Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer and the

major cause of cancer-associated mortalities among women worldwide

(1). A total of 2,088,849 new cases

and 626.679 mortalities were reported globally for BC in 2018

(2). It was also reported that the

5-year survival rate of patients with BC during 2007–2013 was 90%

in the USA. The standard treatment modalities for BC include

surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and hormone

therapy (3–5). Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

is the earliest stage of BC and refers to a heterogeneous group of

precursor lesions (6). Approximately

20–25% of patients with BC are diagnosed with DCIS (7). While not all DCIS cases progress to

invasive BC, DCIS is usually excised as its potential for invasion

remains difficult to predict (8).

Previous studies have focused on analyzing the

molecular differences between DCIS and invasive BC and the

potential progression mechanisms (9–12). The

upregulation of erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2) is

considered to be an early step in the progression of DCIS (13,14).

Shah et al (13) revealed

that the downregulation of Rap1Gap, a GTPase-activating protein,

promotes the progression of DCIS to invasive ductal carcinoma by

activating the extracellular signal-regulated

kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. In the

phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway alterations have also

been reported to be associated with the progression of DCIS

(14). Additionally, the

upregulation of cyclin D1, MYC proto-oncogene bHLH transcription

factor and ERBB2, have previously been observed in DCIS (15). The upregulation of matrix

metalloproteinase (MMPs), including MMP2, and downregulation of

cadherin 1 are frequently observed in the progression from DCIS to

invasive BC via the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (9,16).

Previous studies have revealed that certain biomarkers, including

the ki67 proliferation marker, the tumor protein p53 tumor

suppressor gene and the estrogen receptor, may serve as prognostic

predictors in DCIS (17,18). However, further investigation of the

molecular features and differences between DCIS and normal breast

tissues is required. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to

identify key genes involved in DCIS and to explore their prognostic

values by integrating bioinformatics tools.

Materials and methods

Gene expression level analysis of DCIS

and normal breast tissue samples

The gene expression profiles of 46 DCIS and three

normal breast tissues in the GSE59248 dataset (19) were downloaded from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). This dataset was

analyzed using the Agilent-028004 SurePrint G3 Human GE 8×60K

Microarray platform (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The online tool

GEO2R (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r) was subsequently used

to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between DCIS

and normal breast tissues using the Benjamini and Hochberg false

discovery rate (20). The cut-off

criteria for the selection of DEGs were an adjusted P<0.05 and a

|log2 fold-change|>2.

Functional enrichment analyses of the

DEGs

Gene Ontology (GO) (http://geneontology.org) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed to explore the

biological functions of the DEGs. GO functional analysis, which

includes biological processes, cellular components and molecular

functions, was performed using the Protein Analysis Through

Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) classification system

(16). KEGG pathways enrichment

analysis was performed using the Database for Annotation,

Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; version 6.8)

(https://david.ncifcrf.gov) (17). The criteria for significance were

P<0.05 and the number of enriched DEGs in pathways ≥5.

Construction of the protein-protein

interaction (PPI) network

To further explore the associations between the

identified DEGs, a PPI network was constructed using the Search

Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING)

database (https://string-db.org) (18) and visualized using Cytoscape software

(version 3.6.1) (21). In the PPI

network, the nodes and edges represent proteins and their

interactions, respectively. The genes in the PPI network with the

highest connectivity were considered hub genes. The potential hub

genes were screened from the entire PPI network using the cytoHubba

plug-in and the maximal clique centrality algorithm (22,23).

Survival analysis of hub genes with

the log-rank test

To evaluate the prognostic values of the identified

hub genes in patients with DCIS, an overall survival (OS) analysis

was carried out using the Kaplan-Meier plotter (https://kmplot.com/analysis/), which is a web-based

tool to assess the effect of 54,675 genes on survival in 21 cancer

types (24).

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp.) was used to

perform the statistical analysis. The data were presented with mean

± SD. The associations between the clinicopathological parameters

and hub gene expression were analyzed using the χ2 test.

When the sample size was <40, the Fisher's exact test was

applied. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. The α level was 0.05.

Results

DEGs between DCIS and normal tissue

samples

A total of 316 DEGs, including 32 upregulated and

284 downregulated genes, were identified in the GSE59248 dataset.

The GSE59248 dataset included the gene expression profiles of 46

DCIS and 3 normal breast tissue samples.

