Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed

cancer in women. Globally, ~1.3 million new cases are diagnosed

annually (1). China accounted for

12.2% of all newly diagnosed global cases and 9.6% of all breast

cancer-related deaths worlwide in 2008 (2), and since 1990s the incidence in China

has increased more than twice as fast as that of global rates,

particularly in urban areas (3).

Although treatments of breast cancer have significantly been

improved in surgery, radiotherapy and molecular targeted therapy,

chemotherapy is still the major method. Chemotherapy reduced the

risk of disease recurrence and metastasis (4). However, the chemotherapy resistance is

still a major limitation in clinical treatment. Hence, new drugs or

new therapeutic combinations are required to enhance

chemosensitization and therapeutic efficacy (5).

Paclitaxel, one of the most important anticancer

drugs, has been widely used for chemotherapy in ovarian, non-small

cell lung cancer, and head and neck cancer, for almost 40 years,

and it is also the first-line chemotherapy drug used in breast

cancer (6,7). Paclitaxel prompts tubulin

polymerization by binding β-tubulin. By stabilizing the microtubule

polymer and preventing microtubules from disassembly, paclitaxel

arrests the cell cycle in the G2/M phases and induces cell death

(8–10). However, chemotherapy resistance

limits the effect of paclitaxel and influences the prognosis of

patients. Thus, it is particularly important to enhance the

sensitivity of cancer cells to paclitaxel.

Trametes robiniophila Murr. (Huaier), a type

of traditional Chinese medicine, has been widely used in China for

~1,600 years (11). Huaier extract

is the fungus extracted twice with hot water and the effective

ingredient is proteoglycan, containing 41.53% polysaccharides,

12.93% amino acids and 8.72% water (12–14).

However, the anticancer effect of proteoglycan is less effective

than that of the Huaier extract (15). It has been demonstrated that the

main anticancer mechanisms of Huaier are achieved by inhibiting the

growth and proliferation of cancer cells, inducing apoptosis,

decreasing drug resistance in cancer cells, and improving immunity

as well (16,17). In vitro experiments revealed

that Huaier extract inhibited the growth of hepatocarcinoma and

human lung adenocarcinoma cells (18,19).

Huaier extract could inhibit the growth of ERα-positive breast

cancer cells through the ERα/NF-κB pathway (20). A recent study reported that Huaier

extract synergized with tamoxifen to increase autophagy and cell

apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which was more effective

than monotherapy (21).

In 1986, NF-κB was discovered as a nuclear factor

that binds to the enhancer element of the immunoglobulin κ

light-chain of activated B cells (22). Aberrant activation of NF-κB is

frequently found in various solid tumors and hematological

malignancies. NF-κB family members and their regulated genes are

associated with tumor development, tumor cell proliferation,

survival, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis and drug resistance

(23). IκB is the specific

intracellular inhibitor of NF-κB. In most cell types, NF-κB is

present in an inactive form, where it is complexed with IκB in the

cytoplasm (24). A previous study

observed persistent activation of NF-κB in hepatocellular carcinoma

cell lines, and suggested that inhibition of NF-κB signaling

markedly sensitized HCC cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis

(25). In the chemotherapy, drug

resistance is an important problem, as well as the expression

levels of multidrug resistant (MDR) proteins, apoptosis and

anti-apoptosis genes are the main factors of tumor chemosensitivity

(26). Moreover, NF-κB is closely

associated with apoptosis and mediates cell proliferation and

survival. NF-κB can activate a variety of anti-apoptosis genes,

such as Bcl-xL, Bfl/A1 and Bcl-2. Furthermore, the downregulation

of NF-κB and different Bcl-2 family members leads to enhanced

chemosensitization or radio-sensitization of multiple human cancers

(27).

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first

time that Huaier extract combined with paclitaxel induced cell

apoptosis and enhanced paclitaxel drug sensitivity in breast cancer

cells via the NF-κB pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

ER-positive breast cancer cell line MCF-7 and

triple-negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 were obtained

from The Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy Sciences (Shanghai,

China). Huaier extract was kindly provided by Gaitianli Medicine

Co. Ltd. (Jiangsu, Chain). One gram Huaier extract was dissolved in

10 ml of complete RPMI-1640 medium and sterilized with a 0.22-µm

filter to obtain 100 mg/ml stock solution at 4°C. Paclitaxel was

purchased from Yangzijiang Medicine Co. Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). p65,

IκBα and c-Met monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Abcam

(Cambridge, UK). Rabbit anti-human polyclonal β-actin antibody was

purchased from Bioworld Technology Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The

secondary anti-rabbit antibody was purchased from Qiaoyi

Biotechnics Co. Lit (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture

Both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco-BRL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA,

USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biological Industries Israel

Beit-Haemek Ltd., Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel), 100 U/ml penicillin

and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were

routinely cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified

incubator.

Cell viability assay (CCK-8

assay)

Cell viability was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8

(CCK-8) assay. Both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded into

96-well plates at a density of 5×104 cells/well in 100

µl RPMI-1640 medium. After being cultured in 5% CO2, in

a 37°C incubator overnight, the RPMI-1640 medium in each well was

treated with different concentrations of solutions (0, 2, 4, 8, 10

and 16 mg/ml of Huaier extract; 0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 µg/ml

of paclitaxel, or combined therapies) and incubated for 0, 24 or 48

h. Afterwards, 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well for

another 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance at 450 nm was read using a

microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). The inhibitory rate

of cell growth was calculated based on the following equation: Cell

growth inhibition rate = (1 - experimental OD450/control OD450) ×

100%. Based on the statistical analysis of results, 4 and 8 mg/ml

of Huaier extract and 0.01 and 0.1 µg/ml of paclitaxel were used to

explore cell functional studies and mechanisms. For combined

therapies in vitro, the cells were treated with 4 mg/ml

Huaier extract + 0.01 µg/ml paclitaxel (H4 + P0.01) and 8 mg/ml

Huaier extract + 0.1 µg/ml paclitaxel (H8 + P0.1) for 48 h.

Experiments were repeated three times, independently.

Flow cytometric analysis of the cell

cycle and apoptosis

Cell apoptosis was performed using an FITC Annexin V

apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). All

groups of cells were strictly treated under manual processing and

analyzed using a Beckman Coulter Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer

(Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA). The data were analyzed by

EXPO32 ADC analysis software.

