Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the 6th most

common type of primary malignant neoplasm and the third leading

cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide. The morbidity and

mortality rates of the disease increase annually (1–3). HCC forms

heterogeneous tumors and its development is driven by numerous

factors. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and

HBV-associated cirrhosis account for the majority of cases of HCC,

which constitutes 70–90% of liver cancer cases according to

histological examination (4). The

efficacies of existing key HCC therapies, including hepatectomy,

percutaneous ethanol injection, radio frequency ablation and liver

transplantation, have improved in recent years. However, the

disease often progresses or recurs despite appropriate treatment

regimes, and the overall survival (OS) of HCC patients remains poor

(5). Therefore, novel molecular

markers that contribute to the development of effective treatment

strategies and the improved prognosis of patients with HCC are

urgently required.

FXYD domain-containing ion transport regulator 3

(FXYD3), also known as mammary tumor 8, belongs to the FXYD protein

family and is localized in the cell membrane and cytoplasm. It has

been reported that FXYD3 acts as a regulator of sodium-potassium

(Na+-K+) ATPase (6,7). One study

demonstrated that this integral cell membrane protein was

differentially expressed between tumor cells and normal cells,

regulated cell proliferation, cell apoptosis and tumor metastasis,

influenced the cell cycle, and participated in tumor angiogenesis

and progression (8). However, the

association between the expression of FXYD3 and tumor occurrence

and development remains poorly understood. FXYD3 is expressed in

numerous healthy tissues, including the uterus, stomach, colon and

skin (9,10). However, FXYD3 expression has also been

identified in various types of cancer, including breast cancer

(7), prostate cancer (11,12),

colorectal cancer (CRC) (13),

pancreatic cancer (14–16), esophageal squamous carcinoma (ESCC)

(17), lung cancer (18,19) and

glioma (20). Furthermore, FXYD3 was

demonstrated to be associated with the clinical prognoses of these

types of cancer. To the best of our knowledge, the association

between FXYD3 expression and HCC prognosis has not been previously

evaluated. In the present study, the expression of FXYD3 in HCC

tissues was investigated using reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), western blotting and

immunohistochemical (IHC) staining analyses to determine the

prognostic value of FXYD3 for patients with HCC.

Materials and methods

Study population

The present study was approved by the Research

Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center

(Guangzhou, China). All patients provided informed consent for

study participation prior to undergoing tumor resection. Tissue

samples were obtained from 217 patients diagnosed with HCC who had

undergone curative resection at the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer

Center between August 2002 and November 2011. Among them, 193 were

males and 24 were females, with age ranging from 20–75 years

(median, 49 years). A total of 137 paraffin-embedded primary HCC

tumor samples were selected (collected between January 2002 and

June 2008). Furthermore, 80 pairs of HCC tissues and adjacent

non-cancerous liver tissues were also selected from the Sun Yat-sen

University Cancer Center specimen repository (originally collected

between January 2009 and November 2011). A total of 6

paraffin-embedded breast cancer tissue samples from the Sun Yat-sen

University Cancer Center specimen repository were also used in the

present study as a positive control.

The following inclusion criteria were applied to the

present study: Histologically verified primary HCC, no previous

adjuvant chemotherapy, no diagnosis of distant metastases prior to

surgery and access to complete follow-up data. Patient tissues were

excluded from the study when there was evidence of Child-Pugh class

B or C liver disease. Postoperative follow-up included regular

recurrence and metastasis surveillance testing by measuring patient

serum α-fetoprotein levels, abdominal ultrasonography, chest

radiography, computed tomography, hepatic angiography and biopsies

at 2–4-month intervals. Patients with confirmed disease recurrence

received further treatment, including a second surgical resection.

The median follow-up time was 43.9 months (range, 1–131 months). A

total of 99 mortalities occurred during the follow-up period

(45.6%) and 118 patients (54.4%) survived. OS was defined as the

time from the date of surgery to the date of mortality from any

cause, including HCC. Disease-free survival was defined as the time

from the date of surgery to the date of regional relapse or distant

metastasis, and was determined among the remaining patients on the

date of their last follow-up appointment.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from 80 pairs of HCC tissues

and matched non-cancerous liver tissues, using TRIzol solution

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations

were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA with an absorbance ratio from 1.8 to

2.0 at 260 and 280 nm was considered as pure. Each cDNA sequence

was synthesized from 2 µg total RNA using a RevertAid First Strand

cDNA Synthesis kit (Toyobo Life Science, Osaka, Japan). The

resulting cDNA was processed by RT-qPCR to determine the relative

FXYD3 mRNA expression levels. GAPDH served as an internal control.

