Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma is a heterogeneous disease

affecting the regulation of multiple genes and proteins that

contribute to the strong proliferation and invasion of degenerated

melanocytes into the dermis and subsequent metastatic dissemination

of melanoma cells and progression of the disease (1).

Ultraviolet (UV) light exposure is considered an

important predisposing factor that triggers continuous

proliferation of certain melanocytes, which do not undergo

senescence, and therefore support the development of melanoma

(2). In melanocytes, UV light usually

induces pigmentation. In this case, proliferation and pigment

production is stimulated by UV-induced DNA damage to keratinocytes,

which subsequently secrete α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (αMSH)

(3). αMSH binds to the melanocortin 1

receptor, which is expressed on melanocytes (4). Additional research demonstrated that

UVB-induced DNA lesions also cause genetic mutations directly in

melanocytes, with C→T transitions at dipyrimidine sites (5).

However, recent findings revealed that the

photo-carcinogenesis pathway is more complex, with consequences in

which each of these processes, mediated by various cellular,

biochemical and molecular changes, are closely associated with each

other (6).

Although UVA is the most prevalent component of

solar UV radiation reaching the surface of the Earth, it mainly

causes skin photo-aging (solar elastosis), but it is less

carcinogenic compared to UVB radiation (7). By contrast, although UVB radiation only

constitutes a minor part of solar radiation, it is carcinogenic at

significantly lower doses compared with UVA radiation. UVB has a

direct mutagenic effect on DNA as it is maximally absorbed by this

primary chromophore (8). UV photon

energy absorption by DNA decreases constantly at longer wavelengths

(in the UVA range); therefore, UVB radiation is considered the

major cause of skin cancer (9,10).

Notably, Noonan et al (11)

reported that only a single dose of burning UV radiation to neonate

hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-transgenic mice is

necessary and sufficient to induce melanoma with a high incidence.

Although supported by several studies, the molecular mechanism of

melanoma induction by UV irradiation is not fully understood

(12,13).

Cyld was first identified as a gene

associated with familial cylindromatosis, a disease showing

multiple benign skin tumors that result from Cyld germline

mutations (usually nonsense or missense mutations) associated with

somatic mutations in dermal cells (loss of heterozygosity)

(14). In previous studies, the

expression and function of CYLD in malignant melanoma and basal

cell carcinoma has been analyzed (15,16). These

uncovered a new mechanism, revealing that the zinc-finger

transcription factor SNAIL1 drives melanoma cells to a mitogenic

and metastatic phenotype via downregulating the expression of

CYLD. Loss of CYLD paves the way for activation of p50/p52

subunits of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), resulting in stimulation of

the expression of genes, including cyclin D1 and N-cadherin

expression. The induced target genes consequently lead to enhanced

proliferation, migration and invasiveness of melanoma cells in

vitro, as well as tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

Notably, increased SNAIL1 expression and reduced CYLD levels are

inversely correlated with progression-free and overall survival of

melanoma patients (16). Thus, it was

shown that SNAIL1 has an important role in melanoma progression

(17) and that one of the molecular

mechanisms involved is the downregulation of CYLD. However, the

role of SNAIL1 and CYLD in melanocyte proliferation and migration,

as well as early malignant transformation, remains elusive.

In the present study, the effect of UVB radiation,

one of the major promoting factors for the development of skin

cancer, on SNAIL1 expression was investigated. Induced

signaling via the ERK-SNAIL1 axis in normal primary human

melanocytes, which reduces CYLD expression in UVB dependency, was

identified.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

The melanoma cell line Mel Ei was derived from a

primary cutaneous melanoma, and the melanoma cell line Mel Im was

isolated from metastasis. These cell lines were provided by

Professor Judith P. Johnson (Cancer Immunology, Ludwig-Maximilians

University, Munich, Germany) (18).

The cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium,

supplemented with penicillin (400 U/ml), streptomycin (50 µg/ml)

and 10% fetal calf serum (all Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt,

Germany). Primary normal human epidermal melanocytes (NHEMs) were

isolated and cultured as described in a previous study (18,19).

Melanocytes were cultivated in M2 medium (PromoCell GmbH,

Heidelberg, Germany). All cell lines were incubated at 37°C in an

8% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

NHEMs were treated with the chemical

mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase inhibitors PD98059 and UO126

[specific for MAP kinase kinase (MEK) 1 and MEK2; both Calbiochem;

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany] for 6 h. Control cells were

incubated with the vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide alone.

