Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is more common in

Eastern countries, including Japan. Despite the pathological

difference, esophageal cancer has a poor prognosis due to early

metastasis and direct invasion. Multimodal therapies including

surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy are necessary; however, the

response rate to chemoradiation therapy is low; in one Japanese

study it was found to be 68% in patients with advanced SCC in the

thoracic esophagus (1). Although

chemo or radiosensitivity is closely related to prognosis, it is

currently impossible to predict the therapeutic effect of

therapies. Therefore, detecting resistant genes and mechanisms is

essential for tailoring treatment to improve the prognosis.

Many studies have shown numerous genes or microRNA

related to radioresistance in esophageal cancer cells (2). A few comprehensive gene analyses by

microarrays have also detected many candidate radioresistant genes

(3,4).

However, most radioresistant genes are not yet known and the

mechanisms underlying their radioresistance remain unclear.

Comprehensive gene screening with transposons is a

novel procedure for systematically identifying chemoresistant

genes, developed by Chen et al in 2013 (5). A transposon is a mobile genetic element

which transports at random to other locations in the genome. By

inserting a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promotor as a transcriptional

activator in the transposon, the following gene in the new location

will be overexpressed and the gene located at the transposon

insertion site will be downregulated. We inserted transposons into

tumor cells to form a library of ‘transposon-tagged cells.’ Each

transposon-tagged cell has randomly activated or inactivated genes.

After drug treatment is administered to the cell library, the

surviving cells can either have overexpressed chemoresistant genes

or downregulated chemosensitive genes due to the transposons with

the CMV promoter. By detecting the location of the transposon in

surviving cells, it is possible to pick up candidate

chemotherapy-resistant genes. What makes this screening method

distinct is that it is a gain-of-function genetic screening, unlike

past genetic interrogation approaches for genomes. Thus, this

screening can be used to survey untranscribed regions (5).

Using this technique, we have already succeeded in

generating cell libraries and identifying candidate genes for

cisplatin resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

(6). The aim of the present study is

to use this method to identify candidate radioresistant genes in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and treatments

We established transposon-tagged cells in TE4 and

TE15, human well-differentiated esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

cell lines provided by the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical

Research Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku

University (Sendai, Japan) (6).

Puromycin-resistant genes in transposons were also inserted into

the transposon-tagged cells for puromycin selection. The cell lines

were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and

penicillin-streptomycin solution (penicillin 10,000 U/ml,

streptomycin 10,000 µg/ml, puromycin 0.5 µg/ml) (all from Nacalai

Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). In all the experiments, the cells were

cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere consisting of 5%

CO2 in the air. The parent cell lines, TE4, and TE15,

were cultured without puromycin.

Radiation treatment

Around 250,000 transposon-tagged cells were plated

on 100-mm tissue culture dishes for radiation treatment. Dishes

were irradiated by 9–11 Gy using an X-ray cell irradiator, CellRad

(Faxitron Bioptics, Tucson, AZ, USA). Irradiated cells were

cultured for more than 14 days until radioresistant cells (RRCs)

formed colonies.

Comprehensive gene screening with

transposon

The base sequences of the transposons' insertion

sites were detected using Splinkerette polymerase chain reaction

(PCR), TOPO cloning, and Sanger sequencing performed in accordance

with the protocol of our previous study (6). Insertion sites were aligned using the

BLAST function of the National Library of Medicine (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). We included

a maximum of 15 genes that had somewhat similar sequences (blastn)

as candidate genes for each colony.

