Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies

globally and a major cause of cancer-associated mortality in women

(1). Cisplatin (DDP) is the first

line chemotherapeutic drug for solid tumor types, including breast

cancer. However, DDP resistance is one of the current challenges

facing the management of breast cancer patients. DDP primarily acts

to form complexes with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), leading to

mitochondria damage and concomitant cell death through the

intrinsic apoptosis pathway (2,3).

Furthermore, DDP reduces mtDNA copies and increases the sensitivity

of tumor cells to chemotherapy (4).

Thus, dysregulation of mtDNA copy number and gene expression may be

associated with the progression and prognosis of breast cancer

following DDP treatment.

Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) drives

the transcription and replication of mtDNA and is involved in the

regulation of mtDNA copies and the maintenance and repair of

mitochondrial genes (5). Therefore,

TFAM is important in terms of the functional integrity of the

mitochondrial respiratory chain and the maintenance of balance

between anti-oxidation and oxidation (5). Nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) may

bind to the promoter of the TFAM gene to regulate TFAM expression,

and may be involved the biogenesis and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

production in mitochondria (6,7).

NRF1 and TFAM expression has been demonstrated to be

associated with the clinical features of certain tumor types,

including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal, liver and

bladder cancer (8–11). NRF1 and TFAM mRNA and

protein expression have been demonstrated to be positive in

patients with breast cancer compared with adjacent normal patients

or in MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-453 cell lines compared with a

control Hs578T cell line (12,13), but

NRF1 and TFAM expression patterns in breast cancer

and adjacent normal tissues, as well as their clinical

significance, remain unclear. In the present study, breast cancer

tissues and adjacent normal tissues were collected from patients,

and immunohistochemistry array analysis of Nrf1 and TFAM protein

expression was performed. The results of the present study

demonstrated that Nrf1 and TFAM protein expression was increased in

the cancer cells of patients with different types of breast cancer,

and patients who were positive for Nrf1 and TFAM had a decreased

long-term survival rate compared with patients who were

negative.

Materials and methods

Patients

All patients with primary breast cancer who had

undergone initial surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of The

Second Military Medical University (Changhai Hospital, Shanghai,

China) between January 2009 and June 2010 were screened for

enrolment in the present study by reviewing electronic charts.

Patients who presented with other primary tumor sites or who

received preoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy were excluded. A

total of 388 patients were enrolled in the present study and 336

patients with complete clinical information were included for

further analysis. The following variables were recorded: Patient

age at diagnosis, menopausal status, largest tumor diameter, number

of lymph node metastases, tumor-node-metastasis stage (TNM, NCCN

Guidelines, Breast Cancer Version 3.2014) (14) and histologic grade.

Clinicopathological characteristics for these patients are detailed

in Table I. All tissue specimens used

in the present study were obtained with written informed consent

from the patients, and the Ethics Committee of Changhai Hospital

granted approval for this measure and the research protocol.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of patients

enrolled in the present study. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients

enrolled in the present study.

| Clinicopathological

variable | Value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range) | 53 (30–81) |

| Menopausal status

(%) |

|

|

Premenopausal | 152 (45.2) |

|

Postmenopausal | 184 (54.8) |

| TNM stage (%) |

|

| I | 104 (31.0) |

| II | 195 (58.0) |

|

III | 37 (11.0) |

| Pathological

diagnosis (%) |

|

|

Invasive ductal carcinoma | 312 (92.9) |

|

Non-invasive ductal

carcinoma | 24 (7.1) |

| Histological grade

(%) |

|

| 1 | 16 (4.8) |

| 2 | 216 (64.3) |

| 3 | 104 (30.9) |

| Erb-b2 receptor

tyrosine kinase 2 status (%) |

|

|

Negative | 280 (83.3) |

|

Positive | 56 (16.7) |

| Estrogen receptor

status (%) |

|

|

Negative | 152 (45.2) |

|

Positive | 184 (54.8) |

| Progesterone

receptor status (%) |

|

|

Negative | 198 (58.9) |

|

Positive | 138 (41.1) |

Tissue microarray (TMA) and

immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Large core TMAs were used in order to cover a larger

number of tumor cells and represent the typical pathological

changes, as described previously (15). Tissues were embedded in paraffin and

sectioned (4 µm thickness) for hematoxylin (4 min) and eosin (3

min) staining (25°C). Pathological examination was performed by an

experienced pathologist, and the region of interest was marked on

the basis of the HE staining results. Away from areas of ulceration

and necrosis, 1.5-mm diameter cylinders were punched from the

center of the excised tumor and re-embedded into a recipient

paraffin block, using a tissue-arraying instrument (Beecher

Instruments, Inc., Sun Prairie, WI, USA). The microarray sections

were randomly inspected, processed for HE staining and observed

under a light microscope for quality control. The TMA blocks were

then cut into 4-mm sections and processed for IHC.

Tissues were fixed in 4% neutral formalin at 4°C for

24 h and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were dewaxed and

washed with 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature for 15 min,

followed by further washing with double distilled water for 6 min

and PBS for 6 min. The microarray sections were put into the

microwave oven and heated until boiling in 0.01 mol/l sodium

citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) for 5 min, repeated 2 times, then

cooled at room temperature for 20 min, before being washed in PBS.

Sections were incubated in horse serum (10%) at room temperature

for 40 min. Sections were then incubated in PBS containing 1%

bovine serum albumin (pH 7.4) overnight followed by secondary

antibody. The TFAM (K-18′ cat. no. sc19050; goat anti-human) and

Nrf1 (h-300; cat no. 33771; rabbit anti-human) antibodies (Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) were used at final

dilutions of 1:100 and 1:1,000 overnight at 4°C respectively.

Immunostaining was conducted using the Dako EnVision System with

diaminobenzidine according to the manufacturer's protocol (Dako,

Glostrup, Denmark). AperioImageScope v11.2.2.752 software

(http://aperio-imagescope.software.Informer.com) was

used to capture images, which were then independently evaluated by

two experienced pathologists who were blind to the

clinicopathological factors of the patients in the present study.

Any discrepancy was resolved by consulting a third pathologist.

Semi-quantitative criteria

A semi-quantitative evaluation of Nrf1 and TFAM

positive staining in IHC was performed using a previously described

method (15). Briefly, five

representative images from IHC for Nrf1 and TFAM were captured from

each section at a high magnification (×200). The staining intensity

compared with the background and the percentage of positive cells

were determined in a blind manner. The percentage of positive cells

was divided into five grades (percentage scores): 0, <10; 1,

10–25; 2, 26–50; 3, 51–75; and 4, >75%. The intensity of

staining was divided into four grades (intensity scores): 0, no

staining; 1, light brown; 2, brown; and 3, dark brown. The total

scores (percentage score × intensity score) ranged from 0 to 12,

and were divided into low expression (0–2) or high expression

(3–12)

groups.

