Introduction

Approximately one million new cases of early gastric

cancer are reported annually and account for 6.9% of all newly

reported cancer cases (1). Gastric

cancer ranks the fifth worldwide and is the third leading cause of

cancer-related death after lung, breast, colorectal and prostate

cancer (1,2).

According to the depth of infiltration, gastric

cancer is defined as limited infiltration to mucosa or submucosa,

with or without lymphatic metastasis (3). Scholars in Japan and other countries

consider that early detection and treatment is the most effective

way to improve the prognosis of gastric cancer (4,5). Although

gastroscopy is safe for the general population, the application of

gastroscopy in patients with chronic hypertension may cause

arrhythmia, myocardial infarction and complications (6). Therefore, painless gastroscopy can be

performed for patients with chronic hypertension under sedative

conditions to reduce the pain and the incidence of restless

situation.

The current study was carried out to compare the

safety of the application of painless gastroscopy and ordinary

gastroscopy in chronic hypertension patients combined with early

gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

Materials

A total of 123 patients with suspected early gastric

cancer were selected at the Dongying People's Hospital (Shandong,

China) from June, 2014 to August, 2016. The current study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongying People's Hospital.

Signed written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Patients were randomly divided into the painless

gastroscopy (n=63) and ordinary gastroscopy (n=60) groups. Patients

in the painless gastroscopy group included 30 males and 33 females,

with an average age of of 54.7±7.1 years. Patients in the ordinary

group included 29 males and 31 females, with an average age of

52.7±6.8 years. There was no significant difference in sex, age,

early symptoms of gastric cancer and the history of hypertension

between the two groups (P>0.05) (Table

I).

| Table I.Comparison of general information of

the two groups. |

Table I.

Comparison of general information of

the two groups.

|

|

|

| Sex | Symptoms (cases) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Groups | n | Age years | Male | Female | Anorexia | Nausea and

vomitting | Hematemesis

melena | History of

hypertension (years) |

|---|

| Painless

gastroscopy | 63 | 54.7±7.1 | 30 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 1 | 11.3±6.1 |

| Ordinary

gastroscopy | 60 | 52.7±6.8 | 29 | 31 | 32 | 26 | 2 | 10.5±5.6 |

| t/χ2 | – | 8.72 | 10.11 |

| 12.34 | 8.68 | 9.02 | 13.13 |

| P-value | – | 0.09 | 0.39 |

| 0.28 | 1.02 | 0.58 | 0.34 |

General preparation

Preoperative preparation was performed for all the

patients. Anesthesia and anesthesia-related complications were also

explained to the patients. All the patients signed informed

consent. Medical history was checked and clinical examination was

performed to exclude disease of heart, brain and other vital

organs. Patients were fasted for 8 h and deprivation was performed

for 6 h. Gastroscope, ECG monitor, mask, oxygen supplies and

narcotic drugs were prepared.

Operation methods

Patients were fasted for 8 h and deprivation was

performed for 4 h before treatment. Oral administration of

dacronine hydrochloride (Yangtze River Pharmaceutical Group, Ltd.,

Jiangsu, China) was performed before gastroscopy for mucosal

lubrication and anesthesia. Patients were fixed in left lateral

position, and vital signs were checked. Patients in the painless

gastroscopy were given balanced anesthesia before gastroscopy, and

the specific method employed was: Remifentanil (Yichang Renfu

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Hubei, China) at a dose of 0.5–1 µg/kg

and propofol (Beijing Fresenius Kabi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.,

Beijing, China) at a dose of 1.5–2 mg/kg through slow intravenous

injection. Gastroscopy was performed when patients lost

consciousness, relevant reflex disappeared, and muscle relaxed.

Proper drug treatment was performed according to the conditions.

When endoscope mirror body reached the descendant duodenum, images

were captured and examination was stopped. Patients were asked not

to intake any food and only intake liquid diet 2 h after operation.

Balanced anesthesia was not performed for patients in the ordinary

gastroscopy group.

