Introduction

The term pituitary apoplexy (PA) was initially

introduced by Brougham in 1950 (1),

defined as an emergency condition caused by hemorrhage or

infarction of the pituitary gland. However, PA can be generally

neglected in 25% of pituitary tumors and there may only be

radiological or histopathological evidence of infarction and/or

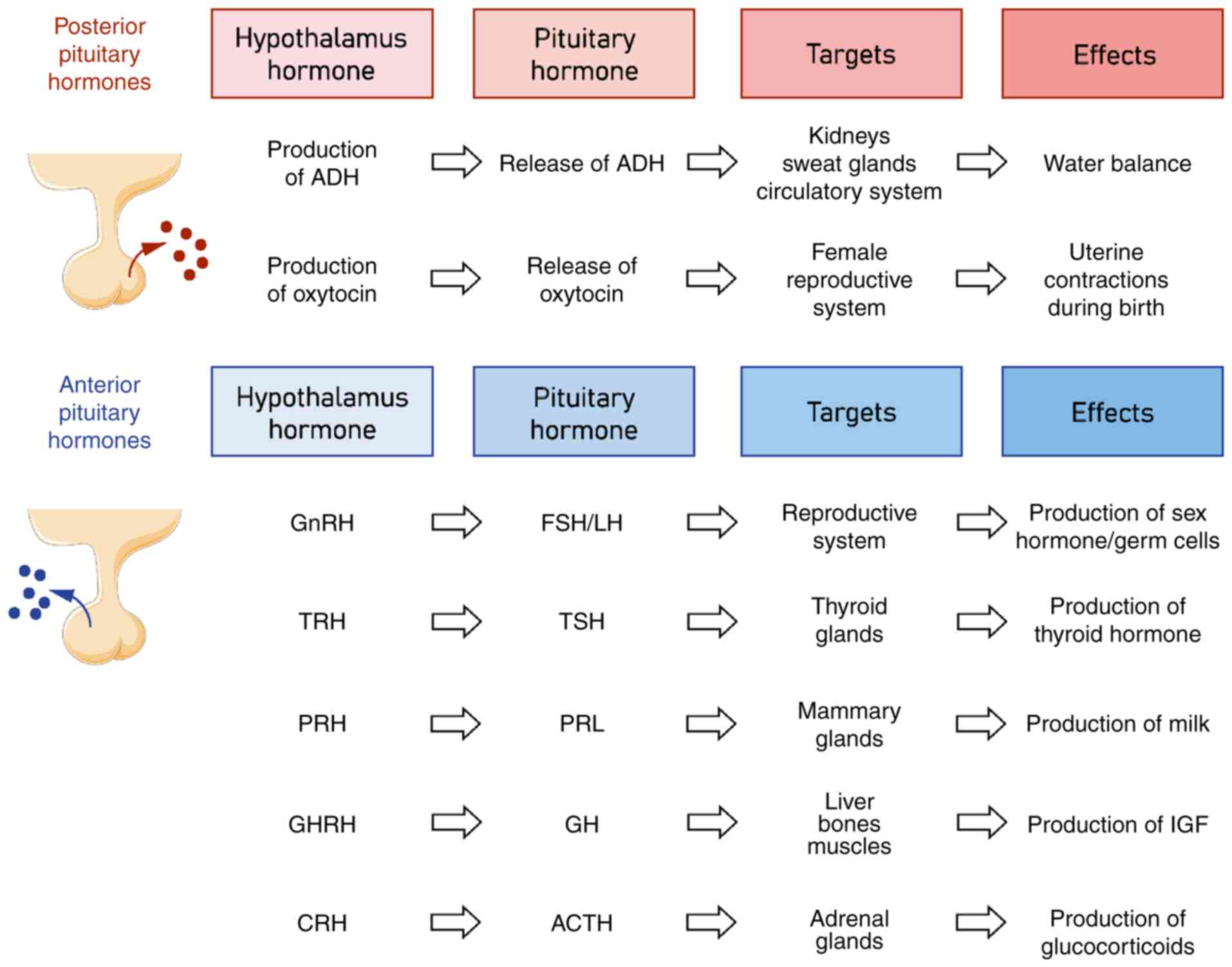

hemorrhage without any clinical manifestation (2). In the present article, PA refers to

clinically diagnosed PA with classical symptoms.

The prevalence of PA reported in different studies

ranges from 0.6 to 7% (3–7), suggesting that numerous cases were

undiagnosed and did not receive any clinical attention (8). While the pathophysiology of PA remains

elusive, several risk factors have been identified, such as

fluctuation of blood pressure (BP), use of anticoagulant drugs,

major surgeries, pregnancy and pituitary function test (9–11).

