Introduction

According to the Global Cancer Observatory,

>2,200,000 new cases of lung cancer were registered in 2020 and

the number of deaths was ~1,800,000, showcasing that lung cancer is

an important disease endangering health worldwide. Lung cancer is

the leading cause of cancer morbidity and mortality in males. Among

females, the incidence of lung cancer is third only to breast

cancer and colorectal cancer, whereas the mortality rate is second

after breast cancer (1). Non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for ~85% of all cases of lung

cancer. Due to the inconspicuous symptoms of NSCLC, >55% of

patients with NSCLC have already progressed to an advanced stage

when they are diagnosed, with local spread or distant metastasis

and poor prognosis (2,3).

For the treatment of NSCLC, radical surgery is the

preferred option. However, drugs and radiotherapy become

particularly important for patients with advanced NSCLC who cannot

be treated with surgery (4).

Previously, carboplatin or cisplatin combined with gemcitabine,

vinorelbine or paclitaxel were commonly used in the clinic

(5). However, in recent years,

drastic changes have taken place in the treatment of advanced

NSCLC. With the rapidly advancing knowledge of tumor pathogenesis

and the increasing number of studies that have been dedicated to

investigating this phenomenon, molecular targeted therapy has

become a research ‘hotspot’ (6,7). At

present, the drugs that have been indicated to be effective as

first-line therapies in targeted therapy research include erlotinib

(8) and gefitinib (9); certain other drugs, such as

osimertinib (10), have also been

indicated to be efficient as secondline treatments. However, to the

best of our knowledge, limited research has been performed to

investigate drug selection after secondline treatment and docetaxel

combined with cisplatin is frequently used in the clinic at present

(11,12).

Anlotinib is a novel multitarget tyrosine kinase

inhibitor (TKI), which is able to inhibit both tumor angiogenesis

and signal transduction pathways associated with proliferation

(13). The main mechanism may be

inhibition of activation of VEGFR2, PDGFRβ and FGFR1 and downstream

ERK signal transduction. In 2018, Han et al (14) demonstrated the effectiveness of

anlotinib as a third-line treatment for advanced NSCLC through a

multicenter randomized controlled study. However, this study only

compared with a placebo and not with other drugs. After anlotinib

became commercially available in China in May 2018, additional

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared the efficacy of

anlotinib with that of other drugs. In order to explore the most

suitable choice of drugs for the third-line treatment of patients

with advanced NSCLC and to help formulate a better treatment

strategy for NSCLC, the present study comprises a systematic review

and metaanalysis to explore the efficacy and safety of third-line

treatment with anlotinib for patients with advanced NSCLC. The

findings in the present study were reported according to the

‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and

Meta-Analyses’ (15).

Materials and methods

Data sources and searches

Studies were searched from PubMed, Web of Science,

the Cochrane Library (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/) and several Chinese

databases, including Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure

(CNKI; http://www.cnki.net/), WangFang data

(https://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/) and VIP

(https://www.cqvip.com/), up to February 2022.

Searches were based on combinations of the following index terms:

‘anlotinib’, ‘tyrosine kinase inhibitor’, ‘advanced non-small cell

lung cancer’ and ‘third line therapy’. At the same time, the

references included within each individual study were searched to

supplement the relevant information.

Retrieved articles were included in the present

study as long as the following criteria were satisfied: i) The

study was an RCT; ii) patients with refractory advanced NSCLC that

had been confirmed by pathology or cytology had been treated

previously with two or more chemotherapeutic drugs; iii) the

patient was over 18 years of age; iv) there were no restrictions on

the disclosure of other patient information, such as the sex of the

patient; v) the anlotinib group had been treated with anlotinib;

vi) the control group was treated with either a placebo or other

drugs excluding anlotinib; and vii) the results included at least

one outcome out of progression-free survival (PFS), overall

survival (OS), disease control rate (DCR), objective response rate

(ORR), Karnofsky performance status (KPS) or adverse events

(AEs).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Studies

without original research data; ii) the study was published in a

language other than English or Chinese; and iii) publications

containing the same data as those published elsewhere.

Data extraction and quality

assessment

A total of two researchers (BWZ and YXZ)

independently screened the literature, extracted the data and

cross-checked them. If any differences were identified, these were

settled through discussion or by negotiation with a third party.

When screening articles, the title was read first and after

excluding obviously irrelevant articles, the abstract and full text

were subsequently read to determine whether or not to include them.

If deemed to be necessary, the author of the original research

study was contacted by e-mail or telephone to obtain any

information that was unclear but important for the present study.

The data extraction contents included the following: Basic

information included in the article, i.e., the research topic,

first author, journal wherein the data had been published; baseline

characteristics and intervention measures of research subjects; key

elements of bias risk assessment; and the relevant outcome

indicators and result measurement data.

Two researchers (BWZ and YXZ) also independently

evaluated the bias risk of inclusion in the study and cross-checked

the results. The bias risk assessment that was adopted was the RCT

bias risk assessment tool recommended by the Cochrane Manual 5.1.0

(16).

Data analysis

RevMan 5.3 software (2014; Cochrane Cooperation

Center) was used for the statistical analysis. The survival data

were extracted from Kaplan-Meier curves using Engauge digitizer 4.1

software (17). The hazard ratio

(HR) of PFS and OS, and the risk ratio (RR) of the DCR, ORR and AEs

were calculated by RevMan5.3. The mean differences (MDs) of KPS

were also calculated by RevMan5.3. Q-statistics were used to

evaluate the statistical heterogeneity among experiments. If the

P-value of the Q-statistics was indicated to be <0.1 or

I2 was >50%, this was considered to indicate that the

heterogeneity among studies was statistically significant. If there

was significant heterogeneity, the data were analyzed according to

the random-effects model; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was

adopted (18).

According to the intervention measures of the

control group and the basic information of the patients, subgroup

analysis was conducted to reduce the level of heterogeneity. For

the outcomes of >10 articles, a funnel chart was used to test

the publication bias. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. All P-values were bilateral

and the bilateral coverage rate of the CI was 95%.

