Introduction

As the paratesticular region contains various

structures, including the epididymis, spermatic cord, tunica

vaginalis and strong fat-ligament-muscle supporting tissues, it may

give rise to a number tumor types with various behaviors (1). Tumor variability may also be due to

the Wolffian duct origin of the testis appendages, including the

spermatic cord. The most significant feature of the paratesticular

region is that it is the origin of a small number of tumors with

rich diversity.

The majority of the masses within the scrotum in

adults are of testicular origin. Paratesticular masses account for

2–3% and sarcomas account for ~30% of all scrotal masses (1–4). The

most common type of sarcoma is liposarcoma, followed by

leiomyosarcoma (LMS), rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), undifferentiated

pleomorphic sarcoma and fibrosarcoma (1–6). To

the best of our knowledge, only one instance of low-grade

fibromyxoid sarcoma in a paratesticular location has been

previously reported (7).

Determining the association between the

paratesticular mass and the testicle, and differentiation between

benign and malignant masses using radiology is challenging,

therefore the lesions are usually considered to be malignant and

radical orchiectomy with high ligation is used. The prognosis is

often poor, as recurrence and metastasis are common, and the

mechanism and outcome of regional lymph node resection,

radiotherapy and chemotherapy is unclear. The present study reports

seven cases of paratesticular sarcoma and emphasizes the

significant clinical and histological features.

Case reports

Seven cases of paratesticular sarcoma diagnosed at

the Pathology Department of the Istanbul Education and Research

Hospital (Istanbul, Turkey) are retrospectively investigated.

Hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining of the cases

were reevaluated and accurately diagnosed according to the recent

World Health Organization classification (8). The clinical information of the

patients was obtained from the patient files. Written informed

consent was obtained from all patients. All patients had been

referred to the Urology clinic at Istanbul Education and Research

Hospital with a growing scrotal mass. Excisional biopsy and simple

orchiectomy were performed in cases three and four and the two

patients were subsequently diagnosed with fibromyxoid sarcoma.

Radical orchiectomy was performed in the other five cases. Cases

one, two and three did not receive any additional treatment,

whereas chemotherapy and radiotherapy was adminstered to case five.

In cases four, six and seven, re-excision was performed due to

recurrence, and chemotherapy and radiotherapy were adminsitered

following re-excision.

The clinical features are summarized in Table I. The macroscopic and histological

