Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common types of

gynecological malignancy and has a poor prognosis. Historically,

ovarian cancer was considered a silent cancer, as the majority of

patients present with late-stage disease (1). Despite advances in surgery and the

development of more effective chemotherapy, ovarian cancer remains

the leading cause of mortality from a gynecological cancer

(2). Drug resistance is the

predominant cause of mortality in late-stage patients. In total,

~30% of patients whose tumors are platinum-resistant will generally

either progress during primary therapy or shortly thereafter.

Additionally, there is no preferred standard second-line

chemotherapy to offer these patients (3,4). Thus,

elucidation of mechanisms and identification of new therapeutic

targets for ovarian cancer is critical to reduce fatality.

Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) show promise

as a novel class of anticancer agents in a wide spectrum of tumors,

including ovarian caner (5).

Previously, the present study investigated whether the HDACi

trichostatin A (TSA) induces apoptosis of ovarian cancer A2780

cells in a dose-dependent manner (6).

Thus far, numerous HDACis are being tested in over 100 clinical

trials and have exhibited encouraging therapeutic responses with

good safety profiles (7,8). The clinical potential of HDACis has been

well documented by the successful development of vorinostat

(suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid), which has been approved by the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (9). Despite the rapid progress achieved,

clinical data has shown that there is limited efficacy for HDACi as

a single agent. The majority of current clinical trials are

combination studies looking at HDACi in combination with other

agents (10,11). These combination trials seek to

increase the antitumor activity of the treatments. Although these

combination strategies follow a rational molecular approach in

certain cases, in the majority of instances, they are relatively

empirical. Accordingly, synergism in antitumor efficacy may be

accompanied by adverse effects that are rarely observed with HDACis

alone, such as severe myelosuppression (5,12).

Therefore, revealing the molecular mechanisms underlying the low

potency of HDACi is pivotal in determining the optimal application

of this class of therapeutic agents in the treatment of ovarian

cancer.

In our previous study, it was reported that the

adhesion molecule cluster of differentiation 146 (CD146) is

significantly induced in HDACi-treated tumor cells (13). In the current study, it was found that

the induction of CD146 expression was significant in ovarian cancer

cells. CD146 is one of the adhesion molecules belonging to the

immunoglobulin superfamily (14). In

numerous types of cancer, including melanoma (15), prostate cancer (16) and ovarian cancer, elevated expression

of CD146 promotes tumor progression and is associated with poor

prognosis. Previously, targeting CD146 with antibody against the

molecule has been shown to inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis in

several types of cancer. Based on these findings (15,17,18), the

present study chose to additionally explore whether the induced

expression of CD146 protected ovarian cancer cells from

HDACi-induced death. In addition, the current study tested whether

the antitumoral activity of HDACi may be significantly enhanced in

combination with the targeting of CD146 in ovarian cancer cells

in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

The human ovarian cancer cell lines A2780, SKOV3 and

Caov3 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection

(Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's

medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). All cells were cultured at

37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The HDACi TSA

and vorinostat were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Millipore,

Darmstadt, Germany), and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

The mouse anti-human CD146 monoclonal antibody (mAb) AA98 and the

control mIgG were provided by Dr Xiyun Yan (Institute of

Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China) (19). The mouse anti-human CD146 mAb (1

mg/ml; ab24577) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated mouse anti-human CD146 mAb

(1:100; 11-1469-42) was purchased from eBioscience, Inc. San Diego,

CA, USA). Anti protein kinase B (Akt) rabbit anti-human polyclonal

antibody (1:1,000; #9272S), anti-phosphorylated Akt rabbit

anti-human mAb (1:1,000; #4058), anti-human phosphorylated glycogen

synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) rabbit mAb, (1:1,000; #5558), anti-human

phosphorylated 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) rabbit mAb (1:1,000;

#2855) and anti-human phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 kinase-1

(S6K1) mouse mAbs (1:1,000; #9206) were purchased from Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Triciribine was

purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Full-length Akt2 complementary DNA (cDNA) was cloned into pcDNA3.1

plasmid and termed the AAkt2 vector, which has been described

previously (13).

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was determined using a MTT assay. In

brief, 5×103 cells were plated into each well of 96-well

plates for 72 h following the indicated treatments. Subsequently, 5

mg/ml MTT was added and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The medium was

then removed, and 1 ml DMSO was added to solubilize the

MTT-formazan product. The MTT absorbance was then determined at 570

nm on a Multiscan JX ver1.1 (Thermo Labsystems, Santa Rosa, CA,

USA). Results are expressed as a percentage of the viable cells in

the DMSO-treated group. Each data point is the mean ± standard

error of the mean of 6 replicates.

Apoptosis assays

Cells were stained with Annexin V and propidium

iodide and the percentage of apoptotic cells were determined by

flow cytometry, as described previously (20). CELL Quest software (BD Biosciences,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used for data acquisition and

analysis.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from A2780 or SKOV3 cells

after vorinostat treatment using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RNA quantitation was determined using a NanoDrop

micro-volume spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

and the messenger RNA (mRNA) integrity was verified by agarose gel

electrophoresis. Reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR was then performed

on 2 µg total RNA using a PrimeScript RT Reagent kit with gDNA

Eraser (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). qPCR was performed in ABI

Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

with the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore)

using the following thermocycler program for all genes: 5 min of

pre-incubation at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, 15

sec at 60°C, and 30 sec at 72°C. The primers for were as follows:

CD146 forward, 5′-CAGTCCTCATACCAGAGCCAACAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGACCAGGATGCACACAATCA-3′; and 18S ribosomal RNA forward,

5′-AGTCCCTGCCCTTTGACACA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GATCCGAGGGCCTCACTAAAC-3′. The 18S ribosomal RNA was used as an

internal control. All primers were obtained from Tiangen Biotech

Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). A melting curve assay was performed to

determine the purity of the amplified product. Contamination with

genomic DNA was not detected in any of the analyzed samples. Each

sample was assayed in triplicate, analysis of relative gene

expression data used the 2−ΔΔCq method, as previously

described (21), and the results were

expressed as fold induction compared with the untreated group.

Western blot analysis

Detection of the CD146, AKT, p-AKT, P-4E-BP1,

p-S6K1, p-GSK-3β and β-actin by SDS-PAGE was performed as

previously described (21).