Results

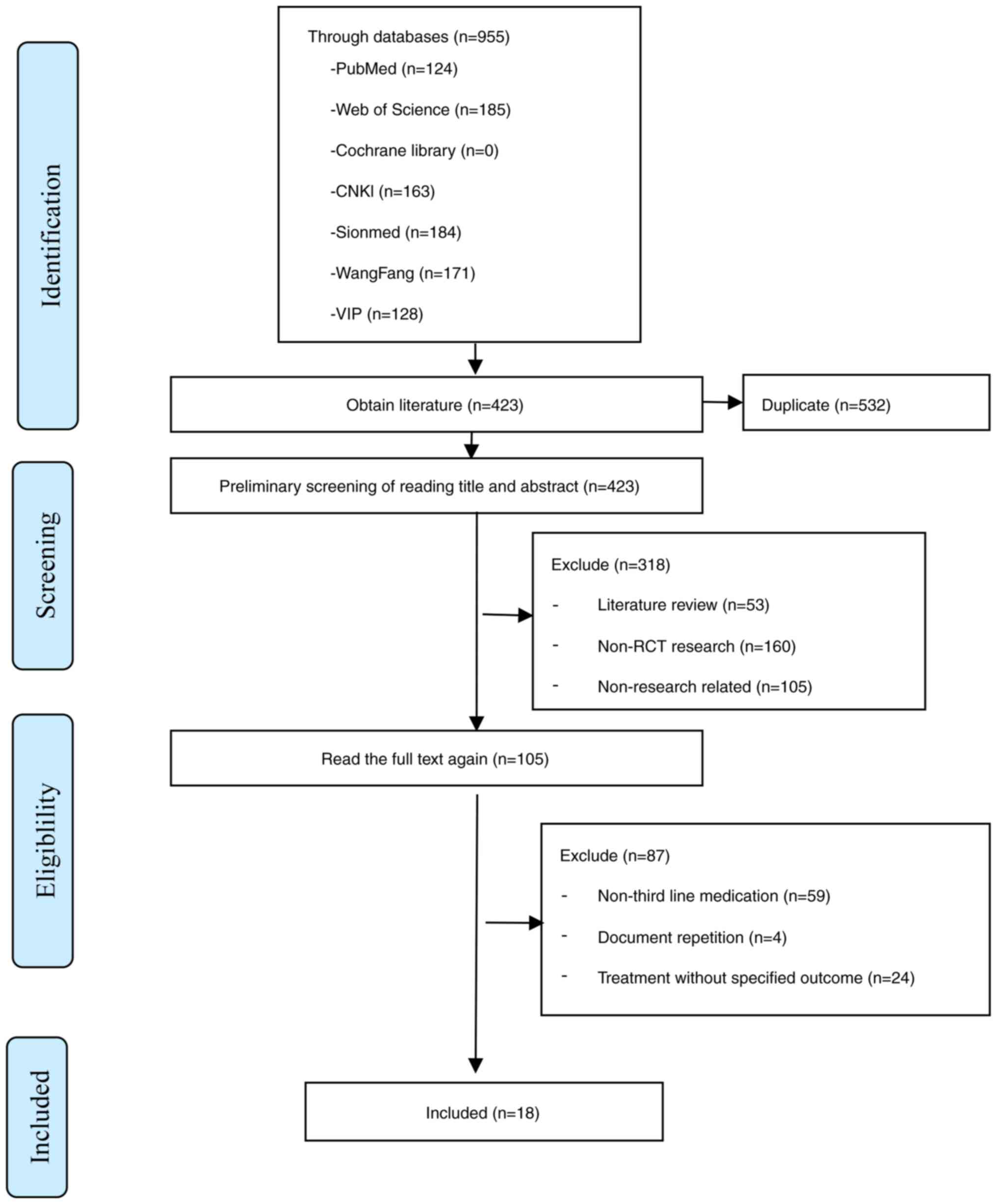

Study selection

In the present study, a total of 955 articles were

searched in various databases, as detailed above, and after

screening, a total of 18 RCTs were included in the study (14,19–35).

A flow chart of the study selection process is presented in

Fig. 1.

Study characteristics and quality

assessments

A total of 1,658 patients were included in the

present study, comprising 913 patients in the anlotinib group (550

male and 363 female patients) and 745 patients in the control group

(479 male and 266 female patients). The average age of the patients

in each study ranged from 51.30 to 66.50 years. In the present

study, the anlotinib groups of each study were treated with only

anlotinib (12 mg daily for 21 days). Each study control group used

different measures, such as a placebo or supportive treatment. The

details are presented in Table

I.

| Table I.Basic characteristics of included

studies. |

Table I.

Basic characteristics of included

studies.

|

| Male cases | Age, years | Intervention

measure |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Author and year

(trial number) | T (%) | C (%) | T | C | T | C | Outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Chen, et al,

