Introduction

Cervical cancer ranks among the leading causes of

female cancer-associated mortality worldwide, especially in

low-income countries and populations from socioeconomically

disadvantaged areas, thereby posing a serious threat to women's

health (1,2). Surgery via radical hysterectomy and

systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy currently serves as the standard

treatment for early-stage cervical cancer. In recent decades,

minimally invasive approaches have become increasingly accepted and

implemented in the global management of early-stage gynecologic

cancer. Philp et al (3)

previously compared the safety, morbidity and survival outcomes of

abdominal radical hysterectomy (ARH) and laparoscopic radical

hysterectomy (LRH), revealing lower short-term morbidity and

similar survival outcomes in the LRH group compared with ARH

(3). Jensen et al (4) revealed that the adoption of robotic

minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for early-stage cervical cancer

was not associated with increased risk of recurrence or a reduction

in survival outcomes.

Prior to 2016, our gynecological departments

(Department of Gynecology, Jinhua Maternity and Child Health Care

Hospital, and Department of Gynecology, Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang

University; both Jinhua, China) used minimally invasive methods

with a uterine manipulator to perform radical surgery for cervical

cancer; however, since a number of cases of short-term central

recurrence were subsequently observed, the surgical approach was

revised. As of 2017, utilization of the uterine manipulator, myoma

drill and vaginal cuff was discontinued. Following this

modification, a notable decline in the incidence of central

recurrence was detected among patients. Notably, the Laparoscopic

Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial in 2018, which focused on

the oncological safety of MIS for early-stage cervical cancer,

indicated that the abdominal approach conferred a survival

advantage over MIS (5). In light of

these unexpected findings from the LACC trial, the majority of

gynecologic oncology centers across Europe and the United States

revised their clinical protocols regarding the management of women

with early-stage cervical cancer, reversing from minimally invasive

techniques to the previously established abdominal surgical

approach (6–8). In conventional MIS, the vagina is

accessed laparoscopically above the manipulator, which can lead to

exposure of the peritoneal cavity to tumor cells through

insufflation of carbon dioxide. Potential tumor spillage into the

peritoneal cavity may underlie the inferior outcomes of MIS.

However, given the advantages of laparoscopic surgery, a

significant number of patients select MIS as the preferred mode of

surgical treatment. Combined with data from our analysis of

patients with cervical cancer who underwent LRH showing a decreased

rate of tumor recurrence (Hu et al, unpublished data), the

current study provides a detailed evaluation of the oncologic

outcomes of patients with early cervical cancer undergoing

laparoscopic surgery incorporating protective methods to avoid

tumor spread with a median follow-up time of 51 months (range,

30–72 months) after surgery.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

This multicenter (Department of Gynecology, Jinhua

Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, and Department of

Gynecology, Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University) study involved

a retrospective analysis of patients diagnosed with cervical cancer

who received treatment at between January 2017 and June 2020.

Patients eligible for inclusion in the study were

those diagnosed with IA1 lymphovascular space invasion [LVSI (+)]

to IIA1 and IIIC1p cervical cancer [International Federation of

Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2018 (9)] who underwent LRH (type B-C). The

exclusion criteria included cases with tumor sizes >4 cm, a past

history of cervical colonization within 2 years, previous

chemotherapy or radiation, and conversion from MIS to laparotomy. A

total of 350 patients were identified who underwent LRH with

complete pelvic lymphadenectomy. All eligible patients were

informed of the potential complications, benefits and risks of both

ARH and LRH procedures before enrollment. The operating time was

recorded from the first skin incision to final closure. The tumor

diameter was determined with the aid of pelvic MRI scans. Operative

blood loss was estimated by collecting blood into suction bottles

during the surgical procedure.

Surgical techniques

All surgical interventions were conducted by five

proficient gynecologists. Patients were placed in the Trendelenburg

position at an angle of 30°. After general anesthesia, the vaginal

cuff was created in the upper third of the vaginal region for

patients with exophytic cervical cancer (tumor size >2 cm).

Subsequently, the laparoscopic procedure was conducted using five

trocars.

