Introduction

Odontogenic myxomas (OMs) are benign, slow-growing,

locally aggressive and non-metastasizing neoplasms of the jaw bone.

OM is derived from embryonic mesenchymal elements of the dental

anlage (1–3). According to the World Health

Organization, OM is a benign tumor of ectomesenchymal origin with

or without odontogenic epithelium (4). OM accounts for 0.5–20% of all

odontogenic tumors (5,6). OM often occurs in individuals who are

between their second and forth decades, has a slight predilection

for females and is rarely found in children and the elderly

(3). The majority of lesions that

are without pain reach a large size and cause displacement of the

teeth and asymmetry of the mandible or maxilla prior to discovery

(7).

OM of the maxilla was first reported by Thoma and

Goldman in 1947 (8). While OMs

predominantly involve the mandible, maxillary tumors are more

aggressive than those in the mandible (9). Certain lesions spread with progressive

pain through the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity, and severe cases

result in exopthalmus, nasal obstruction and neurological

disturbance (7,10). The surgical treatment of OM,

including curettage and radical resection, is controversial due to

the varying recurrence rates (9,11).

The present study reports the case of a male patient

with a large maxillary OM. Although the mass was removed

successfully, repairing the defect in the maxilla was a complex

process. Patient provided written informed consent.

Case report

Patient presentation

A 37-year-old male presented with a mass on the

right side of the face, which had persisted for five years, with

accelerated growth for one year, causing serious facial deformity

and difficulty in eating. The painless mass was ~16×16 cm and

occupied the right maxilla and the nose, extending superoinferiorly

from the right orbit and infraorbital rim to the bilateral alveolar

bone and hard palate. Part of the mass displaced the teeth and

protruded outward from the mouth, with a rough surface that

released a purulent discharge upon palpation. No superficial

ulceration, sinuses or fistulas were observed on the overlying

skin, which did not adhere to the mass. The patient had bilateral

nasal obstruction with effluvial secretion and normal vision, even

though the infraorbital rim disappeared, as the mass displaced the

optic nerve (Fig. 1).

