Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most malignant types of

gynecological cancer, and is the 11th most common type of cancer

among women, as well as the 5th leading cause of cancer-associated

mortality in the USA (1). In

addition, ovarian cancer is the leading cause of gynecological

malignancy-associated mortality (1,2). The

American Cancer Society estimated there were 22,530 new cases of

ovarian cancer and 13,980 mortalities from ovarian cancer in the

USA in 2019 (1). Furthermore, the

incidence of new ovarian cancer cases has been decreasing on

average by 2.5% each year in the past decade; however, the overall

survival rate has not improved in recent years (2). The current 5-year survival rate for all

the stages of ovarian cancer cases in the US is approximately 47%

(1). However, approximately 60% of

the new cases are diagnosed at advanced stages, and in those cases,

the 5-year survival rate is only 29% (1). Moreover, there is a high rate of

recurrence even after aggressive multimodal treatment, which

further worsens the prognosis (3).

Ovarian cancer belongs to a group of heterogeneous

tumors that arise spontaneously largely from the ovaries, but may

evolve from various other potential sources (4–6). In

addition, ovarian cancer can be morphologically classified into

epithelial and non-epithelial types, of which 80–90% of all ovarian

cancer cases are epithelial type (5). Based on their aggressiveness,

epithelial ovarian cancers (EOCs) are further subdivided into high-

and low-grade categories; or morphologically, they are subdivided

into serous, endometrioid, mucinous and clear cell varieties

(7,8). High-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC)

accounts for 50–60% of all ovarian neoplasms (8). Furthermore, advanced HGSOC accounts for

approximately 50% of all EOCs (7–9), but the

precise etiological factors underlying ovarian cancer have not been

fully elucidated. However, hereditary susceptibility is considered

an important risk factor, as approximately 35% of HGSOC cases

harbor a germline mutation of the tumor suppressor genes Breast

cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1) or BRCA2

(10).

The current therapeutic measure used to treat

ovarian cancer is a multimodal regimen, and a combination of

platinum and paclitaxel is used as the primary chemotherapeutic

regimen (11). However, the relapse

rate remains high due to chemoresistance (12). Poly ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitor

(PARPi) has been introduced as a promising therapeutic agent to

improve the prognosis of HGSOC (13). Olaparib is the most commonly used

PARPi, and exhibits favorable outcomes in lowering disease

progression and mortality rates (14). Moreover, olaparib has been approved

by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the first monotherapy

to combat advanced epithelial ovarian cancer cases harboring

germline BRCA mutations (15).

IQ motif containing GTPase Activating Proteins

(IQGAPs) are a family of GTPase activating proteins, which

have been evolutionarily conserved from yeast to mammals (16,17). In

a review by Hedman et al (18), the varied functions of IQGAPs,

in addition to serving as scaffolding proteins are discussed. In

total, three members of the IQGAP family have been described

in humans (18). Furthermore, all

three members are equipped with four IQ motifs and a Ras

GTPase-activating protein (GAP)-related domain (18); the GAP-related domain of

IQGAPs mediates its binding to the Rho family of GTPases

(19). A member of the Rho family of

GTPases, Cell Division Cycle 42 (CDC42) has been revealed to

serve critical roles in cell proliferation, survival, adhesion and

migration, and is correlated with a less favorable prognosis in

various types of cancer (20–23). Of

the three IQGAP family members, IQGAP1 has been

reported to play a synergistic role in cancer progression and aid

in cellular motility (24–26). However, IQGAP2 exhibits a

tumor suppressive function (26).

Moreover, IQGAP3 is hypothesized to be involved in the

proliferation of epithelial cells (27), and is a novel member of the

IQGAP family, which was discovered in 2007 (28). IQGAP3 is located on chromosome

1 at 1q21.3 loci and has been reported to act as an oncogene in

several types of cancer (29–35).

Furthermore, IQGAP3 is a transmembrane protein, and has been

speculated to be a potential therapeutic target (35).

The present study aimed to analyze the differential

expression of IQGAP3 in HGSOC and healthy tissues, and the

effect of IQGAP3 knockdown on various functional processes,

such as cell proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis, to

determine whether IQGAP3 could serve as a potential

oncogenic prognostic and therapeutic target for patients with

HGSOC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

A total of 149 ovarian cancer tissue samples

(patient age range, 34–79 years; median age, 56 years) and 64

healthy fallopian tube epithelial tissues (patient age range, 26–74

years; median age, 47 years) with detailed clinical information

were collected from the Pathology Department at Qilu Hospital of

Shandong University (Ji'nan, China) between January 2005 and

January 2015. All the malignant samples were diagnosed in

accordance with the International Federation of Gynecology and

Obstetrics criteria (36). The

healthy samples were collected from patients who underwent surgery

for benign conditions. Signed consents were collected from all the

patients and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu

Hospital of Shandong University.

Survival analysis was performed on datasets from the

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including 523 patients for

overall survival analysis using datasets GSE18520 (37), GSE26193 (38), GSE30161 (39), GSE63885 (40) and GSE9891 (41), and 483 patients for the

progression-free survival analysis using datasets GSE26193,

GSE30161, GSE63885, GSE9891, GSE65986 (42) on Kaplan-Meier Plotter (43).

Cell lines and cell culture

Human ovarian cancer cells A2780 (cat. no. CL-0013;

Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (100

IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (all Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). HEY cells (gifted from Dr Jianjun Wei;

Laboratory at Northwestern University) were cultured in DMEM

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS.

All the cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C

with 5% CO2.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC staining of the tissue microarray (TMA) was

performed on 4-µm sections sliced from each TMA receiver block

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 48 h and

embedded in paraffin. Tissue slides were deparaffinized in xylene

and rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (10 min each in 100,

95, 80 and 70% ethanol). Antigen retrieval was performed using a

heat-induced epitope retrieval method with 10 mmol/l EDTA buffer

(pH 8.0) at 98°C for 15 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was

quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min at 37°C,

and non-specific binding was blocked by incubation with donkey

serum as part of the SP9000 IHC kit (OriGene Technologies, Inc.;

cat. no. SP9000) for 30 min at 37°C. The slides were subsequently

incubated overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber with

anti-IQGAP3 (Abcam; cat. no. ab219354) antibody at a

dilution of 3 µg/ml. Staining was visualized using I–View

3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining detection system (OriGene

Technologies, Inc.; cat. no. ZLI-9018). The IHC score was

determined using a semi-quantitative method based on the extent and

intensity of positively stained cells. The percentage of positive

cells within each sample was scored independently from 0 to 100%

upon observation under a light microscope (magnification, ×10). The

intensity of immunostaining was graded as follows: 0, Negative; 1,

weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong. The final IHC score was generated

by multiplying the percentage extent with the staining intensity

score. Then, two gynecological pathologists independently reviewed

the IHC staining. High IQGAP3 expression grade was defined

as a final IHC score ≥100.

Stable and transient transfection

For stable transfection, lentiviral vector GV493

(hU6-MCS-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin) was packaged with IQGAP3

short hairpin (sh)RNA along with the respective negative control

(NC), which were purchased from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. A total

of 1×105 cells were plated into 6-well plates 24 h prior

to stable transfection. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) was

determined and the lentivirus was added to the culture medium

complemented with the transfection reagent HiTransGA (Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd.) with a MOI value of 20–50. After 24 h

incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium

containing 2 µg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for

selection of the stably transfected colonies.

Transient transfection was performed using small

interfering (si)RNAs purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.

at a concentration of 20 µM. RNAi-mediated knockdown was performed

with the following siRNAs: si-IQGAP3−1,

5′-GGCAGAAACUAGAAGCAUA-3′; si-IQGAP3−2,

5′-GAGCCAACCAGGACACUAA-3′; si-CDC42,

5′-GGACGGAUUGAUUCCACAU-3′; and si-NC, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′.

Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The subsequent experiments were performed

24–48 h after transfection.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples and

cultured cells using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

mRNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript cDNA

Synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h and then at 85°C

for 5 min according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was

performed using SYBR-Green Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio, Inc.) with

a StepOne Plus RT PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The reaction conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec, followed by 40 cycles of annealing

at 60°C for 10 sec and an extension at 72°C for 30 sec. β-actin was

used as the endogenous control. The primers were designed based on

the GeneBank sequences. The primer sequences used were:

IQGAP3 forward, 5′-GTGCAGCGGATCAACAAAGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-ACGATGCAACAGGGTACACTG-3′; and β-actin forward,

5′-GAGGCACTCTTCCAGCCTTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGATGTCCACGTCACATTC-3′.

The comparative threshold cycle method, 2−ΔΔCq, was used

to calculate the relative gene expression level (44).

Western blotting

Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) with PMSF (1%) and NaF (1%).

Protein samples were incubated for 30 min on ice and cell debris

were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The

protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid

assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein samples (30 µg)

were separated by SDS-PAGE (5% stacking gel and 10% separating gel)

and transferred to a PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore) using a Bio-Rad

Trans-blot system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). After blocking with

5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was

incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies. The

membranes were then rinsed with TBST (0.1% Tween-20) followed by

incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary

antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were detected using

enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer, Inc.) with ImageQuant LAS

4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). β-actin was used as the

endogenous control. Densitometry analysis was performed using

ImageJ version 1.52 g (National Institutes of Health).

The antibodies used were: Rabbit anti-human

IQGAP3 (1:1,000; Abcam; cat. no. ab219354), rabbit

anti-human CDC42 (1:1,000; Affinity Biosciences; cat. no.

DF6322), rabbit anti-human Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 1

(ZEB-1; 1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

3396), rabbit anti-human N-cadherin (N-CAD; 1:1,000; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 13116), rabbit anti-human E-cadherin

(E-CAD; 1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 3195),

rabbit anti-human Vimentin (1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 5741), rabbit anti-human Snail (1:1,000;

CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 3879), rabbit anti

phospho-(p-)AKT (1:1,000; Abcam; cat. no. ab66138), rabbit

anti-human AKT (1:1,000; Abcam; cat. no. ab179463), rabbit

anti-human PI3K (1:1,000; Abcam; ab182651), rabbit

anti-human phosphorylated (p-)mTOR (1:1,000; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 2971), rabbit anti-human mTOR

(1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 2983), rabbit

anti-human Bcl2 (1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. 2876), rabbit anti-human caspase3 (1:1,000; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 8G10), rabbit anti-human p-ATM

Serine/Threonine Kinase (1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. 5883), rabbit anti-human ATM (1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 2873), rabbit anti-human

Checkpoint Kinase 2 (CHK2; 1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 2662), rabbit anti-human RAD51

(1:10,000; Abcam; cat. no. ab133534) mouse anti-human Bax

(1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 2772), mouse

anti-human caspase9 (1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. 9508), rabbit anti-human Pgp (1:1,000; Abcam; cat.

no. ab103477) and mouse anti-human β-actin (1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 3700).

The secondary antibodies used were: Horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA; cat. no. A0545) or anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:5,000;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. A9044).

Cell proliferation assay

The proliferative ability of cells was measured

using an MTT assay. Each cell line was seeded in quintuplicate into

96-well plates (0.8–1×103 cells/well) for 0–4 days. At

specified time points, 20 µl MTT reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) at 5 mg/ml concentration was added to each well, and the

cells were incubated for an additional 3.5 h at 37°C. Subsequently,

the supernatants were discarded and 100 µl DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) was added to each well. The absorbance at 490 nm was

measured using a Varioskan Flash microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell migration and invasion were analyzed using

Boyden chamber-style cell culture inserts, with and without

Matrigel (BD Biosciences), respectively. Matrigel was thawed at 4°C

and then coated onto the Transwell inserts, after which the gel was

allowed to set at 37°C for 1 h. Ovarian cancer cells

(2×105 cells) were seeded in the upper chamber of the

Transwell inserts (24-well plate; 8-µm pore size; BD Biosciences)

with 200 µl serum-free media. The lower chambers were filled with

700 µl culture media containing 10% FBS as the chemoattractant.

After 6–48 h of incubation, the cells on the lower surface of the

membrane were washed with PBS and fixed in 100% methanol for 15 min

at room temperature. Then, cells were stained with 0.1% crystal

violet for 20 min at room temperature to quantify migration and

invasion. Transwell inserts were observed under a light microscope

(magnification, ×10) and cells in 10 random fields were

counted.

Clonogenic assay

For the colony formation assay, 500 cells were

seeded into each well of a 6-well plate and maintained in media

containing 10% FBS at optimum conditions of 37°C with 5%

CO2 for 10–14 days, until the colonies became visible to

the naked eye. Colonies were then fixed with 100% methanol at room

temperature for 15 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room

temperature. Colonies with >50 cells were counted manually under

a light microscope (magnification, ×10) for quantification.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected using an Annexin V-FITC and

propidium iodide (PI) kit (BD Biosciences), according to the

manufacturer's protocol. A2780 and HEY cells were transfected with

20 µM si-IQGAP3 or si-NC, and were harvested 48 h after

transfection with EDTA-free trypsin, centrifuged at 800 × g for 5

min at room temperature, washed twice with cold PBS, resuspended at

a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml and mixed with 100 µl

1X binding buffer. Subsequently, cells were stained with 5 µl

Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl PI at room temperature for 15 min in the

dark, after which 300 µl 1X binding buffer was added and the cells

were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences)

within 1 h. The results were analyzed using FlowJo software version

X.0.7 (FlowJo, LLC).

Cell viability assay

A total of 2×103 cells/well were seeded

in 96-well plates. The A2780 and HEY cells were exposed to olaparib

(Selleck Chemicals; cat. no. AZD2281) at various final

concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 µmol/ml) at 37°C for 36–72

h. Each concentration was repeated in quintuplicate wells.

Subsequently, 20 µl 5 mg/ml MTT was added to each well. After

incubation for 3.5 h, the medium was replaced with 100 µl DMSO, and

cell viability was determined by analyzing the absorbance values at

490 nm on a Varioskan Flash microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Mouse xenograft models

HEY cells that were stably transfected with

IQGAP3-shRNA and the corresponding NC were used for the

in vivo experiments. For in vivo experiments, eight

female athymic BALB-c nude mice (age, 5 weeks; weight, 20–30 g)

were purchased from Nanjing Biochemical Research Institute and

housed in a standard pathogen-free condition in individually

ventilated cages with HEPA filters at the ambient temperature of

30–31°C and humidity of 50–60% with 12 h light/dark cycle, and

adequate access to food and water. For tumor formation assays,

1×107 cells (knockdown or control), resuspended in 200

µl PBS were subcutaneously injected into either side of the

axilla.

For metastasis assays, 1×107 cells were

intraperitoneally injected individually in the experimental and

control groups. After 2–3 weeks, bioluminescence images were

captured on an In-vivo imaging system (Kodak 2000 Imager).

The mice were euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg

sodium phenobarbital and the tumors were excised, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 48 h, paraffin-embedded

and sectioned into 5-µm slices for hematoxylin and eosin staining.