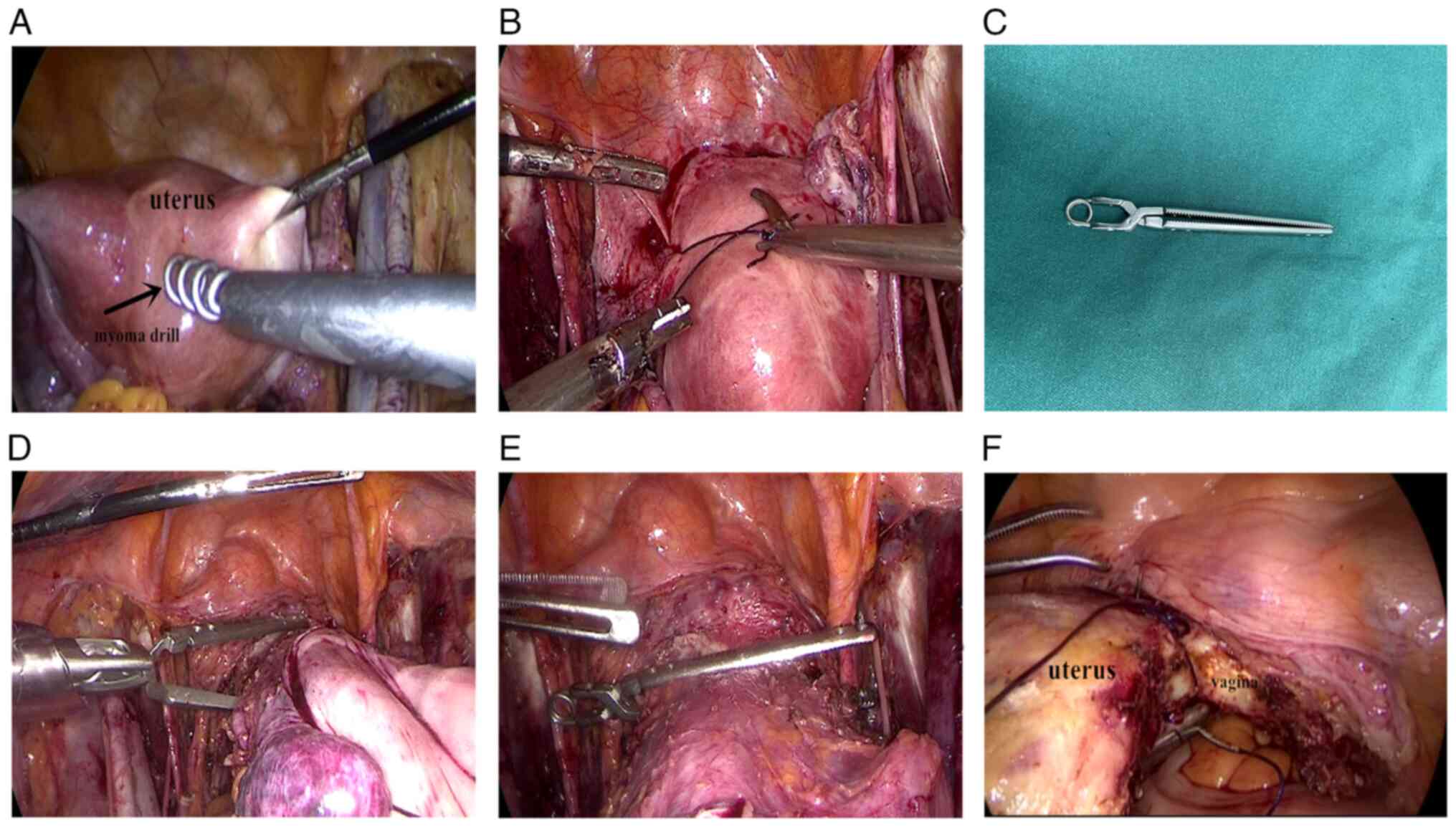

Initially, a myoma drill was applied (Fig. 1A) to grip the uterus for

manipulation purposes; however, to prevent uterine tearing, and

potential urologic and vascular complications associated with the

use of a myoma drill, the approach was modified to incorporate

thread fixation of the uterus (Fig.

