Introduction

Insulinoma is a rare tumor of the alimentary tract

originating from insulin-synthetizing pancreatic beta cells. Its

incidence is estimated at four per million individuals per year

worldwide (1). Although insulinoma

is benign in the majority of cases, it can be malignant in <10%

of patients (2). Typically,

insulinoma manifests as Whipple’s triad, which includes

hypoglycemia, elevated blood levels of insulin accompanied by a

decrease in blood glucose levels to <50 mg/dl, and normalization

of hypoglycemic signs following administration of sugar (3). Due to the low activity or abnormal

structure of synthesized hormones, certain insulinomas remain

asymptomatic until reaching considerable size, when the signs of

their compression on surrounding tissues can be observed (4). Co-existence of insulinoma and diabetes

has rarely been reported (3). This

study presents the case of a female patient with a one month

history of type 2 diabetes, who underwent surgery due to a

pancreatic tumor diagnosed as an insulinoma-type neuroendocrine

pancreatic tumor by histopathological examination. During two years

of follow-up the patient has remained in a good general condition.

The atypical symptomatology and history of the disease, as well as

the associated diagnostic challenges must be emphasized. To the

best of our knowledge, this is only the second case of the

insulinoma with elevated glucose levels in the blood to be reported

in the literature. Patient provided written informed consent.

Case report

Case presentation

A 47-year-old female without a history of acute

pancreatitis and diagnosed with type 2 diabetes one month

previously, was admitted to the Second Department of General and

Gastroenterological Surgery, Medical University of Bialystok

(Bialystok, Poland) due to a tumor of the pancreatic head which had

been diagnosed at the Regional Hospital of Lomza (Lomza, Poland)

(Fig. 1). On admission, the patient

complained of polydipsia, polyuria and periodical occurrence of

soft stool. Moreover, the patient had lost 3 kg during the past

month. No abnormalities were documented on physical examination.

The patient’s BMI was 21 kg/m2, and laboratory tests

also did not reveal any abnormalities aside from high blood glucose

levels (up to 16.8 mmol/l) and increased C peptide levels (2.17

ng/ml). A 2-h oral glucose tolerance test revealed the same levels

of C peptide (2.14 ng/ml). The concentration of bilirubin was

normal. A 5.5-cm tumor of the pancreatic head was shown on computed

tomography, compressing the interior vena cava and the right renal

vein, and segmentally displacing the duodenal loop. Following

normalization of glycemia with insulin, the patient was qualified

for scheduled surgery.

