Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most severe malignant

tumors and it also has high rates of morbidity especially in many

developing countries (1). China's

National Cancer Center earlier published data showed that the

incidence and mortality rate of cervical cancer is

10.4/105 and 2.59/105 (2). Contemporary management of cervical

cancer involves chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy (3). As recommended by the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), Platinum-based chemotherapy is

often used in cervical cancer management (4). However, common platinum-based drugs,

for example, cisplatin, often induce resistance. Thus there is an

urgent need of novel drugs for cervical cancer management (5).

The heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP)

family consists of approximately 20 hnRNA-binding proteins and most

of them are related to key biogenesis of messenger RNA (mRNA)

(6). The hnRNP A2/B1 complex are

important members of hnRNP family and are made up of the proper

proportion of protein A and protein B, it has been proved that

hnRNPs regulate transportation and splicing of mRNA in cells

(7,8). Several studies have demonstrated that

hnRNP A2/B1 was highly expressed in gastric adenocarcinoma,

pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma. Overexpression of hnRNP A2/B1

in non-small cell lung cancer increased cell proliferation, while

downregulation of hnRNP A2/B1 enhanced apoptosis of breast cancer

cells. Importantly, hnRNP A2/B1 has been used as biomarker and

prognostic indicator in non-small cell lung cancer (9–13).

However, the role of hnRNP A2/B1 in cervical cancer has not been

fully studied.

Phophatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase-B

(PI3K/AKT) signaling pathway and its downstream targets play

important roles in tumorigenesis. For example, PI3K/AKT pathway

trigger tumor cell death through binding to Bad/Bcl-2 complex and

inactive caspase-8/9 (14,15). Moreover, the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway is involved in cell proliferation by activating cyclin

dependent kinase (CDK), upregulating cyclins and downregulating

p21/Waf1/Cip1 and p27/Kip2 (16). A

study based on the Cancer Genome Atlas revealed that the expression

of the subunits of PI3K/AKT varies in cervical cancer, ovarian

cancer and uterine epithelial tumor (17). However the relationship between

hnRNP A2/B1 and PI3K/AKT in cervical cancer has not been fully

clarified.

From previous research, we found that hnRNP A2/B1

was inhibited in CaSki cells after treatment with lobaplatin

(18). However the relationship

between hnRNP A2/B1 and PI3K/AKT in cervical cancer is not clear

and the underlying mechanism remains unknown. Thus, in this study,

we explored the role of hnRNP A2/B1 in proliferation, apoptosis as

well as relationship between hnRNP A2/B1 and PI3K/AKT pathway in

cervical cancer both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human cervical cancer cells HeLa and CaSki were

purchased from the cell bank of the Type Culture Collection of

Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured

in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and 1%

L-glutamine (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) in a 5% CO2

incubator at 37°C. The medium was replaced every 2–3 days, and

subsequent studies were performed when cells in exponential growth

phase.

hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA design and cell

transfection

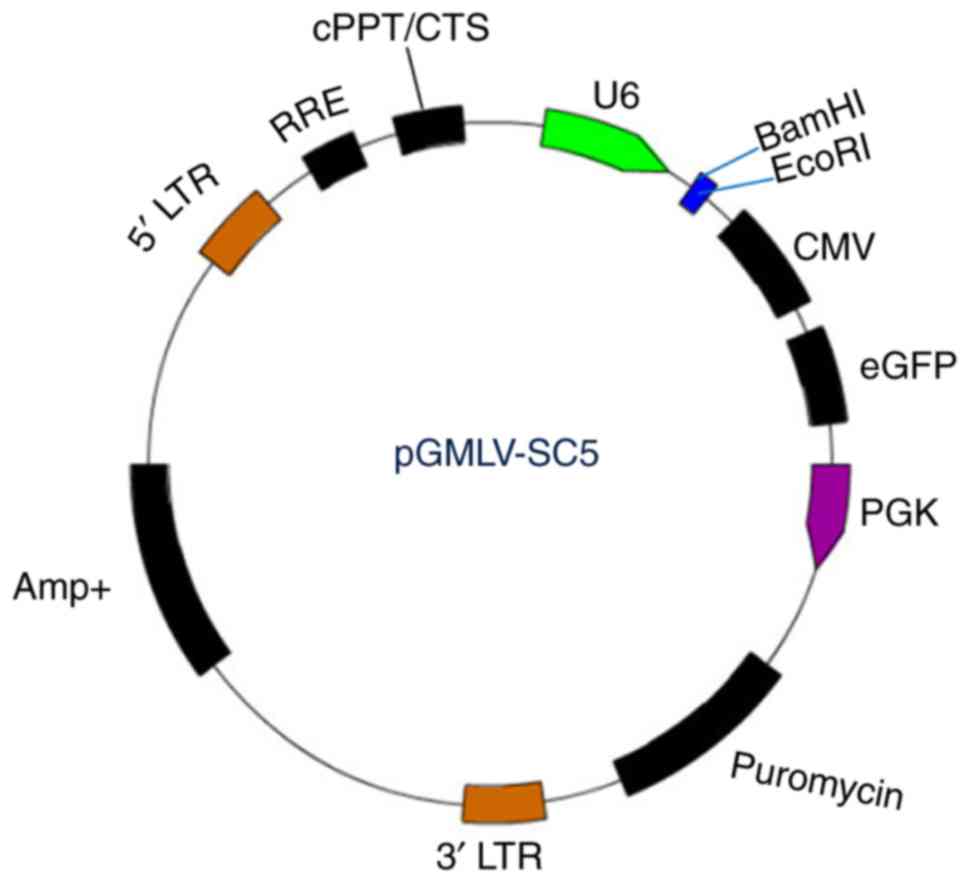

pGMLV-SC5 RNAi lentiviral vector (Fig. 1) was purchased from Genomeditech

(Shanghai, China). We followed the criteria described by Invitrogen

(Carlsbad, CA, USA) to design multiple shRNAs targeting hnRNP A2/B1

or negative control mRNA sequence. Four of the positive targeting

sequences and one negative shRNA against hnRNP A2/B1 sequence

(Table I) were specially chosen for

subsequent studies. Synthesized oligonucleotides (Table II) were annealed and ligated to the

BamHI/EcoRI sites of pGMLV-eGFP to produce

pGMLV-eGFP-shhnRNP A2/B1 or pGMLV-eGFP-shCon, eGFP expression was

used to exhibit the infection of lentiviruses. The HeLa and CaSki

cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1%

penicillin-streptomycin liquid and 1% L-glutamine at 6-well plate.

When the cells were in exponential growth phase, the medium of the

negative control of HeLa or CaSki cells were replaced by medium

with NC-shRNA diluent and the positive group were replaced by

medium with hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA diluent. After 24 h, the culture

media was replaced with RPMI-1640 medium, and cells were incubated

in an incubator for 72 h. HeLa and CaSki were further screened in

media consisting of puromycin (2 mg/l). Because pGMLV-SC5RNAi

lentiviral vector contains eGFP and anti-puromycin gene, the cells

transfacted with lentiviral vector can reveal green fluorescence.

Then the eGFP-positive cells can be picked up for further

analysis.

| Table I.Four specific target sequences of

hnRNPA2/B1 gene. |

Table I.

Four specific target sequences of

hnRNPA2/B1 gene.

| No. | TargetSeq |

|---|

| 1 |

CAGAAATACCATACCATCAAT |

| 2 |

TGACAACTATGGAGGAGGAAA |

| 3 |

GGGCTCATGTAACTGTGAAGA |

| 4 |

GCTTTGTCTAGACAAGAAATG |

| NC-shRNA |

TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT |

| Table II.Oligos of 4 pairs of shRNA and 1 pair

of NC-shRNA. |

Table II.