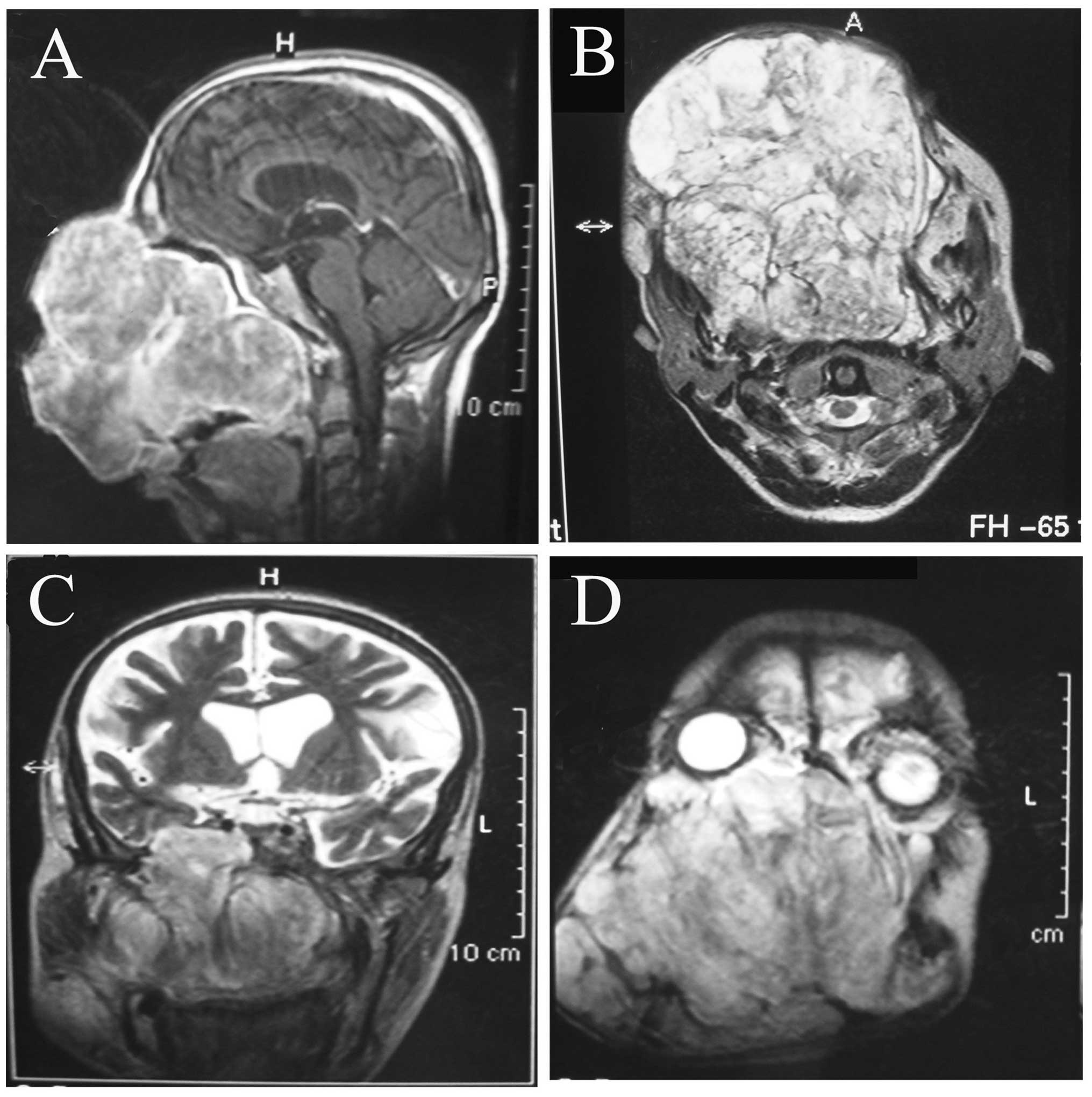

Clinical and imaging analyses

Enhanced computed tomography revealed that an

irregular and low-density shadow without obvious enhancement was

displaced in the maxillae, and that a high-density shadow was

interspersed in it. Magnetic resonance imaging identified that the

well-circumscribed tumor had already obliterated the maxillae, the

maxillary process of the right zygomatic bone, part of the left

maxilla, the ethmoidal sinuses, the sphenoid sinus and the nasal

cavity. The nasopharyngeal cavity and the left maxillary sinus were

observed to be narrow, and the turbinate bones and the nasal septum

had been resorbed due to the tumor pressure. Although the large

mass grew into the intracranial cavity through a bone defect in the

sphenoid wing caused by tumor pressure-induced resorption, the

tumor was present with well-defined borders under the dura mater

(Fig. 2). According to the clinical

and imaging examinations, it was hypothesized that the tumor may be

a mesenchymal benign tumor with malignant transformation.