Observation indicators

Changes in arterial pressure, heart rate, and blood

oxygen saturation were recorded and compared before anesthesia,

when the gastroscope passed through the esophageal entrance plane,

and after recovery from anesthesia. The incidence of adverse

reactions including nausea, vomiting, cough, dysphoria and throat

discomfort were recorded and compared.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 11.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago,

IL, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Measurement data

were expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were

performed using t-test. Countable data were compared using the

χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant analysis.

Results

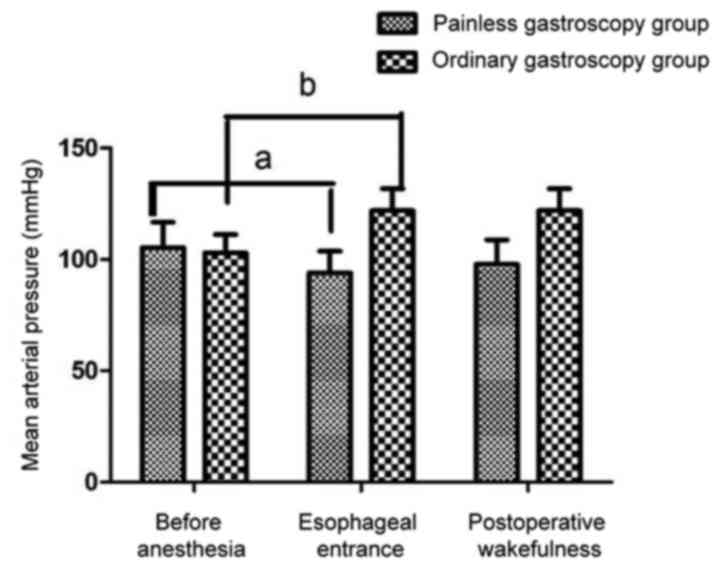

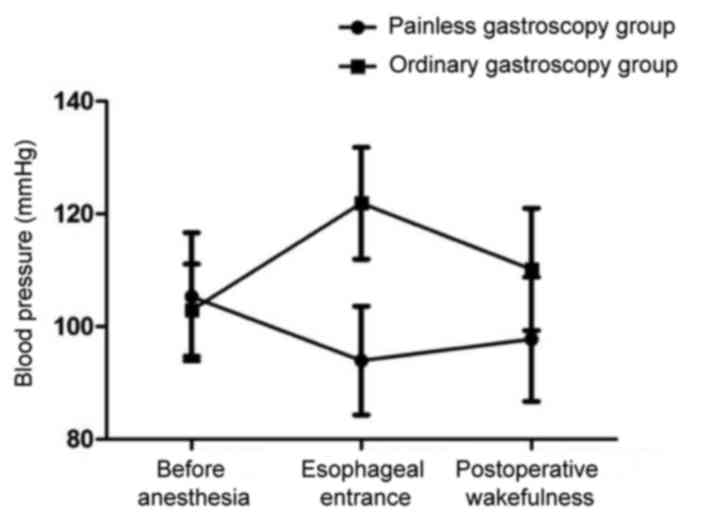

Comparison of mean arterial pressure,

heart rate and blood oxygen saturation between the two groups at

different time points

Mean arterial pressure, heart rate and blood oxygen

saturation were significantly reduced in painless gastroscopy when

the gastroscope passed through the esophageal entrance plane

compared with the levels of those factors before anesthesia

(P<0.05). In the ordinary gastroscopy group, compared with the

levels before anesthesia, the mean arterial pressure, heart rate

and blood oxygen saturation were significantly increased when the

gastroscope passed through the esophageal entrance plane

(P<0.05). Blood pressure decreased in the painless gastroscopy

group and increased in the ordinary gastroscopy group after

anesthesia. The decrease in the painless gastroscopy group was

lower than the increase in the ordinary group (Figs. 1–4).

Comparison of intra- and postoperative

adverse reactions between the two groups

The incidence of intra- and postoperative adverse

reactions including nausea, vomiting, cough, dysphoria, throat

discomfort and other adverse reactions was significantly lower in

the painless gastroscopy group compared with the ordinary

gastroscopy group (P<0.05). Thus, painless gastroscopy can

reduce the incidence of postoperative adverse reactions (Table II).

| Table II.Comparison of intraoperative and

postoperative adverse reactions between the two groups [n (%)]. |

Table II.