RT-qPCR was performed in triplicate at a final volume of 10 µl,

consisting of 5 µl 2X SYBR Green master mix (Toyobo Life Science),

0.4 µl 20 mmol/l forward primer, 0.4 µl reverse primer, 0.75 µl

sample cDNA and 3.45 µl RNase-free water. The reaction mixture was

preheated to 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 30

sec and 60°C for 60 sec. The following primers were used for

RT-qPCR: FXYD3 forward, 5′-GGACGCCAATGACCTAGAAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGGTGATGAGAGGTGGAGTC-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3′. The data were analyzed using the

quantification cycle (2−ΔΔCq) method (21) and the results were averaged and

expressed in relative expression units after normalization.

Protein extraction and western

blotting

Western blotting was performed to analyze the FXYD3

protein expression levels in the clinical specimens from patients

with HCC and the matched control tissues. Total protein was

extracted from the fresh-frozen tissue samples using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute for

Biotechnology, Haimen, China) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Protein concentrations were determined using a

Bicinchoninic Acid medProtein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). A total of 30 µg protein per sample was separated by 12%

SDS-PAGE and electro-transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride

membranes (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The

membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered

saline-Tween for 60 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the

membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with a rabbit anti-FXYD3

monoclonal antibody (cat. no. ab205534; dilution 1:1,000; Abcam,

Cambridge, UK) (22) and GAPDH (cat.

no. 10494-1-AP; dilution 1:5,000; ProteinTech Group, Inc., Chicago,

IL, USA). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with

appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG

(cat. no. 7074; dilution 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.,

Danvers, MA, USA) for 60 min at room temperature. The membranes

were washed with TBS with 20% Tween-3 times and peroxidase activity

was detected on X-ray films using an enhanced chemiluminescence

detection system (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The band

intensities were measured by densitometry using Quantity One

software v4.6.9 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

The size of the FXYD3 band was consistent with the predicted

molecular weight of the FXYD3 protein and was normalized to GAPDH

protein levels.

IHC

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections, 4-µm thick, were

cut and mounted on glass slides. The samples were subsequently

deparaffinized in dimethylbenzene and rehydrated using 100, 95, 90,

80 and 70% ethanol solutions. Endogenous peroxidase activity was

blocked using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature for 10

min. For antigen retrieval, the slides were boiled in

citrate-hydrochloric acid (pH 6.0) (cat. no. ZLI-9065; OriGene

Technologies, Inc.) for 20 min in a pressure cooker. Subsequent to

washing in PBS, the slides were treated with 5% sheep serum albumin

(cat. no. ab7481; Abcam) at room temperature for 15 min to prevent

non-specific binding. The tissue sections were then incubated with

rabbit anti-FXYD3 (cat. no. ab205534; dilution 1:400; Abcam)

overnight at 4°C. Following the primary antibody incubation, the

tissue sections were incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary

antibody (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA)

for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were then incubated with

3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride for 10 min at room

temperature, all sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for

~2 min at room temperature. For the negative control, the primary

antibody was replaced with rabbit IgG (cat. no. 3900; dilution

1:400; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) (data not shown). A

positive control was provided by breast cancer tissue samples. The

semi-quantitative FXYD3 expression score was calculated as the sum

of the score for the proportion of positively stained tumor cells

and the score for staining intensity. These scores were determined

by two pathologists blinded to the clinical characteristics of the

patients. The proportions of positively stained tumor cells were

scored as follows: 0, <5% (negative); 1, 5–25% (sporadic); 2,

25–50% (focal); and 3, >50% (diffuse). Staining intensity was

graded according to the following scale: 0, no staining; 1, weak

staining (light yellow); 2, moderate staining (yellow-brown); and

3, strong staining (brown). The total immunostaining score was

calculated by multiplying the proportion of positively stained

cells by the staining intensity score, yielding a value ranging

from 0–9.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0

software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Scatterplots and bar graphs

were created using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software,

Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The distributions of the baseline

characteristics of the two groups, which were separated according

to a cutoff FXYD3 level of 1.285, were compared using χ2

or Fisher's exact tests. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test

were used to plot survival curves and to calculate the difference

in survival between the groups. Parameters found to be significant

by univariate analysis were further evaluated by multivariate Cox

regression analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Patients and clinicopathological

data

The expression of FXYD3 was analyzed in each tissue

sample at the mRNA and protein levels. FXYD3 expression in the 80

pairs of HCC tissues and matched non-cancerous liver tissues was

analyzed by RT-qPCR, and 24 pairs were also evaluated by western

blotting. Furthermore, 137 paraffin-embedded primary HCC tumor

samples were analyzed by IHC analysis. The associations between

patient clinicopathological data and FXYD3 expression levels in

patients with HCC are summarized in Table

I. χ2 tests demonstrated that FXYD3 expression

levels were significantly different between patients with one vs.

multiple tumors (P=0.011).

| Table I.Clinicopathological data of patients

with hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological data of patients

with hepatocellular carcinoma.

|

|

| FXYD3 protein

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | Cases, n | Low, n (%) | High, n (%) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