Soft agar colony-forming assay

Cells were treated with 10 µg/ml AA98, 2.5 µmol/l

vorinostat or vorinostat + AA98 for 24 h. DMSO-treated cells were

used as a negative control. A total of 1×103 cells were

then plated in 60-mm culture plates in medium containing 0.3% agar

overlying a 0.5% agar layer. The cells were subsequently incubated

for 14 days at 37°C and colonies were stained with 0.5 ml of

0.0005% crystal violet solution for 1 h and counted using a

dissecting microscope (×50 magnification). The results are

expressed as a percentage of colonies in the DMSO-treated

group.

Animal experiments

In total, 120 female athymic BALB/c nude mice were

obtained from the Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Medical

Science (Beijing, China). The 6-week-old mice used were maintained

in a laminar-flow cabinet under specific pathogen free conditions.

In tumor xenograft models, 1×107 SKOV3 cells were

injected subcutaneously. Once tumors had grown between 5 and 6 mm,

the mice were grouped (n=10) and administered intraperitoneally

with 8 mg/kg of AA98 or 20 mg/kg of vorinostat or vorinostat + AA98

twice a week until the mice were sacrificed (tumor volume >1,000

mm3 or 42 days subsequent to treatment). PBS served as a

control. Tumor size was determined twice a week and tumor volume

was determined according to the equation: Tumor size

(cm3)=width2xlengthx(π/6).

Laser scanning cytometry (LSC)

LSC slides were scanned using an LSC instrument

equipped with argon (Ar; 488 nm) and helium-neon (HeNe; 633 nm)

laser and iCys3.3.4 software (CompuCyte; Beckman Coulter, Inc.,

Brea, CA, USA). DNA staining based on hematoxylin served as the

trigger/contouring parameter. The following channels and settings

were used for data collection: Argon green photomultiplier tube

(PMT, 15–25%; offset, 0.2; gain, 13%) and HeNe LongRed (LR; PMT,

14–22%; offset, 0–0.3; gain, 13%). The present study analyzed the

immunohistochemical tissue samples in phantom mode. Argon green and

HeNe LongRed parameters were collected with aberration

compensation. Statistical analysis was performed on the results of

3 independent experiments using the paired Student's t-test.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between

experimental and control groups was determined by one-way analysis

of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test using SPSS

software version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All

statistical tests were two sided, and P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical

analysis of LSC findings was performed on the results of 3

independent experiments using a paired Student's t test.

Results

Induction of adhesion molecular CD146

is a common phenomenon in vorinostat-treated ovarian cancer cells

in vitro and in vivo

In previous studies, adhesion molecule CD146 was

observed to be significantly upregulated following HDACi treatment

in ovarian cancer cells (13). In

addition, previous studies have linked CD146 with apoptosis

resistance in cancer cells (21,22). To

additionally verify whether expression of CD146 is induced by

vorinostat, the present study investigated the effects of

vorinostat on mRNA and protein expression of CD146 in ovarian

cancer cells. A2780 and SKOV3 cells were treated with 2.5 µmol/l

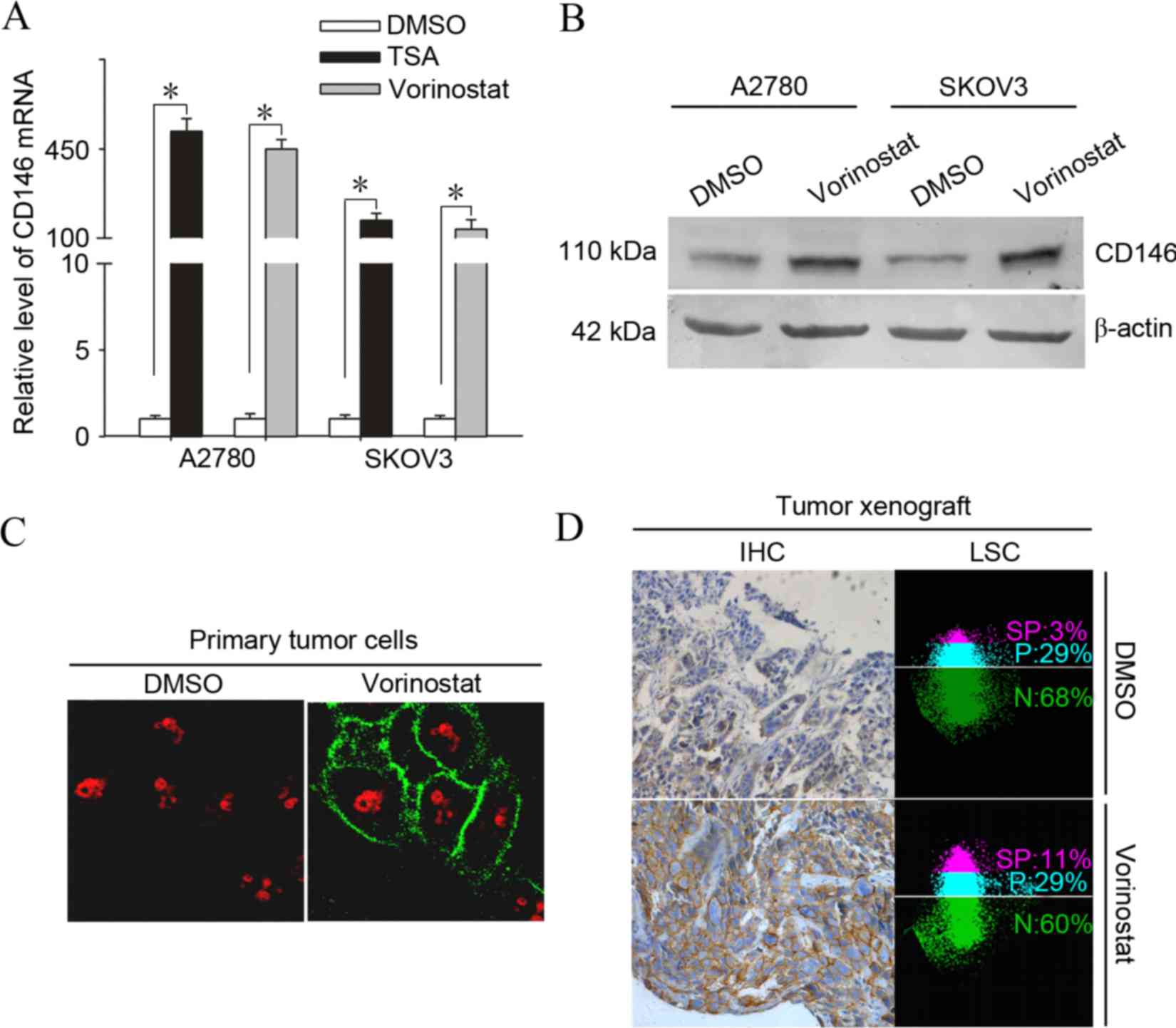

vorinostat for 12 h. As shown in Fig.