Clinicopathological parameters and

their classifications

Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor

(PR) status were classified thus: Cells positive for ER and PR had

immunoreactivity in the nuclei with or without cytoplasmic staining

in IHC. The nucleus was a major site where immunoreactivity existed

for ER and PR, and cells with only cytoplasmic immunoreactivity

were regarded as negative for ER or PR. ER and PR expression was

determined according to the percentage of positive cells: Negative,

≤10%; positive, >10%.

Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (HER2) protein

expression was assessed by IHC. Cells were regarded as positive for

HER2 when 3+ was noted in IHC or 2+ was present in IHC and

simultaneous positive staining was observed in fluorescence in

situ hybridization (FISH) (16).

FISH analysis was performed using the PathVysion HER-2 probe kit

(Abbott Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA). There were

two fluorescent-labelled probes: LSI (locus-specific identifier)

HER-2 specific for the HER-2 gene locus (17q11) and CEP (chromosome

enumeration probe) 17 specific for the α satellite DNA sequence at

the centromeric region of chromosome 17. Paraffin sections of 3–4

mm thickness using a microtome were cut and were floated in a

protein-free water bath at 40°C. The sections were mounted on

poly-L-Lysine coated slides and allowed to dry. The slides were

kept overnight at 56°C. The slides were deparaffinized in xylene at

room temperature for 20 min and dehydrated in 100% ethanol for 15

min at room temperature and air dried. The slides were treated with

pretreatment solution (sodium thiocyanite) and protease solution

for 15 min, and were dehydrated with 70, 80 and 100% alcohol for 5

min each and air dried. The probe was denatured at 80°C for 5 min,

applied to the cover slip and placed in humidified chamber for

overnight incubation. Post-hybridization washes were given with

0.4% sodium saline citrate 40 at 37°C. Following removal of the

cover slips the slides were dipped in post-hybridization buffer for

18 sec, dried completely in darkness and 10 µl DAPI was applied.

The slides were screened under a fluorescent microscope (Olympus

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using appropriate filters (DAPI, FITC,

TRITC dual and triple band pass filters). Signals were counted in

at least 200 cells for both the HER-2/neu gene and chromosome 17

centromere signals under oil immersion at ×1,000 magnification

using recommended filters. Results are expressed as the ratio of

HER-2/neu signal (orange) to centromere 17 signal (green) and the

readings were read as follows; the expected ratio 1–1.8 indicates

no gene amplification (negative), a ratio of >2.2 as HER-2/neu

gene amplification (positive), and a ratio between 1.8 and 2.2 as

equivocal cases. The polysomy 17 was also recorded in the cells as

four spec green signals as moderate polysomy and >4 spec green

signals as high polysomy.

Menopause was defined when one of following

conditions was present: i) patients received bilateral

oophorectomy; ii) patients were ≥60 years old; iii) patients were

<60 years old, but follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and

estradiol levels were in the postmenopausal range. The menopause

could not be determined in patients who were receiving luteinizing

hormone-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists, and amenorrhea

was not enough to determine menopause in premenopausal women

receiving adjunctive chemotherapy. Under these conditions, repeated

measurements of FSH and/or estradiol were required to determine

whether there was a menopausal status in these patients.

Histological grading was based on the

semiquantitative evaluation of three morphologic features

(percentage of tubule formation, degree of nuclear pleomorphism,

and accurate mitotic count in a defined field area) with a 3-point

grading system (1, good, to 3, poor). The numerical score assigned

to each feature was used in the compilation of an overall grade:

Scores 3–5, grade 1; scores 6–7, grade 2; scores 8–9, grade 3

(17).

The number of involved lymph nodes was scored thus:

1 involved lymph node, 1; 1–3 lymph nodes, 2; 4–9 lymph nodes, 3;

≥10 lymph nodes, 4.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and

GraphPad software (version 5.01; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla,

CA, USA) were used for statistical analysis and image processing,

respectively. The protein expression of Nrf1 and TFAM in breast

cancer tissues were compared with adjacent normal tissues using the

Wilcoxon rank sum test. Associations between Nrf1 and TFAM

expression and clinicopathological features were assessed using

Pearson's χ2 test. Multivariate analysis was performed

using logistic regression. Overall survival (OS) was measured from

the date of diagnosis until mortality or the last follow-up.

Patients alive were censored at the time of last contact. OS rates

were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the

log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was

performed for univariate and multivariate survival analysis.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Nrf1 and TFAM expression in breast