Functional enrichment analyses of the

DEGs

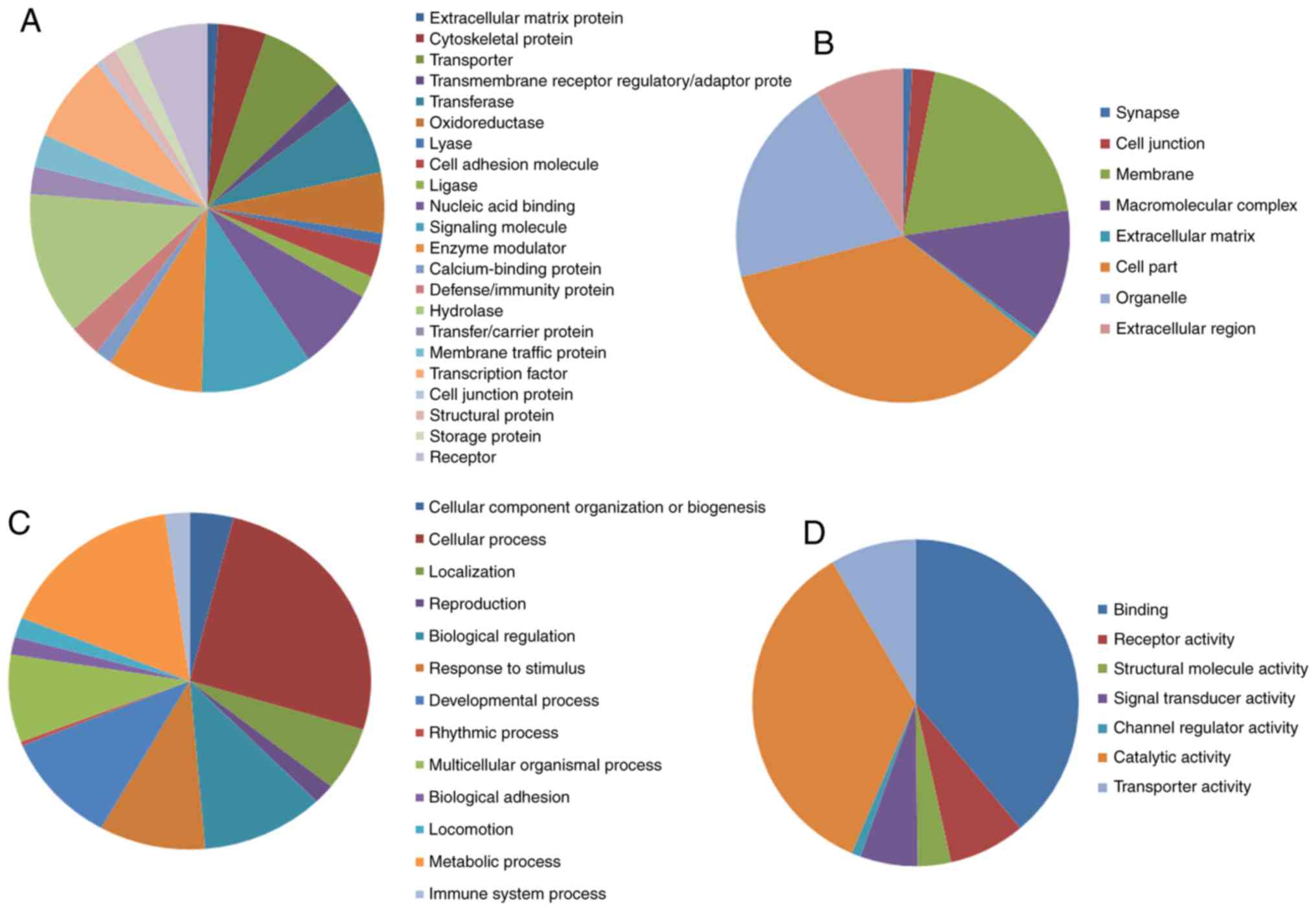

The analytical results of the PANTHER classification

system revealed that the identified DEGs could be classified into

22 protein categories, including signaling molecules, transporters,

hydrolases, enzyme modulators and transcription factors (Fig. 1A; Table

I). The GO analysis revealed that these DEGs were significantly

involved in cellular components such as ‘cell part’, ‘organelle’,

‘membranes’ and ‘macromolecular complex’ (Fig. 1B; Table

I). In terms of biological processes, the DEGs are mainly

associated with ‘metabolic process’, ‘cellular process’,

‘biological regulation’, ‘developmental process’ and ‘response to

stimulus’ (Fig. 1C; Table I). Regarding molecular functions, the

DEGs were mainly associated with ‘catalytic activity’, binding,

transporter activity and signal transducer activity (Fig. 1D; Table

I). The analysis of KEGG pathways using DAVID indicated that

the DEGs are mainly enriched in pathways such as ‘PPAR signaling

pathway’, ‘AMPK signaling pathway’, ‘regulation of lipolysis in

adipocytes’ and ‘glucagon signaling pathway’ (Fig. 2).

| Table I.Functional enrichment analyses of the

differentially expressed genes in ductal carcinoma in situ

using the Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships

classification system. The top eight items with its counting

percentage in each category were present. |

Table I.

