Introduction

The number of patients suffering from cancers

worldwide is increasing, and one of the most challenging issues in

oncology continues to be the problem of developing active drugs

economically and in a timely manner. In fact, the likelihood of

approval from pre-clinical discovery to phase I clinical trial is

lowest for oncology drugs (7%) compared with drugs for other

indications (1). Considering the

high cost and time-consuming nature of the clinical development of

oncology drugs, better pre-clinical platforms for drug screening

are urgently required.

Traditionally, the activity of anticancer drugs has

been evaluated in two-dimensionally (2D)-cultured cancer cell

lines. However, it is now being recognized that 2D-cultured cells

are unable to simulate the microenvironment of the original tumors,

which grow three-dimensionally (3D) (2–7). This

is speculated to be relevant to the fact that many drugs proving to

be clinically futile were pre-clinically evaluated to be ‘active’

using 2D-cultured cell line-based models. 3D-culture systems have

received attention as a means to avoid certain drawbacks of

2D-culture models, by recapitulating the tumor microenvironment, at

least in part (2–7).

In the present study, to investigate the utility of

3D-culture models in testing the activity of chemotherapeutic

drugs, we compared 2D- and 3D-culture of breast cancer cell lines

and primary cells obtained from a breast cancer patient and grown

as a patient-derived xenograft (PDX).

Materials and methods

Breast cancer cell lines and PDX

Two estrogen receptor

(ER)-positive/HER2-non-amplified (luminal-type; T-47D and

MCF-7), two ER-negative/HER2-amplified (HER2-type; BT-474

and HCC-1954) (8), and two

ER-negative/HER2-non-amplified (triple-negative type; BT-549

and MDA-MB-231) (8) breast cancer

cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection

(ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were maintained in

RPMI-1640® (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini-Bio-Products,

Inc., Woodland, CA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml

streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine. All cells were cultured at 37°C

in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and were in

logarithmic growth phase upon initiation of the experiments. The

cells were passaged for ≤3 months before fresh cells were obtained

from frozen early passage stocks received from the supplier.

The breast cancer tissue sample was collected from a

surgically resected primary tumor from a patient who underwent

surgery at Kobe University Hospital. The patient gave informed

consent for the research use of the tumor samples, as approved by

the Research Ethics Board at Kobe University Graduate School of

Medicine. The generation of PDX was as previously described

(9). In brief, the breast cancer

tissues were cut into fragments (~1 mm3 in size) using a

razor blade, and 4×106 cells were transplanted

orthotopically into inguinal mammary fat pad regions of female

NOD-SCID mice (Clea, Tokyo, Japan). When the size of the tumors

reached ~1–2 cm in diameter, the mice were sacrificed, and the

xenograft tumor was excised. In this study, a piece of fresh PDX

tissue originating from a luminal-type breast cancer tumor was

disag-gregated by automated mechanical method

(Medimachine®; Azone, Osaka, Japan). The primary cells

were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient

mixture F12® (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA)

supplemented with 2% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml

streptomycin, and cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with

5% CO2. All animal experiments were carried out under

the approval of the Kobe University Medical School Animal Care and

Use Committee.

Drugs

Paclitaxel (PTX), doxorubicin (ADR), and

5-fluorouracil (5FU) were purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Stock

solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at

20°C. The drugs were diluted in fresh media before each experiment,

with final DMSO concentrations <0.1%.

Drug sensitivity test

Cells (100 μl/well, n=6) were plated (day 0) in 2D

plates [Falcon 96-well Tissue Culture Plate® (353072);

Corning Inc., NY, USA] or 3D plates [NanoCluture 96-well

Plate® (NCP-LH-96); SCIVAX, Kanagawa, Japan]. The

numbers of cells seeded per well were as follows (determined in a

preparatory experiment): BT-474, 5,000 (2D) and 15,000 cells/well

(3D); T-47D, MCF-7 and BT-549, 2,500 (2D) and 10,000 cells/well

(3D); HCC-1954, 1,000 (2D) and 5,000 cells/well (3D); MDA-MB-231,

500 (2D) and 2,500 cells/well (3D). Drugs were added on day 3. The

concentration of each drug was adjusted to achieve 0.1, 1 and 10×

the areas under the curve (AUC) obtained in clinical

pharmacokinetic studies (Table I)

(10). The number of viable cells

was evaluated using a CellTiter-Glo® luminescent assay

(Promega, Madison, WI, USA) on day 6. A series of bright field

images were recorded on days 0–6 using a BZ-X710®

inverted microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

| Table IDrug concentrations applied. |

Table I

Drug concentrations applied.