Surgery

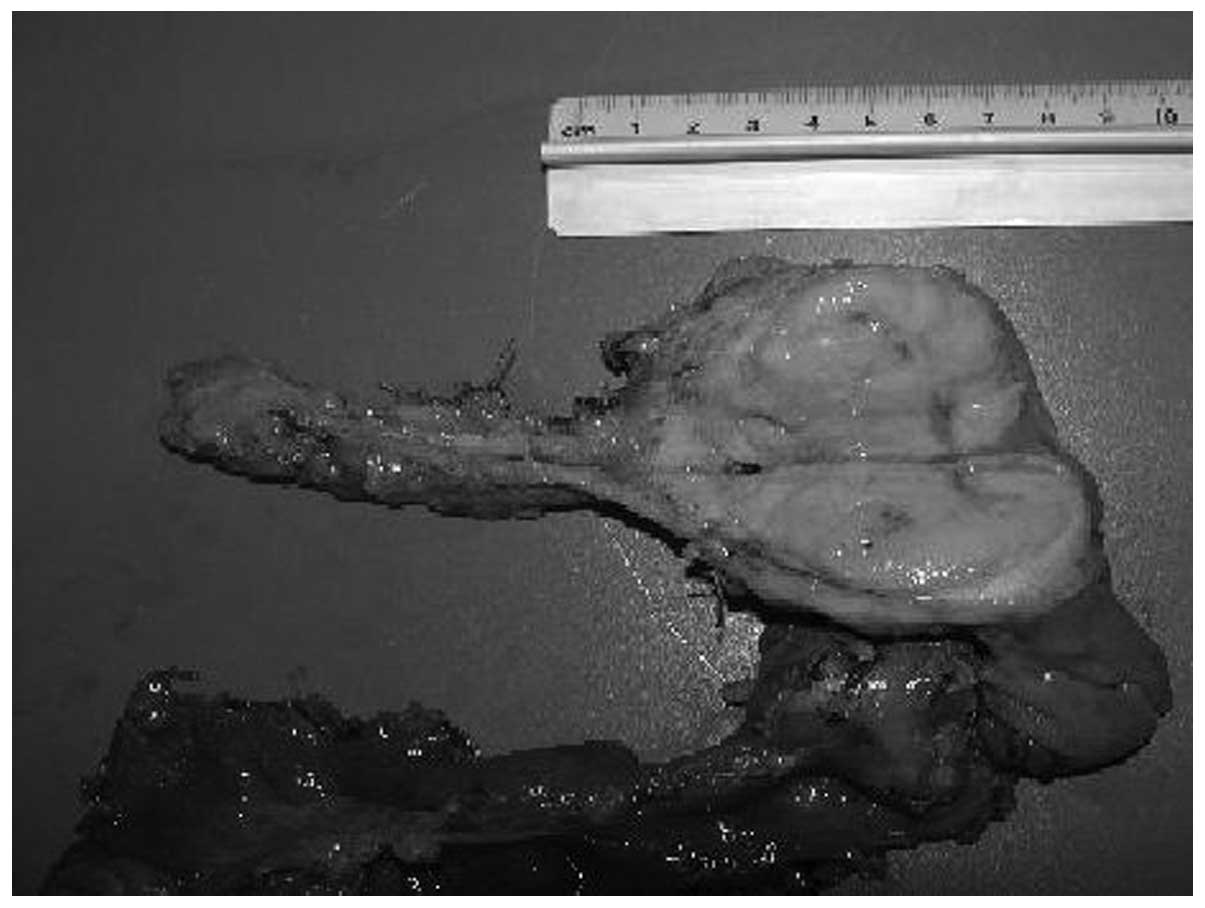

A lard-like, gray-white tumor of the pancreatic

head, measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, was revealed intraoperatively.

The tumor was observed to compress the common bile duct and the

pancreatic duct, and regression of the pancreatic body and tail

parenchyma was evident. No lymph node metastases were documented on

intraoperative microscopic examination. The pancreas was resected

completely. Due to the frozen section examination which revealed a

benign characteristic of the tumor, a pylorus-preserving

pancreticoduodenectomy was performed according to the method of

Traverso and Longmire (5), and the

regional lymph nodes were resected (Fig. 2). Pancreaticoduodenectomy remains

the standard surgical treatment for resectable tumors of the

pancreatic head (5). There was no

postoperative morbidity and, following 12 days of hospitalization,

the patient was discharged from hospital in good overall

status.