characteristics of the cases were as follows: The lesions in cases

one and two consisted of large yellow (lipomatous) and

well-delineated areas, with occasional tan-gray colored

(leiomyosarcomatous) areas. The diameter of the leiomyosarcomatous

area was 8 cm in case one and 5 cm in case two. In addition, a few

gray-colored nodules, the largest with a 1 cm diameter, were

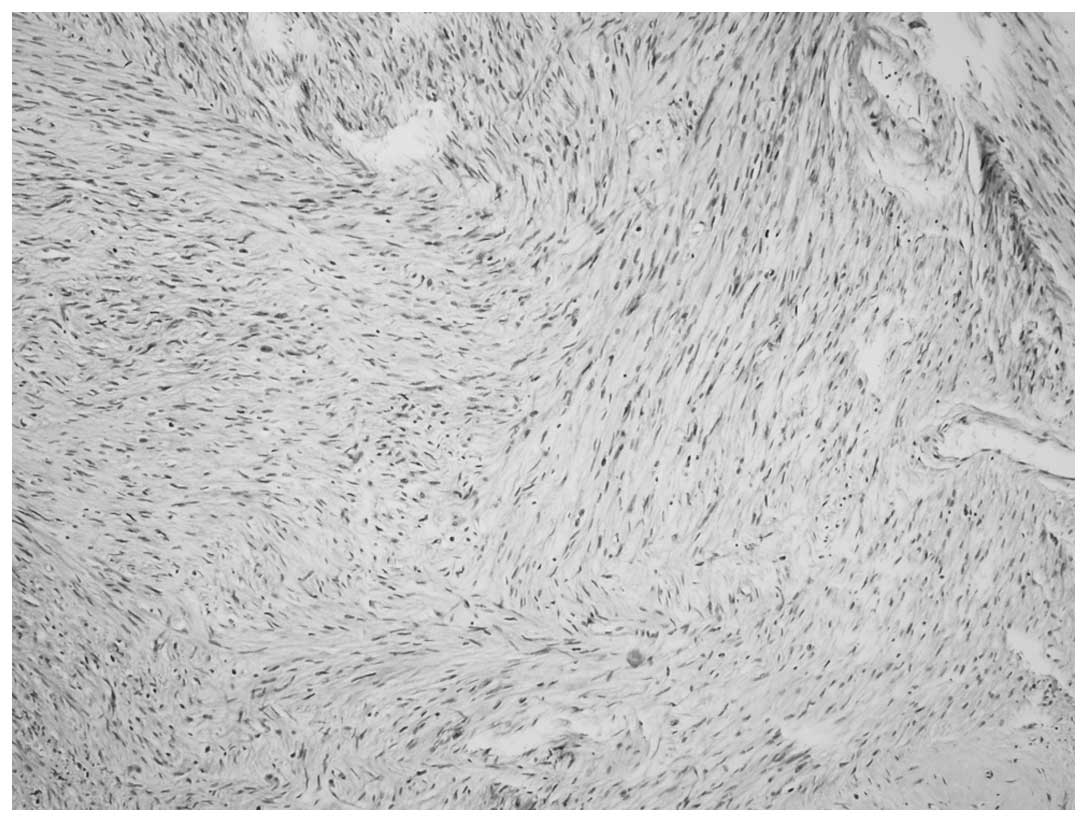

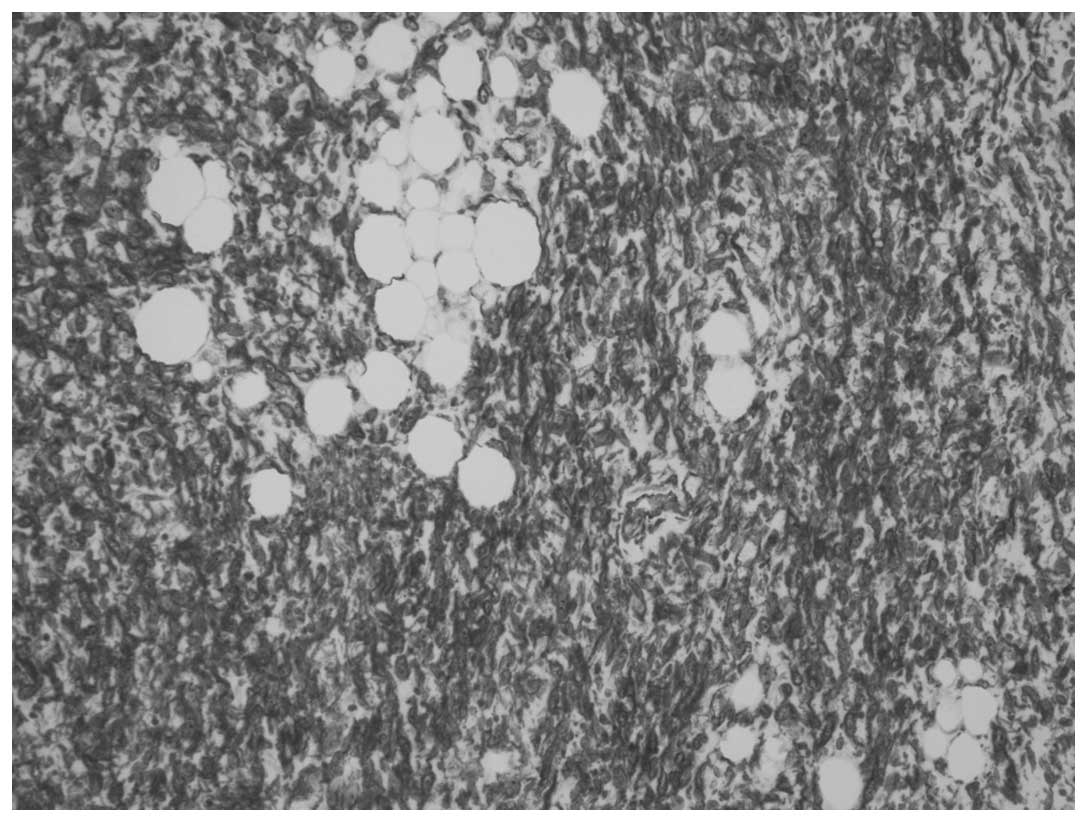

present in case two. A homologous pattern consisting of

well-differentiated liposarcoma, comprising predominantly spindle

cells, was present in each case (Fig.