1A, subsequent to treatment with vorinostat, transcriptional

induction of CD146 reached an extremely high level, 468.5 fold for

A2780 and 450.3 fold for SKOV3 (P<0.001), compared with the

basal transcriptional level.

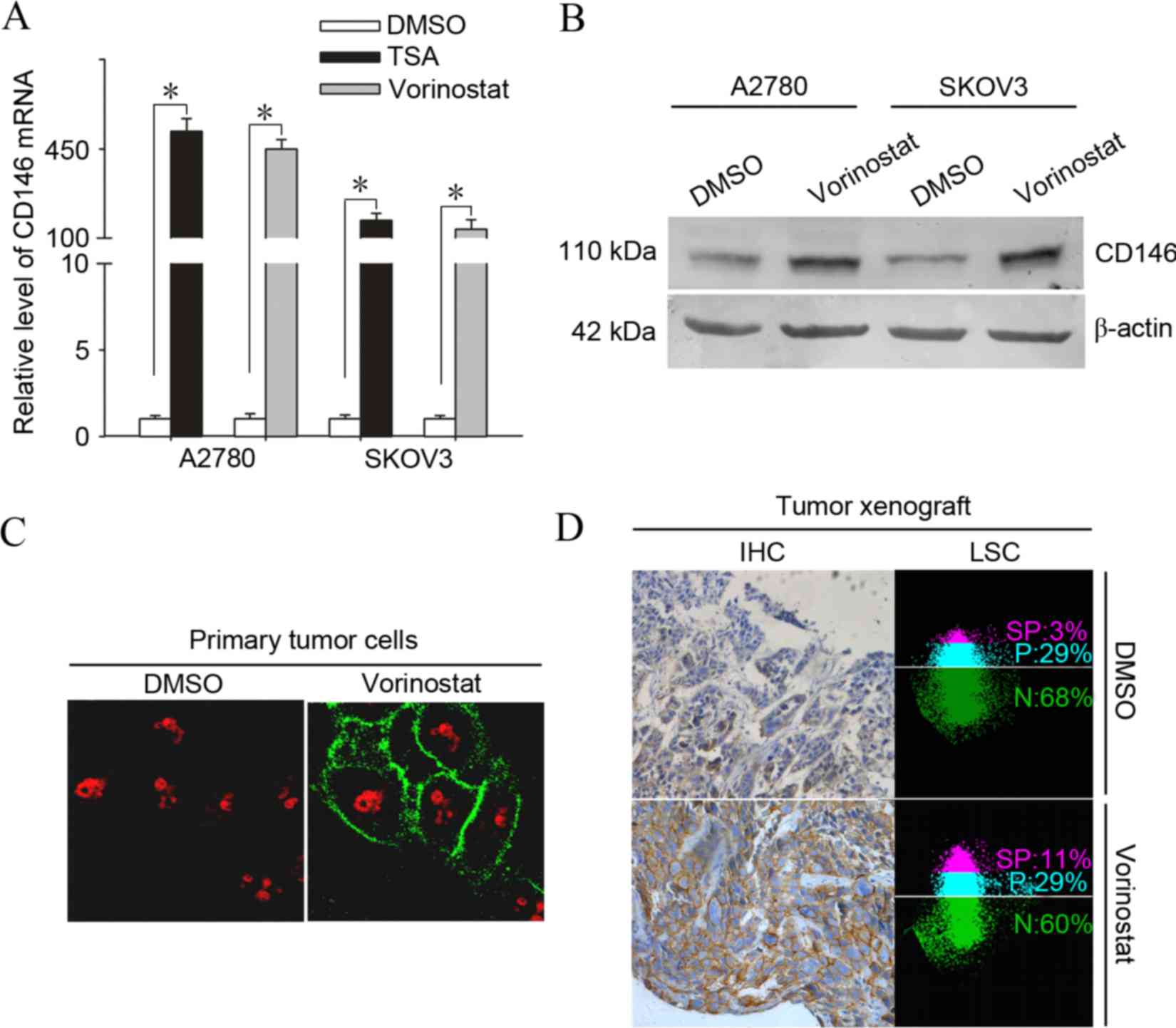

| Figure 1.Induction of the adhesion molecule

CD146 is a common phenomenon in vorinostat-treated ovarian cancer

cells in vitro and in vivo. (A) A2780 and SKOV3 cells

were treated with 2.5 µmol/l vorinostat or 500 nmol/l TSA for 12 h

and subjected to analysis of quantitative polymerase chain reaction

for the mRNA levels of CD146. Results are normalized to those of

18s RNA and expressed as the fold induction compared with the

DMSO-treated group (*P<0.05). (B) A2780 and SKOV3 cells were

treated with 2.5 µmol/l vorinostat for 24 h and analyzed for the

protein levels of CD146 by western blot analysis. (C) A2780 cells

were treated with 2.5 µmol/l vorinostat or DMSO for 12 h and were

then analyzed by immunofluorescent analysis for staining of CD146,

obtaining representative images under a confocal microscope

(magnification, ×600). (D) SKOV3 tumor-bearing mice were treated

with 25 mg/kg of vorinostat or DMSO for 24 h and CD146 expression

was determined by immunohistochemistry and quantified by laser

scanning cytometry. Images represent typical data (Total positive

rate for CD146 (SP plus P) is the mean ± standard deviation (n=10).

CD146, cluster of differentiation 146; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide;

TSA, trichostatin A; SP, strong positive; P, positive; N, negative;

IHC, immunohistochemistry; mRNA, messenger RNA; LSC, laser scanning

cytometry. |

Furthermore, another HDACi, TSA, significantly

induced the expression of CD146, indicating that the induction of

CD146 expression may be a common action shared by HDACi. To

determine whether the vorinostat-induced expression of CD146 occurs

in primary ovarian cancer cells, 8 primary tumor samples from

patients with ovarian cancer were treated with vorinostat.

