Introduction

In 1882, Halsted pioneered the radical resection of

the breast. Breast surgery methods have changed since and

clinicians commonly perform breast-conserving surgery. However, the

optimal approach for radical resection remains controversial

(1). Along with social progress and

improvements in the quality of life, patients with cancer,

particularly patients with breast cancer have increasing

requirements for the function and cosmetic outcome following

surgery (2,3). A previous study identified that 61% of

patients reported that the opinions of their partners of the scars

were important to them (4). The way

an incision is closed and managed post-operatively affects cosmetic

outcome (5). Historically, in breast

cancer surgery, simultaneously ensuring treatment effect, shrinking

excision scope and attending to the cosmetic effect has been

important (6). To improve the

aesthetic results for female patients undergoing breast cancer

surgery, surgical techniques have been developed to render scars

less noticeable (7,8).

In China, the majority of patients with breast

cancer are treated with modified radical surgery using

discontinuous silk suture, which leaves a very noticeable scar

(9). A study on cosmetic surgery

identified that 50% of patients reported that the extent of the

visual scar greatly affected their self-assessment of the outcome

(10).

Previous studies have assessed how drugs can be used

to decrease scarring but the results demonstrated that there

remains no ‘gold standard’ for the prevention and treatment of

hypertrophic scars (11,12). The authors of the present study

evaluated the methods of closing wounds in modified radical surgery

in April 2014 and proposed using intradermal suture with Ti-Ni

memory alloy wire (13). After >2

years of practice and observation, the wounds of patients with

scarring markedly improved following intradermal suture with Ti-Ni

memory alloy wire.

The primary objective of the present study is to

assess the impact of using a Ti-Ni memory alloy wire intradermal

sutures on the cosmetic outcome of the wound scar within 25 weeks

following mastectomy.

Materials and methods

Study design

Prior to the start of the present study, the methods

of surgical suturing were altered and the postoperative effects

were observed. After >2 years of observing and evaluating

Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) scores and the number of wound healing

day(s), the present study reviewed the retrospective data. The

present study is a retrospective observational cohort study with

parallel groups and compares conventional closure with closure

using intradermal sutures and Ti-Ni memory alloy wire in patients

undergoing mastectomy with or without axillary surgery.

Setting

The present study included diagnostic surgery and

post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with breast

cancer in the Department of Thoracic Surgery and Oncology of the

First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University (Shaanxi,

China), a process that took ~6 months. The patients were treated

with interrupted suture or intradermal suture.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Female

patients with operable breast cancer (invasive carcinoma and/or

ductal carcinoma in situ); ii) age, ≥18 and ≤85 years; iii)

scheduled for mastectomy either alone or in association with

axillary clearance; iv) either sentinel lymph node biopsy or

standard level I/II axillary node dissection (14); v) written hospital-approved informed

consent by the patient; and vi) surgical wound classified class I

(Surgical Wound Classification) (15). Patients were excluded if any of the

following criteria were met: i) Undergoing surgery for modified

radical mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction, cosmetic

breast operations, reduction, expansion, insertion of a prosthesis,

duct ectasia, infective breast disease or implant; ii) surgical

wounds identified as class II, III or IV using Centers for Disease

Control surgical site infection Surgical Wound Classification

(15); iii) inflammatory breast

cancer or skin ulceration; iv) presence of physical or psychiatric

conditions that could impair outcome assessment and intended

follow-up (5); v) personal or family

skin scar history; vi) received an experimental drug or used an

experimental medical device within 30 days prior to the planned

start of treatment; vii) employees of the assessor associated with

the proposed study or other studies under the direction of that

assessor; and viii) unlikely to comply with chemotherapy or

complete the 25-week follow-up visit.

Patients

The first patient received intradermal sutures using

Ti-Ni memory alloy wire in April 2014. In total, 98 female patients

aged between 24 and 74 years, categorized into the active (n=50)

and control (n=48) groups, were enrolled between April 2014 and

April 2016. A total of 10 patients suffered from diabetes in the

active group and 9 patients suffered from diabetes in the control

group. The patients of control group were treated with traditional

methods of wound closure. The present study reviewed all patient

data for those admitted to the Second Department of Thoracic

Surgery of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong

University (Shaanxi, China) who met the inclusion criteria. The

present study focused on scarring. Baseline data were collected

following enrollment during the therapy period. The First

Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University Ethics Committee

approved the present study. Written informed consent was obtained

from all patients.

