Introduction

The American Cancer Society estimated ~23,670 new

cases and 16,050 deaths from brain and nervous system tumors in

adults and children in 2015 (1).

The most common causes of cancer-related deaths in adolescents and

young adults aged 15–39 are malignant brain tumors (2). Gliomas, tumors arising from the

supportive tissue of the brain, represent 27% of all brain tumors

and 80% of all malignant tumors (2). Glioblastomas, which represent 15.1% of

all primary brain tumors and 55.1% of all gliomas, constitute the

highest number of cases of all malignant tumors, with an estimated

12,120 new cases predicted in 2016 (2).

Brain tumors are prone to recur locally or invade

other regions of the central nervous system (CNS). Tumor cell

invasion is dependent upon degradation of the extracellular matrix

(ECM), which, when intact, acts as a barrier to block cancer cell

invasion (3–5). Numerous clinical and experimental

studies have demonstrated that elevated levels of matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs) are associated with the progression of

brain tumors. Elevated levels of several MMPs, such as MMP-1,

MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9, MMP-11, MMP-12, MMP-14, MMP-15, MMP-19, MMP-24

and MMP-25 have been reported in malignant glioma samples from

patients, suggesting that malignant progression is correlated to

MMP expression (6). Jäälinojä et

al found that mean survival in patients with MMP-2-negative

tumors was 36 months in contrast to 7–14 months in those patients

with MMP-2-positive tumors (7).

Smith et al reported that immunohistochemical examination of

urine, cerebrospinal fluid and tissue specimens from patients with

brain tumors, revealed a significant correlation between brain

tumor presence and elevated MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels and that

resection of tumors correlated with decreased levels of MMPs

(8).

MMP activity is regulated by and dependent upon

environmental influences from surrounding stroma cells, ECM

proteins, systemic hormones and other factors. Inflammation has

been reported to drive cancer progression (9–11).

Inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor

necrosis (TNF)-α play significant roles in inflammation driven

tumor growth and progression (12,13).

These cytokines were found to be upregulated following radiation

therapy in glioblastoma patients (14,15).

Ilyin et al noted that IL-1β drives neuroinflammation by

upregulating expression of other pro-inflammatory cytokines

(16). Ryuto et al reported

the induction of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

expression by TNF-α in gliomas, which leads to the increased

angiogenesis observed in these tumors (17).

In the present study, we investigated the effects of

select cytokines, inducers and inhibitors affecting cancer cell

metabolism on the regulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities in the

glioblastoma T-98G cell line.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human glioblastoma T-98G cells were obtained from

the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA).

Antibiotics, penicillin and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained

from Gibco-BRL (Long Island, NY, USA). Twenty-four well tissue

culture plates were obtained from Costar (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Gelatinase zymography was performed on 10% Novex pre-cast SDS

polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 0.1%

gelatin in non-reducing conditions. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor

necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA),

lipopolysaccharide (LPS), doxycycline, epigallocatechin gallate

(EGCG), actinomycin D, cyclohexamide, retinoic acid and

dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The

nutrient mixture (NM), prepared by VitaTech (Hayward, CA, USA), was

composed of the following ingredients in the relative amounts

indicated: vitamin C (as ascorbic acid and as Mg, Ca and palmitate

ascorbate) 700 mg; L-lysine 1,000 mg; L-proline 750 mg; L-arginine

500 mg; N-acetyl cysteine 200 mg; standardized green tea

extract (80% polyphenol) 1,000 mg; selenium 30 µg; copper 2 mg;

manganese 1 mg. All other reagents used were of high quality and

were obtained from Sigma, unless otherwise indicated.

Cell cultures

Glioblastoma cells were grown in DME, supplemented

with 15% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin in

24-well tissue culture plates. The cells were plated at a density

of 1×105 cells/ml and grown to confluency in a

humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2 at 37̊C.