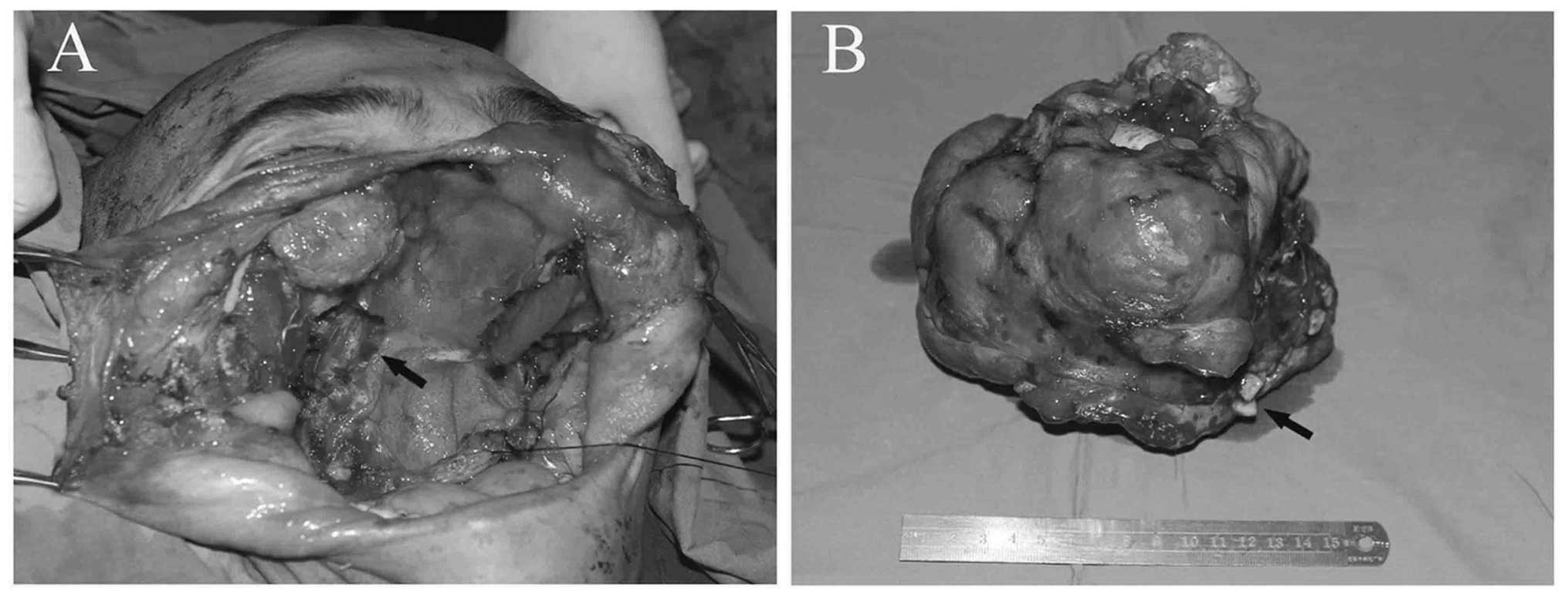

Surgery

Following a tracheostomy, the patient underwent

right radical maxillectomy and left partial maxillectomy, which

included the partial right zygomatic bone and zygomatic alveolar

ridge of the left maxilla, with a 1-cm healthy margin. Moreover,

the mass was enucleated from the soft tissues around its capsule. A

small quantity of bone surrounding the bone defect in the skull

base, as well as the turbinate mucosa and the thin skin covering

the mass were also resected. The medial rectus in the right eye,

the septum mucosa, the left nasal mucosa, the thin bone of the left

infraorbital rim and the residual posterior wall of the maxillary

sinus were retained. Subsequent to tumor removal, the cavernous,

ethmoid and left maxillary sinuses were exposed (Fig. 3). The patient did not undergo repair

using soft-tissue flaps due to the risk of complications and

financial constraints. Thus, the wound surface was covered with

Heal-All Rehabilitation Membrane® (heterogeneous

acellular dermal matrix of cattle; Zhenghai Biological Co., Ltd.,

Shandong, China) and the defect cavity was filled with large

numbers of staple slivers with iodoform. No intracranial infection

or cerebrospinal leakage were observed. No clinical or

radiographical signs of recurrence were observed, and the soft- and

hard-tissue defects were covered with compact mucosa after one year

of post-operative control. The right side of the patient’s face and

nasal bridge collapsed and the right eyeball moved down, as the

defects were not repaired using soft flaps.

Diagnosis

Macroscopically, the surgically resected mass

measured ~15×16×16 cm and appeared as a completely encapsulated

whitish-grey, lobulated, smooth and hard mass. Microscopically, the

tumor was composed of a faintly basophilic myxomatous ground

substance and a mount of spindle- and stellate-shaped cells.

Variable quantities of fibrous tissues were found throughout the

mucoid-rich matrix. Furthermore, minimal and inconspicuous

thin-walled vessels and residual bone fragments were interspersed

within the tumor. Islands of odontogenic epithelium, hyalinization

and calcification were not found. The mass was diagnosed as an

OM.

Discussion

An OM is a mesenchymal benign tumor with the

potential for extensive bone destruction, cortical expansion and a

relatively high recurrence rate (8,12). It

has been found that OM accounts for ~7.2% of all odontogenic tumors

and has no marked predilection in terms of gender and location

(mandible or maxilla) in the Chinese population (12,13).

By contrast, other studies have reported a male:female ratio of

between 1:2 and 1:3 and a mandible:maxilla ratio of between 2:1 and

2.5:1, particularly in African countries (12,13).

OM has been reported in individuals of a wide range of ages, with

an average age of 25.3 years old. A total of eight cases <10

years old and none >60 years old have been reported at the West

China Hospital of Stomatology (Chengdu, China) (13). The majority of patients with OM

present with a slowly increasing swelling and facial asymmetry with

infiltration. The mass is locally aggressive, particularly in the

maxilla (4,14). In the present case, the growth of

the mass had accelerated for one year prior to surgery due to the

accumulation of mucoid ground substance. Moreover, the tumor

contained residual bone fragments and nasal mucosa with tumor

infiltration.

While surgical intervention is recommended, no

consensus has been reached with regard to the surgical method for

the treatment of OM due to its aggressive nature and high rate of

recurrence, which is between 10 and 43%, particularly in patients

who are treated with curettage or local surgical excision (15). Boffano et al (11) reported that conservative surgery,

such as curettage and enucleation, should be performed when tumors

are <3 cm, while radical surgery should be performed when tumors

are large and aggressive (11,16,17).

