Introduction

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD)

is a rare, but critical complication that occurs following solid

organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (1). PTLD encompasses a heterogeneous group

of disorders, ranging from benign self-limited lesions to

aggressive widely disseminated disease. Generally, PTLD is

considered to be an iatrogenic complication due to the intensive

immunosuppressive treatment administered following transplantation

(2). The overall incidence of PTLD

in adult kidney transplantation surgery was between 1 and 3%

worldwide (3). However, early-onset

PTLD (<1 year from transplantation to presentation of PTLD) is

closely associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and

exhibits a predilection for allograft localization (4), occasionally occuring at sites adjacent

to the allograft. The current study describes a rare case of PTLD

that presented as a tumor adjacent to the allograft within the

first year following renal transplantation. The treatment strategy

included surgical resection that was followed by a reduction in

immunosuppression and low-dose rituximab-based chemotherapy. This

study may lead to future improvements for the treatment of

post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Written informed

consent was obtained from the patient.

Case report

In March 2012, a 42-year-old male exhibiting

end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension received a kidney

transplant at the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South

University (Changsha, China). The donor was a 27-year-old male who

had succumbed to cardiac failure caused by craniocerebral trauma.

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) type of the donor and the

recipient were A11/A2-B58/B13-DR4/DR53, DR9/DR53 and

A2/A2-B13/B61-DR15/DR51, DR9/DR53, respectively. The recipient was

EBV seronegative, however, the donor’s EBV serologic status was

unknown, as EBV serologic status was not tested routinely at the

time of donation. Furthermore, the donor and recipient were

seronegative for cytomegalovirus, and the Hepatitis B and C

viruses. There were no complications during surgical follow-up. The

patient’s post-transplant immunosuppressive regimen included:

Intravenous methylprednisolone (dose during surgery, 0.5 g; dose

for the first three days following surgery, 0.5 g/day); followed by

cyclosporine (CsA; initial dose, 6 mg/kg/day; trough concentration

was adjusted to 220–250 ng/ml 0–6 months following transplantation

and 180–220 ng/ml over the next 6–12 months); oral mycophenolate

mofetil (MMF; dose, 0.75 g per 12 h; gradually reduced to 0.5 g per

12 h for long-term maintenance immunosuppression); and prednisolone

(initial dose, 80 mg/day; gradually reduced to 10 mg/day over the

next 6 months for long-term maintenance immunosuppression). Good

renal allograft function was observed immediately following

surgery. On the twelfth postoperative day, the patient exhibited a

serum creatinine level of 133 μmol/l (normal range, 44–133 μmol/l)

and was discharged. The allograft function remained normal during

the out-patient follow-up, however, seven months

post-transplantation, the patient developed a fever, oliguria and

an elevated serum creatinine level (410.7 μmol/l). Sonography and

computed tomography revealed a solid mass adjacent to the renal

allograft (Fig. 1A) and computed

tomography with coronal multiplanar reformation revealed a solid

mass (size, 6×4×8 cm) in the lower pole of the allograft and

hydronephrosis (Fig. 1B).