Cell cycle analysis was performed using the standard

method with some modifications. Cells were fixed overnight with 75%

ethanol at 4°C. The following day, the fixed cells were washed with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, the cells were suspended

with 200 µl RNase A at 37°C for 10 min, followed by the addition of

250 µl propidium iodide (PI) (100 µg/ml) to stain the DNA of cells

in the dark for 15 min. Finally, the cell cycle was analyzed with a

Beckman Coulter Cytomics FC 500 flow cytometer, and the data was

analyzed using MultiCycle AV for Windows (version 295)

software.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA from treated cells was extracted using

TRIzol and was used to synthesize cDNA using PrimeScript RT reagent

kit (both from Takara, Dalian, China) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Then, real-time PCR was carried out

using PowerUp SYBR-Green Master Mix (Life Technologies, Thermo

Fisher Scientific). The reaction was conducted using the following

parameters: 95°C for 30 sec, 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C

for 30 sec. Internal control and primers for real-time PCR were

obtained from the reference. Real-time PCR primers were synthesized

by SBS Genentech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The specific primers

for P65, IκB, c-Met and the reference gene (β-actin) are listed as

follows: p65 forward, 5′-ACAACCCCTTCCAAGTTCCT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGGTCCCGTGAAATACACCT-3′; IκB forward, 5′-TGAGGACCAGCAGTGTCTTG-3′

and reverse, 5′-CATCGTTGATCACAAGTCGG-3′; c-Met forward,

5′-CATCTCAGAACGGTTCATGCC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGCACAATCAGGCTACTGGG-3′; β-actin forward,

5′-GCTACAGCTTCACCACCACAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGTCTTTACGGATGTCAACGTC-3′. The experiments were repeated at

least three times and the data were analyzed using

2−ΔΔCt.

Western blot analysis

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with

different concentrations of Huaier extract (4 and 8 mg/ml) and/or

paclitaxel (0.01 and 0.1 µg/ml) for 48 h. Τhe cells were lysed and

total protein was separated using 10% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and

transferred (300 mA, 2 h) onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)

membranes. After blotting with 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were

incubated with primary antibodies (anti p65 1:5,000, anti p-p65

1:1,000, anti IκBα 1:1,000, anti c-Met 1:1,000, β-actin 1:5,000) at

4°C overnight. Then, the membranes were washed using Tris-buffered

saline with Tween-20 (TBS-T) buffer and incubated with a secondary

horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled anti-rabbit antibody at room

temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the membranes were washed again

with TBS-T buffer three times (10 min each time). The target

proteins were visualized with a chemiluminescence system (Gene

Company Ltd., Shanghai, China) and normalized to β-actin from the

same membrane.

Xenograft tumorigenicity assay

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (5×106 in 0.1

ml PBS) were subcutaneously injected into four week old female nude

mice. Treatments were started at the second week after injection.

The mice were randomly assigned to control (double-distilled

water), Huaier extract, paclitaxel or combined treatment groups.

The dose of Huaier extract was 250 mg/ml and paclitaxel was 10

mg/kg. The Huaier group was administered 50 mg of Huaier extract by

gavage once every two days, while paclitaxel was administered by

intraperitoneal injection (IP) once a week or both were

administered in the combined treatment group. Tumor growth was

assessed every week and the tumor volume was calculated using the

formula: 0.5 × (length × width2). After six weeks, the

mice were sacrificed and the xenografted tumors were removed for

flow cytometric and western blot analyses.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for

Windows 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student's t-tests and

one-way ANOVA were performed to determine statistical significance.

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)