Locally aggressive OM should be subjected to radical resection with

a margin of 0.5–1.0 cm or 1.0–1.5 cm of healthy bone (11,18).

In the present case, based on the absorption of the bilateral

maxillae and the partial right sphenoid wing, an extended resection

of the mass was performed, with 1 cm margins in the right zygomatic

bone and the zygomatic alveolar ridge of the left maxilla to

prevent recurrence. The tumor was enucleated around its complete

envelope in the soft tissue. Moreover, the thin skin covering the

mass was resected and was not found to be infiltrated in the frozen

histopathology report. A partial or radical resection was

hypothesized to be the best treatment choice for maxillary OM,

rather than conservative surgery, in order to reduce the recurrence

rate.

The development of microsurgery and reconstructive

surgery techniques have enabled the basic functional and aesthetic

aims of maxillary reconstruction to be achieved. Various methods

have been used to reconstruct maxillary defects, including

vascularized soft- or hard-tissue grafts from the radial forearm,

rectus abdominis, anterolater thigh, scapular and fibular, iliac

crest flaps, vascularized free fibular flaps and cranial bone

flaps, as well as material implants using, for example, titanium

mesh (19–23). According to the Brown classification

system for maxillary defects (24),

the patient described in the present study had defects higher than

class IV (Fig. 4), with the large

soft- and hard-tissue defects being difficult to reconstruct. In

this case, the residual thinning bones and soft tissue had

insufficient strength to support the weight of a composite bone

flap with titanium miniplates. Peng et al (20) reported that the composite fibular

flap is inadequate for restoring the maxilla and the infraorbital

area. Smolka and Iizuka (25) used

a latissimus dorsi flap/rectus abdominis flap and free iliac crest

graft to repair a class IVa defect with the highest rate of

transplant loss. Although vascularized soft-tissue flaps are not

capable of restoring the maxillary buttress, they have been

reported to fill the partial large cavity of midfacial defects and

rehabilitate the basic swallowing function of patients. In the

present case, the use of a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap and

an anterolateral femoral skin flap was proposed for the repair of

the skull base bone and maxillary defects in order to alleviate the

symptoms of right facial collapse. Secondary reconstruction with a

prosthesis was also proposed. However, the patient refused

aesthetic reconstruction.

| Figure 4Brown’s classification system for

maxillary defects (24). Vertical

component; Classes I, maxillectomy with no oroantral fistula; II,

low maxillectomy III, high maxillectomy; and IV, radical

maxillectomy. Horizontal component: I, unilateral alveolar maxilla

and resection of the hard palate; a, resection of less than or

equal to half of the alveolar and hard palate, not involving the

nasal septum or crossing the midline; b, resection of the bilateral

alveolar maxilla and hard palate, including a smaller resection

that crosses the midline of the alveolar bone, including the nasal

septum; and c, removal of the entire alveolar maxilla and hard

palate. |

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first report of such a large maxillary OM. In the present

study, without surgical intervention, the patient had a high risk

of succumbing due to increasing intracranial pressure. The mass was

removed successfully without any complications and did not recur

within one year despite the unsatisfactory results with regard to

the external facial features and their function. Due to the

structure of the maxillae and the local infiltration of OM, radical

resection may the best treatment choice for maxillary OM in hard

tissue and local resection may be best around the envelope in soft

tissue. It is difficult to restore the maxillary buttress and

achieve an optimal aesthetic appearance using current methods for

reconstructing midfacial defects due to the lack of suitable

conditions for oral rehabilitation with good dentition. Further

investigations are required to develop appropriate, satisfactory

reconstruction methods for midfacial defects.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Zhixiu He

(Department of Pathology, West China Hospital of Stomatology,

Sichuan University, Chengdu, China) for the pathological diagnosis

of the patient.

References

|

1

|

Buchner A, Merrell PW and Carpenter WM:

Relative frequency of central odontogenic tumors: a study of 1,088

cases from Northern California and comparison to studies from other

parts of the world. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 64:1343–1352. 2006.

|

|

2

|

Farman AG, Nortjé CJ, Grotepass FW, Farman

FJ and Van Zyl JA: Myxofibroma of the jaws. Br J Oral Surg.

