Introduction

Osteomas are benign neoplasms consisting of mature

normal osseous tissue (1). Osteomas

of the head often arise from the periosteum of the skull, sinuses

and mandible (1). Intracranial

osteomas are rare, and usually arise from the inner table of the

skull (1). Intracranial osteomas

completely unrelated to osseous tissues are extremely rare, and are

classified into intraparenchymal osteomas and dural osteomas

(1). Despite a series of 10 autopsy

cases of dural osteomas, the clinical features and surgical

strategy remain unclear (2). The

present report describes a rare surgical case of intracranial

osteoma arising from the falx, and discusses the clinical features,

intraoperative findings and management strategy of this

disease.

Case report

In March 2014, a 40-year-old female was admitted to

Teishinkai Hospital (Hokkaido, Japan) due to persistent headache.

On admission, neurological examination revealed no abnormalities.

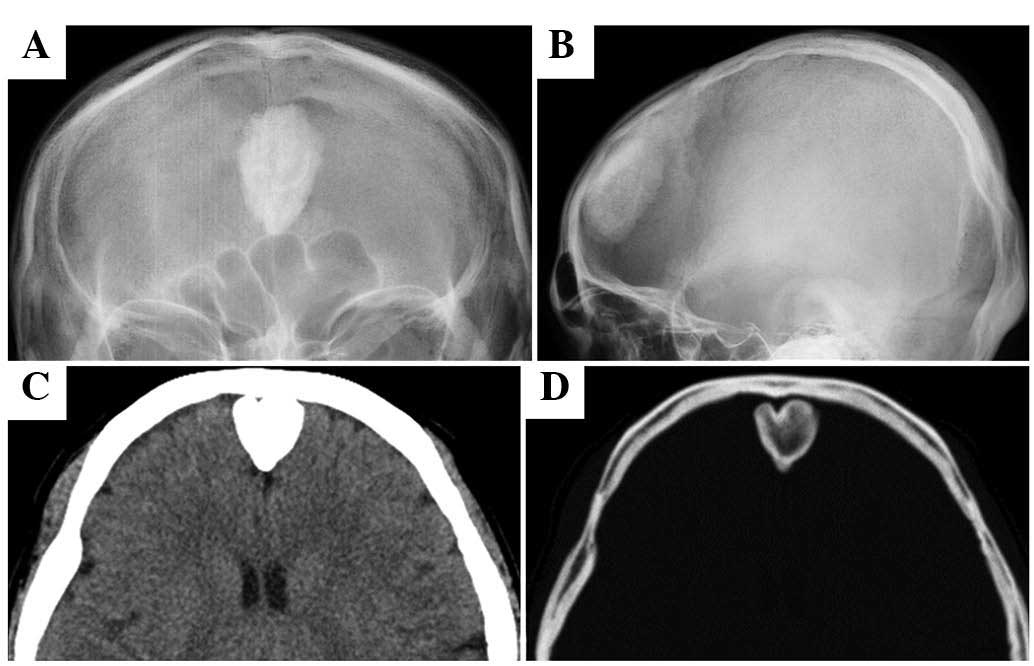

Skull radiography revealed a radiopaque lesion in the frontal area

(Fig. 1A and B), while computed

tomography (CT) and bone window CT revealed an ossified lesion in

the frontal area (Fig. 1C and D).