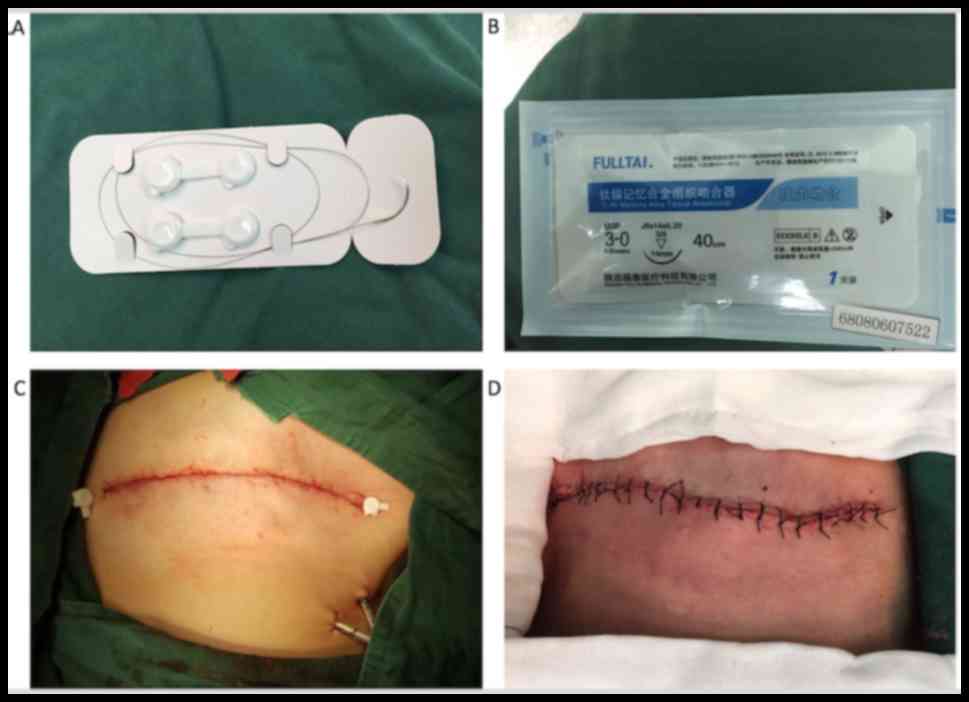

Study interventions

Experienced breast surgeons using a standardized

technique performed mastectomies (16). The skin incision included the tumor

biopsy site, any invaded or edematous skin and the nipple-areola

complex (17). The present study

addressed the type of wound closure in mastectomy. The patients

were divided into two groups, and the two groups were distinguished

by the use of two different types of wound closure. In the

intradermal suture group, intradermal suture using Ti-Ni memory

alloy wire was implemented. In the conventional closure group, the

incision was closed using the interrupted transcutaneous pattern

with Chinese silk (Fig. 1). These two

sutures were removed when the wounds were adequately healed (i.e.,

re-establishment of normal tissue integrity).

All patients were provided with a drainage tube and

suction bottle to prevent subcutaneous seroma following mastectomy.

All patients received chemotherapy and the same follow-up plan,

including chest-abdominal computed tomography and tumor markers,

was implemented every 3 months (18,19). The

scars were assessed 25 weeks following mastectomy. All scars were

assessed independently by three observers (one oncologist and two

breast cancer research associates) on the same day, using the VSS.

The VSS observes four physical characteristics of scars:

Vascularity, pigmentation, pliability and height (20,21). Each

variable contains ranked subscales that may be summed to obtain a

total score ranging from 0 to 13, with 0 representing normal skin

(Table I) (20,21).

| Table I.Vancouver Scar Scale for assessment of

the physical characteristics of scars. |

Table I.