Serum-supplemented media were removed and the cell monolayer was

washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and with the

recommended serum-free media. The cells were then incubated in 0.5

ml of serum-free medium with various cytokines, mitogens, inducers

and inhibitors in triplicates, as indicated: PMA (10, 25, 50 and

100 ng/ml); TNF-α and IL-1β (0.1, 1, 10 and 25 ng/ml); LPS (10, 25,

50 and 100 µg/ml); EGCG (10, 25, 50 and 100 µM) without and with

PMA 100 ng/ml; doxycycline (10, 25, 50 and 100 µM) without and with

PMA 100 ng/ml; NM (10, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 µg/ml) without and

with PMA 100 ng/ml, retinoic acid (50 µM); dexamethasone (50 µM);

actinomycin D and cyclohexamide (2 and 4 µg/ml). The plates were

then returned to the incubator. The conditioned medium from each

treatment was separately collected, pooled and centrifuged at 4̊C

for 10 min at 3,000 rpm to remove cells and cell debris. The clear

supernatant was collected and used for gelatinase zymography, as

described below.

Gelatinase zymography

Gelatinase zymography was utilized due to its high

sensitivity to gelatinolytic enzymatic activity and ability to

detect both pro and active forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Upon

renaturation of the enzyme, the gelatinases digest the gelatin in

the gel and reveal clear bands against an intensely stained

background. Gelatinase zymography was performed using 10% Novex

pre-cast SDS polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 0.1% gelatin

under non-reducing conditions. Culture media (20 µl) were mixed

with sample buffer and loaded for SDS-PAGE with Tris-glycine SDS

buffer, as suggested by the manufacturer (Novex). Samples were not

boiled before electrophoresis. Following electrophoresis, the gels

were washed twice in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room

temperature to remove SDS. The gels were then incubated at 37̊C

overnight in substrate buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl and 10 mM

CaCl2 at pH 8.0 and stained with 0.5% Coomassie Blue

R250 in 50% methanol and 10% glacial acetic acid for 30 min and

destained. Protein standards were concurrently run and approximate

molecular weights were determined by plotting the relative

mobilities of known proteins. Gelatinase zymograms were scanned

using CanoScan 9950F Canon scanner at 300 dpi. The intensity of the

bands was evaluated using the pixel-based densitometer program

Un-Scan-It, version 5.1, 32-bit, by Silk Scientific Corporation

(Orem, UT, USA), at a resolution of 1 Scanner Unit (1/100 of an

inch for an image that was scanned at 100 dpi).

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2010 linear trend analysis was

utilized to determine the linear trend analyses of the densitometry

results.

Results

Effects of inducers and cytokines on

glioblastoma T-98G secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9

Glioblastoma T-98G cells expressed a band

corresponding to MMP-2. Table I

shows the quantitative densitometry results from the effects of

PMA, TNF-α, IL-1β and LPS on MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in the

T-98G cells. Upon gelatinase zymography, T-98G cells demonstrated

strong expression of MMP-2 and induction of MMP-9 with PMA

treatment. PMA treatment showed increased MMP-2 secretion from 0–25

ng/ml and decreased secretion at 50 and 100 ng/ml with no

significant overall effect on expression of MMP-2 (linear trend

R2=0.153). PMA showed increased MMP-9 secretion from 10

to 25 ng/ml followed by decreased secretion at 50 and 100, again

with no significant overall effect on secretion of MMP-9 (linear

trend R2=0.281). See Fig.

1 for PMA results. T-98G cells demonstrated strong expression

of MMP-2 and slight induction of MMP-9 with TNF-α treatment. TNF-α

treatment showed increased MMP-2 secretion from 0–1 ng/ml and

decreased secretion at 10 and 25 ng/ml with no significant overall

effect on expression of MMP-2 (linear trend R2=0.0.066).

TNF-α showed dose-dependent increased MMP-9 secretion (linear trend

R2=0.721). See Fig. 2

for TNF-α results. IL-1β demonstrated a slight dose-dependent

increase in T-98G secretion of MMP-2 (linear trend

R2=0.529), but no induction of MMP-9. See Fig. 3 for IL-1β results. LPS treatment

showed dose-dependent decreased inactive MMP-2 secretion (linear

trend R2=0.473) and increased active MMP-2 secretion

(linear trend R2=0.977) (Fig. 4).

| Table I.Effect of inducers on glioblastoma

T-98G MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion. |

Table I.