1B), facilitating laparoscopic manipulation. During surgery,

the use of a uterine manipulator was avoided, while using the

remaining components of the MIS procedure. In addition, during the

operation, excised specimens, such as lymph nodes, were placed in a

specimen bag. In the final step before removal of the uterus, a

special clamp was used to secure the vaginal tube in cases of

endophytic type and ulcerative type cervical cancer (tumor size ≤2

cm; Fig. 1C-E). Cervical cancer

classification was based on clinical observations with ulcerative

type cervical cancer referring to cancerous tissue that developed

ulcers. To ensure that the clamp remained in place during the

surgery, both ends were fixed. During the later stages of the

process, vaginal suturing was performed (Fig. 1F) prior to colpotomy in patients

with smaller tumors (≤2 cm).

The steps incorporated (collection of excised

specimens in a specimen bag, vaginal cuffing, vaginal suturing and

clamping) were specifically designed to prevent tumor spillage

during laparoscopic procedures. Following colpotomy, the vaginal

cuff was secured above the special clamp, enabling the vaginal

delivery of the specimen. The specimens included the uterus,

fallopian tubes, a section of the vagina, parametrium and pelvic

lymph nodes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.) Data were summarized using descriptive

statistics. For time-to-event data, Kaplan-Meier estimates were

provided. The estimates of hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence

interval (CI) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards model,

and corresponding P-values were calculated using the log-rank test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Between January 2017 and June 2020, a total of 350

