Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal

gynecologic malignancy worldwide, with a 5-year survival rate of

46.5% between 2005 to 2011 (1), as

well as 230,000 new cases and 150,000 deaths annually in 2012

(2). Due to the increasing research

on traditional and novel targeted drugs, the lives of patients with

EOC are being prolonged. Researchers have revealed that after

treatment with surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy, 50% of

patients with EOC with stage III disease could live for >5 years

(3). At present, the median survival

of recurrent patients sensitive to platinum is 3 years; however,

for patients with EOC who are resistant to platinum it is only 1

year (4). The remission rate of

patients with EOC has increased markedly with the combination of

platinum-based traditional chemotherapy and targeting therapies,

including VEGF inhibitors and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

inhibitors (3,5). However, these two classes of drug are

only used for patients who are sensitive to platinum (6). Therefore, exploring novel efficient

targeted drugs that can enhance the sensitivity of patients with

EOC to platinum is of significance to improve patient

prognosis.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are a key mechanism

of platinum-based chemotherapy in EOC. When entering EOC cells,

platinum binds to DNA spontaneously to induce platinum-DNA

cross-links that damage the normal structure and function of DNA

(7). As a result, cell cycle

progression is blocked and cell death is induced (8,9). DNA

damage repair could be induced by excessive DNA DSB aggregation in

EOC cells, which causes cells to be resistant to platinum (9). The sensitivity of EOC cells to platinum

depends on their ability to induce DNA damage repair spontaneously

(5). DNA DSBs are mainly repaired by

homologous recombination signaling pathways (10). Previous research has demonstrated

that homologous recombination defects are obvious in patients with

ovarian cancer with BRCA1 gene mutations, resulting in higher

sensitivity to chemotherapy than in patients without BRCA1 gene

mutations (11). It is estimated

that ~50% of high-grade serous adenocarcinomas feature homologous

recombination (3,12). Therefore, identifying molecules that

can inhibit homologous recombination in EOC cells is key to

enhancing the sensitivity of patients with EOC to platinum.

Kin17 DNA and RNA binding protein (KIN17), a DNA-

and RNA-binding protein that is extremely well conserved across

biological evolution, is considered critical to the proliferation

and survival of mammalian cells, including normal and cancerous

cells (13). Importantly, the KIN17

protein has been demonstrated to be involved in the DNA damage

repair process by regulating the homologous recombination signaling

pathway (14,15). When the KIN17 gene is silenced, DNA

replication, DNA damage repair, cell cycle progression and

proliferation are inhibited in breast cancer cells; however,

sensitivity to chemotherapy is increased (16). Proliferation, invasion and metastasis

are inhibited by downregulation of the KIN17 protein, thereby

inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in cervical cancer cells

(17). The KIN17 protein can induce

the proliferation of liver cancer cells (18), and its upregulation is associated

with the invasion and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer

(19). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the effect of KIN17 in ovarian cancer remains unclear

and requires further exploration.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the

possible association between KIN17 expression and the

clinical/pathological features, as well as the overall survival

(OS) of patients with EOC, and to verify the effects of KIN17 on

EOC in vitro in order to provide a theoretical basis for

future research on novel targeted drugs.