The tissue slides were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min and eosin

for 10 min at room temperature and observed under a light

microscope (magnification, ×4).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc.)

was used to analyze data. A χ2 test was used to analyze

the differences in clinical characteristics. Survival analysis was

performed using Kaplan-Meier analysis and a log-rank test. An

unpaired Student's t-test and a one-way ANOVA were used to

determine the statistically significant differences between

different groups. Fisher's least significant difference was used

for the post-hoc test following ANOVA. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

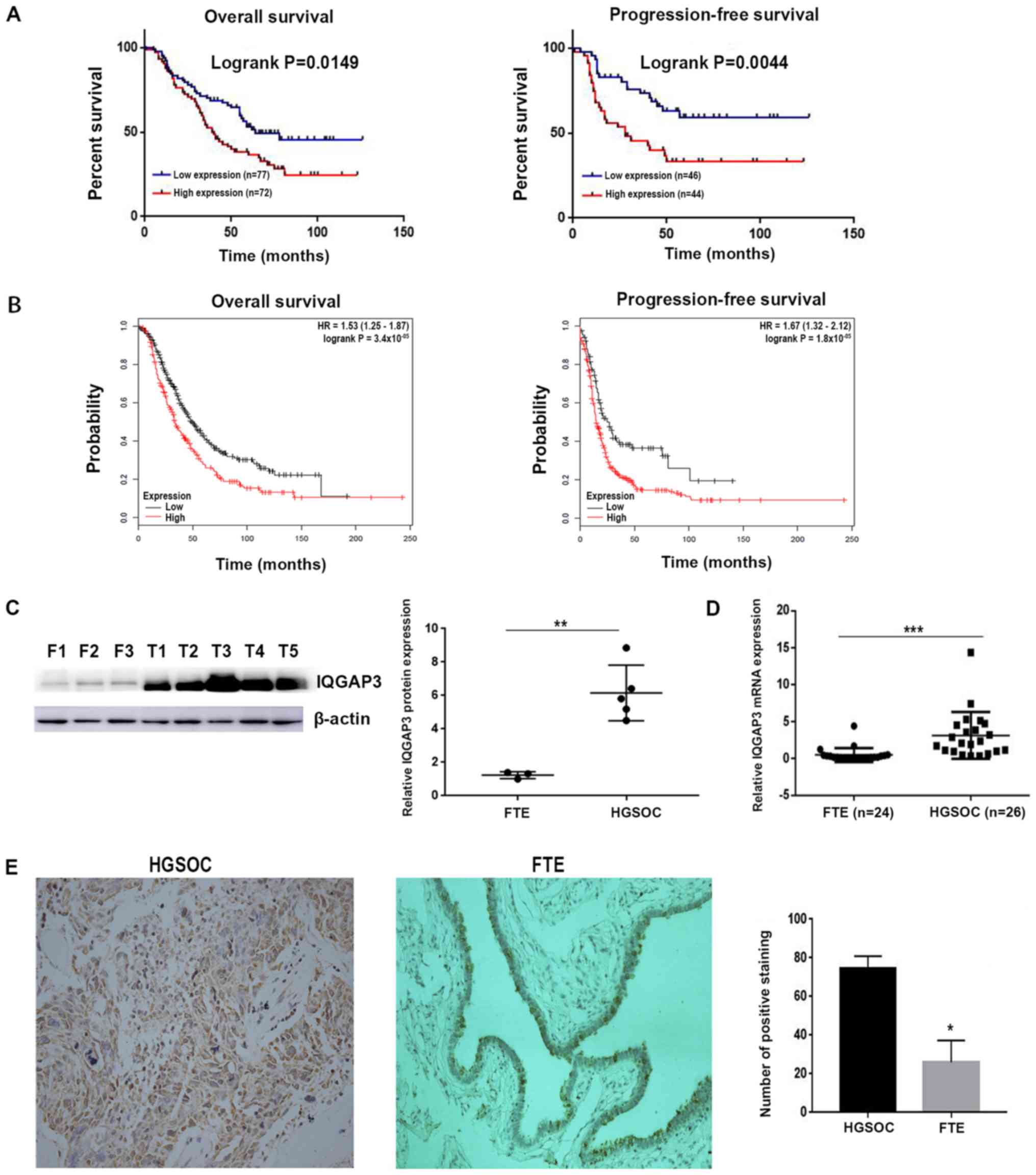

IQGAP3 expression is upregulated in

HGSOC

The mRNA and protein expression levels of

IQGAP3 in healthy fallopian tube and HGSOC tissues were

determined using RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. The

mRNA expression level of IQGAP3 was significantly higher in

HGSOC tissues compared with the control samples (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, IQGAP3 protein

expression was significantly upregulated in HGSOC tissues compared

with the fallopian tubal samples (Fig.

1C).

Upregulated expression of IQGAP3 is

associated with a less favorable prognosis

To examine whether upregulated expression of

IQGAP3 was associated with clinical prognosis, IHC staining

was performed on 149 HGSOC samples (Fig.

1E). Most positive staining was observed in the cytoplasm and

at the cell membrane. Moreover, a high expression of IQGAP3

was observed in 53.02% (79/149) of tissues. Subsequently, the

relationship between IQGAP3 and clinicopathological

characteristics were assessed (Table

I). The patients with a lower expression of IQGAP3 had

longer survival times compared with those with higher IQGAP3

expression levels. A log-rank test demonstrated that the

upregulated expression of IQGAP3 was significantly

associated with overall survival (P=0.0149), as well as

progression-free survival (P=0.0044; Fig. 1A).

| Table I.Association between IQGAP3 expression

and clinicopathologic characteristics. |

Table I.

Association between IQGAP3 expression

and clinicopathologic characteristics.

| Clinicopathologic

characteristics | High

expression | Low expression | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.2089 |

|

<55 | 42 | 30 |

|

|

≥55 | 37 | 40 |

|

| FIGO stage |

|

| 0.4367 |

| I +

II | 21 | 15 |

|

| III +

IV | 57 | 55 |

|

| CA125, U/ml |

|

| 0.0147a |

|

<600 | 20 | 38 |

|

|

≥600 | 50 | 41 |

|

| Ascites, ml |

|

| 0.3255 |

|

Yes | 59 | 58 |

|

| No | 13 | 19 |

|

| Peritoneal

metastasis |

|

| 0.0007b |

|

Yes | 33 | 20 |

|

| No | 32 | 64 |

|

| Lymph node

metastasis |

|

| 0.1703 |

|

Positive | 12 | 10 |

|

|

Negative | 23 | 38 |

|

| Recurrence |

|

| 0.0065b |

|

Yes | 56 | 41 |

|

| No | 8 | 20 |

|

Survival analysis performed on GEO cohorts using

Kaplan-Meier Plotter, showed a significant association between

IQGAP3 expression and both overall and progression-free

survival (Fig. 1B). In addition,

further analysis indicated that the expression of IQGAP3 was

associated with several other clinicopathological parameters,

including recurrence of the disease (P=0.0065), CA125 levels

(P=0.0147) and peritoneal metastasis (P=0.0007; Table I).

Downregulation of IQGAP3 reduces

proliferation and colony formation of HGSOC ovarian cancer cells,

and attenuates tumorigenicity in a xenograft model

Downregulation of IQGAP3 resulted in the

reduced proliferation of ovarian cancer cells in vitro.

Moreover, two siRNAs, si-IQGAP3−1 and si-IQGAP3−2,

were used to silence IQGAP3 in A2780 and HEY cells. MTT

assays results identified a significant suppression of the

proliferative capacity in the two cell lines following transfection

with the siRNAs compared with the NCs (Fig. 2A).

These findings were further assessed in the in

vivo experiments, where xenografts of BALB-c nude mice were

established with injection of HEY cells stably transfected with

sh-IQGAP3 or NC (Fig. 2C).