| Package insert

data | | | |

|---|

|

| | | |

|---|

| Drug name | Dose

(mg/m2) | Maximum drug

concentration (μg/ml) | AUC (μg·h/ml) | MW | Clinical dose for

breast cancer (mg/m2) | Estimated AUC

(μM·h) | Concentration for

cell exposure (1× of AUC, μM) |

|---|

| PTX | 180 | 4.47±1.29 | 16.46±3.76 | 853.91 | 175 | 13.66 | 0.19 |

| ADR | 50 | 8.70±2.73 | 62.40±40.7 | 579.98 | 60 | 43.35 | 0.60 |

| 5FU | - | - | 20–24 | 130.08 | - | 2.86 | 0.04 |

Protein extraction and western

blotting

Cells treated with PTX (1× the AUC, Table I) were washed once with ice-cold PBS

and scraped immediately after adding lysis buffer [20 mM Tris (pH

7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40] containing

protease and phosphatase inhibitors (100 mM NaF, 1 mM

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 2

mg/ml aprotinin, 5 mg/ml leupeptin). Cell lysates were centrifuged

at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet insoluble material, and

the supernatant protein extracts were collected. Aliquots of

protein extracts were separated by electrophoresis on precast 7.5%

polyacrylamide gels, followed by transfer to polyvinylidene

difluoride membranes. Membranes were probed with an antibody to

detect cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Asp214)(D64E10)

(1:1,000; #5625; Cell Signaling Technology Beverly, MA, USA), and

separately with a β-actin antibody (1:3,000; A1978; Sigma-Aldrich).

Each primary antibody was detected using Amersham ECL Plus Western

Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire,

UK).

Hypoxia assay

Cells in maintenance media were plated (day 0) in 2D

(Corning Inc.) or 3D 96-well plates (SCIVAX), as described above.

The hypoxia probe LOX-1® (SCIVAX) was added on day 3.

LOX-1 is a phosphorescent light-emitting iridium complex; its

phosphorescence, which is quenched by oxygen, and increases in

response to low levels of oxygen, can be monitored using a

fluorescence microscope (11). A

BZ-X710 microscope was used to record the fluorescence images on

day 4.

Histologic and immunohistochemical

examinations

Cells were harvested by scraping into 7.5% formalin.

On the following day, the sediment containing the cell button was

scooped out and processed into paraffin wax. The paraffin-embedded

cell button (cell block) was sectioned at a 4-μm thickness and

these were assessed immunohistochemically using the following

primary antibodies: Ki-67 (1:5; #IR626; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark),

caspase-3 (1:200; #NCL-CPP32; Leica-Novocastra, Newcastle upon

Tyne, UK), and caspase-8 (1:150; #NCL-CASP-8; Leica-Novocastra).

For antigen retrieval, a citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was used for 10

min at 100°C and 30 min cooling to room temperature. A MACH 2

Double Stain system (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA) was used to

detect antigen-antibody reactions, followed by brown coloring by

DAB staining. Appropriate positive controls were employed for all

conditions.