Postoperative pathological analysis

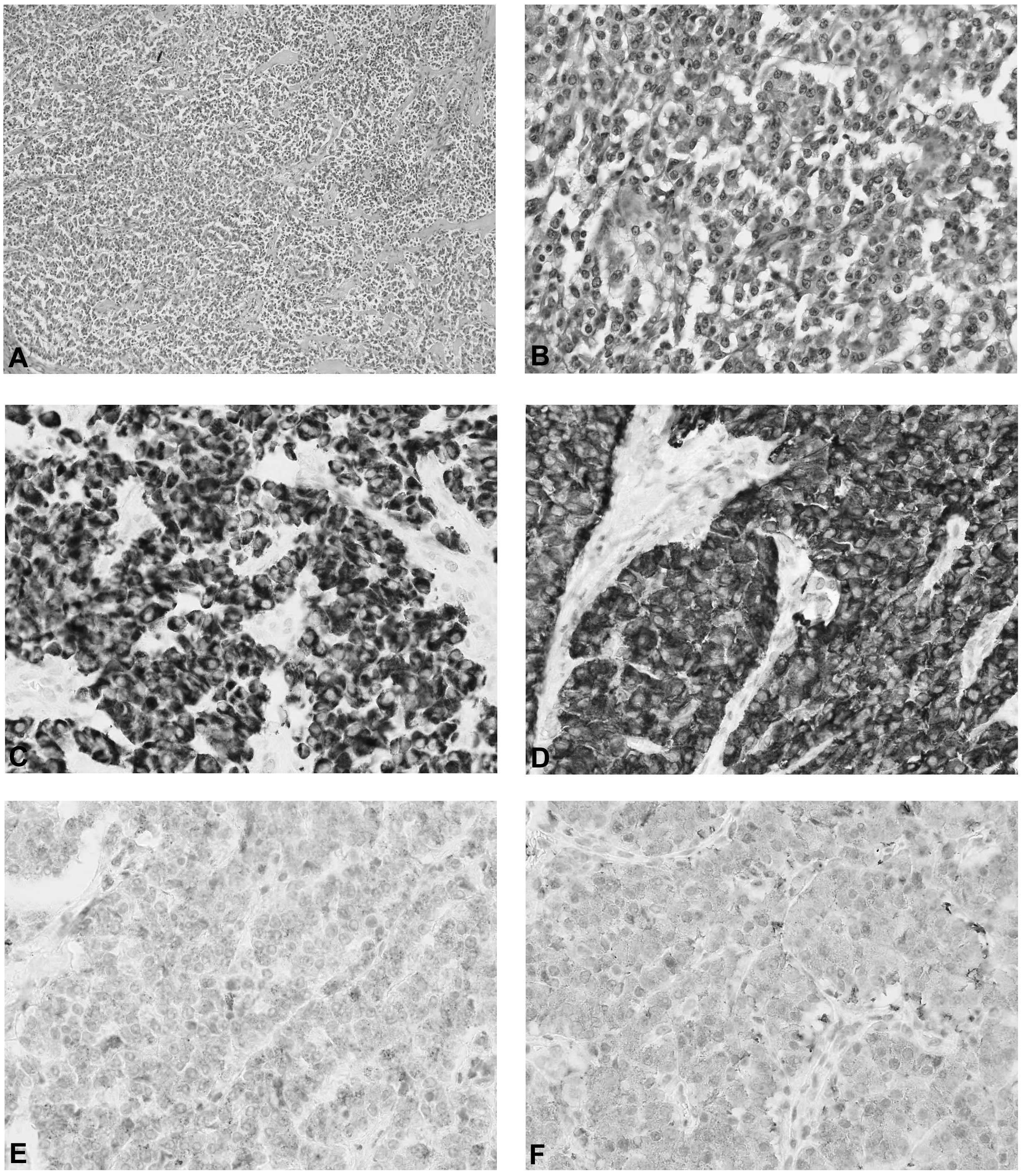

Pathomorphological examination of the surgical

specimen revealed a G2 (moderately differentiated) and pT3 (tumor

extends beyond the pancreas, but without involvement of the celiac

axis or superior mesenteric artery) tumor according to the TNM

Staging for Foregut Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Stomach, Duodenum,

and Pancreas (6). The remaining

pancreatic parenchyma showed signs of chronic fibrotic

inflammation. Immunohistochemical examination of the tumor revealed

the presence of chromogranin, synaptophysin, neuron-specific

enolase and pancytokeratin (Fig.

3). No metastases were documented in the 16 removed lymph

nodes.

Follow-up

The patient was discharged home in a good general

condition and visited the Surgical Outpatient Clinic for two weeks

following the surgery. The patient was not hospitalized during the

two years of postoperative follow-up. The patient has remains

disease-free without any complaints and with complete control of

diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors form a group of

heterogenic neoplasms originating from exocrine cells. Although

these tumors more commonly occur spontaneously, they can be

associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome in 10%

of cases. Insulinoma is a hormonally active tumor originating from

insulin-synthesizing beta cells of the pancreas. Although it is

typically benign, it can be malignant in 10% of patients. Most

(90%) insulinomas are no larger than 2 cm (7). Due to their small size, the

sensitivity of ultrasound and computed tomography in detection of

insulinoma is low (sensitivity range, 23–63 and 40–73%,

respectively) (8).

Usually, patients are evaluated for potential

insulinoma due to hypoglycemic signs, such as hand tremor,

excessive sweating, heart palpitations, double vision and sudden

loss of consciousness. Moreover, cases in which the initial signs

of insulinoma included seizure episodes or behavioral disorders

have been reported. Abnormalities in laboratory results include

hypoglycemia associated with elevated levels of insulin and high

activity of C peptide, corresponding to the overproduction of

endogenous insulin. The supervised 72-h fast is the gold standard

test for the diagnosis of insulinoma (9). It is necessary to document

hypoglycemia during the test, as insulinoma demonstrates a too high

insulin concentration in the face of hypoglycemia. Patients with

type 2 diabetes in whom the initial manifestation of insulinoma

included a decreased demand for insulin or even a normalization of

glycemia have also been described in literature. However, the

coexistence of insulinoma with hyperglycemia, as in the present

case, has rarely been reported. Both the histopathological

examination of the tumor and elevated C peptide levels were

essential for the diagnosis of insulinoma in the current, non-obese

patient. Normal insulin levels do not exclude the possibility of

the disease, as the absolute insulin levels are not elevated in all

patients with insulinoma (10,11).

Such patients may secrete a variety of insulin precursor and/or its

fragments.

Only one such case was recorded amongst 313

insulinoma-type tumors treated at Mayo Clinic between 1927 and

1993. Moreover, only one case of insulinoma associated with

hyperglycemia was observed among 443 Japanese patients treated for

this tumor between 1976 and 1990 (12). The patient in the present case had

no history of hypoglycemic signs. Neuroendocrine tumors are

frequently asymptomatic. According to the literature, between 0.8

and 10% of tumors are detected during autopsy (13). Frequently, hormonally active tumors

do not present with symptoms specific to a given hormone, due to

the insufficient activity/quantity or the type of hormone (for

example pancreatic polypeptides do not lead to any clinical

symptoms). Kazijan et al (14) identified 50 clinically asymptomatic

cases in a group of 70 patients who underwent surgery for

neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. Frequently, the initial symptoms