UVB radiation

UVB radiation of NHEMs seeded in M2 medium

(PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) without PMA was performed with

defined UVB doses (Whatman Biometra Transilluminator; Biometra

GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). Kinase inhibitors were added before UVB

radiation at a concentration of 20 µM, and due to their light

sensitivity, renewed immediately after radiation in fresh medium at

a concentration of 10 µM. For quenching of singlet oxygen, cells

were treated with histidine (50 mM in PBS) 1 h prior to and during

UVB administration (80 mJ/cm2). The irradiated cells

were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 3 h

(Mel Ei cells) and 5 h (NHEMs).

Expression analysis

Isolation of total cellular RNA from the Mel Ei, Mel

Im cell lines and primary NHEM was performed using the E.Z.N.A.

MicroElute Total RNA kit (Omega Bio-Tek, VWR Darmstadt, Germany)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentration was

measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) and cDNA was

generated by reverse transcription using the Super Script II

Reverse Transcriptase kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific. Inc., Waltham,

MA, USA), with each reaction containing 500 ng of total RNA

according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Analysis of mRNA

expression was performed using quantitative Real-Time PCR on the

LightCycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

A volume of 1 µl cDNA template, 0.5 µl of forward and reverse

primers (each 20 µM) and 10 µl of SYBR Green I (Roche Diagnostics

GmbH) were combined to a total volume of 20 µl. Specific primers

for CYLD, cyclin D1, N-cadherin and SNAIL1 expression analysis are

summarized in Table I. The

housekeeping gene was β-actin (Table

I).

| Table I.Primer sequences for expression

analysis of cyclin D1, CYLD, N-cadherin, SNAIL and β-actin. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for expression

analysis of cyclin D1, CYLD, N-cadherin, SNAIL and β-actin.

| Gene | Primer

sequence |

|---|

| Cyclin D1 | F:

5′-GCCTGTGATGCTGGGCACTTCATC-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-TTTGGTTCGGCAGCTTGCTAGGTG-3′ |

| CYLD | F:

5′-TGCCTTCCAACTCTCGTCTTG-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-AATCCGCTCTTCCCAGTAGG-3′ |

| N-cadherin | F:

5′-TGGATGAAGATGGCATGG-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-AGGTGGCCACTGTGCTTAC-3′ |

| SNAIL | F:

5′-AGGCCCTGGCTGCTACAAG-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-ACATCTGAGTGGGTCTGGAG-3′ |

| β-actin | F:

5′-CTACGTCGCCCTGGACTTCGAGC-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-GATGGAGCCGCCGATCCACACGG-3′ |

Protein analysis

Protein extraction, analysis and western blotting

were performed as previously described (20), applying the following primary

antibodies: Polyclonal anti-CYLD [cat. no. 4495; dilution, 1:1,000;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA; (21)], anti-p44/42 MAP kinase (cat. no. 9102;

dilution, 1:1,000) or anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (cat. no.

4370; dilution, 1:1,000; both Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and

anti- β-actin (cat. no. A5441; dilution, 1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA).