After 3 weeks, the mice were euthanized, imaged on a

bioluminescence imaging system, and the tumors were excised and

weighed. It was found that there was a significant decrease in

tumor size and tumor weight in the sh-IQGAP3 group compared

with the NC group (Fig. 2D and E),

supporting the in vitro results. Therefore, the results

demonstrated the contribution of IQGAP3 to tumor

proliferation.

Knockdown of IQGAP3 also significantly

reduced colony formation in both A2780 and HEY cell lines (Fig. 2B).

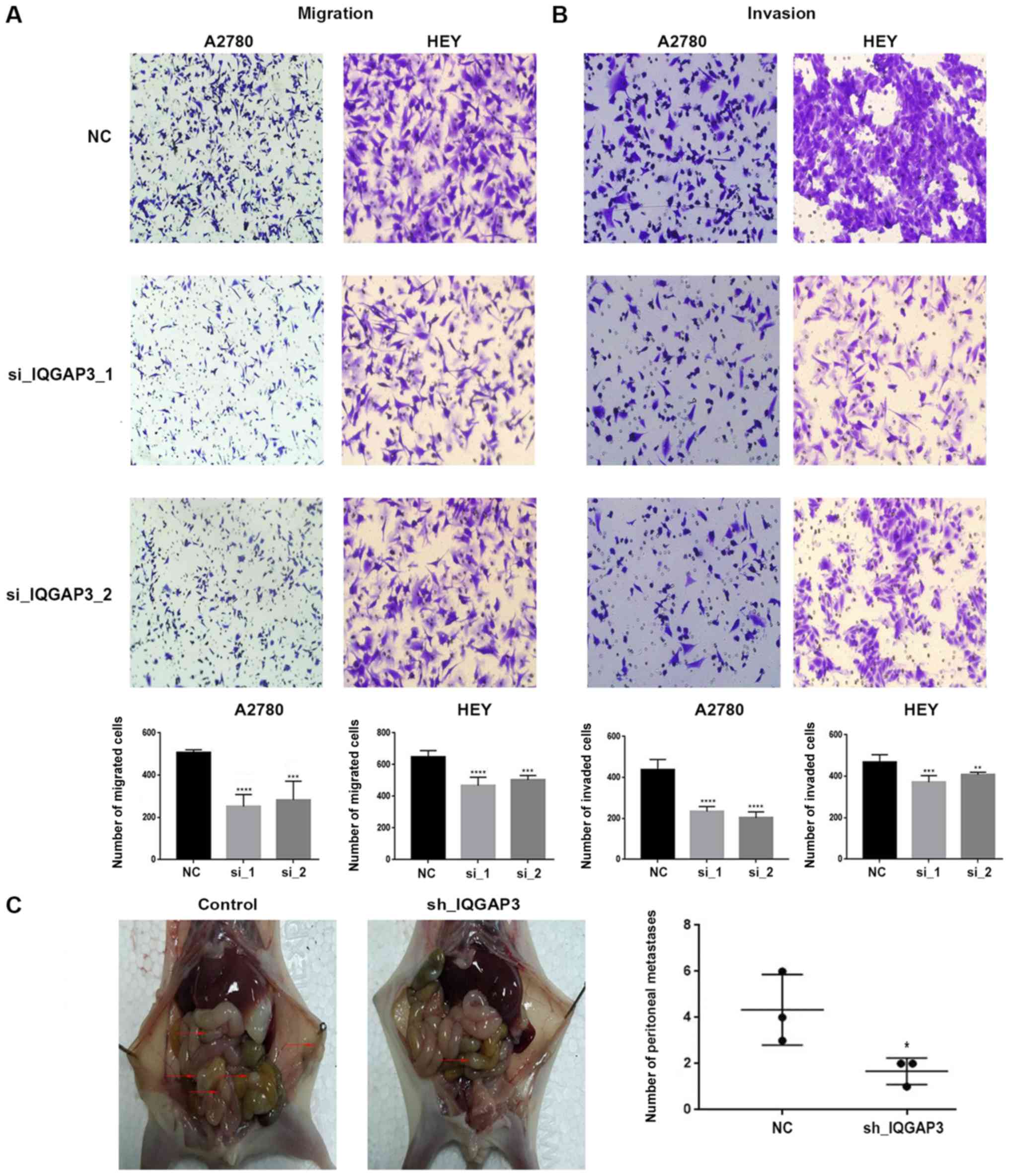

IQGAP3 increases migration and

invasion of ovarian cancer cells via epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition (EMT)

Transwell assays were used to examine the role of

IQGAP3 on migration and invasion in vitro. A2780 and

HEY cells both had significantly decreased migratory and invasive

capacities when IQGAP3 was knocked down compared with the

respective NC (Fig. 3A and B).

Furthermore, the underlying mechanism contributing

to this increase in tumorigenic features was determined by

analyzing EMT-related factors. Knockdown of IQGAP3 had an

effect on the expression of several EMT markers (Fig. 4). Silencing of IQGAP3 resulted

in downregulation of mesenchymal markers, including ZEB-1,

Vimentin, N-CAD and Snail, while the expression of the

epithelial marker E-CAD was upregulated. Thus, it was suggested

that IQGAP3 induced the migration and invasion of ovarian

cancer cells via induction of EMT.

| Figure 4.Western blot analysis revealed the

changes in protein expression of several proteins following

IQGAP3 knockdown using two siRNAs. Both A2780 and HEY cells

had an altered protein expression following the knockdown. The

alteration in the protein expression included EMT-related proteins

(E-CAD, N-CAD, ZEB-1, Vimentin and Snail),

apoptosis-related proteins (Caspase-3, Caspase-9, Bcl2 and

Bax), proteins associated with DNA damage and

chemoresistance (Rad51, p-ATM, ATM, CHK2 and

Pgp), and proteins involved in the regulation and mechanism

of the effect of IQGAP3 (CDC42, PI3K, p-AKT,

AKT, p-mTOR and mTOR). β-actin was used as

the internal control. IQGAP3, IQ motif containing GTPase

Activating Protein 3; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition;

p-, phosphorylated; E-CAD, E-cadherin; N-CAD, N-cadherin;

Pgp, phosphoglycolate phosphatase; Rad51, RAD51

recombinase; CHK2, checkpoint kinase 2; NC, negative

control; si, small interfering RNA; ZEB-1, zinc finger E-Box

binding homeobox 1. |

IQGAP3 reduces tumor metastasis in

vivo

To evaluate the role of IQGAP3 on metastasis

of ovarian cancer in vivo, female nude mice were injected

intraperitoneally with sh-IQGAP3-HEY cells or their

corresponding NCs. Then, 3 weeks after injection, the mice were

euthanized and the peritoneal cavities were examined for

metastases. Consistent with the in vitro experimental

results, mice injected with IQGAP3-silenced cells exhibited

significantly lower numbers of metastatic nodules compared with the

respective NC group (P<0.05; Fig.

3C). Bioluminescence imaging also identified larger metastatic

foci in the control group compared with the knockdown group

(Fig. 2E).

The excised metastatic nodules were fixed with

formalin and paraffin embedded and 4-µm thick slices were

sectioned. Subsequently, the slides were stained using hematoxylin

and eosin staining (Fig. S1).