Vancouver Scar Scale for assessment of

the physical characteristics of scars.

| Characteristic | Score |

|---|

| Vascularity |

|

|

Normal | 0 |

| Pink | 1 |

| Red | 2 |

|

Purple | 3 |

| Pigmentation |

|

|

Normal | 0 |

|

Hypopigmentation | 1 |

|

Hyperpigmentation | 2 |

| Pliability |

|

|

Normal | 0 |

| Supple

(flexible with minimal resistance) | 1 |

| Yielding

(gives way to pressure) | 2 |

| Firm

(inflexible not easily moved; resistant to manual pressure) | 3 |

| Ropes

(rope-like tissue that blanches with extension of scar) | 4 |

|

Contracture (permanent

shortening of scar leading to deformity or distortion) | 5 |

| Height, mm |

|

| Normal

(flat) | 0 |

|

<2 | 1 |

| 2–5 | 2 |

|

>5 | 3 |

| Total score | 13 |

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

computer software SPSS (version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA). In the present study, the differences between the baseline

characteristics of patients were compared using Fisher's exact test

for the different categories and independent sample t-test for

continuous variables. The endpoint means of the VSS scores were

analyzed using independent sample t-test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of enrolled

patients

All patients completed the present study. The

baseline characteristics of the patients were provided (Table II). The present study compared the

baseline characteristics of the two groups. The groups were similar

in terms of mean age (P>0.05), body mass index (P>0.05),

operating time (P>0.05), blood loss (P>0.05), length of

post-operative hospital stay (P>0.05), pathological stage (7th

edition; American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International

Cancer Control tumor-node-metastasis staging systems; P>0.05)

and medical history (P>0.05) (22).

| Table II.Comparison of the baseline

characteristics of patients who underwent mastectomy (n=98). |

Table II.

Comparison of the baseline

characteristics of patients who underwent mastectomy (n=98).

| Characteristics | Active group

(n=50) | Control group

(n=48) | χ2 or

t-value | P-value |

|---|

| Mean ± SD age,

years | 47.38±11.64 | 46.58±11.79 | 0.337

(t-value) | 0.737 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 26.55±4.38 | 27.17±4.21 | 0.710

(t-value) | 0.479 |

| Diabetes, n

(%) | 0 | 1 (2.08) | | 0.490 |

| Pulmonary history

(COPD), n (%) | 1 (2.00) | 0 | | 1.000 |

| Cardiac history

(coronary disease), n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.08) | | 0.490 |