Transfection/transduction of cell

lines

To express p65 and an adenoviral negative form of

IκB (AdVdnIκB) (22), melanoma cells

were transiently transfected or transduced with the expression

plasmid or adenovirus, respectively as previously described

(23).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed on at least 3

independent occasions. Results are presented as the mean ± standard

error of the mean (SEM). Comparison between groups was made using a

one-way analysis of variance followed by a Kruskal-Wallis test, and

comparisons between CYLD expression in NHEM cells with and without

UVB exposure were calculated by unpaired Student's t-test. All

calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism 7 software

(GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

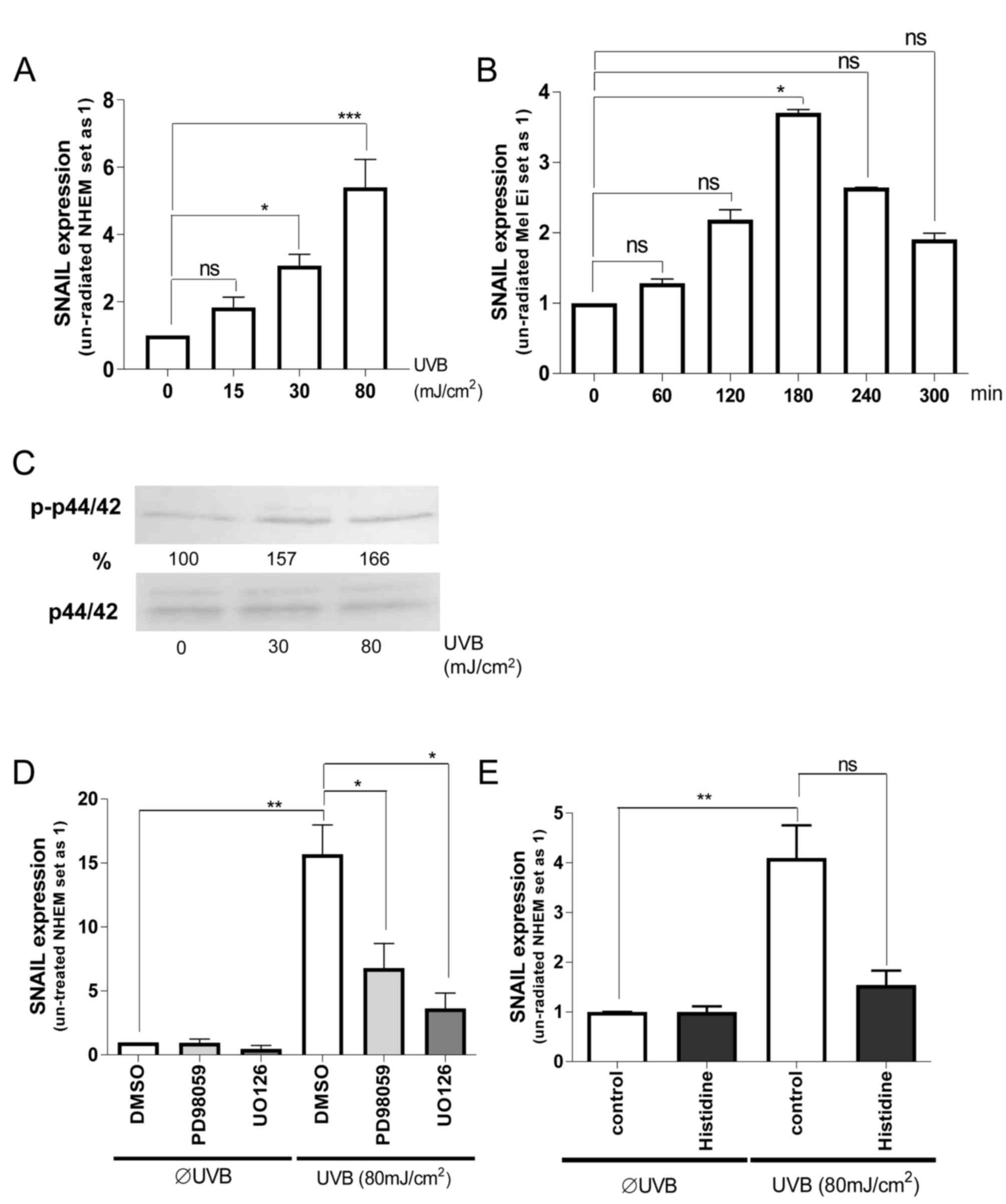

ERK and SNAIL regulation by UVB

irradiation in melanocytes

As the processes of proliferation and migration in

melanocytes have a physiological as well as pathophysiological

role, the present study determined whether there is an association

between UVB radiation exposure and expression of ERK and SNAIL1 in

melanocytes. It was identified that UVB-radiation induced

SNAIL1 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner in NHEMs;

the most effective dose was 80 mJ/cm2 (Fig. 1A). This induction was also observed in

the primary melanoma Mel Ei cells using the most effective UVB dose

of 80 mJ/cm2 (Fig. 1B). In

the present study, it was further revealed that the maximum SNAIL1

mRNA level was reached after 180 min of UVB radiation,

demonstrating a fast regulation of transcription.

To determine the mechanism of this UVB mediated

SNAIL expression, ERK signaling was first concentrated on.

Dose-dependent ERK activation by UV radiation in melanocytes was

identified (Fig. 1C). Pretreatment of

NHEMs with ERK-inhibitors (UO126 or PD98059) (Fig. 1D) significantly inhibited UVB

induction of SNAIL1 expression, although the base level was

not completely reached.