of three experiments, and P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

Combination of Huaier extract and

paclitaxel exhibits a more effective inhibitory effect on cell

proliferation compared with monotherapies

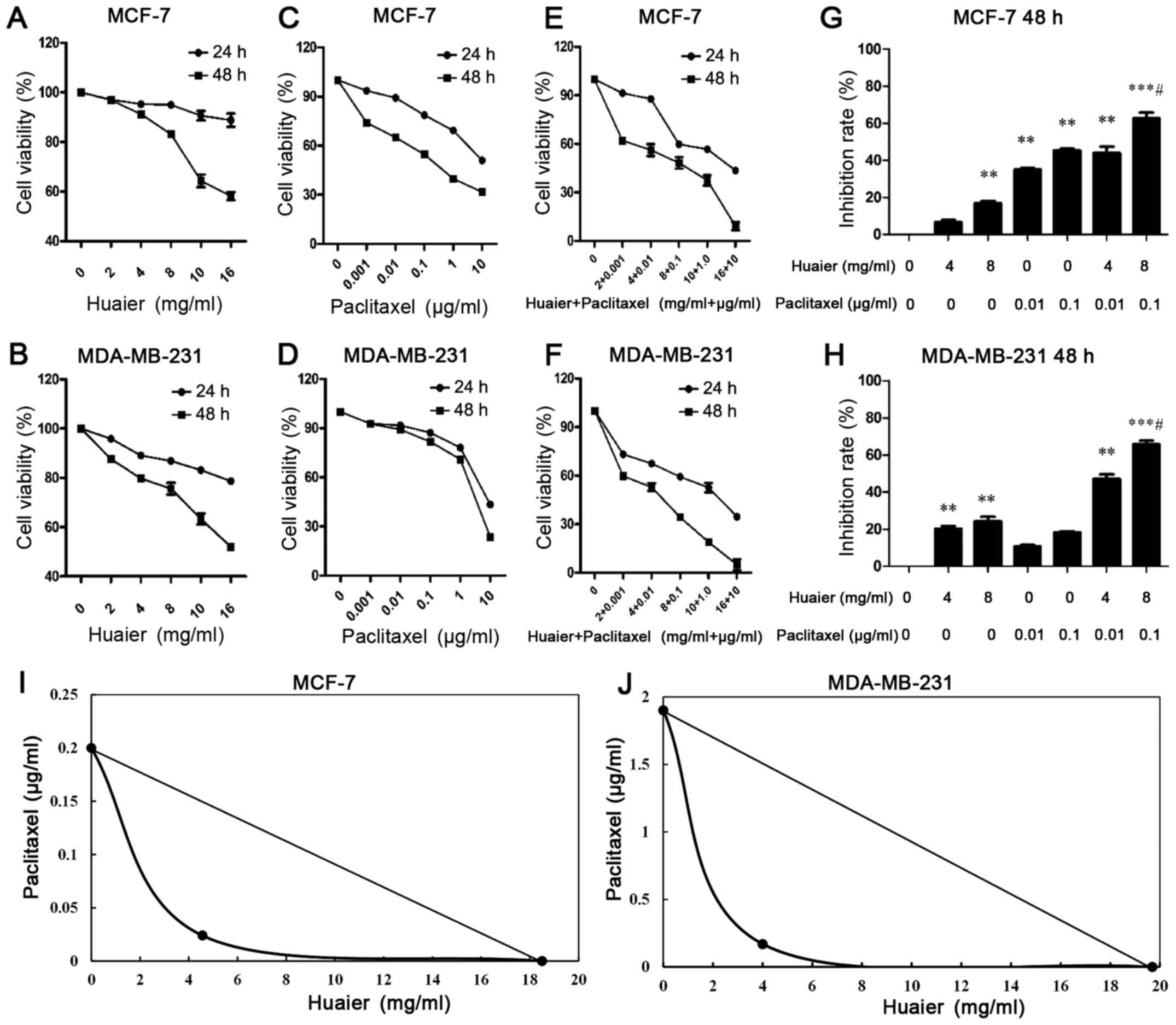

As shown in Fig. 1A and

B, Huaier extract reduced the viability of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. Compared with

the control group, 10 and 16 mg/ml of Huaier extract significantly

decreased cell viability in both cell lines at 24 h (P<0.01). At

48 h, the dosing >4 mg/ml of Huaier extract significantly

reduced the cell viability in both cell lines (P<0.01). We

observed that the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was

significantly inhibited by paclitaxel treatment in a time- and

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C and

D). At 48 h, cell viability was significantly decreased by

paclitaxel treatment as low as 0.01 µg/ml (P<0.05). The combined

therapies sharply decreased the viability of both MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells, and the extent of reduced cell viability by

combined therapies was significantly greater than the monotherapies

of Huaier extract or paclitaxel treatment (Fig. 1E and F). Compared with the 0.1 µg/ml

of paclitaxel treatment alone, the inhibition rate of cell

viability in the combined treatments (H8P0.1) was 1.382±0.161 times

in the MCF-7 cells, and 2.83±0.751 times in the MDA-MB-231 cells

(Fig. 1G and H). In order to

establish a synergistic mode of action between Huaier and

paclitaxel, we performed an isobolometric analysis. The results

revealed that the point was on the left. This suggested that the

combined action was supra-additive in both cell lines (Fig. 1I and J).

Huaier extract combined with

paclitaxel to induce apoptosis in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells

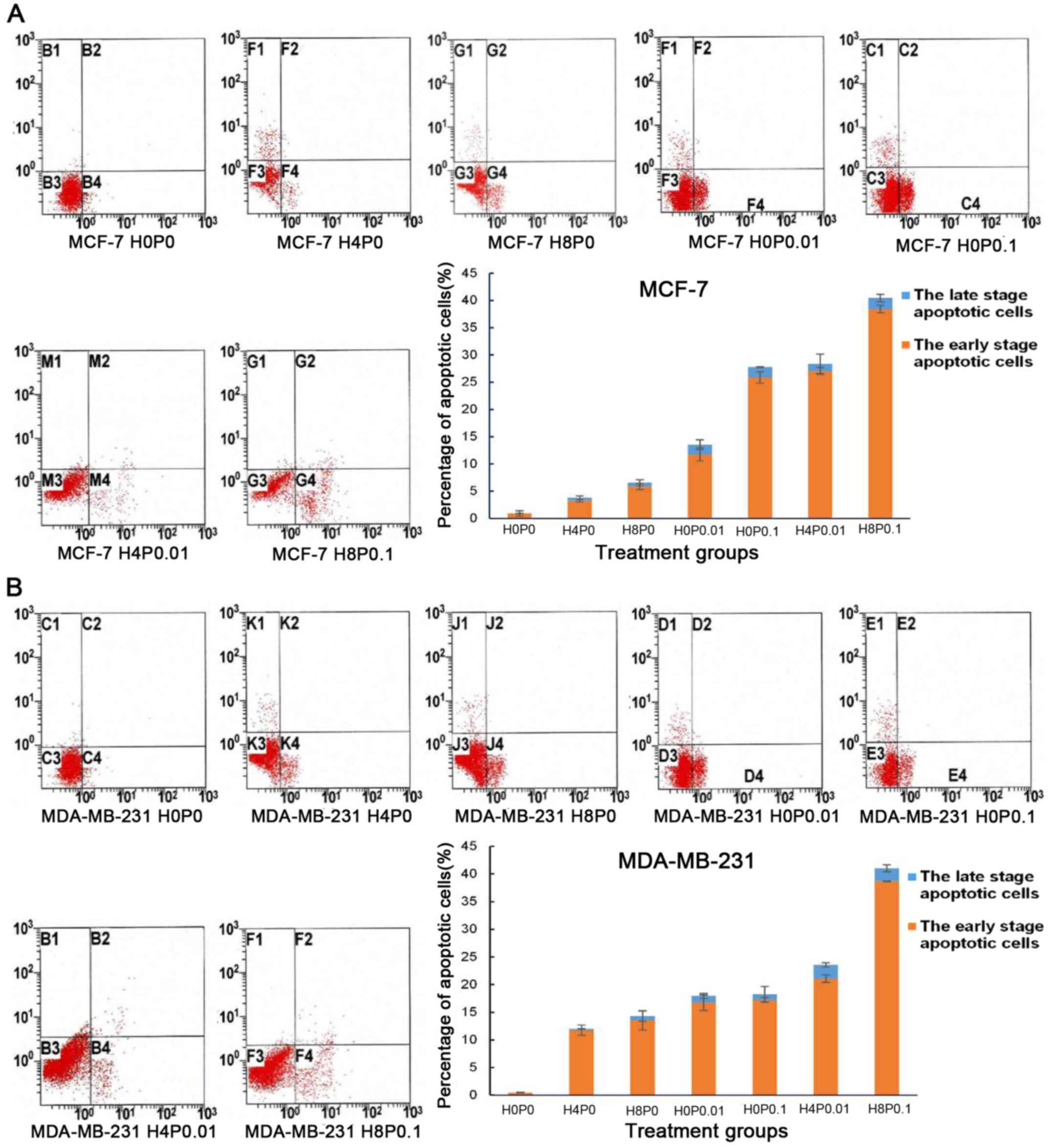

The four quadrants of the apoptosis results: upper

left represents cell debris, upper right represents late-stage

apoptotic, lower left represents living and lower right represents

early-stage apoptotic cells. Compared with the control group,

Huaier extract (H4P0 and H8P0) significantly increased cell

apoptosis in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, and 8 mg/ml of Huaier