Clinical symptoms vary from person to person, commonly manifesting

as sudden onset of headache, visual field defect, diplopia,

ophthalmoplegia, decreased consciousness, increased urine volume,

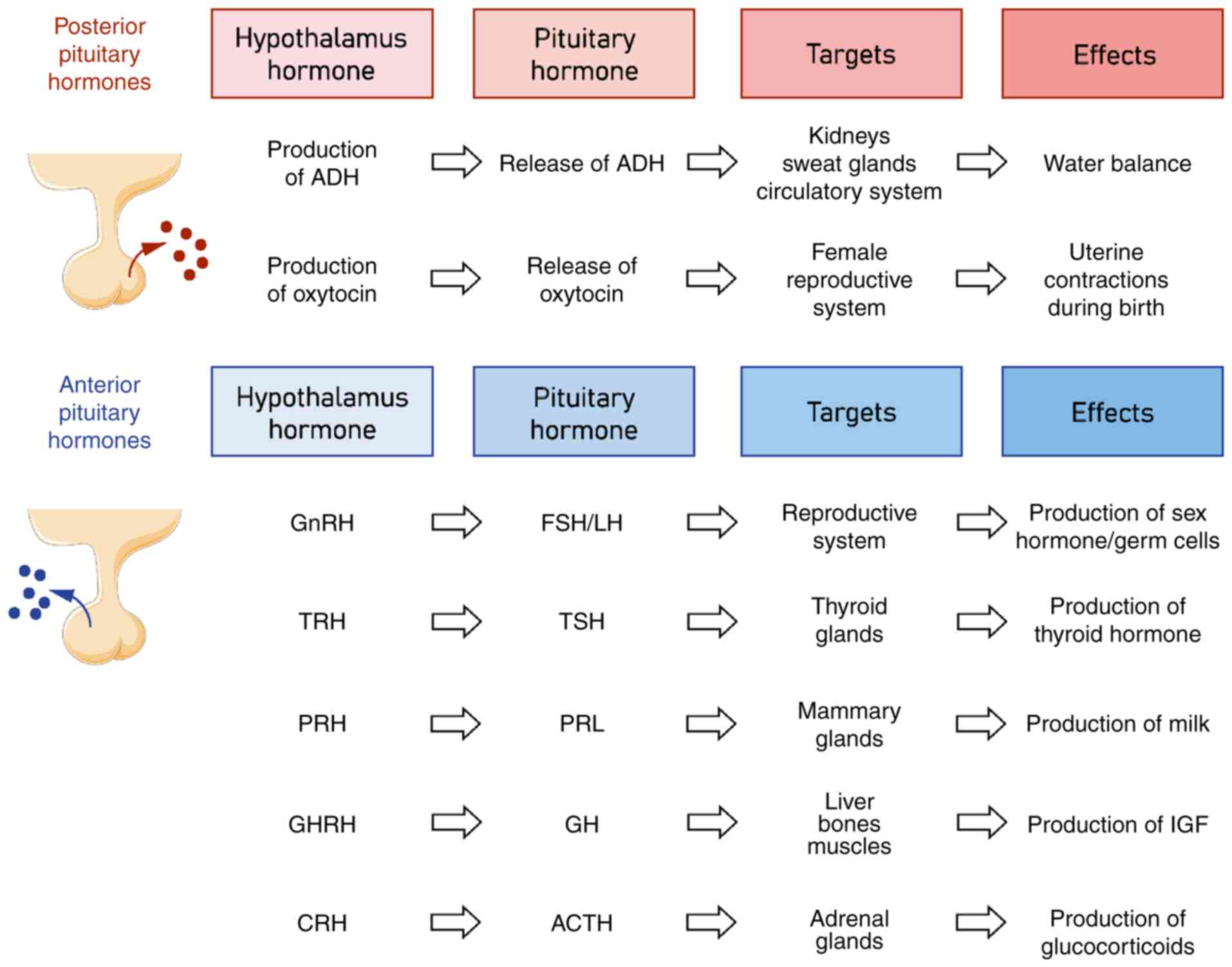

nausea and vomiting (12–14). Dysfunctions in the

hypothalamic-pituitary hormone axis can result in a lack of various

pituitary-related hormones, which may lead to physiological

disorders in several ways (Fig. 1).

Hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency secondary to PA may weaken

the body's tolerance to surgical trauma. Glucocorticoid and thyroid

hormones both have a role in post-operative stress. Glucocorticoids

help maintain BP and blood sugar, facilitate fat mobilization,

combat cellular damage and suppress inflammatory responses

(15), and thyroid hormones can

speed up the metabolism and increase peripheral cells' utilization

of glucose (16). The choice of

treatment between hormonal replacement therapy and trans-sphenoidal

resection is determined based on the severity of neuro-ophthalmic

symptoms and the patient's capacity to undergo a second surgery

(2).

| Figure 1.Hypothalamic-pituitary hormone axis

and its main functions. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH,

antidiuretic hormone; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; FSH,

follicle-stimulating hormone; GH, growth hormone; GHRH, growth

hormone releasing hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone;

LH, luteinizing hormone; PRH, prolactin releasing hormone; PRL,

prolactin; TRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone; TSH, thyroid

stimulating hormone. |

However, presenting as the initial sign of unknown

pituitary tumors, it can be a challenging task to diagnose PA

post-surgery due to its symptomatic overlap with postoperative

complications. It is a rare postoperative complication that may

have severe consequences if not treated timely and properly. Due to

the lack of reviews on PA after surgery, the current article

presented a clinical case and summed up the characteristics of

relevant cases published over the years.

Case report

A 64-year-old female with a history of subtotal

hysterectomy 20 years prior presented with vaginal bleeding

persisting for three months and was admitted in Shengjing Hospital

of China Medical University (Shenyang, China) in March 2023. The

patient's body mass index was 24.2 kg/m2 (body height,

164 cm; body weight, 65 kg). The obstetric history included two

pregnancies-one ending in abortion and the other in a vaginal

birth. At the age of 44 years, the patient underwent a subtotal

hysterectomy and left adnexectomy due to multiple uterine

leiomyomas and a lateral ovarian cyst, with postoperative pathology

confirming benignity. Irregular human papillomavirus (HPV) and

thinprep cytology test (TCT) screening were conducted post-surgery,

and the last screening was 2 years prior and the results remained

negative. After undergoing minor but persistent vaginal bleeding

for 3 months, the patient tested HPV-16 positive and negative for

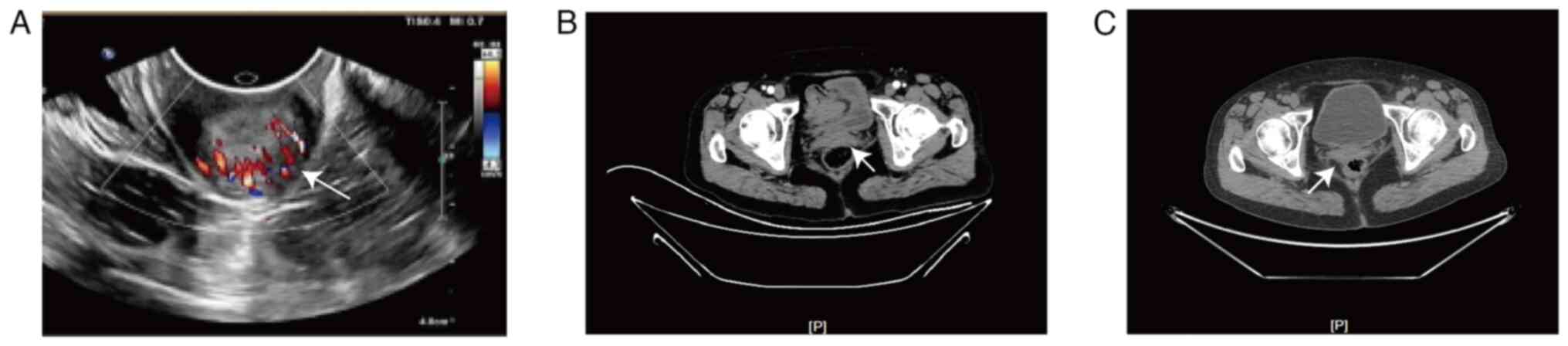

intraepithelial lesion or malignancy on TCT. The pelvic ultrasound,

computerized tomography (CT) and positron emission

tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) identified a moderately

hyperechoic mass in the cervical stump region, which was highly

suggestive of cancer (Fig. 2).

Gynecological examination revealed normal vulvar development with

signs of aging and a smooth vaginal canal. An exogenous lesion with

a diameter of ~2.5 cm was observed at the stump of the cervix,

exhibiting lesion contact bleeding. The anterior fornix was shallow

and the pelvic cavity was with no obvious abnormalities in the

adnexal areas. The patient reported no comorbidities, aside from a

sulfonamide allergy. General examination was unremarkable, except

for admission BP of 148/96 mmHg. According to the latest guideline

of hypertension in China (17),

hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140 mmHg/or diastolic BP

≥90 mmHg. The patient's BP was monitored and a cardiologist was

consulted. During hospitalization, the patient's BP was stable,

ranging from 120/80 to 140/90 mmHg. The patient cooperated well in

the physical examination. The bilateral pupils were equally large

and round with a diameter of 3 mm and had no limitation of eye

movement or visual field defect. The patient exhibited full

mobility in all four limbs with normal muscle force and strength

and neither had a history of pituitary adenoma nor manifested any

related symptoms. The patient underwent tissue biopsy and cervical

stump adenocarcinoma was diagnosed. After comprehensive

pre-operative evaluations, including PET-CT, the patient underwent

open extensive stump cervicectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection and

transcystoscopic bilateral ureteral stenting. Pelvic drainage and

vaginal drainage were used. The surgery proceeded smoothly with an

intraoperative bleeding volume of 100 ml. Intraoperative anesthesia

and medication details are provided in Fig. S1 [Illustrator 27.7 (Adobe, Inc.)

was used to generate the translated version of this image]. The

patient's BP remained stable during the operation and no

hypotension was detected prior to or after the surgery. After the

gynecological operation, the patient was treated with intravenous

cefazolin sodium (Sinopharm CNBG Zhongnuo Pharmaceuticals Co.,

Ltd.) 0.5 g per 8 h, intramuscular enoxaparin sodium [Sanofi

Aventis (Beijing) Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.] 40 mg per day,

intravenous methylprednisolone (Pharmacia & Upjohn Co., Ltd.)