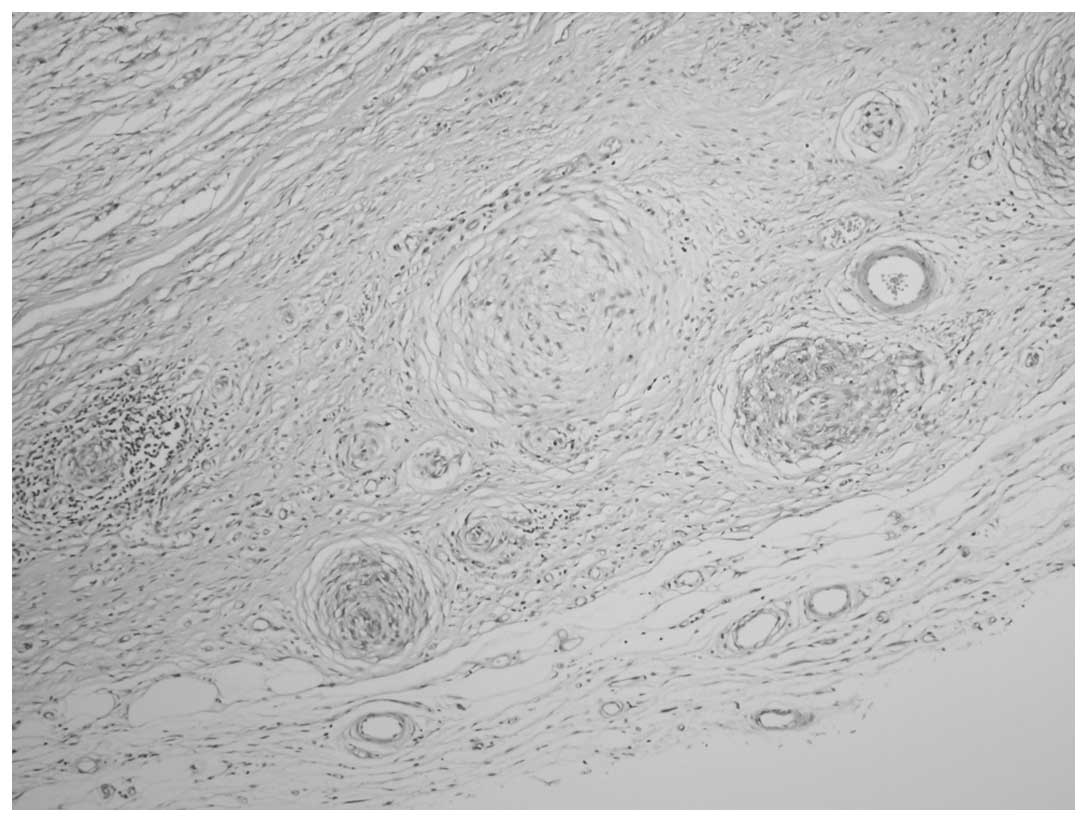

1). The heterologous pattern consisted of a LMS and

meningothelial-like whorl component in each case and a low-grade

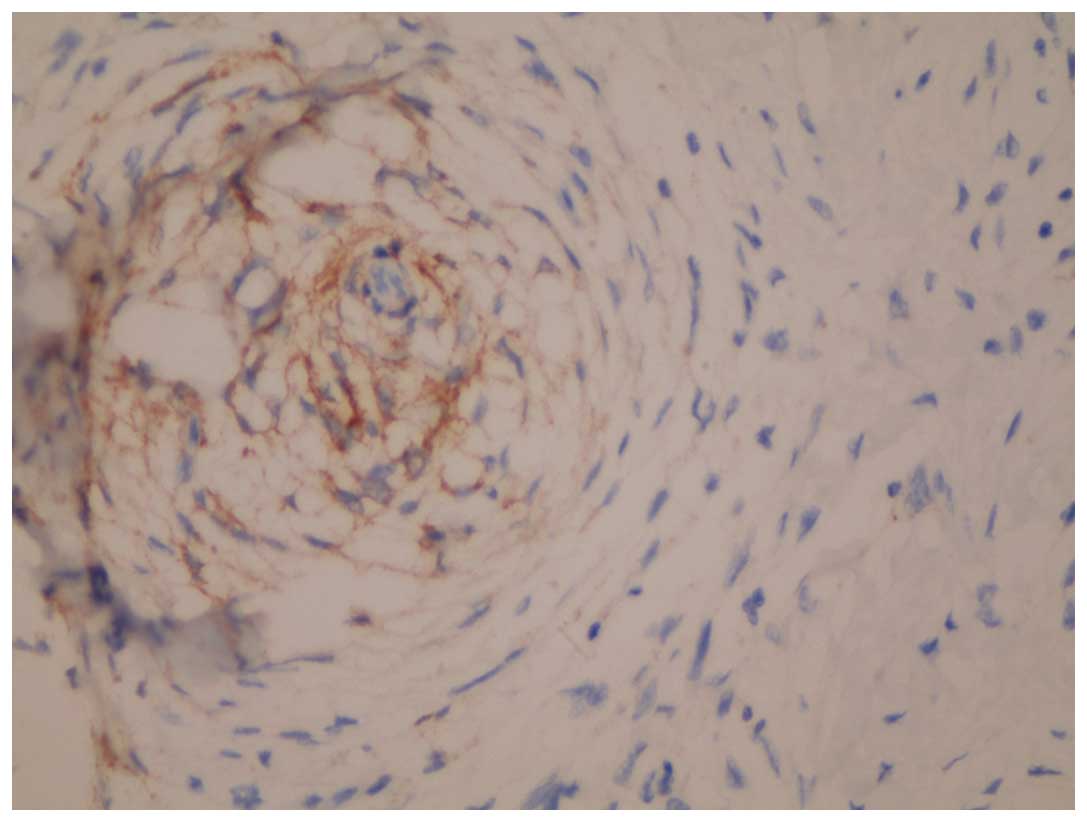

chondrosarcoma component in case one was also present (Figs. 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical staining of the

cells revealed that the whorl pattern area was positive for

epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; Fig.

4). A strong positive result for cluster of differentiation

(CD)34 was observed in the spindle cells within the spindle cell

liposarcoma areas, regarded as the homologous component (Fig. 5). The two cases were diagnosed as

leiomyosarcomatosis and dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLS)

containing whorl-pattern areas.

| Table IClinical findings and diagnosis of

paratesticular sarcoma. |

Table I

Clinical findings and diagnosis of

paratesticular sarcoma.