Results

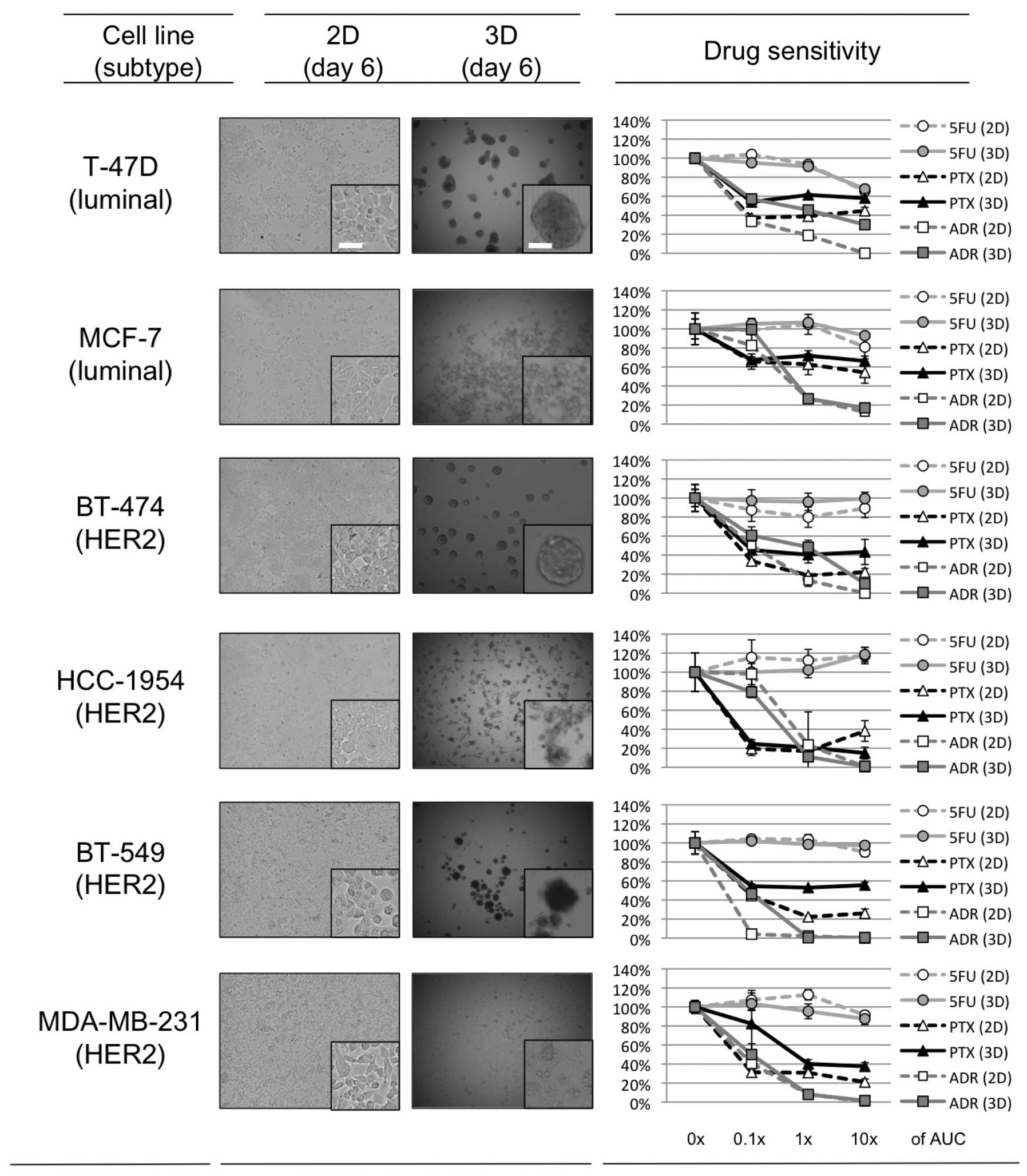

Spheroid formation in 3D-culture

Approximately one day after seeding on 3D-culture

plates, 3 of the 6 breast cancer cell lines, T47-D, BT-474 and

BT-549, started to form dense multicellular spheroids (MCSs). The

size of these MCSs plateaued ~3 days after seeding, and the maximal

size of the spheroids was ~200–300 μm for each of these cell lines.

For MCF-7, HCC-1954 and MDA-MB-231, the cells accumulated in the

3D-culture plates somewhat more than in the 2D-culture plates, and

although spheroids formed, they were looser than those produced by

the other 3 cell lines (Fig.

1).

Drug sensitivity in 2D- and

3D-culture

The relative growth rate of the 6 breast cancer cell

lines in the presence or absence of the 3 chemotherapeutic agents

(PTX, ADR, and 5FU) in 2D- or 3D-cell culture is shown in Fig. 1. The range of drug concentrations

used was set based on clinical pharmacokinetic data (0.1, 1, and

10× the AUC; Table I) in order to

explore the clinical relevance of the results. For 5FU, there was

no clear difference in sensitivity between the 2D- and 3D-culture

in any of the cell lines tested. The 3 cell lines that developed

dense 3D-MCSs (T-47D, BT-474 and BT-549) tended to show relative

resistance to PTX and ADR in the 3D-culture as compared to this

resistance in 2D. In contrast, the other 3 that developed loose

3D-spheroids (MCF-7, HCC-1954 and MDA-MB-231) tended to have

similar sensitivity to PTX and ADR in the 2D- and 3D-culture. These

findings confirm that the formation of dense MCSs in 3D-culture

plays a role in determining the sensitivity of the cell lines to

PTX and ADR.

