Introduction

Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a relatively common

high-grade sarcoma, accounting for 5–10% of all soft tissue

sarcomas, most commonly occurring in the juxta-articular location

(1). SS located in the pleura are

rare and rarely reported in the literature, with the majority of

cases reported (2). Nearly 40 cases

of primary SS of the pleura (PSSP) have been reported since

Gaertner et al (3) published

the first case in 1996. It has been reported in all age groups.

Since most of the published papers are case reports, there is no

clear prognosis or recurrence rate reported in the literature. It

is frequently misdiagnosed as lung cancer or other pleural tumors

before surgery due to the lack of clinical and imaging specificity.

SS has a comparatively poorer prognosis and higher recurrence rate.

To date, <50 cases have been published in the English language.

The present study reported a rare case of two simultaneous PSSP in

an adolescent.

Case report

An 18-year-old male patient presented with a 1-month

history of repeated sporadic dry cough and wheezing admitted to the

The Second People's Hospital of Liaocheng (Linqing, China). The

patient had no history of smoking or asbestos exposure. The cough

worsened after exercise and in the lateral decubitus position

accompanied by general fatigue, no fever, no blood in sputum and no

hemoptysis. The patient's laboratory results were as follows:

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 52 mm/h ↑ (normal range, ≤20 mm/h);

platelets, 383×109/l ↑ (normal range,

100–300×109/l); C-reactive protein, 98.46 mg/l ↑ (normal

range, 0–10 mg/l); prothrombin time, 15.40 sec ↑ (normal range,

9.4–12.5 sec); fibrinogen, 5.8 g/l ↑ (normal range, 2–4 g/l),

D-dimer determination, 5.57 mg/l ↑ (normal range, 0–0.5 mg/l).

Hydropleural biochemistry was as follows: Hydropleural protein,

51.8 g/l ↑ (normal range, 0–30 g/l); hydropleural lactate

dehydrogenase, 1,022 U/l ↑ (normal range, 0–200 U/l); hydropleural

cholesterol, 1.62 mmol/l ↑ (normal range, 0–1.60 mmol/l). Computed

tomography of the chest revealed two tumors in the left parietal

pleura (7.8×2.8 cm; 6.5×5.8 cm), with unclear boundaries with the

adjacent chest wall, localized thickening of soft tissue in the

left anterior intercostal space at 8 and 9, left pleural effusion

(considered hemorrhagic), incomplete expansion of the left upper

lobe of the lung and shadow consolidation of the left lower lobe of

the lung (Fig. 1). Abdominal and

pelvic CT and bone scans were normal without evidence of

metastasis. Three pleural effusion cytological examinations (one

per day for three consecutive days) showed no tumor cells. The

patient refused to undergo preoperative MRI, positron emission

tomography-CT and biopsy for financial reasons. The patient

underwent a left intrathoracic tumor resection. During the

operation, a fifth intercostal incision was performed on the left

lateral chest. The exploration revealed pleural adhesion,

separation adhesion, blood clots in the chest, the formation of

pleural fiberboard in the left lower lobe of the lung, and two

lesions in the chest; the larger one was located near the spine at

the level of the lower lung ligament, closely related to the

descending aorta, and the other one was located in the costophrenic

Angle. The hemoaccumulation in the chest was cleared, two lesions

were completely resected. During the operation, rapid freeze

pathology examination, performed according to standard procedures,

was used to confirm that the surgical margin was negative, and the

final specimen pathology, performed according to standard

procedures, also confirmed that the margin was negative. The

operation was deemed successful.