20 mg per day and other supportive care (methylprednisolone is

administered as a common treatment at the Enhanced Recovery After

Surgery ward to alleviate peri-operative stress and inflammation).

From postoperative day 1 (POD1), the patient complained of the

sudden onset of a headache [pain visual analogue scale (VAS) score

(18), 4/10] and drowsiness. Since

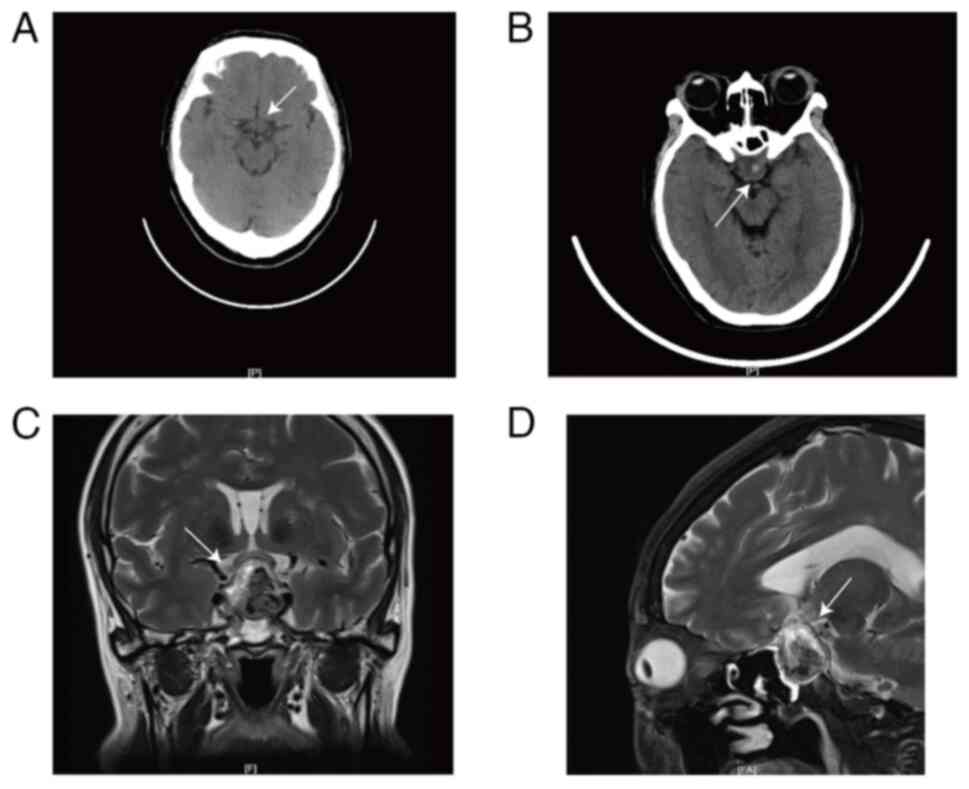

the pre-operative PET-CT did not indicate any pituitary tumor

(Fig. 3A), it was inferred that the

patient's symptoms may be due to general anesthesia and the

postoperative analgesia pump and the pump was turned off

immediately. On POD2, the patient still reported headaches and a

neurosurgery consultation was started. The neurosurgery doctor

suggested recording a head CT but the patient perceived her

headache to be of mild severity and signed to refuse relevant

tests. On POD3, the patient's BP fluctuated between 120/70 and

145/85 mmHg. It was not until the patient's headache worsened (pain

VAS 7/10) and a new complaint of blurred vision and blepharoptosis

of the left eye occurred on POD4 that she consented to further

examination. The patient's Glasgow coma scale score was 3-5-6

points (19). A head CT scan and an

ophthalmic consultation were carried out immediately, revealing

multiple lacunar infarctions and local density increases in the

sella turcica and suprasellar regions (Fig. 3B). Enhanced pituitary MRI showed a

2.4×1.7×2.6 cm occupation in the sellar area with a heterogeneous

signal, indicating a pituitary macroadenoma with apoplexy (Fig. 3C and D). Ophthalmic assessments

showed bitemporal hemianopsia and abnormal findings in the fundus

photography and visual pathway images (data not shown). Laboratory

tests indicated panhypopituitarism (Table I). The patient was promptly

transferred to the neurosurgery ward. Considering the visual field

defect was stable, there was no indication of an emergency surgery

and hydrocortisone (Tianjin Jinyao Amino Acid Co., Ltd.; 100

mg/day) replacement therapy was used to complete enhanced head CT

and arterial angiography, and transsphenoidal hypophysical lesion

resection through the neuroendoscope under general anesthesia was

carried out successfully on POD12. After the neurosurgery

operation, the patient took desmopressin acetate tablets [Huilin

(Sweden) Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd.] 0.1 mg to treat postoperative

diabetes insipidus, sustained-release potassium tablets (Shenzhen

Zhonglian Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) 1 g three times per day to

treat hypokalemia and prednisolone acetate tablets (Tianjin Tianyao

Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd.) 10 mg at 8:00 a.m. and 5 mg at 4:00 p.m.