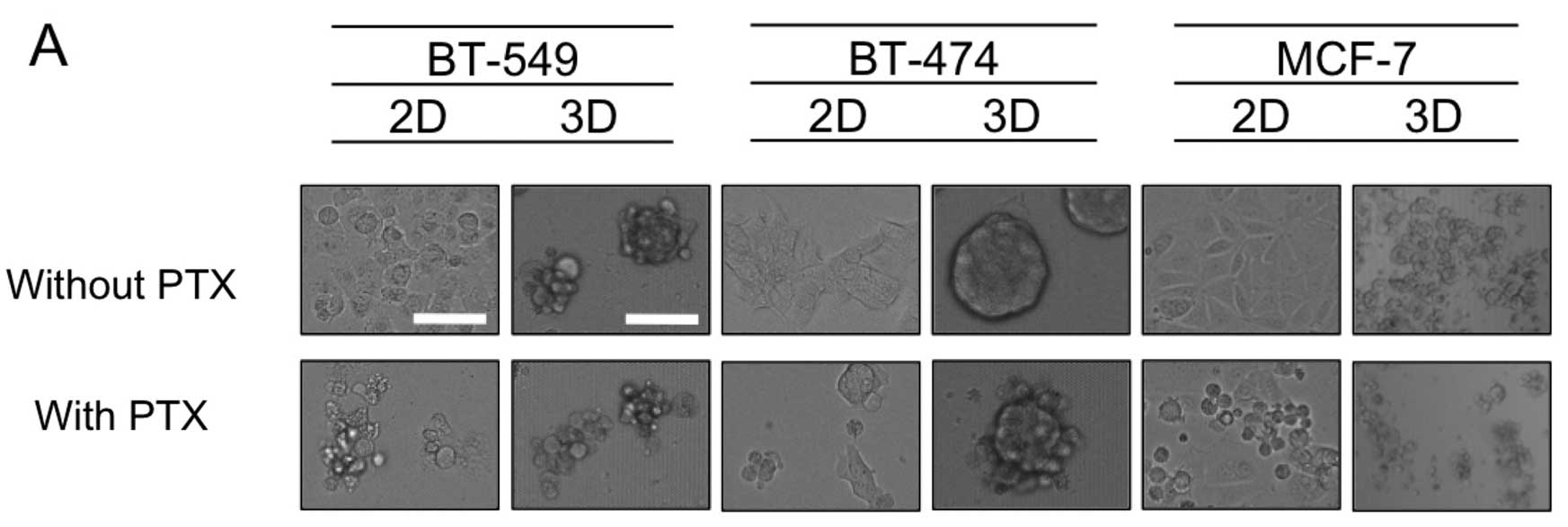

Apoptosis induced by PTX

To explore the mechanism of differential sensitivity

to PTX in the 2D- and 3D-cultures, 3 cell lines were subjected to

further study; BT-549 and BT-474 as representatives of cell lines

forming dense 3D-MCSs, and MCF-7 as an example of the loose 3D

phenotype. Fig. 2A shows that for

BT-549 and BT-474 cells, exposure to PTX (1× the AUC) resulted in

cell shrinkage, indicative of apoptosis when grown in 2D-culture,

yet dense 3D-MCSs remained in the 3D-cultures. The same PTX

treatment of MCF-7 cells yielded significant cell shrinkage in both

the 2D- and 3D-cultures (Fig. 2A).

Consistent with these findings, treatment of BT-549 or BT-474 cells

with PTX resulted in much smaller increases in cleaved PARP in the

3D-culture than in the 2D-culture, whereas in MCF-7 (with loose

MCSs) the same PTX treatment resulted in a similar degree of

increase in cleaved PARP (Fig. 2B).

These results confirmed that relative resistance to PTX in the cell

lines with dense MCSs in 3D-culture than in 2D-culture was in part

due to reduced apoptosis.

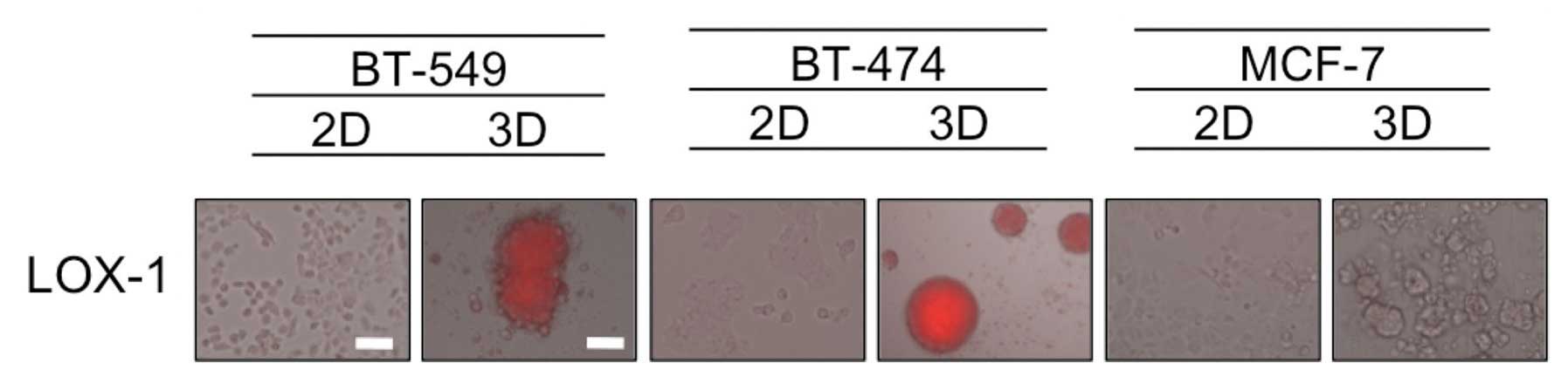

Hypoxia in dense MCSs

It has been speculated that the formation of dense

MCSs leads to hypoxia inside the spheroids mimicking in vivo

tumors, and hypoxia is known to be one of the factors associated

with resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs (12). Therefore, we evaluated the oxygen

status in 2D- and 3D-cultures by utilizing the hypoxia probe LOX-1,

that generates signals that are visible using a fluorescence

microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3,

hypoxic areas were observed inside the dense 3D-MCSs from the

BT-549 and BT-474 cell lines, but not in the loose spheroids formed

by MCF-7 cells or cells grown in 2D. These findings suggest that

the hypoxia status in dense 3D-MCSs may be one of the causes of

their drug resistance.