| Smoking history, n

(%) | 2 (4.00) | 2 (4.17) | | 0.676 |

| Working outside the

home, n (%) | 6

(12.00) | 4 (8.33) | | 0.741 |

| Pathological stage,

n (%) | | | 1.344

(χ2-value) | 0.969 |

| I | 1 (2.00) | 1 (2.08) |

|

|

|

IIA | 12 (24.00) | 12 (25.00) |

|

|

|

IIB | 15 (30.00) | 17 (35.42) |

|

|

|

IIIA | 9

(18.00) | 8

(16.67) |

|

|

|

IIIB | 11 (22.00) | 9

(18.75) |

|

|

|

IIIC | 1 (2.00) | 1 (2.08) |

|

|

| IV | 1 (2.00) | 0 |

|

|

| Mean ± SD operating

time, min | 100.98±11.31 | 103.54±11.01 | 1.135

(t-value) | 0.259 |

| Mean ± SD blood

loss, ml | 52.30±17.58 | 50.08±15.82 | 0.655

(t-value) | 0.514 |

| Mean ± SD

postoperative hospital stay, days | 4.36±0.83 | 4.45±0.97 | 0.542

(t-value) | 0.589 |

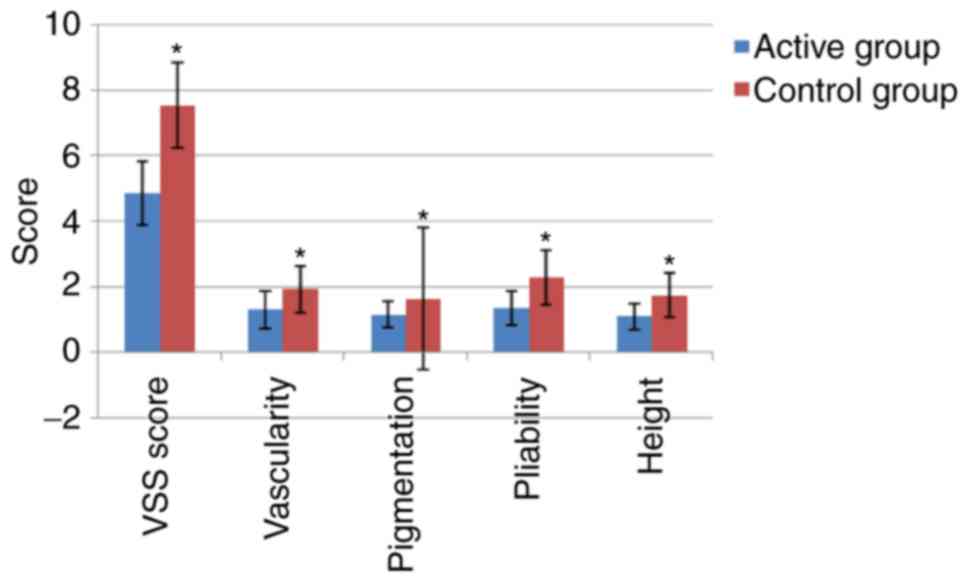

Cosmetic outcome

Results demonstrated that the mean VSS score of the

active group was decreased (indicating improved cosmetic outcome)

compared with that of the control group (P<0.001; Table III). The four features of the VSS

scores differed statistically (P<0.001). The cosmetic results of

suturing for four cases are also presented in Fig. 2. A comparison of cosmetic results

between the experimental and control groups is shown in Fig. 3, and statistical differences between

the active and control groups are shown.

| Table III.Vancouver Scar Scale scores for the

active and the control group. |

Table III.

Vancouver Scar Scale scores for the

active and the control group.

