Introduction

Angiogenesis plays an essential role in promoting

tumor growth. Tumor development beyond 1–2 mm is dependent on the

formation of a functional blood supply system for nutrient delivery

(1–3). Based on previous studies involving

intact established cell lines or vessels, the blood vessels of

tumors and those of normal tissues differ in regards to

permeability, composition of the basement membrane, extracellular

matrix and cellular composition. When compared to normal blood

vessels, tumor vessels are tortuous, exhibit poorly organizational

characteristics, high permeability and are inclined to leak

allowing macromolecules of the tumor microenvironment into blood

circulation (4–6). The study of the mechanism of the

development of tumor blood vessels plays a major role in tumor

diagnosis and therapy. However, endothelial cells (ECs) comprise

only 1–2% of the total amount of tumor tissues, and they are

embedded in matrix components and tightly surrounded by various

other cell types (7). Therefore, it

is particularly difficult to isolate endothelial cells from tumor

tissues.

In recent years, purification of ECs for culture and

molecular profiling has gained more and more interest, and

different techniques have been employed (8–10).

However, these techniques are all prone to obtain a mixed sample

with unwanted cells. This study reports a new purification method

by which to obtain numerous endothelial cells in superior

conditions.

Materials and methods

Cells and animals

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Vital River Company

(Beijing, China) and were housed and cared for in accordance with

the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Association

guidelines, and all protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics

Committee of Guangxi Medical University (Nanning, Guangxi, China).

Mouse lung carcinoma cells (Lewis) (1×106) were injected

into the right flank of mice. Tumors were excised for study 45 days

after injection.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were

utilized. Dewaxed sections of Hep1–6 xenografts were blocked with

3% hydrogen peroxide and 10% normal serum from the secondary

antibody species, and then incubated at 4°C with the primary

antibody mCD105 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight. This was then

followed by biotin labeled secondary antibody for 30 min and

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated ultrastreptavidin-labeling

reagent for 30 min. Color was developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine

(DAB) solution.

Endothelial cell isolation

Tumors were removed and placed in cold PBS solution

with 50 U/ml heparin. Peripheral and necrotic tissues were excised

and the remaining tumor was minced using a scalpel. Dissociation of

0.1×0.1×0.1 cm3 minced tissue was performed in an enzyme

cocktail of 10 mg collagenase type I, 20 ml Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (DMEM) and 2 ml FBS at room temperature for 60 min

of constant mixing with a vortex. The cell suspension was passed

through 80 mesh strainer, washed with PBS solution, and then the

cells were resuspended in 100 µl buffer [PBS (pH 7.2), 0.5%

FBS, 2 nM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]. Single cells were

magnetically labeled with anti-CD105 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec,

Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) in the dark at 4°C for 30 min and

applied to the prepared MS Column (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch

Gladbach). CD105− cells were collected in the

flow-through of the column, while CD105+ cells bound to

the beads were flushed out by applying the plunger supplied with

the column. Sorted CD105+ cells were plated into 6-well

plates and cultured in endothelial cell medium (ScienCell,

USA).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

(FACS)

For flow cytometry, the cells were stained at the

concentration of 1×106 cells/90 µl buffer and 10

µl phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD105 (eBioscience, San

Diego, CA, USA) at 4°C for 25 min before FACS analysis. All data

were analyzed by EXPO32 software.

