Introduction

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS) is a rare,

aggressive type of vascular tumor associated with thrombocytopenia

and consumptive coagulopathy. KMS was first reported by Kasabach

and Merritt in 1940, in a boy presenting with enlarging hemangioma

with thrombocytopenia on the left thigh (1). KMS has been associated with Kaposiform

hemangioendothelioma or tufted angioma, but not with the more

common infantile hemangioma (2). Le

Nouail et al (3) estimated the

mortality rate to be between 13% and 24%, depending on the series.

Numerous regimens have been employed for the management of KMS,

without, however, a consistent response, since patients exhibit a

variable and unpredictable response to traditional pharmacological

agents, including steroids, vincristine and interferon (IFN).

Recently, excellent response rates and prompt results have been

achieved by combining antiplatelet therapy with vincristine,

without the use of steroids. Sirolimus, which is directed against

the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase/AKT/mechanistic

target of rapamycin downstream signalling pathway and is involved

in lymphangiogenesis, has also shown promising results (4). No standard guidelines for the treatment

of the disease have been established so far. In certain cases,

multimodal therapy is necessary. The main therapeutic options

include systemic corticosteroid therapy, IFNα2a or 2b, vincristine

and platelet aggregation inhibitors, possibly in combination with

acetylsalicylic acid or ticlopidine (3).

Case report

A 1-year-old pediatric patient was admitted to the

Department of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, The Children's

Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou,

China) for the management of an erythematous and swollen process on

his right shoulder in July 2010. The lesion was a

reddish-violaceous plaque measuring 8×6 cm, irregularly shaped,

poorly demarcated and showed signs of swelling and inflammation

(Fig. 1). The lesion first appeared

as a small skin lesion the size of a peanut. Six months later, it

had increased in size and become slightly tender and warm upon

palpation. Treatment with antibiotics (cefmenoxime, 80 mg/kg) for 1

month failed. Laboratory tests revealed the following: Platelet

count, 77×109/l (normal range, 100–400×109

cells/l); hemoglobin, 115 g/l (normal range,110–140 g/l); leukocyte

count, 9.49×109 cells/l (normal range,

4.00–12.00×109 cells/l); D-dimer, 302 µg/l (normal

range, <500 µg/l). Doppler ultrasound (IU Elite; Philips

Healthcare, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) showed a fluid collection

in the subcutaneous tissue and muscle plane of the patient's right

shoulder and computed tomography scan (Somatom Emotion 16; Siemens

AG, Munich, Germany) demonstrated a vascular tumor extending to the

right clavicle. Based on thrombocytopenia, consumptive coagulopathy

and purpura associated with a huge vascular tumor, the patient was

diagnosed as KMS. Informed consent was obtained from the patient's

parents prior to treatment and the present study was approved by

the Ethical Committee of Zhejiang University.

Treatment with methylprednisolone was administered

intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day for 3 days and tapered off

over 2 weeks. Subsequently, 5 intralesional injections of compound

betamethasone (diprospan) were administered at a dose of 1 ml (7

mg) twice a week, which was equivalent to 10 mg/kg/day

methylprednisolone. Despite the stabilization of the platelet count

following treatment, the lesion continued to enlarge. A weekly

intravenous injection of 1.5 mg/m2 vincristine was

therefore added upon termination of the treatment. Following 6

injections of vincristine at a dose 0.68 mg (according his body

surface area), the platelet count was found to have increased to

264×109/l, and the mass in the right shoulder to have

shrank. The patient was discharged and received weekly blood tests

to ensure that the platelet count was stable.

A month later, the patient was readmitted to the

Department of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, The Children's

Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, presenting with

a cough and a decreased platelet count of 78×109/l. A

posterior-anterior view of the chest was obtained using X-rays,

which demonstrated pneumonia. Several antibiotics were altered for

dealing with pneumonia and the weekly injection of vincristine was

reinitiated for 2 weeks. No further improvement in the platelet

count was observed. Laboratory test results showed the following:

Platelet count, 86×109 cells/l (normal range,

100–400×109 cells/l); white blood cell count,

5.96×109 cells/l (normal range,

4.00–12.00×109 cells/l); hemoglobin, 97 g/l (normal

range, 110–140 g/l); C-reactive protein, <1 mg/l (normal range,

<1 mg/l); D-dimer, 853 µg/l (normal range, <500 µg/l);

prothrombin time, 11.6 sec (normal range, 9.0–14.0 sec); activated

partial thromboplastin time, 23.0 sec (normal range, 23.0–28.0

sec); thrombin time, 18.8 sec (normal range, 15.0–22.0 sec). An

emergency surgery was scheduled. Intraoperatively, completely

resecting the tumor and stopping the bleeding around the right

clavicle was challenging. In the end, partial resection (>90%)

was performed and the wound was repaired by skin grafting. The

patient was intraoperatively supplied with 3 units platelets

(60×109 cells), 1 packed unit red blood cells (20 g

hemoglobin) and 200 ml plasma transfusions. On day 3 following

surgery, the platelet count was 170×109 cells/l, and on

day 10 it was 233×109 cells/l. The surgical specimen was

fixed with 10% neutral formaldehyde (Shanghai Ling Feng Chemical

Reagent Co., Ltd., Changshu, China) for >24 h and paraffin

embedded. The tissue slices (thickness, 4 µm) were stained with

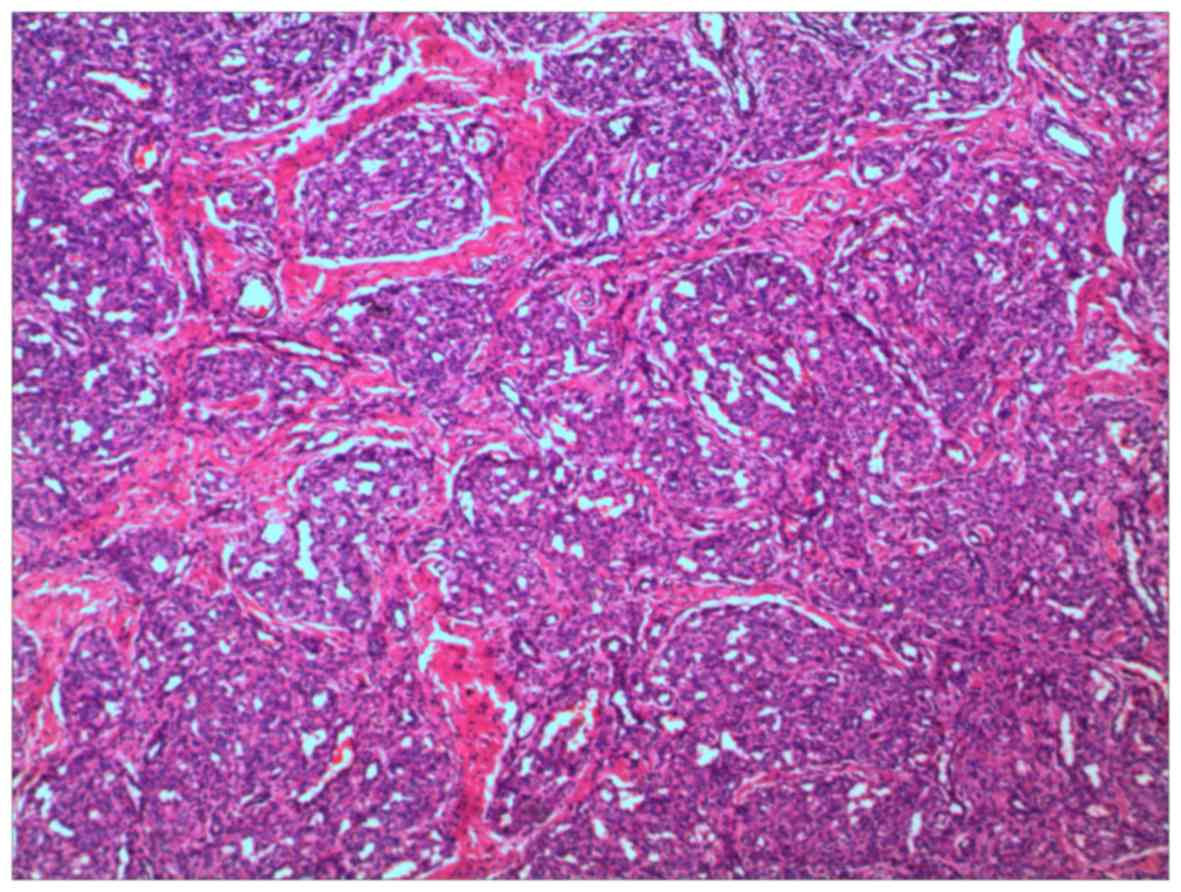

hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathology of the KMS revealed tufted

angioma (TA). A tumor-like distribution of visible clustered

capillary plexus in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue was

observed. Low-magnification microscopy (DMLB2; Leica Microsystems

GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) showed a cannon-like appearance of the

lesion (Fig. 2). No atypia was

identified. Immunohistochemical staining revealed the following:

Cluster of differentiation (CD)31+ (mouse; 1:100

dilution; GA610; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark),

CD34+ (mouse; 1:100 dilution; IR632; DakoCytomation),

smooth muscle actin+ (mouse; 1:100 dilution; IR611;

DakoCytomation), vascular endothelial growth factor+

(mouse; 1:100 dilution; M7273; DakoCytomation),

vimentin+ (mouse; 1:100 dilution; IR630; DakoCytomation)

and glucose transporter 1− (polyclonal rabbit; 1:250

dilution; ab652; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Upon changing the

dressing, the wound was found to be clear and fresh. Two weeks

later, however, wound dehiscence and skin graft necrosis were

reported, while the platelet count was 187×109/l, white

blood cell count 7.33×109/l and C-reactive protein <1

mg/l. Unluckily, a decrease in the platelet count

(79×109/l) was again recorded 3 weeks after the surgery,

so vincristine injections were repeated postoperatively. Following

4 injections over 1 month, the patient was discharged with a

platelet count of 166×109/l and a healing wound.

Half a year later, the patient was readmitted to the

Department of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, The Children's

Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine presenting with

a severely low platelet count of 36×109/l. During

preparation for platelet transfusion, a 63.08% positivity for

platelet antibodies was detected (normal value, <30%). Platelet

transfusion was delayed and propranolol was introduced to the

parents. Due to refractoriness to previous treatments, the parents

agreed to oral administration of propranolol for the treatment of

KMS. First, the dose of propranolol was increased from 6 mg/day to

24 mg/day (split into 3 equal doses) for three days. The dose was

maintained at 24 mg/day in 3 equal doses (2 mg/kg/day) for 3 weeks

until the platelet count increased to 134×109/l. During

that period, a bone marrow puncture was made to confirm the origin

of platelet was normal. Following discharge from the hospital, oral

propranolol at the dose of 30 mg/day in 3 equal doses was

administered for 5 months and subsequently tapered off. Meanwhile,

vincristine was administered intravenously once a month, which

resulted in a continued response for 5 months.

At the time of writing the present study, the

patient was healthy without evidence of relapse for 2 years.

Discussion

KMS is a rare, aggressive type of vascular tumor

that has been associated with thrombocytopenia and consumptive

coagulopathy, which can result in a high risk of bleeding (5). KMS was first noted by Kasabach and

Merritt in 1940 (1). Enjolras et

al (2) suggested that KMS was

caused by either hemangioendothelioma (KHE), TA or a combination of

the two. KHE and TA probably belong to the same neoplastic spectrum

and histological continuum (6).

The histopathology of the present case revealed that

KMS was associated with TA, which is an infrequently observed

benign vascular tumor that was first described by Nakagawa in 1949

under the name angioblastoma (7). The

term TA was introduced by Wilson-Jones and Orkin in 1976, based on

the characteristic histology of the lesion (8). TA is a solitary tumor or infiltrated

plaque believed to have more of an inflammatory appearance than a

vascular abnormality (5). The lesion

has been described as small, cannonball-like, circumscribed

angiomatous tufts and nodules in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue

with characteristic lymphangioma-like vessels (9).

The pathogenesis of KMS remains unknown. Platelet

trapping by an abnormally proliferating endothelium within the

hemangioma may lead to the platelet activation, followed by

secondary activation of coagulation cascades, eventually resulting

in the consumption of various clotting factors (3,10).

Immunohistochemical analysis, using monoclonal antibodies against

platelet marker CD61, and isotope analysis, using

111indium- and 51Cr-labeled platelets, have

supported the importance of platelet trapping for the development

of KMS (10). In addition, excessive

blood flow and sheer stress, secondary to arteriovenous shunts

within the tumors, could lead to further platelet activation

(11).

The management of KMS is challenging due to its

rarity and the lack of well-established systematic treatment

strategies (11). Numerous

therapeutic modalities have been employed for KMS, with no clear

evidence that any type of treatment is superior over others. It has

been suggested that multidisciplinary treatment is required for KMS

(5). Several treatment regimens for

KMS have been reported, including topical or systemic

corticosteroid, IFN, chemotherapy, radiation, laser, propranolol,

sirolimus and surgery (5,11–19; Table

I).

| Table I.Clinical profile of patients with

tufted angioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome arising from tufted

angioma. |

Table I.