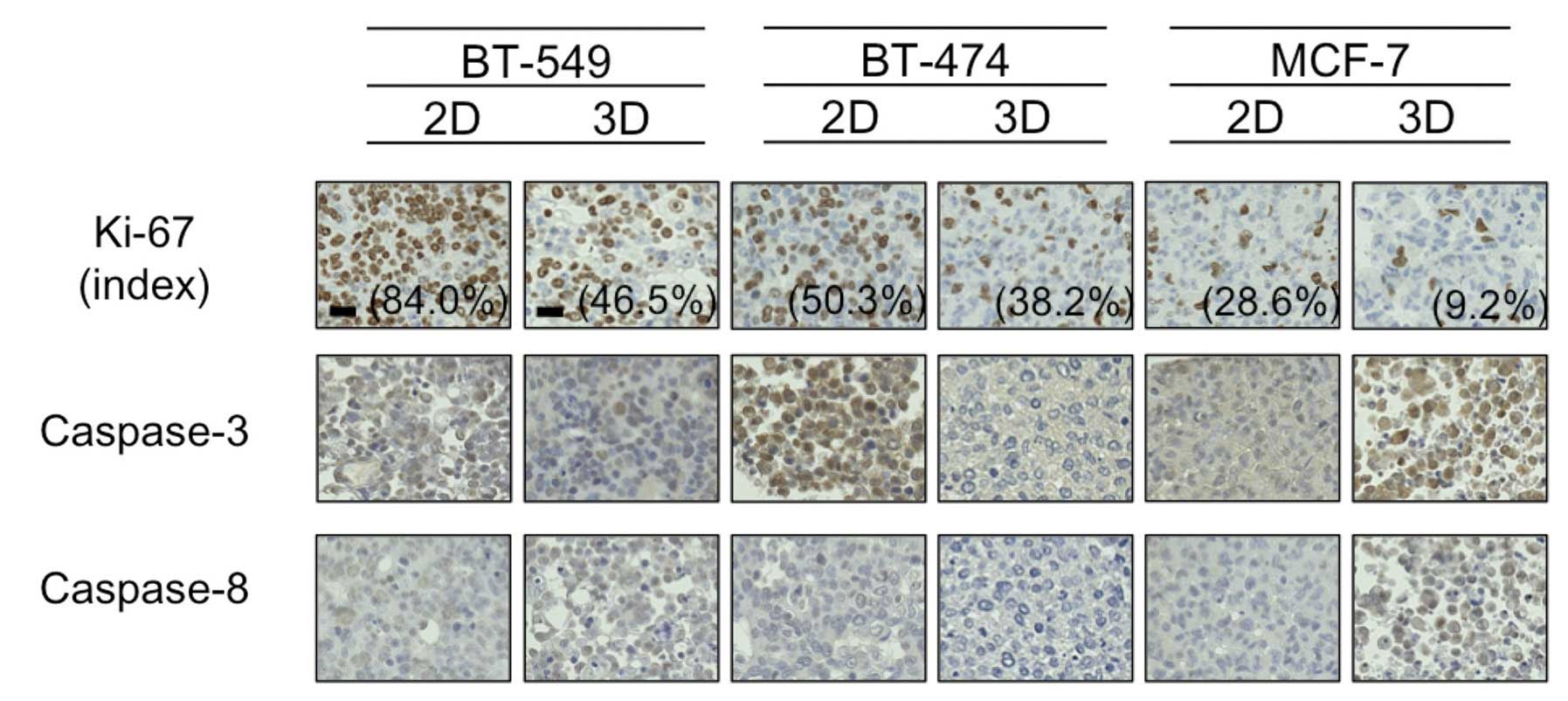

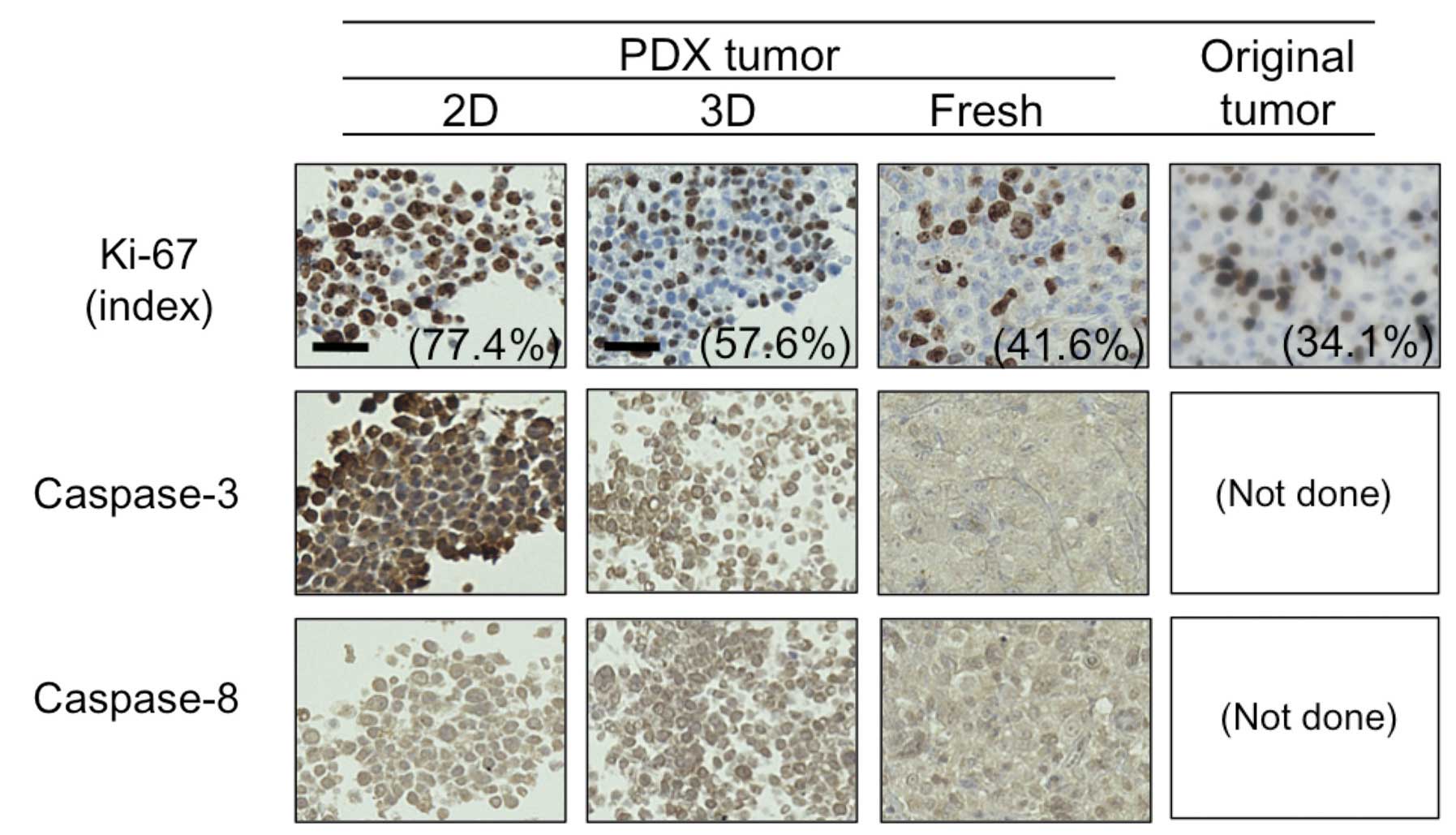

Ki-67 and caspase expression

Hypoxia has been reported to cause cancer cell

dormancy in the G0 phase (13),

thus we next evaluated staining using the antibody Ki-67, which is

reported to be positive in cells except for those in the G0 phase.

As shown in Fig. 4, the Ki-67 index

was higher in the 2D-culture than that in the 3D-culture for all 3

cell lines tested. The difference was particularly marked for the

BT-549 cells, which formed dense 3D-MCSs (84.0% Ki-67-positive

cells in 2D vs. 46.5% in 3D).

Following this, due to a study suggesting that

downregulation of caspase-3 and -8 in hypoxic conditions may

mediate resistance to PTX in breast cancer cells (14), we immunohistochemically evaluated

the expression of these proteins in 2D- and 3D-cultures. As shown

in Fig. 4, the expression levels of

caspase-3 and -8 were almost identical between the 2D- and

3D-cultures for all 3 cell lines tested, with the exception of

BT-474 cells, in which caspase-3 expression was much higher in the

2D-culture than this level in the 3D-culture. In addition,

caspase-3 was detected mainly in the nuclei of 2D-cultured BT-474

cells, indicative of active caspase-3. These findings suggested to

us that hypoxia in 3D-MCSs may lead to cell dormancy and/or

downregulation of caspase-3, and result in resistance to PTX.

The potential of the 3D-primary culture

to simulate tumor growth in vivo