cancer and adjacent normal tissues

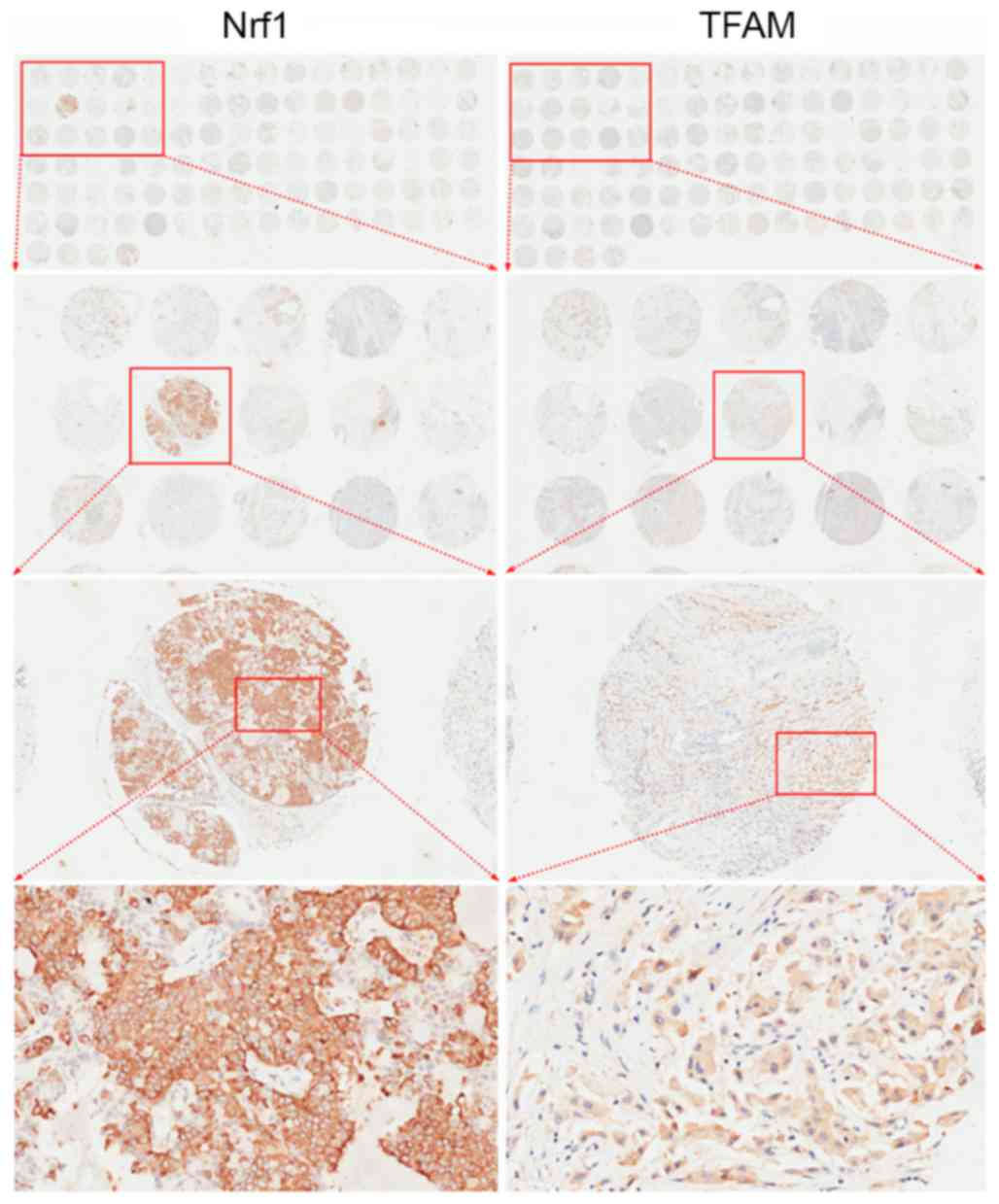

Nrf1 and TFAM protein expression was measured in 336

patients with TMAs. Fig. 1 presents

the arrangement of representative TMAs and images captured at

different magnifications following IHC analysis. Representative

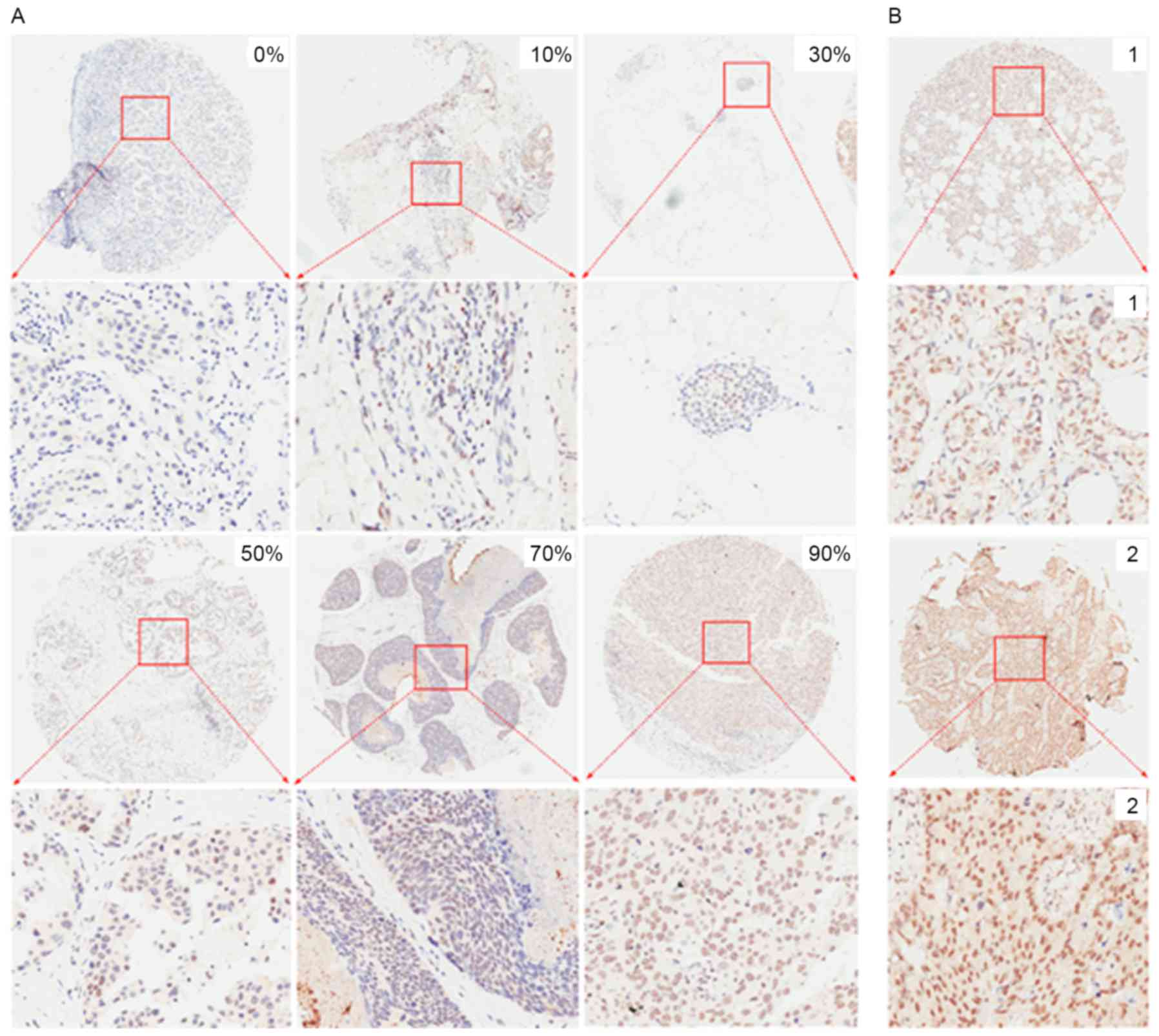

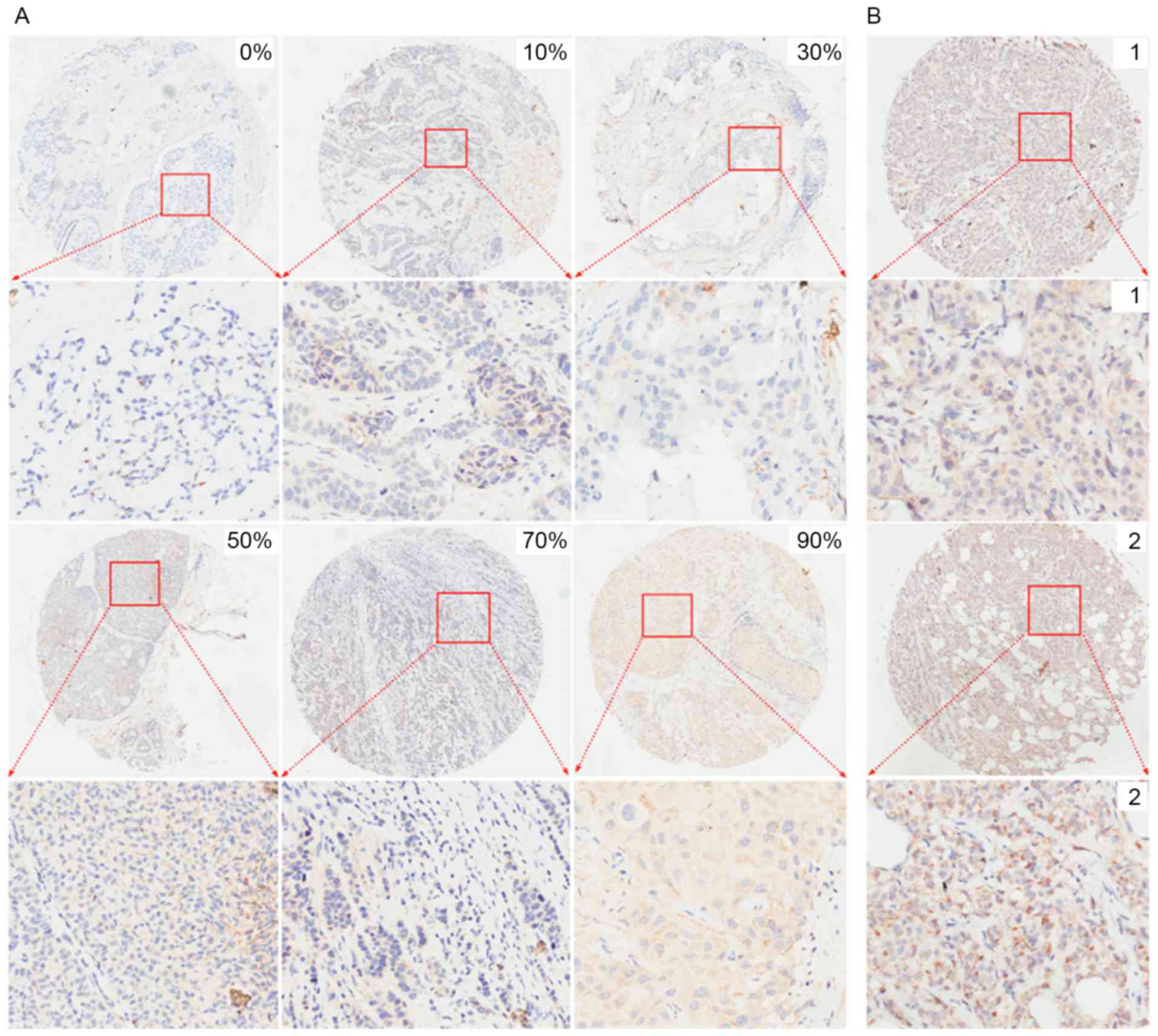

images with different percentages of positive cells and different

staining intensities captured following immunohistochemistry for

Nrf1 and TFAM are presented in Figs.

2 and 3, respectively. For

sections without positive cells (0%), the staining intensity was

also classified as 0. The majority of Nrf1-positive cells had brown

staining in the nuclei (Fig. 2) with

only a fraction of cancer cells expressing Nrf1 in the cytoplasm

(Fig. 1) or in the nuclei and

cytoplasm (data not shown). TFAM expression was observed in the

cytoplasm of breast cancer cells (Fig.

3).

The association between Nrf1 and TFAM expression was

evaluated in 336 patients. Paired χ2 tests revealed that

Nrf1 and TFAM expression were not significantly associated

(κ=0.057, P=0.258). The positive rate of Nrf1 expression was

significantly increased compared with TFAM in breast cancer cells

(75.3% compared with 57.1%; P<0.001). Nrf1 binds to the promoter

of TFAM to initiate TFAM expression (6,7). The

results of the present study demonstrated that the alteration of

Nrf1 expression was not parallel to that of TFAM in breast cancer

cells, suggesting that, besides Nrf1, there are additional

mechanisms regulating TFAM expression.