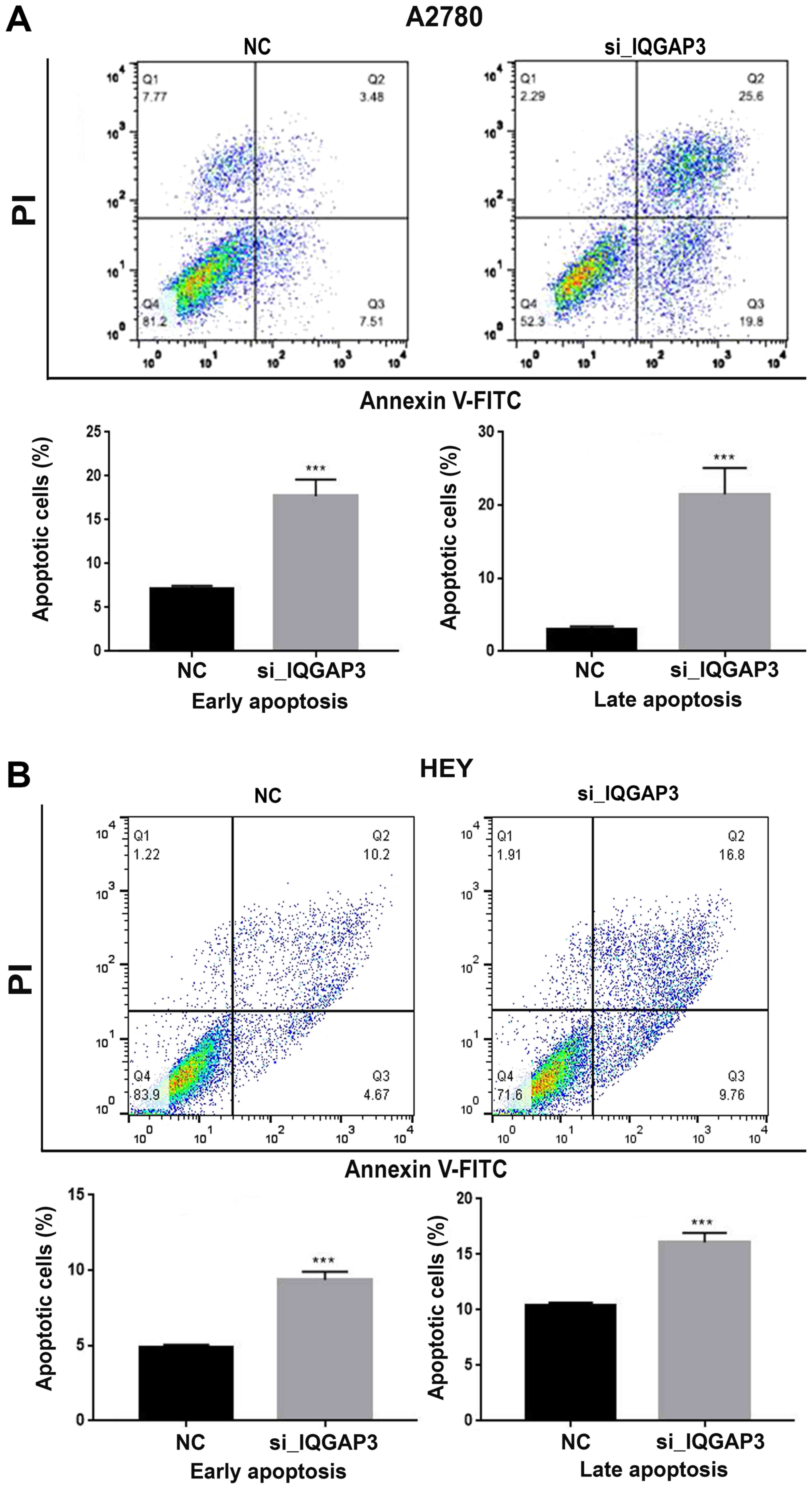

IQGAP3 knockdown promotes apoptosis in

ovarian cancer cells

To assess the effects of IQGAP3 knockdown on

apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells, Annexin V-FITC/PI dual staining

was performed following transfection with si-IQGAP3 or NC.

Both A2780 and HEY cells exhibited significantly increased

apoptosis following knockdown of IQGAP3 compared with the

respective NC group (Fig. 5A and B).

These results were further validated by the increased expression of

the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax, Caspase 3 and Caspase 9, and

decreased expression of Bcl-2 following IQGAP3

knockdown (Fig. 4).

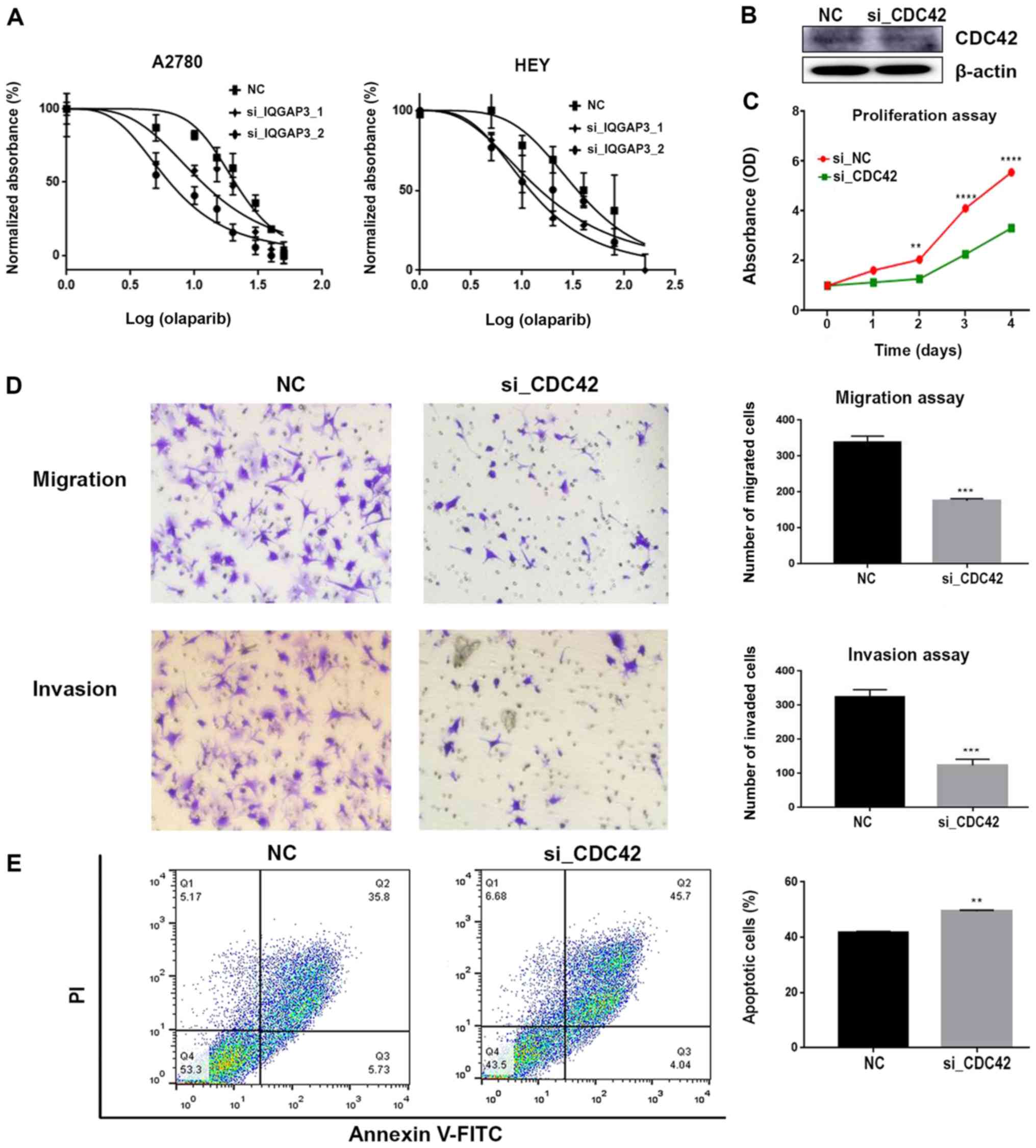

IQGAP3 knockdown increases sensitivity

to chemotherapy with PARPi

The si-IQGAP3 transfected A2780 and HEY cells

were exposed to various concentrations of olaparib (5, 10, 20, 40

or 80 µmol/ml) for 36–72 h, after which, the cell viability was

assessed using an MTT assay. Cells transfected with

si-IQGAP3 exhibited increased sensitivity to olaparib

compared with the respective control group (Fig. 6A). Western blotting results

identified the downregulation of the expression levels of

Rad51, p-ATM (normalized to total ATM) and

CHK2 when IQGAP3 expression was knocked down

(Fig. 4). Thus, knockdown of

IQGAP3 may have sensitized cells to olaparib by

downregulating key factors involved in the DNA damage response.

