Introduction

In patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(DLBCL), rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens can achieve

superior long-term progression-free survival (PFS) and overall

survival (OS) rates relative to regimens that do not contain

rituximab. However, even in the rituximab era, the survival rates

of patients classified as high-intermediate risk or high risk

according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI) (1) remain unsatisfactory (2,3).

Consequently, several randomized control trials (RCTs) (4–8) have

prospectively evaluated the role of upfront autologous stem cell

transplantation (ASCT) following therapy with rituximab plus

cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP)

for high-risk DLBCL. Upfront ASCT was performed as a consolidation

treatment, and part of first-line treatment with induction

chemotherapy. However, although certain studies have reported good

outcomes following treatment with upfront high-dose chemotherapy

(HDT)/ASCT, its usefulness has not been confirmed in RCTs (4–7). Thus, its

significance in the upfront setting remains to be elucidated, and

the majority of guidelines recommend HDT/ASCT as salvage therapy.

However, in actual clinical practice, there is a dilemma regarding

the timing of ASCT in high-risk DLBCL patients who have achieved a

complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) following induction

therapy: It is unclear whether these patients should undergo

upfront HDT/ASCT, or wait until they relapse and subsequently

undergo salvage HDT/ASCT.

The aims of the present retrospective study were to

evaluate the treatment and outcomes of high-risk DLBCL patients who

had received HDT/ASCT, and to identify the clinical factors that

define the patients who achieve improved outcomes following upfront

HDT/ASCT.