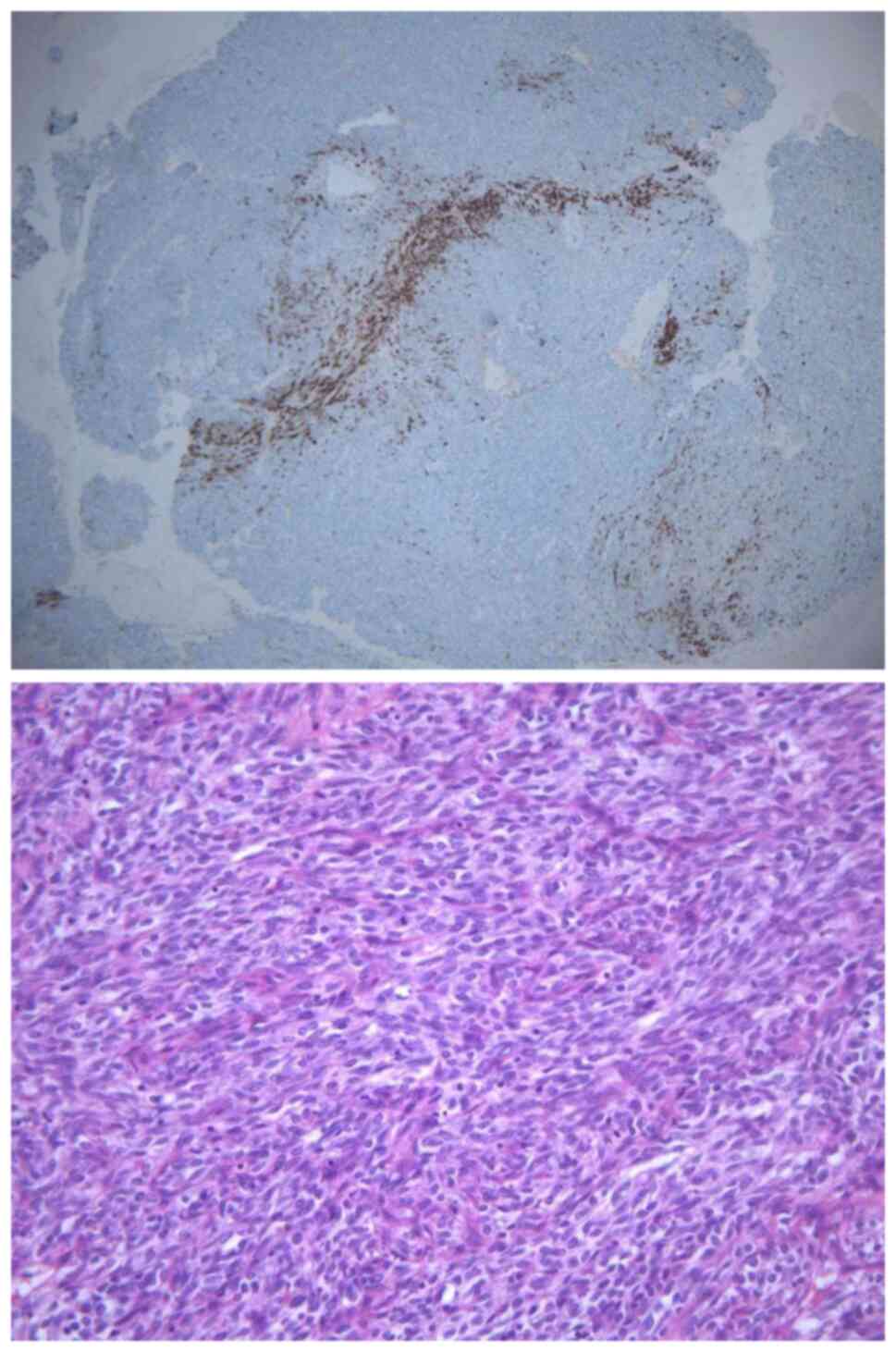

By histopathology with H&E staining (performed

according to standard procedures; Fig.