To determine the role of UV-induced reactive oxygen

species (ROS), NHEMs were pretreated with histidine (quencher to

inhibit the formation of free radicals) prior to UV irradiation.

Notably, histidine treatment almost completely inhibited UVB

effects on SNAIL1 expression (Fig.

1E). This indicates that UVB can induce SNAIL1

expression in NHEMs via free radical-mediated ERK activation.

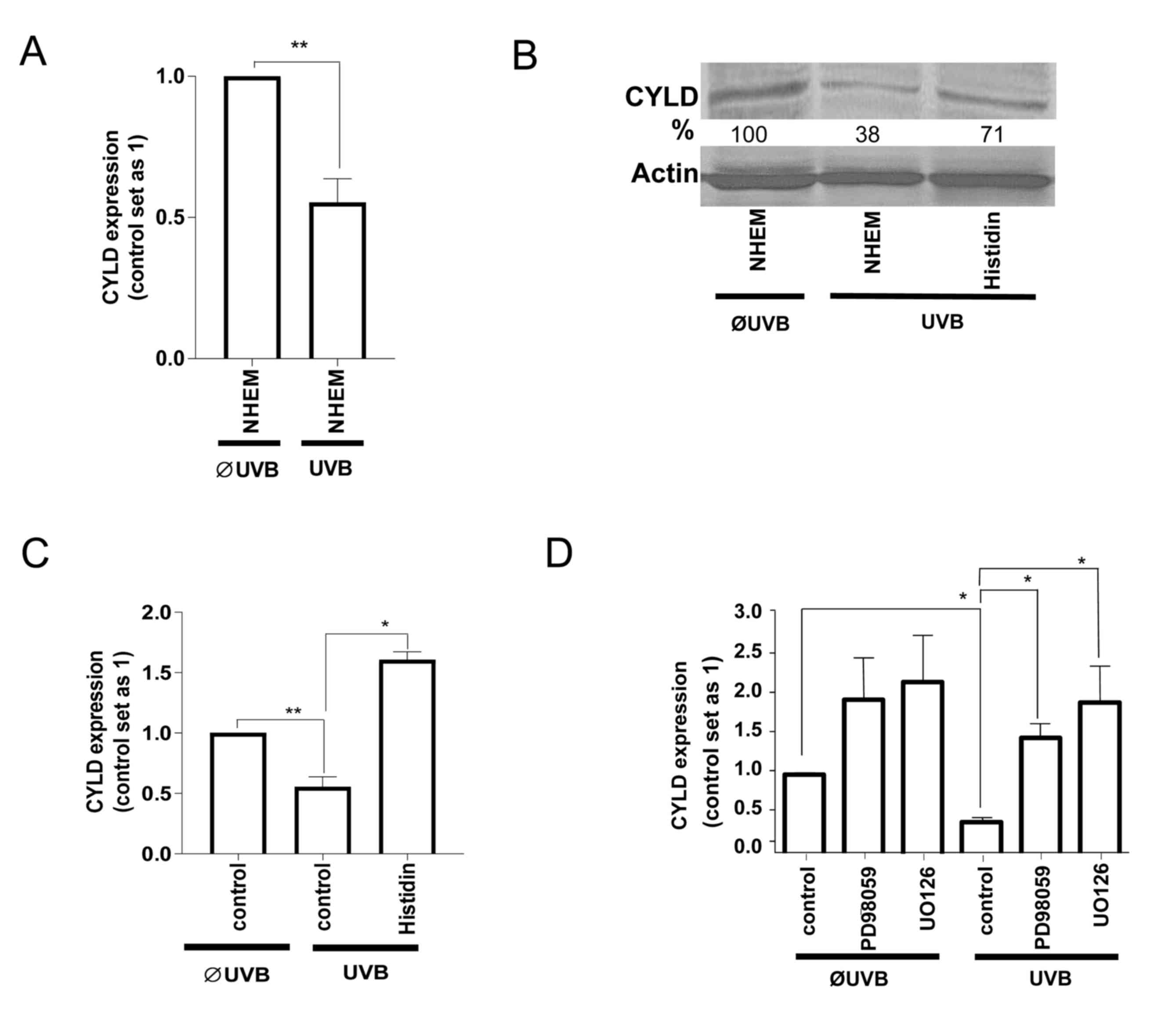

CYLD regulation by UVB irradiation in

melanocytes

Since SNAIL1 inhibited CYLD expression in

melanoma cells (16), it was

investigated whether the UVB-induced increase in SNAIL1 also

affects CYLD levels in NHEMs or whether this is a cancer-specific

regulation. Notably, UVB-radiation also led to the downregulation

of CYLD mRNA (Fig. 2A) and protein

(Fig. 2B) levels in NHEMs. Treatment

with histidine (Fig. 2B and C) as

well as with ERK-inhibitors (Fig. 2D)