| Case | Age, years | Diagnosis | Tumor size, cm | Treatment | Additional

treatment | Follow-up time,

months | Disease outcome |

|---|

| 1 | 70 | Dedifferentiated

liposarcoma | 13.0 | Radical orchiectomy

with high cord ligation | None | 14 | Survival |

| 2 | 38 | Dedifferentiated

liposarcoma | 13.0 | Radical orchiectomy

with high cord ligation | None | 8 | Survival |

| 3 | 72 | Fibromyxoid

sarcoma | 7.0 | Excisional

biopsy | None | 22 | Mortality |

| 4 | 63 | Fibromyxoid

sarcoma | 9.0 | Simple

orchiectomy | Re-resection, CTh +

RTh | 43 | Mortality, recurrence

with lung metastasis |

| 5 | 64 | Leiomyosarcoma | 6.5 | Radical orchiectomy

with high cord ligation | CTh + RTh | 21 | Mortality, recurrence

with lung metastasis |

| 6 | 68 | Leiomyosarcoma | 7.4 | Radical orchiectomy

with high cord ligation | Re-resection, CTh +

RTh | 18 | Survival,

recurrence |

| 7 | 46 | Undifferentiated

pleomorphic sarcoma | 4.2 | Radical orchiectomy

with high cord ligation | Re-resection, CTh +

RTh | 44 | Mortality,

recurrence |

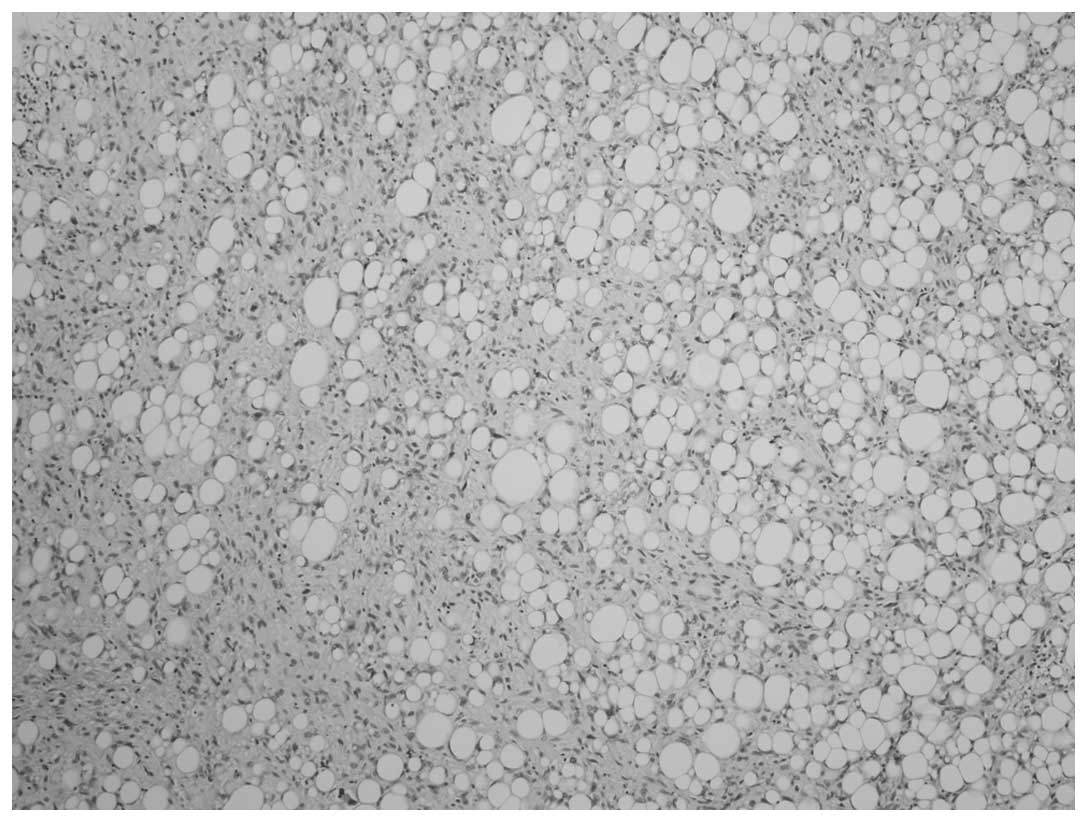

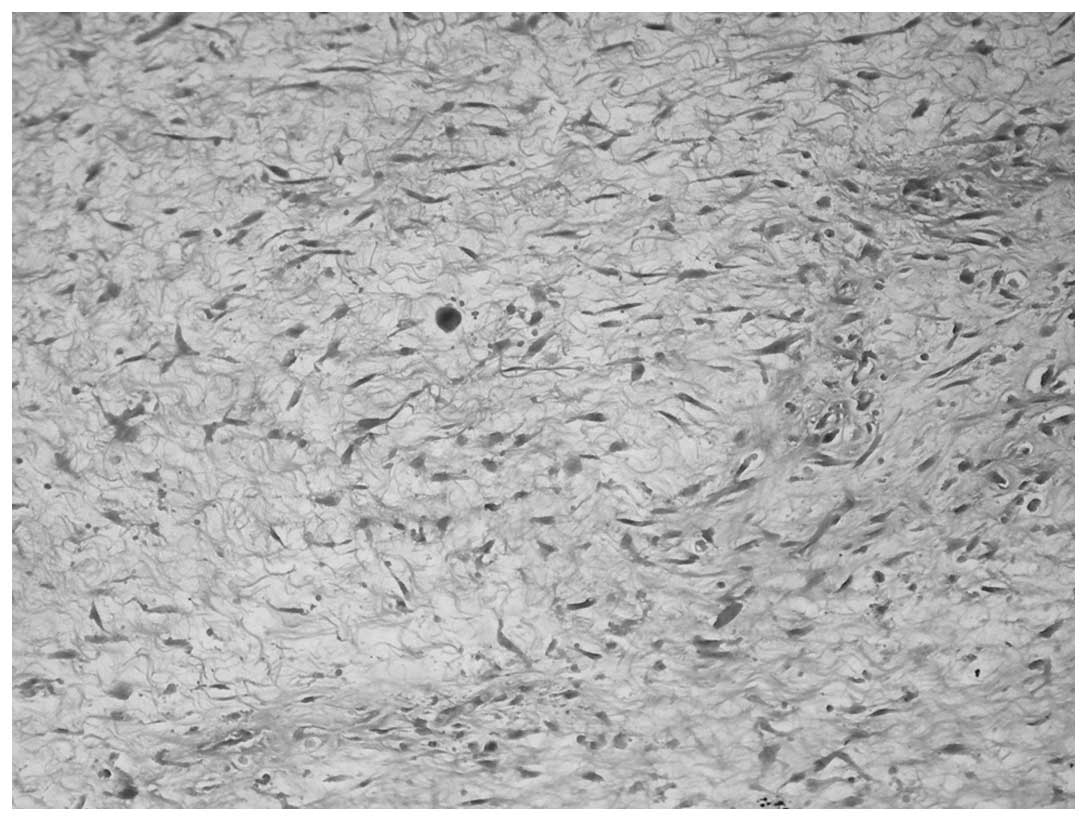

Cases three and four exhibited nodular,

well-delineated tumors with surgical border invasion. Microscopy

revealed the histology to be similar in the two cases, with the

prominent features consisting of a collagen and myxoid zone, mixed

with bland spindle-like fibroblastic cells and a whorl pattern, and

arcades of curvilinear blood vessels (Figs. 6 and 7). The cellularity of the tumors varied

from extremely low to moderate. Pleomorphism and mitosis were

present in the nuclei in a focal area in case four (Fig. 8). Immunohistochemical staining for

vimentin and MUC4 yielded a positive result in the two cases,

together with focal CD34 and EMA positivity. The patients were

diagnosed with low-grade fibomyxoid sarcoma.