Comparison of intraoperative and

postoperative adverse reactions between the two groups [n (%)].

| Groups | Nausea | Vomiting | Throat

discomfort | Cough | Dysphoria |

|---|

| A | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.8) | 0 | 0 |

| B | 60 | 43 (71.7) | 60 | 48 (80) | 25 (41.7) |

| P-value | 0.047 | 0.038 | 0.026 | 0.034 | 0.049 |

Comparison of the degree of tolerance

between the two groups

The number of patients showing no discomfort to

gastroscopy was significantly smaller in the painless gastroscopy

than in the ordinary gastroscopy (P<0.05) (Table III).

| Table III.Comparison of degree of tolerance

between the two groups [n (%)]. |

Table III.

Comparison of degree of tolerance

between the two groups [n (%)].

|

|

| Discomfort |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Groups | Unbearable | Obviously | Minor |

|---|

| Painless gastroscopy

group | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Ordinary gastroscopy

group | 15 (25) | 30 (50) | 15v25 |

| P-value | 0.030 | 0.042 | 0.021 |

Discussion

Employing gastroscopy is imperative in the diagnosis

of gastric and upper gastrointestinal diseases, such as bleeding

and ulcers. Due to its invasive nature, gastroscopy leads to pain

in patients (7). Under ordinary

gastroscopy, local irritation caused by the endoscope can induce

nausea and vomiting. In addition, the effects of the

hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cortical system lead to, a series of

changes in vital signs of the body (8). Previous findings have shown that

gastroscopy may cause a series of complications in patients with

hypertension, such as myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest and

other complications (9). The

development of endoscopic technology, has led to an increase in the

diagnostic rate of early gastric cancer. However, the incidence of

hypertension is also on the increase. Therefore, the safe use of

this technique has become a focus of current research. The use of

painless gastroscopy, not only significantly reduces pain, but can

also facilitate the diagnosis of gastric cancer.

The morbidity and mortality of gastric cancer are

only lower to lung cancer (10,11).

Additionally, early diagnosis is closely related to the prognosis

of patients (12). Propofol used in

balanced anesthesia before painless gastroscopy can induce

anesthesia rapidly, and the recovery is fast. Propofol can also

inhibit nausea and vomiting. Nevertheless propofol has certain

inhibitory effects on the respiratory and circulatory system,

inducing a decrease in blood pressure and heart rate, albeit these

effects are related to the dose administered (13). Remifentanil is a potent opioid

receptor agonist with rapid action (14,15). The

combined use of propofol and remifentanil utilizes the advantages

of both to maintain vital signs and reduce unnecessary adverse

reactions, in order to facilitate gastroscopy (16–18).

Previous findings have shown that the incidence of

digestive diseases is high in patients with chronic hypertension.

In patients older than 45 years, the risk of cardiovascular disease

can be increased by 2-fold by an increase of 20 mmHg in systolic

blood pressure and 10 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure (19,20). In

patients with chronic hypertension, blood pressure is altered

during gastroscopy, which in turn increases the incidence of

cerebrovascular disease. In the present study, an increase in blood

pressure and heart rate was observed in the ordinary gastroscopy

group, whereas, the drug used in the painless gastroscopy group

reduced the blood pressure. Mean arterial pressure, heart rate and

blood oxygen saturation were significantly reduced in painless

gastroscopy when the gastroscope passed through the esophageal

entrance plane compared with the levels of those factors before

anesthesia (P<0.05). In the ordinary gastroscopy group, compared

with the levels before anesthesia, mean arterial pressure, heart

rate and blood oxygen saturation were significantly increased when

the gastroscope passed through the esophageal entrance plane

(P<0.05). No obvious discomfort, nausea, vomiting, cough,

dysphoria, or pharyngeal discomfort was found in the painless

gastroscopy group.