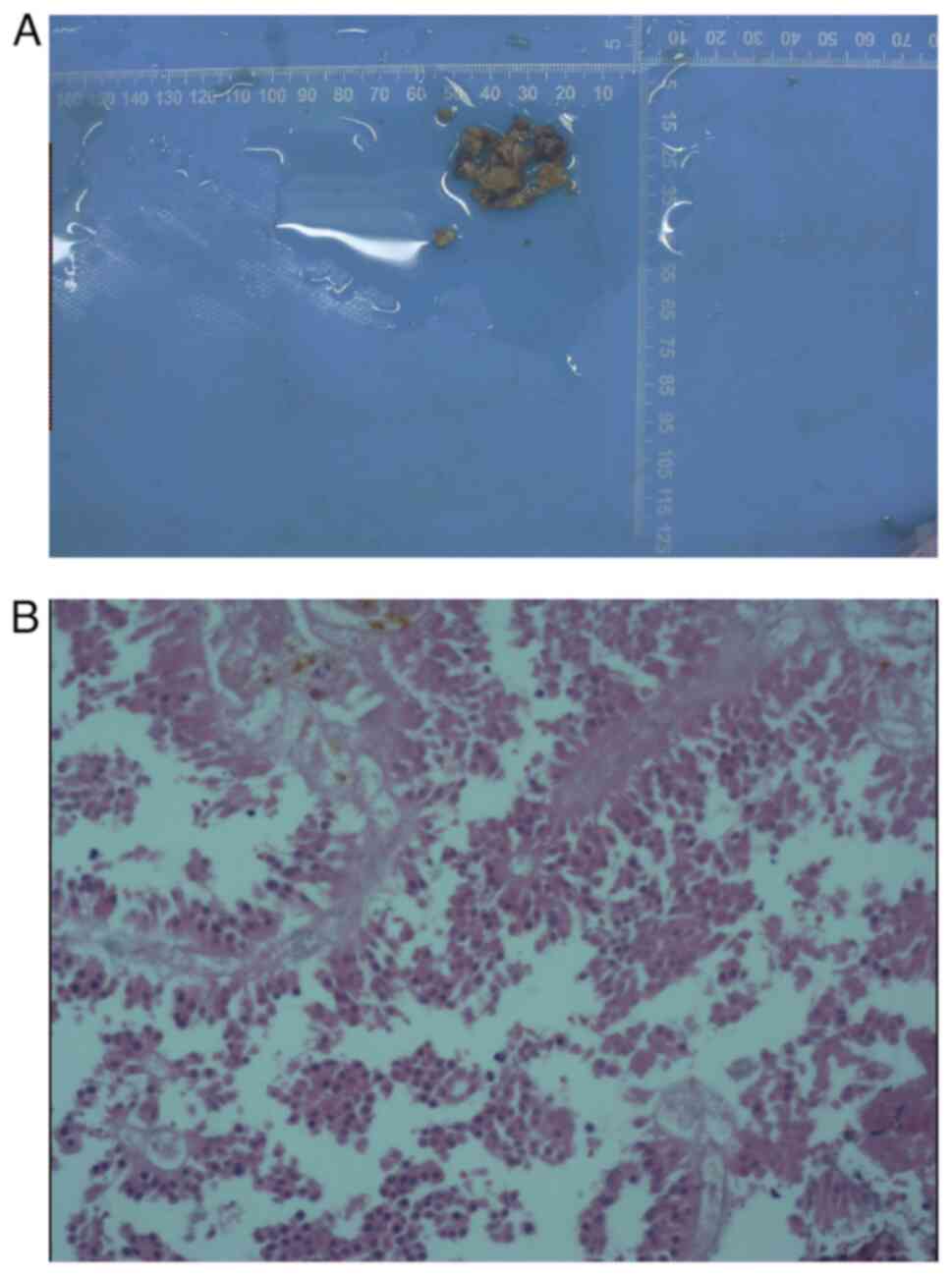

each day. Postoperative pathology was performed by reticulin fiber

staining with kit no. G3535 from Solarbio Science and Technology

(Beijing) Co., Ltd (20), and it

indicated hemorrhage of pituitary tumor (Fig. 4). The patient reported complete

resolution of headaches, bitemporal hemianopia and visual field

improvement the day after the operation and was discharged from the

hospital a week later. The patient reported mild blurry vision

during the follow-up of six weeks after the neurosurgery operation.

After discharge, the patient underwent follow-up every three

months, and her hormone levels completely returned to normal. The

patient was advised to undergo hormone level assessments and

pituitary imaging every six months, with continued lifelong

follow-up.

| Table I.Hormone and ion levels of the patient

at different stages. |

Table I.

Hormone and ion levels of the patient

at different stages.

| Time-point | K+,

mmol/l | Na+,

mmol/l | FT3, pmol/l | FT4, pmol/l | TSH, µmol/l | ACTH-8:00 a.m.,

pg/ml | Cortisol-8:00 a.m.,

µg/dl | FSH, µIU/ml | LH, µIU/ml | Prolactin,

ng/ml |

|---|

| Pre-operation | 3.78 | 139 | 4 | 9.42 | 1.75 | 16.74 | 15.6 | 23.45 | 6.09 | 38.28 |

| Between two

operations | 3.27↓ | 135↓ | 2.48 | 6.81↓ | 0.19↓ | 3.83↓ | 5.63↓ | 3.77↓ | <0.2↓ | 1.13↓ |

| Post-operation | 3.24↓ | 137 | <1.54↓ | 8.48↓ | 0.2↓ | 2.25↓ | 11.94 | 2.49↓ | <0.2↓ | 1.57↓ |

| 6 weeks after the

operation | 4.49 | 141 | 3.24 | 12.22 | 0.9 | 11.9 | 10.11 | 2.41↓ | 0.62↓ | 3.75 |

| Normal ranges | 3.5–5.5 | 136-145 | 2.43–6.01 | 9.01–19.05 | 0.3–4.8 | 7.2–66.3 | 6.02–18.4 | 6.74–113.59 | 10.87–58.64 | 2.74–19.64 |

Discussion

PA is a rare postoperative complication that may be

life-threatening if not diagnosed and treated properly. It is

usually caused by a sudden ischemic or hemorrhagic infarction of a

preexisting pituitary adenoma, while only pituitary apoplexy rarely

occurs in normal pituitary glands. Bonicki et al (3) reported that PA occurs in 5% of

patients with pituitary adenomas; however, >40% of PA cases have

never been diagnosed with a pituitary tumor prior to onset

(21). PA is related to a variety

of inducible factors, but its exact pathogenesis remains elusive.

Due to the specific features of the pituitary vascular system,

pituitary tissue is more susceptible to hypoperfusion, ischemia and

intraoperative embolism, particularly during pump-on surgery.

During the literature review for the current study, it was found

that predisposing factors of PA included not only transient

hypertension or hypotension, but also diabetes, angiographic test,

cardiac surgery, hemodialysis, pituitary dynamic function test,

radiation therapy, positive pressure mechanical ventilation and

anticoagulant therapy (22).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first case report of PA after gynecological malignancy. Since

the pre-operative PET-CT did not indicate any pituitary tumor,

postoperative symptoms such as headache, visual field defect,

ptosis and hypopituitarism were confused with common postoperative

complications and PA was not detected in the initial stage. This

may be for the following two primary reasons. First, PET-CT lacks

specificity and sensitivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary region,

potentially resulting in undetected pituitary microadenomas.

Furthermore, the pituitary adenoma became enlarged due to

hemorrhage post-surgery, thereby facilitating detection. However,

headaches likely occurred due to extravasation of blood into the

subarachnoid space, causing meningeal irritation (22). Bitemporal hemianopia is the most

common type of visual field defect caused by a pituitary tumor,

which occurs due to the PA pressing on the middle of the optic

chiasma (14). Ptosis presented as

a result of oculomotor nerve compression and hypopituitarism was a

sign of pituitary dysfunction. Besides, severe hypoglycemia and

hyponatremia may occur due to a reduced glucocorticoid effect

because of low cortisol response, as well as water overload caused

by adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency.

A total of four primary factors contributing to the

occurrence of PA were identified for the present case. First,

general anesthesia carries a greater risk of low BP than local

anesthesia. General anesthesia may also lead to reduced cerebral

perfusion. Second, surgery can cause intravascular fluid to spread

into the interstitial space, leading to edema and a drop in BP.

Third, blood loss may also be a contributing factor. Although only

100 ml of blood loss was stated in the surgical record, the patient

underwent a major resection and lymph node dissection with

postoperative nausea and vomiting, which indicated the possibility

of local bleeding after abdominal closure and blood loss may be

difficult to estimate accurately. Fourth, anticoagulant therapy is

another risk factor, as it increases the risk of bleeding from

damaged pituitary tissue.

PA can also occur in various types of surgery,

particularly in surgery of the circulatory system. A literature

search was conducted through PubMed, using ‘pituitary apoplexy’ and

‘surgery or operation’ as key terms to identify relevant articles

published between 1984 and 2023. The search was limited to articles

in English and only studies with sufficient information were

included in the literature review (Table II). Based on the literature review,

PA after surgery mostly occurred in males (76%), with an average

age of 53 years for women and 68 years for men. Only 8% of cases

had known pituitary disease (23,24).

Clinical symptoms usually occur on the operation day or on POD1

(72%) and headache (76%) was the main and the earliest complaint in

most cases. This symptom was possibly triggered by dural stretching

and meningeal irritation caused by extravasation of blood and

necrotic tissue into the subarachnoid space (25). Further examination of the literature

indicated that visual disturbances were mentioned in 64% (visual

deterioration in 24%, diplopia in 24%, visual defects in 20% and

loss of light reflex in 20%), which was caused by pressure on

different parts of the optic nerve and oculomotor nerve involvement

may present as ptosis (44%). In addition, adrenal insufficiency may

reduce the level and the efficiency of glucocorticoids and

eventually cause arterial hypotension and/or hypoglycemia, as well

as varying degrees of consciousness change, which was noted in 12%

of cases in the present review.

| Table II.Summary of information on PA cases

during and after surgery from the literature review and the present

case. |

Table II.