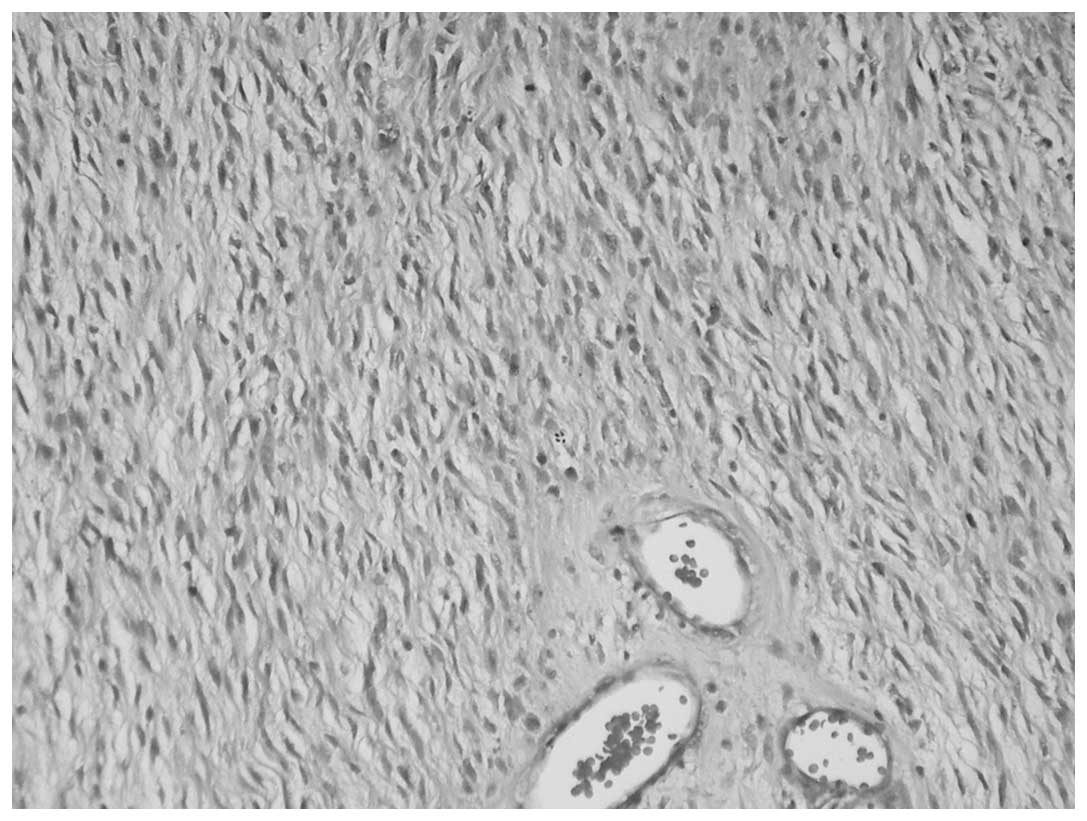

The masses in cases five and six were

well-circumscribed and nodular, with long bundles that were

parallel or perpendicular to each other. The cell cytoplasm was

strongly eosinophilic and the nuclei were generally spindle shaped,

with one blunt end. Mitosis was not frequent, with 1–3 mitoses per

10 high power fields. Necrosis was observed in focal areas and

pleomorphism was moderate. Immunohistochemical staining for smooth

muscle actin and desmin yielded a positive result. The two cases

were diagnosed as LMS.