2, bottom), the tumor was confirmed to be a monophasic synovial

sarcoma (consisting of spindle-like cells in a perivascularomatous

vascular morphology, with mitotic or interwoven bundles of

spindle-like cells). Immunohistochemistry performed according to

routine procedures was used revealed the following: Cytokeratin

(CK) (−), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (−), CD99 molecule

(CD99/MIC-2) (−), signal transducer and activator of transcription

6 (STAT6) (−), smooth muscle actin (SMA) (−), Desmin (−), receptor

tyrosine kinase (CD117) (−), WT1 transcription factor (WT1) (−),

RING finger-like protein Ini1 (INI-1) (−), premelanosome protein

(HMB45) (−), tumor protein p63 (p63) (small amount +), BCL2

apoptosis regulator (Bcl-2) (part +), antigen identified by

monoclonal antibody Ki 67 (Ki67) (+ 40%), methylation of histone 3

lysine 27 (H3K27ME3) (+), cyclin D1 (+),CD34 molecule (CD34) (+),

calretinin (CR) (+) (Fig. 2, top),

podoplanin (D2-40) (part +), transducer-like enhancer split 1

(TLE-1) (+) and SS18 subunit of BAF chromatin remodeling complex

SSX family member 2 (SS18-SSX) (+). In brief, consecutive parallel

sections were stained with the following antibodies (the dilution

was according to the manufacturers' recommendations for

immunohistochemistry for each antibody): CK [rabbit anti-human

monoclonal antibody (mAb); cat. no. RAB-0050], EMA (rabbit

anti-human mAb; cat. no. kit-0011), CD99 (mouse anti-human mAb;

cat. no. MAB-0059), STAT6 (rabbit anti-human mAb; cat. no.

RMA-0845), SMA (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. kit-0006), Desmin

(mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. MAB-0766), CD117 (rabbit anti-human

mAb; cat. no. kit-0029), WT1 (rabbit anti-human mAb; cat. no.

MAB-0678), INI-1 (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. MAB-0696), HMB45

(rabbit anti-human mAb; cat. no. MAB-0098), p63 (mouse anti-human

mAb; cat. no. MAB-0694), Bcl-2 (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no.

MAB-0711), Ki67 (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. MAB-0672), cyclin

D1 (rabbit anti-human mAb; cat. no. RMA-0541), CD34 (mouse

anti-human mAb; cat. no. kit-0004), CR (mouse anti-human mAb; cat.

no. MAB-0716), D2-40 (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. MAB-0567),

TLE-1 (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. MAB-0686), SS18-SSX (rabbit

anti-human mAb; cat. no. RMA-1049; all from Maixin Fuzhou) and

H3K27ME3 (mouse anti-human mAb; cat. no. P68431; Absin). The

secondary antibodies used were goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC antibody

(cat. no. abs20140; Absin) and Elivision™ plus polymer HRP

(mouse/rabbit) IHC Kit (cat. no. KIT-9903; Maixin Fuzhou). Genetic

testing (fluorescence in situ hybridization), performed

according to routine procedures (4), indicated SS-18 (+) (Fig. 3).

After surgery, the patient received ifosfamide and

doxorubicin combined chemotherapy. He underwent four cycles of

chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide 9 g, once a day for 5 days;

doxorubicin 150 mg, once a day for 3 days; 21 days as a cycle) and

has been well followed up. After six months of follow-up, the

symptoms of dry cough and wheezing disappeared. All of the

laboratory results were within normal limits and no post-operative

complications, tumor recurrence or metastasis occurred.

Discussion

PSSP is a highly malignant and rare tumor type that

is common in adolescents and is not associated with smoking.

Typical symptoms include acute chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis and

hemorrhagic effusion in the ipsopleural cavity (5). Diagnosis of SSP is often difficult

owing to its rarity and its similarity (clinically and

histologically) to other types of pleural tumor, particularly

sarcomatous mesothelioma. The most common presentation is a

well-defined mass with effusion on CT (2). On CT of the chest, a synovial sarcoma

of the pleura is commonly characterized as a heterogeneously

enhanced mass with well-defined margins, cortical bone destruction,

tumor calcifications and tumor infiltration of the chest wall

musculature (6). Duran-Mendicuti

et al (7) reported 5 cases

of primary pleural synovial sarcoma, showing radiologically uneven

enhancement and well-defined masses without calcification. The

pathologic types may be divided into monophasic, biphasic and

poorly differentiated types. In monophasic synovial sarcoma,

spindle cells may be seen interwoven into bundles.

Immunohistochemical examination of synovial sarcoma is

characterized by positive staining of cytokeratin and epithelial

cell membrane antigen, negative staining of nerve (S100) and smooth

muscle markers and uniform staining of epithelial cell marker

BerEp4, which facilitates the differentiation from malignant

mesothelioma. Most synovial sarcomas exhibit at least an exocentric

immune response to cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigens,

which are usually more prominent in epithelial components. CD99 and

Bcl-2 were also detected in most cases.