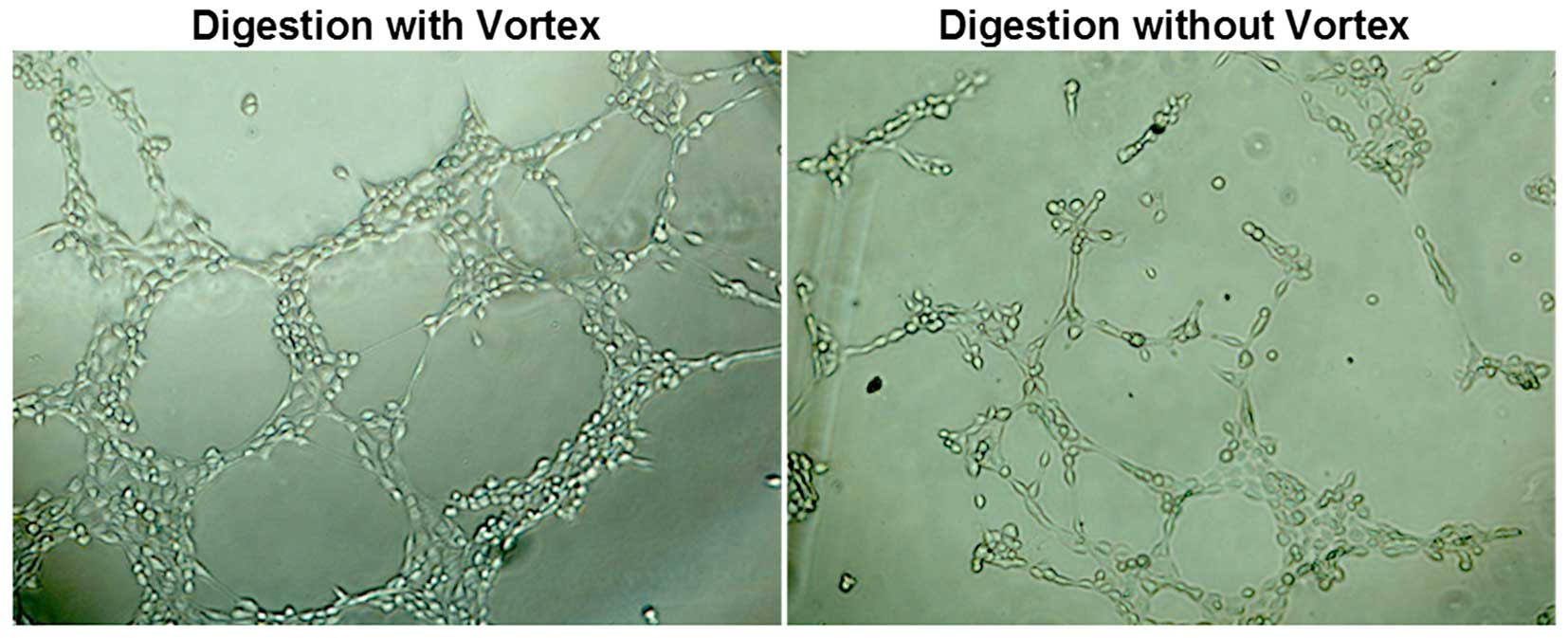

Tube formation assay

To analyze the capillary-like tube formation ability

of CD105+ cells, 50 µl/well of growth

factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was

laid into 96-well plates to solidify. Cells were seeded into

96-well plates. After 12 h, the tube formation was assessed with

microscopy.

