multiple downstream target genes (11,12).

In the present study, transcription of the downstream genes,

including p21, cyclin D1 and Tulp4, was detected by qPCR, and the

mRNA level was shown to be decreased significantly following

exposure to metformin (Fig.

2B).

Metformin inhibits breast cancer cell

proliferation, which is dependent on AMPK

Since metformin efficiently activated the AMPK

signal transduction pathway, the study also detected whether the

inhibition of cell proliferation by metformin was AMPK-dependent.

AMPKα1 protein was specifically knocked down by AMPKα1 siRNA

(Fig. 3A). The AMPKα1 siRNA and

control groups were then treated with 4 mM metformin for 24 h. The

inhibition of T47D cell proliferation by metformin was found to be

less effective in the AMPKα1 siRNA group (Fig. 3B). This experiment confirmed that

the inhibition of cell proliferation by metformin was

AMPK-dependent.

Discussion

An increasing number of studies are showing that

diabetic patients treated with metformin have a lower incidence of

cancer compared with those on other treatments (6,13,14).

Another large case-control study has indicated that metformin may

somewhat reduce the incidence of pancreatic cancer (15). Early-stage clinical trials are

currently underway to investigate the potential of metformin to

prevent an array of cancers, including colorectal, prostate,

endometrial and breast cancer (16–18).

However, the underlying mechanism remains to be fully

elucidated.

A few of the beneficial effects of metformin have

been shown to work through the activation of AMPK. Treatment with

metformin results in the activation of AMPK in in vitro and

in vivo experiments, and the activation of AMPK is well

known to inhibit the expression of gluconeogenic genes and to

promote the expression of enzymes required for fatty acid oxidation

(19–21).

However, it has also been reported that in

AMPK-knockout cells, metformin works through inhibition of HO-1 by

targeting Raf-ERK-Nrf2 signaling, which indicates that a novel

mechanism is present (3).

The results of the present study indicated that

metformin significantly inhibited the proliferation of the breast

cancer cells and induced cell cycle arrest in an AMPK-dependent

manner. This is consistent with the results of previous studies.

Further molecular mechanism studies showed that metformin activates

the AMPK signal transduction pathway, promoting the phosphorylation

of ACC1, so that the synthesis of fatty acids of carcinoma cells is

inhibited. As a result, the proliferation of the cells was reduced.

Unexpectedly, metformin was able to inhibit histone H2B K120-ub,

which is related to the transcription of downstream target genes,

such as p21 and cyclin D1, which function as regulators of the cell

cycle (11,12). The results of qPCR detection

indicated that the transcription of p21, Tulp4 and cyclin D1 was

inhibited by metformin. This partially explained the mechanism by

which metformin blocks the cell cycle.

The present study revealed the possible novel

anticancer mechanism of metformin. However, the manner by which

metformin inhibits H2B monoubiquitination remains unknown. It is

presumed that metformin can activate AMPK, which phosphorylates a

certain substrate. This substrate is capable of inhibiting the

histone ubiquitination mediated by E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase.

Further studies should be performed on the relevant molecular

mechanism involved.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Hubei province, China (grant no. 2008CDB168).

References

|

1

|

Li Q, Guo D, Dong Z, et al: Ondansetron

can enhance cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity via inhibition of

multiple toxin and extrusion proteins (MATEs). Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 273:100–109. 2013.

|

|

2

|

Hardie DG: AMP-activated/SNF1 protein

kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 8:774–785. 2007.

|

|

3

|

Do MT, Kim HG, Khanal T, et al: Metformin

inhibits heme oxygenase-1 expression in cancer cells through

inactivation of Raf-ERK-Nrf2 signaling and AMPK-independent

pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 271:229–238. 2013.

|

|

4

|

Lettieri Barbato D, Vegliante R, Desideri

E and Ciriolo MR: Managing lipid metabolism in proliferating cells:

New perspective for metformin usage in cancer therapy. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1845:317–324. 2014.

|

|

5

|

Leverve XM, Guigas B, Detaille D, et al:

Mitochondrial metabolism and type-2 diabetes: a specific target of

metformin. Diabetes Metab. 29:6S88–6S94. 2003.

|

|

6

|

Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM,

Alessi DR and Morris AD: Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in

diabetic patients. BMJ. 330:1304–1305. 2005.

|

|

7

|

Anastasiou D: Metformin: a case of divide

and conquer. Breast Cancer Res. 15:3062013.

|

|

8

|

Isakovic A, Harhaji L, Stevanovic D, et

al: Dual antiglioma action of metformin: cell cycle arrest and

mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 64:1290–1302.

2007.

|

|

9

|

Kemp BE, Stapleton D, Campbell DJ, et al:

AMP-activated protein kinase, super metabolic regulator. Biochem

Soc Trans. 31:162–168. 2003.

|

|

10

|

Sanders MJ, Grondin PO, Hegarty BD,

Snowden MA and Carling D: Investigating the mechanism for AMP

activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Biochem J.

403:139–148. 2007.

|

|

11

|

Zhu B, Zheng Y, Pham AD, et al:

Monoubiquitination of human histone H2B: the factors involved and

their roles in HOX gene regulation. Mol Cell. 20:601–611. 2005.

|

|

12

|

Fujiki R, Hashiba W, Sekine H, et al:

GlcNAcylation of histone H2B facilitates its monoubiquitination.

Nature. 480:557–560. 2011.

|

|

13

|

Decensi A, Puntoni M, Goodwin P, et al:

Metformin and cancer risk in diabetic patients: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 3:1451–1461. 2010.

|

|

14

|

Noto H, Goto A, Tsujimoto T and Noda M:

Cancer risk in diabetic patients treated with metformin: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 7:e334112012.

|

|

15

|

Lee MS, Hsu CC, Wahlqvist ML, Tsai HN,

Chang YH and Huang YC: Type 2 diabetes increases and metformin

reduces total, colorectal, liver and pancreatic cancer incidences

in Taiwanese: a representative population prospective cohort study

of 800,000 individuals. BMC Cancer. 11:202011.

|

|

16

|

Belfiore A and Frasca F: IGF and insulin

receptor signaling in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol

Neoplasia. 13:381–406. 2008.

|

|

17

|

Slomiany MG, Black LA, Kibbey MM, Tingler

MA, Day TA and Rosenzweig SA: Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

and ligand targeting in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Lett. 248:269–279. 2007.

|

|

18

|

Weiss JM, Huang WY, Rinaldi S, et al:

IGF-1 and IGFBP-3: Risk of prostate cancer among men in the

Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Int

J Cancer. 121:2267–2273. 2007.

|

|

19

|

Dowling RJ, Zakikhani M, Fantus IG, Pollak

M and Sonenberg N: Metformin inhibits mammalian target of

rapamycin-dependent translation initiation in breast cancer cells.

Cancer Res. 67:10804–10812. 2007.

|

|

20

|

Zakikhani M, Dowling R, Fantus IG,

Sonenberg N and Pollak M: Metformin is an AMP kinase-dependent

growth inhibitor for breast cancer cells. Cancer Res.

66:10269–10273. 2006.

|

|

21

|

Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, et al:

The LKB1 tumor suppressor negatively regulates mTOR signaling.

Cancer Cell. 6:91–99. 2004.

|