Functional enrichment analyses of the

differentially expressed genes in ductal carcinoma in situ

using the Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships

classification system. The top eight items with its counting

percentage in each category were present.

| A, Protein

categories |

|---|

|

|---|

| Term | Percentage |

|---|

| Hydrolase | 12.60 |

| Signaling

molecule | 10.20 |

| Enzyme

modulator | 8.70 |

| Transcription

factor | 7.80 |

| Transporter | 7.80 |

| Nucleic acid

binding | 7.30 |

| Transferase | 6.80 |

| Receptor | 6.80 |

|

| B, Cellular

component |

|

| Term |

Percentage |

|

| Cell part | 35.50 |

| Organelle | 20.30 |

| Membrane | 19.50 |

| Macromolecular

complex | 12.60 |

| Extracellular

region | 8.70 |

| Cell junction | 2.20 |

| Synapse | 0.90 |

| Extracellular

matrix | 0.40 |

|

| C, Biological

process |

|

| Term |

Percentage |

|

| Cellular

process | 25.80 |

| Metabolic

process | 16.70 |

| Biological

regulation | 11.00 |

| Developmental

process | 10.60 |

| Response to

stimulus | 9.50 |

| Multicellular

organismal process | 8.40 |

| Localization | 6.10 |

| Cellular component

organization or biogenesis | 3.90 |

|

| D, Molecular

function |

|

| Term |

Percentage |

|

| Binding | 38.90 |

| Catalytic

activity | 35.10 |

| Transporter

activity | 8.50 |

| Receptor

activity | 7.60 |

| Signal transducer

activity | 5.70 |

| Structural molecule

activity | 3.30 |

| Channel regulator

activity | 0.90 |

PPI network and hub genes

In the present study, the STRING database was used

to construct a PPI network to visualize the protein-protein

interactions between the DEGs (Fig.

3). The network consisted of a total of 315 nodes and 474

edges. The local clustering coefficient of the PPI network was

0.374 and the average node degree was 3.01. The top eight hub genes

were identified from the PPI network using the cytoHubba plugin and

the maximal clique centrality algorithm. The hub genes were as

follows: Lipase E hormone sensitive type (LIPE), patatin-like

phospholipase domain-containing 2 (PNPLA2), adiponectin (ADIPOQ),

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARG), fatty

acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2

(DGAT2), lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and leptin (LEP; Fig. 4). The above mentioned hub genes were

downregulated in DCIS compared with normal breast tissue (Fig. 5).