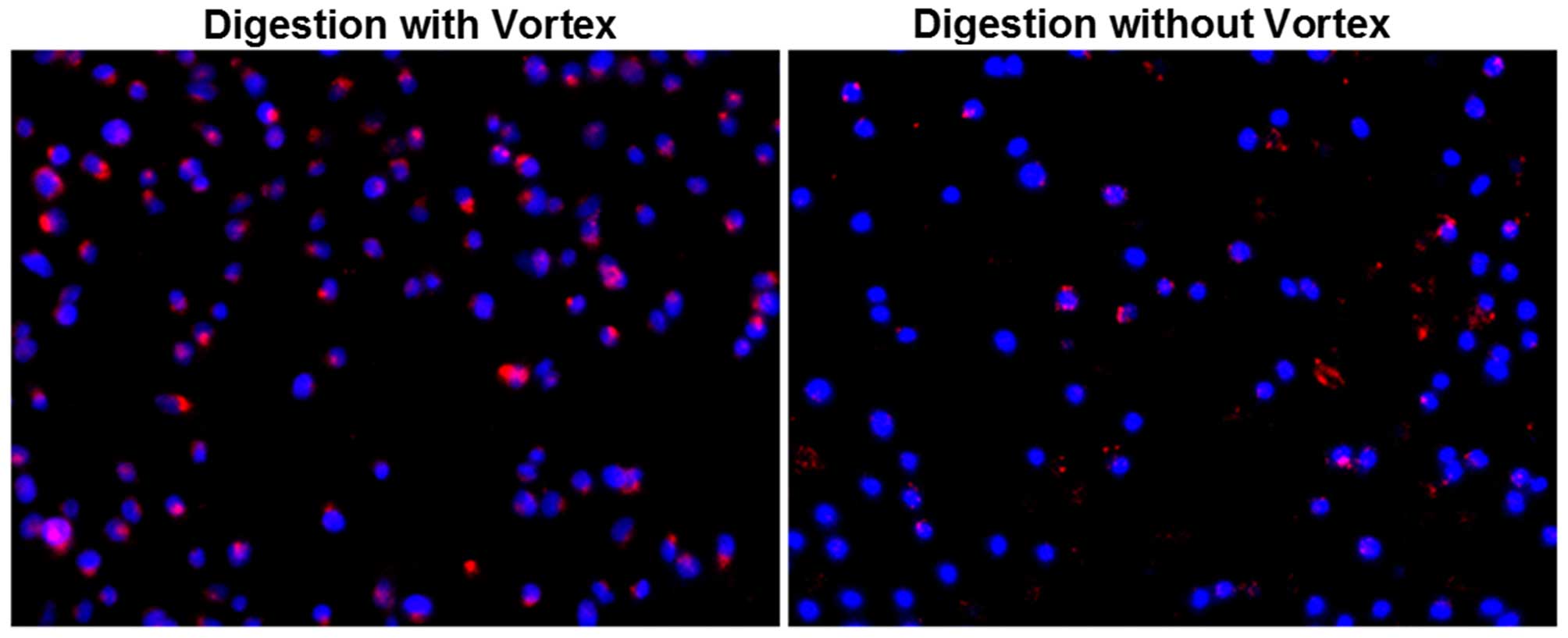

Dil-Ac-LDL uptake assay

CD105+ cells were plated into 6-well

plates at 5×104 cells/dish. At 75% confluency, the

culture medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM for 24 h, followed

by incubation with 2 µg/ml Dil-ac-LDL for 5 h at 37°C in 5%

CO2. Then, the cells were washed and fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min, followed by DAPI staining for 3

min. The Dil-ac-LDL uptake was assessed using microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The significance

of differences between groups was assessed by a t-test. All

analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism program version 5

(GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant result.