|

Outcomea | Active group

(n=50) | Control group

(n=48) | t-value | P-value |

|---|

| Vancouver Scar

Scale score | 4.86±0.97 | 7.54±1.30 | 11.518 | <0.001 |

|

Vascularity | 1.30±0.58 | 1.92±0.71 | 4.718 | <0.001 |

|

Pigmentation | 1.14±0.40 | 1.63±2.16 | 5.336 | <0.001 |

|

Pliability | 1.34±0.52 | 2.27±0.84 | 6.543 | <0.001 |

|

Height | 1.08±0.40 | 1.73±0.68 | 5.771 | <0.001 |

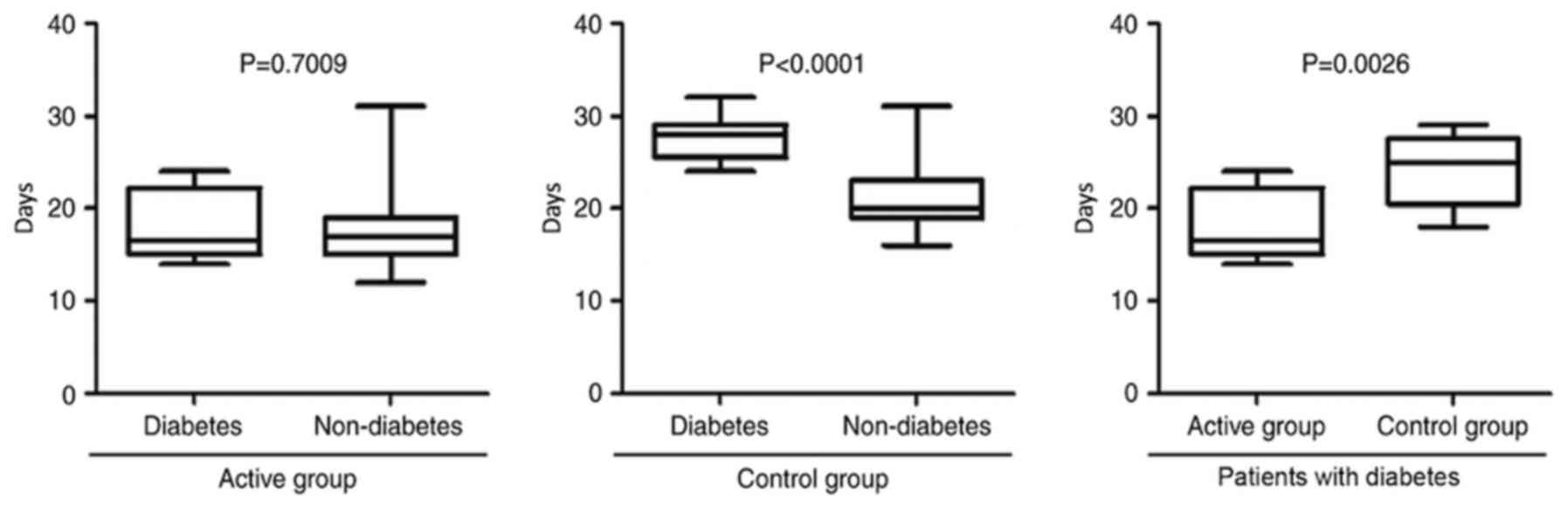

Unexpected benefits of using memory

alloy wire in patients with diabetes

Aside from improved recovery from the surgical

wound, the present study also observed accelerated wound healing in

both groups. The mean number of wound healing days required to take

out stitches was decreased for the active group compared with that

for the control group in patients with diabetes (P=0.0026; Fig. 4). Results indicated that using Ti-Ni

memory alloy wire was able to decrease the days of wound healing

required between patients with diabetes and their non-diabetic

counterparts (P=0.7009; Fig. 4).

Results of the present study suggested that using memory alloy

facilitated wound healing.

Discussion

In the present study, the scar of patients in the

active group was limited to a light spot in the majority of cases.

The results of the present study indicated that patients whose

incisions were closed using intradermal suture with Ti-Ni memory

alloy wire suture exhibited an improved cosmetic outcome compared

with those for whom incisions were closed using the interrupted

suturing technique. The cosmetic outcome was assessed using VSS.

VSS is a reliable, comprehensive approach for assessing linear

surgical scars (23). VSS assesses

four subjective variables (vascularity, pigmentation, pliability

and height) within a range of 0–13 for the total score (calculated

as the sum of all four subjective variables scores), where a lower

score (0–4) indicates improved healing (21).

In China, certain surgeons use discontinuous silk

suture to close the skin incision (9,24).

Therefore, suture track scars are present on each side of the

incision in numerous cases and one can observe a suture reaction,

inflammation, liquefaction, infection or incision dehiscence

requiring secondary suture (4). Scars

are usually caused by excessive repair of skin wounds due to

excessive proliferation, activation and migration of fibroblasts.

Increase in the biosynthesis of fibroblasts cause excessive

collagen deposition of extracellular matrix (25,26).

Collagen fibers also form here as a result of the body synthesizing

collagen at an increased rate compared with that at which it

catabolizes collagen over a longer period of time (27,28).

The present study indicated that continuous

intradermal suture was able to decrease scar formation compared

with the control group, although patients exhibited scar

hyperplasia. Despite this, intradermal suture may decrease the

discomfort the hyperplastic scar causes, including prominent

surface, thick texture, local pain, heat-induced itch. Intradermal

suture may also improve the function of sleep quality (29–31).

Typically, the time taken for wounds to heal in patients without

diabetes is decreased compared with patients with diabetes

(32–35). Consistent with these previous studies,

it was indicated in the present study that the time taken for

wounds to heal in patients with diabetes was increased compared

with that of the patients without diabetes in the control group.

However, the time taken for wounds to heal in patients with and

without diabetes was similar in the active group. Furthermore, it

was indicated that the time taken for wounds to heal in patients

with diabetes differed significantly between the active and control

groups, the healing time of active groups was shorter compared with

that of control groups. The present study suggested that continuous

intradermal suture of incision with Ti-Ni memory alloy wire may

promote skin incisions to heal and decrease scar hyperplasia, and

therefore this method may be recommended to other surgeons for

patients undergoing mastectomy with or without axillary

surgery.

The present study was a retrospective, observational

cohort study and had a number of limitations. The present study was

not double blind, which may have generated bias. The 2-year

follow-up period was short, and the prognosis of disease was not

assessed. VSS reflects the different physical characteristics

carried out by the observer, reflecting different physiological

aspects of wound healing and scar maturation. The present study

identified that VSS scores objectively reflected scar maturation.