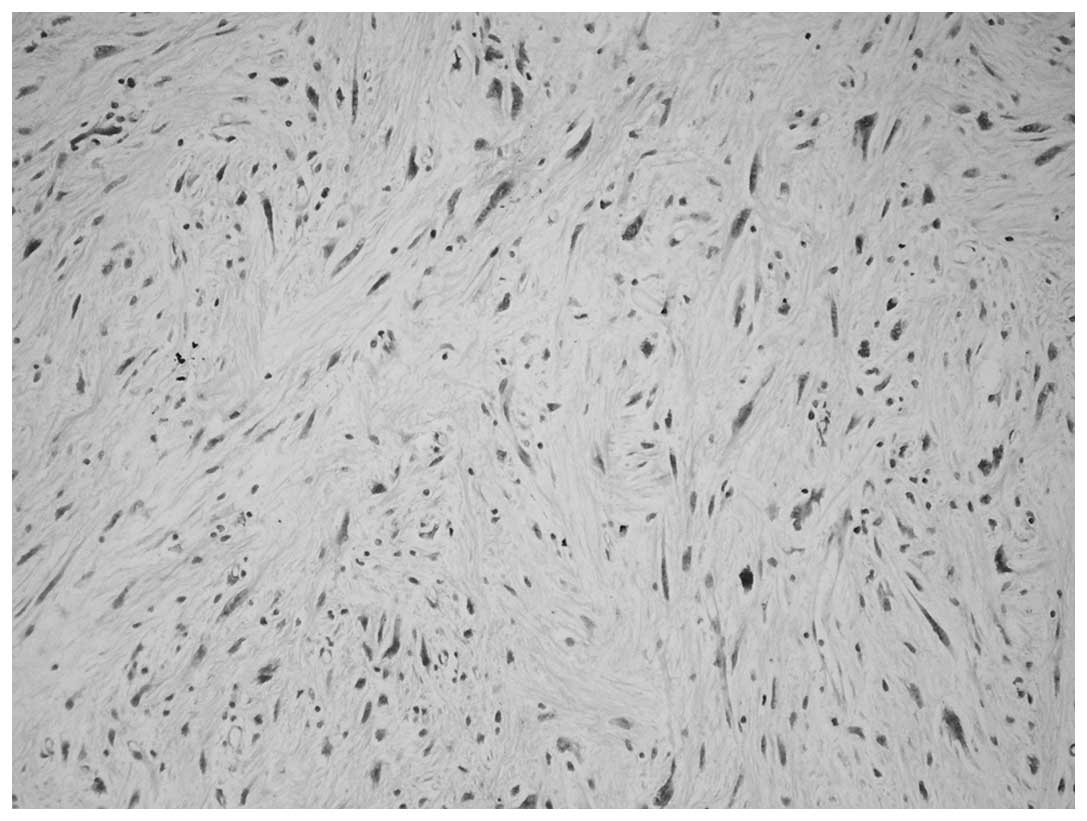

Macroscopically, the mass in case seven had

infiltrative borders, and, microscopically, was rich in spindle

cells, with small bundles and storiform patterns. The tissue also

contained large pleomorphic cells, with large eosinophilic

cytoplasm in certain areas. Immunohistochemical staining yielded a

positive result for vimentin only. This case was diagnosed as

undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Discussion

Paratesticular sarcomas are rare and account for ~2%

of all soft tissue sarcomas (9,10). No

clear approach is available regarding their behavior and treatment

due to their rarity. Liposarcoma and LMS are the most common

sarcomas (1–6). RMS is more frequent in younger

patients (6). The development of

various paratesticular neoplasia is due to the differing complex

structures in the region. In addition, embryological development of

the spermatic cord, the most common tumor localization, and the

other testicular adnexal structures from the Wolffian duct may be

responsible for this histological diversity.

The histological features of the three cases

diagnosed with LMS and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma were

typical and created no diagnostic problems. However, the two DDLS

cases exhibited extremely rare histological features.

Although the LMS and whorl patterns observed in the

DDLS cases is not common, they have been described in previous

studies (11–13). Leiomyosarcomatous areas were

observed in each of the DDLS cases. The cases exhibited low-grade

morphology and extremely low rates of mitosis, with mild

pleomorphism in focal areas. The positive immunohistochemical

staining for EMA in the whorl pattern areas was noteworthy and

suggested perineural or meningeal differentiation. Meningothelial

whorl-like morphology is less frequently observed than LMS. EMA was

present in each case and, to the best of our knowledge, these are

the first DDLS cases positive for EMA to be reported.

A further feature of the DDLS cases was the dominant

spindle cell liposarcoma as a homologous component. The

denomination of spindle cell liposarcoma remains controversial;

certain authors use spindle-cell neoplasm or spindle cell

lipoma-like neoplasm (14), and the

recommended name for certain lesions was fibrosarcoma-like lipoid

neoplasm, as determined in a report published by Deylup et

al (15). The authors who

recommend these names do not classify these tumors as liposarcoma,

however, lipoblasts were observed. The two DDLS cases in the

present study were rich in spindle cell lipoma-like (spindle cell

liposarcoma) areas with strong cytoplasmic CD34-positivity, as well

as rich in lipoblasts. These areas, which were the homologous

component for DDLS, should be classified as spindle cell

liposarcoma.

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma is a relatively rare

sarcoma (16–17). The upper extremities and the torso

are the most frequent locations, however, no paratesticular

localization has been previously reported. Low-grade fibromyxoid

sarcoma usually exhibits variable microscopic findings, with bland

fibroblasts, whorls, linear sequencing and less cellular myxoid

sections in certain areas (16).

Mitosis and necrosis are rare. One of the present cases exhibited

typical features of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, while case four

exhibited pleomorphism in focal areas that were also rich in

mitoses.