inhibited the UVB-induced downregulation of CYLD. These data

indicate that UVB-induces ERK activation, and as a consequence,

SNAIL1 expression led to the downregulation of CYLD in non-tumorous

melanocytes similar, to the regulation found in malignant melanoma

cells.

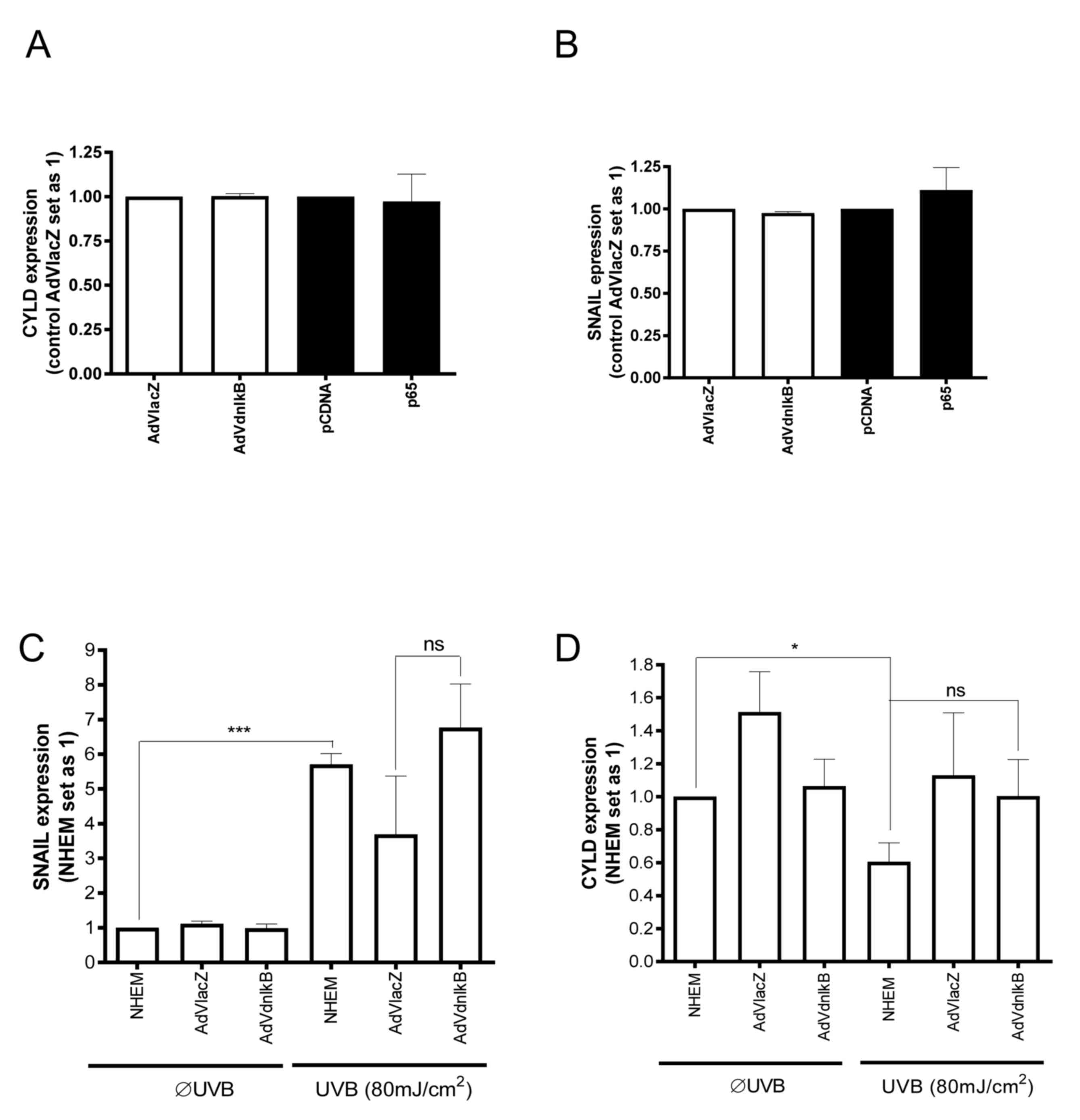

NF-κB involvement in the UVB dependent

signaling cascade in melanocytes

As previous studies have suggested that SNAIL1 is a

possible downstream target of NF-κB (24), the present study further explored the

role of this signaling pathway on SNAIL1 and CYLD expression in

NHEMs and melanoma cells. Adenoviral transduction of a dominant

negative form of IκB (AdVdnIκB) (25)

into Mel Im melanoma cells was performed, and the Mel Im cells were

transiently transfected with a p65 (NF-κB subunit) expression

plasmid. Neither SNAIL1 nor CYLD mRNA expression were

significantly affected by p65 overexpression or AdVdnIκB (Fig. 3A and B). Expression of a

dominant-negative form of IκB also failed to inhibit UVB-induced

SNAIL1 expression in NHEMs (Fig.

3C). Furthermore, inhibition of the NF-κB pathway did not

significantly affect UV-mediated CYLD expression in NHEMs (Fig. 3D). Based on these data, it was

concluded that UV-dependent downregulation of CYLD expression in

NHEMs is not mediated by the NF-κB pathway, but rather by the

ROS/ERK/SNAIL1 axis.

Discussion

UV-radiation is as an initiating factor in nevus

formation. On the basis of the anatomical distribution of acquired

nevi and a UV-associated mutation signature in the majority of the

somatic mutations of nevi, it is hypothesized that UV radiation

also contributes to melanoma initiation (4,9).

When pigment cells undergo neoplastic

transformation, these pathological derivatives are usually termed

according to the pigment that characterized the original cell

lineage, such as melanoma cells from melanocytes. Melanoma can

arise spontaneously in a variety of animals, including dogs,

horses, pigs and several fish. However, melanoma can also be