extract revealed a more significant effect on cell apoptosis than 4

mg/ml Huaier extract (Fig. 2A and

B; P<0.001). Similar to Huaier extract treatment, paclitaxel

treatment (H0P0.01 and H0P0.1) significantly induced cell apoptosis

in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, and 0.1 µg/ml of paclitaxel

exhibited a more significant effect, particularly in the increase

of early-stage apoptosis (Fig. 2A and

B; P<0.001). The combined treatments of Huaier extract and

paclitaxel revealed a more significant effect on cell apoptosis

than the monotherapies (Fig. 2A and

B). Compared with paclitaxel treatment (H0P0.01 and H0P0.1)

alone, the apoptosis rate in the combined therapy group (H4P0.01

and H8P0.1) increased by 2.139 and 1.431 times, respectively, in

MCF-7 cells (P<0.001). Similarly, in MDA-MB-231 cells, the

apoptosis rate of the combined therapy group (H4P0.01 and H8P0.1)

increased by 1.131 (P<0.05) and 2.245 times (P<0.001),

respectively, compared with paclitaxel treatment alone (H0P0.01 and

H0P0.1).

Huaier extract synergizes with

paclitaxel to induce cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells

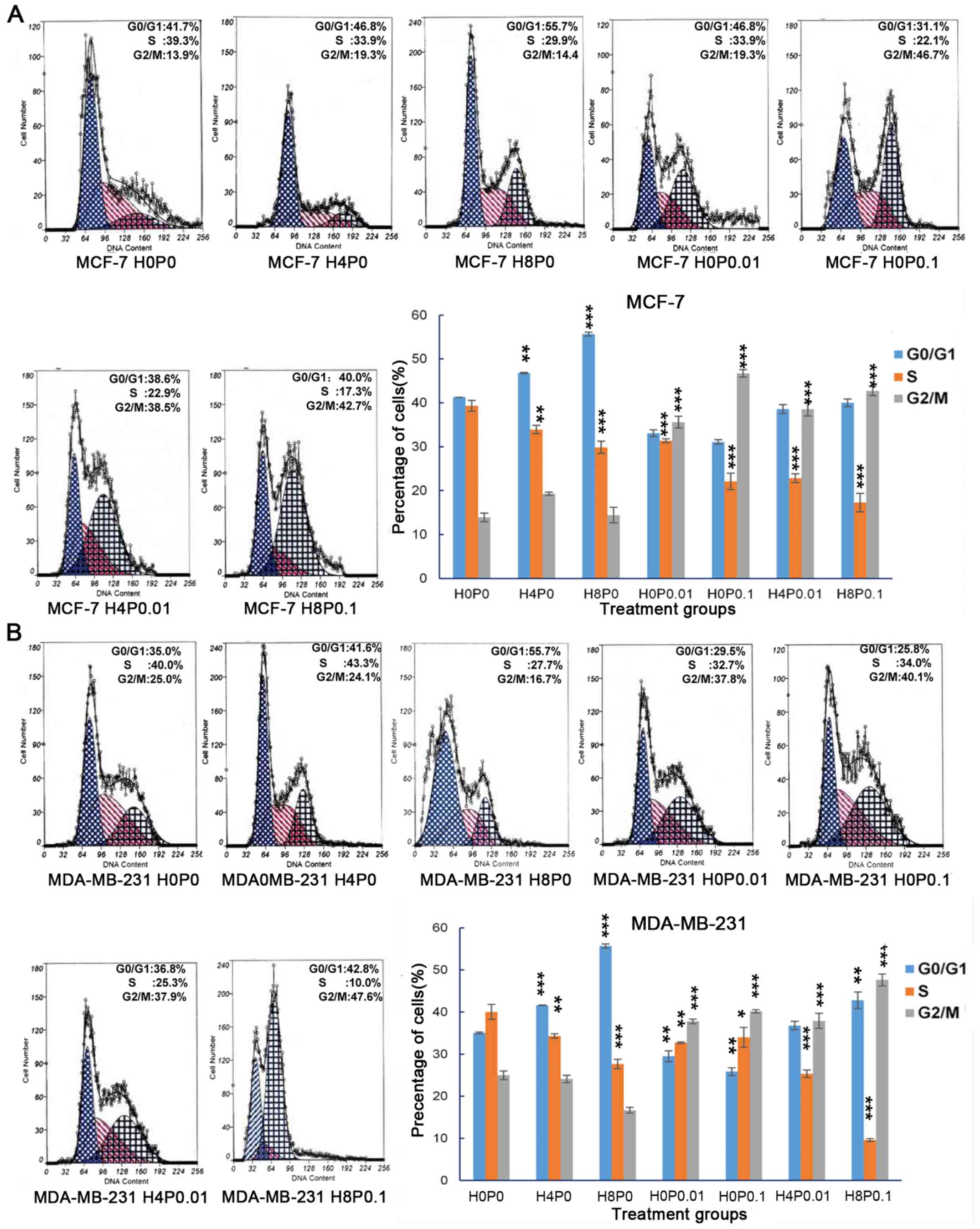

After being exposed to Huaier extract for 48 h, the

percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase significantly increased in

both MCF-7 cells (from 41.268±0.11 to 55.704±0.45%; P<0.001) and

MDA-MB-231 cells (from 35.026±0.23 to 55.659±1.54%; P=0.001), while

the percentage of cells in the S phase was decreased (Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, a higher

concentration of Huaier extract (H8P0) exhibited a stronger effect

on cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase in both cell lines compared

with the lower dose (H4P0). Notably, paclitaxel treatment (H0P0.01

and H0P0.1) also significantly induced cell cycle arrest in both

cell lines, but cell cycle arrest was observed in the G2/M phase

(Fig. 3A and B; P<0.001).

Similar to Huaier extract treatment, paclitaxel treatment reduced

the percentage of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells in the S phase

(P<0.001). Furthermore, we analyzed the cell cycle in MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells after combined therapies and found significant

arrest in both G0/G1 and G2/M phases while the proportion of S

phase was sharply decreased (P<0.001).