Vorinostat significantly induced the expression of CD146 as early

as 3 h subsequent to treatment and the increase lasted up to 12 h

in all of the samples examined (Table

I). To test whether the induction of CD146 transcription

upregulated the level of CD146 protein, cultured A2780 cells were

treated with vorinostat or DMSO and examined for CD146 protein

expression using immunofluorescence and western blotting. As

expected, treatment with vorinostat significantly enhanced the

positive immunoreactivity and protein level of CD146 in A2780 cells

(Fig. 1B and C).

| Table I.Effect of vorinostat on the expression

of CD146 in clinical tumor samples. |

Table I.

Effect of vorinostat on the expression

of CD146 in clinical tumor samples.

|

|

|

| Time course, h |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Patients | Clinical

diagnosis | Classification | 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

|---|

| Patient 1 | Ovarian cancer | Serous | 1 | 76.40±7.25 | 16.33±2.78 | 15.97±1.64 |

| Patient 2 | Ovarian cancer | Mucinous | 1 | 77.13±6.65 | 14.02±2.45 | 13.23±1.76 |

| Patient 3 | Ovarian cancer | Serous | 1 | 80.52±7.81 | 18.59±2.97 | 17.13±2.35 |

| Patient 4 | Ovarian cancer | Serous | 1 | 54.21±4.36 | 15.47±3.75 | 11.24±1.88 |

| Patient 5 | Ovarian cancer | Mucinous | 1 | 73.26±6.82 | 21.67±1.98 | 20.57±1.18 |

| Patient 6 | Ovarian cancer | Serous | 1 | 103.42±8.93 | 46.15±2.60 | 37.22±2.71 |

| Patient 7 | Ovarian cancer | Serous | 1 | 66.57±5.33 | 50.14±3.08 | 26.89±3.43 |

| Patient 8 | Ovarian cancer | Serous | 1 | 90.36±7.47 | 65.11±4.23 | 30.78±3.59 |

To address whether the induction of CD146 occurs

in vivo, SKOV3 tumor-bearing mice (n=10) were treated with

vorinostat at 20 mg/kg based on earlier studies (23). Similarly, CD146 expression was

markedly elevated in the tumor cell membrane 24 h subsequent to

treatment with vorinostat, as determined by immunohistochemistry

and quantified by LSC (Fig. 1D); the

total positive rate for CD146 in SKOV3 tumors treated with

vorinostat compared with those treated with DMSO was 40±2 vs.

30±1%, (P=0.001).

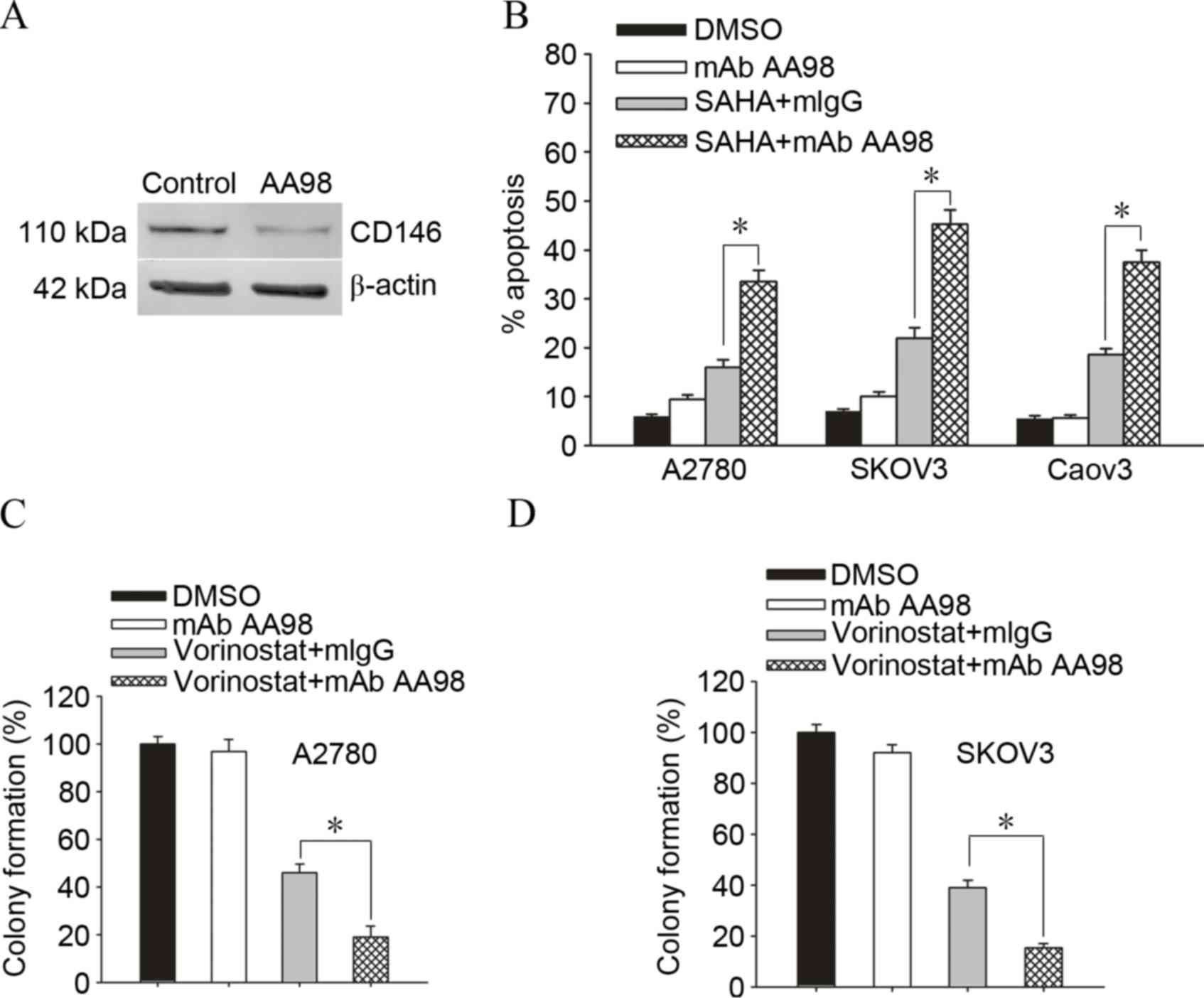

Targeting CD146 substantially enhanced

vorinostat-induced killing in ovarian cancer cells

To additionally confirm whether knockdown of CD146

enhanced vorinostat-induced cell death in ovarian cancer cells,

A2780 ovarian cancer cells were cultured with DMSO or AA98, which

has been confirmed to significantly knockdown the expression of

CD146 (Fig. 2A). A2780/SKOV3/Caov3

ovarian cancer cells are exposed to 2.5 µmol/l vorinostat for 72 h

and subjected to apoptosis assay for the determination of their

drug sensitivity. Accordingly, knockdown of CD146 increased the

sensitivity of A2780/SKOV3/Caov3 ovarian cancer cells to

vorinostat-induced apoptosis (Fig.