Results

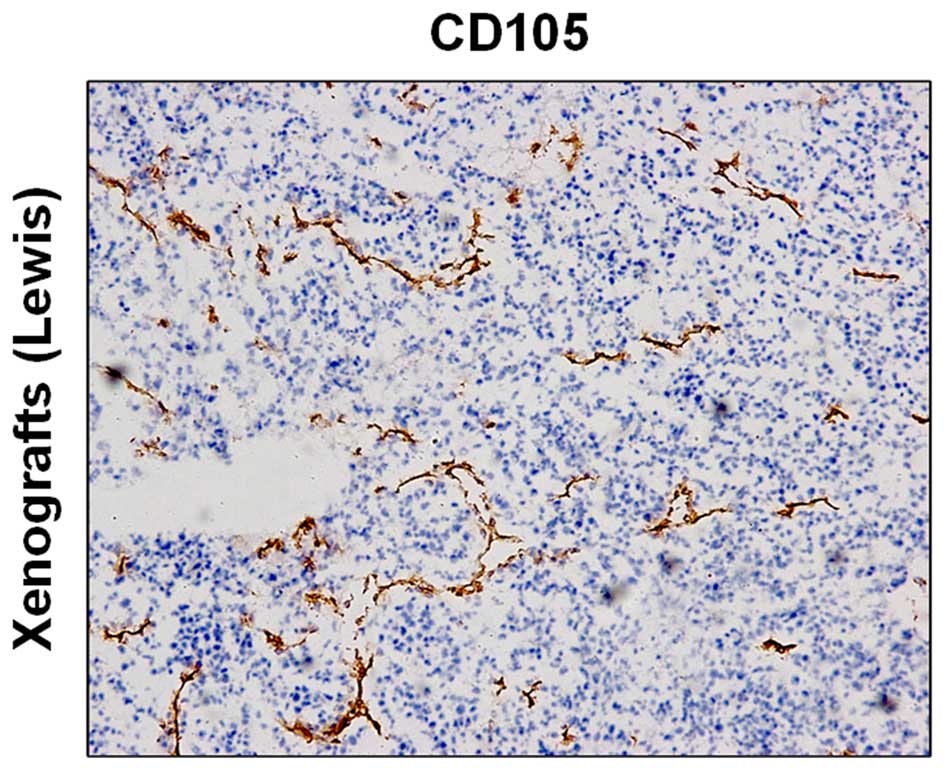

CD105 expression of vascular endothelial

cells in tumor tissues

Immunohistochemistry revealed high expression of

CD105 in the tumor tissue (Fig.

1).