Materials and methods

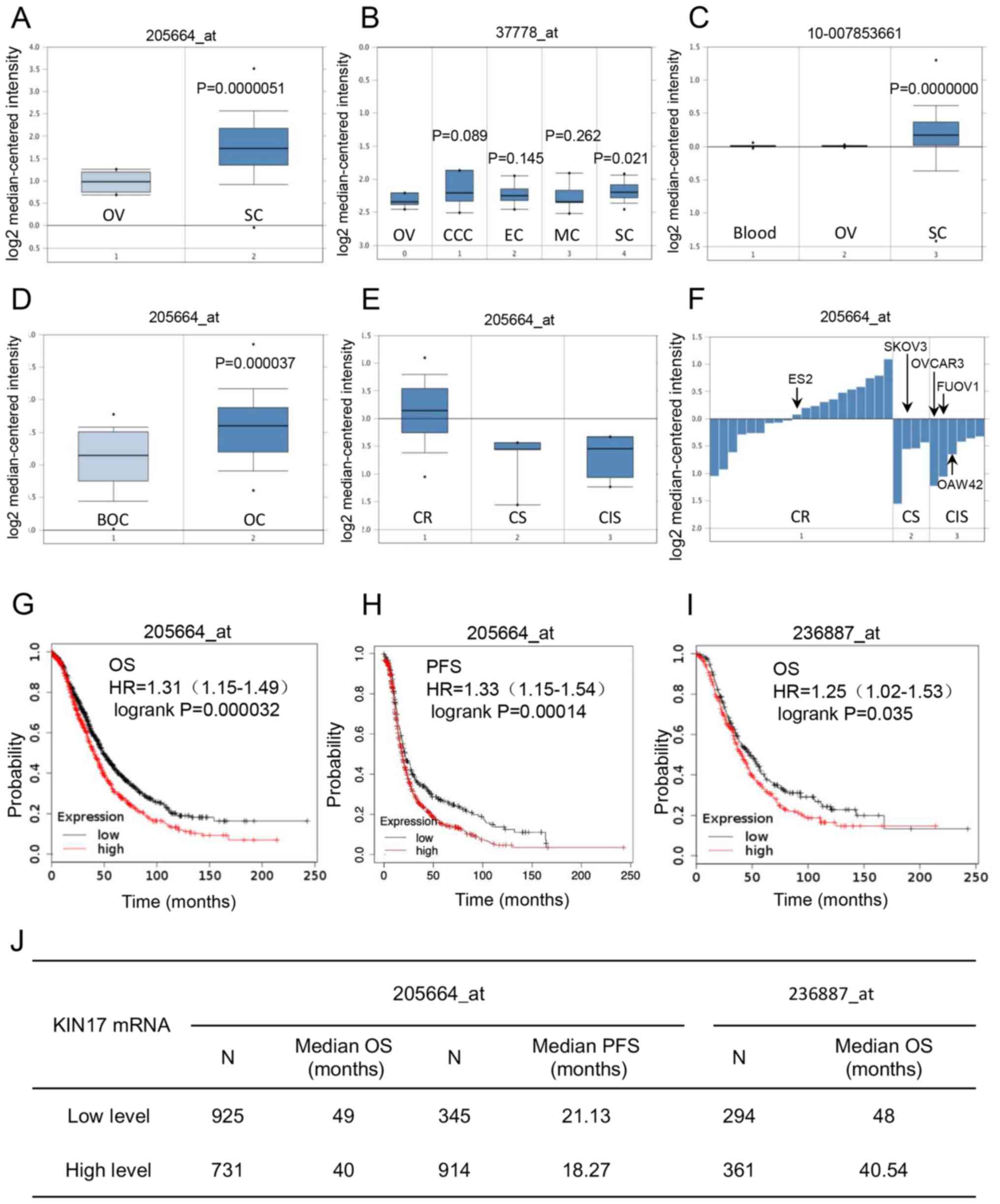

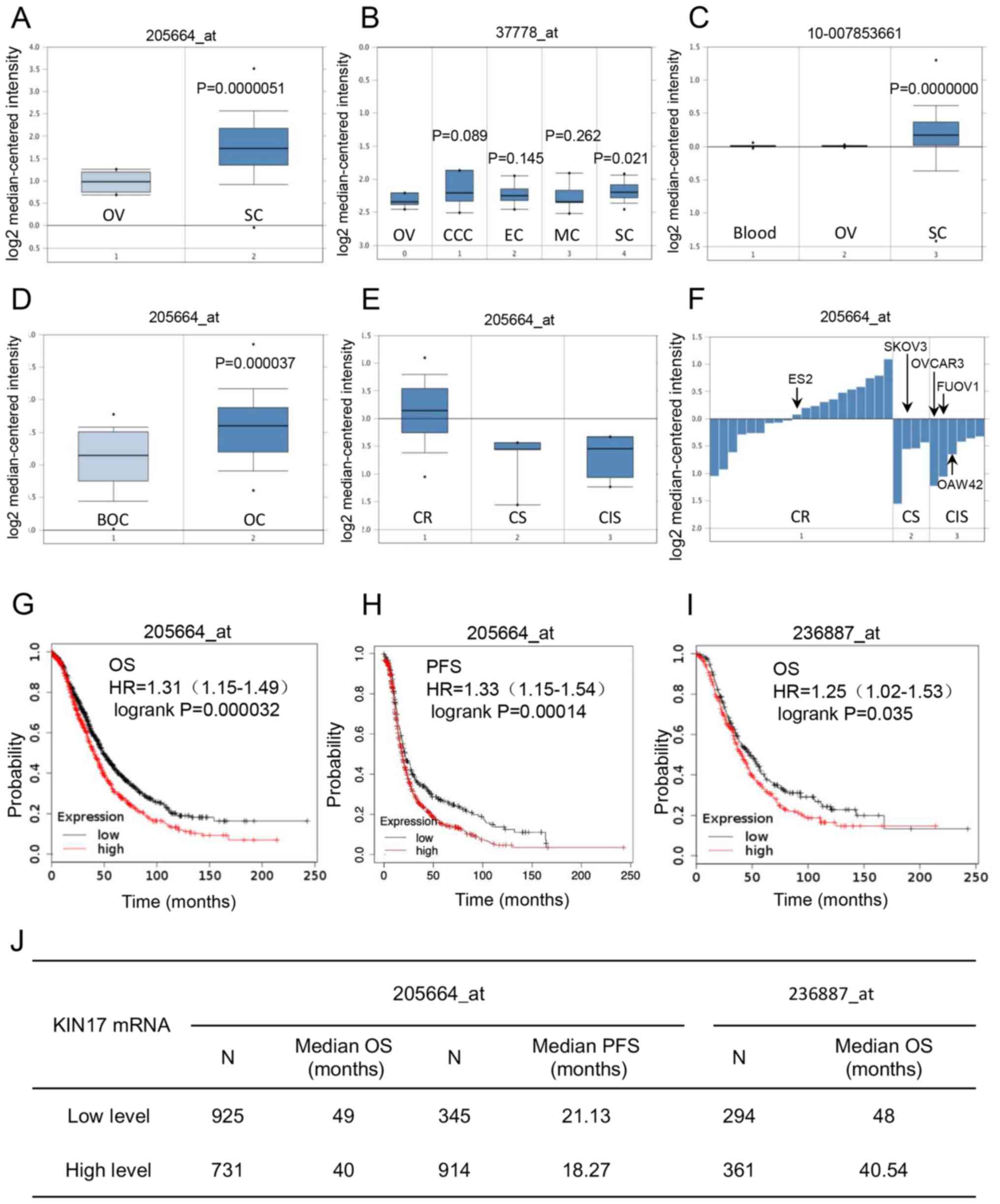

Bioinformatics analysis

The Oncomine database (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html) was used

to analyze the difference in KIN17 gene expression between EOC and

normal ovarian tissues [datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) Ovarian (Affymetrix ID: 205664_at), Lu Ovarian (Affymetrix

ID: 37778_at) (20) and TCGA Ovarian

2 (Affymetrix ID: 0-007853661)], as well as between borderline

ovarian surface epithelial-stromal tumor and ovarian cancer tissues

[dataset from Anglesio Ovarian (GSE12172, Affymetrix ID:

205664_at)] (21). Furthermore, the

association between KIN17 mRNA expression and the sensitivity of

EOC cells to platinum was examined using the Oncomine database

[dataset derived from Gyorffy CellLine (GSE11812, Affymetrix ID:

205664_at)] (22). The Kaplan-Meier

database (http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&cancer=ovar)

was used to examine the association between the transcriptional

levels of KIN17 and the prognoses of patients with ovarian cancer.