Therefore, the diagnosis of PSSP requires clinical,

radiological, pathological and immunohistochemical examination to

exclude other primary tumors and metastatic sarcomas.

Although there is no standardized treatment for

PSSP, based on the generally effective treatment for soft tissue

sarcomas, a multidisciplinary treatment regimen that includes

radical excision as the primary means of treatment, combined with

chemotherapy (doxorubicin and ifosfamide) and radiotherapy, may be

recommended (8). Prior to radical

resection, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be beneficial because it

causes tumor volume reduction and has the potential to treat

micrometastases, but there is no experience in PSSP. A previous

study reported that the disease-free survival of 5 patients after

surgical resection of PSSP was 2–14 months (7). Despite aggressive combination therapy,

the prognosis is uncertain and long-term follow-up is

warranted.

The present study described a case of primary

pleural synovial sarcoma, the first published case to date of two

simultaneous intrapleural tumors, treated by radical resection plus

chemotherapy. Postoperative pathology, immunohistochemistry,

genetic testing and radiological examination confirmed malignant

tumors. At six months after surgery, the patient is currently in

good health with no recurrence or metastasis.

In conclusion, PSSP is a rare and aggressive

neoplasm in adolescents; it is difficult to diagnose with imaging

alone, especially in the case of two masses in the pleura at the

same time and hemorrhagic pleural effusion. Genetic testing may

help confirm the diagnosis. Radical surgery is the main treatment

in combination, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. The long-term

outcome remains to be seen, as PSSP has a poor prognosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YZ and CM designed the study. YZ was the principal

person responsible for the study and wrote the original manuscript.

XX provided the surgical details described in the manuscript. YZ,

CM and HL performed histological analysis of the specimens and

provided all pathological details described in the study. YZ and CM

performed analysis and interpretation of CT imaging data. CM, XX

and HL performed a critical literature review, contributed to the

acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and contributed to

the drafting of the Introduction and Discussion sections. YZ and XX

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the study.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the

ethical standards from the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its

later amendments; local ethical approval was obtained from the

Ethics Committee of the Second People's Hospital of Liaocheng

(Linqing, China).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the case information and images to be published in this

case report.

Competing interests

All authors declare they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Attanoos RL and Pugh MR: The diagnosis of

pleural tumors other than mesothelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

142:902–913. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sandeepa HS, Kate AH, Chaudhari P, Chavan

V, Patole K, Lokeshwar N and Chhajed PN: Primary pleural synovial

sarcoma: A rare cause of hemorrhagic pleural effusion in a young

adult. J Cancer Res Ther. 9:517–519. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gaertner E, Zeren EH, Fleming MV, Colby TV

and Travis WD: Biphasic synovial sarcomas arising in the pleural

cavity. A clinicopathologic study of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

20:36–45. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Amary MF, Berisha F, Bernardi Fdel C,

Herbert A, James M, Reis-Filho JS, Fisher C, Nicholson AG,

Tirabosco R, Diss TC and Flanagan AM: Detection of SS18-SSX fusion

transcripts in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded neoplasms: Analysis

of conventional RT-PCR, qRT-PCR and dual color FISH as diagnostic

tools for synovial sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 20:482–496. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu Y, Lin J, Sun H and Xie S: Primary

pleural synovial sarcoma in an adolescent: A case report. Transl

Cancer Res. 9:3771–3775. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kang MK, Cho KH, Lee YH, Han IY, Yoon YC,

Park KT, Kang DK and Kim BM: Primary synovial sarcoma of the

parietal pleura: A case report. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.

46:159–161. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Duran-Mendicuti A, Costello P and Vargas

SO: Primary synovial sarcoma of the chest: Radiographic and

clinicopathologic correlation. J Thorac Imaging. 18:87–93. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yamaki M, Yonehara S and Noriyuki T: Large

primary pleural synovial sarcoma with severe dyspnea: A case

report. Surg Case Rep. 3:292017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|