Summary of information on PA cases

during and after surgery from the literature review and the present

case.

| Authors, year | Age, years/sex | Prior lesion | Operation

method | Clinical

presentation | Onset time | Pituitary imaging

MRI/CT | Potential risk

factors | Treatment hormone

replacement therapy | Surgery | Prognosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Mura et

al, | 85/male | – | Laparoscopic | Left palpebral | During the | CT: Pituitary

gland | Preoperative | Dexamethasone | – | – | (34) |

| 2014 |

|

| colorectal | ptosis, | operation | increase; | anticoagulant | 4 mg ×2/day |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| resection | anisocoria, |

| MRI: Pituitary

gland | therapy, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| divergent |

| increase with | intraoperative |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| strabismus, |

| hematoma | BP fluctuation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| mydriasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| without photo- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| motor reflex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| McClain et

al, | 75/female | – | Elective | Headache, | POD1 | CT: A large

sellar | History of | – | Urgent | Ptosis and | (35) |

| 2022 |

|

| rotator | vomiting, |

| mass; | essential |

|

transsphenoidal | ophthal- |

|

|

|

|

| cuff repair | diplopia, |

| MRI: A sellar

and | hypertension |

| endoscopic | moplegia |

|

|

|

|

|

| inability to |

| suprasellar

mass |

|

| resection of

the | completely |

|

|

|

|

|

| open the |

| effect

compressing |

|

| pituitary mass | recovered |

|

|

|

|

|

| right eye |

| the optic

chiasm |

|

|

| and visual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| field deficits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| stabilized |

|

| Liberale et

al, | 73/male | – | Subrenal | Diplopia,

right | On the | MRI: A large

sellar | Preoperative | Cortisone |

Transsphenoidal | Partially | (36) |

| 2006 |

|

| aortic | palpebral | operation | mass

compressing | anticoagulant | acetate 50 mg/ | adenectomy | recovered the |

|

|

|

|

| abdominal | ptosis, | day | back carotid

arteries | therapy | morning and |

| right third |

|

|

|

|

| aneurysm | mydriasis, |

| and the

optical |

| 25 mg/evening, |

| oculomotor |

|

|

|

|

| repair by | divergent |

| chiasma |

| sodique |

| palsy and |

|

|

|

|

| subcostal | strabism |

|

|

| levothyroxin, |

| remained |

|

|

|

|

| bilateral |

|

|

|

| 50 g/day |

| stable during |

|

|

|

|

| laparotomy |

|

|

|

|

|

| the 4-year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| follow-up |

|

| Naito et

al, | 14/female | – | Recurrent | Headache | POD1 | CT: A tumor | Hemodynamic | l-T4 treatment | – | Improved | (37) |

| 2019 |

|

| cardiac | and visual |

| surrounding

the | instability | for 3 months |

| visual field |

|

|

|

|

| myxoma | impairment |

|

hypothalamopituitary | during

surgery, |

|

| of both eyes |

|

|

|

|

| resection |

|

| lesion; | use of |

|

| before |

|

|

|

|

| surgery |

|

| MRI: An intra-

and | anticoagulant |

|

| discharge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| supra-sellar

tumor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| compressing

optic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| chiasma and

bilateral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| optic nerves |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hidiroglu et

al, | 47/male | – | Coronary | Ptosis of both | POD2 | CT: A solid

mass | – | – |

Transsphenoidal | – | (38) |

| 2010 |

|

| artery bypass | eyes, headache |

| compressing the

optic |

|

| adenectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

| grafting |

|

| chiasm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| operation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yakupoglu et

al, | 74/male | – | Open three- | Right ophtha- | 6 h after | CT: A mass on

the | Hemodynamic | Intravenous | Transcranial | Full recovery | (39) |

|

2010 |

|

| vessel | lmoplegia with | the | pituitary

gland; | changes | hydrocortisone | adenoma | of ptosis, |

|

|

|

|

| CABG and | ptosis, right | operation | MRI: Pituitary |

| 50 mg/day,

oral | excision | visual field |

|

|

|

|

| insertion of | mydriasis, |

| macroadenoma

with |

| levothyroxine |

| deficits and |

|

|

|

|

| a saphenous | headache |

| haemorrhage

and |

| 0.2 mg/day |

| mental |

|

|

|

|

| vein graft |

|

| infarction |

|

|

| changes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| within |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 weeks of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| surgery |

|

| Yoshino et

al, | 78/male | – | Right upper | Headache, | POD6 | MRI: A high- | – | Hydrocortisone | – | Complete | (40) |

| 2014 |

|

| and middle | sudden |

| intensity area

inside |

| 200 mg/day |

| recovery |

|

|

|

|

| lobectomy | increase in |

| the pituitary

gland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and lymph | urine volume |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| node |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| dissection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Joo et al,

2018 | 73/male | – | Lumbar | Severe | POD2 | CT and MRI: | Intraoperative | Hydrocortisone |

Transsphenoidal | Improved | (41) |

|

|

|

| fusion | headache, |

| A mass in the

sellar | BP fluctuation | 300 mg/day | hypophysectomy | ptosis and |

|

|

|

|

| surgery | ophthalmalgia |

| fossa and

suprasellar |

|

|

| anisocoria |

|

|

|

|

| in prone | and ptosis |

| region,

compressing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| position | on right eye |

| the optic

chiasm |

|

|

|

|

|

| Goel et al,

2009 | 76/male | – | Elective left | Sudden | POD1 | CT: A mass in

the | Transient | Dexamethasone | Transnasal | Complete | (42) |

|

|

|

| total hip | headache, |

| left pituitary

fossa; | episode of | 2 mg/6 h | transphenoidal | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| athroplasty | total left

vision |

| MRI: Intersellar

mass | hypotension in |

| decompression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| loss and |

| with a

suprasellar | the

postoperative |

| of the

pituitary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| temporal right |

| extension on

the | period |

| tumor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| hemianopia |

| left side,

compressing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the optic

chiasma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and cavernous

sinus |

|

|

|

|

|

| Goel et al,

2009 | 61/male | – | Elective left | Sudden | POD1 | CT: An

intersellar | Microembolism | High-dose | Craniotomy and | Complete | (42) |

|

|

|

| total knee | headache, |

| tumor |

| dexamethasone | decompression | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| athroplasty | nausea, |

|

|

| intravenously | of pituitary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| vomiting, |

|

|

|

| adenoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| right ptosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kim et al,