2021 | 28 (62.2) | 27 (60.0) | 54.28±5.10 | 54.34±5.06 |

Anlotiniba | Gemcitabine +

cisplatinb | DCR, ORR, KPS,

AEs | (19) |

| Dai, et al,

2019 | 14 (70.0) | 12 (60.0) | - | - |

Anlotiniba | Support

therapyc | PFS, OS, DCR,

ORR | (20) |

| Feng, et al,

2020 | 38 (63.3) | 40 (66.7) | 65.73±5.23 | 64.36±4.84 |

Anlotiniba | Routine

chemotherapyd | DCR, ORR, AEs | (21) |

| Gou, et al,

2020 | 14 (38.3) | 13 (37.1) | 62.72±14.23 | 65.68±16.86 |

Anlotiniba | Pemetrexed +

cisplatine | DCR, ORR, KPS,

AEs | (22) |

| Han, et al,

2021 | 26 (57.8) | 25 (55.6) | 56.93±4.23 | 56.58±4.11 |

Anlotiniba | Gemcitabine +

cisplatinb | DCR, ORR, AEs | (23) |

| Han, et al,

2018 (ALTER0302) | 26 (43.3) | 33 (57.9) | 55.2±10.0 | 55.5±9.1 |

Anlotiniba |

Placebof | PFS, OS, DCR, ORR,

AEs | (24) |

| Han, et al,

2018 (ALTER0303) | 188 (64.0) | 97 (67.8) | 57.9±9.1 | 56.8±9.1 |

Anlotiniba |

Placebof | PFS, OS, DCR, ORR,

AEs | (14) |

| Huang 2020 | 20 (57.1) | 21 (60.0) | 66.7±5.3 | 66.3±5.7 |

Anlotiniba | Routine

chemotherapyd | DCR, ORR, AEs | (25) |

| Kong, et al,

2020 | 15 (68.2) | 14 (63.6) | 57.47±8.13 | 55.38±10.44 |

Anlotiniba |

Placebof | DCR, ORR, KPS | (26) |

| Liu, et al,

2020 | 33 (66.0) | 31 (62.0) | 60.94±10.74 | 60.74±10.98 |

Anlotiniba | Routine

chemotherapyd | DCR, ORR, KPS,

AEs | (27) |

| Luo and Yu,

2021 | 12 (52.2) | 13 (56.5) | 56.43±3.82 | 55.36±4.36 |

Anlotiniba | Gemcitabine+

cisplatinb | DCR, ORR | (28) |

| Si, et al,

2019 | 9 (56.3) | 4 (50.0) | 57.5 | 62.5 |

Anlotiniba |

Placebof | PFS, OS, DCR, ORR,

AEs | (29) |

| Sun, 2021 | 13 (54.2) | 14 (58.3) | 51.48±1.78 | 51.51±1.84 |

Anlotiniba | Gemcitabine+

cisplatinb | ORR, AEs | (30) |

| Tian, 2021 | 30 (61.2) | 28 (62.2) | 50.64±10.36 | 52.00±11.06 |

Anlotiniba | Gemcitabine +

vinorelbineg | DCR, ORR, KPS,

AEs | (31) |

| Wang, 2020 | 15 (68.2) | 16 (72.7) | 66.3±1.7 | 66.5±1.5 |

Anlotiniba |

Placebof | AEs | (32) |

| Yang, 2019 | 23 (63.9) | 9 (50.0) | - | - |

Anlotiniba |

Placebof | PFS, OS, DCR, ORR,

AEs | (33) |

| Yu and Liu,

2021 | 24 (60.0) | 24 (60.0) | 56.6±9.8 | 56.5±9.6 |

Anlotiniba | Support

therapyc | DCR, ORR, AEs | (34) |

| Zhu, 2021 | 22 (64.7) | 23 (67.6) | 65.38±5.81 | 65.47±5.84 |

Anlotiniba | Routine

chemotherapyd | DCR, ORR, AEs | (35) |

A total of 10 studies were based on the method of

random grouping (14,19–24,29,31,34),

whereas two studies had reported the methods of allocation

concealment (14,24). Furthermore, five articles

explicitly used doubleblinding (14,24,26,29,33),

whereas only two articles had missing data (24,29).

None of the studies featured selective reporting. The results are

presented in Fig. 2.

Effectiveness analysis results

PFS

A total of five studies described the PFS (14,20,24,29,33).

The interstudy heterogeneity was low with I2=27%, and

analysis was thus performed using the fixed-effects model. The

results indicated that there was a significant difference in PFS

between the anlotinib group and the control group (HR=0.33; 95% CI:

0.28-0.37; P<0.00001; Fig. 3).

In addition, two studies performed subgroup analyses according to

the basic characteristics of patients (14,24)

and the results indicated that the differences between the

anlotinib group and the control group were not associated with

basic demographic characteristics, such as age and sex. Significant

differences in PFS comparing between the anlotinib group and the

control group were identified when considering patients in the

categories of <60 years or >60 years of age, having a history

or no history of smoking, having a history or no history of

receiving radiotherapy, benefiting or not benefiting from epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR)-TKI treatment, and having or lacking

the EGFR gene mutation.

OS

A total of five studies reported on OS (14,20,24,29,33).

The interstudy heterogeneity was low I2=0%, so that

analysis was performed using the fixed-effects model. The results

suggested that there was a significant difference in OS between the

anlotinib group and the control group (HR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.81;

P<0.00001; Fig. 4). A study

conducted subgroup analysis based on patients’ age, gender, tissue

type, smoking history and other information to determine whether

different disease states have an impact on the efficacy of

anlotinib (14). The results

indicated an improvement of OS after treatment with anlotinib in

all subgroups.

DCR

A total of 16 studies reported on the DCR (14,19–29,31,33–35).

The heterogeneity between studies was I2=82%, so that

analysis was performed using the random-effects model. The results

suggested that the DCR in the anlotinib group was significantly

higher compared with that in the control group (RR=1.51; 95% CI,

1.27-1.79; P<0.00001; Fig. 5).

Subgroup analysis was performed according to the measures used in

the control group. After grouping, the I2 of the

heterogeneity test in each group was 0, indicating that the control

measure may be one of the factors leading to the heterogeneity

among DCR studies. Subgroup analysis indicated that the anlotinib

group was significantly different from the placebo, routine

chemotherapy, gemcitabine + cisplatin, supportive treatment and

gemcitabine + vinorelbine groups. However, no significant

difference was observed between the anlotinib group and the

pemetrexed + cisplatin group. The results are presented in Table II.

| Table II.Subgroup analysis of the disease

control rate of the third-line treatment of advanced non-small cell

lung cancer in the anlotinib group and control group. |

Table II.

Subgroup analysis of the disease

control rate of the third-line treatment of advanced non-small cell

lung cancer in the anlotinib group and control group.

|

|

|

| Heterogeneity |

| Meta-analysis

results |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Control

measure | Number of studies

(Refs.) | Cases | P-value | I2

value | Model | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Placebo | 5 (14,24,26,29,33) | 428/248 | 0.63 | 0 | Fixed | 2.17