Oligos of 4 pairs of shRNA and 1 pair

of NC-shRNA.

| Oligo | Oligonucleotide DNA

sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|

|

3935hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA1-T

(EcoRI) |

gatccGCAGAAATACCATACCATCAATCTCGAGATTGATGGTATGGTATTTCTGTTTTTTg |

|

3935hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA1-B

(BamHI) |

aattcAAAAAACAGAAATACCATACCATCAATCTCGAGATTGATGGTATGGTATTTCTGCg |

|

3936hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA2-T

(EcoRI) |

gatccGTGACAACTATGGAGGAGGAAACTCGAGTTTCCTCCTCCATAGTTGTCATTTTTTg |

|

3936hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA2-B

(BamHI) |

aattcAAAAAATGACAACTATGGAGGAGGAAACTCGAGTTTCCTCCTCCATAGTTGTCACg |

|

3937hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA3-T

(EcoRI) |

gatccGGGCTCATGTAACTGTGAAGACTCGAGTCTTCACAGTTACATGAGCCCTTTTTTg |

|

3937hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA3-B

(BamHI) |

aattcAAAAAAGGGCTCATGTAACTGTGAAGACTCGAGTCTTCACAGTTACATGAGCCCg |

|

3938hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA4-T

(EcoRI) |

gatccGCTTTGTCTAGACAAGAAATGCTCGAGCATTTCTTGTCTAGACAAAGCTTTTTTg |

|

3938hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA4-B

(BamHI) |

aattcAAAAAAGCTTTGTCTAGACAAGAAATGCTCGAGCATTTCTTGTCTAGACAAAGCg |

| NC-shRNA1-1 |

gatccGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACTTTTTTACGCGTg |

| NC-shRNA1-2 |

aattcACGCGTAAAAAAGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTCTCTTGAAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACg |

Quantitative real-time PCR

analysis

HeLa and CaSki cells were transfected with either

control or hnRNP A2/B1 shRNAs as described previously, total RNA

was extracted by trizol (Invitrogen), cDNAs were synthesized from

total RNAs by SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time

PCR was performed by SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems,

USA). The specific primers for cDNA were as follows: hnRNP A2/B1,

sence: 5′-GATGGCAGAGAACGGTGTGAAG-3′, and antisense,

5′-AGGCATAGGTATTGGCAACTGC-3′. β-actin, sence:

5′-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3′, antisence:

5′-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3′. β-actin was considered as an internal

control. PCR reaction conditions were perfomed as follows: 95°C for

10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec. The

respective gene expression were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt

method.

Western blot analysis

HeLa and CaSki cells and nude mouse tumor tissues

were lysed by RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% PMSF and 1% protein

phosphatase inhibitor for 30 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g

at 4°C for 20 min. Collecting the supernatant to store at −80°C.

The protein concentration was performed by Bradford assay kit.

Cells and tissue lysates were electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE and

proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore) and then

blocked with Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 with 5% non-fat milk for

2 h. Next, they were incubated with primary antibodies diluted with

TBST overnight at 4°C, the primary antibodies were as follows:

Anti-hnRNP A2/B1 (Bioworld Technology, St. Louis Park, MN, USA;

1:1,000), anti-AKT (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:500), anti-p-AKT

(Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; 1:1,000), anti-p21

(Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:2,000), anti-p27 (Abcam; 1:1,000),

anti-PI3K (Wanleibio, Shenyang, China; 1:500), anti-caspase-3

(Wanleibio; 1:500), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Wanleibio; 1:500),

β-actin (Bioss, Beijing, China; 1:6,000) was used as a loading

control and followed by incubation with secondary antibody

(ZSGB-Bio, Beijing, China; 1:90,000) at room temperature for 1 h.

Chemiluminent detection was determined by ECL kit. ImageJ software

was used to conclude data.