All the data in this part were analyzed from 15 datasets (23). The follow-up time was between 2 and

240 months. The expression range of the probe in 205664_at was

between 4 and 1,845; 533 and 377 were selected as the cut-off

values for OS and progression-free survival (PFS) analysis,

respectively. The expression range of the probe in 236887_at was

between 6 and 558; 127 was selected as the cut-off value for OS

analysis. All cut-off values between the lower and upper quartiles

were computed, and the best performing threshold was used as the

cut-off.

Specimens

The present study was approved by the Research

Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of Jilin University

(Changchun, China). All patients were informed and agreed to

participate in the present study. Paraffin-embedded specimens were

collected at The Second Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun,

China) from 56 patients with EOC and five patients with mucous

cystadenoma who were diagnosed between January 2012 and January

2018. The median age of the patients was 52 years (range, 32–76

years). All patients were female. The inclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Initially diagnosed with EOC and treated with early

comprehensive staging laparotomy or ideal cytoreductive surgery;

ii) the EOC diagnosis was confirmed by the Pathology Department of

The Second Hospital of Jilin University; iii) postoperative

pathology results were measured strictly by Federation

International of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging criteria

(24); iv) standardized

platinum-based chemotherapy was administered postoperatively; and

v) complete follow-up data were available. The exclusion criteria

were as follows: i) Individual history of other malignant tumors;

ii preoperative chemo/radiotherapy; and iii) secondary ovarian

cancer. All patient blood samples were collected before surgery and

immediately analyzed for the levels of CA125 and human epididymis

protein 4 (HE4). Fresh frozen (−80°C) specimens, including cancer

tissues and adjacent tissues, were collected from 20 patients with

EOC who were diagnosed at the same hospital between February 2018

and August 2019. All patients with EOC received standard

platinum-based chemotherapy following cytoreductive surgeries. As

shown in Table I, available

clinical/pathological data were extracted from the Medical Record

Database of The Second Hospital of Jilin University. All 56

patients with EOC were followed up, and the OS of these patients

was calculated. The median follow-up for patients with EOC was 31

months, ranging between 7 and 77 months.

| Table I.Association between KIN17 protein

expression and clinical features of patients with epithelial

ovarian cancer. |

Table I.

Association between KIN17 protein

expression and clinical features of patients with epithelial

ovarian cancer.

|

|

| KIN17

expression |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinical

features | No. of cases

(%) | High expression,

n | Low expression,

n | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<52 | 27 (48.21) | 16 | 11 |

|

|

|

≥52 | 29 (51.79) | 16 | 13 | 0.095 | 0.757 |

| FIGO stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I+II | 23 (41.07) | 10 | 13 |

|

|

|

III+IV | 33 (58.93) | 22 | 11 | 2.976 | 0.085 |

| Tumor size, cm |

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤8 | 28 (50.00) | 14 | 14 |

|

|

|

>8 | 28 (50.00) | 18 | 10 | 1.167 | 0.280 |

| EOC

typea |

|

|

|

|

|

| Type

I | 26 (46.43) | 14 | 12 |

|

|

| Type

II | 30 (53.57) | 18 | 12 | 0.215 | 0.643 |

| Pathological

grade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Low

level | 23 (41.07) | 13 | 10 |

|

|

| High

level | 33 (58.93) | 19 | 14 | 0.006 | 0.938 |

| Ascites volume,

ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<500 | 31 (55.36) | 16 | 15 |

|

|

|

≥500 | 25 (44.64) | 16 | 9 | 0.867 | 0.352 |

| Lymphatic

metastasisc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 17 (37.78) | 13 | 4 |

|

|

|

Negative | 28 (62.22) | 12 | 16 | 4.840 | 0.028b |

| CA125,

U/mld |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<500 | 25 (47.17) | 17 | 8 |

|

|

|

≥500 | 28 (52.83) | 15 | 13 | 1.149 | 0.284 |

| HE4,

pmol/ld |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<500 | 26 (68.42) | 17 | 9 |

|

|

|

≥500 | 12 (31.58) | 6 | 6 | 0.813 | 0.367 |

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed as

described previously (25). Briefly,

after being fixed in 10% formalin at room temperature for 24 h, EOC

tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 3-µm thick sections.

After being deparaffinized by xylol and rehydrated by descending

alcohol series (100, 85 and 70% alcohol, 10 min for each

concentration) at room temperature, the sections were soaked in

EDTA retrieval buffers (cat. no. AR0023; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd.) and heated in a microwave oven at 98°C for 15

min. Then the sections were cooled naturally at room temperature.

Non-specific binding was blocked using 5% bovine serum albumin

(BSA; cat. no. AR1006; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) at

room temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, the histological

sections were stained with rabbit anti-KIN17 antibody (dilution,

1:100; cat. no. PB0639; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.)

at 4°C overnight. Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish

peroxidase (dilution, 1:200; cat. no. S0001; Affinity Biosciences)

was used as the secondary antibody, and this staining procedure was

carried out at 37°C for 30 min. Reactive products were visualized

with 3,3′-diaminobenzidene (cat. no. AR1022; Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology, Ltd.) as the chromogen, and the sections

were counterstained with hematoxylin (0.1%; cat. no. AR0005; Wuhan

Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 min.

Histological images were captured under a light microscope (BX51;

Olympus Corporation) with an objective magnification of ×200 or

×400. The intensity was scored as follows: 0, no color; 1, light

yellow; 2, yellow brown; and 3, brown. The proportion of positive

tumor cells was scored as: 0, 0–4; 1, 5–24; 2, 25–49; 3, 50–74; and

4, 75–100%. The overall score of each sample was obtained by

multiplying the two scores. A score of >4 was defined as high

KIN17 expression, and a score of ≤4 was defined as low KIN17

expression. The IHC staining was double-blinded and scored

independently by two experienced pathologists working at The

Pathology Department of the Second Hospital of Jilin

University.