patients were recruited who were diagnosed with cervical cancer and

underwent radical hysterectomy for stages IA1 LVSI (+) to IIA1. The

baseline clinical characteristics of all patients are summarized in

Table I. Overall, 83 patients

(23.71%) were subjected to radiotherapy and/or adjuvant

chemoradiation. After radical hysterectomy, 53 patients underwent

brachytherapy and teletherapy, and 30 received chemotherapy

alongside brachytherapy and teletherapy. Over a median follow-up

period of 51 months (range, 30–72 months), five patients were lost

to follow-up and three refused treatment following surgery (these

patients were censored in the Kaplan-Meier analyses), the

disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival rates (OS) were

95.71% (335/350) and 98.86% (346/350), respectively. The

peri-operative outcomes of the study population are summarized in

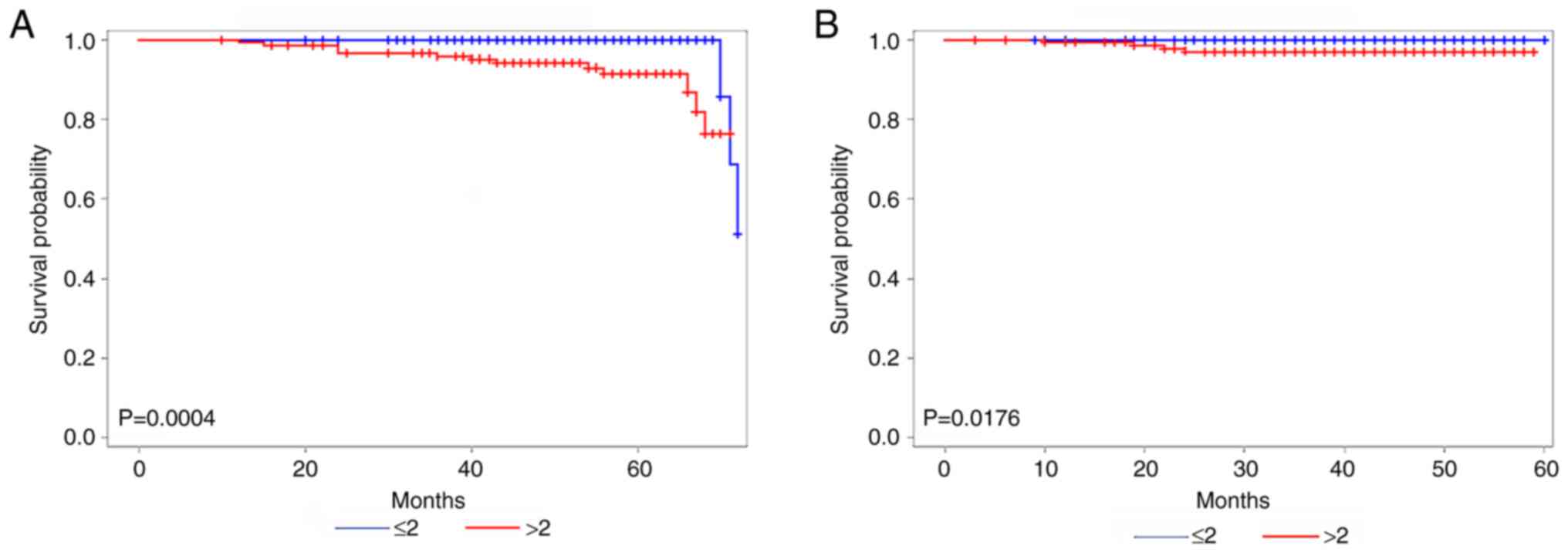

Table II. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier

curves are illustrated in Fig. 2A and

B. In the subgroup of 201 patients with tumor sizes ≤2 cm,

three relapses (1.49%) and no deaths were recorded. Fig. 2A shows the DFS of patients with

tumors sized ≤2 and >2 cm; the patients with tumor sizes ≤2 cm

that underwent MIS had a reduced likelihood of relapse compared to

those with tumors >2 cm in size (HR, 0.110; 95% CI, 0.025–0.488;

P=0.0004). Fig. 2B shows the OS of

patients with tumors sized ≤2 and >2 cm; there was no

significant difference between the two groups (P=0.0176).

| Table I.Patient characteristics. |

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range) | 43 (25–70) |

| Median BMI,

kg/m2 (range) | 22.5 (19.2–25.3) |

| Histology, n (%) |

|

|

Squamous | 269 (76.86%) |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 75 (21.43%) |

|

Adenosquamous | 6 (1.71%) |

| FIGO stage, n

(%) |

|

| IA1 LVSI

(+) | 22 (6.29%) |

| IA2 | 36 (10.29%) |

| IB1 | 137 (39.14%) |

| IB2 | 126 (36.00%) |

| IIA1 | 14 (4.00%) |

|

IIIC1P | 15 (4.29%) |

| Tumor size, n |

|

| ≤2

cm | 201 |

| 2–4

cm | 149 |

| Conversion to

laparotomy | 0 |

| Grading, n |

|

| G1 | 101 |

| G2 | 192 |

| G3 | 57 |

| Table II.Peri-operative outcomes of the study

population. |

Table II.

Peri-operative outcomes of the study

population.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Median surgical time,

min (range) | 221 (181–265) |

| Median estimated

blood loss, ml (range) | 145 (50–250) |

| LVSI, n |

|

|

Negative | 270 |

|

Positive | 80 |

| Median number of

lymph nodes (range) | 25 (16–38) |

| Histology of lymph

nodes, n |

|

| Tumor

free | 335 |

| Tumor

involved | 15 |

| Post-operative

complications, n |

|

| Tumor

tissue exposed to pelvic cavity after closure | 0 |

| Poor

healing of vaginal stump | 0 |

| Lymphatic

complications | 0 |

| Positive pathological

examination of vaginal margin, n | 0 |

| Adjuvant therapy,

n |

|

|

Radiotherapy and/or

chemoradiotherapy | 83/350 |

| Median follow-up,

months (range) | 51 (30–72) |

| Recurrence, n | 15/350 |

| Death, n | 4/350 |

| Liver

cancer | 1/4 |

| Cervical

cancer | 3/4 |

Discussion

Radical hysterectomy is the standard surgical mode

of therapy for patients diagnosed with early-stage cervical cancer

(10). Previous studies have

suggested that LRH yields comparable oncologic outcomes to those

achieved with ARH (11–13). Similarly, Gallotta et al

(14) demonstrated that LRH

provides equivalent or superior intraoperative and short-term

postoperative outcomes compared with ARH. However, Sert et

al (15) and Kohler et

al (16) showed no significant

differences in the recurrence and survival rates between the two

approaches. The benefits associated with MIS have led to an

increasing preference for LRH in the management of cervical cancer.