induced by exposure to UV irradiation and carcinogens, or by the

presence of relevant genetic changes in melanocytes (26). In previous years, varieties of genetic

changes have been characterized in human melanocytic neoplasms and

often correlate strongly with specific morphological

characteristics (4). While progress

has been made on defining the genetic changes present in melanoma,

much remains to be learned about the specific characteristics of

early malignant transformation of the melanocytes. As an example,

approximately one-half of all melanomas in humans harbor oncogenic

mutations in the BRAF gene (e.g., V600E), which leads to

constitutive activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK (p44/p42; MAPK)

signaling pathway (4,27). In contrast to melanoma cells,

melanocytes exhibit low ERK-activity and the question of which

early processes provoke pathological processes in melanocytes

remains.

Epidemiological studies indicate the importance of

UV radiation in the etiology of melanoma, and since UV-associated

mutations are relatively rare in melanoma, it was speculated that

UV radiation may support melanoma development by indirect effects

(28,29). As a physiological response,

melanocytes migrate to skin areas exposed to solar radiation, and

start to proliferate and produce melanin, thereby exhibiting their

protective effect against UV radiation (30). The signaling molecules involved in the

stimulation of migration and proliferation of melanocytes following

UV exposure remain unclear. However, the present study demonstrated

that UVB radiation induces ERK-activity in melanocytes (NHEMs),

similarly as previously shown in keratinocytes and melanoma cells

(31,32). Additionally, UVB radiation triggered

ERK-mediated SNAIL1 induction and downregulation of CYLD

expression in NHEMs. Following malignant transformation,

constitutive high ERK activity and SNAIL1 expression allow melanoma

cells permanently to exploit this mechanism to obtain a more

aggressive phenotype (16,17,23).