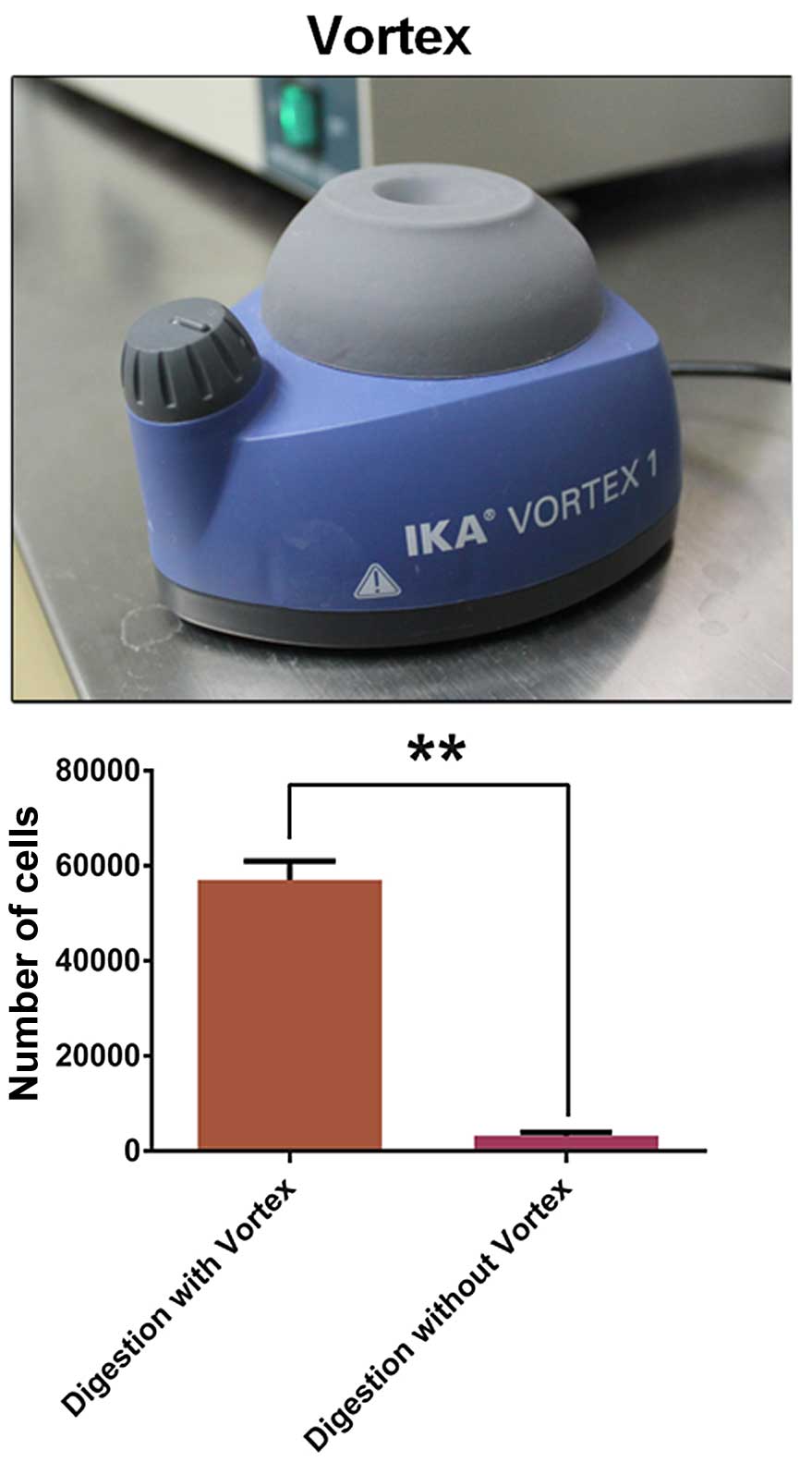

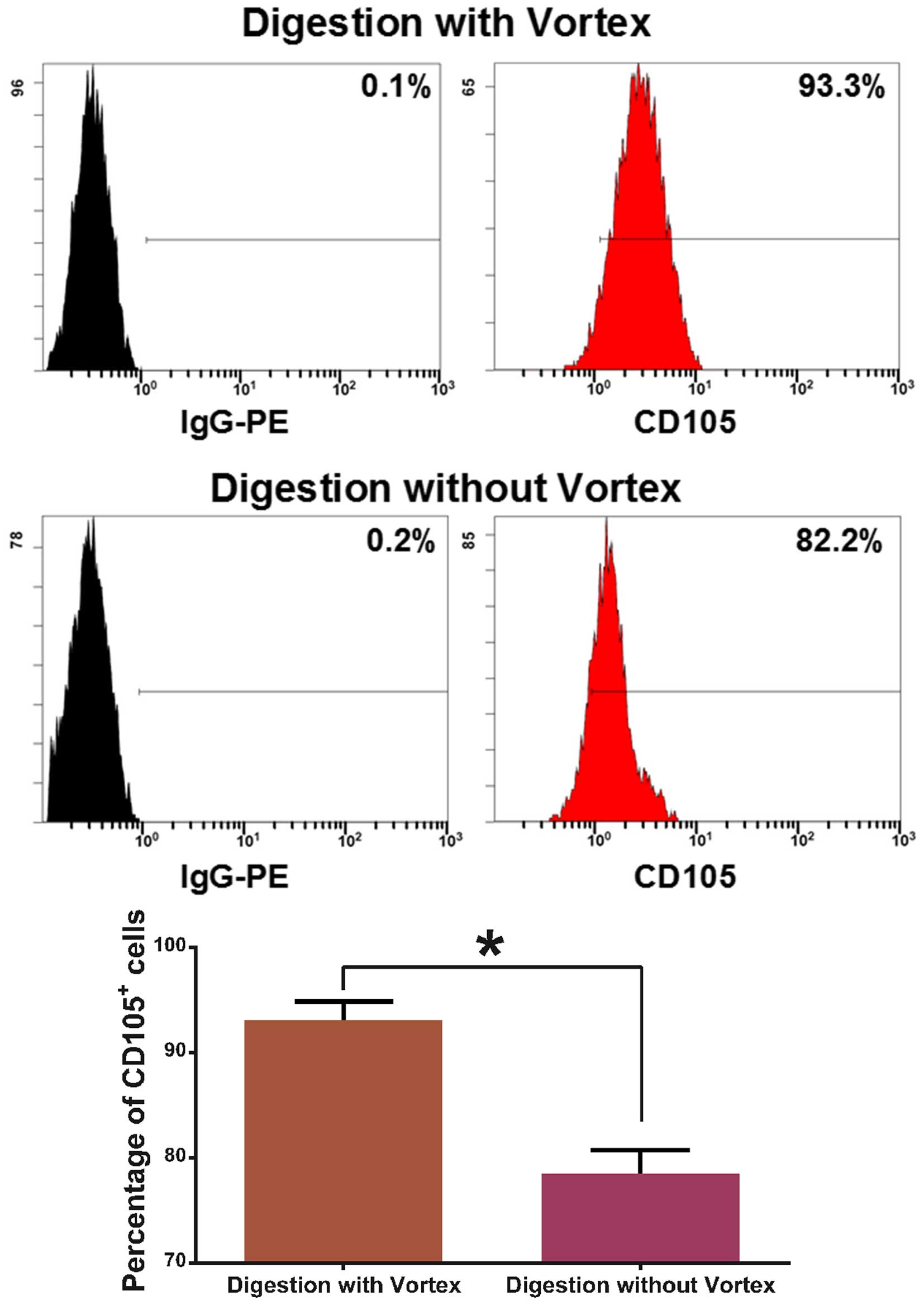

Enrichment and purity of

CD105+ cells

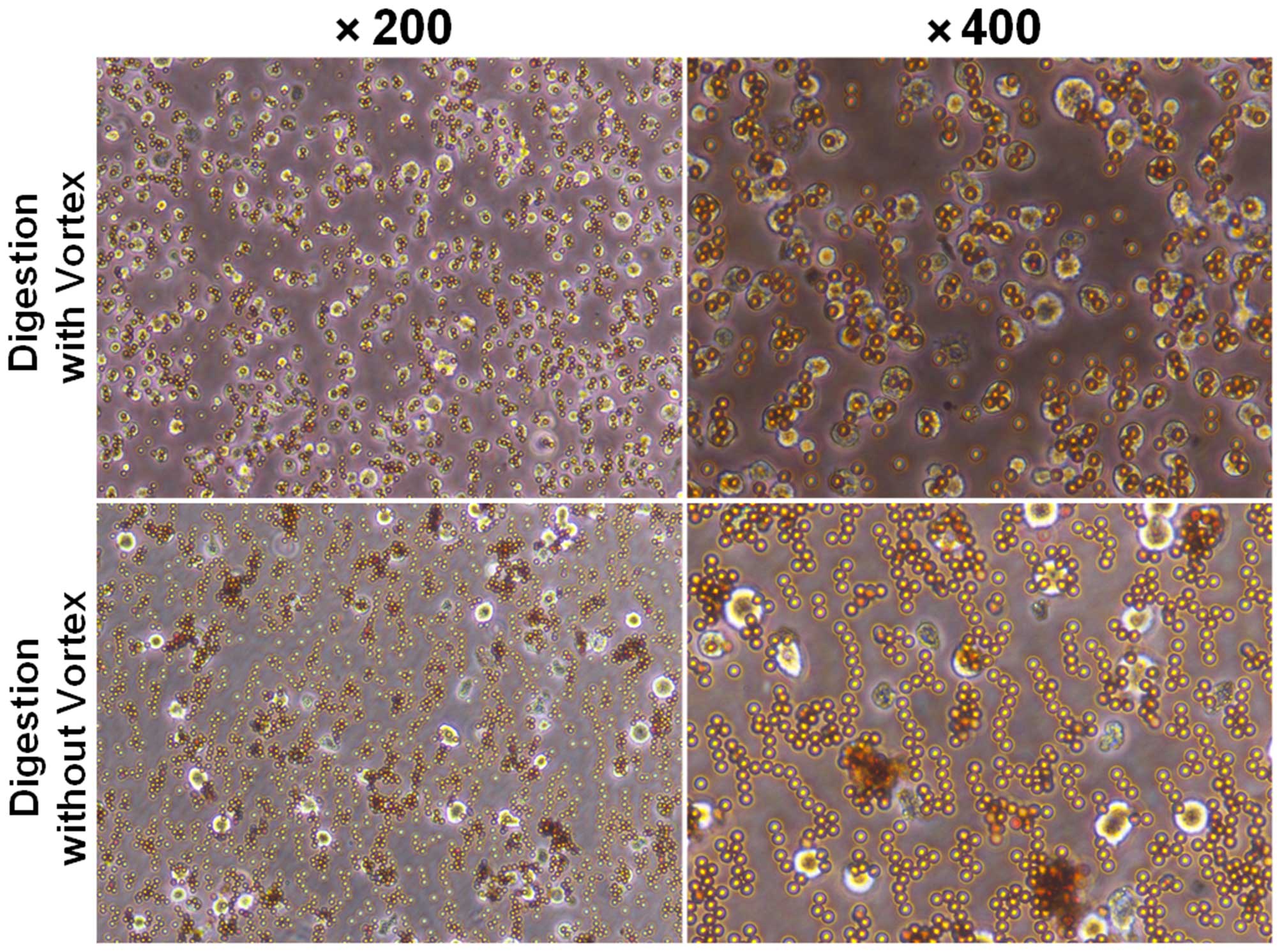

After magnetic separation, the number of

CD105+ cells digested with a vortex

(5.7±0.23×104) was much more than the number without a

vortex (0.32±0.04×104) (Fig.

2). After magnetic cell separation (MACS), we showed that

CD105+ cells combined with microbeads as detected under

a microscope (Fig. 3). The purity

of the CD105+ cells was 93.07±1.7% as established by

digestion with a vortex, while the purity was 78.53±2.2% as

established by digestion without a vortex (Fig. 4).

Detection of CD105+

endothelial cell activity

Dil-ac-LDL uptake assay showed that

CD105+ cells which were digested without a vortex

exhibited red fluorescence, and CD105+ cells which were

digested with a vortex exhibited stronger fluorescence (Fig. 5). Cells which were digested without

a vortex and seeded onto Matrigel formed capillary-like tube

structures within 12 h, while cells which were digested with a

vortex formed more capillary-like tube structures (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In the process of tumor growth, tumor angiogenesis