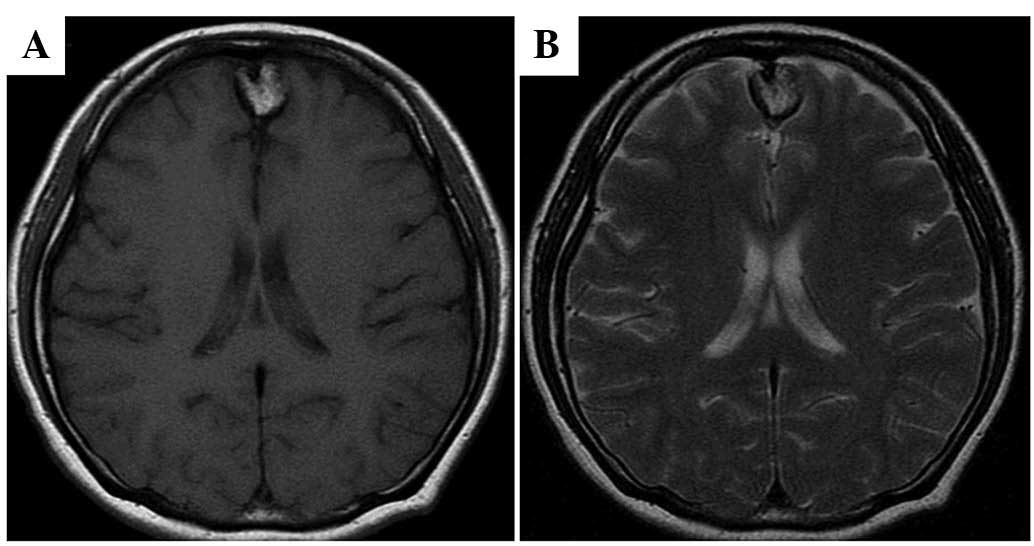

Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a mass appearing as

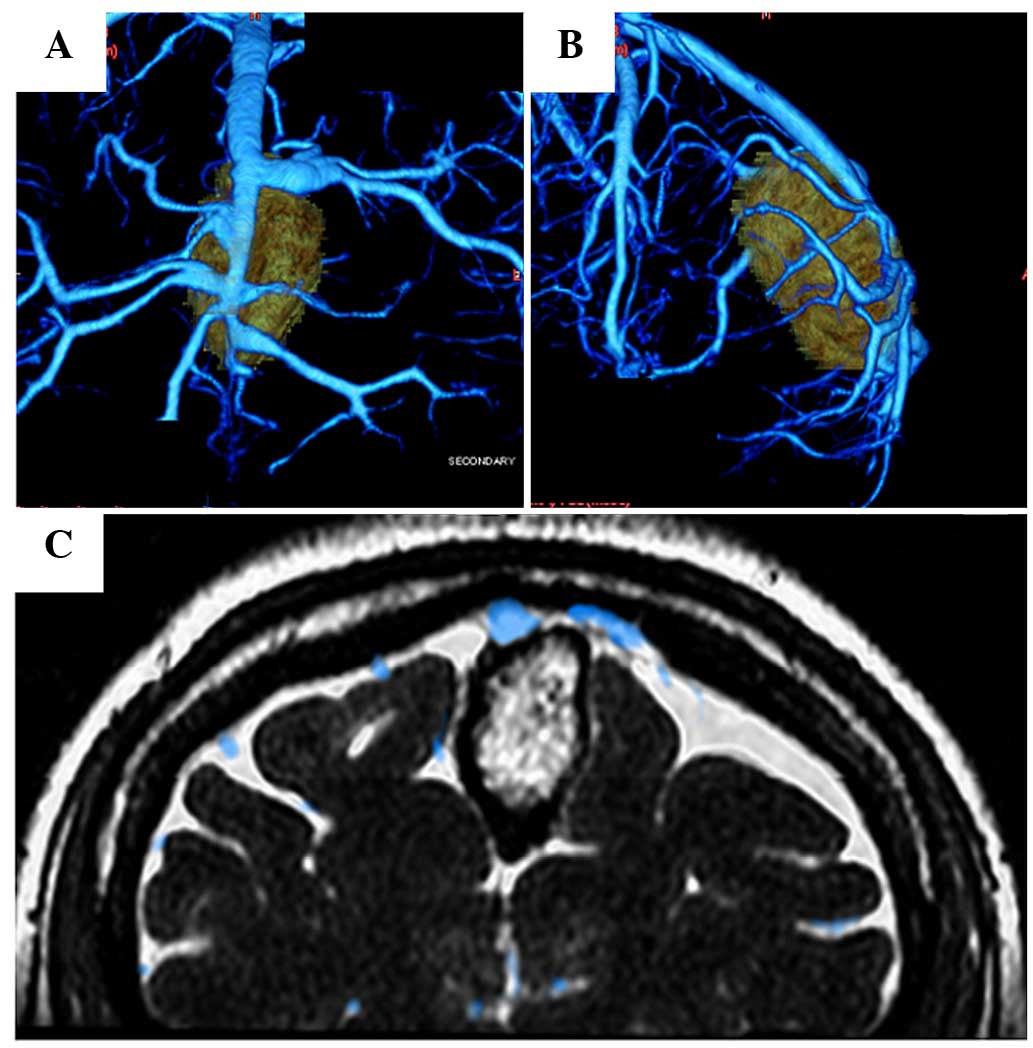

hyperintense on both T1- and T2-weighted images (Fig. 2). Three-dimensional CT venography