(1.83-2.56) | <0.001 |

| Routine

chemotherapy | 4 (21,25,28,35) | 179/179 | 0.78 | 0 | Fixed | 1.23

(1.10-1.36) | <0.001 |

| Gemcitabine +

cisplatin | 3 (19,23,27) | 113/113 | 0.55 | 0 | Fixed | 1.16

(1.04-1.30) | 0.007 |

| Support

therapy | 2 (20,34) | 60/60 | 0.55 | 0 | Fixed | 2.39

(1.57-3.63) | <0.001 |

| Pemetrexed +

cisplatin | 1 (22) | 36/36 | - | - | - | 1.23

(0.97-1.55) | 0.08 |

| Gemcitabine +

vinorelbine | 1 (31) | 49/45 | - | - | - | 2.57

(1.01-6.57) | 0.05 |

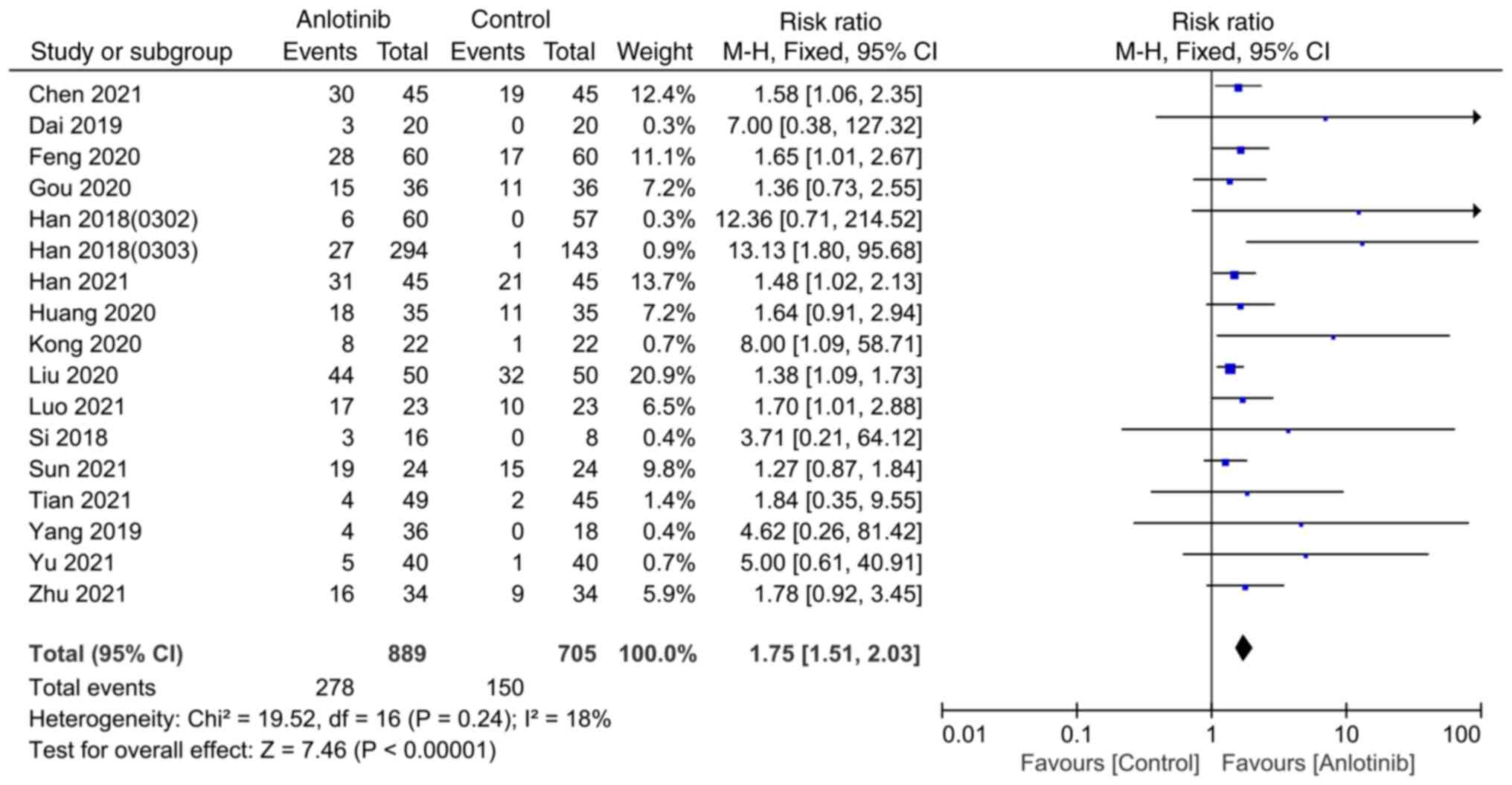

ORR

A total of 17 studies reported the ORR (14,19–31,33–35).

The heterogeneity among studies was I2=18%, and the

fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The results indicated

that the ORR of the anlotinib group was significantly higher

compared with that of the control group (RR=1.75; 95% CI,

1.51-2.03; P<0.00001; Fig. 6).

Subgroup analysis was performed according to the measures used by

the control groups of each study. After grouping, the heterogeneity

test results of each group were low (I2=0), indicating

that the control measures may be one of the factors leading to the

heterogeneity of the ORR studies. Subgroup analysis suggested that

there were significant differences between the anlotinib group and

the placebo, conventional chemotherapy, gemcitabine + cisplatin and

supportive treatment groups, although no statistically significant

differences were obtained between the anlotinib group and the

pemetrexed + cisplatin group or the gemcitabine + vinorelbine

group. The results are presented in Table III.

| Table III.Subgroup analysis of the objective

response rate of the third-line treatment of advanced non-small

cell lung cancer in anlotinib group and control group. |

Table III.

Subgroup analysis of the objective

response rate of the third-line treatment of advanced non-small

cell lung cancer in anlotinib group and control group.

|

|

|

| Heterogeneity |

| Meta analysis

results |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Control

measure | Number of studies

(Refs.) | Cases | P-value | I2

value | Model | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Placebo | 5 (14,24,26,29,33) | 428/248 | 0.94 | 0 | Fixed | 8.98

(3.06-26.38) | <0.001 |

| Routine

chemotherapy | 4 (21,25,28,35) | 179/179 | 0.76 | 0 | Fixed | 1.54

(1.25-1.89) | <0.001 |

| Gemcitabine +

cisplatin | 4 (19,23,27,30) | 137/137 | 0.79 | 0 | Fixed | 1.49

(1.22-1.83) | <0.001 |

| Support

therapy | 2 (20,34) | 60/60 | 0.85 | 0 | Fixed | 5.67

(1.04-31.00) | <0.05 |

| Pemetrexed +

cisplatin | 1 (22) | 36/36 | - | - | - | 1.36

(0.73-2.55) | 0.33 |

| Gemcitabine +

vinorelbine | 1 (31) | 49/45 | - | - | - | 1.84

(0.35-9.55) | 0.47 |

KPS

A total of five studies reported the KPS (19,22,26,27,31).