Phosphoglycolate Phosphatase (Pgp) is a

multidrug resistance protein that is localized in the cell membrane

and is responsible for extruding several xenobiotics (including

chemotherapeutic agents) outside the cells, rendering the cells

chemoresistant (45). IQGAP3

knockdown reduced the expression of Pgp, which in turn

attenuated chemoresistance (Fig. 4).

Therefore, it was speculated that this effect may underlie the

enhanced sensitivity of cells towards olaparib following

IQGAP3 knockdown.

IQGAP3 exerts its function via the

regulation of CDC42

It has been reported that IQGAP3 is an

effector of CDC42 (28). Xu

et al (35) also revealed

that IQGAP3 may exert its oncogenic function in pancreatic

cancer via the regulation of CDC42. To determine whether

IQGAP3 was associated with CDC42 in ovarian cancer,

the protein expression levels of CDC42 in ovarian cancer

cells were assessed by knocking down IQGAP3 expression. It

was identified that knockdown of IQGAP3 decreased the

expression of CDC42 (Fig.

4).

Therefore, the effects of CDC42 on the cancer

cells were assessed. Knockdown of CDC42 expression (Fig. 6B) resulted in a significant decrease

in the proliferative potential of HEY cells (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, migration and

invasion were inhibited, while apoptosis was enhanced following

CDC42 knockdown (Fig. 6D and

E). Collectively, these results suggest that IQGAP3 may

exert its effects via the regulation of CDC42.

Discussion

The principle dilemma when dealing with ovarian

cancer is the rate of distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis

and its resistance to chemotherapy, which frequently results in

negative consequences (1,46–48).

Thus, there is an unmet need for an improved understanding of the

molecular mechanisms involved in the proliferation, metastasis and

chemoresistance of ovarian cancer.

Out of the three primary members of the

IQGAP family, IQGAP1 has been reported to be an

oncogene, and IQGAP2 a tumor suppressor (24–26,49).

Furthermore, IQGAP3 is a scaffolding protein, which

interacts with various structural proteins that influence the

cytoskeletal dynamics and intracellular signaling (28). IQGAP3 has also previously been

implicated in the proliferation of epithelial cells (27). Moreover, previous studies have

revealed the role of IQGAP3 in the proliferation and

metastasis of lung, gastric, breast, pancreatic cancer, and

colorectal cancer as well as hepatocellular carcinoma (29–35).

Therefore, the role of IQGAP3 is crucial in the malignant

transformation of several types of cancer. Yang et al

(29) also reported that

IQGAP3 promotes the metastasis of lung cancer cells by

activating the epidermal growth factor receptor/ERK signaling

pathway. In addition, Yang et al (29) used bioinformatics analysis to show

that IQGAP3 is upregulated in several malignancies,

including ovarian cancer. Furthermore, Wu et al (50) reported there were alterations in the

genes regulating cytoskeleton remodeling in metastatic lung

adenocarcinoma and that IQGAP3 was a marker of a less

favorable prognosis.

The present results indicated that IQGAP3

was upregulated in ovarian cancer, and this enhanced expression

resulted in increased proliferative and metastatic capacities in

vitro and in vivo. Upon silencing IQGAP3, the

aggressive nature of ovarian cancer cells was significantly

abrogated. Thus, IQGAP3 may be a putative oncogene in HGSOC.

Moreover, the upregulated expression of IQGAP3 was

associated with a shorter overall and progression-free survival,

cancer recurrence and CA125 expression. Kaplan-Meier survival

analysis on data obtained from the online GEO database also

demonstrated that patients with an upregulated expression of

IQGAP3 exhibited reduced survival rates, further validating

the in vitro and in vivo results. However, whether

IQGAP3 is an independent poor prognostic factor of HGSOC is

yet to be determined.

A number of in vitro and in vivo

experiments were designed to establish the oncogenic potential of

IQGAP3 in HGSOC. IQGAP3 expression was significantly

upregulated in HGSOC compared with the healthy control. Cell

proliferation and tumorigenesis assays in nude mice demonstrated

the decreased proliferative capacity of ovarian cancer cells when

IQGAP3 was knocked down in vitro and in

vivo.

Metastasis is a culmination of cancer cells gaining

migratory and invasive abilities (51). Furthermore, distant metastasis at the

time of diagnosis is one of the major obstacles negatively

impacting the prognosis of ovarian cancer (52). The molecular mechanisms of metastasis

in ovarian cancer are yet to be fully elucidated; however, EMT has

been considered to be a potential contributing factor (52–54).

The present results suggested that IQGAP3

serves a substantial role in migration and invasion of ovarian

cancer, and knocking down IQGAP3 reduced the metastatic

potential. These findings were also observed in vivo, where

fewer metastatic foci formed in the mice injected with

IQGAP3-silenced cells compared with the control group.

EMT is initiated by several EMT-inducing

transcription factors (53–58). In the present study, it was found

that several of the EMT-inducing factors were affected by

alterations in the expression of IQGAP3, which suggests a

pivotal role of IQGAP3 in the induction of EMT in ovarian

cancer.

Several studies have reported that the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a crucial pathway by which

cancer cells exhibit increased proliferative and metastatic

potential (59–64). This signaling pathway is involved in

several fundamental processes in ovarian cancer, such as cell

proliferation, survival, autophagy, transcription regulation and

angiogenesis (63,64). Therefore, to determine the mechanism

underlying the effects of IQGAP3 in ovarian cancer, the

effects of altering IQGAP3 gene expression of the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway were determined. Western blot analysis

revealed a significant downregulation in the expression levels of

PI3K, p-AKT and p-mTOR when IQGAP3

expression was knocked down. Thus, these results suggested that

IQGAP3 may promote tumor progression and metastasis via the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

Previous studies have shown that increased

apoptosis may underlie decreased tumor growth, chemoresistance and

metastasis in several types of cancer (65,66). It

has also been reported that IQGAP3 in certain types of

cancer is closely associated with apoptosis (35). In the present study, it was

demonstrated that the apoptotic potential of cells was increased

when IQGAP3 expression was knocked down, and this may

underlie the effects of IQGAP3 on tumor growth.

CDC42 is a member of the Rho family of

GTPases, and is ubiquitously expressed (23). Moreover, CDC42 participates in

the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics, cellular proliferation,

motility, polarity and cytokinesis (67). Wang et al (28) also identified a direct interaction

between IQGAP3 with CDC42, and revealed IQGAP3

is an indispensable effector of CDC42-mediated cell

proliferation. Furthermore, Xu et al (35) hypothesized that IQGAP3 may

serve as an oncogene in pancreatic cancer by regulating the

CDC42 signaling pathway. Morgan et al (68) reported there was an interaction

between IQGAP3 and CDC42 using immunoprecipitation

assays. The results of the present study also demonstrated that

knocking down IQGAP3 expression resulted in the

downregulation of CDC42 expression. Therefore, the role of

CDC42 in ovarian cancer cells was further investigated. It

was found that knockdown of CDC42 resulted in a significant

decrease in proliferation, migration and invasion, and increased

apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Thus, it was speculated that

IQGAP3 may exert its function via modulation of

CDC42, but further studies are required to verify this

hypothesis.