Real-time quantitative PCR

analysis

The cells were harvested, and total RNA was

extracted with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The

concentration of total RNA was determined using a NanoDrop 2000c

(NanoDrop Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized

from total RNA using a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) in accordance with the

manufacturer's protocol. PCR reaction mixes were prepared using the

template cDNA samples and Fast SYBR-Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), while the expressions of human cytochrome

c oxidase 1 (MT-CO1), cytochrome c oxidase

subunits 2 (MT-CO2), and 3 (MT-CO3), ND2, and

GAPDH were analyzed using a ViiA7 Real-Time PCR system

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc). The thermal cycling reaction

included incubation at 95°C for 20 sec, 40 cycles of 95°C for 3

sec, and 60°C for 30 sec. Data were collected using analytical

software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The expression

level of each gene was determined using the ΔΔCt method.

MTT assay

Survival rates after irradiation were measured by an

MTT assay. One day before 7-Gy irradiation, 5×102/well

of TE4 cells and MT-CO1-downregulated cells were seeded on a

96-well plate. TE4 cells and MT-CO1-downregulated cells with

and without irradiation were incubated with MTT (3-(4,

5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, a yellow

tetrazole) for 3 h and incubated with dimethyl sulfoxide for 20

min. The survival rate after irradiation was measured as the ratio

of absorbance at 550 nm of irradiated cells to non-irradiated

cells.

Cytochrome c oxidase assay

A cell pellet of 10 million cells was resuspended in

200 µl of a cell lysis buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM

HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM Na-EGTA, 1.5 mM Na-EDTA, 1 mM

MgCl2, and a protease inhibitor cocktail. After a 20-min

incubation on ice, the cells were disrupted with a Dounce

homogenizer (50 strokes with a loose glass pestle and 50 strokes

with a tight glass pestle). The resulting homogenates were

immediately used in the cytochrome c oxidase assay.

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was determined

by using a Cytochrome c Oxidase Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich,

St. Louis, MO, USA). Absorbance at 550 nm of ferrocytochrome

c was measured using NanoDrop 2000c (NanoDrop Technologies).

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured as the reduction

in absorbance in the sample at 550 nm.

To get reduced cytochrome c, 2.7 mg of

cytochrome c, dissolved in 1 ml water, was incubated with 5

µl of 0.1 M 1.4-dithiothreitol (DTT) for 15 min on ice. The

reduction in absorbance at 550 nm for 10 min was measured

immediately after adding 50 µl of reduced cytochrome c

solution to 950 µl of the homogenate (100 µg of total protein).

Caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was determined by using an

APOPCYTO™ Caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay kit (Medical &

Biological Laboratories, Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan). After 5-Gy

irradiation, a 3×105/well of TE4 cells and

MT-CO1-downregulated cells were seeded on a 96-well plate.

Caspase-3 activity was measured by NanoDrop 2000c as the absorbance

at 405 nm after incubation with a colorimetric substrate (DEVD-pNA)

with cell lysate (90 µg of total protein in 50 µl of lysing buffer)

at 37°C for 24 h.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were performed using Student's

t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. IBM SPSS Statistics version 21

(IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses. A

p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Detection of candidate radioresistant

genes

After irradiation of the TE4 and TE15

transposon-tagged cells, 108 radioresistant colonies were picked

up. The nucleotide sequences of the transposons' insertion sites in

each colony were amplified by Splinkerette PCR and TOPO cloning.

Fifty nucleotide sequences were thus, detected. Insertion sites

were searched for by aligning the detected nucleotide sequences on

the BLAST site. The genes located up to 25 kbp downstream from the

insertion site were identified as candidate radioresistant genes.

Eleven such genes were detected; these are listed in Table I.

| Table I.List of the 11 candidate

radioresistant genes detected by cyclopedic gene screening with

transposons. |

Table I.