Percutaneous nephrostomy tubes were inserted, resulting in a

decline in the serum creatinine level. Subsequently, surgical

resection was performed and a tumor with a poorly defined margin,

located adjacent and in close proximity to the lower pole of the

allograft, was removed. Postoperatively, serum creatinine returned

to within the normal range following treatment of the urinary

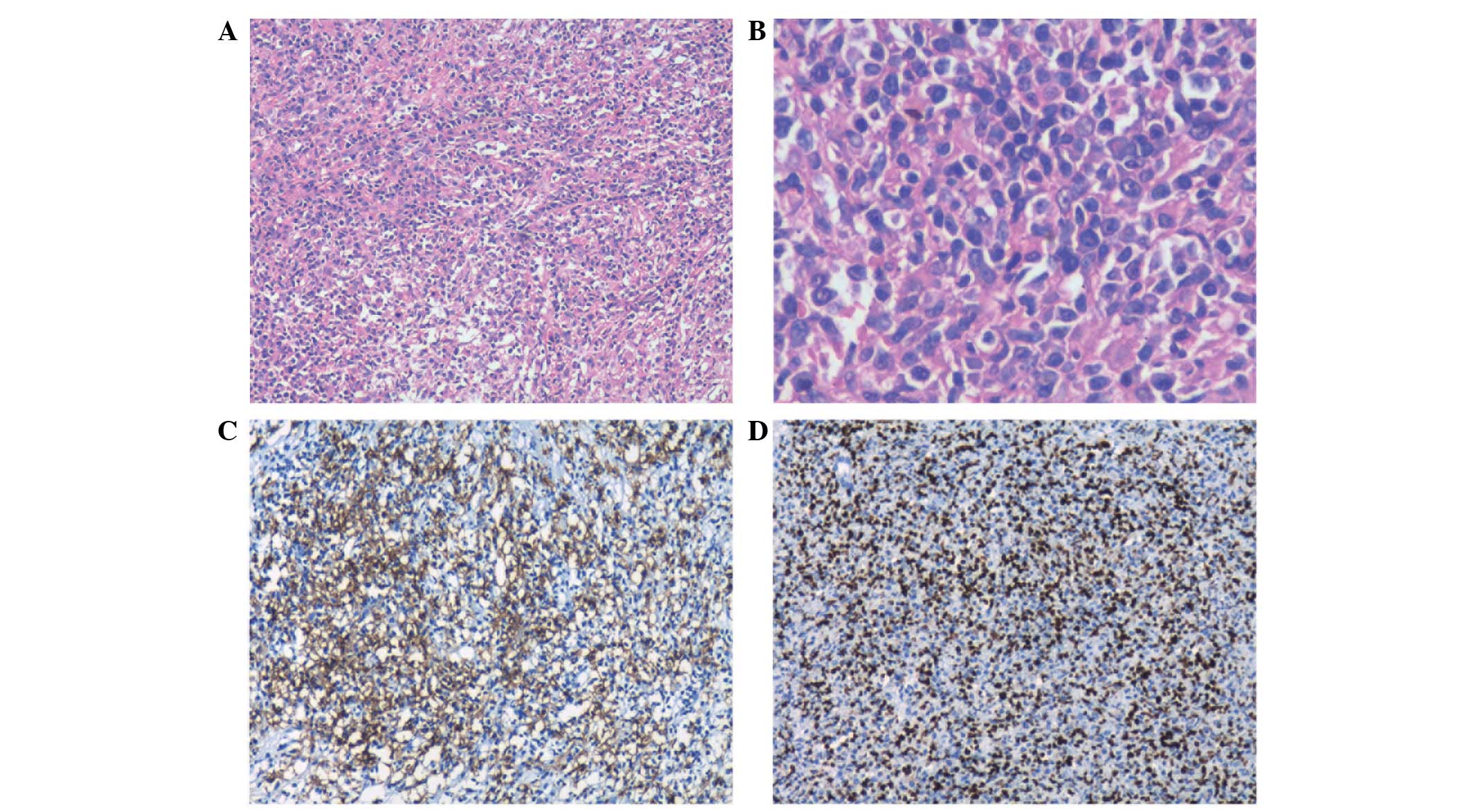

obstruction. Intra- and postoperative histopathological assessments

determined a diagnosis of polymorphic PTLD with positive stains for

cluster of differentiation (CD)20, CD79a, CD3 and EBV-encoded RNA

(Fig. 2). The proliferation index

of Ki-67 was 40%. Upon diagnosis, the blood EBV DNA level was

1.3×104 copies/ml, and the lactate dehydrogenase level

(normal range, 135–215 U/l) and bone marrow biopsy were normal.

Therefore, MMF therapy was discontinued and CsA was replaced with

Rapamune (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Dallas, TX, USA) (trough

concentration adjusted to 6–8 ng/ml) to reduce the level of

immunosuppression. Furthermore, four cycles of adjuvant low-dose

chemotherapy were administered, including rituximab (300

mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2),

vincristine (1.2 mg/m2) and prednisolone (50

mg/m2). The patient’s blood was negative for EBV DNA

following the first cycle of chemotherapy. During the 16-month

follow-up after resection, the patient remained in remission,

neither EBV viremia nor PTLD recurred and renal allograft function

was preserved. Outpatient follow-up is ongoing to determine the

long-term outcome of the treatment strategy.

Discussion

PTLD is the second most commonly occurring

malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients, worldwide.