2B; A2780, 18.7±3.6 vs. 49.06±4.3%, P=0.001; SKOV3, 16.28±2.9

vs. 38.13±3.5%, P=0.001). Furthermore, knockdown of CD146 promoted

vorinostat-induced killing and gave rise to less survival colonies

in A2780 cells and SKOV3 cells (Fig. 2C

and D; A2780, 46.73±5.2 vs. 19.16±6.3%, P=0.004; SKOV3,

37.55±3.6 vs. 16.23±2.4%, P=0.001).

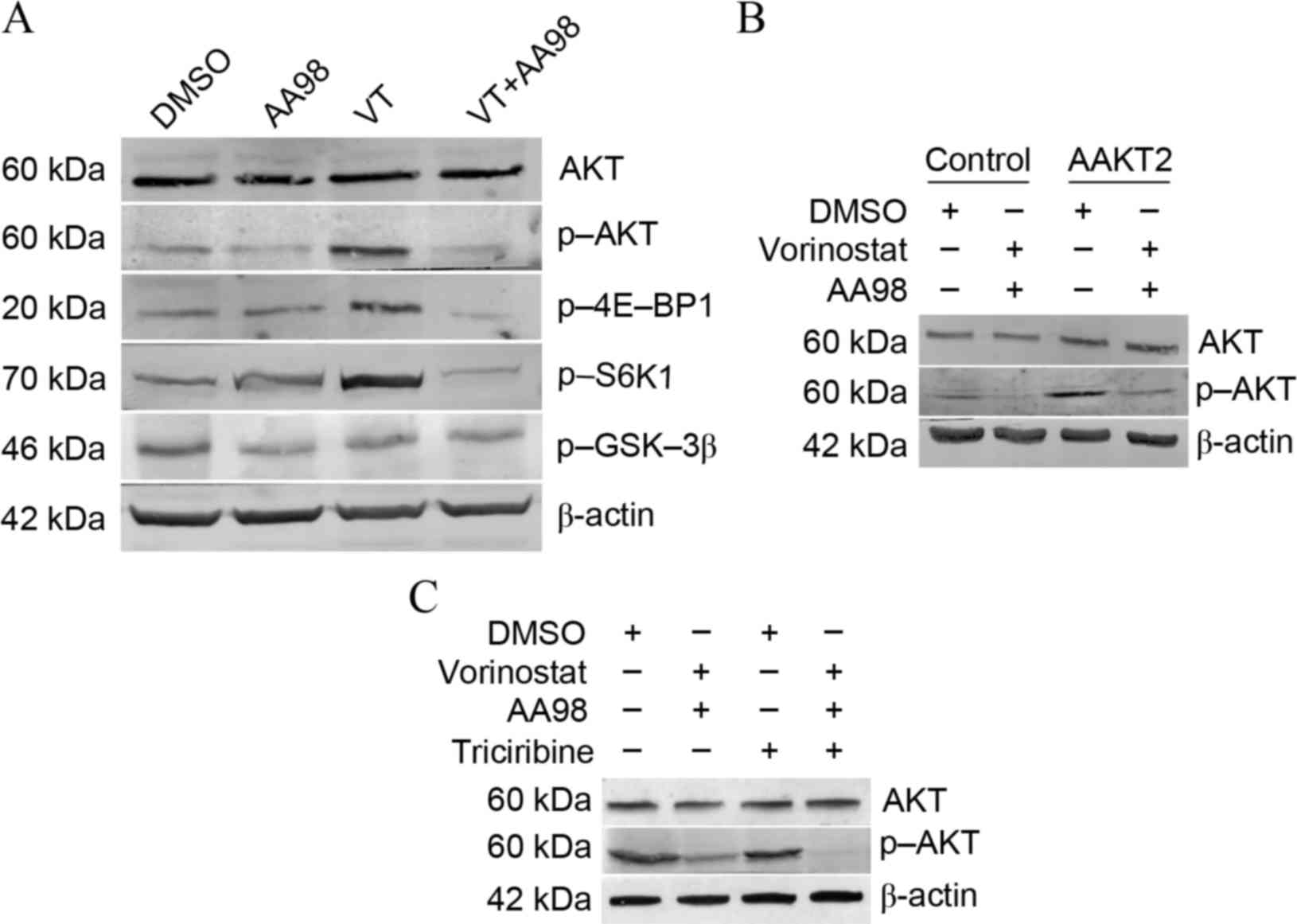

Knockdown of CD146 promotes

vorinostat-induced apoptosis via suppression of the Akt pathway in

ovarian cancer cells

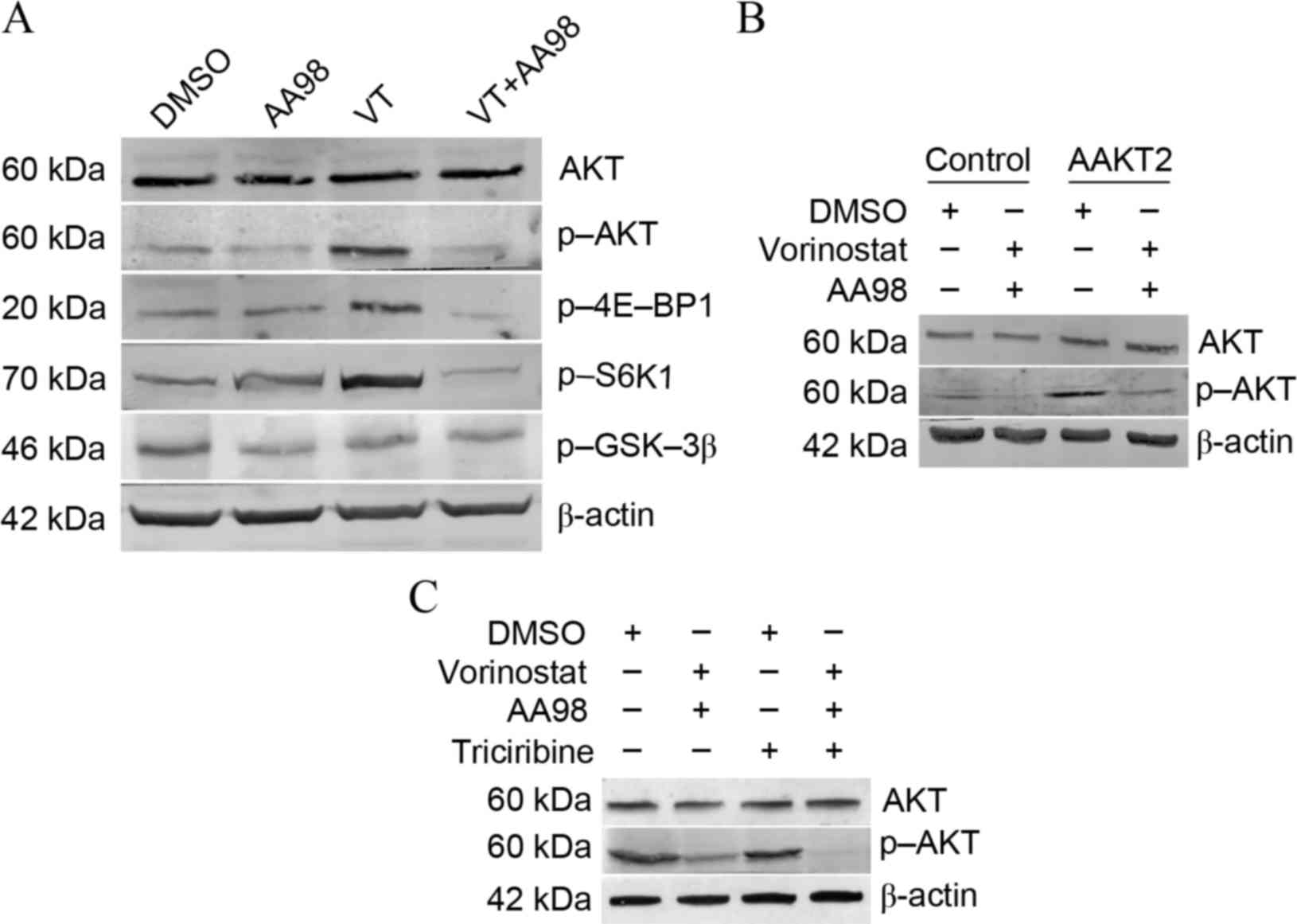

Data has previously shown a link between CD146

expression and Akt activation (24);

therefore, the present study sought to determine the effects of

vorinostat/AA98 on the Akt pathway in ovarian caner cells A2780.

Vorinostat induced the phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream

targets 4E-BP1 and S6K1. AA98 co-administration with vorinostat

reverses the activation of the Akt pathway induced by vorinostat

(Fig. 3A). To additionally confirm

whether Akt had a protective effect on vorinostat/AA98-induced

apoptosis, overexpression/inhibition experiments were performed

using AAkt2 plasmid transfection or triciribine treatment. Although

transfection of AAkt2 inhibited vorinostat/AA98-induced apoptosis,

the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation by triciribine substantially

sensitized A2780 cells to vorinostat/AA98-induced killing (Fig. 3B, control vs. AAKT2, P=0.01; Fig. 3C, control vs. triciribine,

P=0.01).

| Figure 3.Knockdown of CD146 promotes

vorinostat-induced apoptosis via suppression of the Akt pathway in

ovarian cancer cells. (A) A2780 cells were treated as depicted for

24 h (5 µmol/l vorinostat; 10 µg/ml mAb AA98) and examined for

protein levels of total Akt, p-Akt, P-4E-BP1, p-S6K1, p-GSK-3β and

β-actin. VT analysis by western blotting. (B) A2780 cells stably

transfected with the AAkt2 plasmid were treated as depicted for 24

h and examined for protein levels of total Akt and p-Akt by western

blot analysis. A2780 cells stably transfected with pcDNA3.1 plasmid

were treated as control group. (C) A2780 cells were treated with as

depicted for 24 h (5 µmol/l vorinostat; 10 µg/ml mAb AA98; 5 µmol/l

triciribine) and examined for protein levels of total Akt and p-Akt

by western blot analysis. CD146, cluster of differentiation 146;