List of the 11 candidate

radioresistant genes detected by cyclopedic gene screening with

transposons.

| Gene |

Overexpression/downregulation | Number of

detection |

|---|

| Sorting nexin 3

(SNX3) | Downregulation | 3 |

| Cytochrome c

oxidase 1 (MT-CO1) | Downregulation | 3 |

| mediator of RNA

polymerase II transcription subunit 13 (MED13) | Downregulation | 2 |

| Yae1 domain

containing protein 1 isoform 2 (YAE1D1) | Overexpression | 1 |

| centromere protein

V | Downregulation | 1 |

| Signal-induced

proliferation associated 1 like protein2 (SIPA1L2) | Downregulation | 1 |

| beta crystallin A4

(CRYBA4) | Overexpression | 1 |

| RNA-binding motif

single-stranded interacting protein 3 (RBMS3) | Downregulation | 1 |

| Transcription

factor 4 isoform 1, isoform 4 | Downregulation | 1 |

| protein FAM178B

isoform A (FAM178B) | Downregulation | 1 |

| Nck-associated

protein 5 (NCKAP5) | Downregulation | 1 |

Nucleotide sequences of the transposon's insertion

site matched a part of the gene sequence of nine genes which may

have been downregulated by the inserted transposons. Two genes were

detected downstream of the transposon's insertion site and may have

been overexpressed by the CMV promoter in the transposon. Three

genes were detected in two or three different radioresistant

colonies.

MT-CO1 was one of the detected candidate

radioresistant genes, found in three radioresistant colonies. One

hundred ninety-one nucleotide bases, detected by sequence, matched

the base sequence of MT-CO1 coded in mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) with a 99% concordance rate. Cytochrome c oxidase is

known to be an enzyme associated with apoptosis by activating the

caspase cascade. Thus, we conducted further experiments on the

hypothesis that downregulation of MT-CO1 induced

radioresistance by blocking activation of the caspase cascade in

esophageal cancer cells.

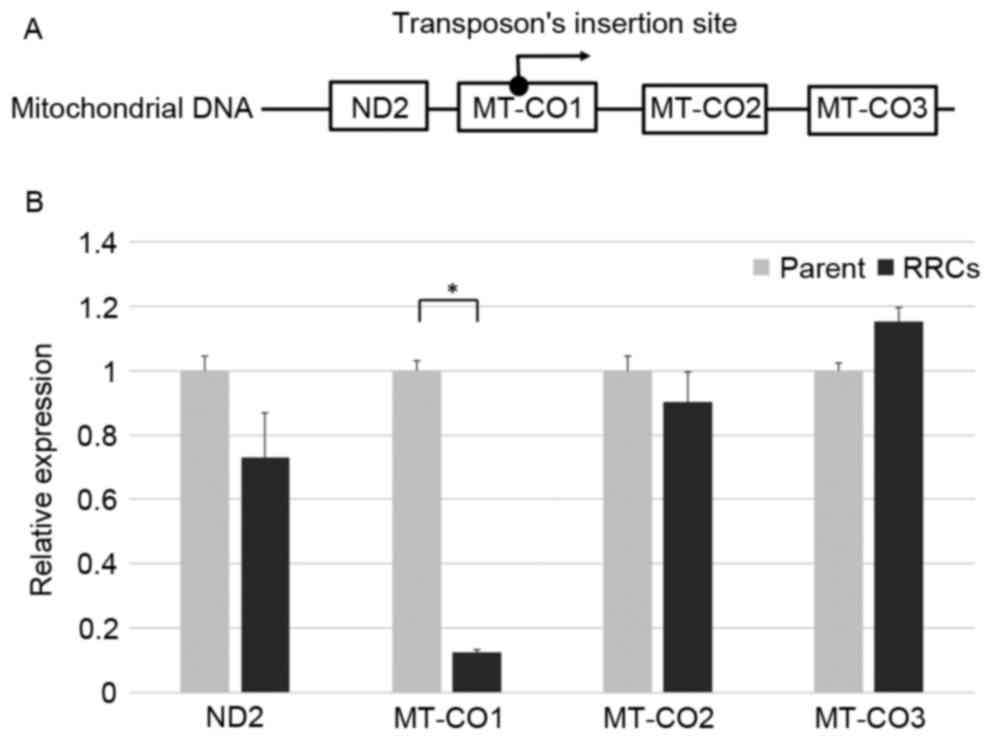

Downregulation of MT-CO1 in RRCs

In RRCs in which transposon was inserted into the

MT-CO1, MT-CO1 may be downregulated by the inserted

transposon; and MT-CO2 and MT-CO3, coded downstream

of MT-CO1, could possibly have been overexpressed by the CMV

promotor in the transposon (Fig. 1A).