≤50 | 70 | 43 (61.4) | 27 (38.6) | 0.231 |

|

>50 | 67 | 34 (50.7) | 33 (49.3) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 124 | 69 (55.6) | 55 (44.4) | 0.775 |

|

Female | 13 | 8

(61.5) | 5

(38.5) |

|

| Hepatitis B surface

antigen |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative | 69 | 39 (56.5) | 30 (43.5) | 0.604 |

|

Positive | 68 | 38 (55.9) | 30 (44.1) |

|

| Serum AFP,

µg/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

≤400 | 86 | 47 (54.7) | 39 (45.3) | 0.722 |

|

>400 | 51 | 30 (58.8) | 21 (41.2) |

|

| Tumor size, cm |

|

|

|

|

| ≤5 | 60 | 37 (61.7) | 23 (38.3) | 0.299 |

|

>5 | 77 | 40 (51.9) | 37 (48.1) |

|

| Tumor no. |

|

|

|

|

|

Single | 100 | 63 (63.0) | 37 (37.0) | 0.011b |

|

Multiple | 37 | 14 (37.8) | 23 (62.2) |

|

| Microvascular

invasion |

|

|

|

|

| No | 123 | 66 (53.7) | 57 (46.3) | 0.092 |

|

Yes | 14 | 11 (78.6) | 3

(21.4) |

|

| Liver

cirrhosis |

|

|

|

|

| No | 90 | 48 (53.9) | 41 (46.1) | 0.591 |

|

Yes | 47 | 28 (59.6) | 19 (40.4) |

|

| Differentiation

grade |

|

|

|

|

|

I+II | 74 | 41 (55.4) | 33 (44.6) | 0.864 |

|

III+IV | 63 | 36 (57.1) | 27 (42.9) |

|

| TNM stage |

|

|

|

|

| I | 88 | 55 (62.5) | 33 (37.5) | 0.051 |

|

II+III+IV | 49 | 22 (44.9) | 27 (55.1) |

|

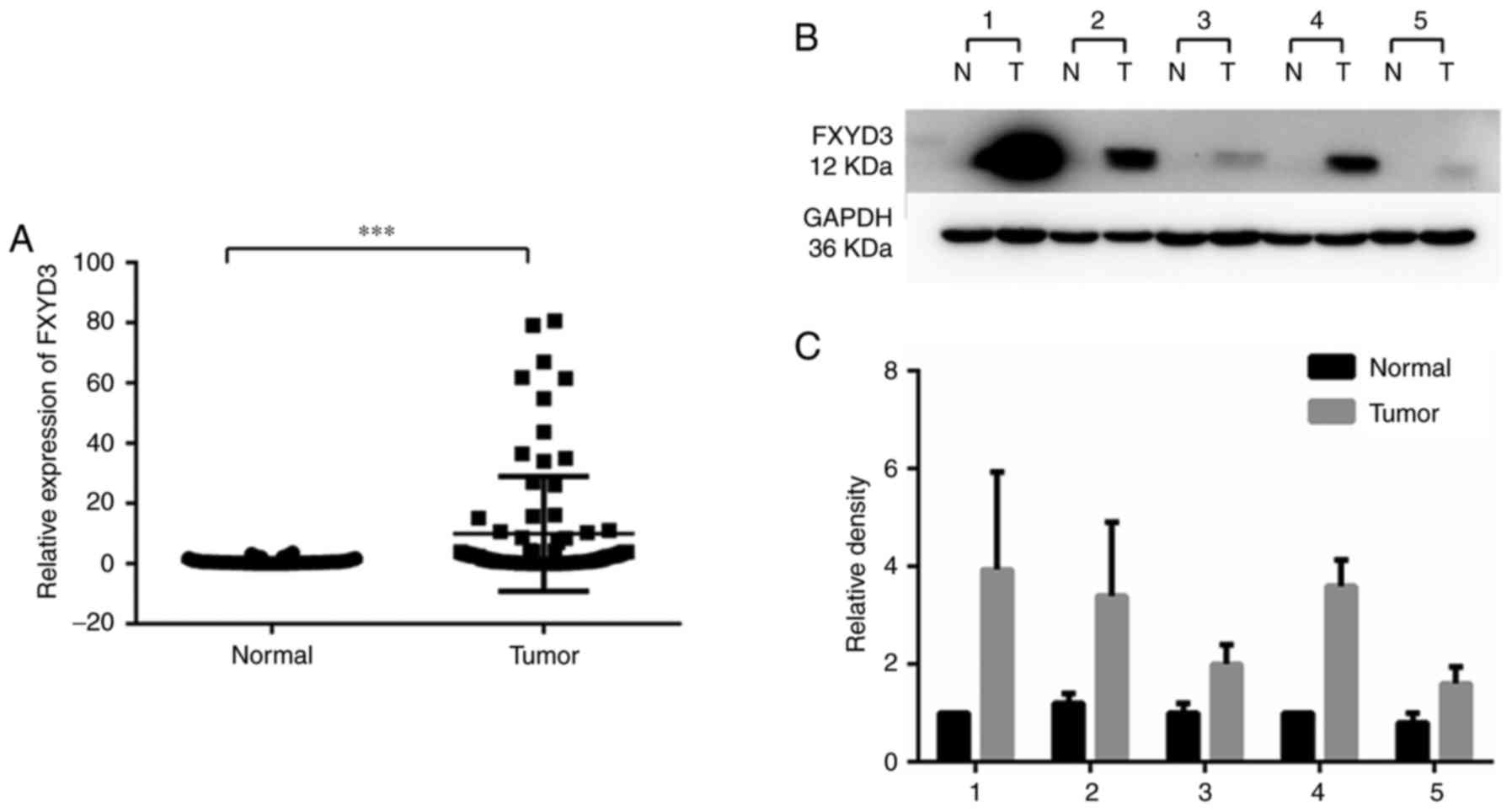

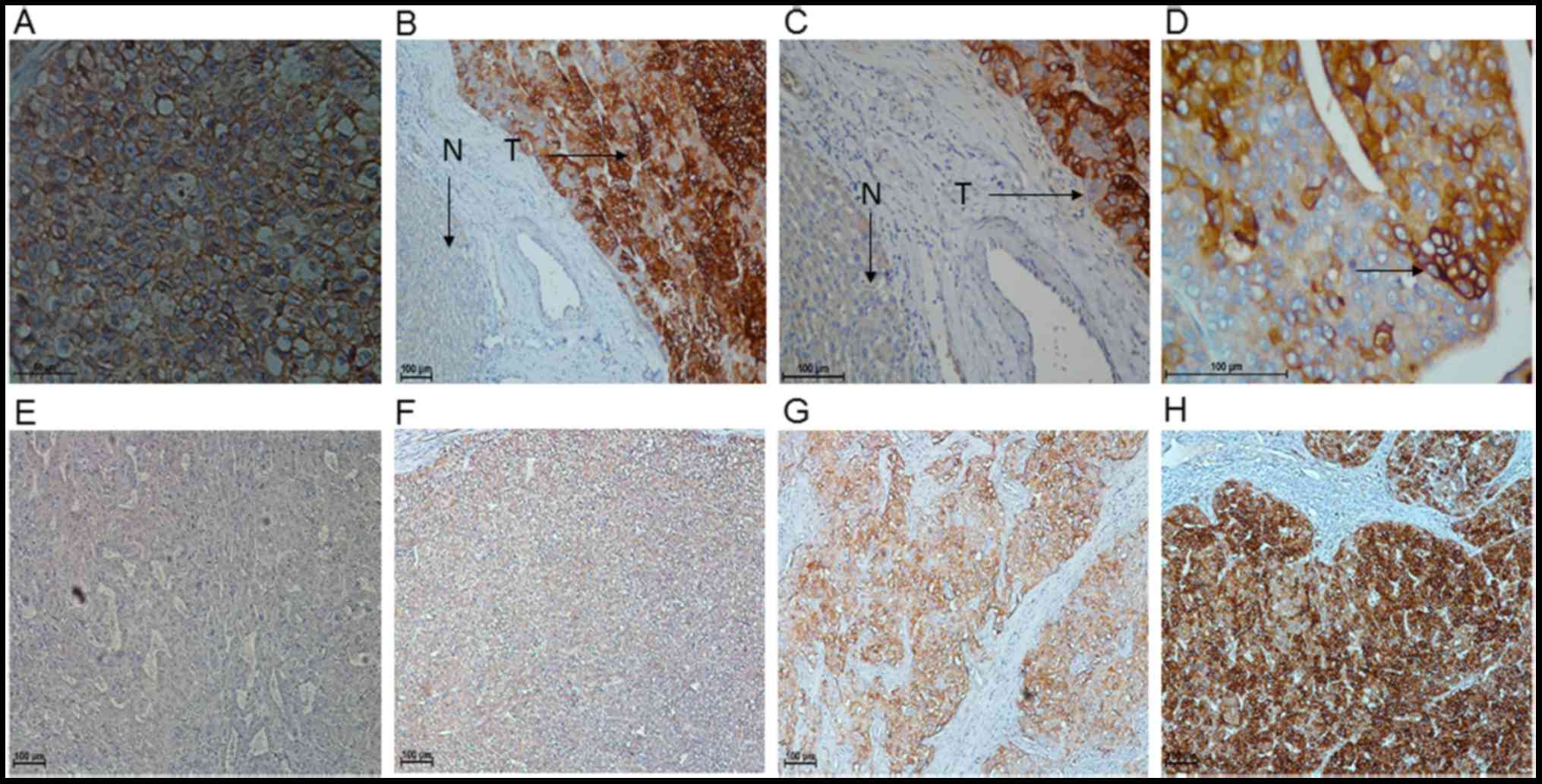

FXYD3 overexpression in HCC

RT-qPCR and western blotting were performed to

analyze the expression of FXYD3 in HCC and non-cancerous liver

tissue samples. This revealed that FXYD3 expression was

significantly elevated in the HCC tissues compared with non-tumor

tissues at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1). Fig.