Nrf1 and TFAM expression is increased

in breast cancer tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues

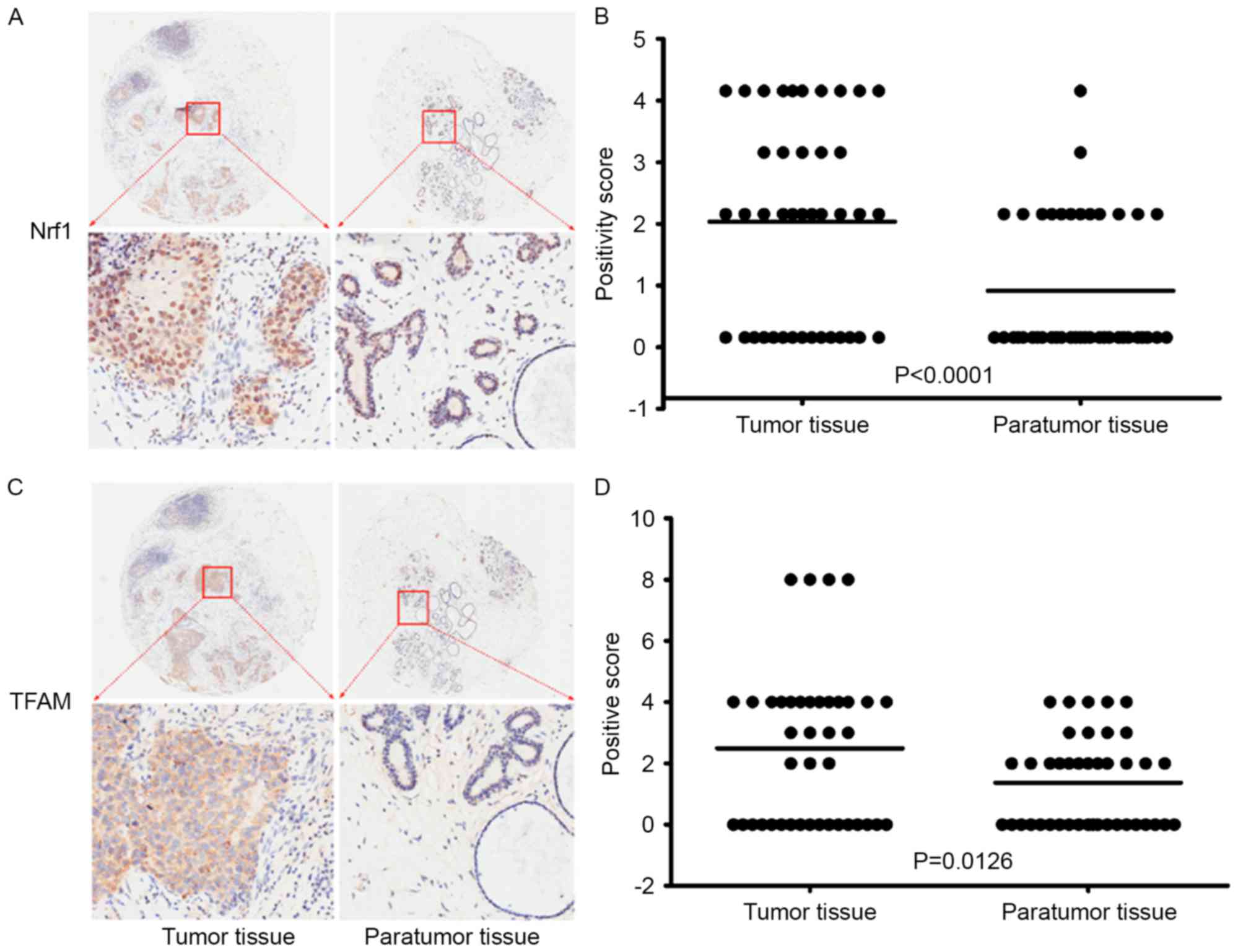

To investigate the involvement of Nrf1 and TFAM in

the occurrence and development of breast cancer, Nrf1 and TFAM

expression was compared in breast cancer tissues and in the

corresponding adjacent normal tissues from 41 patients (Table II). For Nrf1 positive cells, the mean

and median integrations were 1.878 [95% confidence interval (CI):

1.368–2.388] and 2.0 (25–75th percentile range: 0–3.5) in breast

cancer tissue, and 0.756 (95% CI: 0.405–1.107) and 0 (25–75th

percentile range: 0–2) in the adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 4A). Wilcoxon rank sum tests revealed

significant differences in the mean and median integrations between

breast cancer and adjacent normal tissues, with more Nrf1 positive

cells being observed in the breast cancer tissue compared with

normal tissues (P<0.0001; Fig.

4B). For TFAM-positive cells, the mean and median integrations

were 2.488 (95% CI: 1.686–3.290) and 3.0 (25–75th percentile range:

0–4) in the breast cancer tissue, and 1.366 (95% CI: 0.899–1.833)

and 2.0 (25–75th percentile range: 0–2) in the adjacent normal

tissues (Fig. 4C). Wilcoxon rank sum

tests revealed that the number of TFAM-positive cells in breast

cancer tissue was significantly higher than that in the adjacent

normal tissue (P=0.0126; Fig. 4D).

These results demonstrated that Nrf1 and TFAM protein expression

were significantly increased in breast cancer tissue compared with

adjacent normal tissues, suggesting that Nrf1 and TFAM may be

involved in the tumorigenesis of breast cancer and are potential

targets for the therapy of breast cancer.

| Table II.Clinical characteristics of the 41

patients where expression of Nrf1 and TFAM was evaluated in cancer

tissues and adjacent normal tissues. |

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of the 41

patients where expression of Nrf1 and TFAM was evaluated in cancer

tissues and adjacent normal tissues.

| Clinicopathological

variable | Value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range) | 54 (41–76) |

| Menopausal status

(%) |

|

|

Premenopausal | 13 (31.7) |

|

Postmenopausal | 28 (68.3) |

| TNM stage (%) |

|

| I | 19 (46.3) |

| II | 18 (13.9) |

|

III | 4 (9.8) |

| Pathological

diagnosis (%) |

|

|

Invasive ductal carcinoma | 35 (85.4) |

|

Non-invasive ductal

carcinoma | 6 (14.6) |

| Histological grade

(%) |

|

| 1 | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 28 (68.3) |

| 3 | 13 (31.7) |

| Erb-b2 receptor

tyrosine kinase 2 status (%) |

|

|

Negative | 33 (80.5) |

|

Positive | 8 (19.5) |

| Estrogen receptor

status (%) |

|

|

Negative | 36 (87.8) |

|

Positive | 5 (12.2) |

| Progesterone

receptor status (%) |

|

|

Negative | 37 (90.2) |

|

Positive | 4 (9.8) |

Association of Nrf1 and TFAM

expression with clinicopathological features of patients with

breast cancer

Next, the associations between Nrf1 and TFAM protein

expression and the clinicopathological features of patients with

breast cancer were analyzed (Table

III). The results revealed that Nrf1 expression was

significantly associated with age, tumor size, number of metastatic

lymph nodes, tumor stage, tumor grade and HER2, ER and PR

expression status, but there was no significant association with

menopause status or pathological type of breast cancer. Patients

<45 years old had significantly increased Nrf1 expression

compared with older patients (84.7 vs. 72.7%). Nrf1 expression in

patients with a tumor size >2 cm, more metastatic lymph nodes or

breast cancer at >TNM stage II or >grade 2 was significantly

increased. Patients positive for HER2, ER and PR had markedly

higher Nrf1 expression than patients negative for these

factors.

| Table III.Associations between Nrf1 and TFAM

expression and clinicopathological features. |

Table III.

Associations between Nrf1 and TFAM

expression and clinicopathological features.