Effect of inducers on glioblastoma

T-98G MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion.

|

| MMP-2 (%) | MMP-9 (%) |

|---|

| PMA (ng/ml) |

|

|

| Control | 16.1 | 0 |

| 10 | 16.2 | 1.67 |

| 25 | 22.5 | 7.37 |

| 50 | 15.35 | 6.42 |

| 100 | 11.7 | 2.85 |

| TNF-α (ng/ml) |

|

|

| Control | 12.9 | 0 |

|

0.1 | 20.6 | 0.7 |

|

1 | 23.6 | 1.4 |

| 10 | 22.1 | 1.6 |

| 25 | 15.8 | 1.3 |

| IL-1β (ng/ml) |

|

|

| Control | 15.8 | 0 |

|

0.1 | 13.5 | 0 |

|

1 | 24.4 | 0 |

| 10 | 24.3 | 0 |

| 25 | 22.0 | 0 |

|

| MMP-2 inactive

(%) | MMP-2 active

(%) |

| LPS (µg/ml) |

|

|

| Control | 11.7 | 0 |

| 10 | 17.4 | 3.9 |

| 25 | 15.1 | 9.4 |

| 50 | 9.7 | 10.8 |

| 100 | 5.3 | 16.7 |

Effects of chemical inhibitors on

glioblastoma T-98G cell secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9

Table II shows the

quantitative densitometry results from the effects of chemical

inhibitors doxycycline, actinomycin D, cyclohexamide and

dexamethasone on MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in the glioblastoma

T-98G cell line. Doxycycline inhibited T-98G cell MMP-2 secretion

in a dose-dependent manner with 73% blockage at 100 µM (linear

trend R2=0.899). Following treatment with PMA 100 ng/ml,

doxycycline downregulated the expression of T-98G cell MMP-2 in a

dose-dependent manner, with 73% blockage at 100 µM

(R2=0.898) and total blockage of MMP-9 at 10 µM (linear

trend R2=0.500). See Fig.

5 for doxycycline effects on untreated and PMA-treated T-98G

cells. Actinomycin D had moderate inhibitory effect on MMP-2

secretion (R2=0.725) with ~25% inhibition at 2 and 4 µM,

as shown in Fig. 6. Cyclohexamide

had a potent dose-dependent inhibitory effect on MMP-2 secretion by

T-98G cells with 93% inhibition at 4 µM (linear trend

R2=0.787), as shown in Fig.

7. Dexamethasone had a moderate inhibitory effect on MMP-2,

with inhibition of 23% at 50 µM compared to the control (Fig. 8).

| Table II.Effect of inhibitors on glioblastoma

T-98G MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion. |

Table II.

Effect of inhibitors on glioblastoma

T-98G MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion.

|

| Untreated | PMA 100

ng/ml-treated |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

| MMP-2 (%) | MMP-2 (%) | MMP-9 (%) |

|---|

| Doxycycline

(µM) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 36.9 | 33.0 | 10.6 |

| 10 | 22.2 | 19.8 | 0 |

| 25 | 19.1 | 17.1 | 0 |

| 50 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 0 |

|

100 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 0 |

| EGCG (µM) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 40.0 | 44.9 | 9.2 |

| 10 | 53.5 | 29.3 | 7.0 |

| 25 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 1.2 |

| 50 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

|

100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NM (µg/ml) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 36.9 | 31.4 | 1.9 |