1B is a representative image of 3 replicates. The western blots

of 5 paired samples (20.8%) showed significant protein expression

and the remaining samples (79.2%) did not exhibit visible

expression. IHC analysis of 137 HCC tissues was used to assess the

function and prognostic significance of FXYD3 in HCC. Positive

staining for FXYD3 was indicated by the presence of brown granules

in the cell membrane and cytoplasm. The specimens were divided into

a high FXYD3 expression group (n=60; 43.8%) and a low FXYD3

expression group (n=77; 56.2%), which exhibited staining ranging

from strongly and moderately positive to weakly positive and

negative, respectively (Fig. 2).

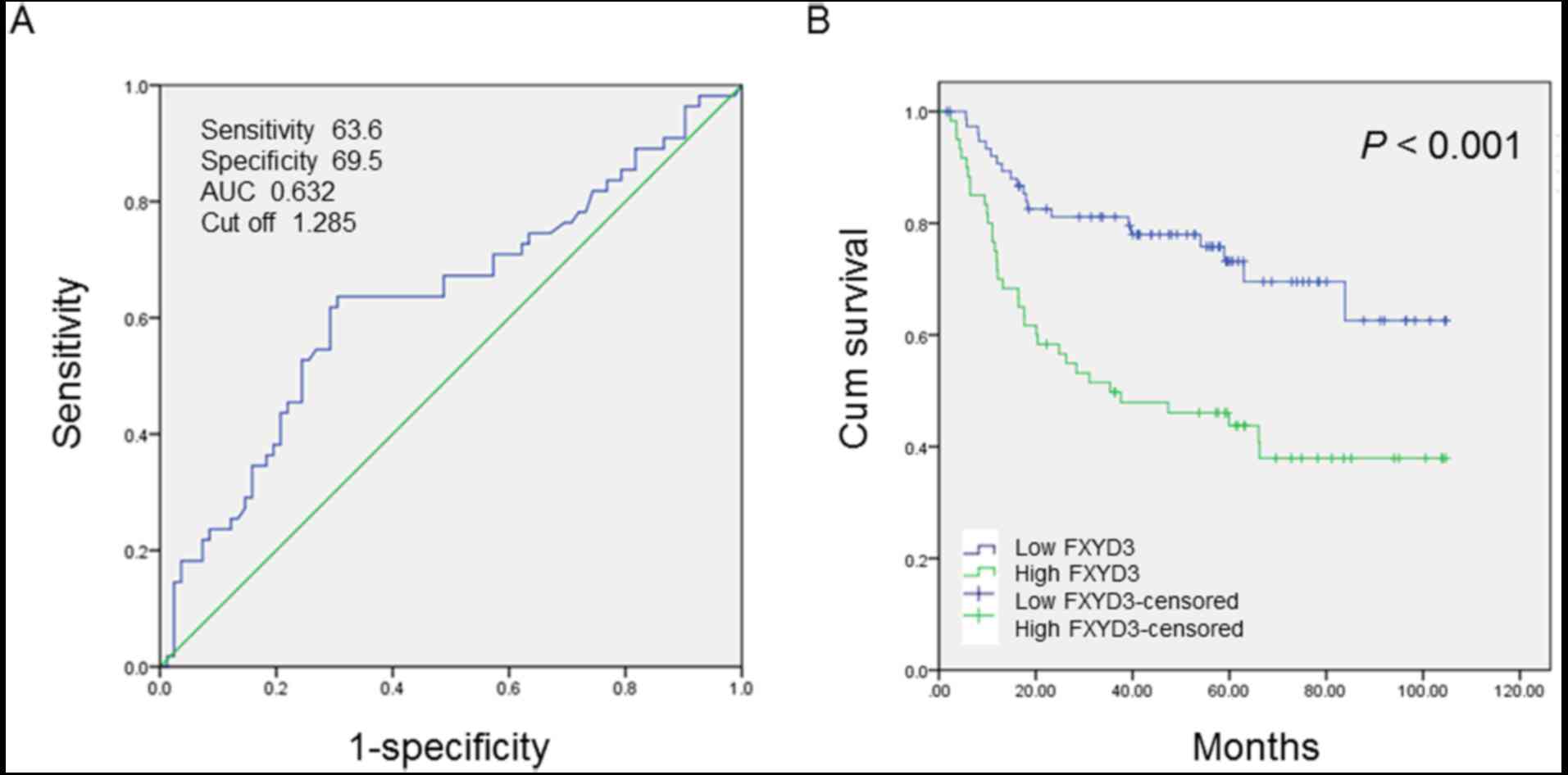

Prognostic significance of FXYD3

protein expression in HCC patients

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

analysis was performed to determine the cutoff score for FXYD3

protein expression. The score closest to the point at which maximum

sensitivity and specificity were displayed was selected as the

cutoff score. The area under the ROC curve was calculated to

estimate the power of FXYD3 to predict the OS rate over the entire

range of scores. According to the ROC curve analysis results

(Fig. 3A), the cohort was classified

into a high expression group and a low expression group to evaluate

the prognostic value of the FXYD3 in HCC patients.