Akt, protein kinase B; p-, phosphorylated; 4E-BP1, 4E-binding

protein 1; S6K1, ribosomal protein S6 kinase-1; GSK-3β, glycogen

synthase kinase 3β; VT, vorinostat treatment; DMSO, dimethyl

sulfoxide. |

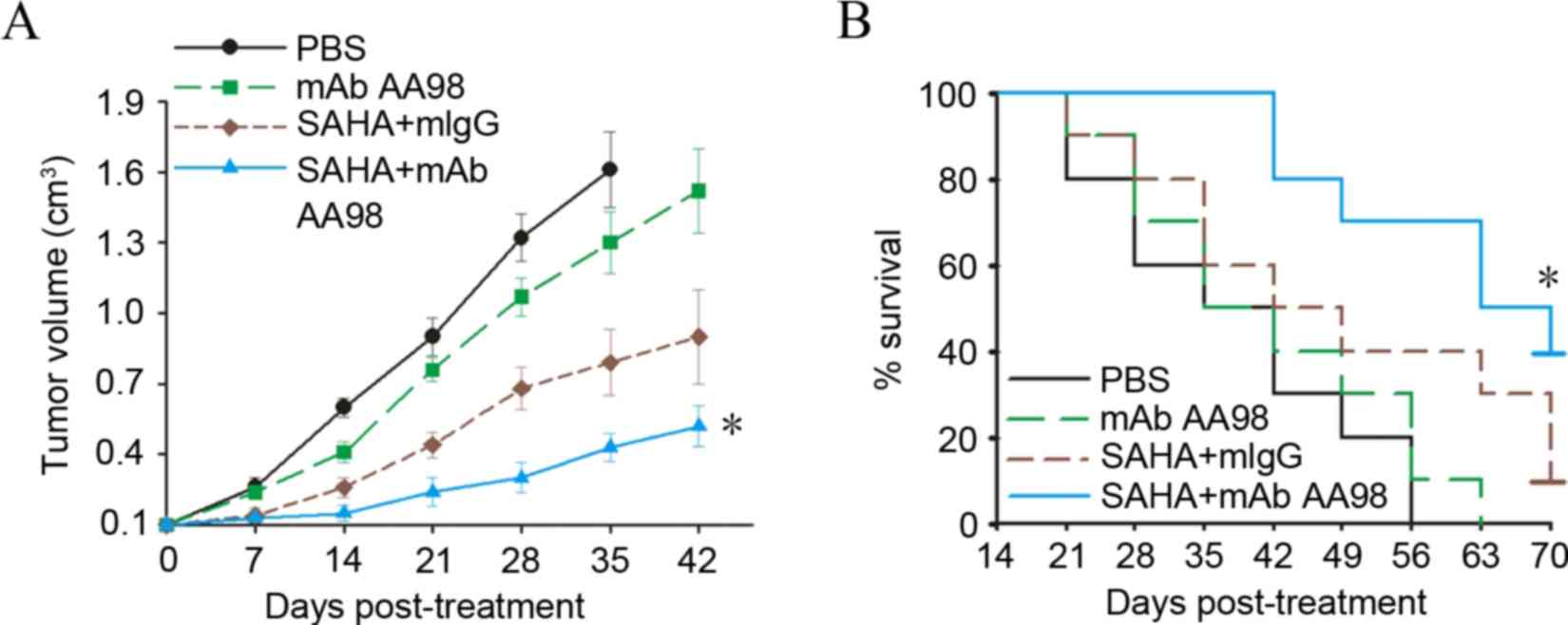

Targeting CD146 synergized with

vorinostat to substantially inhibit ovarian cancer growth

To determine the in vivo antitumor efficacy

of combined vorinostat and AA98, the present study chose lower

doses of the two agents compared with those previously reported

(13). The animal study was completed

when the tumor reached a diameter of 5–6 mm. The SKOV3

tumor-bearing mice were grouped (n=10) and administered

intraperitoneally with AA98 or vorinostat. Although no tumor

complete regression was observed in any groups with different

treatments, tumor growth was significantly retarded in the group

with combined vorinostat and AA98 treatment (P=0.02; Fig. 4A). Furthermore, combined vorinostat

and AA98 treatment significantly improved the survival rate in

SKOV3 tumor-bearing mice (P=0.001; Fig.

4B).

Discussion

The majority of patients with ovarian cancer have

progressed to advanced stages of disease by the first clinical

visit, and are therefore not eligible to be treated with surgery,

and can only receive chemotherapy, with poor results (25). Drug resistance is the primary cause of

mortality in late-stage patients. The flood of new second line

drugs in previous years has provided numerous marked improvements

in anticancer therapy (26). Thus,

the development of new therapeutic strategies and search for novel

genes with new mechanisms of action that can lead to drug

resistance of ovarian cancer cell have become the focuses of

current cancer research.

HDACis have emerged as novel second line drugs, with

their high specificity for tumor cells. However, since the targets

of HDACis are so extensive, it is not surprising that HDACis would

initiate anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic therapeutic responses.

HDACis usually exhibit relatively low potency when used as single

agents. The majority of the current HDACi combination strategies

are more empirical than mechanism-based applications, and

accordingly, are not optimal for this class of drugs (27,28). In

our previous study, a cDNA microarray analysis was conducted and it

was found that the expression of adhesion molecule CD146 was

significantly induced in HDACi-treated tumor cells, particularly in

ovarian cancer cells (13). In the

present findings, it was verified that the induction of CD146 is a

common phenomenon in vorinostat-treated ovarian cancer cells in

vitro and in vivo. Targeting CD146 substantially

sensitized ovarian cancer cells to vorinostat-induced killing.

Treatment with vorinostat plus AA98 also preferentially inhibits

cell proliferation, enhances apoptotic rate of ovarian cancer cells

and ablates cancer colony formation. The present findings provide

the first evidence that an undesired protective signal is initiated

by HDACi and highlight a novel molecular mechanism by which HDACi

induces the expression of CD146 as a protective response to offset

the antitumor efficacy. By contrast, the induction of CD146 may be

exploited as a novel strategy for the enhanced killing of ovarian

cancer cells. Similarly, the synergistic killing effect of

vorinostat and targeting of CD146 was observed in vivo.

Treatment of SKOV3 xenografts with vorinostat plus AA98 resulted in

a more pronounced decrease in tumor volume compared with single

drug-treated mice. Additionally, to inhibit tumor growth, it was

shown that the combined regimen of vorinostat and AA98 is able to

significantly prolong the survival rate of tumor-bearing mice.

It is well known that the sensitivity of cancer

cells to chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis depends on the

balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic signals (29). Therefore, inhibition of anti-apoptotic

signals, such as those mediated by the Akt pathway, has been

proposed as a promising strategy to enhance the efficacy of

chemotherapeutic agents (30). The

present data show that the increased sensitivity to vorinostat

caused by AA98 was strongly associated with Akt signaling in

ovarian carcinomas. The combination of vorinostat with AA98

attenuates Akt phosphorylation and 4E-BP1 expression. A similar

association has been reported between Akt activation and HDACi

sensitivity in cervical cancer cell lines (31). However, Akt kinase activity is not the

sole determinant of sensitivity to vorinostat, and certain factors,

such as S6K1, can result in sensitivity to vorinostat in the

absence of Akt activation (32). In

ovarian cancer A2780 cells, AA98 co-administration reverses the

activation of S6K1 induced by vorinostat. Furthermore, it was

confirmed that Akt had a protective effect on

vorinostat/AA98-induced apoptosis by overexpression/inhibition

experiments.

Collectively, targeting CD146 may be exploited as a

novel strategy to more effectively kill ovarian cancer cells.

However, the identification of an optimal HDACi-based regimen

requires long-term and painstaking clinical trials and suboptimal

application. The current preclinical approach may accelerate the

design of an optimal HDACi-containing regimen in the treatment of

ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from the

Beijing Nova Program (grant no. Z141107001814015), National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81101970) and PhD Programs

Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (grant no.

20111107120009).

References

|

1

|

Suh DH, Lee KH, Kim K, Kang S and Kim JW:

Major clinical research advances in gynecologic cancer in 2014. J

Gynecol Oncol. 26:156–167. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC and

Ledermann JA: Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 384:1376–1388. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zahedi P, Yoganathan R, Piquette-Miller M

and Allen C: Recent advances in drug delivery strategies for

treatment of ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 9:567–583.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Vecchione A, Belletti B, Lovat F, Volinia

S, Chiappetta G, Giglio S, Sonego M, Cirombella R, Onesti EC,

Pellegrini P, et al: A microRNA signature defines chemoresistance

in ovarian cancer through modulation of angiogenesis. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 110:9845–9850. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zwergel C, Valente S, Jacob C and Mai A:

Emerging approaches for histone deacetylase inhibitor drug

discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 10:599–613. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ma XL, Duan H, Liu J, Mo Q, Sun C, Ma D

and Wang J: Effect of LIV1 on the sensitivity of ovarian cancer

cells to trichostatin A. Oncol Rep. 33:893–898. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

West AC and Johnstone RW: New and emerging

HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J Clin Invest. 124:30–39.