Huaier extract and paclitaxel target

p65, IκBα and c-Met in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells

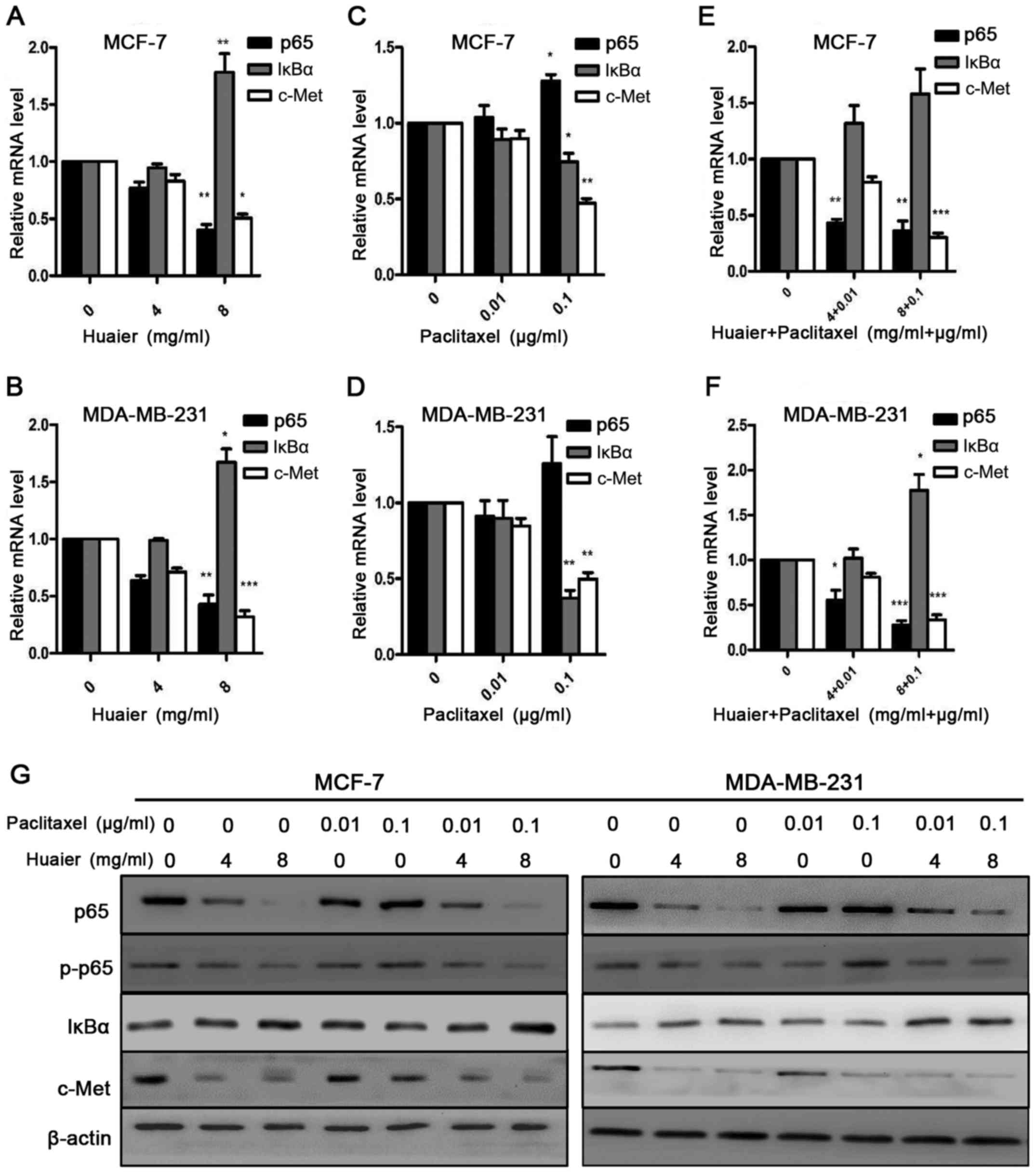

c-Met plays an important role in cell proliferation,

invasion and chemoresistance. The phosphorylation of c-Met

activates multiple downstream signaling pathways, including

Ras/MAPK, PI3K/Akt and NF-κB. Thus, we wanted to detect whether

Huaier and combined treatment mediated c-Met expression. As shown

in Fig. 4A and B and G, after being

treated with Huaier extract (H4P0 and H8P0) for 48 h, the

expression of p65 and c-Met at the mRNA and protein levels was

significantly decreased, while the expression of IκBα was

significantly increased after treatment with H8P0 for 48 h

(P<0.01). Therefore, Huaier extract suppressed the NF-κB/IκBα

pathway. In contrast to the Huaier extract treatment, paclitaxel

treatment (H0P0.01 and H0P0.1) for 48 h significantly increased the

expression of p65 at the mRNA and protein levels in MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells (P<0.05), while the expression of IκBα and

c-Met at the mRNA and protein levels was significantly reduced

(Fig. 4C, D and G). These results

implied that paclitaxel activates the NF-κB pathway. We also

examined the expression of p65, IκBα and c-Met in MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells after combined treatments with Huaier extract and

paclitaxel (Fig. 4E, F and G). The

combined treatments (H4 + P0.01 and H8 + P0.1) significantly

decreased the expression of p65 and c-Met at the mRNA and protein

levels, while the expression of IκBα mRNA and protein was

significantly increased in both cell lines after combined

treatments (P<0.05). These results were similar but more

significant than those of the Huaier extract treatment alone.