2015 | 69/male | – | Open heart | Severe | After the | MRI: A sellar

mass | Excessive | High-dose |

Transsphenoidal | Complete | (43) |

|

|

|

| mitral | headache, | operation | with

hemorrhage |

anticoagulation, | steroids | resection of

the | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| valvuloplasty | visual field |

| pituitary | hemodynamic |

| tumor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| defects, |

| macroadenoma | instability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| double vision |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mizuno et

al, | 73/male | – | Elective | Right ptosis | 4 h after | CT and MRI: | Strong | – | Endonasal | Complete | (44) |

| 2011 |

|

| coronary | with

completely | the surgery | A large |

heparinization, |

|

transsphenoidal | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| artery bypass | dilated

pupils, |

| suprasellar

mass | BP fluctuation |

| resection of

the |

|

|

|

|

|

| grafting | light reflex |

| with bleeding | during CPB |

| pituitary

gland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| loss, headache |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Thurtell et

al, | 79/male | – | Coronary | Blindness, | Following | CT: A large

pituitary | Hemodilution, | Intravenous |

Transsphenoidal | Remained | (45) |

| 2008 |

|

| artery bypass | no light | extubation | mass; | hypotension, | dexamethasone | decompression | blind with |

|

|

|

|

| grafting | perception, |

| MRI: The mass |

anticoagulation | sodium |

| no light |

|

|

|

|

|

| miosis |

| extended into

the |

| phosphate 8 mg |

| perception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| suprasellar

cistern |

|

|

| on follow-up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and compressed

the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| optic chiasm |

|

|

|

|

|

| Thurtell et

al, | 64/male | – | Coronary | Blindness, | Following | CT: A large

pituitary | Hemodilution, | Intravenous |

Transsphenoidal | Remained | (45) |

| 2008 |

|

| artery bypass | no light | extubation | mass; | hypotension, | dexamethasone | decompression | blind with |

|

|

|

|

| grafting | perception, |

| MRI: The mass |

anticoagulation | sodium |

| no light |

|

|

|

|

|

| miosis |

| extended into

the |

| phosphate |

| perception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| suprasellar

cistern |

| 12 mg |

| on follow-up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and compressed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the optic

chiasm |

|

|

|

|

|

| Matsusaki et

al, | 56/female | – | Living donor | Headache, | POD10 | CT: A

high-density | Intraoperative | Prednisolone, | – | Complete | (46) |

| 2011 |

|

| liver trans- | thirst,

frequent |

| area in the

pituitary | hypotension, | 20 mg/days |

| recovery |

|

|

|

|

| plantation | urination |

| gland; | coagulopathy, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MRI: A

suspicious | transient |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| area between

the | hypertension, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| anterior and

posterior | dopamine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of the pituitary

gland | agonist

therapy |

|

|

|

|

| Telesca et

al, | 70/male | – | Elective | Headache, | Following | CT and MRI: A

sellar | – | High-dose | – | Complete | (47) |

| 2009 |

|

| coronary | visual field | extubation | mass with

suprasellar |

| steroids |

| recovery |

|

|

|

|

| bypass | defects, |

| extension |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| surgery | diplopia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fyrmpas et

al, | 67/male | Non- | Bilateral | Reduced | POD2 | CT and MRI: | Hypertension, | Corticosteroid | Microscopic | Regained | (23) |

| 2010 |

| secreting | endoscopic | vision, |

| Haemorrhage

within | diabetes, | replacement | endoscopic | vision and |

|

|

|

| pituitary | middle | diplopia, |

| the pituitary

tumor |

anticoagulation | therapy |

transsphenoidal | oculomotor |

|

|

|

| macro- | meatal | headache |

|

| therapy, |

| resection | nerve |

|

|

|

| adenoma | antrostomy, |

|

|

| prolonged |

|

| function |

|

|

|

|

| ethmoidec- |

|

|

| intraoperative |

|

| partly |

|

|

|

|

| tomy and |

|

|

| hypotension |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| polypectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Absalom et

al, | 61/male | Non- | Coronary | Sudden onset | 40 h after | CT: A 3-cm | Preoperative | Mannitol 80 g | Craniotomy,

de- | Dead of | (24) |

| 1993 |

| secreting | artery bypass | of headache, | the surgery | suprasellar

mass | anticoagulant | and | compression of | acute |

|

|

|

| pituitary | grafting | nausea, |

| with a large | therapy,

sudden | dexamethasone | the optic

nerves, | myocardial |

|

|

|

| tumor |

| vomiting |

| bleeding area

in | coronary | 10 mg iv | intracapsular | infarction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the pituitary |

revascularization |

| removal of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| pituitary

tumor |

|

|

| Madhusudhan | 62/male | – | Right total | Bilateral | POD5 | CT: A low | Preoperative | Hydrocortisone | – | Complete | (48) |

| et al,

2011 |

|

| shoulder | frontal |

| attenuation

signal | anticoagulant | and thyroxine |

| recovery |

|

|

|

|

| replacement | headaches, |

| in the

pituitary | therapy, | supplements, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| binocular |

| fossa; | postoperative | testosterone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| diplopia, |

| MRI: The

pituitary | hypoperfusion | replacement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| increased |

| stalk was

markedly |

| therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| urinary

output, |

| deviated to the

right |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| confusion, |

| with an

enhancing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| drowsiness |

| area in the

pituitary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| fossa, suggesting

an |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| adenoma |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cohen et

al, | 50/female | – | Liposuction | Persistent | After the | MRI: An

intrasellar | Large dose of | – |

Transsphenoidal | Complete | (49) |

| 2004 |

|

| on abdomen, | headache, | surgery | and suprasellar

mass | local

anesthetic, |

| resection of

the | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| hips and | nausea, |

| extending into

the | hypovolemia, |

| pituitary mass |

|

|

|

|

|

| thighs | vomiting |

| right cavernous

sinus | fluid overload |

|

|

|

|

| Shapiro, 1990 | 60/female | – | Coronary | Headache, | POD1 | CT: A

right-sided | Reduced | Hydrocortisone |

Transsphenoidal | Third nerve | (50) |

|

|

|

| artery bypass | severe right |

| sellar mass

with | perfusion | 50 mg every | surgery | palsy |

|

|

|

|

| surgery | ptosis, |

| extension into

the | pressure

during | 6 h |

| persisted |

|

|

|

|

|

| unresponsive |

| sphenoid

sinus; |

cardiopulmonary |

|

| post- |

|

|

|

|

|

| pupil on the |

| MRI: A

pituitary | bypass, |

|

| operatively |

|

|

|

|

|

| right side |

| tumor with

surroun- | anticoagulant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ding

hemorrhage | therapy |

|

|

|

|

| Tansel et

al, | 60/male | – | Coronary | Unexplained | Following | MRI: Pituitary | Protamine |

Hydrocortisone, | – | In good | (51) |

| 2010 |

|

| artery bypass | episodes of | extubation | infarction |

hypersensitivity | testosterone, |

| condition |

|

|

|

|

| grafting | hypotension, |

|

|

| thyroxin |

| except for |

|

|

|

|

|

| dysrhythmia, |

|

|

|

|

| a certain |

|

|

|

|

|

| electrolyte |

|

|

|

|

| degree of |

|

|

|

|

|

| imbalances, |

|

|

|

|

| visual |

|

|

|

|

|

| somnolence, |

|

|

|

|

| disturbance |

|

|

|

|

|

| agitation, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| respiratory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| distress, high |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| fever |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Slavin and | 57/male | – | Three-vessel | Mild

periorbital | Awakening | CT: An

intrasellar | Intraoperative |

Corticosteroids |

Transsphenoidal | Complete | (52) |

| Budabin, 1984 |

|

| coronary | pain, unable | from | mass with

right | or

postoperative |

| hypophysectomy | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| bypass | to open right | anesthesia | parasellar

extension | hypotension, |

|

| except for a |

|

|

|

|

| surgery | eye, headache |

|

|

anticoagulation, |

|

| mild visual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| positive

pressure |

|

| field defect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ventilation |

|

|

|

|

| Slavin and | 55/male | – | Mitral valve | Bilateral | After the | CT: An

intrasellar | Intraoperative |

Corticosteroids |

Transsphenoidal | Complete | (52) |

| Budabin, 1984 |

|

| replacement | blepharoptosis | surgery | mass with

large | or

postoperative |

| hypophysectomy | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| under cardio- | and partial

