Introduction

Schwannomas or neurilemmomas are rare neoplasms that

typically occur in the peripheral nerve sheath of the extremities.

However, visceral localization of these tumors, specifically

pancreatic schwannomas that arise from either sympathetic or

parasympathetic fibers of the pancreas, is particularly rare

(1). Pancreatic schwannomas affect

adults with an equal gender distribution. In the majority of cases,

these tumors are well-defined, encapsulated solid masses with

hemorrhage or cystic degeneration, calcification, hyalinization and

xanthomatous infiltration (1–3).

Imaging findings of pancreatic schwannomas with cystic degeneration

may present a cystic pancreatic lesion. The present study reports a

patient with a pancreatic head tumor presenting with weight loss

and abdominal pain. The pancreatic head tumor was diagnosed as a

schwannoma, which was considered to be a rare case with an unusual

localization. The patient provided written informed consent.

Case report

A 30-year-old male was admitted to the Ankara

Oncology Research and Education Hospital (Ankara, Turkey)

presenting with weight loss and abdominal pain. The patient

exhibited no other systemic symptoms. On physical examination, a

tender mass in the epigastrium was palpated. The laboratory

examination results, including hemoglobin, liver function tests,

amylase and tumor marker levels (carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and

carcinoembryonic antigen) were in the normal ranges.

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a hypoechoic mass

measuring 7.6×3 cm in the pancreatic head. Upper abdominal computed

tomography (CT) showed a hypodense mass measuring 10×7 cm arising

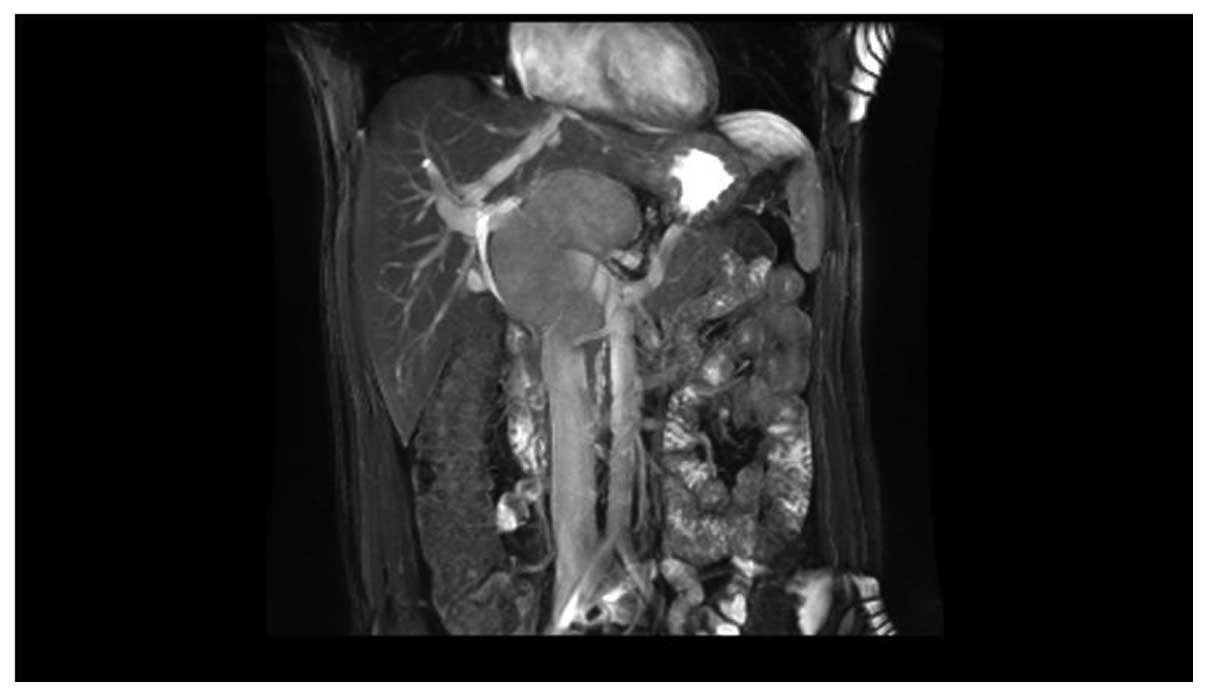

from the head of the pancreas. Upper abdominal T1-weighted dynamic

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a hypointense, bilobular,

contoured, encapsulated mass measuring 8.7×9 cm, which exhibited

cystic components arising from the head and the uncinate process of

the pancreas and portal hilus; the mass encased the superior

mesenteric artery and laterally replaced the portal vein. Following

the administration of gadolinium, an early and persistent enhanced

signal was noted in the T2-weighted fat saturation sequences

(Figs. 1 and 2), and the lesion was markedly

hyperintense (Figs. 3 and 4). Based on the patient’s history, and the

clinical and imaging findings, an ultrasonography-guided Tru-cut

needle (WestCott 16G, Beckton Dickinson, Downers Grove, IL, USA)

biopsy was performed and pathological evaluation showed

characteristic spindle cells and strong positive immunoperoxidase

staining for S-100 protein, which was consistent with schwannoma.