15:3–18. 1977.

|

|

3

|

Abiose BO, Ajagbe HA and Thomas O:

Fibromyxomas of the jawbones - a study of ten cases. Br J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 25:415–421. 1987.

|

|

4

|

Kramer IRH, Pindborg JJ and Shear M:

Histological typing of odontogenic tumours. 2nd edition. Springer

Verlag; Berlin: 1991

|

|

5

|

Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P and DS:

World health organization classification of tumors. Pathology and

genetics of head and neck tumors. IARC Press; Lyon: 2006

|

|

6

|

Simon EN, Merkx MA, Vuhahula E, Ngassapa D

and Stoelinga PJ: Odontogenic myxoma: a clinicopathological study

of 33 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 33:333–337. 2004.

|

|

7

|

Shah A, Lone P, Latoo S, et al:

Odontogenic myxoma of the maxilla: A report of a rare case and

review on histogenetic and diagnostic concepts. Natl J Maxillofac

Surg. 2:189–195. 2011.

|

|

8

|

Thoma KH and Goldman HM: Central myxoma of

the jaw. Am J Oral Surg Orthod. 33:1947.

|

|

9

|

Deron PB, Nikolovski N, den Hollander JC,

Spoelstra HA and Knegt PP: Myxoma of the maxilla: a case with

extremely aggressive biologic behavior. Head Neck. 18:459–464.

1996.

|

|

10

|

Kaffe I, Naor H and Buchner A: Clinical

and radiological features of odontogenic myxoma of the jaws.

Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 26:299–303. 1997.

|

|

11

|

Boffano P, Gallesio C, Barreca A, et al:

Surgical treatment of odontogenic myxoma. J Craniofac Surg.

22:982–987. 2011.

|

|

12

|

Li TJ, Sun LS and Luo HY: Odontogenic

myxoma: a clinicopathologic study of 25 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

130:1799–1806. 2006.

|

|

13

|

Jing W, Xuan M, Lin Y, et al: Odontogenic

tumours: a retrospective study of 1642 cases in a Chinese

population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 36:20–25. 2007.

|

|

14

|

Brannon RB: Central odontogenic fibroma,

myxoma (odontogenic myxoma, fibromyxoma), and central odontogenic

granular cell tumor. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am.

16:359–374. 2004.

|

|

15

|

Lo Muzio L, Nocini P, Favia G, Procaccini

M and Mignogna MD: Odontogenic myxoma of the jaws: a clinical,

radiologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Oral

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 82:426–433. 1996.

|

|

16

|

Pahl S, Henn W, Binger T, Stein U and

Remberger K: Malignant odontogenic myxoma of the maxilla: case with

cytogenetic confirmation. J Laryngol Otol. 114:533–535. 2000.

|

|

17

|

Ogütcen-Toller M, Sener I, Kasap V and

Cakir-Ozkan N: Maxillary myxoma: surgical treatment and

reconstruction with buccal fat pad flap: a case report. J Contemp

Dent Pract. 7:107–116. 2006.

|

|

18

|

Leiser Y, Abu-El-Naaj I and Peled M:

Odontogenic myxoma - a case series and review of the surgical

management. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 37:206–209. 2009.

|

|

19

|

González-García R, Naval-Gías L,

Rodríguez-Campo FJ, Muñoz-Guerra MF and Sastre-Pérez J:

Vascularized free fibular flap for the reconstruction of mandibular

defects: clinical experience in 42 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 106:191–202. 2008.

|

|

20

|

Peng X, Mao C, Yu GY, et al: Maxillary

reconstruction with the free fibula flap. Plast Reconstr Surg.

115:1562–1569. 2005.

|

|

21

|

Swartz WM, Banis JC, Newton ED, et al: The

osteocutaneous scapular flap for mandibular and maxillary

reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 77:530–545. 1986.

|

|

22

|

Chrcanovic BR, do Amaral MB, Marigo Hde A

and Freire-Maia B: An expanded odontogenic myxoma in maxilla.

Stomatologija. 12:122–128. 2010.

|

|

23

|

Sun J, Shen Y, Li J and Zhang ZY:

Reconstruction of high maxillectomy defects with the fibula

osteomyocutaneous flap in combination with titanium mesh or a

zygomatic implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 127:150–160. 2011.

|

|

24

|

Brown JS, Jones DC, Summerwill A, et al: A

modified classification for the maxillectomy defect. Head Neck.

22:17–26. 2000.

|

|

25

|

Smolka W and Iizuka T: Surgical

reconstruction of maxilla and midface: clinical outcome and factors

relating to postoperative complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg.

33:1–7. 2005.

|