In a meta-analysis by Wang et al (11) on 12 studies comparing LRH with open

radical hysterectomy (754 vs. 785 cases) for cervical cancer, no

significant differences in the 5-year OS and DFS rates were

observed between the two approaches. However, a phase III

randomized clinical trial conducted in 2018 reported that minimally

invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with lower rates of

DFS (3-year rate, 91.2 vs. 97.1%) and OS (3-year rate, 93.8 vs.

99.0%) compared with ARH (17). In

addition, several retrospective studies have demonstrated an

association of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy with shorter

survival compared with ARH (5,11,18);

the observed shorter survival outcomes could be attributed to a

number of factors, including a lower extent of resection, the level

of surgeon's experience or the use of a uterine manipulator. Kim

et al (19) observed no

significant differences in the frequency of positive margins and,

in most institutions, only individuals who had undergone several

years of supervised training with a long learning curve were

capable of effectively performing laparoscopic surgery. Therefore,

the use of a uterine manipulator may be more significantly

associated with decreased survival outcomes. Doo et al

(20) reported no statistical

difference in recurrence risk (P=0.22) and risk of death (P=0.18)

between ARH and robotic radical hysterectomy groups. These

conflicting data necessitate reconsideration of whether the

decision to abandon MIS is in the best interest of patients.

Since 2013, the Department of Gynecology of Jinhua

Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, and Department of

Gynecology, Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University has employed

minimally invasive radical hysterectomy with a uterine manipulator

as the preferred surgical procedure for early-stage cervical

cancer, reflecting the global shift towards minimal invasive

approaches worldwide. However, a number of cases involving tumors

with larger diameters displayed recurrence only ~1 year after

surgical treatment, regardless of subsequent radiotherapy and/or

chemotherapy, and the majority of these individuals died as a

result of central recurrence. Notably, one of the patients

experiencing two episodes of central recurrence underwent

laparoscopic surgery, and has survived for 11 years. Considering

the short-term central recurrence and poor prognosis of larger

tumors, it was considered that the issue of tumor exposure to the

peritoneum was insufficiently addressed. As of 2017, the strategy

for surgical treatment of early-stage cervical cancer was modified

and a list of ‘no-tumor’ principles was designed, with the aim of

improving patient survival while maintaining optimal quality of

life. To facilitate further promotion of the surgical approach of

abandoning the uterine manipulator in radical hysterectomy, a

proposal for a new project within our hospital has been

submitted.

Various strategies have been implemented to prevent

contamination of the peritoneal cavity in the current study, such

as application of a vaginal cuff prior to surgical intervention, as

well as the use of a special vaginal clamp and vaginal suture

before colpotomy, particularly in cases where the cervical tumor is

encased within the vagina. However, the use of the clamp is solely

restricted to endophytic type and ulcerative type cancer cases

displaying smaller tumors (≤2 cm) without vaginal invasion.

Notably, in accordance with the ‘no-tumor’ principle, the clamp

needs to be repositioned from the vagina to cervix to close the

vaginal canal. Failure to do so may mobilize tumor cells,

potentially resulting in metastasis. Given the limitations of clamp

usage, vaginal suture was performed prior to colpotomy in patients

with smaller tumors (≤2 cm). The process of vaginal suturing is

associated with an increased risk of mobilization of tumor cells;

however, subsequent investigation revealed no instances of central

recurrence in the present study. For tumors >2 cm, the vaginal

cuff technique was primarily used, which is capable of effectively

avoiding tumor spread; however, this procedure presents technical

challenges, particularly in patients where cervix exposure is

difficult, such as those who are obese or nulliparous (19). On the other hand, during the type C

procedure, an incision was made into the deep uterine vein around

the ureter and the vaginal wall was subsequently transected;

however, the position of the vaginal incision in laparoscopic

surgery may not always be consistent with the level of the vaginal

cuff, leading to positioning failure in colpotomy and challenges in

proceeding with the operation. Additionally, the use of the myoma

drill carries the risk of uterine perforation and subsequent damage

to pelvic vessels or ureters. Considering the possible

complications, the myoma drill approach was modified to a uterine

suture approach at a later period of the study.