The heterogeneity among studies was I2=87%, and thus,

data were analyzed using the random-effects model. The results

suggested that the KPS of the anlotinib group was significantly

higher compared with that of the control group (MD=9.85; 95% CI,

6.26-13.43; P<0.00001; Fig. 7).

However, due to the small number of studies and the lack of

subgroup information in each study, no further analysis was

possible.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed for PFS, OS, DCR,

ORR and KPS. For this, the results of each of the 18 articles were

excluded at a time and it was observed whether the pooled results

had changed. It was found that exclusion of none of the individual

studies affected the final result (data not shown).

Safety

A total of 13 articles reported the incidence of AEs

in the anlotinib group and the control group in detail (14,19,21–25,27,29–33).

The major AEs were included in the pooled analysis and there were

eight studies on hypertension. The research on hypertension,

hand-foot syndrome, fatigue, oral mucositis and

hypertriglyceridemia had a high level of heterogeneity, so the

random-effects model was used. For the other studies, the

fixed-effects model was used. It was observed the anlotinib group

was significantly higher than the control group in terms of seven

AEs, namely hypertension, hand-foot syndrome, hemoptysis,

proteinuria, cough, diarrhea and hypercholesterolemia, whereas no

statistically significant differences were identified for the other

AEs, as indicated in Table

IV.

| Table IV.AEs in the anlotinib group and

control group with third-line treatment of advanced non-small cell

lung cancer. |

Table IV.

AEs in the anlotinib group and

control group with third-line treatment of advanced non-small cell

lung cancer.

|

|

|

| Heterogeneity |

| Meta-analysis

results |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| AEs | Number of studies

(Refs.) | Cases | P-value | I2

value | Model | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Hypertension | 8 | 596/512 | <0.001 | 80 | Random | 3.14

(1.43-6.90) | 0.004 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 4 (14,24,29,33) | 406/226 | 0.09 | 54 | Random | 5.74

(2.89-11.40) | <0.001 |

| Other

drugs | 4 (19,21,24,31) | 190/186 | 0.11 | 51 | Random | 1.42

(0.60-3.39) | 0.43 |

| Hand-foot

syndrome | 7 | 551/367 | 0.002 | 71 | Random | 3.07

(1.23-7.64) | 0.02 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 4 (14,24,29,33) | 406/226 | 0.60 | 0 | Fixed | 5.08

(3.19-8.08) | <0.001 |

| Other

drugs | 3 (19,22,31) | 145/141 | 0.02 | 76 | Random | 1.50

(0.21-10.50) | 0.68 |

| Hemoptysis | 7 | 536/370 | 0.41 | 2 | Fixed | 1.81

(1.23-2.66) | 0.003 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 4 (14,28,33,34) | 392/230 | 0.73 | 0 | Fixed | 2.41

(1.46-3.96) | <0.001 |

| Other

drugs | 3 (21,25,31) | 144/140 | 0.77 | 0 | Fixed | 0.99

(0.52-1.88) | 0.98 |

| Proteinuria | 6 | 502/322 | 0.85 | 0 | Fixed | 2.15

(1.48-3.11) | <0.001 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 4 (14,24,29,33) | 406/226 | 0.78 | 0 | Fixed | 2.21

(1.47-3.30) | <0.001 |

| Other

drugs | 2 (21,22) | 96/96 | 0.59 | 0 | Fixed | 1.83

(0.71-4.76) | 0.21 |

| Nausea and

vomiting | 6 | 240/229 | 0.56 | 0 | Fixed | 0.76

(0.48-1.18) | 0.22 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 2 (24,29) | 76/65 | 0.60 | 0 | Fixed | 0.78

(0.42-1.42) | 0.41 |

| Other

drugs | 4 (19,23,27,30) | 164/164 | 0.30 | 18 | Fixed | 0.74

(0.38-1.42) | 0.36 |

| Fatigue | 5 | 466/304 | 0.002 | 76 | Random | 0.87

(0.56-1.37) | 0.55 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 2 (14,24) | 354/200 | 0.12 | 60 | Random | 1.44

(0.90-2.29) | 0.13 |

| Other

drugs | 3 (21,22,30) | 112/104 | 0.51 | 0 | Fixed | 0.73

(0.52-1.04) | 0.07 |

| Oral Mucositis | 5 | 479/313 | 0.004 | 74 | Random | 3.37

(0.94-12.17) | 0.06 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.87 | 0 | Fixed | 8.64

(3.58-20.84) | <0.001 |

| Other

drugs | 2 (21,31) | 109/105 | 0.21 | 37 | Fixed | 1.13

(0.55-2.34) | 0.74 |

| Anaemia | 4 | 150/132 | 0.75 | 0 | Fixed | 0.47

(0.22-1.02) | 0.75 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 1 (33) | 36/18 | - | - | - | 0.67

(0.27-1.63) | 0.37 |

| Other

drugs | 3 (19,23,30) | 114/114 | 0.87 | 0 | Fixed | 0.29

(0.07-1.17) | 0.08 |

| Cough | 4 | 411/257 | 0.23 | 30 | Fixed | 1.56

(1.19-2.04) | 0.001 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 3 (14,24,32) | 376/222 | 0.14 | 49 | Fixed | 1.61

(1.21-2.13) | 0.001 |

| Other

drugs | 1 (25) | 35/35 | - | - | - | 1.14

(0.46-2.81) | 0.77 |

| Diarrhea | 3 | 370/208 | 0.48 | 0 | Fixed | 2.52

(1.72-3.69) | <0.001 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.48 | 0 | Fixed | 2.52

(1.72-3.69) | <0.001 |

|

Hypercholesterolemia | 3 | 370/208 | 0.75 | 0 | Fixed | 3.14

(2.12-4.66) | <0.001 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.75 | 0 | Fixed | 3.14

(2.12-4.66) | <0.001 |

|

Hypertriglyceridemia | 3 | 370/208 | 0.09 | 58 | Random | 1.95

(0.91-4.17) | 0.09 |

| Placebo

or support therapy | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.09 | 58 | Random | 1.95

(0.91-4.17) | 0.09 |

The AEs were analyzed in subgroups and divided into

groups according to the control measures, with placebo or

supportive treatment as one group and other drugs as the other

group. It was determined that the anlotinib group had a

significantly higher incidence of hypertension, hand-foot syndrome,

hemoptysis, proteinuria, oral mucositis, diarrhea and

hypertriglyceridemia than the placebo or supportive treatment

group. However, no significant differences in each outcome index

were identified between the anlotinib group and other drug groups,

as indicated in Table IV.