To explore the relevance of a 3D-culture to tumor

growth in vivo, we compared an excised tumor and its 2D- and

3D-primary cultures in terms of expression of Ki-67, caspase-3, and

caspase-8. We utilized a PDX tumor for this purpose. As shown in

Fig. 5, the proportion of cells

positive for Ki-67 in the 2D- and 3D-primary cultured cells

originating from PDX, fresh PDX tumor, and the patient’s original

tumor were 77.4, 57.4, 41.6 and 34.1%, respectively. Moreover,

consistent with the BT-474 cells (Fig.

4), caspase-3 expression was much higher in the PDX tumor and

its 2D-primary culture than in its 3D-primary culture, whereas no

difference was observed in caspase-8 expression between the 2D- and

3D-culture. These findings confirm that a 3D-primary culture rather

than a 2D-primary culture may better indicate in vivo tumor

dormancy and anti-apoptotic features.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that certain

breast cancer cell lines formed dense 3D-MCSs, and the formation of

MCSs was associated with decreased sensitivity to chemotherapeutic

drugs (Fig. 1). Our data also

revealed that the drug resistance may be caused by hypoxia in MCSs,

which was associated with an increased cell population in the G0

phase and/or downregulation of proapoptotic molecules such as

caspase-3 (Figs. 2–4). Moreover, tumor dormancy observed in

the in vivo PDX tumor was better represented by its

3D-primary culture than its 2D-primary culture (Fig. 5).