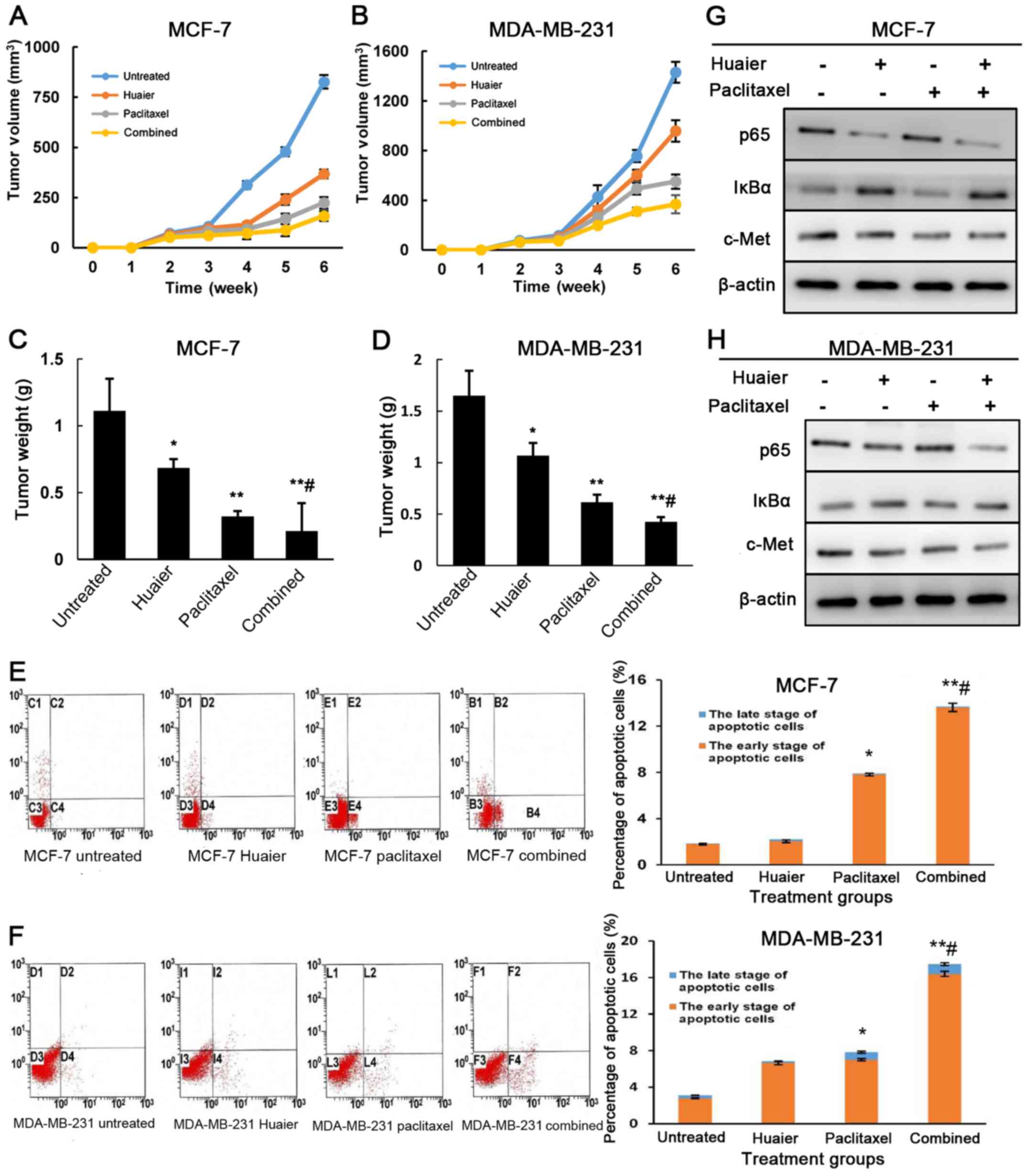

Combined Huaier extract and paclitaxel

treatments inhibit tumor growth in a xenograft model

To ascertain the inhibitory effect of Huaier extract

and paclitaxel on breast cancer cells, we examined the antitumor

effect of Huaier extract, paclitaxel and combined treatment in nude

mice. Compared with the control group (825.8±33.7 mm3),

the tumor volume in the Huaier (367.3±22.1 mm3;

P<0.05), paclitaxel (223.9±28.2 mm3; P<0.01) and

combined treatment group (158.1±25.2 mm3; P<0.01) was

significantly smaller in MCF-7 xenografted tumors (Fig. 5A). However, there was no significant

difference in the volume between the combined group and paclitaxel

group (P=0.144). Similar results were observed in the MDA-MB-231

xenografted tumors (Fig. 5B), but

the tumor volume in the combined group was smaller than that in the

paclitaxel group (P<0.05). After the mice were sacrificed, we

assessed the tumor weight (Fig. 5C and

D). The tumor weight in each group was consistent with that of

tumor volume in both cell lines (P<0.05). Moreover, compared

with the paclitaxel group, the tumor weight in the combined group

was lighter in both xenografted tumors (P<0.05). To examine the

antitumor mechanisms of the Huaier extract, paclitaxel and the

combined treatment in vivo, we analyzed the apoptosis and

the expression of p65 and IκBα in xenografted tumors. As shown in

Fig. 5E and F, the combined

treatments caused the most significant apoptosis compared to the

control and monotherapy groups. Furthermore, combined treatment

significantly decreased the expression of p65 and c-Met, but

increased IκBα expression in xenografted tumors compared with those

from monotherapies (Fig. 5G and

H).

Discussion

Breast cancer, as a highly heterogeneous tumor, is

significantly different in pathological type, molecular

classification and prognosis. Estrogen receptor-positive breast

cancer accounts for ~70% of breast cancer and triple-negative

breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for ~10–20% (28). Although ER-positive breast cancer

patients can benefit from endocrine therapy, chemotherapy is still

an important systemic therapy after surgery for preventing

recurrent and metastasis. Chemotherapy is the only treatment for

TNBC presently, since TNBC is invasive, recurs and metastasizes

easily and thus TNBC cannot benefit from endocrine and target

therapy.

Recently, traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) have

been considered as anticancer drugs for their ability to kill

cancer cells, and reduce the side-effects of chemotherapy. Huaier

extract has been found to not only have an antitumor effect, but

also enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs

and improve immunity and long-term prognosis in cancer patients

(29,30). Bao et al (18) found that the Huaier extract

inhibited the proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma

Hep-G2 cells and induced cell apoptosis in a

concentration-dependent manner. In the present study, after

treating MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells with Huaier extract for 24 and

48 h, we found that Huaier extract inhibited cell proliferation,

reduced cell viability and promoted cell apoptosis in a time- and

dose-dependent manner, results which were consistent with a study

from Zhang et al (14). We

also found that Huaier extract could induce cell cycle arrest in

the G0/G1 phase, which was in line with a study by Qi et al

(21). A previous study

demonstrated that paclitaxel treatment caused cell cycle arrest in

the G2/M phase, inhibited mitotic progression and induced apoptotic

cell death (31). In the present

study, we found that combined therapies of Huaier extract and

paclitaxel treatments in breast cancer cells induced cell cycle

arrest in the G0/G1 and G2/M phases, but reduced the percentage of

cells in the S phase. These results revealed that both Huaier

extract and paclitaxel treatments inhibited cell proliferation

activity and induced cell apoptosis in breast cancer cells, and the

combined therapies achieved the most effective efficacy.