Clinical profile of patients with

tufted angioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome arising from tufted

angioma.

| Author, year | Age | Gender | Site | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up | Year of

treatment | Country | Ref. |

|---|

| Ferrandiz-Pulido

et al, 2010 | 1 m | Female | Chin | Predinisone + aspirin

+ VCR + VAC combination + IFN α-2a + Megadose

methylprednisolone | Partial response | 5 y | 2005 | Spain | (5) |

| Kim et al,

2010 | 2 m | Male | Left pubis | Systemic

costicosteroid (DXM + predinisone) | Complete

response | 1 y | 2008 | Korea | (11) |

| Rodriguez et

al, 2009 | 6 w | Female | Left elbow | High-dose

methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/day) + VCR | Near-complete

response | 4 y | 2002 | USA | (16) |

| Wang et al,

2014 | 2 m | Male | Left knee | Predinisolone +

propranolol + VCR + surgery | Complete

response | 3 y | 2010 | China | (17) |

| Chiu et al,

2012 | 2 d | Female | Right thigh | Propranolol (3

mg/kg/day) | Complete

response | 6 m | 2011 | USA | (18) |

| Choi et al,

2013 | 15 d | Male | Left cheek | IFN α-2b +

predinisolone + propranolol + VCR + VAC combination | No response | 6 m | 2011 | Korea | (19) |

In the present study, multimodal treatment with

steroids, vincristine, surgery and propranolol was selected. An

intralesional injection of compound betamethasone (diprospan) was

administered at a dose of 1 ml (7 mg) twice a week, equivalent to

10 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone. As a megadose of a normal

intralesional injection, compound betamethasone (diprospan)

provided fast-acting and slow-acting treatment to ensure the drug

concentration in the lesion was stable.

The reported adverse effects of steroid treatment

include hypertension, cushingoid appearance and opportunistic

infections (10). Vincristine is

considered to be an effective treatment option for TA/KHE; it has

been associated with a low incidence of side-effects and should,

therefore, be used as first-line treatment (12). Vincristine is a vinca alkaloid

antimitotic agent able to block the formation of microtubules in

cells (20). Toxicities associated

with myelosuppression and neurotoxicity require relevant

precautions. In particular, vincristine has been reported to cause

loss of deep tendon reflexes, peripheral neuropathy and abdominal

autonomic disturbance, such as constipation (21). The effects of angiography and

embolization have been shown to be temporary and are used primarily

as an adjunct to surgery, in order to minimize bleeding during a

planned resection (22). In certain

refractory cases, in which the patient cannot be tapered off of the

corticosteroids, chemotherapy is used. Therefore, the most common

chemotherapy used in such cases is cyclophosphamide, either alone

or combined with agents such as vincristine and actinomycin-D

(23). Propranolol is a non-selective

β-adrenergic antagonist, widely used in the treatment of infantile

hemangioma; KMP-associated tumors have been shown to have a

variable response to propranolol, and therefore the optimal dose

has not yet been established (13,18).

Sirolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, was

previously tested in a prospective clinical trial for complicated

vascular anomalies (15). However,

due to the refractoriness of the treatment, the study did not

conclude the best way to deal with KMS.

In a previous study, no platelet antibodies or

evidence of an anti-immune process were found to be responsible for

the destruction of platelets, which suggests that their destruction

may have been due to another mechanism (24). In the present case, however, a

positivity of 63.08% for platelet antibodies was detected (normal

value, <30%). Prothrombin time and activated partial

thromboplastin time have been shown to be either normal or slightly

elevated in KMS (16). There were no

signs of bleeding and platelet transfusion may have been

unnecessary in the present study.

The present study reports a case of KMS as a result

of TA, which was managed with multimodal treatment. Although the

present patient obtained an optimal objective long-term response

with disease control, well-designed, large-scale studies are

required in order to clearly determine the benefits and risks of

multidisciplinary treatment for KMS. However, accumulating

sufficient patients for such studies may be challenging.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Grahay Rester

(Zhejiang Ivy International High School, Hangzhou, China) for

reviewing the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Kasabach HH and Merritt KK: Capillary

hemangioma with extensive purpura: report of a case. Am J Dis

Child. 59:1063–1070. 1940. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Enjolras O, Mulliken JB, Wassef M, Frieden

IJ, Rieu PN, Burrows PE, Salhi A, Léauté-Labreze C and Kozakewich

HP: Residual lesions after Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon in 41

patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 42:225–235. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Le Nouail P, Viseux V and Enjolras O:

Groupe de Recherche Clinique en Dermatologie Pédiatrique:

Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 134:580–586.