Materials and methods

Patients

DLBCL patients diagnosed between January 2006 and

December 2013 at Kansai Medical University Hospital (Hirakata,

Japan) were selected from the hospital database. Overall, the

clinical data of 278 patients were collected. Among them, 66

patients were excluded as they were aged ≥75 years, and were

ineligible for HDT/ASCT. From the beginning, primary central

nervous system lymphoma was not included as its regimen differed

from the standard R-CHOP regimen. Overall, 212 patients aged <75

years were analyzed. Risk category was identified according to the

IPI at initial diagnosis. The age-adjusted (aa) IPI was used for

patients aged <60 years. High-risk patients included those with

high-intermediate-risk or high-risk tumors, while low-risk patients

include those with low-risk and low-intermediate-risk tumors

according to the aaIPI/IPI. Patients who underwent HDT/ASCT were

those who were aged <75 years in the high-risk group, with good

performance status and no severe organ dysfunction. Eligible

patients were almost all recommended to undergo HDT/ASCT at the

beginning of therapy; however, certain patients refused treatment

due to family or economic issues and other factors. Ineligible

patients were those with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

performance status of 3 or 4, concomitant disease, previous

malignancy or major organ dysfunction. Upfront HDT/ASCT was

performed for patients who achieved a first CR or PR following

R-CHOP. High-risk patients who did not undergo HDT/ASCT received

4–8 cycles of R-CHOP. Low-risk patients received R-CHOP or R-CHOP

in combination with radiotherapy, in accordance with the

recommended guidelines. Patients with stable disease or progressive

disease following R-CHOP, or who exhibited relapse, underwent

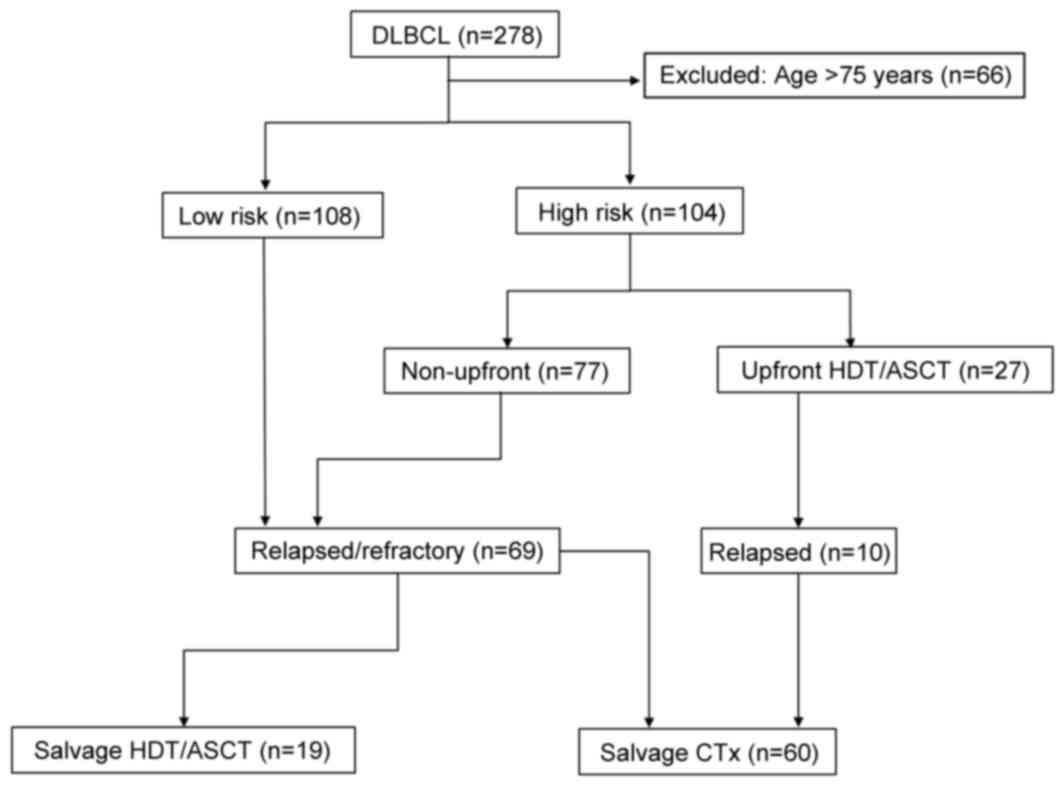

salvage therapy, including salvage HDT/ASCT (Fig. 1).

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Kansai Medical University (Hirakata, Japan).

According to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research

Involving Human Subjects by the Ministry of Health, Labor and

Welfare (9), the present study was a

retrospective study and did not require informed consent from

individual patients. However, the data of the present study was

made available through the website (10) and opportunities were established for

the patients to refuse.

Staging and response criteria

Clinical staging was performed using positron

emission tomography or computed tomography scanning of the neck,

thorax, abdomen and pelvis; bone marrow biopsy; cerebrospinal fluid

examination; and other tools, such as magnetic resonance imaging,

if indicated. The criteria for evaluating the efficacy of treatment

have been described by Cheson et al (11).

Induction therapy

The induction therapy regimen consisted of R-CHOP

(375 mg rituximab/m2 intravenously (i.v), plus 750 mg

cyclophosphamide/m2 i.v, 50 mg doxorubicin/m2

i.v and 2 mg vincristine/m2 i.v on day 1, and 100 mg

prednisone/m2 orally on days 1 through 5) or R-CHOP-like

regimens (for patients with poor cardiac function, doxorubicin may

be removed or replaced with pinorubicin). In the upfront setting,

the treatment response was evaluated after 4–5 cycles of R-CHOP,

and peripheral blood stem cell collection was performed using an

additional cycle of R-CHOP plus etoposide as a harvest regimen (an

established regimen for mobilizing hematopoietic stem cells into

the peripheral blood). In the non-upfront setting, patients

underwent 4–8 cycles of R-CHOP. Patients with refractory or

relapsed disease were treated with salvage regimens consisting of

rituximab, etoposide, ifosfamide and dexamethasone (R-DeVIC), or

rituximab, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine and cisplatin

(R-ESHAP).

HDT

The day of transplantation was set at day 0, and the

conditioning regimen was initiated counting back prior to

transplantation day. Patients undergoing HDT/ASCT received the

following conditioning regimen: Ranimustine (also known as MCNU),

300 mg/m2 on day −6 (6 days before ASCT); etoposide, 200

mg/m2 on days −5 to −2; cytarabine, 200 mg/m2

on days −5 to −2; and melphalan, 140 mg/m2 on day −1.

This regimen (MEAM) is a modified BEAM regimen in which carmustine

(BCNU) is replaced with MCNU due to a lack of accessibility of the

former in Japan. MEAM is one of the most frequently used

conditioning regimens for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies in

Japan (12,13).

Supportive care

Bacterial, fungal, herpes simplex virus and

pneumocystis pneumonitis prophylaxes were administered to all of

the patients in accordance with the guidelines (14,15). In

patients undergoing HDT/ASCT, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

was administered intravenously from day +1 until neutrophil

recovery.