In addition, four studies reported on the occurrence

of AEs of grade 3 or above (14,24,29,31).

The results indicated that there was no significant difference

between the anlotinib group and control group in terms of

hypertension (RR=4.68, 95% CI, 0.44-49.58; P=0.20), hemoptysis

(RR=1.51, 95% CI, 0.464.91; P=0.49) and oral mucositis (RR=1.26,

95% CI, 0.29-5.41; P=0.76). However, the anlotinib group had a

significantly higher incidence of hand-foot syndrome than the

control group (RR=5.28, 95% CI, 1.18-23.59; P=0.03). Among the four

studies on AEs, three were placebo studies and one used gemcitabine

+ vinorelbine. Subgroup analysis was conducted according to the

control measures. The results indicated that the incidence of grade

3 or above AEs in the anlotinib group was significantly higher than

compared with that in the placebo group with respect to

hypertension and hand-foot syndrome, although no significant

differences were observed when comparing between the anlotinib

group and the gemcitabine + vinorelbine group, as indicated in

Table V.

| Table V.Grade 3 or above AEs in the anlotinib

group and control group with third-line treatment of advanced

non-small cell lung cancer. |

Table V.

Grade 3 or above AEs in the anlotinib

group and control group with third-line treatment of advanced

non-small cell lung cancer.

|

|

|

| Heterogeneity |

| Meta-analysis

results |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| AEs | Number of studies

(Refs.) | Cases | P-value | I2

value | Model | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Hypertension | 4 | 419/253 | 0.02 | 68 | Random | 4.68

(0.44-49.58) | 0.20 |

|

Placebo | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.52 | 0 | Fixed | 19.59

(3.76-102.20) | <0.001 |

|

Gemcitabine + Vinorelbine | 1 (31) | 49/45 | - | - | - | 0.31

(0.03-2.84) | 0.30 |

| Hemoptysis | 4 | 419/253 | 0.55 | 0 | Fixed | 1.51

(0.46-4.91) | 0.49 |

|

Placebo | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.86 | 0 | Fixed | 2.17

(0.53-8.10) | 0.30 |

|

Gemcitabine + Vinorelbine | 1 (31) | 49/45 | - | - | - | 0.31

(0.01-7.34) | 0.47 |

| Oral mucositis | 4 | 419/253 | 0.56 | 0 | Fixed | 1.26

(0.29-5.41) | 0.76 |

|

Placebo | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.72 | 0 | Fixed | 2.52

(0.30-21.10) | 0.40 |

|

Gemcitabine + Vinorelbine | 1 (31) | 49/45 | - | - | - | 0.46

(0.04-4.89) | 0.52 |

| Hand-foot

syndrome | 4 | 419/253 | 0.80 | 0 | Fixed | 5.28

(1.18-23.59) | 0.03 |

|

Placebo | 3 (14,24,29) | 370/208 | 0.63 | 0 | Fixed | 5.99

(1.10-32.70) | 0.04 |

|

Gemcitabine + Vinorelbine | 1 (31) | 49/45 | - | - | - | 2.76

(0.12-66.07) | 0.53 |

Publication bias

Drawing funnel graphs based on the DCR and ORR

revealed that the two plots were left- and right-asymmetrical, as

indicated in Figs. 8 and 9. This suggested that there may have been

a certain amount of publication bias.

Discussion

At present, drugs available for the thirdline

treatment of advanced NSCLC are limited. The first-line and

second-line treatment schemes for patients with NSCLC with positive

or negative driver gene mutations have been well-defined, but only

a small number of drugs are in clinical use for the third-line

treatment and the standardized treatment has not been perfected

(36). Previous studies have used

monoclonal antibodies or macromolecular vascular targeting drugs,

such as bevacizumab, to treat advanced NSCLC, although their safety

standards did not reach a satisfactory level (37). At present, pemetrexed or docetaxel

is recommended for patients with the negative driver genes of

non-squamous cell carcinoma. Anlotinib was approved for use in

China in May 2018 (38).

Anlotinib is a novel type of multitarget

small-molecule drug with antiangiogenesis and anti-tumor properties

that is able to inhibit tumor angiogenesis and cell proliferation

by selectively inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

receptor, fibroblast growth factor receptor and plateletderived

growth factor receptor (39). In

addition to its usefulness for NSCLC, anlotinib monotherapy has

also achieved good results for a variety of other solid tumors,

including liver cancer (40).

Through systematic evaluation and meta-analysis, the

present study indicated that, compared with the control group, the

third-line treatment of advanced NSCLC with anlotinib was able to

significantly improve the DCR, ORR and KPS, and significantly

prolong PFS and OS. Subgroup analysis according to the treatment

measures of the control group indicated that the DCR and ORR of the

anlotinib group were significantly higher compared with those in

the placebo, supportive treatment, conventional chemotherapy and

gemcitabine + cisplatin groups. However, compared with the

pemetrexed + cisplatin and gemcitabine + vinorelbine groups, the

DCR and ORR values failed to exhibit significant differences,

although, given the relative sparsity of published studies in this

area, it is not possible at present to draw any firm conclusions in

relation to this. Subgroup analysis for PFS indicated that the

difference between the anlotinib group and the control group was

not associated with baseline characteristics, such as the age and

sex of the patients. In conclusion, compared with the placebo or

supportive treatment groups, the curative effect of anlotinib on

advanced NSCLC was appreciable. Compared with treatment with a

combination of gemcitabine + cisplatin and therapy with other drugs

currently used for third-line treatment, anlotinib also had

advantages in terms of effectiveness.