Therefore, a duodenopancreatectomy was performed.

Discussion

Schwannoma or neurilemmoma are rare, well-defined,

benign encapsulated, slow growing tumors arising from Schwann cells

that encase the peripheral nerves (1–3).

Extracranial schwannomas typically occur in the extremities,

however, are also found in the trunk, head and neck, pelvis and

rectum (4–10). Intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal and

particularly intra-pancreatic presentation of schwannoma is

extremely rare (9,10). The number of cases of schwannoma

located in the small bowels, bile ducts, pelvis and sacrum are

currently limited (6,11) with <26 cases of pancreatic

schwannoma reported in the literature to date. These tumors vary

considerably in size, ranging from 1.5 to 20.0 cm in diameter and

the majority of the tumors are located in the head (38%) and body

(25%) of the pancreas. Half of the reported schwannomas are cystic

and 5% of schwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis type

1.

Typical CT findings of pancreatic schwannomas are

similar to non-pancreatic schwannomas and demonstrate a

well-defined, encapsulated, hypointense solid mass with hemorrhage

or cystic degeneration, calcification or hyalinization (1–3,12).

Cystic formation may mimic cystic pancreatic lesions, such as

neuroendocrine tumors, cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, intraductal

papillary mucinous tumor, lymphangiomas and pancreatic pseudocysts

(13).

Characteristic MRI findings of these tumors include

typical encapsulation, hypointensity on T1-weighted images and

hyperintensity on T2-weighted images (13). MRI may also differentiate pancreatic

schwannoma from adenocarcinoma due to the characteristic

hyperintensity on T2-weighted images and marked enhancement of the

lesion in comparison with the remainder of the pancreas.

In the present case, the tumor was an encapsulated

pancreatic mass with cystic components. Although CT and MRI may aid

in the differential diagnosis, a definitive diagnosis of pancreatic

schwannoma requires histopathological examination. Microscopically,

schwannomas are strongly positive for S-100 protein, vimentin and

cluster of differentiation 56, however, are negative for other

tumor markers (14). Surgical

excision with a close follow-up and surveillance remain the

mainstay treatment method for pancreatic schwannomas.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of pancreatic

schwannomas, although they are rare, must be considered in the

differential diagnosis of well-defined, encapsulated cystic lesions

of the pancreas.

References

|

1

|

Tofigh AM, Hashemi M, Honar BN and Solhjoo

F: Rare presentation of pancreatic schwannoma: a case report. J Med

Case Rep. 2:2682008.

|

|

2

|

Di Benedetto F, Spaggiari M, De Ruvo N, et

al: Pancreatic schwannoma of the body involving the splenic vein:

case report and review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol.

33:926–928. 2007.

|

|

3

|

Okuma T, Hirota M, Nitta H, et al:

Pancreatic schwannoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 38:266–270.

2008.

|

|

4

|

Jayaraj SM, Levine T, Frosh AC and Almeyda

JS: Ancient schwannoma masquerading as parotid pleomorphic adenoma.

J Laryngol Otol. 111:1088–1090. 1997.

|

|

5

|

Dayan D, Buchner A and Hirschberg A:

Ancient neurilemmoma (Schwannoma) of the oral cavity. J

Craniomaxillafac Surg. 17:280–282. 1989.

|

|

6

|

Hide IG, Baudouin CJ, Murray SA and

Malcolm AJ: Giant ancient schwannoma of the pelvis. Skeletal

Radiol. 29:538–542. 2000.

|

|

7

|

Graviet S, Sinclair G and Kajani N:

Ancient schwannoma of the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 34:46–50.

1995.

|

|

8

|

McCluggage WG and Bharucha H: Primary

pulmonary tumours of nerve sheath origin. Histopathology.

26:247–254. 1995.

|

|

9

|

Loke TH, Yuen NW, Lo KK, Lo J and Chan JC:

Retroperitoneal ancient schwannoma: review of clinico-radiological

features. Australas Radiol. 42:136–138. 1998.

|

|

10

|

Giglio M, Giasotto V, Medica M, Germinale

F, Durand F, Queirolo G and Carmignani G: Retroperitoneal ancient

schwannoma: case report and analysis of clinico-radiological

findings. Ann Urol (Paris). 36:104–106. 2002.

|

|

11

|

Toh LM and Wong SK: A case of cystic

schwannoma of the lesser sac. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 35:45–48.

2006.

|

|

12

|

Tortorelli AP, Rosa F, Papa V, et al:

Retroperitoneal schwannomas: diagnostic and therapeutic

implications. Tumori. 93:312–315. 2007.

|

|

13

|

Ferrozzi F, Bova D and Garlaschi G:

Pancreatic schwannoma: report of three cases. Clin Radiol.

50:492–495. 1995.

|

|

14

|

Tan G, Vitellas K, Morrison C and Frankel

WL: Cystic schwannoma of the pancreas. Ann Diagn Pathol. 7:285–291.

2003.

|