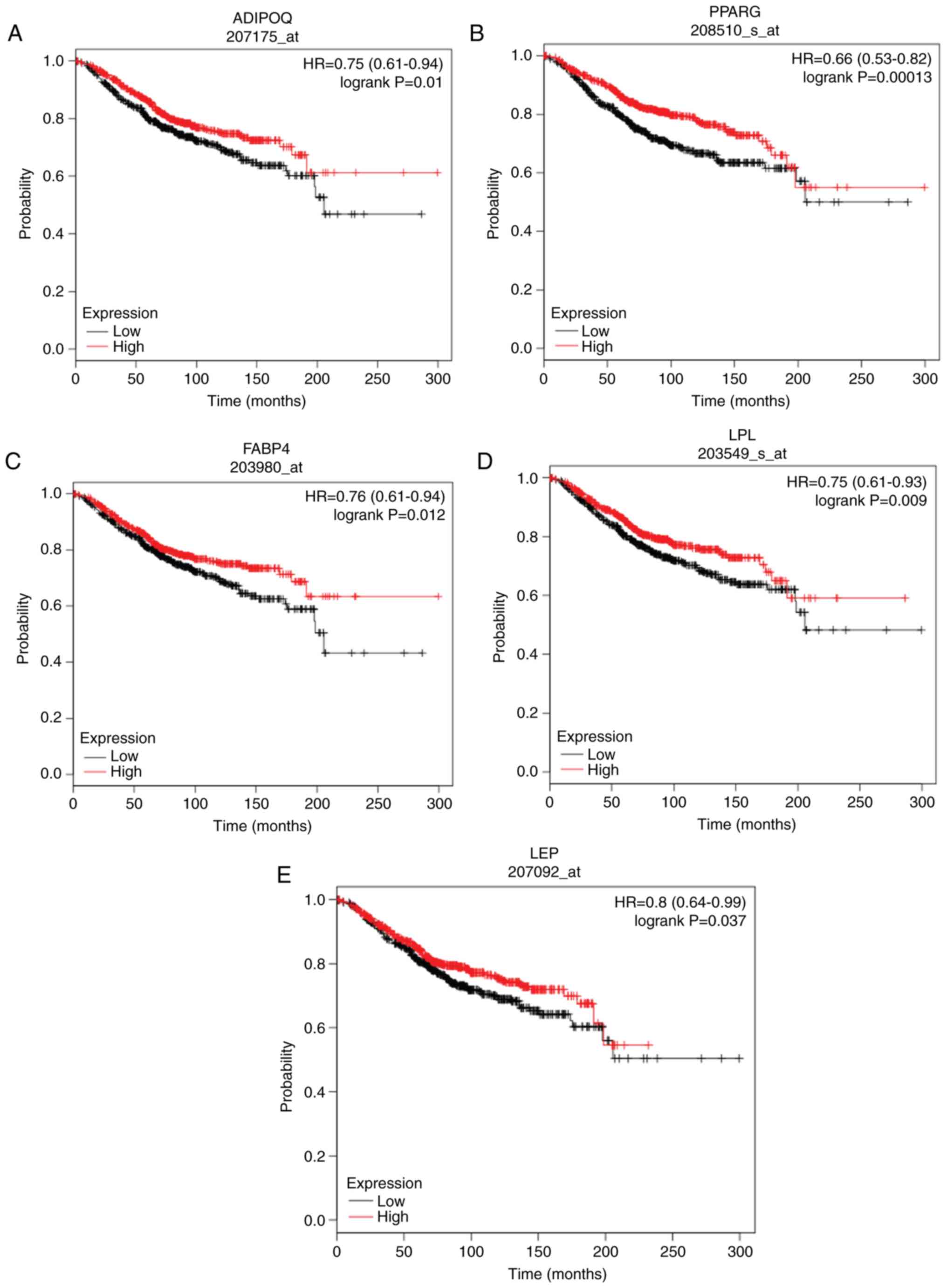

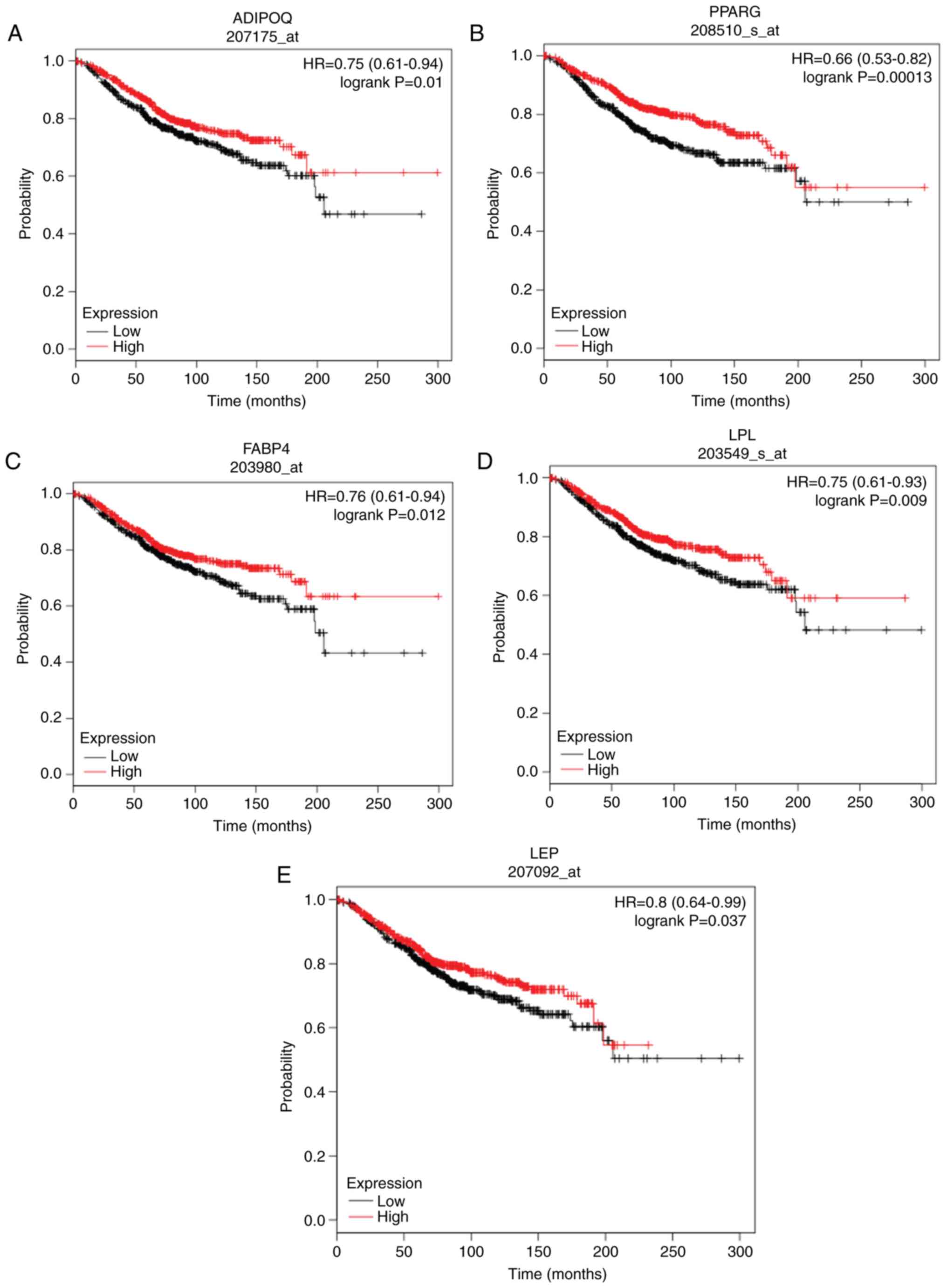

| Figure 5.Overall survival analysis of (A)

ADIPOQ, (B) PPARG, (C) FABP4, (D) LPL and (E) LEP in ductal

carcinoma in situ was performed using the Kaplan-Meier

plotter. Red and black represent high and low expression,

respectively. ADIPOQ, adiponectin; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator

activated receptor γ; FABP4, fatty acid-binding protein 4; LPL,

lipoprotein lipase; LEP, leptin; HR, hazard ratio. |

Survival analysis results of the hub

genes

The prognostic values of the identified hub genes in

patients with DCIS were investigated using the Kaplan-Meier

plotter. Only the low expression of ADIPOQ [hazard ratio (HR)=0.75;

95% confidence interval (CI), 0.61–0.94; log-rank P=0.01], PPARG

(HR=0.66; 95% CI, 0.53–0.82; log-rank P=0.0013), FABP4 (HR=0.76;

95% CI, 0.61–0.94; log-rank P=0.012), LPL (HR=0.75; 95% CI,

0.61–0.93; log-rank P=0.009) and LEP (HR=0.8; 95% CI, 0.64–0.99;

log-rank P=0.037) were significantly associated with poor OS in

patients with DCIS (Fig. 5). The

associations between the hub gene expression levels and

clinicopathological parameters of patients with DCIS are presented

in Table II. The expression levels

of LIPE, PNPLA2 and DGAT2 did not significantly influence the

prognosis of patients with DCIS (Fig.

S1).

| Table II.The correlation analysis of the hub

genes' expression levels and the clinicopathological parameters of

Ductal Carcinoma in situ of the Breast (data from the GSE59248

dataset). |

Table II.

The correlation analysis of the hub

genes' expression levels and the clinicopathological parameters of