Our research also studied the relationship between

the anticancer effect of paclitaxel and the NF-κB pathway. Current

studies have suggested that paclitaxel functions by binding to

tubulin, promoting the formation of stable microtubules and

inhibiting microtubule depolymerization. Thus, paclitaxel

interferes with the normal function of mitotic spindle formation,

arrests the cell cycle in the G2/M phase and induces cell death in

cancer (32). Our results revealed

that paclitaxel reduced IκBα expression, but increased p65

expression. As the inhibitory protein of NF-κB, the reduction of

IκBα expression was associated with NF-κB activation. Similar

results were also observed in a study in which paclitaxel induced

the degradation of the IκBα protein, which in turn activated NF-κB

and induced cell apoptosis (33).

Bava et al (34) reported

that paclitaxel treatment after 30 min may lead to the

translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus of HeLa cells. NF-κB

activation plays an important role in the resistance to cytotoxic

agents (such as doxorubicin), microtubule disrupting agents (such

as paclitaxel) and 5-fluorouracil (27,31).

Our data indicated that paclitaxel treatment for 48 h may induce

drug resistance via NF-κB activation.

In a previous study, the combination of Huaier

extract with chemotherapy drugs promoted tumor cell apoptosis and

improved sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy drugs (15), but the mechanism is still not clear.

Zhang et al (35) reported

that Huaier increased the sensitivity of MCF-7/A breast cancer

cells to adriamycin (ADM) which was related to the decrease in the

expression of drug resistant gene MDR-1. Another study revealed

that Huaier extract synergized with tamoxifen (TAM) to increase

apoptosis and G0/G1 arrest in ER-positive breast cancer cells

(21). However, in the actively

proliferative cancer cells, the proportion of G0/G1 and S phase

cells was much higher than the proportion of G2/M phase cells.

Paclitaxel mainly induced cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase,

while Huaier extract caused cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase.

Therefore, paclitaxel and Huaier complemented each other and the

anticancer effect produced from their combination treatment was

significantly improved. Moreover, the inhibition of NF-κB (p65) was

more effective after combined therapies. A previous study suggested

that the inhibition of NF-κB can improve tumor cell sensitivity to

chemotherapy drugs (36). Our

results revealed that compared with monotherapies, the combined

therapies increased cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 and G2/M phases,

more significantly promoted cell apoptosis, inhibited NF-κB and

enhanced antitumor efficacy.

The encoding product of proto-oncogene c-met

is the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (also known as c-Met),

which is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase. c-Met plays an important

role in cell proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis (37). In breast cancer tissue particularly

TNBC, c-Met was abnormally expressed (38). The phosphorylation of c-Met

activated multiple downstream signaling pathways, including

Ras/MAPK, PI3K/Akt and NF-κB (39).

Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway increased cell survival and

inhibited apoptosis. Akt can regulate the NF-κB pathway. In a

future study we would like to further investigate the relationship

between drug resistance reversion by Huaier and c-Met/Akt/NF-κB. In

the present study, both the Huaier extract and paclitaxel inhibited

the expression of c-Met, and their combination in a high-dose group

revealed the most inhibitory effect on c-Met expression. These

results revealed that combined treatments may enhance the antitumor

effect of paclitaxel therapy in breast cancer cells.

Our results demonstrated that Huaier-induced

inhibition of the NF-κB pathway resulted in the suppression of cell

proliferation and the promotion of apoptosis. Paclitaxel-induced

NF-κB activation was associated with chemoresistance and a

decreased antitumor effect. Huaier reversed the effect of

paclitaxel on the activation of NF-κB, and thus, suppressed cell

proliferation and increased the antitumor effect. The NF-κB pathway

may play an important role in the combined treatment. In future,

further research into the molecular mechanisms and the proteins

involved in the cell cycle and proliferation as well as

resistance-associated genes regulated by NF-κB is warranted in

order to obtain more valuable insights.

In summary, Huaier extract synergized with

paclitaxel to suppress proliferation and increase apoptosis in

ER-positive breast cancer cells and TNBC. The mechanisms were

involved in inducing cell cycle arrest and cell apoptosis and

inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. Moreover, the combined treatments

of Hauier extract and paclitaxel were more effective on antitumor

activity than the monotherapies, which may increase the anticancer

effect of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel therapy.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Hebei

Province Natural Science Foundation (H2012206169).

References

|

1

|

Panieri E: Breast cancer screening in

developing countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

26:283–290. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D,

Mathers C and Parkin DM: Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in

2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 127:2893–2917. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fan L, Zheng Y, Yu KD, Liu GY, Wu J, Lu

JS, Shen KW, Shen ZZ and Shao ZM: Breast cancer in a transitional

society over 18 years: Trends and present status in Shanghai,

China. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 117:409–416. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kim YM, Tsoyi K, Jang HJ, Park EJ, Park

SW, Kim HJ, Hwa JS and Chang KC: CKD712, a synthetic isoquinoline

alkaloid, enhances the anti-cancer effects of paclitaxel in

MDA-MB-231 cells through regulation of PTEN. Life Sci. 112:49–58.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sonnenblick A, Eleyan F, Peretz T, Ospovat

I, Merimsky O, Sella T, Peylan-Ramu N and Katz D: Gemcitabine in

combination with paclitaxel for advanced soft-tissue sarcomas. Mol

Clin Oncol. 3:829–832. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wall ME, Wani MC and Taylor H: Plant

antitumor agents, 27. Isolation, structure, and structure activity

relationships of alkaloids from Fagara macrophylla. J Nat Prod.

50:1095–1099. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Quispe-Soto ET and Calaf GM: Effect of

curcumin and paclitaxel on breast carcinogenesis. Int J Oncol.

49:2569–2577. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wen G, Qu XX, Wang D, Chen XX, Tian XC,

Gao F and Zhou XL: Recent advances in design, synthesis and

bioactivity of paclitaxel-mimics. Fitoterapia. 110:26–37. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bharadwaj R and Yu H: The spindle

checkpoint, aneuploidy, and cancer. Oncogene. 23:2016–2027. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Brito DA, Yang Z and Rieder CL:

Microtubules do not promote mitotic slippage when the spindle

assembly checkpoint cannot be satisfied. J Cell Biol. 182:623–629.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li LX, Ye SL, Wang YH and Tang ZZ:

Progress on experimental research and clinical application of

Trametes robiniophila. Bull Chin Cancer. 16:110–113.