Approximately 20% of kidney transplant patients developed PTLD

within the first year following surgery (5). Early-onset PTLD occurs more commonly

in EBV seronegative recipients compared with EBV seropositive

recipients and is characterized by an EBV in situ

hybridization-positive, CD20-positive phenotype and allograft

involvement (6). An

immunosuppressed state and EBV infection are considered to be the

two most important risk factors in PTLD development (2). In the majority of EBV-associated cases

of PTLD, immunosuppression depresses the EBV-specific cellular

immune response, which may promote uncontrolled EBV-infected

lymphocyte proliferation, resulting in PTLD (7). The rare case described in the current

report presented as a tumor adjacent to the lower pole of the renal

allograft and developed into a urinary obstruction. To the best of

our knowledge, few similar cases have been reported to date

(8–12). In the present case, the risk factors

for the development of PTLD included EBV seronegativity prior to

transplantation, EBV infection post-transplantation, mismatching at

the HLA-B locus and a high dose of CsA (13,14).

No consensus on the optimal management of PTLD has

been determined, however, a reduction in immunosuppression (RI) has

been demonstrated to be an effective initial treatment modality for

PTLD. In a recent analysis of 148 solid organ transplant-associated

PTLD cases, Reshef et al (15) reported that the overall response

rate for a RI alone was 45% and the three year overall survival

rate was 55%. Recent guidelines recommend commencing the reduction

of immunosuppression therapy as soon as possible in all PTLD

patients (16) and in specific

cases of localized PTLD, surgical excision of isolated lesions or

debulking of the tumor may be an effective component of first-line

treatment. Reshef et al (15) identified that patients who underwent

surgery and adjuvant RI exhibited a favorable outcome, with 27%

patients relapsing at a median of five months. Rituximab is a

monoclonal antibody against the B lymphocyte-specific CD20 antigen

(17). Recent data indicates that

immediate commencement of rituximab-based therapy followed by

anthracycline-based chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin,

vincristine and prednisolone) may result in durable

progressive-free survival in PTLD patients (18) and may reduce the risk of renal graft

impairment following the reduction of immunosuppression (19). In the present case, surgical

excision was performed for the diagnosis and resolution of the

urinary obstruction. RI, followed by rituximab-based therapy

combined with low-dose chemotherapy, for four months, the standard

dose is as follows: rituximab (375 mg/m2, day 1),

cyclophosphamide (400 mg/m2, days 1–5), vincristine (1.4

mg/m2, day 1) and prednisolone (100 mg/m2,

days 1–5) and was prescribed due to the aggressive nature of the

disease. The therapeutic strategy administered to the patient in

the present study resulted in complete remission with few

manageable side-effects, including nausea/vomiting and leukopenia.

Consistent with the present case, two previous studies reported

that surgical intervention in combination with other therapies

achieved durable remission in specific patients exhibiting

localized PTLD (20,21). The maintenance of immunosuppression

remains a challenge in renal recipients who develop PTLD. The use

of calcineurin inhibitors has been associated with an increased

incidence of PTLD (22), however,

treatment with rapamycin and its analogs has demonstrated

immunosuppression and antiproliferative action. Previous studies

demonstrated that rapamycin immunosuppressant therapy produced

favorable effects in kidney transplant patients exhibiting PTLD

(23,24). Therefore, serolimus was introduced

in the present case for maintenance immunosuppression. However, the

use of rapamycin in PTLD patients remains controversial (25), thus, further studies are required to

reach a consensus for the optimal management of PTLD.

In conclusion, the current report presents a rare

case of PTLD that manifested as an obstructive uropathy within the

first year following kidney transplantation. Surgical excision

followed by a reduction in immunosuppression and low-dose

rituximab-based chemotherapy may present as an effective and safe

strategy for specific cases of localized and resectable PTLD.

References

|

1

|

Everly MJ, Bloom RD, Tsai DE and Trofe J:

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Ann Pharmacother.

41:1850–1858. 2007.

|

|

2

|

Dierickx D, Tousseyn T, De Wolf-Peeters C,

Pirenne J and Verhoef G: Management of posttransplant

lymphoproliferative disorders following solid organ transplant: an

update. Leuk Lymphoma. 52:950–961. 2011.

|

|

3

|

Caillard S, Lelong C, Pessione F and

Moulin B; French PTLD Working Group. Post-transplant

lymphoproliferative disorders occurring after renal transplantation

in adults: report of 230 cases from the French Registry. Am J

Transplant. 6:2735–2742. 2006.

|

|

4

|

Khedmat H and Taheri S: Early onset post

transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: analysis of

international data from 5 studies. Ann Transplant. 14:74–77.