In conclusion, painless gastroscopy is safer, and

more comfortable and effective for chronic hypertension patients

combined with early gastric cancer. However, contraindications

should be checked and vital signs should be monitored to reduce the

intra- and postoperative bleeding caused by surgery. The

application of painless gastroscopy can significantly increase the

diagnostic rate of early gastric cancer. However, the circulation

should be maintained to reduce complications of anesthesia.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser

S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D and Bray F: Cancer

incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major

patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 136:359–386. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Katai H and Sano T: Early gastric cancer:

Concepts, diagnosis, and management. Int J Clin Oncol. 10:375–383.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Crew KD and Neugut AI: Epidemiology of

gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 12:354–362. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tsubono Y and Hisamichi S: Screening for

gastric cancer in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 3:9–18. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yeoh KG: How do we improve outcomes for

gastric cancer? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 22:970–972. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ross R and Newton JL: Heart rate and blood

pressure changes during gastroscopy in healthy older subjects.

Gerontology. 50:182–186. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Maki S, Yao K, Nagahama T, Beppu T, Hisabe

T, Takaki Y, Hirai F, Matsui T, Tanabe H and Iwashita A: Magnifying

endoscopy with narrow-band imaging is useful in the differential

diagnosis between low-grade adenoma and early cancer of superficial

elevated gastric lesions. Gastric Cancer. 16:140–146. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Miskovitz P: Sleisenger & Fordtran's

gastrointestinal and liver

disease-pathophysiology/diagnosis/management. Gastrointest Endosc.

49:A21999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Takeno S, Hashimoto T, Maki K, Shibata R,

Shiwaku H, Yamana I, Yamashita R and Yamashita Y: Gastric cancer

arising from the remnant stomach after distal gastrectomy: A

review. World J Gastroenterol. 20:13734–13740. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fujiwara S, Yao K, Nagahama T, Uchita K,

Kanemitsu T, Tsurumi K, Takatsu N, Hisabe T, Tanabe H, Iwashita A,

et al: Can we accurately diagnose minute gastric cancers (≤5 mm)?

Chromoendoscopy (CE) vs magnifying endoscopy with narrow band

imaging (M-NBI). Gastric Cancer. 18:590–596. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tao G, Xing-Hua L, Ai-Ming Y, Wei-Xun Z,

Fang Y, Xi W, Li-Yin W, Chong-Mei L, Gui-Jun F, Hui-Jun S, et al:

Enhanced magnifying endoscopy for differential diagnosis of

superficial gastric lesions identified with white-light endoscopy.

Gastric Cancer. 17:122–129. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Disma N, Astuto M, Rizzo G, Rosano G, Naso

P, Aprile G, Bonanno G and Russo A: Propofol sedation with fentanyl

or midazolam during oesophagogastroduodenoscopy in children. Eur J

Anaesthesiol. 22:848–852. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dias-Silva D, Pimentel-Nunes P, Magalhaes

J, Magalhaes R, Veloso N, Ferreira C, Figueiredo P, Moutinho P and

Dinis-Ribeiro M: The learning curve for narrow-band imaging in the

diagnosis of precancerous gastric lesions by using web-based video.

Gastrointest Endosc. 79:910–920. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Numata N, Oka S, Tanaka S, Kagemoto K,

Sanomura Y, Yoshida S, Arihiro K, Shimamoto F and Chayama K: Risk

factors and management of positive horizontal margin in early

gastric cancer resected by en bloc endoscopic submucosal

dissection. Gastric Cancer. 18:332–338. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto

K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H and Otsuji E: Long-term outcomes of

patients who underwent limited proximal gastrectomy. Gastric

Cancer. 17:141–145. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ozcelik M, Guclu C, Bermede O, Baytas V,

Altay N, Karahan MA, Erdogan B and Can O: The administration

sequence of propofol and remifentanil does not affect the ED50 and

ED95 of rocuronium in rapid sequence induction of anesthesia: A

double-blind randomized controlled trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol

Sci. 20:1479–1489. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hwang SW and Lee DH: Is endoscopic

ultrasonography still the modality of choice in preoperative

staging of gastric cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 20:13775–13782.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao P, Xiao SM, Tang LC, Ding Z, Zhou X

and Chen XD: Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition and

TGRY anastomosis for proximal gastric cancer. World J

Gastroenterol. 20:8268–8273. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Amornyotin S, Lertakayamanee N,

Wongyingsinn M, Pimukmanuskit P and Chalayonnavin V: The

effectiveness of intravenous sedation in diagnostic upper

gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Med Assoc Thai. 90:301–306.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|