of such tumors include the compression signs associated with their

overgrowth. The tumor detected in the present patient was 5.5 cm in

diameter and compressed the pancreatic duct, the common bile duct

and the duodenum. Additionally, fibrotic pancreatitis was

identified on pathomorphological examination as a potential reason

for the lack of insulin production in destroyed pancreatic islets

and hyperinsulinemia. Atypical clinical manifestation prevented the

establishment of a correct preoperative diagnosis in the present

patient. Sudden onset of diabetes in an otherwise non-obese

patient, rapid weight loss, defecation disorders, and the feeling

of weakness with associated pain could rather suggest pancreatic

adenocarcinoma.

Surgery is the basic treatment option for both

pancreatic adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors of this organ.

However, the recommendations on the optimal extent of resection

differ. Radical surgery, including resection of the pancreas and

regional lymph nodes, should be performed in adenocarcinoma cases.

By contrast, an enucleation without intact tissue margin is

sufficient in the case of small isolated neuroendocrine tumors,

enabling a 90% five-year survival rate (12). Moreover, lymphadenectomy is not

required in the case of less-advanced neuroendocrine tumors. In the

case of distant metastases, cytoreduction of the endocrine tumor

mass raises the possibility of efficient chemotherapy. In addition,

adenocarcinoma is considered non-resectable and, thus, surgery is

not advised (15). The patient in

the present case presented with clinically asymptomatic, highly

advanced pancreatic insulinoma of considerable size. Such an

unfavorable profile of prognostic factors fully substantiated

radical surgery, which was performed despite the lack of

preoperative diagnosis.

This case confirms that a correct diagnosis can only

be established on the basis of the postoperative pathomorphological

examination. In addition, due to the high malignant potential of

neuroendocrine tumours, radical surgery with regional

lymphadenectomy and intraoperative frozen section evaluation

remains the treatment of choice. In conclusion, the differential

diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours must include

insulinomas with high blood glucose levels, as certain

neuroendocrine tumors are biologically inactive.

References

|

1

|

Service FJ, McMahon MM, O’Brien PC and

Ballard DJ: Functioning insulinoma - incidence recurrence and

long-term survival of patients: a 60-year study. Mayo Clin Proc.

66:711–719. 1991.

|

|

2

|

Abbasakoor NO, Healy ML, O’Shea D, et al:

Metastatic insulinoma in a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus:

Case report and review of the literature. Int J Endocrinol.

2011:1240782011.

|

|

3

|

Karam MD and Masharani U: Hypoglycemic

disorders. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. Greenspan FS and

Gardnern DG: 7th edition. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: pp. 747–766.

2004

|

|

4

|

Chen M, Van Ness M, Guo Y and Gregg J:

Molecular pathology of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 3:182–188. 2012.

|

|

5

|

Traverso LW and Longmire WP Jr:

Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg

Gynecol Obstet. 146:959–962. 1978.

|

|

6

|

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al:

Exocrine and Endocrine Pancreas. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th

edition. Springer; New York, NY: pp. 241–249. 2010

|

|

7

|

Hashimoto LA and Walsh RM: Preoperative

localization of insulinomas is not necessary. J Am Call Surg.

189:369–373. 1999.

|

|

8

|

Ozkaya M, Yuzbasioglu MF, Koruk I, Cakal

E, Sahin M and Cakal B: Preoperative detection of insulinomas: two

case reports. Case J. 1:3622008.

|

|

9

|

Breidalh HD and Rynearson EH: Clinical

aspects of hyperinsulinism. J Am Med Assoc. 160:198–204. 1956.

|

|

10

|

Carneiro DM, Levi JU and Irvin GL III:

Rapid insulin assay for intraoperaive confirmation of complete

resection of insulinomas. Surgery. 132:937–942. 2002.

|

|

11

|

Doherty GM, Doppman JL, Shawker TH, et al:

Results of a prospective strategy to diagnose, localize, and resect

insulinomas. Surgery. 110:989–996. 1991.

|

|

12

|

Ishii H, Ito T, Moriya S, Horie Y and

Tsuchiya M: Insulinoma - a statistical review of 443 cases in

Japan. Nihon Rinsho. 51:199–206. 1993.(In Japanese).

|

|

13

|

Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J and

Petersen GM: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence,

prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Onc.

19:1727–1733. 2008.

|

|

14

|

Kazanjian KK, Reber HA and Hines OJ:

Resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: results of 70 cases.

Arch Surg. 141:765–770. 2006.

|

|

15

|

Kulke MH, Bendell J, Kvols L, Picus J,

Pommier R and Yao J: Evolving diagnostic and treatment strategies

for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Hematol Oncol.

4:292011.

|