2009.

|

|

5

|

Morton M, Coupes B, Roberts SA, et al:

Epidemiology of posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder in

adult renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 95:470–478.

2013.

|

|

6

|

Ghobrial IM, Habermann TM, Macon WR, et

al: Differences between early and late posttransplant

lymphoproliferative disorders in solid organ transplant patients:

are they two different diseases? Transplantation. 79:244–247.

2005.

|

|

7

|

Tsao L and Hsi ED: The clinicopathologic

spectrum of posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch

Pathol Lab Med. 131:1209–1218. 2007.

|

|

8

|

Kew CE II, Lopez-Ben R, Smith JK, et al:

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder localized near the

allograft in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 69:809–814.

2000.

|

|

9

|

Palmer BF, Sagalowsky AI, McQuitty DA,

Dawidson I, Vazquez MA and Lu CY: Lymphoproliferative disease

presenting as obstructive uropathy after renal transplantation. J

Urol. 153:392–394. 1995.

|

|

10

|

Khedmat H and Taheri S: Characteristics

and prognosis of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders

within renal allograft: Report from the PTLD. Int Survey Ann

Transplant. 15:80–86. 2010.

|

|

11

|

Cosio FG, Nuovo M, Delgado L, et al: EBV

kidney allograft infection: possible relationship with a peri-graft

localization of PTLD. Am J Transplant. 4:116–123. 2004.

|

|

12

|

Caillard S, Porcher R, Provot F, et al:

Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder after kidney

transplantation: report of a nationwide French registry and the

development of a new prognostic score. J Clin Oncol. 31:1302–1309.

2013.

|

|

13

|

Quinlan SC, Pfeiffer RM, Morton LM and

Engels EA: Risk factors for early-onset and late-onset

post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in kidney recipients

in the United States. Am J Hematol. 86:206–209. 2011.

|

|

14

|

Bakker NA, van Imhoff GW, Verschuuren EA,

et al: HLA antigens and post renal transplant lymphoproliferative

disease: HLA-B matching is critical. Transplantation. 80:595–599.

2005.

|

|

15

|

Reshef R, Vardhanabhuti S, Luskin MR, et

al: Reduction of immunosuppression as initial therapy for

posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Transplant.

11:336–347. 2011.

|

|

16

|

Parker A, Bowles K, Bradley JA, et al:

Haemato-oncology Task Force of the British Committee for Standards

in Haematology and British Transplantation Society: Management of

post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in adult solid organ

transplant recipients - BCSH and BTS Guidelines. Br J Haematol.

149:693–705. 2010.

|

|

17

|

Svoboda J, Kotloff R and Tsai DE:

Management of patients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative

disorder: the role of rituximab. Transpl Int. 19:259–269. 2006.

|

|

18

|

Trappe R, Oertel S, Leblond V, et al;

German PTLD Study Group; European PTLD Network. Sequential

treatment with rituximab followed by CHOP chemotherapy in adult

B-cell post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD): the

prospective international multicentre phase 2 PTLD-1 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 13:196–206. 2012.

|

|

19

|

Trappe R, Hinrichs C, Appel U, et al:

Treatment of PTLD with rituximab and CHOP reduces the risk of renal

graft impairment after reduction of immunosuppression. Am J

Transplant. 9:2331–2337. 2009.

|

|

20

|

Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Usiekniewicz J, et

al: Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder of the lung in a

renal transplant recipient treated successfully with surgery.

Transplant Proc. 38:173–176. 2006.

|

|

21

|

Moudouni SM, Tligui M, Doublet JD, Haab F,

Gattegno B and Thibault P: Lymphoproliferative disorder presenting

as a tumor of the renal allograft. Int Urol Nephrol. 38:779–782.

2006.

|

|

22

|

André N, Roquelaure B and Conrath J:

Molecular effects of cyclosporine and oncogenesis: a new model. Med

Hypotheses. 63:647–652. 2004.

|

|

23

|

Pascual J: Post-transplant

lymphoproliferative disorder - the potential of proliferation

signal inhibitors. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 22(Suppl 1): i27–i35.

2007.

|

|

24

|

Alexandru S, Gonzalez E, Grande C, et al:

Monotherapy rapamycin in renal transplant recipients with lymphoma

successfully treated with rituximab. Transplant Proc. 41:2435–2437.

2009.

|

|

25

|

DiNardo CD and Tsai DE: Treatment advances

in posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease. Curr Opin Hematol.

17:368–374. 2010.

|