|

| Nrf1 | TFAM |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathological

variable | Negative | Positive |

χ2/P-value | Negative | Positive |

χ2/P-value |

|---|

| Age at diagnosis,

years |

|

| 4.376/0.036 |

|

| 0.589/0.443 |

|

≤45 | 11 | 61 |

| 28 | 44 |

|

|

>45 | 72 | 192 |

| 116 | 148 |

|

| Menopausal

status |

|

| 2.769/0.096 |

|

| 0.001/0.975 |

|

Premenopausal | 31 | 121 |

| 65 | 87 |

|

|

Postmenopausal | 52 | 132 |

| 79 | 105 |

|

| Tumor size, cm |

|

|

25.925/<0.001 |

|

|

28.329/<0.001 |

| ≤2 | 40 | 80 |

| 54 | 66 |

|

|

2–5 | 36 | 148 |

| 63 | 121 |

|

| ≥5 | 7 | 25 |

| 27 | 5 |

|

| Lymph node

metastasis |

|

| 10.763/0.005 |

|

| 5.609/0.061 |

|

0–1 | 67 | 198 |

| 106 | 159 |

|

| 2 | 16 | 30 |

| 27 | 19 |

|

|

3–4 | 0 | 25 |

| 11 | 14 |

|

|

Tumor-node-metastasis stage |

|

|

35.243/<0.001 |

|

| 3.283/0.194 |

| I | 34 | 70 |

| 43 | 61 |

|

| II | 13 | 182 |

| 80 | 115 |

|

|

III | 5 | 32 |

| 21 | 16 |

|

| Pathological

diagnosis |

|

| 2.276/0.131 |

|

|

<0.001/1.000 |

|

Invasive ductal carcinoma | 74 | 238 |

| 135 | 180 |

|

|

Non-invasive ductal

carcinoma | 9 | 15 |

| 9 | 12 |

|

| Histology

grade |

|

| 2.157/0.034 |

|

| 2.379/0.304 |

| 1 | 6 | 10 |

| 4 | 12 |

|

| 2 | 49 | 167 |

| 89 | 127 |

|

| 3 | 28 | 76 |

| 47 | 57 |

|

| Erb-b2 receptor

tyrosine kinase 2 status |

|

| 5.379/0.020 |

|

| 5.600/0.018 |

|

Negative | 76 | 204 |

| 112 | 168 |

|

|

Positive | 7 | 49 |

| 32 | 24 |

|

| Estrogen receptor

status |

|

| 10.015/0.002 |

|

|

26.675/<0.001 |

|

Negative | 50 | 102 |

| 64 | 88 |

|

|

Positive | 33 | 151 |

| 80 | 104 |

|

| Progesterone

receptor status |

|

|

13.124/<0.001 |

|

|

35.754/<0.001 |

|

Negative | 63 | 135 |

| 87 | 111 |

|

|

Positive | 20 | 118 |

| 7 | 81 |

|

TFAM expression was also associated with the tumor

size and HER2, ER and PR status. Patients positive for HER2, ER and

PR had increased TFAM expression compared with those who were not,

while patients with tumor size of >2 cm had a slight reduction

in TFAM expression. These results indicated that Nrf1 and TFAM

expression is associated with factors associated with the clinical

outcome of patients with breast cancer, and thus may serve as

important predictors for patients for breast cancer.

Association between Nrf1 and TFAM

expression and the clinical prognosis of breast cancer

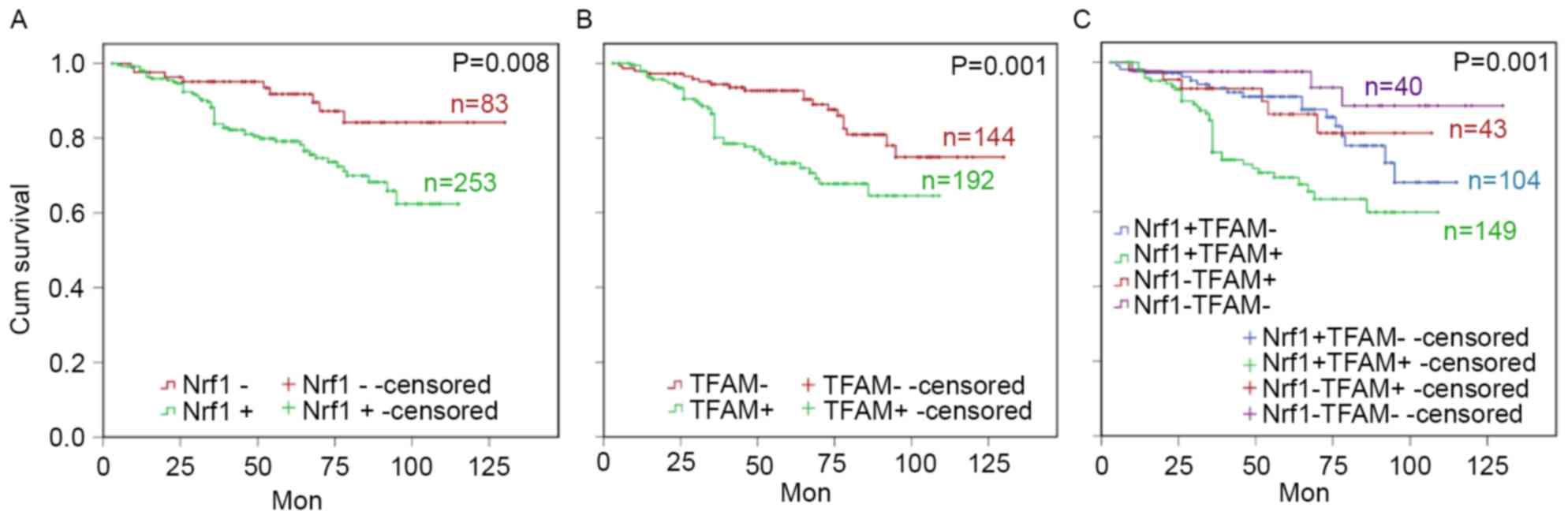

To further evaluate the associations between Nrf1

and TFAM expression and the clinical prognosis of patients with

breast cancer, the relationship between Nrf1 and TFAM expression

and survival time was assessed. Survival analysis revealed that

patients with breast cancer with higher Nrf1 or TFAM expression had

a poorer clinical prognosis, as demonstrated by a shorter survival

time (Fig. 5A and B). At the

predesigned time points, the expected survival time was 91.76

months (95% CI: 86.56–96.96, P=0.008) in patients positive for

Nrf1, which was significantly shorter than in Nrf1-negative

patients (117.55 months; 95% CI: 109.95–125.15). The expected

survival time was 85.56 months (95% CI: 79.78–91.35) in patients

positive for TFAM, which was significantly shorter than in

TFAM-negative patients (113.46 months; 95% CI: 106.88–120.035,

P=0.001). Furthermore, patients positive for Nrf1 and TRAM had the

shortest survival time (82.07 months, 95% CI: 75.154–88.99) and

those negative for both Nrf1 and TRAM had the longest survival time

(121.82 months, 95% CI: 113.01–130.63; P<0.001; Fig. 5C). These results revealed that Nrf1 or

TFAM-positive patients had a shorter survival time, and Nrf1 and

TRAM-double positive patients had a poorer clinical outcome. To

explore whether Nrf1 and TFAM expression was an independent

predictor of survival, univariate and multivariate analyses were

performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. As presented in

Table IV, Nrf1 expression was

independently associated with the prognosis of patients (P=0.034),

together with TFAM (P=0.048), HER2 (P=0.042), PR (P=0.039) and TNM

stages (P=0.028). These results suggest that Nrf1 and TFAM may

serve as predictors for breast cancer prognosis, and the combined

use of Nrf1 and TFAM may assist risk stratification and subsequent

therapy of breast cancer.