Ductal Carcinoma in situ of the Breast (data from the GSE59248

dataset).

|

|

| ADIPOQ

expression |

| LEP expression |

| LPL expression |

| FABP4

expression |

| PPARG

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinical

parameter | No. of cases

(n) | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value |

|---|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤55 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 0.314 | 14 | 5 | 0.049 | 12 | 7 | 1.00 | 9 | 10 | 0.220 | 12 | 7 | 0.314 |

|

>55 | 27 | 13 | 14 |

| 12 | 15 |

| 18 | 9 |

| 8 | 19 |

| 13 | 14 |

|

| Tumor size

(cm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤3 | 22 | 14 | 8 | 0.678 | 14 | 8 | 0.242 | 15 | 7 | 0.417 | 12 | 10 | 0.419 | 12 | 10 | 0.419 |

|

>3 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 5 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 6 | 2 |

| 6 | 2 |

|

| ER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 15 | 6 | 9 | 0.105 | 6 | 9 | 0.400 | 7 | 8 | 0.210 | 8 | 7 | 1.00 | 9 | 6 | 1.00 |

|

Negative | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| 6 | 3 |

| 7 | 2 |

| 5 | 4 |

| 5 | 4 |

|

| PR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 12 | 4 | 8 | 0.100 | 4 | 8 | 0.220 | 3 | 9 | 0.003 | 5 | 7 | 0.414 | 8 | 4 | 0.680 |

|

Negative | 12 | 9 | 3 |

| 8 | 4 |

| 11 | 1 |

| 8 | 4 |

| 6 | 6 |

|

| HER2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0.387 | 5 | 4 | 1.00 | 7 | 2 | 0.080 | 6 | 3 | 0.660 | 6 | 3 | 0.660 |

|

Negative | 12 | 5 | 7 |

| 6 | 6 |

| 4 | 8 |

| 6 | 6 |

| 6 | 6 |

|

Discussion

DCIS is a heterogeneous disease and represents the

pre-invasive stage of BC (25).