Previously, UVB light was identified as a trigger

for direct association of CYLD with B-cell lymphoma-3 (BCL-3)

(21). Following this association,

CYLD removes lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin chains from BCL-3,

which in turn prevents BCL-3 from translocating into the nucleus

and further expressing different genes in keratinocytes (21). It was observed in malignant melanoma

that loss of CYLD also induces nuclear accumulation of BCL-3 and

NF-κB activation, with the consequence of induced N-cadherin

(migration) and cyclin D1 (proliferation) activity (16). Data from embryogenesis and studies in

Drosophila (24,33–35),

suggesting that SNAIL1 is regulated by Dorsal (NF-κB), were

reassessed in the present study. However, it was found that in

melanoma ERK signaling appears to be the major pathway responsible

for the high constitutive activation of SNAIL1. While the migration

and proliferation of melanocytes in response to UV are

physiological with regards to skin protection by melanin,

long-lasting UV radiation, which is considered as one of the main

risk factors for the development of melanoma, may shift these cells

towards malignant transformation. In normal epidermal melanocytes,

UVB radiation induces ERK-activation and subsequently upregulates

SNAIL1 expression. The repression of CYLD by SNAIL1 allows

degeneration of melanocytes.

In melanoma cells, constitutively high ERK-activity

(potentially caused by B-RAF mutations) leads to high SNAIL1

expression, which in turn causes a high and strong suppression of

CYLD. Activation of cyclinD1 and N-cadherin leads to an increased

proliferation rate of melanoma cells and contributes to the

progression and metastasis of tumors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the technicians Mrs.

Lisa Ellmann (University Hospital, Regensburg, Germany) and Mrs.

Nadja Schneider (Friedrich-Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany)

for technical assistance. This study was supported by grants from

the German Research Foundation to S.K., C.H. and A.B. within the

research consortium (grant no. FOR2172).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

UVB

|

ultraviolet B

|

|

SNAIL1

|

snail family transcriptional repressor

1

|

|

NHEMs

|

normal human epidermal melanocytes

|

|

ERK

|

extracellular signal-regulated

kinase

|

References

|

1

|

Rowe CJ and Khosrotehrani K: Clinical and

biological determinants of melanoma progression: Should all be

considered for clinical management? Australas J Dermatol.

57:175–181. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Qadir MI: Skin cancer: Etiology and

management. Pak J Pharm Sci. 29:999–1003. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY,

Wilensky DL, Igras VE, D'Orazio J, Fung CY, Schanbacher CF, Granter

SR and Fisher DE: Central role of p53 in the suntan response and

pathologic hyperpigmentation. Cell. 128:853–864. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bastian BC: The molecular pathology of

melanoma: An integrated taxonomy of melanocytic neoplasia. Annu Rev

Pathol. 9:239–271. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Premi S, Wallisch S, Mano CM, Weiner AB,

Bacchiocchi A, Wakamatsu K, Bechara EJ, Halaban R, Douki T and

Brash DE: Photochemistry. Chemiexcitation of melanin derivatives

induces DNA photoproducts long after UV exposure. Science.

347:842–847. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nishisgori C: Current concept of

photocarcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 14:1713–1721. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

de Gruijl FR: Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs

UVB. Methods Enzymol. 319:359–366. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tornaletti S and Pfeifer GP: UV damage and

repair mechanisms in mammalian cells. Bioessays. 18:221–228. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Seebode C, Lehmann J and Emmert S:

Photocarcinogenesis and Skin Cancer Prevention Strategies.

Anticancer Res. 36:1371–1378. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

De Fabo EC, Noonan FP, Fears T and Merlino

G: Ultraviolet B but not ultraviolet A radiation initiates

melanoma. Cancer Res. 64:6372–6376. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Noonan FP, Recio JA, Takayama H, Duray P,

Anver MR, Rush WL, De Fabo EC and Merlino G: Neonatal sunburn and

melanoma in mice. Nature. 413:271–272. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Halliday GM, Agar NS, Barnetson RS,

Ananthaswamy HN and Jones AM: UV-A fingerprint mutations in human

skin cancer. Photochem Photobiol. 81:3–8. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini

P, Picconi O, Boyle P and Melchi CF: Meta-analysis of risk factors

for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure. Eur J Cancer. 41:45–60.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, Takahashi M,

Rapley E, Barfoot R, Green H, Brown C, Biggs PJ, Lakhani SR, et al:

Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor

gene. Nat Genet. 25:160–165. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kuphal S, Shaw-Hallgren G, Eberl M, Karrer

S, Aberger F, Bosserhoff AK and Massoumi R: GLI1-dependent

transcriptional repression of CYLD in basal cell carcinoma.