| Table IV.Univariate and multivariate analysis

of overall survival the enrolled 336 patients with breast

cancer. |

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of overall survival the enrolled 336 patients with breast

cancer.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 1.119 | 0.926–1.313 | 0.854 |

|

|

|

| Menopausal | 1.959 | 0.793–3.125 | 0.485 |

|

|

|

| Histology

grade | 2.397 | 0.581–4.212 | 0.092 |

|

|

|

| TNM | 6.365 | 3.884–15.845 | 0.005 | 3.645 | 0.968–7.743 | 0.028 |

| HER2 | 3.245 | 1.263–6.235 | 0.012 | 2.026 | 0.668–5.035 | 0.042 |

| ER | 2.826 | 1.035–5.014 | 0.045 | 1.869 | 0.893–3.254 | 0.051 |

| PR | 2.956 | 1.156–5.426 | 0.031 | 1.926 | 0.998–3.547 | 0.039 |

| Nrf1 | 4.896 | 2.552–13.312 | 0.001 | 3.154 | 1.021–7.216 | 0.034 |

| TFAM | 3.936 | 0.031–0.435 | 0.009 | 2.536 | 0.649–5.268 | 0.048 |

Discussion

The mitochondrion is an important organelle in

eukaryotic cells, and is the site where intracellular oxidative

phosphorylation and ATP synthesis occur. Each mitochondrion is

estimated to contain 2–10 copies of mtDNA, which are unique

extranuclear genetic materials that self-replicate and are involved

in transcription and encoding. The synthesis and degradation of

mtDNA is very rapid, independent of the cell cycle, and is

controlled by complex regulatory mechanisms. Furthermore, mtDNA has

poor stability, its synthesis and degradation is susceptible to

exogenous factors, and the mtDNA mutation rate is 10 times greater

than that of nuclear DNA. Mitochondria are also involved in

important cellular activities including cell differentiation,

communication, apoptosis and energy metabolism, but the specific

mechanisms underlying these are still poorly understood (4). An analysis of genome-wide

transcriptional profiling data revealed that ~40 transcripts were

significantly elevated in human breast cancer cells compared with

adjacent stromal tissues, and immunohistochemistry revealed that 15

markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and/or mitochondrial

translation (including Nrf1 and TFAM) were highly expressed in

epithelial breast cancer cells (18).

In estrogen-induced breast carcinogenesis, Nrf1 expression markedly

increased in MCF-10A cells (19).

Furthermore, the mRNA and protein levels of Nrf1 and/or TFAM were

revealed to dramatically increase in different types of breast

cancer (12,13). These results indicate that Nrf1 and

TFAM expression may be associated with the occurrence and

development of breast cancer.

TFAM is encoded by a gene mapped to chromosome10q21

and belongs to the high mobility group box family. Human TFAM may

directly bind to the heavy and light chain promoters to activate

the transcription of mitochondrial genes and regulate mtDNA copies,

which is essential for the functional integrity of mitochondrial

respiratory chain (20–22). TFAM overexpression results in an

increase in mtDNA copies, while TFAM knockout resulted in a

decrease in several murine organs and tissues (22,23). Cells

with TFAM deficiency demonstrated a significant increase in cell

apoptosis (21,24). At the initial stage of p53 dependent

apoptosis, p53 may bind to TFAM to strengthen the binding of TFAM

to DDP-damaged mtDNA, which may contribute to the maintenance and

repair of mtDNA structure and regulate p53-mediated cell apoptosis

(25). Yoshida et al (26) confirmed that TFAM preferentially

recognized DDP-damaged DNA. These results suggest that TFAM may

protect mtDNA against DDP-induced damage and promote repair of the

damaged mtDNA, implying that a high TFAM expression may contribute

to the resistance of cancer cells to DDP-based chemotherapy,

thereby influencing the clinical outcome.

The proximal promoter of the TFAM gene

contains the binding sites of specificity protein 1 (SP1), Nrf1 and

nuclear respiratory factor-2 (Nrf2). Nrf1 binding is a determinant

for the bioactivity of TFAM. Mutation or methylation of the Nrf1

binding site on the TFAM gene may significantly reduce

TFAM transcription, while Nrf1 phosphorylation may stimulate

it. Furthermore, SP1 and Nrf2-induced TFAM transcription

also requires Nrf1 binding (27,28). Thus,

Nrf1 is functionally associated with TFAM and is regarded as

an important regulator of TFAM. Nrf1, together with TFAM,

may regulate the expression of a variety of mitochondrial

functional proteins, including those involved in oxidative

phosphorylation, complex I–V, mtDNA transcription and replication,

protein import and assembly, ion channels, shuttle and translation

(29). Thus, evaluation of Nrf1 and

TFAM expression in breast cancer and adjacent normal tissues, and

their predictive value, will assist in the identification of novel

targets for the individualized therapy of breast cancer, the risk

stratification of breast cancer, and the improvement of clinical

therapeutic efficacy and prognosis of patients with breast

cancer.

In the present study, Nrf1 and TFAM expression was

assessed in breast cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues of

336 patients by immunohistochemistry, and the associations with

clinicopathological features were further evaluated in these

patients. The results of the present study revealed that Nrf1 and

TFAM expression was significantly higher in breast cancer tissue

compared with adjacent normal tissues, suggesting that high

expression of Nrf1 and TFAM may contribute to the high energy

metabolism of breast cancer cells. In estrogen-induced breast

carcinogenesis in MCF-10A cells, Nrf1 expression markedly

increased, further supporting the conclusion that Nrf1 and TFAM are

involved in the tumorigenesis of breast cancer (18). However, further investigation revealed

that the Nrf1-positive rate was higher than the TFAM-positive rate

in breast cancer tissues. This may be explained by the fact that

Nrf1-induced transcription of TFAM is associated with not

only Nrf1 expression levels, but also Nrf1 phosphorylation and

methylation (27,28).

Statistical analysis revealed that high expression

of Nrf1 and TFAM was associated with several clinicopathological

features associated with the prognosis of breast cancer. Patients

with increased Nrf1 or TFAM expression had a shorter survival time,

and survival was shortest in patients positive for Nrf1 and TFAM.

Considering that Nrf1 is able to regulate TFAM expression,

Nrf1 may effectively activate TFAM and its downstream signaling

pathway in patients positive for Nf1 and TFAM. Cancer cells in

these patients may have a more active energy metabolism, increased

proliferation and invasion, and elevated resistance to routine

radiotherapy or chemotherapy, resulting in a poorer clinical

prognosis. The significant associations with HER2, ER, PR

expression status and Nf1 or TFAM expression indicates that HER2,

ER and PR may be involved in the protective mechanism of TFAM

against DDP-mediated mtDNA damage. More mechanistic studies,

however, are required to further clarify the potential associations

between expression of these proteins and their function in the

etiology of breast cancers.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, the

results of the present study are the first to provide clinical

evidence that Nrf1 and/or TFAM expression significantly increase in

breast cancer compared with adjacent normal tissues. In addition,

patients positive for Nrf1 or TFAM have a relatively poor clinical

prognosis, and those positive for Nrf1 and TFAM have the shortest

survival time. These results suggest that Nrf1 and/or TFAM

expression may be useful as a parameter for the determination of

individualized therapy and the prognosis of breast cancer, and Nrf1

and TFAM may be novel targets for the development of targeted

therapies to reduce the resistance of breast cancer cells to

chemotherapeutics.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Natural

Science Foundation of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission

(grant no. 14ZR1408800) and the National Natural Science Foundation

of China (grant no. 81102249).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DDP

|

cisplatin

|

|

TFAM

|

mitochondrial transcription factor

A

|

|

Nrf1

|

nuclear respiratory factor-1

|

|

TMA

|

tissue microarray

|

|

IHC

|

immunohistochemistry

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

ATP

|

adenosine triphosphate

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 65:5–29. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Renatus M, Stennicke HR, Scott FL,