Statistical analysis

OS was measured from the time of ASCT or the final

chemotherapy until the time of mortality from any cause or the

final date of observation. PFS was measured from the time of ASCT

or the final chemotherapy until the time of disease relapse or

progression, mortality from any cause, or the final date of

observation. Survival estimates were calculated using the

Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for univariate

comparisons. To identify the clinical factors that defined the

high-risk DLBCL patients who had an improved outcome from upfront

HDT/ASCT, univariate analysis and the log-rank test were used. All

P-values were two-sided, with P<0.05 considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR

(Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan),

a graphical user interface for R (version 2.13.0; The R Foundation

for Statistical Computing, Australia); EZR is a modified version of

R commander (version 1.6–3) designed to include the statistical

functions frequently used in biostatistics (16).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 212 patients were divided into low-risk

(n=108) or high-risk groups (n=104) according to the aaIPI/IPI.

Among the high-risk patients, 27 underwent upfront HDT/ASCT and 77

received conventional chemotherapy. Of the 212 patients, 79

experienced relapse; there were 33 low-risk patients, 10 patients

treated in an upfront setting involving HDT/ASCT and 36 patients

treated in a non-upfront setting. Among the 79 relapsed patients,

60 patients (including 10 who had relapsed subsequent to upfront

HDT/ASCT) received salvage chemotherapy, and 19 received HDT/ASCT

as salvage therapy. These patients treated with HDT/ASCT received

3–4 cycles of the salvage regimens following relapse; 16 of these

patients achieved a second CR, 1 patient achieved a PR, and 2

patients suffered disease progression (Fig. 1).

Table I shows the

baseline characteristics of the high-risk patients: 27 of these

patients received upfront HDT/ASCT and 77 received conventional

R-CHOP without HDT/ASCT. The median age of the high-risk patients

was 62 years in the upfront setting and 67 years in the non-upfront

setting. In the upfront setting, all patients were categorized as

high-intermediate or high risk according to the IPI, and as

clinical stage III or IV. Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

levels were observed more frequently in the upfront setting,

whereas the incidence of extranodal disease was similar to that in

the non-upfront setting.

| Table I.Characteristics of the high-risk

patients (n=104) who received upfront HDT/ASCT and those who did

not (non-upfront). |

Table I.

Characteristics of the high-risk

patients (n=104) who received upfront HDT/ASCT and those who did

not (non-upfront).

| Characteristic | Upfront | Non-upfront |

|---|

| Total patients

(n) | 27 | 77 |

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

Median | 62 | 67 |

|

Range | 36–72 | 20–75 |

| Sex (%) |

|

|

| Male | 56 | 65 |

|

Female | 44 | 35 |

| IPI/aaIPI (%) |

|

|

|

High-intermediate | 37 | 44 |

| High | 63 | 56 |

| Stage (%) |

|

|

| I | 0 | 5 |

| II | 0 | 0 |

| III | 26 | 26 |

| IV | 74 | 69 |

| Bulky mass (%) | 7 | 4 |

| Extranodal

involvement |

|

|

| at >1 site

(%) | 56 | 58 |

| Elevated LDH level

(%) | 81 | 68 |

| HDT/ASCT as salvage

(%) | 0 | 9 |

Table II shows the

baseline characteristics of the 79 relapsed patients. A total of 19

patients received salvage HDT/ASCT and 60 received salvage

chemotherapy. Patient median age was 58 years in the salvage

HDT/ASCT setting, which was lower than that in the salvage

chemotherapy group, which is the group of patients whom relapsed

and resisted the initial treatment and received chemotherapy

without HDT/ASCT. Factors reflecting tumor burden, namely bulky

mass, extranodal DLBCL and elevated LDH, were observed more often

in the salvage chemotherapy patient group than in the salvage ASCT

patient group.

| Table II.Characteristics of the relapsed

patients (n=79). |

Table II.