| 10 | 32.8 | 37.1 | 1.2 |

| 50 | 19.3 | 22.0 | 0.1 |

|

100 | 8.2 | 5.0 | 0 |

|

500 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0 |

| 1,000 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Actinomycin D

(µg/ml) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 100.0 | 0 |

| 2 | 75.3 | 0 |

| 4 | 76.1 | 0 |

| Cyclohexamide

(µg/ml) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 100.0 | 0 |

| 2 | 11.1 | 0 |

| 4 | 6.5 | 0 |

| Dexamethasone

(µM) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 100.0 | 0 |

| 50 | 77.4 | 0 |

| Retinoic acid

(µM) |

|

|

|

|

Control | 100.0 | 0 |

| 50 | 45.7 | 0 |

Effects of natural inhibitors on

glioblastoma T-98G secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9

Table II shows the

quantitative densitometry results from the effects of natural

inhibitors EGCG, the NM and retinoic acid on MMP-2 and MMP-9

expression in glioblastoma T-98G cells. EGCG potently downregulated

T-98G expression of MMP-2 in a dose-dependent manner, with total

blockage at 50 µM (linear trend R2=0.712), as shown in

Fig. 9A and C. EGCG showed

dose-dependent inhibition of PMA (100 ng/ml)-induced MMP-9

secretion (linear trend R2=0.866) and of MMP-2 (linear

trend R2=0.877) with total blockage of both at 50 µM, as

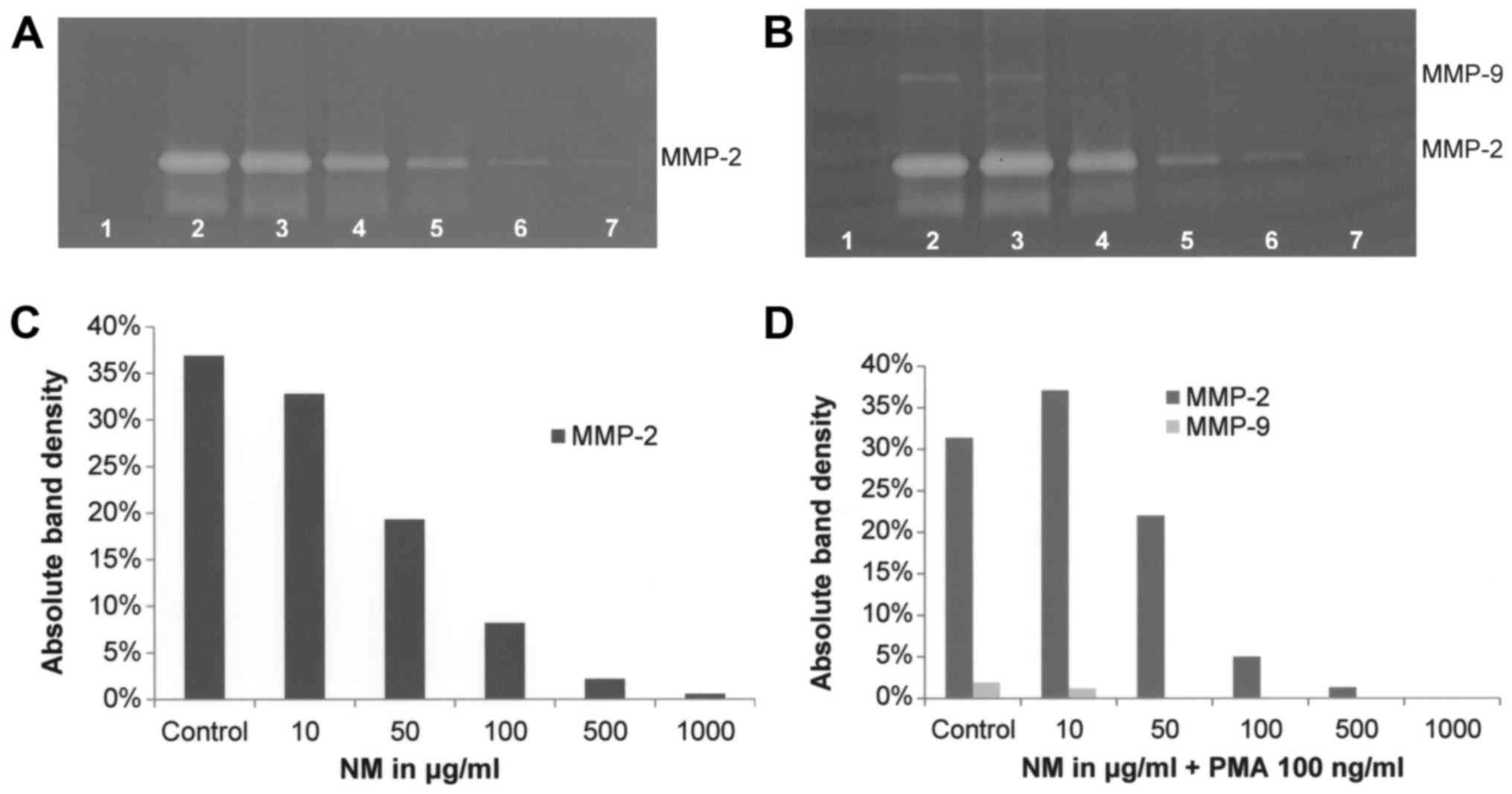

shown in Fig. 9B and D. NM

inhibited secretion of MMP-2 by uninduced T-98G cells in a

dose-dependent manner (linear trend R2=0.8706) with

virtual total block at 1,000 µg/ml (Fig. 10A and C). NM showed dose-dependent

inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in PMA-treated T-98G cells