Liddington RC and Salvesen GS: Dimer formation drives the

activation of the cell death protease caspase 9. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 98:pp. 14250–14255. 2001; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Acehan D, Jiang X, Morgan DG, Heuser JE,

Wang X and Akey CW: Three-dimensional structure of the apoptosome:

Implications for assembly, procaspase-9 binding and activation. Mol

Cell. 9:423–432. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mei H, Sun S, Bai Y, Chen Y, Chai R and Li

H: Reduced mtDNA copy number increases the sensitivity of tumor

cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. Cell Death Dis. 6:e17102015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jornayvaz FR and Shulman GI: Regulation of

mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 47:69–84. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

van Tienen FH, Lindsey PJ, van der Kallen

CJ and Smeets HJ: Prolonged Nrf1 overexpression triggers adipocyte

inflammation and insulin resistance. J Cell Biochem. 111:1575–1585.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Benner C, Konovalov S, Mackintosh C, Hutt

KR, Stunnenberg R and Garcia-Bassets I: Decoding a signature-based

model of transcription cofactor recruitment dictated by cardinal

cis-regulatory elements in proximal promoter regions. PLoS Genet.

9:e10039062013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lin CS, Lee HT, Lee SY, Shen YA, Wang LS,

Chen YJ and Wei YH: High mitochondrial DNA copy number and

bioenergetic function are associated with tumor invasion of

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Int J Mol Sci.

13:11228–11246. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Guo J, Zheng L and Liu W, Wang X, Wang Z,

Wang Z, French AJ, Kang D, Chen L, Thibodeau SN and Liu W: Frequent

truncating mutation of TFAM induces mitochondrial DNA depletion and

apoptotic resistance in microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer.

Cancer Res. 71:2978–2987. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Vadrot N, Ghanem S, Braut F, Gavrilescu L,

Pilard N, Mansouri A, Moreau R and Reyl-Desmars F: Mitochondrial

DNA maintenance is regulated in human hepatoma cells by glycogen

synthase kinase 3β and p53 in response to tumor necrosis factor α.

PLoS One. 7:e408792012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mo M, Peng F, Wang L, Peng L, Lan G and Yu

S: Roles of mitochondrial transcription factor A and

microRNA-590-3p in the development of bladder cancer. Oncol Lett.

6:617–623. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yao J, Zhou E, Wang Y, Xu F, Zhang D and

Zhong D: microRNA-200a inhibits cell proliferation by targeting

mitochondrial transcription factor A in breast cancer. DNA Cell

Biol. 33:291–300. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fuchinoue F, Hirotani Y, Nakanishi Y,

Yamaguchi H, Nishimaki H, Noda H, Tang XY, Iizuka M, Amano S,

Sugitani M, et al: Overexpression of PGC1α and accumulation of p62

in apocrine carcinoma of the breast. Pathol Int. 65:19–26. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Blair SL,

Burstein HJ, Cyr A, Elias AD, Farrar WB, Forero A, Giordano SH and

Goldstein LJ: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast

Cancer, Version 3.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 12:542–590. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hu J, Wang N and Wang YJ: XRCC3 and RAD51

expression are associated with clinical factors in breast cancer.

PLoS One. 8:e721042013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M,

McShane LM, Allison KH, Allred DC, Bartlett JM, Bilous M,

Fitzgibbons P, et al: Recommendations for human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of

Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical

practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 31:3997–4013. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, Bassett

LW, Berry D, Bland KI, Borgen PI, Clark G, Edge SB, Hayes DF, et

al: Revision of the American Joint Committee on cancer staging

system for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 20:3628–3636. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D,

Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Salem AF, Tsirigos A, Lamb R, Sneddon S,

Hulit J, Howell A and Lisanti MP: Mitochondria ‘fuel’ breast cancer

metabolism: Fifteen markers of mitochondrial biogenesis label

epithelial cancer cells, but are excluded from adjacent stromal

cells. Cell Cycle. 11:4390–4401. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chatterjee A, Ronghe A, Singh B, Bhat NK,

Chen J and Bhat HK: Natural antioxidants exhibit chemopreventive

characteristics through the regulation of CNC b-Zip transcription

factors in estrogen-induced breast carcinogenesis. J Biochem Mol

Toxicol. 28:529–538. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kang D, Kim SH and Hamasaki N:

Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM): Roles in maintenance

of mtDNA and cellular functions. Mitochondrion. 7:39–44. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Larsson NG, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, Oldfors

A, Rustin P, Lewandoski M, Barsh GS and Clayton DA: Mitochondrial

transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and

embryogenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 18:231–236. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ekstrand MI, Falkenberg M, Rantanen A,

Park CB, Gaspari M, Hultenby K, Rustin P, Gustafsson CM and Larsson

NG: Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy

number in mammals. Hum Mol Genet. 13:935–944. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pohjoismäki JL, Wanrooij S, Hyvärinen AK,

Goffart S, Holt IJ, Spelbrink JN and Jacobs HT: Alterations to the

expression level of mitochondrial transcription factor A TFAM,

modify the mode of mitochondrial DNA replication in cultured human

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:5815–5828. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang J, Silva JP, Gustafsson CM, Rustin P

and Larsson NG: Increased in vivo apoptosis in cells lacking

mitochondrial DNA gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:pp.

4038–4043. 2001; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Choi YS, Kim S and Pak YK: Mitochondrial

transcription factor A (mtTFA) and diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin

Pract. 54 Suppl 2:S3–S9. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yoshida Y, Izumi H, Torigoe T, Ishiguchi

H, Itoh H, Kang D and Kohno K: P53 physically interacts with

mitochondrial transcription factor A and differentially regulates

binding to damaged DNA. Cancer Res. 63:3729–3734. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Piantadosi CA and Suliman HB:

Mitochondrial transcription factor A induction by redox activation

of nuclear respiratory factor 1. J Biol Chem. 281:324–333. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Choi YS, Kim S, Kyu Lee H, Lee KU and Pak

YK: In vitro methylation of nuclear respiratory factor-1 binding

site suppresses the promoter activity of mitochondrial

transcription factor A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 314:118–122.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kelly DP and Scarpulla RC: Transcriptional

regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and

function. Genes Dev. 18:357–368. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|