2D-cultured cancer cell lines grown on plastic

surfaces are considered unable to precisely simulate tumor

conditions in vivo (2–7). It

may therefore, be predicted that the development of anticancer

drugs based on screening using 2D-cultured cell lines is not

efficient. The fact that numerous anticancer drugs are eliminated

during clinical development indicates that anticancer activity

tends to be overestimated on a 2D-culture-based screening platform.

In contrast, 3D-culture systems have been shown to better simulate

the in vivo tumor microenvironment than a 2D-culture

(3–7); several previous studies have shown

that 2D-cultured cells tended to overestimate the efficacies of

chemotherapeutic drugs compared with 3D-cultured cells (15–17).

Consistent with these studies, our present study showed that the

cell lines producing dense 3D-MCSs are more resistant to PTX and

ADR in a 3D- than in 2D-culture (Fig.

2A). When measuring PTX-induced apoptosis, this tendency was

even more apparent (Fig. 2B),

suggesting that the formation of 3D-MCSs may protect cells from

cell death. These findings suggest that a 3D-culture potentially

avoids the overestimation of antitumor efficacy observed in a

2D-culture. It is noteworthy that the phenomena were observed with

the clinically achievable drug concentrations calculated based on

the AUC in cancer patients, which were less than the maximum drug

concentrations (Cmax, Table I).

While drug concentrations around Cmax have conventionally been

employed for testing in in vitro experiments, these

concentrations may be inappropriate since Cmax does not persist for

hours in vivo (18).

Therefore, we believe that drugs which kill 3D-growing cells at

concentrations less than Cmax should be evaluated to be active.

Potential advantages of 3D-culture systems over

2D-culture systems are that only the former may feature oxygen

gradients which exist in in vivo tumors. Hypoxia is known to

cause drug resistance through several mechanisms. One conventional

mechanism is that of hypoxia-induced cell cycle arrest. Sullivan

et al demonstrated that hypoxia induced an increased G0

non-cycling population associated with etoposide resistance in

breast cancer cell lines (13).

Consistent with this result, one of the cell lines forming dense

MCSs in 3D, BT-549, had a much lower Ki-67 labeling index

(representing a greater G0 population) in the 3D than that in the

2D-cultured cells. However, another cell line that formed dense

3D-MCSs, BT-474, had only a slightly lower Ki-67 in 3D than in 2D,

with a difference of 12.1% (Fig.

4), which was actually smaller than that in MCF-7 cells which

formed only loose MCSs. This indicated that drug resistance

associated with dense 3D-MCSs could not always be attributable to

an increased G0-dormant cell population. Therefore, we evaluated

the expression of caspase-3 and -8, as the downregulation of these

two pro-apoptotic molecules, along with change in expression of

another six molecules, were identified to be potentially involved

in hypoxia-induced protection against PTX-induced apoptosis by a

previous study (14). Partially

consistent with this study, BT-474 expressed lower levels of

caspase-3 in the 3D- than in 2D-culture. Furthermore, we found that

tumor dormancy and downregulation of caspase-3 observed in the

original patient tumor and/or PDX tumor was better maintained in

the 3D-primary cultured cells than in the 2D-primary cultured cells

(Fig. 5). These findings suggest

that 3D-culture may provide a better drug screening platform; one

that produces more clinically relevant results.

Several limitations of our study warrant mention.

Firstly, this study was derived from the nature of an in

vitro model. At present, there are various 3D-culture systems

besides the one we used, yet none of them are considered to be a

standard method, and it is unclear which system is the most

clinically relevant (3–7). One clear observation is that

3D-culture of cell lines will never accurately, fully represent the

tumor microenvironment in vivo, because the latter have

interactions with stromal tissues or blood perfusions. Co-culture

with stromal cells or primary culture in 3D-conditions may

partially solve these issues and are under investigation in our

laboratory. Animal models such as PDXs are being evaluated as a

potential drug screening platform for the next generation (19–22),

however, difficulty in the development and expansion of the PDX

model, and their high-cost will preclude their use in

high-throughput screening. Therefore, refining 3D-culture systems

as drug screening platforms is worth driving forward. Secondly,

although our results support that hypoxia in 3D-culture may play a

role in drug resistance, we did not prove the underlying molecular

mechanisms of this in the present study. In addition, we did not

explore many other potential mechanisms of drug resistance induced

by hypoxia, such as enhanced drug efflux or autophagy, or

inhibition of senescence or DNA damage (12,23).

These mechanisms of hypoxia-induced drug resistance are reported to

be mediated mainly by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)

(12,24,25).

In our study, however, we were unable to detect HIF-1α with

immunohistochemistry or western blotting, even in dense MCSs (data

not shown).