2007.

|

|

12

|

Guo YW, Cheng PW, Chen YJ, et al: Studies

on the constituents of polysaccharide from the hyphae of

Trametes robiniophila (II) - identification of

polysaccharide from the hyphae of Trametes robiniophila and

determination of its molar ratio. J Chin Pharm U. 23:155–157.

1992.

|

|

13

|

Guo Y, Cheng P and Chen Y: Isolation and

analysis of the polysaccharide of Huaier mycelium. Chin J Biochem

Pharm. 63:56–59. 1993.

|

|

14

|

Zhang N, Kong X, Yan S, Yuan C and Yang Q:

Huaier aqueous extract inhibits proliferation of breast cancer

cells by inducing apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 101:2375–2383. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Huo Q and Yang QF: Role of Huaier extract

as promising anticancer drug. Adaptive Med. 4:2076–944X. 2012.

|

|

16

|

Zhang T, Wang K, Zhang J, Wang X, Chen Z,

Ni C, Qiu F and Huang J: Huaier aqueous extract inhibits colorectal

cancer stem cell growth partially via downregulation of the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Oncol Lett. 5:1171–1176. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zheng J, Li C, Wu X, Liu M, Sun X, Yang Y,

Hao M, Sheng S, Sun Y, Zhang H, et al: Astrocyte elevated gene-1

(AEG-1) shRNA sensitizes Huaier polysaccharide (HP)-induced

anti-metastatic potency via inactivating downstream P13K/Akt

pathway as well as augmenting cell-mediated immune response. Tumour

Biol. 35:4219–4224. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bao H, Liu P, Jiang K, Zhang X, Xie L,

Wang Z and Gong P: Huaier polysaccharide induces apoptosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells through p38 MAPK. Oncol Lett.

12:1058–1066. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xie HX, Xu ZY, Tang JN, Du YA, Huang L, Yu

PF and Cheng XD: Effect of Huaier on the proliferation and

apoptosis of human gastric cancer cells through modulation of the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 10:1212–1218. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang X, Zhang N, Huo Q, Sun M, Lv S and

Yang Q: Huaier aqueous extract suppresses human breast cancer cell

proliferation through inhibition of estrogen receptor α signaling.

Int J Oncol. 43:321–328. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Qi W, Sun M, Kong X, Li Y, Wang X, Lv S,

Ding X, Gao S, Cun J, Cai C, et al: Huaier extract synergizes with

tamoxifen to induce autophagy and apoptosis in ER-positive breast

cancer cells. Oncotarget. 7:26003–26015. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sen R and Baltimore D: Multiple nuclear

factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell.

46:705–716. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li F, Zhang J, Arfuso F, Chinnathambi A,

Zayed ME, Alharbi SA, Kumar AP, Ahn KS and Sethi G: NF-κB in cancer

therapy. Arch Toxicol. 89:711–731. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang W, Nag SA and Zhang R: Targeting the

NFκB signaling pathways for breast cancer prevention and therapy.

Curr Med Chem. 22:264–289. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhao N, Wang R, Zhou L, Zhu Y, Gong J and

Zhuang SM: MicroRNA-26b suppresses the NF-κB signaling and enhances

the chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting

TAK1 and TAB3. Mol Cancer. 13:352014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pommier Y, Sordet O, Antony S, Hayward RL

and Kohn KW: Apoptosis defects and chemotherapy resistance:

Molecular interaction maps and networks. Oncogene. 23:2934–2949.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li F and Sethi G: Targeting transcription

factor NF-kappaB to overcome chemoresistance and radioresistance in

cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1805:167–180. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, St Louis

J, Finkelstein DM, Yu KD, Chen WQ, Shao ZM and Goss PE: Breast

cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 15:e279–e289. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ji D and Mai D: Effect of Huaier Granule

on immunity and quality of life in patient with gastric cancer

undergoing postoperative concurrent radiochemotherapy. China

Cancer. 19:73–76. 2010.

|

|

30

|

Song X, Li Y, Zhang H and Yang Q: The

anticancer effect of Huaier (Review). Oncol Rep. 34:12–21. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jeong YJ, Kang JS, Lee SI, So DM, Yun J,

Baek JY, Kim SK, Lee K and Park SK: Breast cancer cells evade

paclitaxel-induced cell death by developing resistance to

dasatinib. Oncol Lett. 12:2153–2158. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

McGrogan BT, Gilmartin B, Carney DN and

McCann A: Taxanes, microtubules and chemoresistant breast cancer.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1785:96–132. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Huang Y, Johnson K, Norris J and Fan W:

NF-kB/IkB signaling pathways may contribute to the mediation of

paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in solid tumor cells. Cancer Res.

60:4426–4432. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bava SV, Sreekanth CN, Thulasidasan AK,

Anto NP, Cheriyan VT, Puliyappadamba VT, Menon SG, Ravichandran SD

and Anto RJ: Akt is upstream and MAPKs are downstream of NF-κB in

paclitaxel-induced survival signaling events, which are

down-regulated by curcumin contributing to their synergism. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 43:331–341. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang YB, Zhang GQ, Wang JS and Zhang QF:

Function and clinical application of Huaier plaster in

comprehensive therapy of breast cancer. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehabil.

11:62004.

|

|

36

|

Uetsuka H, Haisa M, Kimura M, Gunduz M,

Kaneda Y, Ohkawa T, Takaoka M, Murata T, Nobuhisa T, Yamatsuji T,

et al: Inhibition of inducible NF-kappaB activity reduces

chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil in human stomach cancer cell

line. Exp Cell Res. 289:27–35. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Maroun CR and Rowlands T: The Met receptor

tyrosine kinase: A key player in oncogenesis and drug resistance.

Pharmacol Ther. 142:316–338. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Raghav KP, Wang W, Liu S, Chavez-MacGregor

M, Meng X, Hortobagyi GN, Mills GB, Meric-Bernstam F, Blumenschein

GR Jr and Gonzalez-Angulo AM: cMET and phospho-cMET protein levels

in breast cancers and survival outcomes. Clin Cancer Res.

18:2269–2277. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C and

Vande Woude G: Targeting MET in cancer: Rationale and progress. Nat

Rev Cancer. 12:89–103. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|