The accepted treatment for paratesticular masses is

radical inguinal orchiectomy, including the surrounding soft

tissues. No consensus with regard to regional lymph node excision

has been reached, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In the current

study, radical orchiectomy with high ligation was performed for the

seven cases. Simple orchiectomy and excisional biopsy were

conducted for the two cases with fibromyxoid sarcoma. The two

patients with fibromyxoid sarcoma succumbed to the disease within

22 and 43 months, respectively, as there was residual mass and the

patients did not accept additional treatment. This emphasizes the

importance of radical surgical treatments. No recurrence or

metastasis was observed in the two cases of liposarcoma and the

improved prognosis of liposarcoma compared with the other sarcomas,

or the short clinical follow-up durations may have had an effect on

this finding. As four of the seven cases succumbed to the disease

and one remains alive with the sarcoma demonstrates the requirement

for a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of paratesticular

sarcomas.

In conclusion, the paratesticular region consists of

complex structures that can develop various neoplastic formations

and patterns. Sarcomas comprise a significant part of

paratesticular masses and may exhibit an aggressive clinical

course. In older patients, paratesticular sarcomas must be

considered for the differential diagnosis of scrotal masses, which

do not exhibit a clear association with the testes. Furthermore,

clinicians and patients must be informed about the high probability

of local recurrence and distant metastasis in paratesticular

sarcomas.

References

|

1

|

Lioe TF and Biggart JD: Tumours of the

spermatic cord and paratesticular tissue. A clinicopathological

study. Br J Urol. 71:600–606. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Varzaneh FE, Verghese M and Shmookler BM:

Paratesticular leiomyosarcoma in an elderly man. Urology.

60:11122002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sogani PC, Grabstald H and Whitmore WF Jr:

Spermatic cord sarcoma in adults. J Urol. 120:301–305.

1978.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Russo P, Brady MS, Conlon K, Hajdu SI,

Fair WR, Herr HW and Brennan MF: Adult urological sarcoma. J Urol.

147:1032–1036. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Khoubehi B, Mishra V, Ali M, Motiwala H

and Karim O: Adult paratesticular tumours. BJU Int. 90:707–715.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Soosay GN, Parkinson MC, Paradinas J and

Fisher C: Paratesticular sarcomas revisited: a review of cases in

the British Testicular Tumour Panel and Registry. Br J Urol.

77:143–146. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hansen T, Katenkamp K, Brodhun M and

Katenkamp D: Low-grade fibrosarcoma - report on 39 not otherwise

specified cases and comparison with defined low-grade fibrosarcoma

types. Histopathology. 49:152–160. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW

and Mertens F: WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and

Bone. 5. 4th edition. IARC Press; Lyon: 2013

|

|

9

|

Stojadinovic A, Leung DH, Allen P, Lewis

JJ, Jaques DP and Brennan MF: Primary adult soft tissue sarcoma:

time-dependent influence of prognostic variables. J Clin Oncol.

20:4344–4352. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dotan ZA, Tal R, Golijanin D, Snyder ME,

Antonescu C, Brennan MF and Russo P: Adult genitourinary sarcoma:

the 25-year Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. J Urol.

176:2033–2038. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pilotti S and Pierotti MA:

Well-differentiated liposarcoma with leiomyomatous differentiation.

Am J Surg Pathol. 26:1643–1644. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Henricks WH, Chu YC, Goldblum JR and Weiss

SW: Dedifferentiated liposarcoma: a clinicopathological analysis of

155 cases with a proposal for an expanded definition of

dedifferentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 21:271–281. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fanburg-Smith JC and Miettinen M:

Liposarcoma with meningothelial-like whorls: a study of 17 cases of

a distinctive histological pattern associated with dedifferentiated

liposarcoma. Histopathology. 33:414–424. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mentzel T, Palmedo G and Kuhnen C:

Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma (‘atypical spindle

cell lipomatous tumor’) does not belong to the spectrum of atypical

lipomatous tumor but has a close relationship to spindle cell

lipoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular

analysis of six cases. Mod Pathol. 23:729–736. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Deyrup AT, Chibon F, Guillou L, Lagarde P,

Coindre JM and Weiss SW: Fibrosarcoma-like lipomatous neoplasm: a

reappraisal of so-called spindle cell liposarcoma defining a unique

lipomatous tumor unrelated to other liposarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol.

37:1373–1378. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Vernon SE and Bejarano PA: Low-grade

fibromyxoid sarcoma: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

130:1358–1360. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Folpe AL, Lane KL, Paull G and Weiss SW:

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor

with giant rosettes: a clinicopathologic study of 73 cases

supporting their identity and assessing the impact of high-grade

areas. Am J Surg Pathol. 24:1353–1360. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|