(Fig. 3A and B) and fast imaging

employing steady-state acquisition (FIESTA)/CT venography fusion

imaging (Fig. 3C) demonstrated that

the mass was located just below the superior sagittal sinus and

cortical veins, and had adhered partially to these veins. The

provisional diagnosis was calcified falx meningioma or osteoma

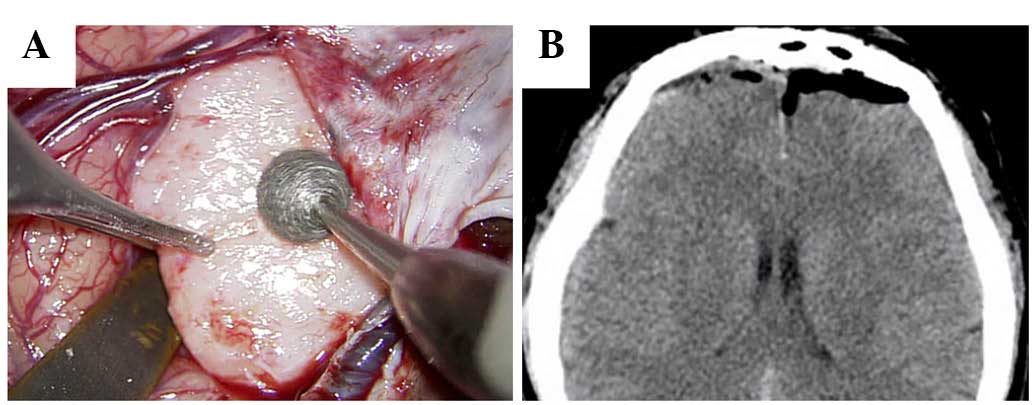

originating from the falx. Bilateral frontal craniotomy was

performed. Opening of the dura revealed that the mass was attached

to the falx in the mesial frontal lobes extra-axially, without

dural attachment. The hard bony mass was removed with a drill and a

rongeur (Fig. 4A). The cortical veins

and superior sagittal sinus were preserved completely.