The relative expression levels of MT-CO1, MT-CO2, and

MT-CO3 were 0.12, 0.90, and 1.15, respectively, when the

expression level of parent TE4 cell was 1. MT-CO1 was

significantly downregulated in these cells (P<0.001) (Fig. 1B).

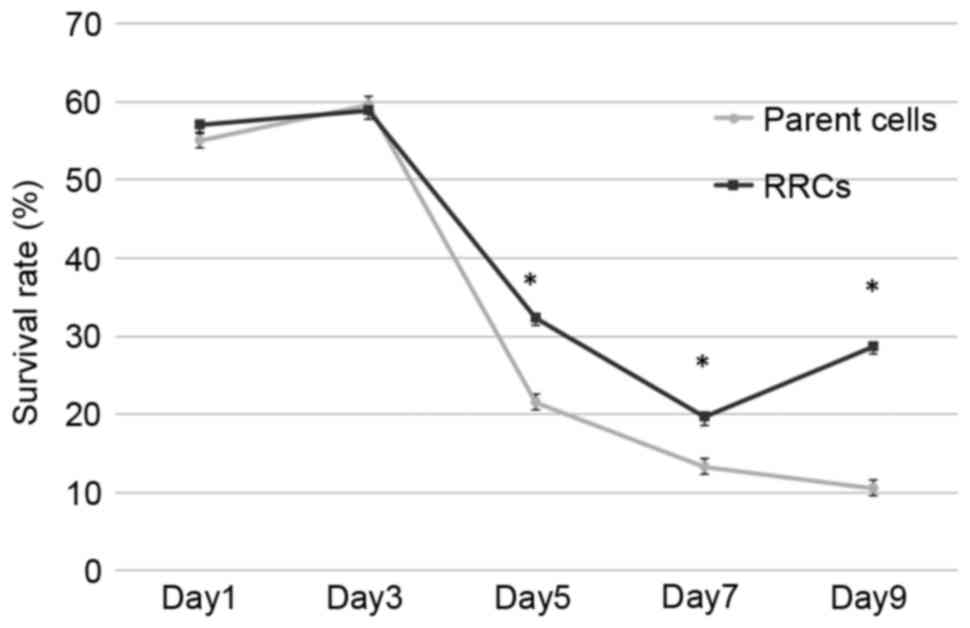

Radioresistance and downregulation of

MT-CO1

To establish whether the RRCs (in which

MT-CO1 was inactivated) showed radioresistance, survival

rates after irradiation were measured by an MTT assay (Fig. 2). The relative survival rate became

significantly higher compared to non-irradiated cells in the

MT-CO1-downregulated cells 5 days after 7-Gy irradiation

(P<0.001). Although the survival rate kept decreasing in the

parent (TE4) cells, it increased in the RRCs

(MT-CO1-downregulated cells) at day 9. The difference

between the parent cells and RRCs increased, with survival rates at

day 9 of 10.5 and 28.7%, respectively (P<0.001).