Although the majority of patients with DCIS undergo breast excision

to remove the lesion, certain patients with DCIS may still develop

invasive BC (26). Therefore, it is

important to explore the molecular features of DCIS development and

to identify potential prognostic biomarkers.

The present study analyzed the gene expression data

of 46 DCIS and three normal breast tissues. A total of 316 DEGs

were identified, including 32 upregulated and 284 downregulated

genes. The identified DEGs could be classified into 22 protein

categories. Moreover, the results of the functional enrichment

analysis indicated that the DEGs were mostly associated with cell

parts, organelles, metabolic processes, cellular processes,

biological regulation, transporter activity and signal transducer

activity. A PPI network was constructed and eight hub genes were

selected for further investigation. The downregulation of ADIPOQ,

PPARG, FABP4, LPL and LEP was significantly associated with poor OS

in patients with DCIS.

ADIPOQ encodes an adipocytokine, adiponectin, which

is essential for metabolic and hormonal processes (27). A low level of plasma adiponectin has

been significantly associated with several types of cancer,

including colorectal and prostate cancer (28,29). It

was also reported that adiponectin may decrease cancer cell growth

by promoting the activity of autophagosomes and decreasing the

sequestosome 1/GAP-associated tyrosine phosphoprotein p62 signaling

pathway in BC (27). High ADIPOQ

expression may serve a protective role in BC (30), consistent with the results obtained

in the present study.

PPARG serves an important role in regulating

adipocyte differentiation by forming heterodimers with retinoid X

receptors (31). Several studies

have shown that PPARG serves an anti-inflammatory role and may

reduce the risk of breast cancer (32–34). The

expression level of PPARG was found to influence the susceptibility

to hepatocellular carcinoma (35)

and different types of cancer (36).

However, the association between PPARG and the risk of BC has not

been established (37,38). FABP4 is involved in lipoprotein

metabolism (39). A previous study

revealed that FABP4 increased cell apoptosis and decreased

proliferation (40). FABP4

overexpression has been reported to decrease hepatocellular

carcinoma cell growth through the snail family transcriptional

repressor 1/p-STAT3 signaling pathway in vitro and was

associated with tumor size and overall survival in hepatocellular

carcinoma (41).

LPL plays a critical role in lipid metabolism

(42). Studies have shown that LPL

may regulate metabolic pathways to provide additional energy for

cancer cells (43,44). Circulating LEP is usually secreted by

white adipose tissue and is involved in the regulation of

angiogenesis, energy balance, and immune and inflammatory responses

(45). Previous studies revealed

that LEP altered the cellular response to estrogens in BC and

served a role in mammary carcinogenesis (46,47).

Furthermore, LEP may promote cell cycle progression by upregulating

the levels of cyclin dependent kinase 2 and cyclin D1 (48). However, in the present study, LEP was

downregulated in DCIS tissues compared with normal tissues.

The remaining hub genes in the present study,

including LIPE, PNPLA2 and DGAT2, were also expressed at low levels

in DCIS tissues compared with normal breast tissues. However, these

genes were not associated with the prognosis of patients with DCIS.

It is worth noting that the GSE59248 dataset used in the present

study contained the gene expression profiles of only three normal

breast tissues. Therefore, future studies investigating the gene

expression profiles from multiple datasets are warranted.

The present study investigated the differences

between DCIS and normal breast tissues by integrating comprehensive

bioinformatics analyses. The top eight hub genes, namely LIPE,

PNPLA2, ADIPOQ, PPARG, FABP4, DGAT2, LPL and LEP, were identified

and considered to serve critical roles in the initiation of BC,

while only five of the hub genes, ADIPOQ, PPARG, FABP4, LPL and

LEP, were further found to be potential biomarkers for predicting

the prognosis of patients with DCIS. However, further research is

required to validate the results obtained in the present study.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are

available from GEO database, DAVID, STRING and GEPIA database, as

is mentioned in the Material and methods.

Author's contributions

MW and ZHM analyzed the data and wrote the

manuscript. ZHM supervised the study. Both authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was not necessary in this study

because public datasets were analyzed.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Fedewa SA,

Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Brawley OW and Wender RC: Cancer

screening in the United States, 2018: A review of current american

cancer society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening.

CA Cancer J Clin. 68:297–316. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kurian AW, Lichtensztajn DY, Keegan TH,

Nelson DO, Clarke CA and Gomez SL: Use of and mortality after

bilateral mastectomy compared with other surgical treatments for

breast cancer in California, 1998–2011. JAMA. 312:902–914. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

van der Veldt AA and Smit EF: Bevacizumab

in neoadjuvant treatment for breast cancer. N Engl J Med.