Postoperative CT demonstrated complete tumor resection without

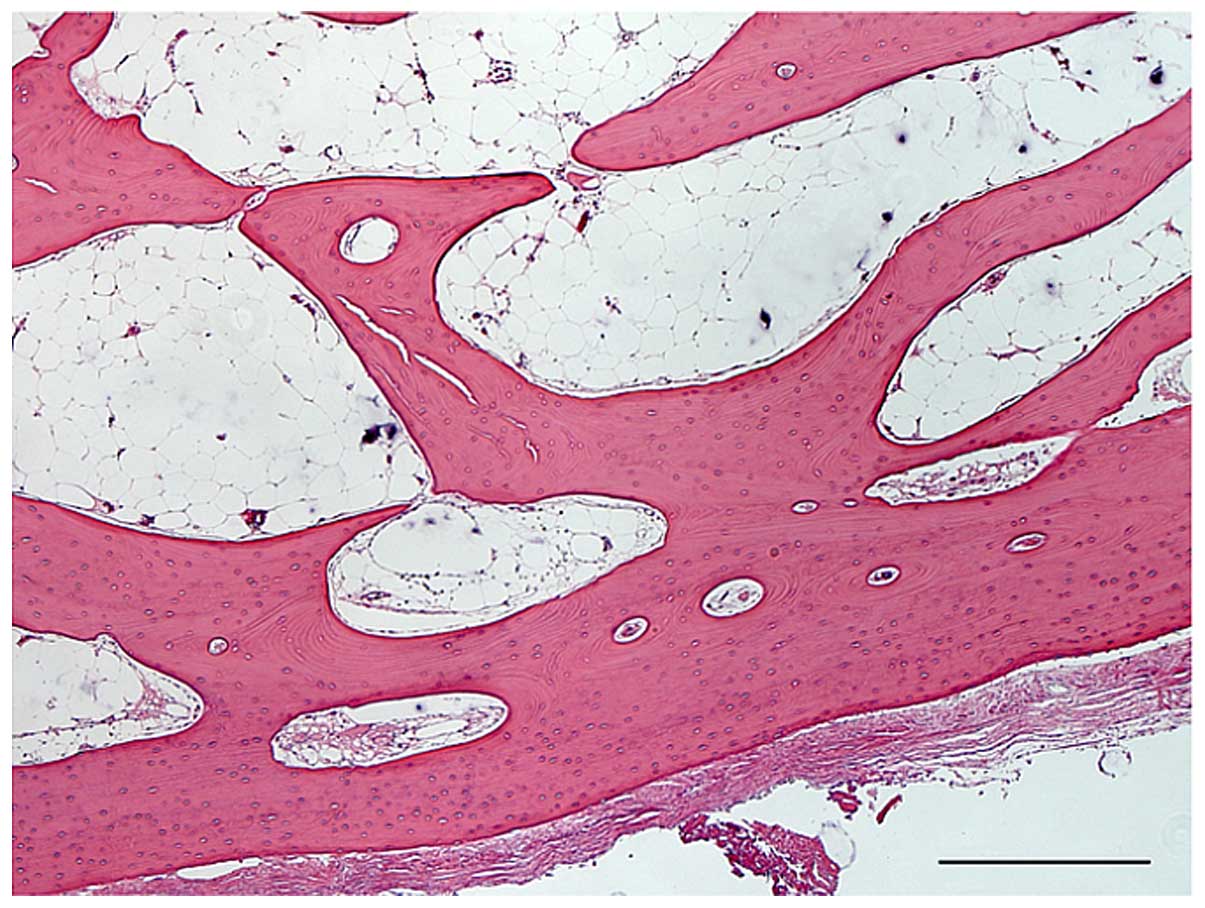

complication (Fig. 4B). Histological

examination (hematoxylin and eosin staining) revealed lamellated

bony trabeculae lined with osteoblasts, and the intertrabecular

marrow spaces occupied by adipose tissue. These findings are

compatible with osteoma (Fig. 5). The

postoperative course was uneventful, and the symptoms disappeared

after surgery. The patient was discharged 12 days after surgery

without neurological deficit. The patient was followed up for 12

months without any recurrence.

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of the present case report and any

accompanying images.

Discussion

Intracranial osteomas are rare, with only 12

surgical cases of osteomas without association with the bone being

reported in the literature so far, including the present case, as

summarized in Table I (3–13). The

male to female ratio was 1:2, and the age of the patients was 16–64

years (mean, 39.8 years). The most common symptom was headache,

which occurred in 8 of the 12 cases. The tumors were described as

‘completely surrounded by cerebral tissue’, with ‘no connections

with the dura or the skull’, or ‘covered with the arachnoid

membrane’ in 5 cases. The tumors were attached to the inner dural

surface in 5 cases, and to the falx in 2 cases, indicating dural

osteomas. Therefore, the present case is the second surgical case

of intracranial osteoma originated from the falx. The outcome was

good in 10 patients, whereas 1 patient succumbed to disease. Venous

infarction developed in 1 case (10).

| Table I.Surgical cases of intracranial osteoma

without connections with the skull. |

Table I.

Surgical cases of intracranial osteoma

without connections with the skull.

| Author (year)

(ref) | Age,

years/gender | Symptom | Location | Size | Surgical finding | Outcome |

|---|

| Vakaet et al

(1983) (3) | 16/F | Headache,

seizure | Frontal

inter-callosum | 5.0×5.0×6.0

cm3 | Completely surrounded

by cerebral tissue | Dead (postoperative

hemorrhage) |

| Choudhury et

al (1995) (4) | 20/F | Headache | Right frontal

convexity | 1.0 cm in

diameter | Attached to the inner

dural surface | Good |

| Lee and Lui (1997)

(5) | 28/F | Headache | Left frontal

convexity | 4.0×2.5×0.5

cm3 | Covered with

arachnoid membrane | Good |

| Aoki et al

(1998) (6) | 51/F | Headache | Right frontal

convexity | 1.1×1.5×0.7

cm3 | Partially adherent to

the inner dural surface | Good |

| Sugimoto et al

(2001) (7) | 35/M | Vertigo | Right frontal

convexity | 5.0×5.0×2.0

cm3 | Attached to the inner

dural surface | Not described |

| Cheon et al

(2002) (8) | 43/F | Headache | Left frontal

convexity | 1.2×2.0×0.7

cm3 | Attached to the inner

dural surface | Good |

| Pau et al

(2003) (9) | 33/F | None | Left frontal

convexity | 3.0×2.0×2.0

cm3 | No connections with

the dura | Good |

| Akiyama et al

(2005) (10) | 24/M | Headache | Right frontal

convexity | Not described

(multiple) | Covered with

arachnoid membrane | Good (venous

infarction) |

| Jung et al

(2007) (11) | 60/M | Headache | Right frontal

convexity | Not described | Attached to the inner

dural surface | Good |

| Barajas et al

(2012) (12) | 63/F | Altered mental

status | Right middle cranial

fossa | 4.5×3.7×2.5

cm3 | No connections with

the dura | Good |

| Chen et al

(2013) (13) | 64/M | Tinnitus,

dizziness | Right mesial frontal

lobe | 2.5×2.0×2.0

cm3 | Attached to the

falx | Good |

| Present case

(2016) | 40/F | Headache | Interhemispheric

space | 2.2×1.7×2.5

cm3 | Attached to the

falx | Good |

Intracranial osteoma usually has a wide base and

grows inward as an expanding mass with a well-defined border

(4). The present case occurred as a

nodule with a narrow neck attached to the falx, similar to a

previous case (13). The pathogenesis

of osteoma without bone involvement is still unknown. In the

present case, new bone generation from the falx is a possible

cause, since the meninges may function as the periosteum of the

inner table of the skull (2,5,8). A history

of head trauma has been noted in patients with intracranial

osteomas. Therefore, head trauma may be one of the trigger

mechanisms of intracranial osteoma (14); however, the present patient had no

such history.