Characteristics of the relapsed

patients (n=79).

| Characteristic | Salvage HDT/ASCT | Salvage

chemotherapy |

|---|

| Total patients

(n) | 19 | 60 |

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

Median | 58 | 67 |

|

Range | 36–65 | 37–75 |

| Sex (%) |

|

|

| Male | 74 | 55 |

|

Female | 26 | 45 |

| IPI/aaIPI (%) |

|

|

| Low | 32 | 22 |

|

Low-intermediate | 37 | 17 |

|

High-intermediate | 0 | 33 |

| High | 31 | 28 |

| Stage (%) |

|

|

| I | 11 | 13 |

| II | 32 | 7 |

| III | 37 | 20 |

| IV | 20 | 60 |

| Bulky mass (%) | 0 | 3 |

| Extranodal

involvement |

|

|

| at >1 site

(%) | 21 | 63 |

| Elevated LDH level

(%) | 21 | 63 |

Treatment efficacy and prognosis

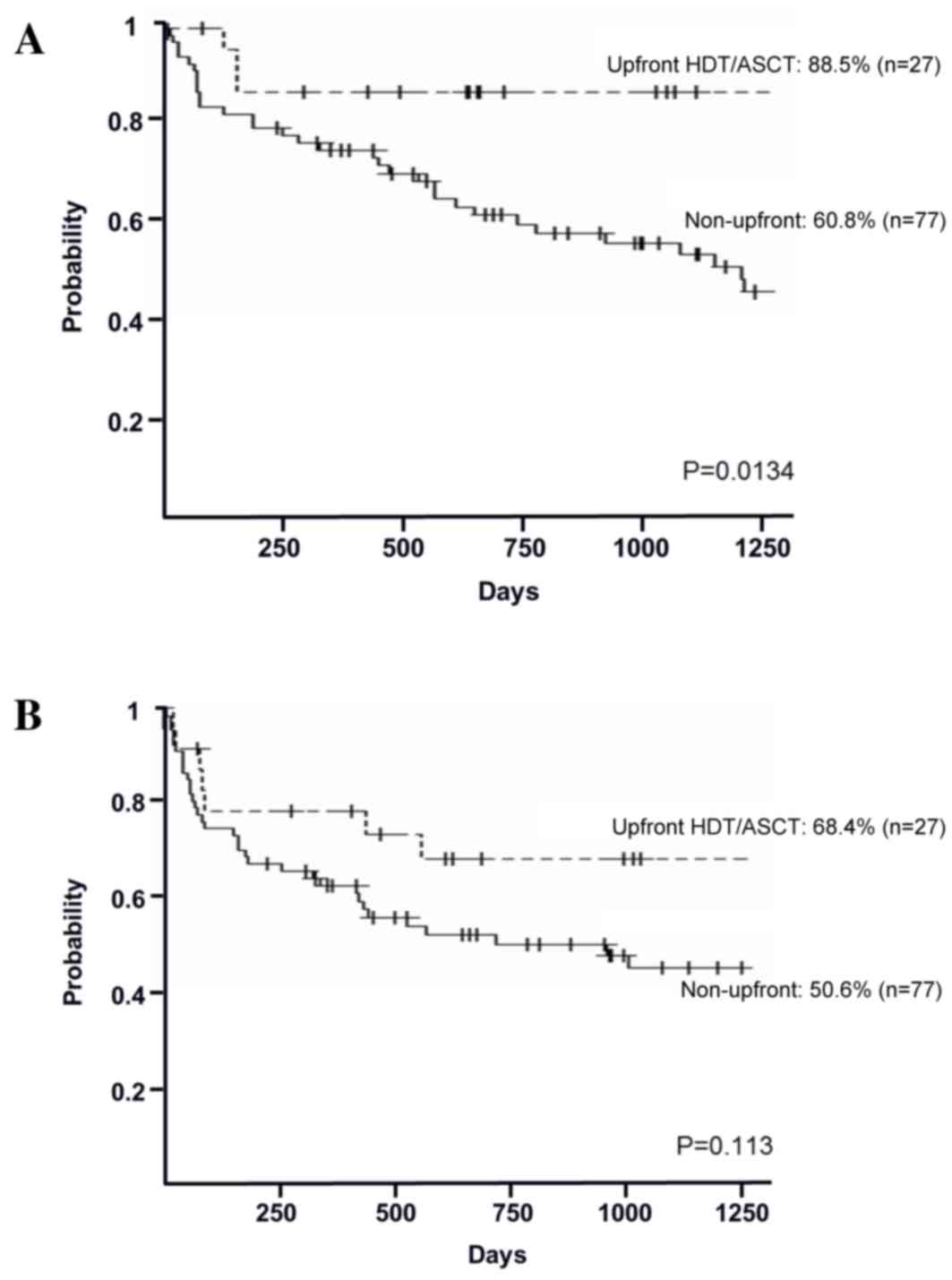

In the high-risk group, the 3-year OS rates in the

upfront and non-upfront settings were 88.5% [95% confidence

interval (CI), 68.4–96.1%] and 60.8% (95% CI, 48.3–71.2%),

respectively (P=0.0134; Fig. 2A). The

3-year PFS rates in the upfront and non-upfront settings were 68.4%

(95% CI, 46.4–82.9%) and 50.6% (95% CI, 38.3–61.6%), respectively

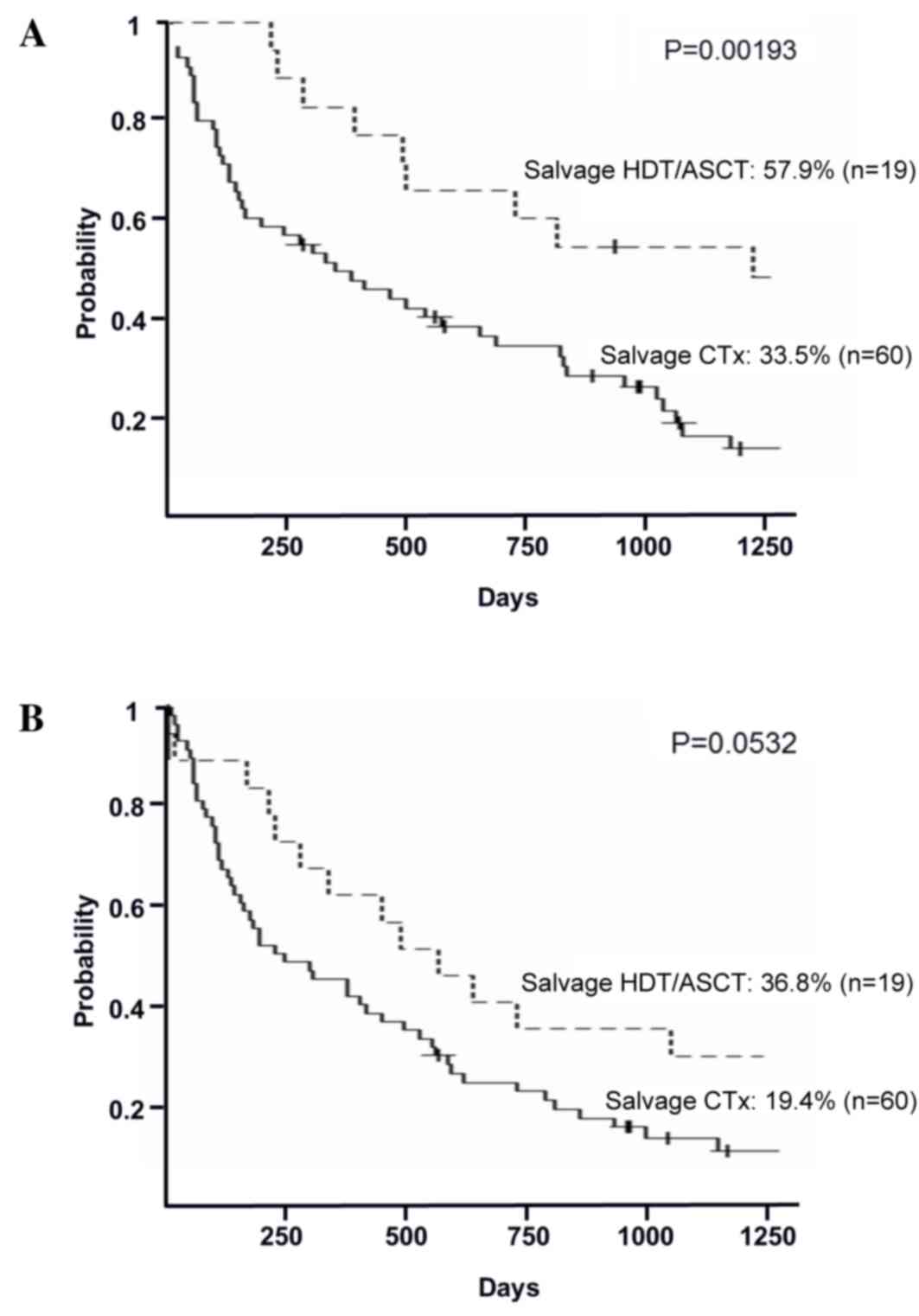

(P=0.113; Fig. 2B). In the relapsed

group, the 3-year OS rates in the salvage HDT/ASCT and the salvage

chemotherapy groups were 57.9% (95% CI, 33.2–76.3%) and 33.5% (95%

CI, 21.7–45.7%), respectively (P=0.00193; Fig. 3A). The 3-year PFS rates in the salvage