PARP serves a key role in the DNA damage

response of the cell (10,11,13). The

PARP inhibitor olaparib has been recently approved by the

FDA for the treatment of patients with ovarian cancer who harbor

BRCA1/2 mutations (15).

Moreover, BRCA1/2 mutations are responsible for 18–40% of

lifetime risk ovarian cancer cases in women, and 5–15% of all

diagnosed cases harbor one of these mutations (69). Thus, the introduction of PARPi, such

as olaparib, may improve the prognostic prospects of patients.

However, this drug is not effective for all HGSOC cases (70). IQGAP3 is associated with

olaparib drug sensitivity, and knockdown of IQGAP3 in the

present study resulted in increased efficacy of olaparib,

suggesting that the effectiveness of the treatment may be dependent

upon specific clinical aspects. Additionally, the expression

profiles of proteins involved in DNA damage response of cell,

including ATM and CHK, were assessed. In the present study, there

was a significant decrease in the expression levels of these

proteins following IQGAP3 knockdown. Furthermore, similar

effects were observed in Rad51, which possesses a crucial role in

the homologous recombination repair of DNA (10). Therefore, it was hypothesized that

downregulation of DNA repair factors may result in defective DNA

repair in cells, thus increasing the sensitivity to PARPi.

However, further investigations focusing on the

mechanistic role of IQGAP3 in proliferation and metastasis

of ovarian cancer are required before IQGAP3 may be

considered a diagnostic and prognostic marker, and as a potential

therapeutic target for ovarian cancer. To the best of our

knowledge, the present study was the first to report the role of

IQGAP3 in the progression of HGSOC.

In conclusion, IQGAP3 exhibited oncogenic

features in HGSOC. In addition, the expression of IQGAP3 was

upregulated in HGSOC, and its expression was associated with a poor

outcome in patients. However, more studies are required to further

validate IQGAP3 as a prognostic marker and a therapeutic

target for ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the

contribution of Dr Kun Song from the Department of OB/GYN and Dr

Ning Yang from the Department of Pathology at Qilu Hospital of

Shandong University (Ji'nan, China), and Dr Shi Yan, Dr Rongrong Li

and Dr Cunzong Yuan from the Key Laboratory of Gynecologic Oncology

of Shandong (Ji'nan, China), who contributed greatly to the

completion of this manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81874107 and

81572554).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study

are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

SD, QZ and BK contributed to the conceptualization

of the study. SD drafted the manuscript. SD, CQ, CS, ZZ and HW

contributed to data acquisition, carried out the data analysis and

revised the manuscript. QZ and BK were involved in analyzing the

critical intellectual content and gave the final approval of the

version to be published. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Signed consents were collected from all the

patients and the study was approved by Ethics Committee of Qilu

hospital of Shandong University. Approval of Shandong University

Animal Care and Use Committee was acquired for all the animal

experiments.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 69:7–34. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cancer Stat Facts: Ovarian Cancer. 2019.

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ozols RF: Systemic therapy for ovarian

cancer: Current status and new treatments. Semin Oncol. 33 (Suppl

6):S3–S11. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Karnezis AN, Cho KR, Gilks CB, Pearce CL

and Huntsman DG: The disparate origins of ovarian cancers:

Pathogenesis and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Cancer. 17:65–74.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cho KR and Shih IeM: Ovarian cancer. Annu

Rev Pathol. 4:287–313. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kurman RJ and Shih IeM: The origin and

pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: A proposed unifying

theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 34:433–443. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bast RC Jr, Hennessy B and Mills GB: The

biology of ovarian cancer: New opportunities for translation. Nat

Rev Cancer. 9:415–428. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Haiba M,

Boice CR, Kurman RJ and Ronnett BM: The histologic type and stage

distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin.

Int J Gynecol Pathol. 23:41–44. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Köbel M,

Harris HR, Berchuck A, Rossing MA and Doherty JA: Invasive

epithelial ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 111:60–68. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pilié PG, Tang C, Mills GB and Yap TA:

State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response

in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 16:81–104. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

AlHilli MM, Becker MA, Weroha SJ, Flatten

KS, Hurley RM, Harrell MI, Oberg AL, Maurer MJ, Hawthorne KM, Hou

X, et al: In vivo anti-tumor activity of the PARP inhibitor

niraparib in homologous recombination deficient and proficient

ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 143:379–388. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

McGuire WP III and Markman M: Primary

ovarian cancer chemotherapy: Current standards of care. Br J

Cancer. 89 (Suppl 3):S3–S8. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pokhriyal R, Hariprasad R, Kumar L and

Hariprasad G: Chemotherapy resistance in advanced ovarian cancer

patients. Biomark Cancer. 11:1179299X198608152019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG,

Oaknin A, Friedlander M, Lisyanskaya A, Floquet A, Leary A, Sonke

GS, et al: Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed

advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 379:2495–2505. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kim G, Ison G, McKee AE, Zhang H, Tang S,

Gwise T, Sridhara R, Lee E, Tzou A, Philip R, et al: FDA approval

summary: Olaparib monotherapy in patients with deleterious germline

BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated with three or more

lines of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 21:4257–4261. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Briggs MW and Sacks DB: IQGAP proteins are

integral components of cytoskeletal regulation. EMBO Rep.

4:571–574. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Weissbach L, Settleman J, Kalady MF,

Snijders AJ, Murthy AE, Yan YX and Bernards A: Identification of a

human rasGAP-related protein containing calmodulin-binding motifs.

J Biol Chem. 269:20517–20521. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hedman AC, Smith JM and Sacks DB: The

biology of IQGAP proteins: Beyond the cytoskeleton. EMBO Rep.

16:427–446. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Swart-Mataraza JM, Li Z and Sacks DB:

IQGAP1 is a component of Cdc42 signaling to the cytoskeleton. J

Biol Chem. 277:24753–24763. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sahai E and Marshall CJ: RHO-GTPases and

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2:133–142. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tang Y, Olufemi L, Wang MT and Nie D: Role

of Rho GTPases in breast cancer. Front Biosci. 13:759–776. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Erickson JW and Cerione RA: Multiple roles

for Cdc42 in cell regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 13:153–157.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Arias-Romero LE and Chernoff J: Targeting

Cdc42 in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 17:1263–1273. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Johnson M, Sharma M and Henderson BR:

IQGAP1 regulation and roles in cancer. Cell Signal. 21:1471–1478.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mataraza JM, Briggs MW, Li Z, Entwistle A,

Ridley AJ and Sacks DB: IQGAP1 promotes cell motility and invasion.

J Biol Chem. 278:41237–41245. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Schmidt VA, Chiariello CS, Capilla E,

Miller F and Bahou WF: Development of hepatocellular carcinoma in

Iqgap2-deficient mice is IQGAP1 dependent. Mol Cell Biol.

28:1489–1502. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nojima H, Adachi M, Matsui T, Okawa K and

Tsukita S and Tsukita S: IQGAP3 regulates cell proliferation

through the Ras/ERK signalling cascade. Nat Cell Biol. 10:971–978.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang S, Watanabe T, Noritake J, Fukata M,

Yoshimura T, Itoh N, Harada T, Nakagawa M, Matsuura Y, Arimura N

and Kaibuchi K: IQGAP3, a novel effector of Rac1 and Cdc42,

regulates neurite outgrowth. J Cell Sci. 120:567–577. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yang Y, Zhao W, Xu QW, Wang XS, Zhang Y

and Zhang J: IQGAP3 promotes EGFR-ERK signaling and the growth and

metastasis of lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 9:e975782014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hu G, Xu Y, Chen W, Wang J, Zhao C and

Wang M: RNA Interference of IQ motif containing GTPase-activating

protein 3 (IQGAP3) inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in

breast carcinoma cells. Oncol Res. 24:455–461. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Shi Y, Qin N, Zhou Q, Chen Y, Huang S,

Chen B, Shen G and Jia H: Role of IQGAP3 in metastasis and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Transl Med. 15:1762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cao H, Wang Q, Gao Z, Xu X, Lu Q and Wu Y:

Clinical value of detecting IQGAP3, B7-H4 and cyclooxygenase-2 in

the diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of colorectal cancer.