Western blot analysis

Protein samples from fresh frozen tissues or stably

transfected cells were extracted using cold RIPA lysis buffer (cat.

no. P0013K; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Subsequently, the

protein samples were quantified according to the Bradford method

using an Easy Protein Quantitative Kit (cat. no. DQ101-01; TransGen

Biotech Co., Ltd.). A total of 30 µg protein sample was added to

each lane, resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE, separated electrophoretically

and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD

Millipore). The non-specific binding sites of the membrane were

blocked with 5% dried skim milk at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the

membrane was incubated with primary antibodies, including rabbit

anti-KIN17 (dilution, 1:2,000; cat. no. PB0639; Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology, Ltd.) and mouse anti-β-actin (dilution,

1:1,500; cat. no. HC201-01; TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 4°C

overnight, followed by incubation with horseradish

peroxidase-tagged goat anti rabbit IgG (dilution, 1:4,000; cat. no.

S0001) and goat anti mouse IgG (dilution, 1:4,000; cat. no. S0002)

(both Affinity Biosciences) at room temperature for 2 h,

respectively. Finally, the protein expression levels were detected

with an electrochemiluminescence plus kit (cat. no. KF001; Affinity

Biosciences), and the densities of the specific bands were

semi-quantified using an imaging densitometer (Clinx Science

Instruments Co., Ltd.) and the software Gel Analysis (Clinx Science

Instruments Co., Ltd.) that is provided with the densitometer.

Cell culture and stably transfected

cell line development

The human EOC cell line SKOV3 was originally

obtained from The Basic Medical College of Jilin University

(Changchun, China). The cells were cultured in Iscove's modified

Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2.

The construction of short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-KIN17

(NM_012311.3) was performed by GeneCopoeia, Inc. The stably

transfected SKOV3 cell line was transfected with shRNA-KIN17 (cat.

no. CS-RSH086442-CU6-01; GeneCopoeia, Inc.) based with the plasmid

psi-U6 (GeneCopoeia, Inc.) using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocols. SKOV3 cells were seeded into a six-well

plate at a density of 8×105 cells/well. Then, 2.5 µg

shRNA-KIN17 or shRNA-Scramble (treatment groups) and only

Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (negative control) were added into the

wells of different groups. Following incubation at 37°C for 96 h,

the transfected cells were selected with 5 µg/ml puromycin (cat.

no. P1033; Biotopped Life Sciences) for 2 weeks before

experimentation, and the surviving cells were continuously cultured

as a stably transfected cell line. The transfection efficiency was

detected by fluorescence microscopy, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blotting.

RT-qPCR

RNA was extracted from the stably transfected cells

using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

followed by quantification with a NanoDrop 2000 instrument

(NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Following

reverse transcription with a cDNA synthesis kit (Beijing Transgen

Biotech Co., Ltd.), cDNA was used for PCR amplification using a

SYBR Green real-time PCR kit (Beijing Transgen Biotech Co., Ltd.)

using an ABI-Q3 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

primers used were as follows: KIN17 Gene forward,

5′-GGACCCAGAAACTATCCGCC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTCCCTTCCAGGCCTCTTCT-3′;

and GAPDH forward, 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′. GAPDH was used as an internal control

gene. Reverse transcription was performed with Anchored Oligo(dT)

at 42°C for 15 min, followed by incubating with Random Primer (N9)

at 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 sec using a

96-well Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). PCR was

performed at 94°C for 30 sec, followed by 45 cycles of

amplification at 94°C for 5 sec, 51°C for 15 sec and 72°C for 10

sec using an ABI-Q3 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (26).

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

After being transfected with shRNA-KIN17 or shRNA

Scramble, these SKOV3 cells and untreated SKOV3 cells were seeded

into 96-well plates (1,000 cells/well). After 24, 48, 72, 96 and

120 h, CCK-8 reagent (10 µl/well; BIOSS) was added to each well.

Following culture at 37°C for 2 h, the absorbance of each well was

measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Cytation 5; BioTek

Instruments, Inc.). The stably transfected SKOV3 cells were seeded

into 96-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well and

incubated at 37°C overnight. After exposure to cisplatin at 0, 0.5,

1, 2, 4, 8 or 16 µg/ml at 37°C for 48 h, CCK-8 reagent (10 µl/well;

BIOSS) was used to detect the proliferation rates of SKOV3 cells

and sensitivity of SKOV3 cells to cisplatin at 37°C for 2 h.

Transwell assay

For the migration assay, following 12 h of serum

starvation treatment, untreated SKOV3, shRNA-KIN17-transfected

SKOV3 and shRNA-Scramble-transfected SKOV3 cells were adjusted to a

density of 3×105 cells/ml using serum-free Iscove's

modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; containing or not containing

cisplatin at 1 µg/ml). Subsequently, 100 µl single cell suspension

was added to the apical chamber (8-µm polycarbonate membrane;

Corning, Inc.), and 600 µl IMDM with 10% FBS (containing or not

containing cisplatin at 1 µg/ml) was added to the bottom chamber.

The cells were allowed to migrate through the polycarbonate

membrane for 40 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Subsequently, the

cells remaining on the upper surface were wiped off with a cotton

ball. The migration cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at

room temperature for 30 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet

(cat. no. C6470; Biotopped Life Sciences) at room temperature for

10 min, and then observed using an optical light microscope

(magnification, ×200). Subsequently, the cells were observed and

quantified in five random fields of view (magnification, ×200).

Mean integrated optical density (IOD) was measured using Image-Pro

Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc). The IOD fold changes of

the treatment groups were also analyzed. All experiments were

performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean and ± standard

deviation. The association between the expression levels of KIN17

and the clinical/pathological features of patients with EOC was

analyzed using the χ2 test. Student's two-tailed t-test

was used to verify significant differences in KIN17 expression

between EOC and EOC-adjacent tissues. In addition, one-way ANOVA

and Tukey's test were used for multiple comparisons. OS curves were

generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a

log-rank test. Univariate analyses were performed using

Kaplan-Meier. Multivariate analyses were performed using Cox

regression models. All experiments were repeated three times

independently. All data were analyzed using SPSS software (version

23.0; IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Association between KIN17 DNA/mRNA

levels and EOC

Using the Oncomine database, the association between

the gene expression of KIN17 and EOC was analyzed. As shown in

Fig. 1A, compared with that in

normal ovary tissues, the transcription of KIN17 was upregulated in

ovarian serous adenocarcinoma tissues (P<0.05), which was also

demonstrated in Fig. 1B (P<0.05).

Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in KIN17 mRNA

expression between normal ovary tissues and other EOC tissues,

including ovarian mucinous, endometrioid and clear cell

adenocarcinoma tissues (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1C shows that the KIN17 DNA

levels were upregulated in ovarian serous adenocarcinoma tissues

compared with ovarian tissues (P<0.05). Furthermore, the

transcription of KIN17 was higher in ovarian cancer tissues than

borderline ovarian surface epithelial-stromal tumor tissues

(P<0.05; Fig. 1D). Gyorffy Cell

Line Statistics obtained and analyzed from the Oncomine database

revealed that cisplatin-resistant cancer cell lines exhibited high

mRNA expression levels of KIN17 compared with cisplatin-sensitive

and intermediate sensitive cancer cell lines (Fig. 1E). Additionally, KIN17 mRNA

expression was identified to be increased in the ES-2 cell line, a

cisplatin-resistant EOC cell line with a KIN17 expression value of

0.08, compared with the OVCAR-3 cells with an expression value of

−1.24, FU-OV-1 cells with an expression value of −1.07 and OAW42

cells with an expression value of −0.66 (cisplatin sensitivity), as

well as the SKOV3 cell line with an expression value of −0.56

(cisplatin intermediate sensitivity; Fig. 1F).

| Figure 1.Bioinformatics analysis of the role

of KIN17 gene expression in the development of OC and prognosis of

patients with OC. (A) mRNA expression levels of KIN17 in OV and SC

tissues (Affymetrix ID: 205664_at; 1. OV, n=8; 2. SC, n=586). (B)

mRNA expression levels of KIN17 in OV and EOC tissues (Affymetrix

ID: 37778_at; 0. OV, n=5; 1. CCC, n=7; 2. EC, n=9; 3. MC, n=9; 4.

SC, n=20). (C) DNA expression levels of KIN17 in blood, OV and SC

tissues (Affymetrix ID: 10-007853661; 1. Blood, n=431; 2. OV,

n=130; 3. SC, n=607). (D) mRNA expression levels of KIN17 in BOC

and OC tissues (Affymetrix ID: 205664_at; 1. BOC, n=30; 2. OC,

n=44). (E) mRNA expression levels of KIN17 in Gyorffy cell lines

(Affymetrix ID: 205664_at; 1. CR, n=20; 2. CS, n=6; 3. CIS, n=4).

(F) mRNA expression levels of KIN17 in different EOC cell lines

(Affymetrix ID: 205664_at; 1. CR; 2. CS; 3. CIS). (G) Association

between KIN17 mRNA expression and the OS of patients with OC

(Affymetrix ID: 205664_at). (H) Association between KIN17 mRNA

expression and the PFS of patients with OC (Affymetrix ID:

205664_at). (I) Association between KIN17 mRNA expression and the

OS of patients with OC (Affymetrix ID: 236887_at). (J) Sample

numbers and median survival (OS or PFS) of patients with OC in

different datasets. BOC, borderline ovarian surface

epithelial-stromal tumor; CCC, clear cell adenocarcinoma; CIS,

cisplatin intermediate sensitivity; CR, cisplatin resistant; CS,

cisplatin sensitivity; EC, endometrioid adenocarcinoma; EOC,

epithelial ovarian cancer; HR, hazard ratio; KIN17, Kin17 DNA and

RNA binding protein; MC, mucinous adenocarcinoma; OC, ovarian

cancer; OS, overall survival; OV, normal ovary; PFS,

progression-free survival; SC, ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. |

Association between KIN17 mRNA

expression and the prognosis of patients with EOC

Using the Kaplan-Meier database, the association

between the transcription of KIN17 and EOC prognosis was

investigated. As shown in Fig. 1G, I and

J, compared with patients with EOC with low mRNA expression

levels of KIN17, patients with EOC with high expression levels of

KIN17 had a poorer OS (median, 49 months vs. 40 months in

205664_at, P<0.01; median, 48 months vs. 40.54 months in

236887_at, P<0.05). Furthermore, compared with patients with EOC

with low mRNA expression levels of KIN17, patients with EOC with

high expression levels of KIN17 had a poorer PFS (median, 21.13

months vs. 18.27 months in 205664_at; P<0.01; Fig. 1H and J).

Difference in KIN17 expression between

EOC and EOC-adjacent tissues

The expression levels of KIN17 were detected by

western blotting in EOC and adjacent tissues. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, compared with EOC-adjacent

tissues, EOC tissues exhibited higher KIN17 protein expression

(P<0.05).

| Figure 2.Analysis of the roles of KIN17

protein in the development and predictive prognosis of patients

with EOC using IHC staining and western blotting. (A) Western blot

of KIN17 in EOC and adjacent tissues. (B) Analysis of KIN17

expression level in EOC and adjacent tissues. (C) Typical IHC

staining images for HGSC, HGMC, HGEC, MD, LGSC, LGMC, LGEC and CCC

(magnification, ×200 or ×400). MD was used as a negative control.