HDT/ASCT and the salvage chemotherapy groups were 36.8% (95% CI,

16.5–57.5%) and 19.4% (95% CI, 10.4–30.3%), respectively (P=0.0532;

Fig. 3B).

High-dose regimen-related toxicity and

treatment-related mortality

Common hematological regimen-related toxicities

(RRTs), comprising neutropenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia at

grades 3 and 4, were observed in all patients. The most common

non-hematological RRTs were anorexia and nausea at grades 3 and 4,

which were noted in all patients. Diarrhea and stomatitis were also

commonly observed (80–90% of patients). Mucosal damage was

relatively severe in the salvage HDT/ASCT group. Grade 2 rash was

encountered in both upfront and salvage HDT/ASCT groups. Febrile

neutropenia (FN) was observed in 96% of patients in the upfront

setting and 55% in the salvage setting. In the salvage setting, 1

patient succumbed to FN that occurred prior to engraftment. Another

notable complication was interstitial pneumonia: In the salvage

group, 1 patient died as a result of rapid onset of interstitial

pneumonia. The overall rate of treatment-related mortality (TRM)

was 4.3%.

Univariate analysis

To identify the clinical factors that define

high-risk DLBCL patients who can achieve improved outcomes from

upfront HDT/ASCT, a univariate analysis for 3-year OS rate was

performed. There were no statistically significant prognostic

factors identified in the upfront setting; a hemoglobin level

<11 g/dl was associated with a lower OS rate, without

statistical significance in this setting (P=0.074). A high LDH

level revealed a significant association with survival rate in the

non-upfront setting (P=0.024). Although there were no statistically

differences observed, patients aged >65 years and those with

extranodal disease exhibited poorer OS rates in the non-upfront

setting (Table III).

| Table III.Univariate analysis for 3-year OS rate

in high-risk patients. |

Table III.

Univariate analysis for 3-year OS rate

in high-risk patients.

|

| Upfront | Non-upfront |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | 3-year OS rate

(%) | P-value | 3-year OS rate

(%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) |

| 0.234 |

| 0.393 |

| ≤65 | 83.3 |

| 62.1 |

|

|

>65 | 100.0 |

| 60.2 |

|

| Sex |

| 0.425 |

| 0.735 |

|

Female | 90.9 |

| 65.5 |

|

| Male | 85.7 |

| 58.2 |

|

| Alb (g/dl) |

| 0.386 |

| 0.527 |

|

>3.5 | 88.9 |

| 61.5 |

|

|

≤3.5 | 87.5 |

| 60.6 |

|

| LDH |

| 0.133 |

| 0.024 |

| No | 80.0 |

| 86.2 |

|

|

Yes | 90.5 |

| 50.9 |

|

| Hemoglobin

(g/dl) |

| 0.074 |

| 0.486 |

|

>11 | 94.7 |

| 59.0 |

|

|

≤11 | 71.4 |

| 64.9 |

|

| Extranodal

disease |

| 0.591 |

| 0.668 |

| No | 81.8 |

| 70.6 |

|

|

Yes | 93.3 |

| 57.2 |

|

Discussion

The findings of the present retrospective study

demonstrated the efficacy of upfront HDT/ASCT in patients with

high-risk DLBCL. While certain studies have reported good outcomes

regarding upfront HDT/ASCT (4,6,8), its usefulness has not been confirmed in

RCTs. In terms of the 2-year OS rate, Vitolo et al (4) found no significant differences between

the study arms in which patients were treated with R-CHOP alone or

R-CHOP followed by HDT/ASCT; however, the 2-year PFS rate was

significantly higher in the HDT/ASCT arm (4). Stiff et al (8) reported that in the subset of high-risk

patients alone, induction chemotherapy followed by early HDT/ASCT

significantly improved 2-year PFS and OS rates relative to

chemotherapy alone. Based on this report, as of 2015, the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines include HDT/ASCT as one of

the optional therapies following R-CHOP for high-risk patients who

achieved a CR following induction therapy (17). However, at present, most guidelines

recommend HDT/ASCT as salvage therapy (15,17).