Cancer Cell Int. 19:1632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wu J, Chen Z, Cao H, Yu Z, Feng J, Wang K,

Lu Q and Wu Y: High expression of IQGAP3 indicates poor prognosis

in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Biol Markers. 34:348–355.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yasui W, Sentani K, Sakamoto N, Anami K,

Naito Y and Oue N: Molecular pathology of gastric cancer: Research

and practice. Pathol Res Pract. 207:608–612. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xu W, Xu B, Yao Y, Yu X, Cao H, Zhang J,

Liu J and Sheng H: Overexpression and biological function of IQGAP3

in human pancreatic cancer. Am J Transl Res. 8:5421–5432.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Javadi S, Ganeshan DM, Qayyum A, Iyer RB

and Bhosale P: Ovarian cancer, the revised FIGO staging system, and

the role of imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 206:1351–1360. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Birrer MJ, Johnson ME, Hao K, Wong KK,

Park DC, Bell A, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS and Mok SC: Whole genome

oligonucleotide-based array comparative genomic hybridization

analysis identified fibroblast growth factor 1 as a prognostic

marker for advanced-stage serous ovarian adenocarcinomas. J Clin

Oncol. 25:2281–2287. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Mateescu B, Batista L, Cardon M, Gruosso

T, de Feraudy Y, Mariani O, Nicolas A, Meyniel JP, Cottu P,

Sastre-Garau X and Mechta-Grigoriou F: miR-141 and miR-200a act on

ovarian tumorigenesis by controlling oxidative stress response. Nat

Med. 17:1627–1635. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ferriss JS, Kim Y, Duska L, Birrer M,

Levine DA, Moskaluk C, Theodorescu D and Lee JK: Multi-gene

expression predictors of single drug responses to adjuvant

chemotherapy in ovarian carcinoma: Predicting platinum resistance.

PLoS One. 7:e305502012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lisowska KM, Olbryt M, Dudaladava V,

Pamuła-Piłat J, Kujawa K, Grzybowska E, Jarzab M, Student S,

Rzepecka IK, Jarzab B and Kupryjańczyk J: Gene expression analysis

in ovarian cancer-faults and hints from DNA microarray study. Front

Oncol. 4:62014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tothill RW, Tinker AV, George J, Brown R,

Fox SB, Lade S, Johnson DS, Trivett MK, Etemadmoghadam D, Locandro

B, et al: Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid

ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res.

14:5198–5208. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Uehara Y, Oda K, Ikeda Y, Koso T, Tsuji S,

Yamamoto S, Asada K, Sone K, Kurikawa R, Makii C, et al: Integrated

copy number and expression analysis identifies profiles of

Whole-arm chromosomal alterations and subgroups with favorable

outcome in ovarian clear cell carcinomas. PLoS One.

10:e01280662015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gyorffy B, Lánczky A and Szállási Z:

Implementing an online tool for genome-wide validation of

survival-associated biomarkers in ovarian-cancer using microarray

data from 1287 patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 19:197–208. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pokharel D, Roseblade A, Oenarto V, Lu JF

and Bebawy M: Proteins regulating the intercellular transfer and

function of P-glycoprotein in multidrug-resistant cancer.

Ecancermedicalscience. 11:7682017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Naora H and Montell DJ: Ovarian cancer

metastasis: Integrating insights from disparate model organisms.

Nat Rev Cancer. 5:355–366. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Campos SM and Ghosh S: A current review of

targeted therapeutics for ovarian cancer. J Oncol. 149362:2010.

|

|

48

|

Hogberg T: Chemotherapy: Current drugs

still have potential in advanced ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 7:191–193. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

White CD, Khurana H, Gnatenko DV, Li Z,

Odze RD, Sacks DB and Schmidt VA: IQGAP1 and IQGAP2 are

reciprocally altered in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC

Gastroenterol. 10:1252010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wu K, Zhang X, Li F, Xiao D, Hou Y, Zhu S,

Liu D, Ye X, Ye M, Yang J, et al: Frequent alterations in

cytoskeleton remodelling genes in primary and metastatic lung

adenocarcinomas. Nat Commun. 6:101312015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Guan X: Cancer metastases: Challenges and

opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B. 5:402–418. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Huang RY, Chung VY and Thiery JP:

Targeting pathways contributing to epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) in epithelial ovarian cancer. Curr Drug Targets.

13:1649–1653. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Berx G, Raspe E, Christofori G, Thiery JP

and Sleeman JP: Pre-EMTing metastasis? Recapitulation of

morphogenetic processes in cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 24:587–597.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lamouille S, Xu J and Derynck R: Molecular

mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 15:178–196. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Thiery JP and Sleeman JP: Complex networks

orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 7:131–142. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Barrallo-Gimeno A and Nieto MA: The Snail

genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: Implications in

development and cancer. Development. 132:3151–3161. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Hugo H, Ackland ML, Blick T, Lawrence MG,

Clements JA, Williams ED and Thompson EW: Epithelial-mesenchymal

and mesenchymal-epithelial transitions in carcinoma progression. J

Cell Physiol. 213:374–383. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Peinado H, Olmeda D and Cano A: Snail, Zeb

and bHLH factors in tumour progression: An alliance against the

epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 7:415–428. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Cantley LC: The phosphoinositide 3-kinase

pathway. Science. 296:1655–1657. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Fresno Vara JA, Casado E, de Castro J,

Cejas P, Belda-Iniesta C and Gonzalez-Baron M: PI3K/Akt signalling

pathway and cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 30:193–204. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Willems L, Tamburini J, Chapuis N, Lacombe

C, Mayeux P and Bouscary D: PI3K and mTOR signaling pathways in

cancer: New data on targeted therapies. Curr Oncol Rep. 14:129–138.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

McAuliffe P, Meric-Bernstam F, Mills GB

and Gonzalez-Angulo A: Deciphering the role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR

pathway in breast cancer biology and pathogenesis. Clin Breast

Cancer. 10 (Suppl 3):S59–S65. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Gasparri ML, Bardhi E, Ruscito I, Papadia

A, Farooqi AA, Marchetti C, Bogani G, Ceccacci I, Mueller MD and

Benedetti Panici P: PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer

treatment: Are we on the right track? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd.

77:1095–1103. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Mabuchi S, Kuroda H, Takahashi R and

Sasano T: The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target in

ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 137:173–179. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wong RS: Apoptosis in cancer: From

pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 30:872011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Su Z, Yang Z, Xu Y, Chen Y and Yu Q:

Apoptosis, autophagy, necroptosis, and cancer metastasis. Mol

Cancer. 14:482015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Melendez J, Grogg M and Zheng Y: Signaling

role of Cdc42 in regulating mammalian physiology. J Biol Chem.

286:2375–2381. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Morgan CJ, Hedman AC, Li Z and Sacks DB:

Endogenous IQGAP1 and IQGAP3 do not functionally interact with Ras.

Sci Rep. 9:110572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ramus SJ and Gayther SA: The contribution

of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol. 3:138–150. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Jiang X, Li X, Li W, Bai H and Zhang Z:

PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Sensitivity prediction and

resistance mechanisms. J Cell Mol Med. 23:2303–2313. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|