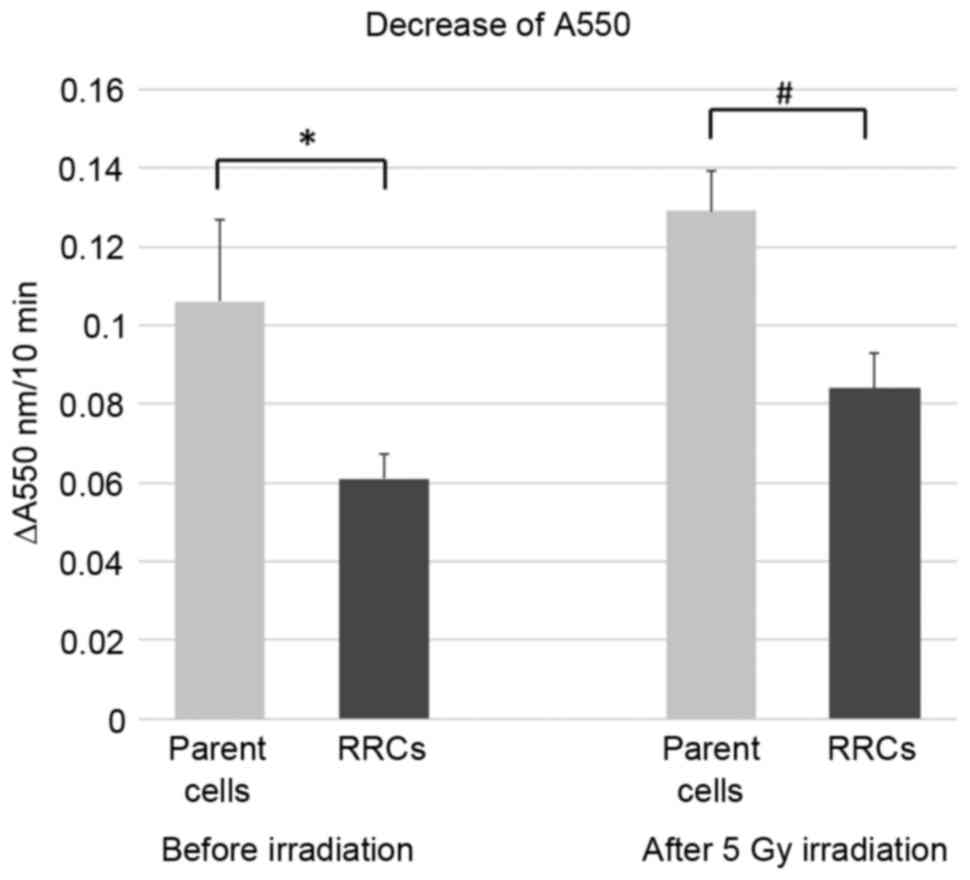

The activation of cytochrome c oxidase

was inhibited in RRCs

The cytochrome c oxidase changed reduced

cytochrome c (ferrochrome c) into oxidized cytochrome

c (ferrichrome c). Cytochrome c has a sharp

absorption band at 550 nm in the reduced state. Activation of

cytochrome c oxidase was measured as a decrease in

absorbance at 550 nm after adding cytochrome c reduced by

DTT.

Fig. 3 shows the

decrease in the absorbance at 550 nm, which was 0.106 in the parent

(TE4) cells and 0.061 in the RRCs before irradiation. Six h after

5-Gy irradiation, the decrease in absorbance was 0.129 in the

parent cells and 0.084 in the RRCs. Activation of cytochrome

c oxidase was significantly lower in RRCs with MT-CO1

downregulation both before and after irradiation (P=0.023 and

P=0.005, respectively).