The IHC results were used to evaluate the

association between HCC clinicopathological parameters and FXYD3

expression. The cutoff score (1.285) generated by ROC curve

analysis, was used for classification by high and low FXYD3

expression. Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank test were

performed to analyze the association between FXYD3 protein

expression and OS. OS time was significantly higher in the group

with low FXYD3 expression levels than in the group with high FXYD3

expression levels (P<0.001; Fig.

3B).

Univariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that

FXYD3 expression (P=0.001), tumor size (P=0.007), tumor number

(P<0.001) and tumor stage (TNM) (P<0.001) were significant

risk factors for OS (Table II).

Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that FXYD3

expression (P=0.008), tumor size (P=0.027), and tumor number

(P<0.001) were independent prognostic factors in patients with

HCC (Table II).

| Table II.Prognostic significance of FXYD3

protein in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. |

Table II.

Prognostic significance of FXYD3

protein in hepatocellular carcinoma patients.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| FXYD3 | 2.643 | 1.524–4.582 | 0.001a | 2.137 | 1.224–3.732 | 0.008a |

| Age (years) | 1.146 | 0.673–1.952 | 0.615 |

|

|

|

| Sex | 1.127 | 0.483–2.632 | 0.782 |

|

|

|

| Hepatitis B surface

antigen | 1.013 | 0.434–2.368 | 0.976 |

|

|

|

| Serum AFP | 1.397 | 0.814–2.397 | 0.226 |

|

|

|

| Tumor size | 2.232 | 1.246–3.998 | 0.007a | 1.935 | 1.076–3.480 | 0.027a |

| Tumor number | 5.077 | 2.968–8.683 |

<0.001a | 4.131 | 2.401–7.109 |

<0.001a |

| Microvascular

invasion | 1.996 | 0.901–4.425 | 0.089 |

|

|

|

| Liver

cirrhosis | 1.311 | 0.761–2.260 | 0.330 |

|

|

|

| Differentiation

grade | 1.222 | 1.720–2.074 | 0.457 |

|

|

|

| TNM stage | 4.535 | 2.619–7.855 |

<0.001a |

|

| 0.237 |

Discussion

The predominant clinical staging system for liver

cancer is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system, which is useful

for predicting prognoses and stratifying patients for treatment

(23). A series of predictive

biomarkers, including meprin A subunit α, vascular endothelial

growth factor and insulin-like growth factor-1, have facilitated

improvements in the OS and prognosis for patients with HCC in the

early and advanced stages of the disease when used in combination

with the aforementioned staging system (24–26). The

identification of additional novel predictive markers may

significantly improve patient clinical outcomes.

A series of studies have reported that FXYD3 is

expressed in numerous types of cancer. FXYD3 expression was

initially described in breast cancer (7), and subsequently detected in prostate

cancer, CRC, pancreatic cancer and ESCC, in which FXYD3 was

reported to be significantly upregulated in tumor tissues compared

with normal adjacent mucosal tissues (11–17).

However, in lung cancer and glioma, FXYD3 was demonstrated to be

expressed at low levels compared with healthy paracancerous tissues

(18–20). FXYD3 was originally identified in

murine mammary tumors. Morrison and Leder (6) determined that FXYD3 expression was

induced by the Neu and Ras genes rather than the c-Myc and Int-2

genes. In human mammary epithelial cells, transforming growth

factor-β has been demonstrated to cause downregulation of FXYD3

expression through the zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 pathway

(27,28). In CRC, FXYD3 expression is

hypothesized to be associated with p53 expression, as the FXYD3

promoter contains the p53 binding site. Increased CRC cell

apoptosis, despite p53 mutations, has been demonstrated to be

associated with small interfering FXYD3 (29,30).

However, there is little knowledge regarding the association

between FXYD3 expression and the clinical prognosis of HCC

patients.

The Na+-K+ ATPase is composed

of tetramers of α and β subunits and is located in the plasma

membrane. The channel transports three Na+ ions out of

the cell and two K+ ions into the cell to maintain

cellular homeostasis (31). The

Na+-K+ ATPase has been demonstrated to be

associated with cancer initiation, growth, development and

metastasis (32). It has also been

demonstrated to function in the p38 mitogen-activated protein

kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling cascade, Src

kinase activity, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt/mechanistic target

of rapamycin signaling and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition,

all of which are important pathways in tumorigenesis and tumor

progression (32). Furthermore, it

has been reported that cardiac steroids (cardiac glycosides), which

are potent Na+-K+ pump inhibitors, can

postpone tumor recurrence and metastasis, prolong survival times

and increase survival rates of post-surgical patients with HCC

(33–36). FXYD3 can function as a β-subunit of

the Na+-K+ ATPase and modulate certain cell

functions. However, FXYD3 can also affect glycosylation of the

β-subunit of X, K-ATPase when co-expressed in Xenopus

oocytes (33–35). Glycosylation is closely associated

with tumorigenesis (36,37); however, whether FXYD3-mediated

glycosylation of Na+-K+ ATPase contributes to

HCC growth, invasion and/or metastasis requires investigation in

future studies.