oph- |

| radiolucent

areas | hypotension, |

|

| except for |

|

|

|

|

| pulmonary | thalmoplegia |

| encroaching on

the |

anticoagulation, |

|

| a mild right |

|

|

|

|

| bypass | on each side, |

| right cavernous

sinus | positive

pressure |

|

| abduction |

|

|

|

|

|

| bilateral |

|

| ventilation |

|

| defect |

|

|

|

|

|

| confrontation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| visual fields |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| disclosed

nasal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| field defects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Present case, | 64/female | – | Extensive | Sudden onset | POD1 | CT: Multiple | Reduced

cerebral | Hormone | Microscopic | Complete | – |

| 2024 |

|

| stump | of headache, |

| lacunar

infarctions | perfusion, | replacement | endoscopic | recovery |

|

|

|

|

| cervicectomy, | drowsiness |

| and local

density | anticoagulant | therapy |

transsphenoidal | except for a |

|

|

|

|

| pelvic lymph |

|

| increase in

saddle | therapy |

| resection | mild blurry |

|

|

|

|

| node |

|

| and

suprasellar |

|

|

| vision |

|

|

|

|

| dissection |

|

| region; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MRI: The

pituitary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| was enlarged

and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| mixed signals

were |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| seen |

|

|

|

|

|

The diagnosis of PA is based on imaging evaluation,

mainly by MRI, which is more sensitive than CT. Pituitary MRI is

the radiological examination of choice (26). It can identify areas of bleeding and

necrosis and determine the relationship between the tumor and

neighboring structures, such as the optic chiasm, cavernous sinuses

and hypothalamus (27). However, CT

is also an examination that cannot be ignored, which can exclude

headaches caused by subarachnoid hemorrhage and make a tentative

diagnosis of intrasellar mass in most cases (28). In the present review, 80% of cases

were detected by CT and 80% by MRI.

Endocrine deficiencies can exist at the onset and

urgent evaluation of hormonal levels is suggested. According to the

latest guidelines from Oxford and Royal College of Physicians

(29), empirical hormonal

replacement is indicated in each patient with secondary adrenal

insufficiency no matter whether to perform a surgery or not.

Applying hydrocortisone 100–200 mg intravenously and then applying

either continuous intravenous infusion 2–4 mg/h or intramuscular

injection 50–100 mg/6 h are suggested. Reviewing the series of

patients with PA, 84% of cases received hormonal replacement

therapy regardless of whether surgery was performed, while 72% of

cases ended up receiving neurosurgical intervention. Applying

exogenous hormones alone has certain inherent imperfections, as

different hormones can influence the regulation of each other to a

certain extent (30). The

indications for surgery following hormonal replacement are as

follows: i) Evidence of worsening or persistent neurological

symptoms, such as visual impairment and ophthalmoplegia (paralysis

or weakness of the eye muscles); ii) altered mental state; iii)

patient is stable (no progressive deterioration in visual or mental

state) and shows improvement with conservative treatment (26). Most cases (84%) achieved partial or

complete remission in the visual field and ophthalmoplegia after

prompt treatment. However, most studies demonstrate that surgical

treatment, usually within 7 days of the event, leads to a higher

rate of recovery from visual impairment (31). Nevertheless, certain retrospective

studies confirm that there is no significant difference in the

recovery of vision and endocrine function between patients with

pituitary tumors treated conservatively and those undergoing

surgical decompression (32,33).

Currently, there is a lack of high-level evidence-based medical

evidence for choosing a treatment approach. The UK guidelines for

the management of pituitary tumor apoplexy recommend that the

treatment plan should be determined through multidisciplinary

collaboration, considering emergency surgical treatment based on

the patient's pituitary apoplexy score evaluation (9).

A limitation of this study was the omission of

ophthalmic assessment figures. These results were not included in

our hospital's electronic medical records. Consequently, only

copies of photographs of these results are available. Additionally,

paper reports were not preserved, precluding the possibility of

scanning them for enhanced clarity.

In conclusion, this review emphasized that even as

an uncommon postoperative complication, PA is potentially

life-threatening. It may occur in postoperative patients either

with diagnosed or undiagnosed prior pituitary adenoma. Early

diagnosis is essential for the timely treatment of hypopituitarism

and prevention of serious neurological complications. In short, the

wise surgeon should: i) Recognize PA after surgery in a timely

manner by obtaining early neuroimaging tests and pituitary-related

hormone tests and remember MRI is more sensitive than CT in

observing early changes of hemorrhage or infarction. ii) Take

initial action, such as applying intravenous glucocorticoids and

mannitol. Transsphenoidal surgery should be considered and

performed at the early stage of PA, if possible, to achieve better

recovery. iii) If vision and the visual field are not affected, or

vision defects are stable or temporary, hormonal replacement

therapy alone may be considered, which is more appropriate for

patients with surgical contraindications and may also spare

patients from unnecessary surgery.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KL and XY conceived the study and revised the

manuscript. CS made substantial contributions to the acquisition

and analysis of the data and drafted the tables of the manuscript.

LJ drafted the figures of the manuscript and interpreted the data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. XY and KL

checked and confirmed the authenticity of the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of this case report and accompanying

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ACTH

|

adrenocorticotropic hormone

|

|

BP

|

blood pressure

|

|

CT

|

computerized tomography

|

|

FSH

|

follicle-stimulating hormone

|

|

FT3

|

free triiodothyronine

|

|

FT4

|

free thyroxine

|

|

HPV

|

human papillomavirus

|

|

K+

|

potassium ion

|

|

LH

|

luteinizing hormone

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

Na+

|

sodium

|

|

PA

|

pituitary apoplexy

|

|

PET-CT

|

positron emission tomography-computed

tomography

|

|

POD

|

postoperative day

|

|

TCT

|

thinprep cytology test

|

|

TSH

|

thyroid stimulating hormone

|

References

|

1

|

Brougham M, Heusner AP and Adams RD: Acute

degenerative changes in adenomas of the pituitary body-with special

reference to pituitary apoplexy. J Neurosurg. 7:421–439. 1950.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Muthukumar N: Pituitary apoplexy: A

comprehensive review. Neurol India. 68:S72–S78. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bonicki W, Kasperlik-Załuska A, Koszewski

W, Zgliczyński W and Wisławski J: Pituitary apoplexy: Endocrine,

surgical and oncological emergency. Incidence, clinical course and

treatment with reference to 799 cases of pituitary adenomas. Acta

Neurochir (Wien). 120:118–122. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Verrees M, Arafah BM and Selman WR:

Pituitary tumor apoplexy: Characteristics, treatment, and outcomes.

Neurosurg Focus. 16:E62004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sibal L, Ball SG, Connolly V, James RA,

Kane P, Kelly WF, Kendall-Taylor P, Mathias D, Perros P, Quinton R

and Vaidya B: Pituitary apoplexy: A review of clinical

presentation, management and outcome in 45 cases. Pituitary.

7:157–163. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lubina A, Olchovsky D, Berezin M, Ram Z,

Hadani M and Shimon I: Management of pituitary apoplexy: Clinical

experience with 40 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 147:151–157.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Capatina C, Inder W, Karavitaki N and Wass

JA: Management of endocrine disease: Pituitary tumour apoplexy. Eur

J Endocrinol. 172:R179–R190. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bills DC, Meyer FB, Laws ER Jr, Davis DH,

Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW, Ilstrup DM and Abboud CF: A

retrospective analysis of pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery.