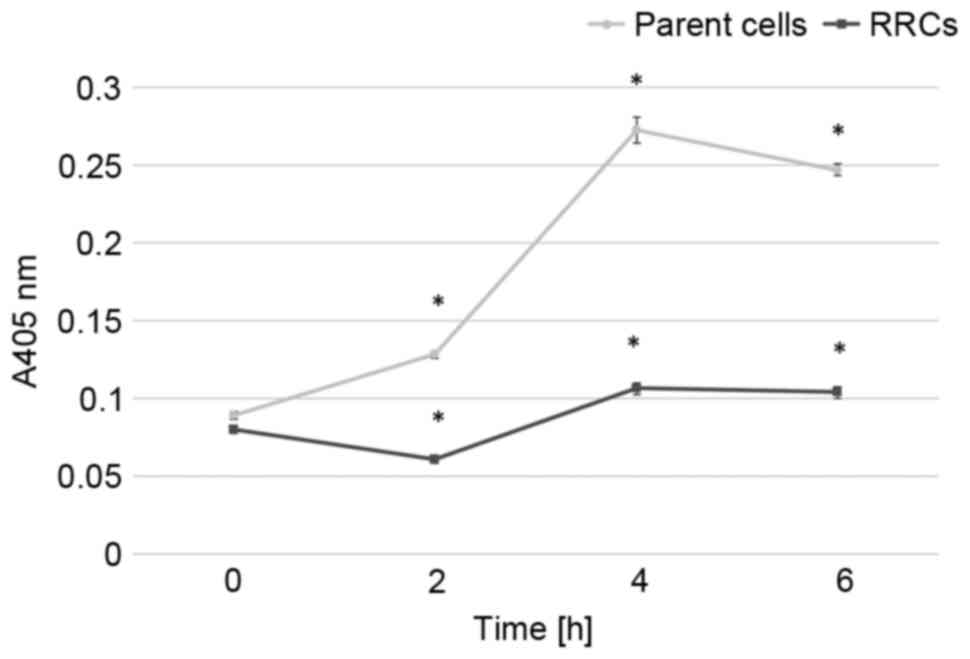

The activation of caspase-3 was

inhibited in RRCs after irradiation

To show that activation of the caspase cascade

induced by oxidized cytochrome c was suppressed in RRCs

after irradiation, we measured the activity of caspase-3.

Caspase-3 activity after 5-Gy irradiation is shown

in Fig. 4. In the parent cells,

caspase-3 activity rapidly increased after irradiation and reached

its peak at 4 h after the irradiation. Caspase-3 activity gradually

increased after irradiation in the RRCs, although it remained

significantly lower than in the parent cells (P<0.001).

Discussion

We detected MT-CO1 as a candidate

radioresistant gene from radioresistant transposon-tagged

esophageal squamous cancer cells. Downregulation of MT-CO1

was verified by real-time quantitative PCR analysis of RRCs. RRCs

with the downregulation of MT-CO1 showed higher survival

rates than parent cells after irradiation. We also showed that

inhibiting apoptosis by the activation of caspase cascade caused

radioresistance because the activity of cytochrome c and

caspase-3 after irradiation was significantly lower in the

MT-CO1-downregulated RRCs.

MT-CO, or complex IV, is the terminal complex

of the electron transport chain on the mitochondrial membrane. It

is composed of three catalytic subunits encoded in mtDNA (subunits

1 to 3) and 10 accessory subunits (subunits 4 to 13) encoded in

nuclear DNA (7,8).

It is known that cytochrome c oxidase is

related to apoptosis (9). Cytochrome

c, released from mitochondria into the cytosol by various

apoptotic stimuli, binds to Apaf-1 and forms the apoptosome

which, in turn, activates pro-caspase-9 leading to apoptosis

(10). The redox state of cytochrome

c is important in this caspase-dependent apoptosis. Only

oxidized cytochrome c can activate the apoptosome, whereas

reduced cytochrome c cannot (11–13). The

most potent enzyme that oxidizes cytochrome c is cytochrome

c oxidase (13). Multiple

caspase-dependent and -independent cell death pathways induce

apoptosis after DNA damage (14). Our

results revealed that downregulation of the MT-CO1 gene could not

activate casepase-3 in a few hours after irradiation. It seemed to

affect radioresistant, high survival rate in 5 to 9 days after

irradiation, in our study.