In addition to the abovementioned studies included

in the meta-analysis, several other studies have reported on other

indicators with regard to evaluating their curative effects. Due to

the different measurement methods and the small number of studies,

however, it was not suitable for these studies to be included in

the combined analysis, although several of these studies will now

be briefly described. Two studies reported on the changes in tumor

marker concentration in patients prior to and after intervention

(21,27). The results suggested that, after

treatment, the serum carcinoembryonic antigen and

cytokeratin-19-fragment in the anlotinib group were significantly

lower compared with those in the control group. Another study

reported on the changes in lung function (27), which suggested that the forced

expiratory volume in one second and 6-minute walking distance in

the anlotinib group were significantly higher compared with those

in the control group. A further study discussed the analysis of

blood gas (28) and revealed that

the partial pressure of oxygen and oxygen saturation of the

arterial blood in the anlotinib group were higher compared with

those in the control group, whereas the partial pressure of

CO2 was lower than that in the control group, and this

difference was statistically significant. The above findings also

reflect different aspects of the effectiveness of anlotinib in

improving the physical condition of patients with advanced

NSCLC.

In terms of safety, the present study suggested that

there were significant differences between the anlotinib group and

the control group with respect to hypertension, hand-foot syndrome,

hemoptysis, proteinuria, cough, diarrhea and hypercholesterolemia,

but no statistical differences between the two groups were

identified for the remaining five adverse reactions, including

nausea and vomiting, fatigue, mucositis, anaemia and

hypertriglyceridemia. This finding was not consistent with those of

a previous study by Yu et al (41), presumably because it included three

trials in which the control group was either a placebo or

supportive treatment. However, among the 18 studies included in the

present study, a large proportion of the control groups used other

drugs for treatment, and other therapeutic drugs also caused AEs.

According to the above discussion, the present study suggests that,

compared with other drugs currently used for thirdline treatment,

anlotinib does not exhibit any safety deficiency.

Among the 18 articles included in the present study,

the AEs of interest were hypertension, nausea and vomiting,

hand-foot syndrome and hemoptysis. Nausea is a common

gastrointestinal reaction, which may be caused by drugs directly

stimulating the gastric mucosa or by metabolic factors. It is the

cardiovascular AE that is most commonly associated with

hypertension VEGF pathway inhibitors, a phenomenon that may be

linked to the endothelial dysfunction and the reduction in nitric

oxide release caused by drugs (42). Hemoptysis is an important AE of

anlotinib, which may be associated with its inhibition of the VEGF

receptor, thrombocytopenia and increased bleeding risk. Hand-foot

syndrome is mainly characterized by abnormal sensation, dullness or

numbness of hands and feet, and blisters, ulcers or pain may also

occur in severe cases. This may be associated with anlotinib acting

on the signaling pathway of vascular repair in the compressed parts

of hands and feet (43).

A total of four studies reported on the occurrence

of high-level AEs and the results suggested that there was a

significant difference between the anlotinib group and the control

group in hypertension and handfoot syndrome. Si et al

(29) reported in detail the

treatment of AEs after they occurred; hand-foot syndrome and oral

mucositis were obviously relieved after anlotinib was administered

at a reduced dose of 10 mg, once a day, and other AEs were also

well improved after symptomatic treatment. No treatment-associated

deaths were reported in either study. It may be indicated that AEs

associated with anlotinib are tolerable.

The advantages of the present study are as follows:

i) There were 18 RCTs included in this study, and the results

obtained are reliable; ii) subgroup analysis was carried out

according to the measures of the control group, and the therapeutic

effects and safety of anlotinib were compared with those of

different control measures; and iii) the effectiveness of this

study was evaluated by OS and four other indicators, with special

attention paid to high-level AEs when evaluating safety, and the

evaluation was therefore more comprehensive. The limitations of

this study were as follows: i) The time to market is short and the

patients were all Chinese, so it is impossible to assess the

influence of treatment with anlotinib on other populations; ii)

since certain of the publications did not report on subgroups, the

present study mainly comprised subgroup analysis according to

control measures and sufficient subgroup analysis was not carried

out on other factors; and iii) numerous studies featured

small-sample analysis and there was lack of larger-sample

studies.

According to the results of the present study, it is

considered that for patients with NSCLC who have relapsed after

receiving two types of systemic chemotherapy, it is possible to

consider using anlotinib for treatment. At present, the drug is

administered in a 3-week cycle, at a recommended dose of 12 mg once

a day, with an interval for 1 week (i.e., the third week in the

cycle) after 2 weeks of treatment. However, it is necessary to

detect and prevent the occurrence of AEs. Blood pressure and blood

lipid levels should be monitored regularly and oral mucosa and skin

reactions should also be paid attention to. Anlotinib should also

be used with caution in patients who are at high risk of bleeding

and have hepatic renal insufficiency.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the study are

available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

BWZ designed the review and meta-analysis. YXZ and

RZY conceived and wrote the review. BWZ and YXZ acquired and

analyzed the data. BWZ and RZY analyzed and confirmed the integrity

of the data found in the literature. MDK was involved in designing

the research and drafting the manuscript. All authors contributed

to the analysis and reviewed the results and all authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

RCT

|

randomized controlled trial

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

RR

|

risk ratio

|

|

MD

|

mean difference

|

|

AE

|

adverse event

|

|

TKI

|

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

DCR

|

disease control rate

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

KPS

|

Karnofsky performance status

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer Statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality Worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D and Boshoff C:

The biology and management of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Nature.

553:446–454. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE

and Adjei AA: Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, risk

factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc. 83:584–594.

2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Aokage K, Yoshida J, Hishida T, Tsuboi M,

Saji H, Okada M, Suzuki K, Watanabe S and Asamura H: Limited

resection for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer as

function-preserving radical surgery: A review. Jpn J Clin Oncol.

47:7–11. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Duma N, Santana-Davila R and Molina JR:

Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, diagnosis, and

treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 94:1623–1640. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Broderick SR: Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant

immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Surg Clin.

30:215–220. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ruiz-Cordero R and Devine WP: Targeted

therapy and checkpoint immunotherapy in lung cancer. Surg Pathol

Clin. 13:17–33. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ,

Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, et al: Erlotinib versus

chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced

EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL,

CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study.