In the present study, myoma drill or uterine suture

techniques were applied combined with protective vaginal closure

techniques, such as clamping, vaginal cuffing or vaginal suturing,

to avoid tumor spillage before colpotomy. In addition, the specimen

was placed in a collection bag to prevent tumor spillage and its

extraction was performed via the vaginal route. Based on the

pathological results, 83 (23.71%) patients received radiotherapy

and/or adjuvant chemoradiation. No central recurrences were

observed after a median follow-up of 51 months (range, 30–72

months), with favorable DFS and OS outcomes of 95.71% (335/350) and

98.86% (346/350), respectively. The survival outcomes in all

patients were comparable to the LACC trial laparotomy group (3-year

DFS and OS rates of 97.1 and 99% respectively), which could be

attributed to the techniques implemented for avoiding tumor

spillage. and evolving treatment approaches for cervical cancer.

Moreover, the subgroup of patients with tumors ≤2 cm that underwent

MIS had a significantly lower likelihood of relapse compared to

those with tumors >2 cm (P=0.0005). In contrast to the LACC

trial, the current study did not reveal inferior outcomes

associated with MIS. The strict principle of no contact with the

tumor during excision may be a significant contributory factor. In

addition, the lower percentage of lymph node positivity in all

cases (4.29 vs. 12.4%) and relatively short follow-up compared with

the LACC trial may have influenced the OS and DFS rates. Other

studies (4,21) have similarly shown that MIS does not

yield inferior oncological outcomes. For example, two cohort

studies in Denmark and Sweden (4,22)

demonstrated that a nationwide adoption of robot-assisted MIS for

cervical cancer did not negatively impact oncologic outcomes,

consistent with the current findings. While the follow-up duration

in the present study was relatively short, it is important to

highlight that at the time of analysis, 60.29% of cases (211/350)

had successfully reached the 4-year time point. From the

aforementioned results, it may be inferred that the laparotomy may

not be the most appropriate method for treating early-stage

cervical cancer and MIS approaches warrant further

consideration.

The current study has a number of limitations that

should be taken into consideration. The follow-up period was

relatively brief, with a median of 51 months. Moreover, this

investigation is an observational retrospective analysis and lacks

a control group. The results highlight the need for further

surveillance through new prospective randomized trials comparing

LRH free from manipulators with ARH, with the goal of achieving

optimal DFS over longer follow-up durations.

In conclusion, the procedure performed in the

present study avoided the use of a uterine manipulator and

implemented protective vaginal closure over the entire tumor to

minimize the risk of tumor spillage in MIS. The results indicated

no inferior oncologic outcomes, particularly in the subgroup of

patients with tumor sizes ≤2 cm.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MH conceived and designed the study. LiJ, LaJ and MS

acquired, analyzed and interpretated the data. LiJ and MH drafted

the article and revised it critically for important intellectual

content. LiJ and LaJ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University and Jinhua Maternity and

Child Health Care Hospital (ethics approval no. 2020-268). All

patients provided written informed consent before recruitment.

Patient consent for publication

All patients provided written informed consent for

publication of the images and data presented.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 70:7–30. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Casarin J, Buda A, Bogani G, Fanfani F,

Papadia A, Ceccaroni M, Malzoni M, Pellegrino A, Ferrari F, Greggi

S, et al: Predictors of recurrence following laparoscopic radical

hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: A multi-institutional

study. Gynecol Oncol. 159:164–170. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Philp L, Covens A, Vicus D, Kupets R,

Pulman K and Gien LT: Feasibility and safety of same-day discharge

after laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervix cancer. Gynecol

Oncol. 147:572–576. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jensen PT, Schnack TH, Frøding LP, Bjørn

SF, Lajer H, Markauskas A, Jochumsen KM, Fuglsang K, Dinesen J,

Søgaard CH, et al: Survival after a nationwide adoption of robotic

minimally invasive surgery for early-stage cervical cancer-a

population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 128:47–56. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, Lopez

A, Vieira M, Ribeiro R, Buda A, Yan X, Shuzhong Y, Chetty N, et al:

Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for

cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 379:1895–1904. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Charo LM, Vaida F, Eskander RN, Binder P,

Saenz C, McHale M and Plaxe S: Rapid dissemination of

practice-changing information: A longitudinal analysis of

real-world rates of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy before

and after presentation of the LACC trial. Gynecol Oncol.