2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Slingerland M, Guchelaar HJ and Gelderblom

H: Histone deacetylase inhibitors: An overview of the clinical

studies in solid tumors. Anticancer Drugs. 25:140–149. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Højfeldt JW, Agger K and Helin K: Histone

lysine demethylases as targets for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 12:917–930. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Huang Z, Peng S, Knoff J, Lee SY, Yang B,

Wu TC and Hung CF: Combination of proteasome and HDAC inhibitor

enhances HPV16 E7-specific CD8+ T cell immune response and

antitumor effects in a preclinical cervical cancer model. J Biomed

Sci. 22:72015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Straus DJ, Hamlin PA, Matasar MJ, Lia

Palomba M, Drullinsky PR, Zelenetz AD, Gerecitano JF, Noy A,

Hamilton AM, Elstrom R, et al: Phase I/II trial of vorinostat with

rituximab, cyclophosphamide, etoposide and prednisone as palliative

treatment for elderly patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma not eligible for autologous stem cell

transplantation. Br J Haematol. 168:663–670. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rasheed WK, Johnstone RW and Prince HM:

Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Expert Opin

Investig Drugs. 16:659–678. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ma X, Liu J, Wu J, Yan X, Wu P, Liu Y, Li

S, Tian Y, Cao Y, Chen G, et al: Synergistic killing effect between

vorinostat and target of CD146 in malignant cells. Clin Cancer Res.

16:5165–5176. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang Z and Yan X: CD146, a

multi-functional molecule beyond adhesion. Cancer Lett.

330:150–162. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Xie S, Luca M, Huang S, Gutman M, Reich R,

Johnson JP and Bar-Eli M: Expression of MCAM/MUC18 by human

melanoma cells leads to increased tumor growth and metastasis.

Cancer Res. 57:2295–2303. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu GJ, Wu MW, Wang SW, Liu Z, Qu P, Peng

Q, Yang H, Varma VA, Sun QC, Petros JA, et al: Isolation and

characterization of the major form of human MUC18 cDNA gene and

correlation of MUC18 over-expression in prostate cancer cell lines

and tissues with malignant progression. Gene. 279:17–31. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zabouo G, Imbert AM, Jacquemier J, Finetti

P, Moreau T, Esterni B, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F and Chabannon C:

CD146 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in human

breast tumors and with enhanced motility in breast cancer cell

lines. Breast Cancer Res. 11:R12009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Leslie MC, Zhao YJ, Lachman LB, Hwu P, Wu

GJ and Bar-Eli M: Immunization against MUC18/MCAM, a novel antigen

that drives melanoma invasion and metastasis. Gene Ther.

14:316–323. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xing S, Luo Y, Liu Z, Bu P, Duan H, Liu D,

Wang P, Yang J, Song L, Feng J, et al: Targeting endothelial CD146

attenuates colitis and prevents colitis-associated carcinogenesis.

Am J Pathol. 184:1604–1616. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ma XL, Ma QF, Liu J, Tian Y, Wang B,

Taylor KM, Wu P, Wang D, Xu G, Meng L, et al: Identification of

LIV1, a putative zinc transporter gene responsible for

HDACi-induced apoptosis, using a functional gene screen approach.

Mol Cancer Ther. 8:3108–3116. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Satyamoorthy K, Muyrers J, Meier F, Patel

D and Herlyn M: Mel-CAM-specific genetic suppressor elements

inhibit melanoma growth and invasion through loss of gap junctional

communication. Oncogene. 20:4676–4684. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lei X, Guan CW, Song Y and Wang H: The

multifaceted role of CD146/MCAM in the promotion of melanoma

progression. Cancer Cell Int. 15:32015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cooper AL, Greenberg VL, Lancaster PS, van

Nagell JR Jr, Zimmer SG and Modesitt SC: In vitro and in vivo

histone deacetylase inhibitor therapy with suberoylanilide

hydroxamic acid (SAHA) and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. Gynecol

Oncol. 104:596–601. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zeng Q, Wu Z, Duan H, Jiang X, Tu T, Lu D,

Luo Y, Wang P, Song L, Feng J, et al: Impaired tumor angiogenesis

and VEGF-induced pathway in endothelial CD146 knockout mice.

Protein Cell. 5:445–456. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lheureux S, Karakasis K, Kohn EC and Oza

AM: Ovarian cancer treatment: The end of empiricism? Cancer.

121:3203–3211. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Modugno F and Edwards RP: Ovarian cancer:

Prevention, detection, and treatment of the disease and its

recurrence. molecular mechanisms and personalized medicine meeting

report. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 22:S45–S57. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bots M and Johnstone RW: Rational

combinations using HDAC inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 15:3970–3977.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Khabele D: The therapeutic potential of

class I selective histone deacetylase inhibitors in ovarian cancer.

Front Oncol. 20:1112014.

|

|

29

|

Mohammad RM, Muqbil I, Lowe L, Yedjou C,

Hsu HY, Lin LT, Siegelin MD, Fimognari C, Kumar NB, Dou QP, et al:

Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer. Semin Cancer

Biol. 35:(Suppl). S78–S103. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ocana A, Vera-Badillo F, Al-Mubarak M,

Templeton AJ, Corrales-Sanchez V, Diez-Gonzalez L, Cuenca-Lopez MD,

Seruga B, Pandiella A and Amir E: Activation of the PI3K/mTOR/AKT

pathway and survival in solid tumours: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. PLoS One. 9:e952192014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Feng D, Cao Z, Li C, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Ma

J, Liu R, Zhou H, Zhao W, Wei H and Ling B: Combination of valproic

acid and ATRA restores RARβ2 expression and induces differentiation

in cervical cancerthrough the PI3K/Akt pathway. Curr Mol Med.

12:342–354. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Moschetta M, Reale A, Marasco C, Vacca A

and Carratù MR: Therapeutic targeting of the mTOR-signalling

pathway in cancer: Benefits and limitations. Br J Pharmacol.

171:3801–3813. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|