However, the VSS does not include a self-assessment of the patient

outcome.

To conclude, the intradermal suture technique offers

an improved cosmetic outcome for patients undergoing mastectomy

with or without axillary surgery. The present study suggested that

intradermal suture using Ti-Ni memory alloy wire may represent an

effective means of inhibiting scars from forming following

mastectomy. For patients undergoing intradermal suture using Ti-Ni

memory alloy wire, the scar was less noticeable and wound healing

was improved compared with the control group, particularly in

patients with diabetes.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National

Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (grant nos.

81402506 and 81602597).

References

|

1

|

Akram M and Siddiqui SA: Breast cancer

management: Past, present and evolving. Indian J Cancer.

49:277–282. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sehl M, Lu X, Silliman R and Ganz PA:

Decline in physical functioning in first 2 years after breast

cancer diagnosis predicts 10-year survival in older women. J Cancer

Surviv. 7:20–31. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Derks MG, de Glas NA, Bastiaannet E, de

Craen AJ, Portielje JE, van de Velde CJ, van Leeuwen FE and Liefers

GJ: Physical functioning in older patients with breast cancer: A

prospective cohort study in the TEAM trial. Oncologist. 7:946–953.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Joyce CW, Murphy S, Murphy S, Kelly JL and

Morrison CM: Scar wars: Preferences in breast surgery. Arch Plast

Surg. 42:596–600. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang ZT, Zhang HW, Fang XD, Wang LM, Li

XX, Li YF, Sun XW, Carver J, Simpkins D, Shen J and Weisberg M:

Cosmetic outcome and surgical site infection rates of antibacterial

absorbable (Polyglactin 910) suture compared to Chinese silk suture

in breast cancer surgery: A randomized pilot research. Chin Med J

(Engl). 124:719–724. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ünsal MG, Dural AC, Çelik MF, Akarsu C,

Başoğlu İ, Dilege ME, Kapan S and Alış H: The adaptation process of

a teaching and research hospital to changing trends in modern

breast surgery. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 31:34–38. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Peyser PM, Abel JA, Straker VF, Hall VL

and Rainsbury RM: Ultraconservative skin-sparing ‘keyhole’

mastectomy and immediate breast and areola reconstruction. Ann R

Coll Surg Engl. 82:227–235. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shrotria S: The periareolar incision -

gateway to the breast! Eur J Surg Oncol. 27:601–603. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang J, Zhang YF, Wang X, Wang J, Yang X,

Gao YQ and Fang Y: Treatment outcomes of occult breast carcinoma

and prognostic analyses. Chin Med J (Engl). 126:3026–3029.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hoeller U, Kuhlmey A, Bajrovic A, Grader

K, Berger J, Tribius S, Fehlauer F and Alberti W: Cosmesis from the

patient's and the doctor's view. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

57:3452003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

O'Kane S: Wound remodeling and scarring. J

Wound Care. 11:296–299. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Truong PT, Lee JC, Soer B, Gaul CA and

Olivotto IA: Reliability and validity testing of the patient and

observer scar assessment scale in evaluating linear scars after

breast cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 119:487–494. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Neelakantan L, Zglinski JK, Frotscher M

and Eggeler G: Design and fabrication of a bending rotation fatigue

test rig for in situ electrochemical analysis during fatigue

testing of NiTi shape memory alloy wires. Rev Sci Instrum.

84:0351022013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kinoshita T, Takasugi M, Iwamoto E,

Akashi-Tanaka S, Fukutomi T and Terui S: Sentinel lymph node biopsy

examination for breast cancer patients with clinically negative

axillary lymph nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Surg.

191:225–229. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yamamoto T, Takahashi S, Ichihara K,

Hiyama Y, Uehara T, Hashimoto J, Hirobe M and Masumori N: How do we

understand the disagreement in the frequency of surgical site

infection between the CDC and Clavien-Dindo classifications? J

Infect Chemother. 21:130–133. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li YJ, Huang XE and Zhou XD: Local breast

cancer recurrence after mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery

for Paget's disease: A meta-analysis. Breast Care (Basel).