Lancet Oncol. 12:735–742. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S,

Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, Seto T, Satouchi M, Tada H, Hirashima T, et

al: Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal

growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase

3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 11:121–128. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liang W, Zhong R and He J: Osimertinib in

EGFR-mutated lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 384:6752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Belani CP and Eckardt J: Development of

docetaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 46

(Suppl 2):S3–S11. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cortot AB, Audigier-Valette C, Molinier O,

Le Moulec S, Barlesi F, Zalcman G, Dumont P, Pouessel D, Poulet C,

Fontaine-Delaruelle C, et al: Weekly paclitaxel plus bevacizumab

versus docetaxel as second- or third-line treatment in advanced

non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of the IFCT-1103

ULTIMATE study. Eur J Cancer. 131:27–36. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shen G, Zheng F, Ren D, Du F, Dong Q, Wang

Z, Zhao F, Ahmad R and Zhao J: Anlotinib: A novel multi-targeting

tyrosine kinase inhibitor in clinical development. J Hematol Oncol.

11:1202018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Han B, Li K, Wang Q, Zhang L, Shi J, Wang

Z, Cheng Y, He J, Shi Y, Zhao Y, et al: Effect of anlotinib as a

third-line or further treatment on overall survival of patients

with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The ALTER 0303 phase 3

Randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 4:1569–1575. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372:n712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni

P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA, et

al: The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in

randomised trials. BMJ. 343:d59282011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett

S and Sydes MR: Practical methods for incorporating summary

time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 8:162007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP and

Rothstein HR: A basic introduction to fixed-effect and

random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods.

1:97–111. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen B, Sun J, Cai W and Chen J: Efficacy

of anlotinib as a third-line therapy for non-small cell lung

cancer. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehabil. 28:558–560. 2021.

|

|

20

|

Dai X, Wang Y, Han L, Liu Y and Li R:

Clinical emcacy of AIllotinib in the treatment of advanced

non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Med Herald. 16:95–98. 2019.

|

|

21

|

Feng Y, Yao F, Wang W, Guo J and Zhu Z:

Short-term curative effect of anlotinib on non-small cell lung

cancer and its influences on CTC and VGEF levels in peripheral

blood and quality of life. J Clin Exp Med. 19:2399–2403. 2020.

|

|

22

|

Gou F, Yu D, Qiao Q and Zhou X: Clinical

observation of anlotinib in the treatment of advanced lung

adenocarcinoma with targeted therapy. Anti-Tumor Pharm. 10:343–348.

2020.

|

|

23

|

Han B, Kan N and Wang S: Explore the

clinical efficacy and short-term prognosis of Anlotinib in the

third-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC). Health Guide. 89–90. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

24

|

Han B, Li K, Zhao Y, Li B, Cheng Y, Zhou

J, Lu Y, Shi Y, Wang Z, Jiang L, et al: Anlotinib as a third-line

therapy in patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung

cancer: A multicentre, randomised phase II trial (ALTER0302). Br J

Cancer. 118:654–661. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Huang P, Li W and Zhang H: Effect of

anlotinib capsule on the level of VEGF and survival period in

advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Pract Cancer. 35:360–362.

2020.

|

|

26

|

Kong Q: Clinical effect of antinib in the

thirdline treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer and its clinical

significance security analysis. Chin J Mod Drug Appl. 14:164–166.

2020.

|

|

27

|

Liu Q, Li J, Wang K and Zhang Y: Clinical

efficacy of antinib in the treatment of patients with advanced lung

cancer after operation. Mod Diagn Treat. 31:2602–2604. 2020.

|

|

28

|

Luo K and Yu H: Clinical observation on

the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer with Anrotinib

III. Healthmust-Readmagazine. 7:452021.(In Chinese).

|

|

29

|

Si XY, Wang HP, Zhang XT, Wang MZ and

Zhang L: Efficacy and safety of anlotinib in 16 patients with

advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi.

57:830–834. 2018.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun X: Clinical efficacy and safety

analysis of third-line treatment with enrotinib for advanced

non-small cell lung cancer. Oriental Med Diet. 28:1172021.

|

|

31

|

Tian T, He M, Wu F, Lu Y and Liu Y:

Short-term efficacy of anlotinib in the treatment of non-small cell

lung cancer and its influence on serum tumor markers CTC VGEF and

side effects. J Hebei Nat Sci. 27:1908–1912. 2021.

|

|

32

|

Wang C: The efficacy of Anlotinib capsule

in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin Heal

Standard Management. 11:75762020.(In Chinese).

|

|

33

|

Yang Y: The Efficacy of Anlotinib as a

thirdor furtherline treatment in Patients with Advanced NSCLC.

Master's Thesis. Zhengzhou University; 2018, (In Chinese).

|

|

34

|

Yu C and Liu L: Observation on the effect

of third-line Anrotinib on advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

Medical Innovation of China. 18:69–72. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

35

|

Zhu Y: Short-term efficacy and life of

anlotinib thirdline and above in the treatment of advanced nonsmall

cell lung cancer. Healthmust-Readmagazine. 24:982021.(In

Chinese).

|

|

36

|

Nagano T, Tachihara M and Nishimura Y:

Molecular mechanisms and targeted therapies including immunotherapy

for non-small cell lung cancer. Current Cancer Drug Targets.

19:595–630. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhao T, Wang X, Xu T, Xu X and Liu Z:

Bevacizumab significantly increases the risks of hypertension and

proteinuria in cancer patients: A systematic review and

comprehensive meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 8:51492–51506. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Syed YY: Anlotinib: First global approval.

Drugs. 78:1057–1062. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xie C, Wan X, Quan H, Zheng M, Fu L, Li Y

and Lou L: Preclinical characterization of anlotinib, a highly

potent and selective vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2

inhibitor. Cancer Sci. 109:1207–1219. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

He C, Wu T and Hao Y: Anlotinib induces

hepatocellular carcinoma apoptosis and inhibits proliferation via

Erk and Akt pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 503:3093–3099.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yu G, Shen Y, Xu X and Zhong F: Anlotinib

for refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 15:e02429822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Abdel-Qadir H, Ethier JL, Lee DS,

Thavendiranathan P and Amir E: Cardiovascular toxicity of

angiogenesis inhibitors in treatment of malignancy: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 53:120–127. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ogawa C, Morita M, Omura A, Noda T, Kubo

A, Matsunaka T, Tamaki H, Shibatoge M, Tsutsui A, Senoh T, et al:

Hand-foot syndrome and post-progression treatment are the good

predictors of better survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

treated with sorafenib: A multicenter study. Oncology. 93 (Suppl

1):S113–S119. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|