366:1637–1640. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Leal NF, Carrara HH, Vieira KF and

Ferreira CH: Physiotherapy treatments for breast cancer-related

lymphedema: A literature review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 17:730–736.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yeong J, Thike AA, Tan PH and Iqbal J:

Identifying progression predictors of breast ductal carcinoma in

situ. J Clin Pathol. 70:102–108. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ernster VL, Ballard-Barbash R, Barlow WE,

Zheng Y, Weaver DL, Cutter G, Yankaskas BC, Rosenberg R, Carney PA,

Kerlikowske K, et al: Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ in

women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst.

94:1546–1554. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD and

Page DL: The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ

of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30

years of long-term follow-up. Cancer. 103:2481–2484. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Abba MC, Drake JA, Hawkins KA, Hu Y, Sun

H, Notcovich C, Gaddis S, Sahin A, Baggerly K and Aldaz CM:

Transcriptomic changes in human breast cancer progression as

determined by serial analysis of gene expression. Breast Cancer

Res. 6:R499–R513. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Castro NP, Osório CA, Torres C, Bastos EP,

Mourão-Neto M, Soares FA, Brentani HP and Carraro DM: Evidence that

molecular changes in cells occur before morphological alterations

during the progression of breast ductal carcinoma. Breast Cancer

Res. 10:R872008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Schuetz CS, Michael B, Clare SE, Nieselt

K, Sotlar K, Walter M, Fehm T, Solomayer E, Riess O, Wallwiener D,

et al: Progression-specific genes identified by expression

profiling of matched ductal carcinomas in situ and invasive breast

tumors, combining laser capture microdissection and oligonucleotide

microarray analysis. Cancer Res. 66:5278–5286. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Choi Y, Lee HJ, Jang MH, Gwak JM, Lee KS,

Kim EJ, Kim HJ, Lee HE and Park SY: Epithelial-mesenchymal

transition increases during the progression of in situ to invasive

basal-like breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 44:2581–2589. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shah S, Brock EJ, Jackson RM, Ji K,

Boerner JL, Sloane BF and Mattingly RR: Downregulation of Rap1Gap:

A switch from DCIS to invasive breast carcinoma via ERK/MAPK

activation. Neoplasia. 20:951–963. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sakr RA, Weigelt B, Chandarlapaty S,

Andrade VP, Guerini-Rocco E, Giri D, Ng CK, Cowell CF, Rosen N,

Reis-Filho JS and King TA: PI3K pathway activation in high-grade

ductal carcinoma in situ-implications for progression to invasive

breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 20:2326–2337. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hannemann J, Velds A, Halfwerk JB, Kreike

B, Peterse JL and van de Vijver MJ: Classification of ductal

carcinoma in situ by gene expression profiling. Breast Cancer Res.

8:R612006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mi H, Huang X, Muruganujan A, Tang H,

Mills C, Kang D and Thomas PD: PANTHER version 11: Expanded

annotation data from gene ontology and reactome pathways, and data

analysis tool enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:D183–D189. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Huang da W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive

functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res.

37:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M,

Wyder S, Simonovic M, Santos A, Doncheva NT, Roth A, Bork P, et al:

The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein

association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res.

45:D362–D368. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lesurf R, Aure MR, Mørk HH, Vitelli V;

Oslo Breast Cancer Research Consortium (OSBREAC), ; Lundgren S,

Børresen-Dale AL, Kristensen V, Wärnberg F, Hallett M and Sørlie T:

Molecular features of subtype-specific progression from ductal

carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer. Cell Rep.

16:1166–1179. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Green GH and Diggle PJ: On the operational

characteristics of the benjamini and hochberg false discovery rate

procedure. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 6:Article272007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT and

Lin CY: CytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from

complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 8 (Suppl 4):S112014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Meghanathan N: Correlation coefficient

analysis: Centrality vs. maximal clique size for complex real-world

network graphs. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Györffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert

C, Budczies J, Li Q and Szallasi Z: An online survival analysis

tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer

prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer

Res Treat. 123:725–731. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tan PH: Pathology of ductal carcinoma in

situ of the breast: A heterogeneous entity in need of greater

understanding. Ann The Acad Med Singap. 30:671–677. 2001.

|

|

26

|

Gorringe KL and Fox SB: Ductal carcinoma

in situ biology, biomarkers, and diagnosis. Front Oncol. 7:2482017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chung SJ, Nagaraju GP, Nagalingam A,