In the present study, a significant difference in

the 3-year OS rate was identified between the upfront ASCT setting

and the non-upfront setting: The 3-year OS rate in the upfront

setting was 88.5% (P=0.0134 vs. non-upfront setting), which was

higher than the 3-year OS rate reported in previous studies

(4–8).

However, there was no statistically significant difference in the

3-year PFS rate between the upfront and non-upfront groups,

indicating that the high-risk patients may eventually relapse, even

after upfront HDT/ASCT. The 3-year OS and PFS rates in the

non-upfront setting were 60.8 and 50.6%, respectively, and were

significantly lower than those in the upfront setting (P=0.113 for

PFS rate). These results confirmed that upfront HDT/ASCT for

high-risk DLBCL is a feasible and promising therapy.

As the majority of guidelines recommend HDT/ASCT as

salvage therapy, a comparison between salvage HDT/ASCT and salvage

chemotherapy was performed in the present study. The 3-year OS rate

of the salvage HDT/ASCT group was 57.9% (P=0.00193), which is

unsatisfactory in comparison with the OS rate of the upfront

HDT/ASCT group. The 3-year PFS rate in this setting was 36.8%

(P=0.0532), which revealed that relapse was frequent even after

salvage HDT/ASCT. These results indicate that DLBCL is frequently

resistant to chemotherapy following relapse. The patients in the

salvage HDT/ASCT group were younger on average than those in the

salvage chemotherapy group; this indicates that patients who are

able to undergo salvage HDT/ASCT must be limited due to age or

co-morbidity. Thus, the timing of HDT/ASCT administration is

critical. If patients are eligible, it would be beneficial for them

to undergo HDT/ASCT as an early treatment before they become

therapy-resistant or more elderly with more complications.

In the present study, the common RRTs were anorexia,

nausea, diarrhea, stomatitis and FN. In total, 2 patients died due

to interstitial pneumonia or FN; as these 2 patients were treated

in the salvage setting, potential organ damage caused by prior

chemotherapies may have caused these lethal adverse effects.

However, according to the present results, the TRM rate was low

(4.3%); thus, we suggest that there is no reason to avoid HDT

following ASCT if patients are eligible.

HDT/ASCT may be tolerable and effective; however,

serious adverse effects can occur. Therefore, it is necessary to

identify patient groups that will gain the maximum benefit from

upfront HDT/ASCT. In this regard, the most accurate prognostic

factors must be determined. Using univariate analysis, the present

study did not reveal any significant prognostic factors in the

upfront setting. Notably, patients in the upfront setting with

advanced age (>65 years), elevated LDH levels or extranodal

disease had a better prognosis than younger patients, those with

normal LDH, or those without extranodal disease, respectively; this

suggests that HDT/ASCT may overcome the unfavorable outcomes caused

by these prognostic factors.

The present study had a number of limitations.

First, a small patient cohort was evaluated and the follow-up

period was short. To determine the true efficacy of HDT/ASCT, a

longer follow-up period will be required. Furthermore, biological

features, such as genetic abnormalities or CD5 expression, were not

considered. These factors are expected to be important in the

prediction of survival. In the present study, the 3-year OS and PFS

rates were superior to those previously reported for the following

reasons. First, as our institute is a university hospital, patients

had already been selected before they attended our out-patient

department; consequently, there would have been a selection bias.

Second, it is suspected that the use of the IPI will fail in the

classification of appropriate patients for upfront HDT/ASCT; it has

been reported that the IPI cannot be used to predict the outcome of

a patient group with poor prognosis where the 5-year OS rate is

<60% (3). Thus, the population

must have included patients with a good prognosis who did not

require upfront treatment with HDT/ASCT. Therefore, it is necessary

to establish prognostic factors additional to the IPI that can be

used to identify the patients who will benefit from upfront

HDT/ASCT. In the current study, no significant prognostic factors

associated with upfront HDT/ASCT could be determined. A

sufficiently large study population will be required to provide the

statistical power to adequately assess these factors, and

prospective studies will be required to confirm the efficacy of

upfront HDT/ASCT.