KIN17 protein expression in the cytoplasm was indicated using red

arrows and KIN17 protein expression in the nucleus was indicated

using black arrows. (D) Overall survival of patients with EOC

according to Federation International of Gynecology and Obstetrics

stages, EOC types, pathological grades, lymphatic metastasis and

KIN17 expression. **P<0.01 vs. adjacent tissue group. CCC, clear

cell carcinoma; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; HGEC, high-grade

endometrioid carcinoma; HGMC, high-grade mucous carcinoma; HGSC,

high-grade serous carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemical; KIN17, Kin17

DNA and RNA binding protein; LGEC, low-grade endometrioid

carcinoma; LGMC, low-grade mucous carcinoma; LGSC, low-grade serous

carcinoma; MD, mucous cystadenoma. |

Analysis of the association between

KIN17 expression and the clinical/pathological features of patients

with EOC

Using IHC staining and scoring, the expression

levels of KIN17 in EOC tissues were used to divide cases into low

expression (score ≤4; 24 cases) and high expression (score >4;

32 cases) groups. Cellular yellowish or brownish staining was

scored as positive. IHC staining of KIN17 in various pathologic

categories of low grade or high grade is shown in Fig. 2C. The nuclear and cytoplasmic

expression of KIN17 is also indicated in Fig. 2C. In the present study, the median

age of the 56 patients with EOC was 52 years. All features,

including age, preoperative CA125 and HE4, tumor size, lymphatic

metastasis, FIGO stage, EOC type, pathological grade, and ascites

volume, are summarized in Table I.

Following further analysis, only lymphatic metastasis was

identified to be associated with the expression levels of KIN17

(P<0.05). More specifically, the protein expression levels of

KIN17 were higher in patients with EOC who underwent lymphatic

metastasis compared with in patients with EOC without lymphatic

metastasis (76.47 vs. 42.85%; P<0.05).

Analysis of risk factors for the OS of

patients with EOC

After following up the 56 patients with EOC, 3- and

5-year OS rates were calculated, and all features, as well as the

expression levels and location of KIN17, were evaluated (Table II). As shown in Table II and Fig. 2D, compared with those of patients

with EOC with high protein expression levels of KIN17, both the 3-

and 5-year OS rates were higher in patients with EOC with low

protein expression levels of KIN17 (3-year OS, 82.0% in the EOC

patients with low protein expression levels of KIN17 vs. 56.8% in

the EOC patients with high protein expression levels of KIN1;

5-year OS, 60.7 vs. 35.4%; P<0.05). This data suggested that

high KIN17 expression was one of the risk factors for OS in

patients with EOC. However, no association was observed between the

location of KIN17 expression and OS (P>0.05). Furthermore, it

was identified that advanced stage (stage III+IV), type II, high

grade and positive lymphatic metastasis were risk factors for the

OS of patients with EOC (Table II;

Fig. 2D; P<0.05).

| Table II.Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis of

OS in patients with EOC. |

Table II.

Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis of

OS in patients with EOC.

| Clinical

features | No. of cases | 3-year OS, % | 5-year OS, % | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

<52 | 27 | 72.6 | 25.8 |

|

|

≥52 | 29 | 64.2 | 52.3 | 0.851 |

| FIGO stage |

|

|

|

|

|

I+II | 23 | 91.1 | 72.9 |

|

|

III+IV | 33 | 51.6 | 24.1 | 0.001a |

| Tumor size, cm |

|

|

|

|

| ≤8 | 28 | 70.4 | 55.4 |

|

|

>8 | 28 | 65.5 | 36.8 | 0.636 |

| EOC type |

|

|

|

|

| I | 26 | 84.3 | 54.5 |

|

| II | 30 | 52.4 | 36.9 | 0.036a |

| Pathological

grade |

|

|

|

|

|

Low | 23 | 86.5 | 76.9 |

|

|

High | 33 | 54.5 | 23.3 | 0.006a |

| Ascites volume,

ml |

|

|

|

|

|

<500 | 31 | 73.6 | 57.2 |

|

|

≥500 | 25 | 61.7 | 36.0 | 0.488 |

| Lymph node

metastasisb |

|

|

|

|

|

Positive | 17 | 59.6 | – |

|

|

Negative | 28 | 81.6 | 58.7 | 0.028a |

| CA125, U/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

<500 | 25 | 67.0 | 48.0 |

|

|

≥500 | 28 | 66.2 | 52.9 | 0.794 |

| HE4, pmol/l |

|

|

|

|

|

<500 | 26 | 56.1 | 48.1 |

|

|

≥500 | 12 | 91.7 | 67.9 | 0.150 |

| KIN17

expression |

|

|

|

|

| High

level | 32 | 56.8 | 35.4 |

|

| Low

level | 24 | 82.0 | 60.7 | 0.024a |

| KIN17

localization |

|

|

|

|

|

Cytoplasm | 18 | 62.9 | 52.4 |

|

|

Nucleus | 26 | 63.2 | 45.1 | 0.585 |

In addition, to exclude the impact of confounding

factors, Cox regression analysis was utilized to verify the

independent risk factors for OS in patients with EOC. It was

concluded that both advanced stage and high expression levels of

KIN17 were independent risk factors for OS in patients with EOC

(Table III). More precisely, the

risk of death in patients with advanced-stage EOC was 6.510 times

higher than that in patients who were at an early stage (stage

I+II; P<0.05). The risk of death in patients with EOC with high

expression levels of KIN17 was 2.828 times greater than that in

patients with low expression (P<0.05).

| Table III.Multivariate Cox regression analysis

of overall survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. |

Table III.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis

of overall survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

| Prognostic

factors | Estimation of

regression coefficient (B) | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| FIGO stage | 1.873 | 6.510 (1.877,

22.575) | 0.006a |

| KIN17

expression | 1.040 | 2.828 (1.035,

7.732) | 0.043a |

Association between KIN17 expression

and the proliferation, as well as cisplatin sensitivity, of ovarian

cancer cells

To further investigate the effects of KIN17 on EOC,

shRNA-KIN17 was used to silence KIN17 expression, and a stably

transfected SKOV3 cell line was generated. The transfection

efficiency was examined by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3A), RT-qPCR (P<0.05; Fig. 3B) and western blotting (P<0.05;

Fig. 3C and D). As shown in Fig. 3E, from day 4, compared with the

shRNA-Scramble group, the cell proliferation of SKOV3 cells in the

shRNA-KIN17 group was markedly lower (P<0.05), which implied

that KIN17 knockdown could inhibit the proliferation of SKOV3

cells. Fig. 3F shows that between

the concentrations of cisplatin 0.5 to 4 µg/ml, compared with the

shRNA-Scramble group, the cell proliferation of SKOV3 cells in the

shRNA-KIN17 group was markedly lower (P<0.05), which suggested

KIN17 knockdown sensitized SKOV3 cells to cisplatin.