and apoptosis have emerged as important aspects. Morover,

proangiogenic factors are always dominant during the process of

tumor development. It is well known that during tumor angiogenesis,

endothelial cells undergo cellular and molecular changes that

accompany the phenotypic appearance of angiogenic vessels (11,12).

Angiogenesis is necessary for tumor growth and

metastasis (13,14). CD105 is an important marker in

angiogenesis but is also essential for the proliferation of

endothelial cells and the stimulation of the active phase of

angiogenesis (15–17).

In view of the known heterogeneity of endothelial

cells, it would appear logical to study endothelial cells derived

from tumor tissues when studying the mechanisms of tumor

progression (18–20). Even though methods have been

described for the isolation of endothelial cells, the efficiency

and purity of sorting have not been described.

In the present study, we described a method to

isolate endothelial cells, a rare cell population found in tumor

tissue, through digestion with a vortex. The subsequent isolation

of endothelial cells was achieved using anti-CD105 antibody-coated

microbeads. This purification technique produces isolated cells

with a purity in excess of 93%, and a higher number of

CD105+ cells than that produced by digestion without a

vortex. These cells express surface markers consistent with their

endothelial cell origin, and maintain the ability of capillary

tube-like structure formation and the uptake of acetylated LDL.

This technology has a significantly important role in tumor

angiogenesis research.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by grants from

the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (nos. 81430055,

81172139, 81172138 and 81372452), the International Cooperation

Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (no.

2015DFA31320), the Project for Innovative Research Team in Guangxi

Natural Science Foundation (2015GXNSFFA139001) and the Project of

Science and Technology of Guangxi (nos. 14125008-2-12 and

1599005-2-10).

References

|

1

|

Folkman J: Tumor angiogenesis. Adv Cancer

Res. 43:175–203. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Holzer TR, Fulford AD, Nedderman DM,

Umberger TS, Hozak RR, Joshi A, Melemed SA, Benjamin LE, Plowman

GD, Schade AE, et al: Tumor cell expression of vascular endothelial

growth factor receptor 2 is an adverse prognostic factor in

patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. PLoS One.