Oncogene. 30:4523–4530. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Massoumi R, Kuphal S, Hellerbrand C, Haas

B, Wild P, Spruss T, Pfeifer A, Fässler R and Bosserhoff AK:

Down-regulation of CYLD expression by Snail promotes tumor

progression in malignant melanoma. J Exp Med. 206:221–232. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kuphal S, Palm HG, Poser I and Bosserhoff

AK: Snail-regulated genes in malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res.

15:305–313. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Munker R, Johnson J,

Petersmann I, Schmoeckel C and Riethmuller G: In vitro

differentiation of human melanoma cells analyzed with monoclonal

antibodies. Cancer Res. 45:1344–1350. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsuji T and Karasek M: A procedure for the

isolation of primary cultures of melanocytes from newborn and adult

human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 81:179–180. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Spangler B, Kappelmann M, Schittek B,

Meierjohann S, Vardimon L, Bosserhoff AK and Kuphal S: ETS-1/RhoC

signaling regulates the transcription factor c-Jun in melanoma. Int

J Cancer. 130:2801–2811. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Massoumi R, Chmielarska K, Hennecke K,

Pfeifer A and Fässler R: Cyld inhibits tumor cell proliferation by

blocking Bcl-3-dependent NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 125:665–677.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jobin C, Hellerbrand C, Licato LL, Brenner

DA and Sartor RB: Mediation by NF-kappa B of cytokine induced

expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) in an

intestinal epithelial cell line, a process blocked by proteasome

inhibitors. Gut. 42:779–787. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kuphal S, Poser I, Jobin C, Hellerbrand C

and Bosserhoff AK: Loss of E-cadherin leads to upregulation of

NFkappaB activity in malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 23:8509–8519.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Barberà MJ, Puig I, Domínguez D,

Julien-Grille S, Guaita-Esteruelas S, Peiró S, Baulida J, Francí C,

Dedhar S, Larue L, et al: Regulation of Snail transcription during

epithelial to mesenchymal transition of tumor cells. Oncogene.

23:7345–7354. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hellerbrand C, Jobin C, Iimuro Y, Licato

L, Sartor RB and Brenner DA: Inhibition of NFkappaB in activated

rat hepatic stellate cells by proteasome inhibitors and an IkappaB

super-repressor. Hepatology. 27:1285–1295. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Schartl M, Larue L, Goda M, Bosenberg MW,

Hashimoto H and Kelsh RN: What is a vertebrate pigment cell?

Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 29:8–14. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Guadarrama-Orozco JA, Ortega-Gómez A,

Ruiz-García EB, Astudillo-de la Vega H, Meneses-García A and

Lopez-Camarillo C: Braf V600E mutation in melanoma: Translational

current scenario. Clin Transl Oncol. 18:863–871. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Brenner M, Degitz K, Besch R and Berking

C: Differential expression of melanoma-associated growth factors in

keratinocytes and fibroblasts by ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B

radiation. Br J Dermatol. 153:733–739. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jhappan C, Noonan FP and Merlino G:

Ultraviolet radiation and cutaneous malignant melanoma. Oncogene.

22:3099–3112. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Esparza-Soto M, Fox P and Westerhoff P:

Transformation of molecular weight distributions of dissolved

organic carbon and UV-absorbing compounds at full-scale

wastewater-treatment plants. Water Environ Res. 78:253–262. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pak BJ, Lee J, Thai BL, Fuchs SY, Shaked

Y, Ronai Z, Kerbel RS and Ben-David Y: Radiation resistance of

human melanoma analysed by retroviral insertional mutagenesis

reveals a possible role for dopachrome tautomerase. Oncogene.

23:30–38. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Peus D, Meves A, Vasa RA, Beyerle A,

O'Brien T and Pittelkow MR: H2O2 is required for UVB-induced EGF

receptor and downstream signaling pathway activation. Free Radic

Biol Med. 27:1197–1202. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ip YT: Transcriptional regulation.

Converting an activator into a repressor. Curr Biol. 5:1–3. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ip YT, Park RE, Kosman D, Yazdanbakhsh K

and Levine M: dorsal-twist interactions establish snail expression

in the presumptive mesoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev.

6:1518–1530. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Marchal L, Foucaul A, Patissier G, Rosant

JM and Legrand J: Influence of flow patterns on chromatographic

efficiency in centrifugal partition chromatography. J Chromatogr A.

869:339–352. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|