with total blockage of MMP-2 at 1,000 µg/ml and MMP-9 at 100 µg/ml

(linear trends R2=0.863 and 0.742, respectively), as

shown in Fig. 10B and D. Retinoic

acid inhibited T-98G MMP-2 secretion by 54% at 50 µM (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Elevated MMP levels correlate with glioblastoma

tumor progression, as documented in clinical studies (6–8). Thus,

knowledge of MMP regulation is of importance for developing

therapeutic strategies for glioblastoma. Extracellular factors,

such as the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α have been

implicated in inflammation-driven tumor growth and progression of

glioblastoma (12,13). Esteve et al reported that

production of MMP-9 in glioma cells is tightly regulated by IL-1,

TNFα and TGFβ2 (18).

In the present study, we compared MMP secretion

patterns by inducers, cytokines and mitogens, such as PMA, TNFα,

IL-1β and LPS in glioblastoma T-98G cells. Surprisingly, we found

that MMP-9 was not significantly enhanced by PMA, TNFα and IL-1β in

the present study. LPS increased active MMP-2 secretion and

decreased inactive MMP-2 secretion, but had no effect on MMP-9. In

addition, we investigated the effect of inhibitors, such as

doxycycline, EGCG, NM, dexamethasone, cyclohexamide, retinoic acid

and agents that affect transcription and translation levels, such

as actinomycin D. All inhibitors tested downregulated MMP secretion

by T-98G cells. Doxycycline, a chemical inhibitor, potently

downregulated T-98G secretion of MMP-2 and PMA-induced MMP-9.

Cyclohexamide demonstrated potent inhibitory action on T-98G MMP-2

secretion, while actinomycin D and dexamethasone had moderate

inhibitory effects on MMP-2. Among the natural inhibitors, NM and

its component EGCG potently downregulated T-98G cell secretion of

MMP-2 and MMP-9. Retinoic acid strongly inhibited MMP-2

secretion.

In addition to individual compounds, we tested the

effects of a specific nutrient mixture, NM, which has demonstrated

anticancer efficacy in various in vitro and in vivo

studies by affecting various mechanisms, including secretion of

MMPs (19). Optimal ECM structure

is dependent upon sufficient ascorbic acid, lysine and proline to

support proper collagen synthesis and hydroxylation of collagen

fibers. Lysine also contributes to ECM stability as a natural

inhibitor of plasmin-induced proteolysis (20,21).

Copper and manganese act as co-factors for hydroxylase enzymes and

galactosyl and glucosyl transferases, respectively, to form

collagen (22,23). Green tea extract has been shown to

be potent in modulating cancer cell growth, apoptosis, metastasis

and angiogenesis (23–29), and daily consumption has

demonstrated delayed cancer onset of breast cancer, as well as a

lower recurrence rate and longer remission (30). N-acetyl cysteine and selenium

have been documented to inhibit tumor cell MMP-9 and invasive

activities and migration of endothelial cells through the ECM

(31–33). Ascorbic acid has been documented to

modulate cancer cell and tumor growth as well as to prevent

metastasis (34–39) and low levels of ascorbic acid are

found in cancer patients (40,41).

Low levels of arginine limit NO production, an inducer of apoptosis

(42).

In conclusion, our results showed that inducers,

cytokines and mitogens showed variable effects on T-98G cell

secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9. However, all inhibitors tested

downregulated glioblastoma T-98G cell MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion,

suggesting the clinical use of MMP inhibitors, particularly potent

and non-toxic ones as the nutrient mixture and its component EGCG

in the management of glioblastomas.

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by Dr. Rath Health

Foundation (Santa Clara, CA, USA), a non-profit organization.

References

|

1

|

ACS, . What are the key statistics about

brain and spinal cord tumors? 1 21–2016.Accessed 9/15/16.

http://www.cancer.org/cancer/braincnstumorsinadults/detailedguide/brain-and-spinal-cord-tumors-in-adults-key-statistics

|

|

2

|

ABTA (American Brain Tumor Association), .