In conclusion, the use of upfront HDT/ASCT in

patients with high-risk DLBCL is feasible and may improve their

outcome. HDT/ASCT should be administered as an early treatment

before patients become therapy-resistant.

References

|

1

|

A predictive model for aggressive

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 329:987–994. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, Glass

B, Schmitz N, Pfreundschuh M and Loeffler M: Standard international

prognostic index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients

with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin

Oncol. 28:2373–2380. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald

C, Gill K, Hoskins P, Klasa R, Savage KJ, Shenkier T, Sutherland J,

et al: The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a

better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood.

109:1857–1861. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Vitolo U, Chiappella A, Brusamolino E, et

al: A randomized multicenter phase III study for first line

treatment of young patients with high risk (AAIPI 2–3) diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Rituximab (R) plus dose-dense

chemotherapy CHOP14/MEGA CHOP14 with or without intensified

high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) and autologous stem cell

transplantation (ASCT). Results of DLCL04 trial of Italian lymphoma

foundation (FIL). Ann Oncol. 22:1062011.

|

|

5

|

Schmitz N, Nickelsen M, Ziepert M, Haenel

M, Borchmann P, Schmidt C, Viardot A, Bentez N, Peter N, Ehninger

G, et al: Conventional chemoimmunotherapy (R-CHOEP)-14 or high-dose

therapy (R-Mega-CHOEP) for young, high-risk patients with

aggressive B-cell lymphoma: Final results of the randomized

Mega-CHOEP trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Study Group (DSHNHL). J Clin Oncol. 29:80022011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Stiff PJ, Unger JM, Cook J, Constine S,

Couban S, Shea TC, Winter JN, Miller TP, Tubbs RR, Marcellus DC, et

al: Randomized phase III U.S./Canadian intergroup trial (Swog

S9704) comparing CHOP (+/−) R for eight cycles to CHOP (+/−) R for

six cycles followed by autotransplantation for patients with

high-intermediate (H-int) or high IPI grade diffuse aggressive

non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). J Clin Oncol. 29:80012011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Le Gouill S, Milpied NJ, Lamy T, Delwail

V, Gressin R, Guyotat D, Damaj GL, Foussard C, Cartron G,

Maisonneuve H, et al: First-line rituximab (R) high-dose therapy

(R-HDT) versus R-CHOP14 for young adults with diffuse large B-Cell

lymphoma: Preliminary results of the GOELAMS 075 prospective

multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 29:80032011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Stiff PJ, Unger JM, Cook JR, Constine LS,

Couban S, Stewart DA, Shea TC, Porcu P, Winter JN, Kahl BS, et al:

Autologous transplantation as consolidation for aggressive

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 369:1681–1690. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare,

. Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving

Human Subjects. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10600000-Daijinkanboukouseikagakuka/0000080278.pdf

|

|

10

|

http://www.kmu.ac.jp/hirakata/visit/treatment/medical_section/ketuekishuyounaika.html

|

|

11

|

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp

MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, Lister TA, Vose J, Grillo-López A,

Hagenbeek A, et al: Report of an international workshop to

standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI

Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 17:12441999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kameoka Y, Takahashi N, Ishizawa K, Kato

Y, Ito J, Sasaki O, Murai K, Noji H, Hirokawa M, Tajima K, et al:

Safety and feasibility of high-dose ranimustine (MCNU),

carboplatin, etoposide and cyclophosphamide (MCVC) therapy followed

by autologous stem cell transplantation for malignant lymphoma. Int

J Hematol. 96:624–630. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kawabata K, Hagiwara S, Takenouchi A,

Tanimura A, Tanuma J, Tachikawa N, Miwa A and Oka S: Autologous

stem cell transplantation using MEAM regimen for relapsed

AIDS-related lymphoma patients who received highly active

anti-retroviral therapy: A report of three cases. Intern Med.

48:111–114. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in

Oncology: Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Infections.

Version 1. 2017.https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp

|

|

15

|

Japanese Society of Hematology, . clinical

practice guideline. http://www.jshem.or.jp/gui-hemali/table.html

|

|

16

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in

Oncology: Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Version 2. 2016.https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp

|