In conclusion, 3D-cultured breast cancer cells show

relative drug resistance as compared to 2D-cultured cells when

forming dense 3D-MCSs, and the resistance is associated with

hypoxia. 3D-MCSs could be utilized as an in vitro cell-based

drug-testing platform.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Megumi Izumi and staffs of Kobe

University Hospital Advanced Tissue Staining Center (KATS) for

their excellent technical support. This study was supported by the

Global Centers of Excellence Program (H.M.), Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) (T.M.), and by a Research Grant from the

Takeda Science Foundation (T.M).

References

|

1

|

Hay M, Thomas DW, Rosenthal J, et al:

Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat

Biotechnol. 32:40–51. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yamada KM and Cukierman E: Modeling tissue

morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell. 130:601–610. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hirschhaeuser F, Menne H, Kunz-Schughart

LA, et al: Multicellular tumor spheroids: an underestimated tool is

catching up again. J Biotechnol. 148:3–15. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rimann M and Graf-Hausner U: Synthetic 3D

multicellular systems for drug development. Curr Opin Biotechnol.

23:803–809. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Breslin S and O’Driscoll L:

Three-dimensional cell culture: the missing link in drug discovery.

Drug Discov Today. 18:240–249. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lovitt CJ, Shelper TB and Avery VM:

Advanced cell culture techniques for cancer drug discovery.

Biology. 3:345–367. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Weigelt B, Ghajar CM and Bissell MJ: The

need for complex 3D culture models to unravel novel pathways and

identify accurate biomarkers in breast cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

69–70:42–51. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lacroix M and Leclercq G: Relevance of

breast cancer cell lines as models for breast tumours: an update.

Breast Cancer Res Treat. 83:249–289. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nobutani K, Shimono Y, Takai Y, et al:

Absence of primary cilia in cell cycle-arrested human breast cancer

cells. Genes Cells. 19:141–152. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gamelin E, Delva R, Jacob J, et al:

Individual fluorouracil dose adjustment based on pharmacokinetic

follow-up compared with conventional dosage: results of a

multicenter randomized trial of patients with metastatic colorectal

cancer. J Clin Oncol. 26:2099–2105. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang S, Hosaka M, Yoshihara T, et al:

Phosphorescent light-emitting iridium complexes serve as a

hypoxia-sensing probe for tumor imaging in living animals. Cancer

Res. 70:4490–4498. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rohwer N and Cramer T: Hypoxia-mediated

drug resistance: novel insights on the functional interaction of

HIFs and cell death pathways. Drug Resist Updat. 14:191–201. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sullivan R and Graham CH: Hypoxia prevents

etoposide-induced DNA damage in cancer cells through a mechanism

involving hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cancer Ther. 8:1702–1713.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Flamant L, Notte A, Michiels C, et al:

Anti-apoptotic role of HIF-1 and AP-1 in paclitaxel exposed breast

cancer cells under hypoxia. Mol Cancer. 9:1912010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Karlsson H, Fryknas M, Nygren P, et al:

Loss of cancer drug activity in colon cancer HCT-116 cells during

spheroid formation in a new 3-D spheroid cell culture system. Exp

Cell Res. 318:1577–1585. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Vinci M, Gowan S, Boxall F, et al:

Advances in establishment and analysis of three-dimensional tumor

spheroid-based functional assays for target validation and drug

evaluation. BMC Biol. 10:292012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lee JM, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Lee N, et al:

A three-dimensional microenvironment alters protein expression and

chemosensitivity of epithelial ovarian cancer cells in vitro. Lab

Invest. 93:528–542. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

No authors listed. Dishing out cancer

treatment. Nat Biotechnol. 31:852013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Marangoni E, Vincent-Salomon A, Auger N,

et al: A new model of patient tumor-derived breast cancer

xenografts for preclinical assays. Clin Cancer Res. 13:3989–3998.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cottu P, Marangoni E, Assayag F, et al:

Modeling of response to endocrine therapy in a panel of human

luminal breast cancer xenografts. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

133:595–606. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang X, Claerhout S, Prat A, et al: A

renewable tissue resource of phenotypically stable, biologically

and ethnically diverse, patient-derived human breast cancer

xenograft models. Cancer Res. 73:4885–4897. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fong EL, Martinez M, Yang J, et al:

Hydrogel-based 3D model of patient-derived prostate xenograft

tumors suitable for drug screening. Mol Pharm. 11:2040–2050. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Housman G, Byler S, Sarkar S, et al: Drug

resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers. 6:1769–1792. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li J, Shi M, Cao Y, et al: Knockdown of

hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells

results in reduced tumor growth and increased sensitivity to

methotrexate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 342:1341–1351. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Doublier S, Belisario DC, Sapino A, et al:

HIF-1 activation induces doxorubicin resistance in MCF7 3-D

spheroids via P-glycoprotein expression: a potential model of the

chemoresistance of invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the breast.

BMC Cancer. 12:4–18. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|