The relationship between cytochrome c oxidase

and chemo or radioresistance has been reported in various tumor

cell lines (15–19). Comprehensive gene analysis on a

microarray in cervical carcinoma cells (squamous cell carcinoma)

showed that MT-CO1 was increased by a factor greater than

two in RRCs compared with radiosensitive cells (15). Also, in human acute myelogenic

leukemia cells, MT-CO3 was upregulated in chemoresistant

cells compared with in chemosensitive cells (16). However, these study did not verify

that overexpression of MT-CO1 actually induces

radioresistance. Because the technique for transfection into

mitochondrial DNA has not yet been established, it is impossible to

overexpress or downregulate a mitochondrial gene (17). Aichler et al (18) reported that knockdown of

MT-CO7A2 with siRNA increased chemosensitivity after

chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-flurouracil in esophageal

adenocarcinoma cells. Oliva et al (19,20)

revealed that pharmacologic and genetic manipulation of cytochrome

c oxidase restored chemosensitivity in chemoresistant glioma

cells. From these and our results, cytochrome c oxidase

seems to be a significant gene which induces chemo or

radioresistance, and it may be a target gene for treatment to

improve chemo or radiosensitivity.

A question raised by our study is about the

homogeneity of mtDNA. Each cell contains hundreds to thousands of

copies of mtDNA, so if a transposon transports into the

MT-CO1 gene in one mtDNA, it should not affect the

properties of the whole cell. However, in this study MT-CO1

was actually downregulated in RRCs. It is known that, in general,

all copies of mtDNA are identical within a cell, a genetic state

known as homoplasmy (21). In cell

proliferation, only one mtDNA is copied by rolling circle DNA

replication (22). Although this

mechanism has not yet been completely clarified, homoplasmy of

mtDNA could relate to the downregulation of MT-CO1.

It was unclear whether MT-CO1 gene mutation

was actually related to radioresistance in patients with esophageal

cancer. Multiple gene mutations with complicated interactions could

induce radioresistance. Although our comprehensive gene screening

is ongoing, it is proving to be a useful approach for detecting

radioresistant genes. Verification of the relationships between all

the detected radioresistant genes and the clinical responses to

radiation therapy is essential for clinical application.

In conclusion, eleven candidate radioresistant genes

in esophageal squamous cancer were detected by comprehensive gene

screening with transposons. The mechanism for radioresistance

induced by MT-CO1 downregulation was also revealed. The

candidate genes were detected under conditions more similar to a

clinical setting than was the case in previous forms of gene

screening. By detecting all radioresistant genes and revealing the

underlying mechanisms for this, we can select the appropriate

therapy for patients or enhance the effect of the therapy by

treating target genes.

References

|

1

|

Ishida K, Ando N, Yamamoto S, Ide H and

Shinoda M: Phase II study of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with

concurrent radiotherapy in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the

esophagus: A Japan Esophageal Oncology Group (JEOG)/Japan Clinical

Oncology Group trial (JCOG9516). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 34:615–619.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Guo W and Jiang YG: Current gene

expression studies in esophageal carcinoma. Curr Genomics.

10:534–539. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fukuda K, Sakakura C, Miyagawa K, Kuriu Y,

Kin S, Nakase Y, Hagiwara A, Mitsufuji S, Okazaki Y, Hayashizaki Y

and Yamagishi H: Differential gene expression profiles of

radioresistant oesophageal cancer cell lines established by

continuous fractionated irradiation. Br J Cancer. 91:1543–1550.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ogawa R, Ishiguro H, Kuwabara Y, Kimura M,

Mitsui A, Mori Y, Mori R, Tomoda K, Katada T, Harada K and Fujii Y:

Identification of candidate genes involved in the radiosensitivity

of esophageal cancer cells by microarray analysis. Dis Esophagus.

21:288–297. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen L, Stuart L, Ohsumi TK, Burgess S,

Varshney GK, Dastur A, Borowsky M, Benes C, Lacy-Hulbert A and

Schmidt EV: Transposon activation mutagenesis as a screening tool

for identifying resistance to cancer therapeutics. BMC Cancer.