9:431–434. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ouldamer L, Bonastre J, Brunet-Houdard S,

Body G, Giraudeau B and Caille A: Dead space closure with quilting

suture versus conventional closure with drainage for the prevention

of seroma after mastectomy for breast cancer (QUISERMAS): Protocol

for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open.

6:e0099032016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

MacFater H, MacFater W, Hill A and Lill M:

Individualised follow-up booklets improve recall and satisfaction

for cancer patients. N Z Med J. 130:39–45. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Allinson VM and Dent J: Supportive care

after breast cancer surgery. Nurs Times. 110:20–23. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pauline T, Truong F, Yong CM, Hayashi A,

Runkel JA, Phillips T and Olivotto IA: Standardized assessment of

breast cancer surgical scars integrating the vancouver scar scale,

short-form mcgill pain questionnaire and patients' perspectives.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 116:1291–1299. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nedelec B, Shankowsky HA and Tredget EE:

Rating the resolving hypertrophic scar: Comparison of the vancouver

scar scale and scar volume. J Burn Care Rehabil. 21:205–212. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ursaru M, Jari I, Popescu R, Negru D, Naum

A and Scripcariu V: Multifactorial analysis of local and lymph node

recurrences after conservative or radical surgery for stage 0–II

breast cancer. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 118:1062–1067.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kaartinen IS, Välisuo PO, Bochko V,

Alander JT and Kuokkanen HO: How to assess scar hypertrophy - a

comparison of subjective scales and Spectrocutometry: A new

objective method. Wound Repair Regen. 19:316–323. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhao WX, Wang B, Yan SY and Zhang LY:

Strategy of points, lines and layers in needle assisted laparoscope

functional modified neck dissection through bilateral breast

approach. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 54:823–827. 2016.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liebl H and Kloth LC: Skin cell

proliferation stimulated by microneedles. J Am Coll Clin Wound

Spec. 4:2–6. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guo J, Lin Q, Shao Y, Rong L and Zhang D:

miR-29b promotes skin wound healing and reduces excessive scar

formation by inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad/CTGF signaling pathway.

Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 95:437–442. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li J, Chen L, Cao C, Yan H, Zhou B, Gao Y,

Li Q and Li J: The long non-coding RNA LncRNA8975-1 is upregulated

in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts and controls collagen expression.

Cell Physiol Biochem. 40:326–334. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li H, Yang L, Zhang Y and Gao Z:

Kaempferol inhibits fibroblast collagen synthesis, proliferation

and activation in hypertrophic scar via targeting TGF-β receptor

type I. Biomed Pharmacother. 83:967–974. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kotaluoto S, Pauniaho SL, Helminen M,

Kuokkanen H and Rantanen T: Wound healing after open appendectomies

in adult patients: A prospective, randomised trial comparing two

methods of wound closure. World J Surg. 36:2305–2310. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Koskela A, Kotaluoto S, Kaartinen I,

Pauniaho SL, Rantanen T and Kuokkanen H: Continuous absorbable

intradermal sutures yield better cosmetic results than

nonabsorbable interrupted sutures in open appendectomy wounds: A

prospective, randomized trial. World J Surg. 38:1044–1050. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Paolini S, Morace R, Lanzino G, Missori P,

Nano G, Cantore G and Esposito V: Absorbable intradermal closure of

elective craniotomy wounds. Neurosurgery. 62 Suppl 2:ONS490–ONS492.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sorg H, Tilkorn DJ, Hager S, Hauser J and

Mirastschijski U: Skin wound healing: An update on the current

knowledge and concepts. Eur Surg Res. 58:81–94. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Nouvong A, Ambrus AM, Zhang ER, Hultman L

and Coller HA: Reactive oxygen species and bacterial biofilms in

diabetic wound healing. Physiol Genomics. 48:889–896. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Reed GW, Salehi N, Giglou PR, Kafa R,

Malik U, Maier M and Shishehbor MH: Time to wound healing and major

adverse limb events in patients with critical limb ischemia treated

with endovascular revascularization. Ann Vasc Surg. 36:190–198.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Khamaisi M, Katagiri S, Keenan H, Park K,

Maeda Y, Li Q, Qi W, Thomou T, Eschuk D, Tellechea A, et al: PKCδ

inhibition normalizes the wound-healing capacity of diabetic human

fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 126:837–853. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|