8:e802922013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Francescone R, Ngernyuang N, Yan W,

Bentley B and Shao R: Tumor-derived mural-like cells coordinate

with endothelial cells: Role of YKL-40 in mural cell-mediated

angiogenesis. Oncogene. 33:2110–2122. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

4

|

Heuser LS and Miller FN: Differential

macromolecular leakage from the vasculature of tumors. Cancer.

57:461–464. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gerlowski LE and Jain RK: Microvascular

permeability of normal and neoplastic tissues. Microvasc Res.

31:288–305. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hori K, Suzuki M, Tanda S and Saito S: In

vivo analysis of tumor vascularization in the rat. Jpn J Cancer

Res. 81:279–288. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Griffioen AW and Molema G: Angiogenesis:

Potentials for pharmacologic intervention in the treatment of

cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic inflammation.

Pharmacol Rev. 52:237–268. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shi J, Wan Y, Shi S, Zi J, Guan H, Zhang

Y, Zheng Z, Jia Y, Bai X, Cai W, et al: Expression, purification,

and characterization of scar tissue neovasculature endothelial

cell-targeted rhIL10 in Escherichia coli. Appl Biochem Biotechnol.

175:625–634. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Cai G, Satoh T and Hoshi H: Purification

and characterization of an endothelial cell-viability maintaining

factor from fetal bovine serum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1269:13–18.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Behdani M, Zeinali S, Karimipour M,

Khanahmad H, Asadzadeh N, Azadmanesh K, Seyed N, Baniahmad SF and

Anbouhi MH: Expression, purification, and characterization of a

diabody against the most important angiogenesis cell receptor:

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. Adv Biomed Res.

1:342012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

van Beijnum JR, Dings RP, van der Linden

E, Zwaans BM, Ramaekers FC, Mayo KH and Griffioen AW: Gene

expression of tumor angiogenesis dissected: Specific targeting of

colon cancer angiogenic vasculature. Blood. 108:2339–2348. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

St Croix B, Rago C, Velculescu V, Traverso

G, Romans KE, Montgomery E, Lal A, Riggins GJ, Lengauer C,

Vogelstein B, et al: Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium.

Science. 289:1197–1202. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Joshi S, Singh AR, Zulcic M and Durden DL:

A macrophage-dominant PI3K isoform controls hypoxia-induced HIF1α

and HIF2α stability and tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis.

Mol Cancer Res. 12:1520–1531. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ostapoff KT, Awasthi N, Cenik BK, Hinz S,

Dredge K, Schwarz RE and Brekken RA: PG545, an angiogenesis and

heparanase inhibitor, reduces primary tumor growth and metastasis

in experimental pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 12:1190–1201.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nassiri F, Cusimano MD, Scheithauer BW,

Rotondo F, Fazio A, Yousef GM, Syro LV, Kovacs K and Lloyd RV:

Endoglin (CD105): A review of its role in angiogenesis and tumor

diagnosis, progression and therapy. Anticancer Res. 31:2283–2290.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Goumans MJ, Lebrin F and Valdimarsdottir

G: Controlling the angiogenic switch: A balance between two

distinct TGF-b receptor signaling pathways. Trends Cardiovasc Med.

13:301–307. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Slevin M, Krupinski J and Badimon L:

Controlling the angiogenic switch in developing atherosclerotic

plaques: Possible targets for therapeutic intervention. J

Angiogenes Res. 1:42009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Aird WC: Endothelial cell heterogeneity.

Crit Care Med. 31(Suppl 4): S221–S230. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lehmann I, Brylla E, Sittig D,

Spanel-Borowski K and Aust G: Microvascular endothelial cells

differ in their basal and tumour necrosis factor-alpha-regulated

expression of adhesion molecules and cytokines. J Vasc Res.

37:408–416. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Craig LE, Spelman JP, Strandberg JD and

Zink MC: Endothelial cells from diverse tissues exhibit differences

in growth and morphology. Microvasc Res. 55:65–76. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|