Migration ability of EOC cells is

inhibited by downregulation of KIN17

A trans-well assay was used to detect the migration

ability of EOC cells. As shown in Fig.

3G, cisplatin at 1 µg/ml inhibited the migration ability of

SKOV3 cells. Following treatment with shRNA-KIN17, the number of

cells migrating through the polycarbonate membrane was

significantly decreased in the combine group (Fig. 3G), indicating that KIN17 knockdown

could inhibit the migration ability of EOC cells. Therefore, the

experimental data implied a notable role of KIN17 in the migration

ability of EOC cells.

Discussion

Although the KIN17 protein serves an important role

in human cells, it is not a highly expressed protein in all human

tissues. Normally, KIN17 expression in the majority of normal

tissues is low, while KIN17 upregulation has been detected in

various cancer tissues (27), such

as breast cancer (16), cervical

cancer (17), liver cancer (18) and lung cancer (19). Compared with the normal breast cell

line HS578Bst, the expression levels of KIN17 are upregulated in

MDA-MB-231, SKBr-3, BT474, and MCF-7 cell lines (breast carcinoma)

(16). Moreover, compared with

immortalized epidermal keratinocyte line HaCaT, the expression

levels of KIN17 are upregulated in H1299, K562 (colorectal

carcinoma), PC3 (prostatic carcinoma) and HeLa cell lines (cervical

carcinoma) (28). These results

suggest that KIN17 might be closely associated with the development

of malignancies.

In the present study, the expression levels of KIN17

were demonstrated to be markedly upregulated in EOC tissues

compared with EOC-adjacent tissues, borderline EOC tissues and

normal ovary tissues. The present in vitro experimental

results demonstrated that KIN17 silencing inhibited the

proliferation of EOC cells. These results implied that the

expression levels of KIN17 were associated with the oncogenesis and

development of EOC. Furthermore, advanced stages (stage III+IV),

type II, high grade and high KIN17 expression were identified as

risk factors for OS in patients with EOC based on Kaplan-Meier

univariate analysis. In addition, the study revealed that both

advanced disease stage and high expression levels of KIN17 were

independent risk factors based on Cox multivariate analysis. These

results provided strong clinical evidence that KIN17 may have

prognostic value in patients with EOC. The clinical data

demonstrated that the KIN17 protein was closely associated with the

OS of patients with EOC.

The combination of cytoreductive surgery and

platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard treatment for patients

with EOC (29). Homologous

recombination is one of the important mechanisms of DNA damage

repair and subsequent chemotherapeutic resistance in tumor cells

(30). Therefore, exploring

molecules that could regulate homologous recombination and thus

prevent platinum resistance in EOC is an important line of

research. Previous studies have suggested that KIN17 could induce

chemotherapy resistance in cancer cells by initiating the

homologous recombination signaling pathway, resulting in the poor

prognosis of patients with cancer (14,31–33). The

results of the bioinformatics and clinical analyses demonstrated

that patients with EOC with high KIN17 expression had a poorer

prognosis as compared with the patients with low KIN17 expression,

which suggested that KIN17 could be a prognostic biomarker for EOC.

However, to the best of our knowledge, the mechanisms are still

unclear. Bioinformatics data suggested that high mRNA expression

levels of KIN17 might be associated with cisplatin resistance in

EOC cell lines. Furthermore, the present in vitro analysis

revealed that KIN17 knockdown could increase the sensitivity of EOC

cells to cisplatin, which might be associated with the failure of

the homologous recombination signaling pathway in the cells. These

results imply that patients with EOC with low expression levels of

KIN17 might be more sensitive to cisplatin and have an improved

prognosis.

Migration of EOC cells is markedly related to the

prognosis of patients (34). A

previous study suggested that KIN17 might be a prognostic biomarker

of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), since it serves a key role

in the invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells (19). The effect of KIN17 on cell invasion

has also been observed in cervical cancer (17). In the present study, the clinical

data suggested that patients with EOC with high KIN17 expression

were more likely to suffer from lymph node metastasis. Subsequent

experiments indicated that KIN17 silencing resulted in inhibition

of EOC cell migration in vitro. Furthermore, the

anti-migration effect of cisplatin might be enhanced by KIN17

knockdown in vitro. Therefore, it was hypothesized that EOC

cells in the tissues of patients with low expression levels of

KIN17 may be less likely to migration, leading to an improved

prognosis.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that the

expression levels of KIN17 were increased in EOC. High KIN17

expression may be associated with the oncogenesis and development

of EOC. Additionally, high expression levels of KIN17 were

associated with lymph node metastasis, which might lead to a poor

prognosis. Furthermore, KIN17 knockdown inhibited the proliferation

and migration of EOC cells and sensitized EOC cells to cisplatin

in vitro. Therefore, KIN17 may be an ideal candidate for

therapy and a prognostic biomarker of EOC, which warrants further

exploration.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the

Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission (grant no.

2014G073), the Jilin Province of Department Finance (grant no.

2019SCZT040) and the Jilin Province Science and Technology

Department (grant no. 20200201589JC).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

JC, SZ and LZ conceived and designed the

experiments. YX, YP, SW, WL and HZ performed the experiments. TW,

ZY and YP collected and analyzed the data. JC and SW interpreted

the results and wrote the manuscript. JC, YX and SZ assessed and

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors agree

to be accountable for all aspects of the research and to guarantee

the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

standard guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Second Hospital of Jilin University (approval no. 2018218;

Changchun, China). All patients provided written informed consent

prior to the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I and Oza

AM: Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 393:1240–1253. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser

S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D and Bray F: Cancer

incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major

patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 136:E359–E386. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC and

Ledermann JA: Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 384:1376–1388. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Griffiths RW, Zee YK, Evans S, Mitchell

CL, Kumaran GC, Welch RS, Jayson GC, Clamp AR and Hasan J: Outcomes

after multiple lines of chemotherapy for platinum-resistant

epithelial cancers of the ovary, peritoneum, and fallopian tube.