2007.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

O'Rafferty C, O'Regan GM, Irvine AD and

Smith OP: Recent advances in the pathobiology and management of

Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 171:38–51. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Mollet J, Sabado C,

Ferrer B and Garcia-Patos V: Tufted angioma associated with

Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: A therapeutic challenge. Act Derm

Venereol. 90:535–537. 2010.

|

|

6

|

Chu CY, Hsiao CH and Chiu HC:

Transformation between Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted

angioma. Dermatology. 206:334–337. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nakagawa K: Case report of angioblastoma

of the skin. Jpn J Dermatol. 59:92–94. 1949.

|

|

8

|

Jones EW and Orkin M: Tufted angioma

(angioblastoma). A benign progressive angioma, not to be confused

with Kaposi's sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 20:214–225. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sadeghpour M, Antaya RJ, Lazova R and Ko

CJ: Dilated lymphatic vessels in tufted angioma: A potential source

of diagnostic confusion. Am J Dermatopathol. 34:400–403. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hall GW: Kasabach-Merritt syndrome:

Pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol. 112:851–862. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim T, Roh MR, Cho S and Chung KY:

Kasabach-merritt syndrome arising from tufted angioma successfully

treated with systemic corticosteroid. Ann Dermatol. 22:426–430.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fahrtash F, McCahon E and Arbuckle S:

Successful treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted

angioma with vincristine. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 32:506–510.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hermans DJ, van Beynum IM, van der Vijver

RJ, Kool LJ, de Blaauw I and van der Vleuten CJ: Kaposiform

hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: A new

indication for propranolol treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

33:e171–e173. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mahendran R, White SI, Clark AH and

Sheehan-Dare RA: Response of childhood tufted angioma to the

pulsed-dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 47:620–622. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, Nelson S,

Lucky A, Elluru R, Dasgupta R, Azizkhan RG and Adams DM: Sirolimus

for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 57:1018–1024. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rodriguez V, Lee A, Witman PM and Anderson

PA: Kasabach-merritt phenomenon: Case series and retrospective

review of the mayo clinic experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

31:522–526. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Z, Li K, Dong K, Xiao X and Zheng S:

Variable response to propranolol treatment of kaposiform

hemangioendothelioma, tufted angioma and Kasabach-Merritt

phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 61:1518–1519. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chiu YE, Drolet BA, Blei F, Carcao M,

Fangusaro J, Kelly ME, Krol A, Lofgren S, Mancini AJ, Metry DW, et

al: Variable response to propranolol treatment of kaposiform

hemangioendothelioma, tufted angioma and Kasabach-Merritt

phenomenon. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 59:934–938. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Choi JW, Na JI, Hong JS, Kwon SH, Byun SY,

Cho KH, Youn SW, Choi HS, Park KD and Park KC: Intractable tufted

angioma associated with kasabach-merritt syndrome. Ann Dermatol.

25:129–130. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Brunton L, Lazo J and Paker K: Goodman

& Gliman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th.

McGraw-Hill; New York: 2005

|

|

21

|

Haisley-Royster C, Enjolras O, Frieden IJ,

Garzon M, Lee M, Oranje A, de Laat PC, Madern GC, Gonzalez F,

Frangoul H, et al: Kasabach-merritt phenomenon: A retrospective

study of treatment with vincristine. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

24:459–462. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Drolet BA, Trenor CC III, Brandão LR, Chiu

YE, Chun RH, Dasgupta R, Garzon MC, Hammill AM, Johnson CM, Tlougan

B, et al: Consensus-derived practice standards plan for complicated

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. J Pediatr. 163:285–291. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hauer J, Graubner U, Konstantopoulous N,

Schmidt S, Pfluger T and Schmid I: Effective treatment of

kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas associated with Kasabach-Merritt

phenomenon using four-drug regimen. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

49:852–854. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

de la Hunt MN: Kasabach-Merritt syndrome:

Dangers of interferon and successful treatment with pentoxifylline.

J Pediatr Surg. 41:e29–e31. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|