Cell proliferation assay

HeLa and CaSki with hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA, NC-shRNA and

control group cells were digested by 0.25% trypsin (Gibco), diluted

to 5×104/ml and the single cell was suspended in 200 µl

culture medium and then seeded in 96-well plates to culture in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C overnight. Subsequently, the

medium was respectively replaced by 200 µl of new medium that

consisted of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1, Prospec-Tany

Technogene Ltd., Rehovot, Israel) and LY294002 (Beyotime

Biotechnology Corporation, Shanghai, China) or not for 12, 24, 48

h. The concentration of IGF-1 on HeLa and CaSki cells was 100

ng/ml, the concentration of LY294002 on HeLa and CaSki cells was 20

and 15 µM, respectively. Then the culture medium was removed before

the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

(MTT) solution (5 mg/ml) was added to the medium and maintained at

37°C for 4 h, the supernatant was removed and 150 µl DMSO was added

to each well under the absorbance measurement at 490 nm.

Colony formation assay

Single-cell suspensions were digested with 0.25%

trypsin, harvested and seeded into 6-well plates for 500 cells per

well and then cultured in RPMI-1640 in a 5% CO2

incubator at 37°C for two weeks. The cell supernatants were removed

and washed twice with PBS after visible colonies appeared. Cells

were cultured with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min then stained with

moderate gentian violet solution for 30 min before being washed

with PBS. The efficiency of the assay was estimated as follows:

Clone forming efficiency = number of colonies/number of inoculated

cells ×100%.

Cell invasion assay

The invasion of HeLa and CaSki cells was estimated

by transwell chambers. Serum free medium and matrigel (1:4)

solution (60 µl of 4°C) was added to upper chambers for 4–5 h at

37°C. The 200 µl single-cell suspensions (2×105/ml) were

seeded into upper chamber and the lower chambers were fixed with

10% medium to incubate for 24 h. The chamber which was fixed in

100% methanol was taken out and subsequently stained with 2%

crystal violet for 30 min. The cell invasion assay was performed by

the stained cells in the chamber.

Wound healing assay

Single-cell suspensions were diluted to

5×105 per well and seeded into 6-well plates

subsequently cultured with serum-free medium overnight. Then the

adherent cells were washed with PBS 3 times and exposed in

different drugs, respectively, for 0 and 24 h after the cells were

scratched by 10 µl pipette tip across the center of the well. The

gap distance was photographed by microscopy. ImageJ was used to

assess quantitative data.

Cell cycle assay

The exponential phase of HeLa and CaSki cells were

added with 0.25% trypsin for digestion, collected, centrifuged at

100 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol after

supernatant was removed and then suspended in 50 µg/ml RNaseA

(KeyGen Biotech Corp., Ltd., Jiangsu, China) at 37°C for 30 min and

stained in 50 µg/ml PI (KeyGen Biotech Corp., Ltd.) solution for 30

min in the dark. The single-cell suspensions were performed by flow

cytometry.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cells in the exponential phase were digested and

diluted to a 5×104/ml suspension and seeded into 6-well

plates overnight. Subsequently, 5×105 single-cell

suspension was collected with 500 µl Binding Buffer, then fixed

with 5 µl Annexin APC (KeyGen Biotech Corp., Ltd.) and 5 µl PI

(KeyGen Biotech Corp., Ltd.) staining solution in the dark for 15

min. Apoptosis of different cells were evaluated by flow

cytometry.

IC50 of HeLa and CaSki by MTT

assay

Cells (5×104/ml) were harvested and

seeded in 96-well plates, exposed in different concentrations of

lobaplatin or irinotecan (concentration was determined by

pre-experimentation and referenced to the data of published

(18–20), final concentration: 2, 4, 6, 8, 12

and 16 µg/ml or 20, 40, 60, 80, 160 and 240 µg/ml, Hainan Changan

International Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Hainan, China) in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24 h, the test wells were

six-replica. Then each well was fixed with 10 µl per well

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT)

(final concentration: 5 µg/ml) for 4 h. Subsequently, the media was

removed and 150 µl per well of DMSO was added before it was

measured at 490 nm by an enzyme standard instrument. This was

repeated three times and the average value was taken.