13:932013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tsutsui M, Kawakubo H, Hayashida T, Fukuda

K, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, Wada N, Saikawa Y, Omori T, Takeuchi H

and Kitagawa Y: Comprehensive screening of genes resistant to an

anticancer drug in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol.

47:867–874. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kadenbach B, Jarausch J, Hartmann R and

Merle P: Separation of mammalian cytochrome c oxidase into

13 polypeptides by a sodium dodecyl sulfate-gel electrophoretic

procedure. Anal Biochem. 129:517–521. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Weishaupt A and Kadenbach B: Selective

removal of subunit VIb increases the activity of cytochrome

c oxidase. Biochemistry. 31:11477–11481. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pradelli LA, Bénéteau M and Ricci JE:

Mitochondrial control of caspase-dependent and -independent cell

death. Cell Mol Life Sci. 67:1589–1597. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Brown GC and Borutaite V: Regulation of

apoptosis by the redox state of cytochrome c. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1777:877–881. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pan Z, Voehringer DW and Meyn RE: Analysis

of redox regulation of cytochrome c-induced apoptosis in a

cell-free system. Cell Death Differ. 6:683–688. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Suto D, Sato K, Ohba Y, Yoshimura T and

Fujii J: Suppression of the pro-apoptotic function of cytochrome

c by singlet oxygen via a haem redox state-independent

mechanism. Biochem J. 392:399–406. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Borutaite V and Brown GC: Mitochondrial

regulation of caspase activation by cytochrome oxidase and

tetramethylphenylenediamine via cytosolic cytochrome c redox

state. J Biol Chem. 282:31124–31130. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kim R, Emi M and Tanabe K:

Caspase-dependent and -independent cell death pathways after DNA

damage (Review). Oncol Rep. 14:595–599. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Achary MP, Jaggernauth W, Gross E, Alfieri

A, Klinger HP and Vikram B: Cell lines from the same cervical

carcinoma but with different radiosensitivities exhibit different

cDNA microarray patterns of gene expression. Cytogenet Cell Genet.

91:39–43. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang TS, Myklebust LM, Kjarland E,

Gjertsen BT, Pendino F, Bruserud Ø, Døskeland SO and Lillehaug JR:

LEDGF/p75 has increased expression in blasts from

chemotherapy-resistant human acute myelogenic leukemia patients and

protects leukemia cells from apoptosis in vitro. Mol Cancer.

6:312007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Inoue K, Nakada K, Ogura A, Isobe K, Goto

Y, Nonaka I and Hayashi JI: Generation of mice with mitochondrial

dysfunction by introducing mouse mtDNA carrying a deletion into

zygotes. Nat Genet. 26:176–181. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Aichler M, Elsner M, Ludyga N, Feuchtinger

A, Zangen V, Maier SK, Balluff B, Schöne C, Hierber L, Braselmann

H, et al: Clinical response to chemotherapy in oesophageal

adenocarcinoma patients is linked to defects in mitochondria. J

Pathol. 230:410–419. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Oliva CR, Nozell SE, Diers A, McClugage SG

III, Sarkaria JN, Markert JM, Darley-Usmar VM, Bailey SM, Gillespie

GY, Landar A and Griguer CE: Acquisition of temozolomide

chemoresistance in gliomas leads to remodeling of mitochondrial

electron transport chain. J Biol Chem. 285:39759–39767. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Oliva CR, Moellering DR, Gillespie GY and

Griguer CE: Acquisition of chemoresistance in gliomas is associated

with increased mitochondrial coupling and decreased ROS production.

PLoS One. 6:e246652011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lightowlers RN, Chinnery PF, Turnbull DM

and Howell N: Mammalian mitochondrial genetics: Heredity,

heteroplasmy and disease. Trends Genet. 13:450–455. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shibata T and Ling F: DNA recombination

protein-dependent mechanism of homoplasmy and its proposed

functions. Mitochondrion. 7:17–23. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|