Muniraj N, Kuppusamy P, Walker A, Woo J, Győrffy B, Gabrielson E,

Saxena NK and Sharma D: ADIPOQ/adiponectin induces cytotoxic

autophagy in breast cancer cells through STK11/LKB1-mediated

activation of the AMPK-ULK1 axis. Autophagy. 13:1386–1403. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Divella R, Daniele A, Mazzocca A, Abbate

I, Casamassima P, Caliandro C, Ruggeri E, Naglieri E, Sabbà C and

De Luca R: ADIPOQ rs266729 G/C gene polymorphism and plasmatic

adipocytokines connect metabolic syndrome to colorectal cancer. J

Cancer. 8:1000–1008. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Canto P, Granados JB, Feria-Bernal G,

Coral-Vázquez RM, García-García E, Tejeda ME, Tapia A, Rojano-Mejía

D and Méndez JP: PPARGC1A and ADIPOQ polymorphisms are associated

with aggressive prostate cancer in Mexican-Mestizo men with

overweight or obesity. Cancer Biomark. 19:297–303. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Delort L, Jardé T, Dubois V, Vasson MP and

Caldefie-Chézet F: New insights into anticarcinogenic properties of

adiponectin: A potential therapeutic approach in breast cancer?

Vitam Horm. 90:397–417. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

He W: PPARgamma2 polymorphism and human

health. PPAR Res. 2009:8495382009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Crusz SM and Balkwill FR: Inflammation and

cancer: Advances and new agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 12:584–596.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Robbins GT and Nie D: PPAR gamma,

bioactive lipids, and cancer progression. Front Biosci (Landmark

Ed). 17:1816–1834. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Khandekar MJ, Cohen P and Spiegelman BM:

Molecular mechanisms of cancer development in obesity. Nat Rev

Cancer. 11:886–895. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang S, Jiang J, Chen Z, Wang Y, Tang W,

Chen Y and Liu L: Relationship of PPARG, PPARGC1A, and PPARGC1B

polymorphisms with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in an

eastern Chinese Han population. Onco Targets Ther. 11:4651–4660.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Xu W, Li Y, Wang X, Chen B, Liu S, Wang Y,

Zhao W and Wu J: PPARgamma polymorphisms and cancer risk: A

meta-analysis involving 32,138 subjects. Oncol Rep. 24:579–585.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gallicchio L, McSorley MA, Newschaffer CJ,

Huang HY, Thuita LW, Hoffman SC and Helzlsouer KJ: Body mass,

polymorphisms in obesity-related genes, and the risk of developing

breast cancer among women with benign breast disease. Cancer Detect

Prev. 31:95–101. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wu MH, Chu CH, Chou YC, Chou WY, Yang T,

Hsu GC, Yu CP, Yu JC and Sun CA: Joint effect of peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma genetic polymorphisms and

estrogen-related risk factors on breast cancer risk: Results from a

case-control study in Taiwan. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 127:777–784.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Furuhashi M: Fatty acid-binding protein 4

in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb.

26:216–232. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li H, Xiao Y, Tang L, Zhong F, Huang G, Xu

JM, Xu AM, Dai RP and Zhou ZG: Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein

promotes palmitate-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis

in macrophages. Front Immunol. 9:812018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhong CQ, Zhang XP, Ma N, Zhang EB, Li JJ,

Jiang YB, Gao YZ, Yuan YM, Lan SQ, Xie D and Cheng SQ: FABP4

suppresses proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma

cells and predicts a poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cancer Med. 7:2629–2640. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Davies BS, Beigneux AP, Fong LG and Young

SG: New wrinkles in lipoprotein lipase biology. Curr Opin Lipidol.

23:35–42. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Prieto D and Oppezzo P: Lipoprotein lipase

expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: New insights into

leukemic progression. Molecules. 22:20832017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Heintel D, Kienle D, Shehata M, Kröber A,

Kroemer E, Schwarzinger I, Mitteregger D, Le T, Gleiss A,

Mannhalter C, et al: High expression of lipoprotein lipase in poor

risk B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 19:1216–1223.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Garofalo C and Surmacz E: Leptin and

cancer. J Cell Physiol. 207:12–22. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Garofalo C, Sisci D and Surmacz E: Leptin

interferes with the effects of the antiestrogen ICI 182,780 in

MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 10:6466–6475. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hu X, Juneja SC, Maihle NJ and Cleary MP:

Leptin-a growth factor in normal and malignant breast cells and for

normal mammary gland development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 94:1704–1711.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Okumura M, Yamamoto M, Sakuma H, Kojima T,

Maruyama T, Jamali M, Cooper DR and Yasuda K: Leptin and high

glucose stimulate cell proliferation in MCF-7 human breast cancer

cells: Reciprocal involvement of PKC-alpha and PPAR expression.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1592:107–116. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|