Tumor xenograft experiment

Female BALB/c nude mice at 4 weeks were purchased

from Chongqing National Bio Industrial Base Experimental Animal

Center (Chongqing, China). HeLa cells (2×106/ml) were

collected and suspended in 200 µl PBS. The cell suspensions were

injected subcutaneously into the right side near the back of the

neck, all of the nude mice were kept in a homeothermic and specific

pathogen-free room, temperature and humidity were maintained at

26–28°C and 40–60%. Nude mice were randomly divided into 3 groups

(7 mice per group), Vernier caliper was performed to measure tumor

volume every 3 days. All the nude mice were sacrificed by breaking

the neck after anesthetized by 10% chloral hydrate and tumor

tissues were collected for the next analysis after 30 days. The

tumor volume calculation method referred to the following formula:

(LxW2)/2 (21), where L

is the longest tumor diameter and W is the shortest tumor diameter.

Animal experiments were strictly as the guidelines of Guizhou

Medical University Animal Care Welfare Committee (number:

1702256).

Immunohistochemistry

The expression of PCNA and Ki-67 in nude mice

injected with HeLa cells were revealed by immunohistochemistry

assay. Fresh tissues were soaked in 4% neutral formaldehyde for 24

h and then dehydrated and paraffin-embedded, the adhesion slides

with 4-µm sections were kept at 60°C for 4 h. Deparaffinizing with

xylene and hydrating with an ethanol gradient. Followed by citrate

buffer under high pressure to repair the antigen for 3 min and then

the slides were incubated with 0.3% H2O2 for

30 min. After that, the sections were rinsed by PBS-T (PBS with 1%

Tween-20) and were blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 min at 37°C.

Subsequently, the sections were treated with rabbit polyclonal

anti-PCNA (Bioss; 1:100) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki-67 (Bioss;

1:100) at 4°C overnight. According to the recommendation of the

antibody specification, positive tissue sections of PCNA (rat

liver) and Ki-67 (mouse placenta tissue) were used as control, with

PBS instead of primary antibody treated as a negative control.

After successfully completing the previous steps, the sections were

incubated with a secondary antibody for 20 min at 37°C and then

3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) color reagent was added followed by

hematoxylin staining. The slides were dehydrated and then mounted

in neutral resins. Image acquisition was performed by microscope

and Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software was used to analyze the Integrated

Option Density (IOD) values of the brown area and then the IOD

values of each group were statistically analyzed.

H&E staining

The pretreatment of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining was basically the same as the immunohistochemical steps.

Sections (4 µm) were treated with hematoxylin reagent for 5 min

after deparaffinization and rehydration and then treated with 1%

acid-ethanol for 1 sec. Subsequently, the sections were stained by

eosin reagent for 3 min. The slides were dehydrated and mounted

then photographed by microscopy.

Statistical analysis

The data was collected and expressed as means ± SD.

SPSS.23.0 software was used for statistical analysis. All of the

experiment were repeated three times and the average value was

taken. The comparison of the means of two groups was analyzed by

Student's t-test. For all of the differences, P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