33:602–609. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bujawansa S, Thondam SK, Steele C,

Cuthbertson DJ, Gilkes CE, Noonan C, Bleaney CW, Macfarlane IA,

Javadpour M and Daousi C: Presentation, management and outcomes in

acute pituitary apoplexy: A large single-centre experience from the

United Kingdom. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 80:419–424. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dubuisson AS, Beckers A and Stevenaert A:

Classical pituitary tumour apoplexy: Clinical features, management

and outcomes in a series of 24 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg.

109:63–70. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nawar RN, AbdelMannan D, Selman WR and

Arafah BM: Pituitary tumor apoplexy: A review. J Intensive Care

Med. 23:75–90. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Randeva HS, Schoebel J, Byrne J, Esiri M,

Adams CB and Wass JA: Classical pituitary apoplexy: Clinical

features, management and outcome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf).

51:181–188. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ranabir S and Baruah MP: Pituitary

apoplexy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 15 (Suppl 3):S188–S196. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Briet C, Salenave S, Bonneville JF, Laws

ER and Chanson P: Pituitary apoplexy. Endocr Rev. 36:622–645. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pivonello R, De Leo M, Cozzolino A and

Colao A: The treatment of cushing's disease. Endocr Rev.

36:385–486. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mullur R, Liu YY and Brent GA: Thyroid

hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 94:355–382. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Hao G,

Zhang Z, Shao L, Tian Y, Dong Y, Zheng C, et al: Status of

hypertension in China: Results from the China hypertension survey,

2012–2015. Circulation. 137:2344–2356. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kelly AM: The minimum clinically

significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not

differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J. 18:205–207. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Reith FC, Van den Brande R, Synnot A,

Gruen R and Maas AI: The reliability of the Glasgow Coma Scale: A

systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 42:3–15. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Noh S and Kim SH, Cho NH and Kim SH: Rapid

reticulin fiber staining method is helpful for the diagnosis of

pituitary adenoma in frozen section. Endocr Pathol. 26:178–184.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shaikh AA, Williams DM, Stephens JW,

Boregowda K, Udiawar MV and Price DE: Natural history of pituitary

apoplexy: A long-term follow-up study. Postgrad Med J. 99:595–598.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Johnston PC, Hamrahian AH, Weil RJ and

Kennedy L: Pituitary tumor apoplexy. J Clin Neurosci. 22:939–944.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fyrmpas G, Constantinidis J, Foroglou N

and Selviaridis P: Pituitary apoplexy following endoscopic sinus

surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 124:677–679. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Absalom M, Rogers KH, Moulton RJ and Mazer

CD: Pituitary apoplexy after coronary artery surgery. Anesth Analg.

76:648–649. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Suri H and Dougherty C: Presentation and

management of headache in pituitary apoplexy. Curr Pain Headache

Rep. 23:612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Barkhoudarian G and Kelly DF: Pituitary

apoplexy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 30:457–463. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hong CS and Omay SB: Pituitary Apoplexy. N

Engl J Med. 387:23662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Goyal P, Utz M, Gupta N, Kumar Y, Mangla

M, Gupta S and Mangla R: Clinical and imaging features of pituitary

apoplexy and role of imaging in differentiation of clinical mimics.

Quant Imaging Med Surg. 8:219–231. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rajasekaran S, Vanderpump M, Baldeweg S,

Drake W, Reddy N, Lanyon M, Markey A, Plant G, Powell M, Sinha S

and Wass J: UK guidelines for the management of pituitary apoplexy.

Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 74:9–20. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Feldt-Rasmussen U, Klose M and Benvenga S:

Interactions between hypothalamic pituitary thyroid axis and other

pituitary dysfunctions. Endocrine. 62:519–527. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Abdulbaki A and Kanaan I: The impact of

surgical timing on visual outcome in pituitary apoplexy: Literature

review and case illustration. Surg Neurol Int. 8:162017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ayuk J, McGregor EJ, Mitchell RD and

Gittoes NJ: Acute management of pituitary apoplexy-surgery or

conservative management? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 61:747–752. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gruber A, Clayton J, Kumar S, Robertson I,

Howlett TA and Mansell P: Pituitary apoplexy: Retrospective review

of 30 patients-is surgical intervention always necessary? Br J

Neurosurg. 20:379–385. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mura P, Cossu AP, Musu M, De Giudici LM,

Corda L, Zucca R and Finco G: Pituitary apoplexy after laparoscopic

surgery: A case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 18:3524–3527.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

McClain IJ and Skidd PM: Case of pituitary

apoplexy after surgery. J Neuroophthalmol. 42:e385–e386. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liberale G, Bruninx G, Vanderkelen B,

Dubois E, Vandueren E and Verhelst G: Pituitary apoplexy after

aortic abdominal aneurysm surgery: A case report. Acta Chir Belg.

106:77–80. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Naito Y, Mori J, Tazoe J, Tomida A, Yagyu

S, Nakajima H, Iehara T, Tatsuzawa K, Mukai T and Hosoi H:

Pituitary apoplexy after cardiac surgery in a 14-year-old girl with

Carney complex: A case report. Endocr J. 66:1117–1123. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hidiroglu M, Kucuker A, Ucaroglu E,

Kucuker SA and Sener E: Pituitary apoplexy after cardiac surgery.

Ann Thorac Surg. 89:1635–1637. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yakupoglu H, Onal MB, Civelek E, Kircelli

A and Celasun B: Pituitary apoplexy after cardiac surgery in a

patient with subclinical pituitary adenoma: Case report with review

of literature. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 44:520–525. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yoshino M, Sekine Y, Koh E, Hata A and

Hashimoto N: Pituitary apoplexy after surgical treatment of lung

cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 98:1830–1832. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Joo C, Ha G and Jang Y: Pituitary apoplexy

following lumbar fusion surgery in prone position: A case report.

Medicine (Baltimore). 97:e06762018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Goel V, Debnath UK, Singh J and Brydon HL:

Pituitary apoplexy after joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty.

24:826.e7–10. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kim YH, Lee SW, Son DW and Cha SH:

Pituitary apoplexy following mitral valvuloplasty. J Korean

Neurosurg Soc. 57:289–291. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mizuno T: Pituitary apoplexy with third

cranial nerve palsy after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting.

Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 13:240–242. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Thurtell MJ, Besser M and Halmagyi GM:

Pituitary apoplexy causing isolated blindness after cardiac bypass

surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 126:576–578. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Matsusaki T, Morimatsu H, Matsumi J,

Matsuda H, Sato T, Sato K, Mizobuchi S, Yagi T and Morita K:

Pituitary apoplexy precipitating diabetes insipidus after living

donor liver transplantation. J Anesth. 25:108–111. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Telesca M, Santini F and Mazzucco A:

Adenoma related pituitary apoplexy disclosed by ptosis after

routine cardiac surgery: Occasional reappearance of a dismal

complication. Intensive Care Med. 35:185–186. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Madhusudhan S, Madhusudhan TR, Haslett RS

and Sinha A: Pituitary apoplexy following shoulder arthroplasty: A

case report. J Med Case Rep. 5:2842011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Cohen A, Kishore K, Wolansky L and Frohman

L: Pituitary apoplexy occurring during large volume liposuction

surgery. J Neuroophthalmol. 24:31–33. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Shapiro LM: Pituitary apoplexy following

coronary artery bypass surgery. J Surg Oncol. 44:66–68. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tansel T, Ugurlucan M and Onursal E:

Pituitary apoplexy following coronary artery bypass grafting:

Report of a case. Acta Chir Belg. 110:484–486. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Slavin ML and Budabin M: Pituitary

apoplexy associated with cardiac surgery. Am J Ophthalmol.

98:291–296. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|