FXYD3 expression was examined at the transcriptional

and translational levels by RT-qPCR, western blotting and IHC.

Using RT-qPCR, it was demonstrated that FXYD3 expression was

significantly elevated in HCC tumor tissues compared with that in

non-cancerous liver tissues. These results were supported by those

achieved through western blotting. It is important to note that

microvascular invasion is a key determinant of prognosis in

patients with HCC. However, the present study indicated no

significant association between FXYD3 expression and microvascular

invasion using χ2 analysis. ROC curve analysis was

performed to identify a cutoff value with which to classify

patients into high or low FXYD3 expression groups. Using

Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank test, it was determined that

FXYD3 expression is associated with OS at the protein level

(P<0.001) and that high FXYD3 expression was predictive of a

poor prognosis in patients with HCC. Univariate and multivariate

Cox regression analyses indicated that FXYD3 protein expression

level was an independent prognostic factor (P=0.008) in patients

with HCC. However, it is possible that bias may have resulted in

group-group differences in survival.

In conclusion, elevated FXYD3 mRNA and protein

expression levels are predictive of poor survival. The present

study partially clarifies the role of FXYD3 in HCC, however, the

precise mechanism underlying the association between the expression

of FXYD3 and HCC remains to be elucidated. Further large

multicenter studies are required to achieve this.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81625017 and 81572385) and

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of

China (grant no. 16ykjc36).

References

|

1

|

Forner A, Llovet JM and Bruix J:

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 379:1245–1255. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

He G, Dhar D, Nakagawa H, Font-Burgada J,

Ogata H, Jiang Y, Shalapour S, Seki E, Yost SE, Jepsen K, et al:

Identification of liver cancer progenitors whose malignant

progression depends on autocrine IL-6 signaling. Cell. 155:384–396.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Li Z, Tuteja G, Schug J and Kaestner KH:

Foxa1 and Foxa2 are essential for sexual dimorphism in liver

cancer. Cell. 148:72–83. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Maluccio M and Covey A: Recent progress in

understanding, diagnosing, and treating hepatocellular carcinoma.

CA Cancer J Clin. 62:394–399. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Morrison BW and Leder P: Neu and ras

initiate murine mammary tumors that share genetic markers generally

absent in c-myc and int-2-initiated tumors. Oncogene. 9:3417–3426.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Morrison BW, Moorman JR, Kowdley GC,

Kobayashi YM, Jones LR and Leder P: Mat-8, a novel

phospholemman-like protein expressed in human breast tumors,

induces a chloride conductance in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem.

270:2176–2182. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhuang L, Xu L, Wang P, Jiang Y, Yong P,

Zhang C, Zhang H, Meng Z and Yang P:

Na+/K+-ATPase α1 subunit, a novel therapeutic

target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 6:28183–28193.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Capendeguy O and Horisberger JD:

Functional effects of Na+, K+-ATPase gene

mutations linked to familial hemiplegic migraine. Neuromolecular

Med. 6:105–116. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Capurro C, Coutry N, Bonvalet JP, Escoubet

B, Garty H and Farman N: Cellular localization and regulation of

CHIF in kidney and colon. Am J Physiol. 271:C753–C762. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Vaarala MH, Porvari K, Kyllönen A and

Vihko P: Differentially expressed genes in two LNCaP prostate

cancer cell lines reflecting changes during prostate cancer

progression. Lab Invest. 80:1259–1268. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Grzmil M, Voigt S, Thelen P, Hemmerlein B,

Helmke K and Burfeind P: Up-regulated expression of the MAT-8 gene

in prostate cancer and its siRNA-mediated inhibition of expression

induces a decrease in proliferation of human prostate carcinoma

cells. Int J Oncol. 24:97–105. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Widegren E, Onnesjö S, Arbman G, Kayed H,

Zentgraf H, Kleeff J, Zhang H and Sun XF: Expression of FXYD3

protein in relation to biological and clinicopathological variables

in colorectal cancers. Chemotherapy. 55:407–413. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Olsen M,

Lowe AW, van Heek NT, Rosty C, Walter K, Sato N, Parker A, Ashfaq

R, et al: Exploration of global gene expression patterns in

pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cDNA microarrays. Am J Pathol.