157:494–499. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hillemanns P, Brucker S, Holthaus B, Lampe

B, Runnebaum I, Ulrich U, Wallwiener M, Solomayer E, Fehm T and

Tempfer C: Comment on the LACC trial investigating early-stage

cervical cancer by the uterus commission of the study group for

gynecologic oncology (AGO) and the study group for gynecologic

endoscopy (AGE) of the German society for gynecology and obstetics

(DGGG). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 78:766–767. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Park JY and Nam JH: How should gynecologic

oncologists react to the unexpected results of LACC trial? J

Gynecol Oncol. 29:e742018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, .

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Cervical Cancer,

Version 4. 2019.https://www2.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/gynecological/english/cervical.pdfDecember

30–2021

|

|

10

|

Cibula D, Pötter R, Planchamp F,

Avall-Lundqvist E, Fischerova D, Haie Meder C, Köhler C, Landoni F,

Lax S, Lindegaard JC, et al: The European society of gynaecological

oncology/European society for radiotherapy and oncology/European

society of pathology guidelines for the management of patients with

cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 28:641–655. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang YZ, Deng L, Xu HC, Zhang Y and Liang

ZQ: Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage

cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 15:9282015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nam JH, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM

and Kim YT: Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in

early-stage cervical cancer: Long-term survival outcomes in a

matched cohort study. Ann Oncol. 23:903–911. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen Y, Xu H, Li Y, Wang D, Li J, Yuan J

and Liang Z: The outcome of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and

lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: A prospective analysis of 295

patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 15:2847–2855. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gallotta V, Conte C, Federico A, Vizzielli

G, Gueli Alletti S, Tortorella L, Pedone Anchora L, Cosentino F,

Chiantera V, Fagotti A, et al: Robotic versus laparoscopic radical

hysterectomy in early cervical cancer: A case matched control

study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 44:754–759. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sert BM, Boggess JF, Ahmad S, Jackson AL,

Stavitzski NM, Dahl AA and Holloway RW: Robot-assisted versus open

radical hysterectomy: A multi-institutional experience for

early-stage cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 42:513–522. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Köhler C, Hertel H, Herrmann J, Marnitz S,

Mallmann P, Favero G, Plaikner A, Martus P, Gajda M and Schneider

A: Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with transvaginal closure of

vaginal cuff-a multicenter analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

29:845–850. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shah CA, Beck T, Liao JB, Giannakopoulos

NV, Veljovich D and Paley P: Surgical and oncologic outcomes after

robotic radical hysterectomy as compared to open radical

hysterectomy in the treatment of early cervical cancer. J Gynecol

Oncol. 28:e822017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, Keating NL,

Del Carmen MG, Yang J, Seagle BL, Alexander A, Barber EL, Rice LW,

et al: Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for

early-stage cervical cancer. New Engl J Med. 379:1905–1914. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kim SI, Cho JH, Seol A, Kim YI, Lee M, Kim

HS, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH and Song YS: Comparison of survival

outcomes between minimally invasive surgery and conventional open

surgery for radical hysterectomy as primary treatment in patients

with stage iB1-IIA2 cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 153:3–12. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Doo DW, Kirkland CT, Griswold LH, McGwin

G, Huh WK, Leath CA III and Kim KH: Comparative outcomes between

robotic and abdominal radical hysterectomy for IB1 cervical cancer:

Results from a single high volume institution. Gynecol Oncol.

153:242–247. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Alfonzo E, Wallin E, Ekdahl L, Staf C,

Rådestad AF, Reynisson P, Stålberg K, Falconer H, Persson J and

Dahm-Kähler P: No survival difference between robotic and open

radical hysterectomy for women with early-stage cervical cancer:

Results from a nationwide population based cohort study. Eur J

Cancer. 116:169–177. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wenzel HHB, Smolders RGV, Beltman JJ,

Lambrechts S, Trum HW, Yigit R, Zusterzeel PLM, Zweemer RP, Mom CH,

Bekkers RLM, et al: Survival of patients with early-stage cervical

cancer after abdominal or laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: A

nationwide cohort study and literature review. Eur J Cancer.

133:14–21. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|