Brain Tumor Facts. Last revised 12/2015. 9 15–16.http://www.abta.org/about-us/news/brain-tumor-statistics

|

|

3

|

Yurchenco PD and Schittny JC: Molecular

architecture of basement membranes. FASEB J. 4:1577–1590.

1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Barsky SH, Siegal GP, Jannotta F and

Liotta LA: Loss of basement membrane components by invasive tumors

but not by their benign counterparts. Lab Invest. 49:140–147.

1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liotta LA, Tryggvason K, Garbisa S, Hart

I, Foltz CM and Shafie S: Metastatic potential correlates with

enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen. Nature.

284:67–68. 1980. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Forsyth PA, Laing TD, Gibson AW, Rewcastle

NB, Brasher P, Sutherland G, Johnston RN and Edwards DR: High

levels of gelatinase-B and active gelatinase-A in metastatic

glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 36:21–29. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jäälinojä J, Herva R, Korpela M, Höyhtyä M

and Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T: Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2)

immunoreactive protein is associated with poor grade and survival

in brain neoplasms. J Neurooncol. 46:81–90. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Smith ER, Zurakowski D, Saad A, Scott RM

and Moses MA: Urinary biomarkers predict brain tumor presence and

response to therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 14:2378–2386. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

de Visser KE and Coussens LM: The

inflammatory tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer

development. Contrib Microbiol. 13:118–137. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Coussens LM and Werb Z: Inflammation and

cancer. Nature. 420:860–867. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A and

Balkwill F: Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 454:436–444. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Germano G, Allavena P and Mantovani A:

Cytokines as a key component of cancer-related inflammation.

Cytokine. 43:374–379. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Allavena P, Garlanda C, Borrello MG, Sica

A and Mantovani A: Pathways connecting inflammation and cancer.

Curr Opin Genet Dev. 18:3–10. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gridley DS, Loredo LN, Slater JD,

Archambeau JO, Bedros AA, Andres ML and Slater JM: Pilot evaluation

of cytokine levels in patients undergoing radiotherapy for brain

tumor. Cancer Detect Prev. 22:20–29. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhou W, Jiang Z, Li X, Xu Y and Shao Z:

Cytokines: Shifting the balance between glioma cells and tumor

microenvironment after irradiation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

141:575–589. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ilyin SE, González-Gómez I, Romanovicht A,

Gayle D, Gilles FH and Plata-Salamán CR: Autoregulation of the

interleukin-1 system and cytokine-cytokine interactions in primary

human astrocytoma cells. Brain Res Bull. 51:29–34. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ryuto M, Ono M, Izumi H, Yoshida S, Weich

HA, Kohno K and Kuwano M: Induction of vascular endothelial growth

factor by tumor necrosis factor alpha in human glioma cells.

Possible roles of SP-1. J Biol Chem. 271:28220–28228. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Esteve PO, Tremblay P, Houde M, St-Pierre

Y and Mandeville R: In vitro expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in

glioma cells following exposure to inflammatory mediators. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1403:85–96. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Niedzwiecki A, Roomi MW, Kalinovsky T and

Rath M: Micronutrient synergy - a new tool in effective control of

metastasis and other key mechanisms of cancer. Cancer Metastasis

Rev. 29:529–542. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rath M and Pauling L: Plasmin-induced

proteolysis and the role of apoprotein(a), lysine and synthetic

analogs. Orthomolecular Med. 7:17–23. 1992.

|

|

21

|

Sun Z, Chen YH, Wang P, Zhang J, Gurewich

V, Zhang P and Liu JN: The blockage of the high-affinity lysine

binding sites of plasminogen by EACA significantly inhibits

prourokinase-induced plasminogen activation. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1596:182–192. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Mussini E, Hutton JJ Jr and Udenfriend S:

Collagen proline hydroxylase in wound healing, granuloma formation,

scurvy, and growth. Science. 157:927–929. 1967. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kivirikko KI and Myllylä R: Collagen

glycosyltransferases. Int Rev Connect Tissue Res. 8:23–72. 1979.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Valcic S, Timmermann BN, Alberts DS,