Int J Gynecol Cancer. 21:58–65. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M,

Karathanasi A, Sadauskaite A, Rassy E and Pavlidis N: Combined

strategies with poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for

the treatment of ovarian cancer: A literature review. Diagnostics

(Basel). 9:872019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Luvero D, Milani A and Ledermann JA:

Treatment options in recurrent ovarian cancer: Latest evidence and

clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 6:229–239. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dasari S and Tchounwou PB: Cisplatin in

cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol.

740:364–378. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang QE, Milum K, Han C, Huang YW, Wani G,

Thomale J and Wani AA: Differential contributory roles of

nucleotide excision and homologous recombination repair for

enhancing cisplatin sensitivity in human ovarian cancer cells. Mol

Cancer. 10:242011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Borst P, Rottenberg S and Jonkers J: How

do real tumors become resistant to cisplatin? Cell Cycle.

7:1353–1359. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Norouzi-Barough L, Sarookhani MR, Sharifi

M, Moghbelinejad S, Jangjoo S and Salehi R: Molecular mechanisms of

drug resistance in ovarian cancer. J Cell Physiol. 233:4546–4562.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Burdova K, Storchova R, Palek M and

Macurek L: WIP1 promotes homologous recombination and modulates

sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Cells. 8:12582019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lord CJ and Ashworth A: The DNA damage

response and cancer therapy. Nature. 481:287–294. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jiang QG, Xiong CF and Lv YX: Kin17

facilitates thyroid cancer cell proliferation, migration, and

invasion by activating p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Mol Cell

Biochem. 476:727–739. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network,

. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature.

474:609–615. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Denis SFB, Miccoli L, Despras E, Frobert

Y, Creminon C and Angulo JF: Ionizing radiation triggers

chromatin-bound kin17 complex formation in human cells. J Biol

Chem. 277:19156–19165. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zeng T, Gao H, Yu P, He H, Ouyang X, Deng

L and Zhang Y: Up-regulation of kin17 is essential for

proliferation of breast cancer. PLoS One. 6:e253432011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang Y, Gao H, Gao X, Huang S, Wu K, Yu

X, Yuan K and Zeng T: Elevated expression of Kin17 in cervical

cancer and its association with cancer cell proliferation and

invasion. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 27:628–633. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kou WZ, Xu SL, Wang Y, Wang LW, Wang L,

Chai XY and Hua QL: Expression of Kin17 promotes the proliferation

of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in

vivo. Oncol Lett. 8:1190–1194. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang Y, Huang S, Gao H, Wu K, Ouyang X,

Zhu Z, Yu X and Zeng T: Upregulation of KIN17 is associated with

non-small cell lung cancer invasiveness. Oncol Lett. 13:2274–2280.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lu KH, Patterson AP, Wang L, Marquez RT,

Atkinson EN, Baggerly KA, Ramoth LR, Rosen DG, Liu J, Hellstrom I,

et al: Selection of potential markers for epithelial ovarian cancer

with gene expression arrays and recursive descent partition

analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 10:3291–3300. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Anglesio MS, Arnold JM, George J, Tinker

AV, Tothill R, Waddell N, Simms L, Locandro B, Fereday S,

Traficante N, et al: Mutation of ERBB2 provides a novel alternative

mechanism for the ubiquitous activation of RAS-MAPK in ovarian

serous low malignant potential tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 6:1678–1690.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Györffy B, Surowiak P, Kiesslich O,

Denkert C, Schäfer R, Dietel M and Lage H: Gene expression

profiling of 30 cancer cell lines predicts resistance towards 11

anticancer drugs at clinically achieved concentrations. Int J

Cancer. 118:1699–1712. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gyorffy B, Lánczky A and Szállási Z:

Implementing an online tool for genome-wide validation of

survival-associated biomarkers in ovarian-cancer using microarray

data from 1287 patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 19:197–208. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn

MA, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, Ngan HY, Pecorelli S and Beller U:

Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th annual report on the results of

treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 95 (Suppl

1):S161–S192. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kong D, Chen J, Sun X, Lin Y, Du Y, Huang

D, Cheng H, He P, Yang L, Wu S, et al: GRIM-19 over-expression

represses the proliferation and invasion of orthotopically

implanted hepatocarcinoma tumors associated with downregulation of

Stat3 signaling. Biosci Trends. 13:342–350. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kannouche P, Mauffrey P, Pinon-Lataillade

G, Mattei MG, Sarasin A, Daya-Grosjean L and Angulo JF: Molecular

cloning and characterization of the human KIN17 cDNA encoding a

component of the UVC response that is conserved among metazoans.

Carcinogenesis. 21:1701–1710. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Despras E, Miccoli L, Créminon C,

Rouillard D, Angulo JF and Biard DS: Depletion of KIN17, a human

DNA replication protein, increases the radiosensitivity of RKO

cells. Radiat Res. 159:748–758. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

2:160622016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Haynes B, Saadat N, Myung B and Shekhar

MP: Crosstalk between translesion synthesis, Fanconi anemia

network, and homologous recombination repair pathways in

interstrand DNA crosslink repair and development of

chemoresistance. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 763:258–266. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Prat J: New insights into ovarian cancer

pathology. Ann Oncol. 23 (Suppl 10):x111–x117. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Doufekas K and Olaitan A: Clinical

epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer in the UK. Int J Womens

Health. 6:537–545. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen H, Lisby M and Symington LS: RPA

coordinates DNA end resection and prevents formation of DNA

hairpins. Mol Cell. 50:589–600. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xue Z, Zhu X and Teng Y: Long non-coding

RNA CASC2 inhibits progression and predicts favorable prognosis in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Med Rep. 18:5173–5181.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|