162:1151–1162. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Friess H, Ding J, Kleeff J, Fenkell L,

Rosinski JA, Guweidhi A, Reidhaar-Olson JF, Korc M, Hammer J and

Büchler MW: Microarray-based identification of differentially

expressed growth- and metastasis-associated genes in pancreatic

cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 60:1180–1199. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Logsdon CD, Simeone DM, Binkley C,

Arumugam T, Greenson JK, Giordano TJ, Misek DE, Kuick R and Hanash

S: Molecular profiling of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and chronic

pancreatitis identifies multiple genes differentially regulated in

pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 63:2649–2657. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhu ZL, Yan BY, Zhang Y, Yang YH, Wang MW,

Zentgraf H, Zhang XH and Sun XF: Overexpression of FXYD-3 is

involved in the tumorigenesis and development of esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Markers. 35:195–202. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gordon GJ, Richards WG, Sugarbaker DJ,

Jaklitsch MT and Bueno R: A prognostic test for adenocarcinoma of

the lung from gene expression profiling data. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev. 12:905–910. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Okudela K, Yazawa T, Ishii J, Woo T,

Mitsui H, Bunai T, Sakaeda M, Shimoyamada H, Sato H, Tajiri M, et

al: Down-regulation of FXYD3 expression in human lung cancers: Its

mechanism and potential role in carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol.

175:2646–2656. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang MW, Gu P, Zhang ZY, Zhu ZL, Geng Y,

Kayed H, Zentgraf H and Sun XF: FXYD3 expression in gliomas and its

clinicopathological significance. Oncol Res. 18:133–139. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Instructions of the Anti-FXYD3 antibody:

Anti-FXYD3 antibody [EPR17160] ab205534. http://www.abcam.com/fxyd3-antibody-epr17160-ab205534.html

|

|

23

|

Llovet JM, Brú C and Bruix J: Prognosis of

hepatocellular carcinoma: The BCLC staging classification. Semin

Liver Dis. 19:329–338. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

OuYang HY, Xu J, Luo J, Zou RH, Chen K, Le

Y, Zhang YF, Wei W, Guo RP and Shi M: MEP1A contributes to tumor

progression and predicts poor clinical outcome in human

hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 63:1227–1239. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kaseb AO, Hassan MM, Lin E, Xiao L, Kumar

V, Pathak P, Lozano R, Rashid A, Abbruzzese JL and Morris JS:

V-CLIP: Integrating plasma vascular endothelial growth factor into

a new scoring system to stratify patients with advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma for clinical trials. Cancer.

117:2478–2488. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kaseb AO, Abbruzzese JL, Vauthey JN, Aloia

TA, Abdalla EK, Hassan MM, Lin E, Xiao L, El-Deeb AS, Rashid A and

Morris JS: I-CLIP: Improved stratification of advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma patients by integrating plasma IGF-1 into

CLIP score. Oncology. 80:373–381. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yamamoto H, Mukaisho K, Sugihara H,

Hattori T and Asano S: Down-regulation of FXYD3 is induced by

transforming growth factor-β signaling via ZEB1/δEF1 in human

mammary epithelial cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 34:324–329. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Herrmann P and Aronica SM: Estrogen and

tamoxifen up-regulate FXYD3 on breast cancer cells: Assessing the

differential roles of ER α and ZEB1. SpringerPlus. 4:2452015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bibert S, Aebischer D, Desgranges F, Roy

S, Schaer D, Kharoubi-Hess S, Horisberger JD and Geering K: A link

between FXYD3 (Mat-8)-mediated Na,K-ATPase regulation and

differentiation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol

Cell. 20:1132–1140. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Maxwell PJ, Longley DB, Latif T, Boyer J,

Allen W, Lynch M, McDermott U, Harkin DP, Allegra CJ and Johnston

PG: Identification of 5-fluorouracil-inducible target genes using

cDNA microarray profiling. Cancer Res. 63:4602–4606.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kanai R, Ogawa H, Vilsen B, Cornelius F

and Toyoshima C: Crystal structure of a Na+-bound

Na+,K+-ATPase preceding the E1P state.

Nature. 502:201–206. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Durlacher CT, Chow K, Chen XW, He ZX,

Zhang X, Yang T and Zhou SF: Targeting

Na+/K+-translocating adenosine triphosphatase

in cancer treatment. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 42:427–443. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Crambert G, Li C, Claeys D and Geering K:

FXYD3 (Mat-8), a new regulator of Na, K-ATPase. Mol Biol Cell.

16:2363–2371. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yue Q, Zhen H, Huang M, Zheng X, Feng L,

Jiang B, Yang M, Wu W, Liu X and Guo D: Proteasome inhibition

contributed to the cytotoxicity of arenobufagin after its binding

with Na, K-ATPase in human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells. PLoS One.

11:e01590342016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen Z, Chen HY, Lang QB, Li B, Zhai XF,

Guo YY, Yue XQ and Ling CQ: Preventive effects of jiedu granules

combined with cinobufacini injection versus transcatheter arterial

chemoembolization in post-surgical patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma: A case-control trial. Chin J Integr Med. 18:339–344.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hart GW and Copeland RJ: Glycomics hits

the big time. Cell. 143:672–676. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Dalziel M, Crispin M, Scanlan CN, Zitzmann

N and Dwek RA: Emerging principles for the therapeutic exploitation

of glycosylation. Science. 343:12356812014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|