No standardized treatment algorithm has been

established for this condition. If the patient is asymptomatic,

conservative therapy is one of the choices, since the natural

history of intracranial osteomas is more benign than that of

osteomas of the frontal sinuses (3).

The present patient complained of intractable headache, which could

be resolved by surgical tumor removal, since such pain is

considered to be due to irritation and compression of the adjacent

dural membrane (10). Therefore,

surgery was performed in the present case, and the pain disappeared

completely.

Surgeons should pay particular attention to possible

adhesion of intracranial osteoma to the blood vessels. In a

previous case, the osteoma had adhered tightly to the superficial

cortical veins, which were sacrificed, thus leading to

postoperative venous congestion (10). In the present case, preoperative

FIESTA/CT venography fusion imaging was very useful to demonstrate

that the mass was located just below the superior sagittal sinus

and cortical veins, and had adhered partially to these veins.

Complete preservation of these structures was carefully achieved

during surgery. Reconstruction via saphenous vein graft and patch

is recommended if the superior sagittal sinus or cortical vein is

injured (15,16).

In conclusion, the present case of intracranial

osteoma originating from the falx was successfully treated

surgically. Preoperative FIESTA/CT venography fusion imaging was

very useful to demonstrate adhesion between the mass and the

superior sagittal sinus and cortical veins.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

FIESTA

|

fast imaging employing steady-state

acquisition

|

References

|

1

|

Haddad FS, Haddad GF and Zaatari G:

Cranial osteomas: Their classification and management. Report on a

giant osteoma and review of the literature. Surg Neurol.

48:143–147. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fallon MD, Ellerbrake D and Teitelbaum SL:

Meningeal osteomas and chronic renal failure. Hum Pathol.

13:449–453. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Vakaet A, De Reuck J, Thiery E and vander

Eecken H: Intracerebral osteoma: A clinicopathologic and

neuropsychologic case study. Childs Brain. 10:281–285.

1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Choudhury AR, Haleem A and Tjan GT:

Solitary intradural intracranial osteoma. Br J Neurosurg.

9:557–559. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee ST and Lui TN: Intracerebral osteoma:

Case report. Br J Neurosurg. 11:250–252. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Aoki H, Nakase H and Sakaki T: Subdural

osteoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 140:727–728. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sugimoto K, Nakahara I, Nishikawa M,

Tanaka M, Terashima T, Yanagihara H and Hayashi J: Osteoma

originating in the dura: A case report. No Shinkei Geka.

29:993–996. 2001.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cheon JE, Kim JE and Yang HJ: CT and

pathologic findings of a case of subdural osteoma. Korean J Radiol.

3:211–213. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pau A, Chiaramonte G, Ghio G and Pisani R:

Solitary intracranial subdural osteoma: Case report and review of

the literature. Tumori. 89:96–98. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Akiyama M, Tanaka T, Hasegawa Y, Chiba S

and Abe T: Multiple intracranial subarachnoid osteomas. Acta

Neurochir (Wien). 147:1085–1089. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jung TY, Jung S, Jin SG, Jin YH, Kim IY

and Kang SS: Solitary intracranial subdural osteoma: Intraoperative

findings and primary anastomosis of an involved cortical vein. J

Clin Neurosci. 14:468–470. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Barajas RF Jr, Perry A, Sughrue M, Aghi M

and Cha S: Intracranial subdural osteoma: A rare benign tumor that

can be differentiated from other calcified intracranial lesions

utilizing MR imaging. J Neuroradiol. 39:263–266. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen SM, Chuang CC, Toh CH, Jung SM and

Lui TN: Solitary intracranial osteoma with attachment to the falx:

A case report. World J Surg Oncol. 11:2212013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dukes HT and Odom GL: Discrete intradural

osteoma. Report of a case. J Neurosurg. 19:251–253. 1962.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hakuba A, Huh CW, Tsujikawa S and

Nishimura S: Total removal of a parasagittal meningioma of the

posterior third of the sagittal sinus and its repair by autogenous

vein graft. Case report. J Neurosurg. 51:379–382. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Murata J, Sawamura Y, Saito H and Abe H:

Resection of a recurrent parasagittal meningioma with cortical vein

anastomosis: Technical note. Surg Neurol. 48:592–595; discussion

595–597. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|