Wächter GA, Krutzsch M, Wymer J and Guillén JM: Inhibitory effect

of six green tea catechins and caffeine on the growth of four

selected human tumor cell lines. Anticancer Drugs. 7:461–468. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mukhtar H and Ahmad N: Tea polyphenols:

Prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am J Clin Nutr. 71

Suppl 6:S1698S–S1704S. 2000.

|

|

26

|

Yang GY, Liao J, Kim K, Yurkow EJ and Yang

CS: Inhibition of growth and induction of apoptosis in human cancer

cell lines by tea polyphenols. Carcinogenesis. 19:611–616. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Taniguchi S, Fujiki H, Kobayashi H, Go H,

Miyado K, Sadano H and Shimokawa R: Effect of (−)-epigallocatechin

gallate, the main constituent of green tea, on lung metastasis with

mouse B16 melanoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 65:51–54. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hara Y: Green Tea: Health Benefits and

Applications. Marcel Dekker; New York, Basel: 2001, http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9780203907993

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gupta S, Hastak K, Afaq F, Ahmad N and

Mukhtar H: Essential role of caspases in

epigallocatechin-3-gallate-mediated inhibition of nuclear factor

kappa B and induction of apoptosis. Oncogene. 23:2507–2522. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fujiki H, Suganuma M, Okabe S, Sueoka E,

Suga K, Imai K, Nakachi K and Kimura S: Mechanistic findings of

green tea as cancer preventive for humans. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med.

220:225–228. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kawakami S, Kageyama Y, Fujii Y, Kihara K

and Oshima H: Inhibitory effect of N-acetylcysteine on invasion and

MMP-9 production of T24 human bladder cancer cells. Anticancer Res.

21:213–219. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Morini M, Cai T, Aluigi Mg, Noonan DM,

Masiello L, De Flora S, D'Agostini F, Albini A and Fassina G: The

role of the thiol N-acetylcysteine in the prevention of tumor

invasion and angiogenesis. Int J Biol Markers. 14:268–271.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yoon SO, Kim MM and Chung AS: Inhibitory

effect of selenite on invasion of HT1080 tumor cells. J Biol Chem.

276:20085–20092. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Cha J, Roomi MW, Ivanov V, Kalinovsky T,

Niedzwiecki A and Rath M: Ascorbate supplementation inhibits growth

and metastasis of B16FO melanoma and 4T1 breast cancer cells in

vitamin C-deficient mice. Int J Oncol. 42:55–64. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Naidu KA, Karl RC, Naidu KA and Coppola D:

Antiproliferative and proapoptotic effect of ascorbyl stearate in

human pancreatic cancer cells: Association with decreased

expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Dig Dis Sci.

48:230–237. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Anthony HM and Schorah CJ: Severe

hypovitaminosis C in lung-cancer patients: The utilization of

vitamin C in surgical repair and lymphocyte-related host

resistance. Br J Cancer. 46:354–367. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Maramag C, Menon M, Balaji KC, Reddy PG

and Laxmanan S: Effect of vitamin C on prostate cancer cells in

vitro: Effect on cell number, viability, and DNA synthesis.

Prostate. 32:188–195. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Koh WS, Lee SJ, Lee H, Park C, Park MH,

Kim WS, Yoon SS, Park K, Hong SI, Chung MH, et al: Differential

effects and transport kinetics of ascorbate derivatives in leukemic

cell lines. Anticancer Res. 18:2487–2493. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen Q, Espey Mg, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB,

Corpe CP, Buettner GR, Shacter E and Levine M: Pharmacologic

ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: Action

as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 102:13604–13609. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Núñez M, artín C, de Apodaca y Ruiz A

Ortiz and Ruiz A: Ascorbic acid in the plasma and blood cells of

women with breast cancer. The effect of the consumption of food

with an elevated content of this vitamin. Nutr Hosp. 10:368–372.

1995.(In Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kurbacher CM, Wagner U, Kolster B,

Andreotti PE, Krebs D and Bruckner HW: Ascorbic acid (vitamin C)

improves the antineoplastic activity of doxorubicin, cisplatin, and

paclitaxel in human breast carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Lett.

103:183–189. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cooke JP and Dzau VJ: Nitric oxide

synthase: Role in the genesis of vascular disease. Annu Rev Med.

48:489–509. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|