hnRNP A2/B1 is significantly

downregulated by lentivirus-mediated shRNA in HeLa and CaSki

cells

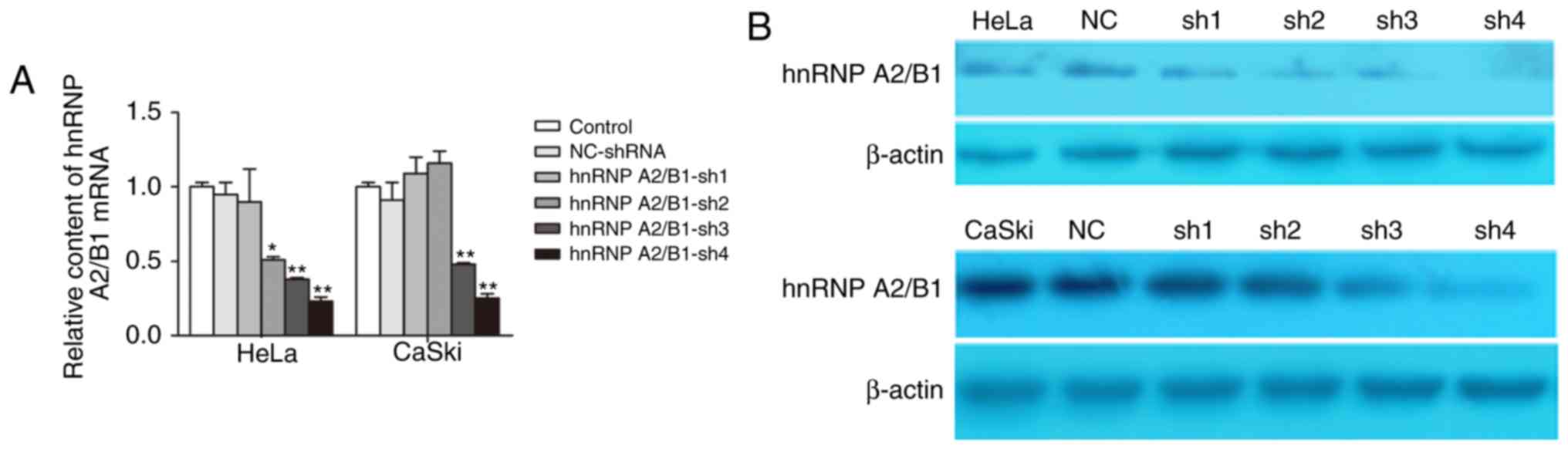

qRT-PCR and western blot were used to evaluate the

efficiency of hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown by lentivirus-mediated shRNA.

The results showed that the expression of hnRNP A2/B1 was highly

suppressed at both mRNA and protein levels. We designed 4 hnRNP

A2/B1-shRNA, the results of qRT-PCR indicted that the best

inhibition efficiency was HeLa-shRNA4 (76.58±3.55%) and

CaSki-shRNA4 (74.79±3.38%) (Fig.

2A). Western blot showed that protein expression of hnRNP A2/B1

in HeLa-shRNA4 (73.25±2.78%) and CaSki-shRNA4 (85.74±6.52%) was

markedly decreased compared to levels in other shRNA and NC-shRNA

group (Fig. 2B). These results

confirmed that the hnRNP A2/B1 was significantly knoced down in

HeLa and CaSki cells which were used for further experiments.

Inhibition of proliferation and colony

formation in cervical cancer cells via hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown

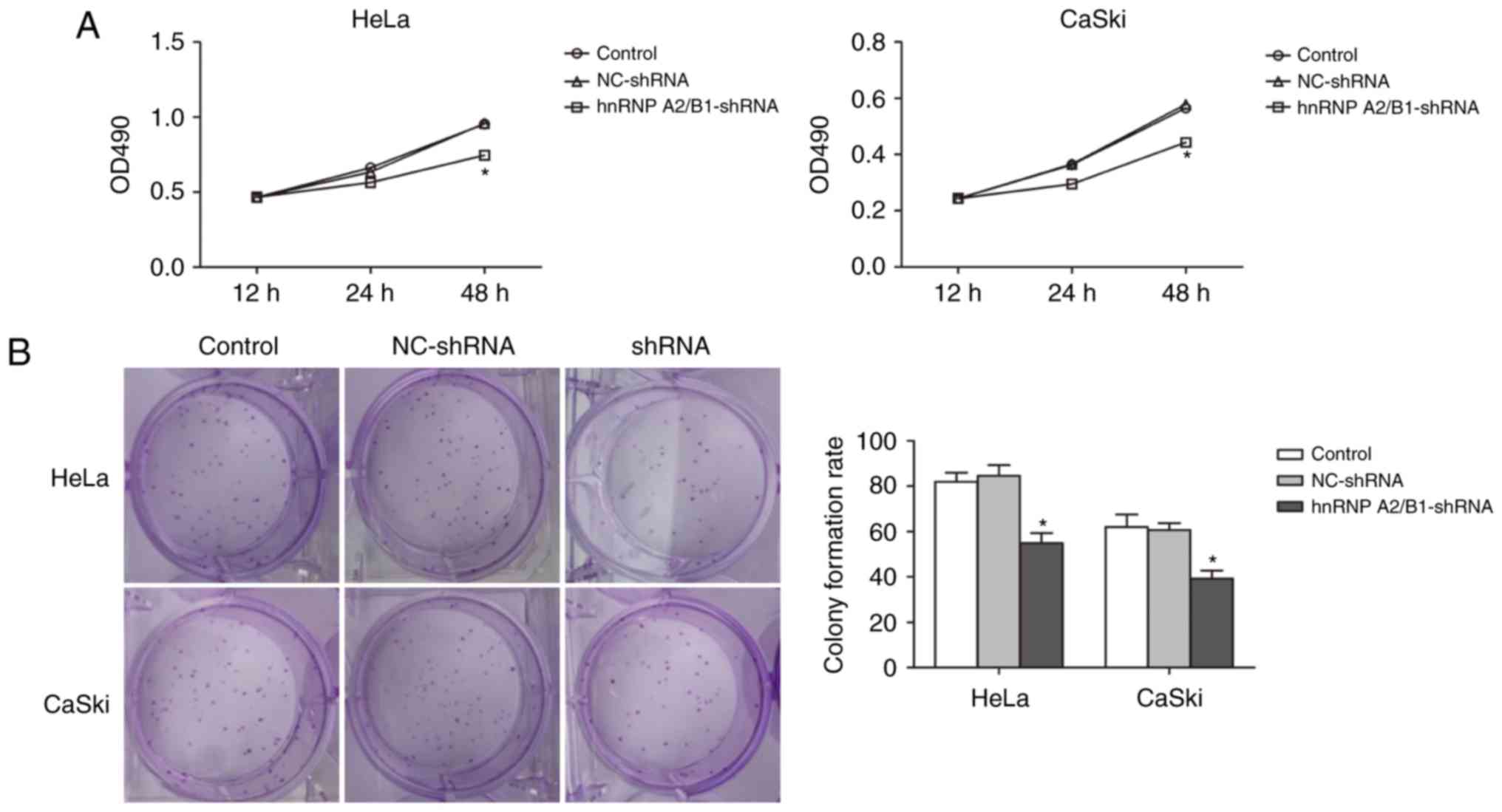

MTT assay was used to demonstrate the relationship

between suppression of hnRNP A2/B1 and cell proliferation (Fig. 3A). Absorbance value was measured in

HeLa and CaSki cells at 12, 24 and 48 h. The absorbance value of

hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA in HeLa and CaSki cells significantly decreased

compared with NC-shRNA and blank control group at 48 h suggesting

successful inhibition of cell proliferation in hnRNP A2/B1

knockdown cell lines.

In addition, colony formation efficiency was

decreased in both hnRNP A2/B1 shRNA-treated HeLa and CaSki cell

lines, as shown by the colony formation assay (Fig. 3B). An at least 30% drop in the

colony formation rate was observed in HeLa hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA cells

as compared to HeLa blank control or HeLa NC-shRNA cells

(55.00±4.35 vs. 82.00±4.00 or 84.67±4.61). The colony formation

rate was also decreased by more than 35% in CaSki hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA

cells as compared to CaSki blank control or CaSki NC-shRNA cells

(39.33±3.50 vs. 62.00±5.57 or 60.67±3.05). No significant

difference between NC-shRNA and blank control group was

observed.

Inhibition of migration and invasion

in HeLa and CaSki cells after hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown

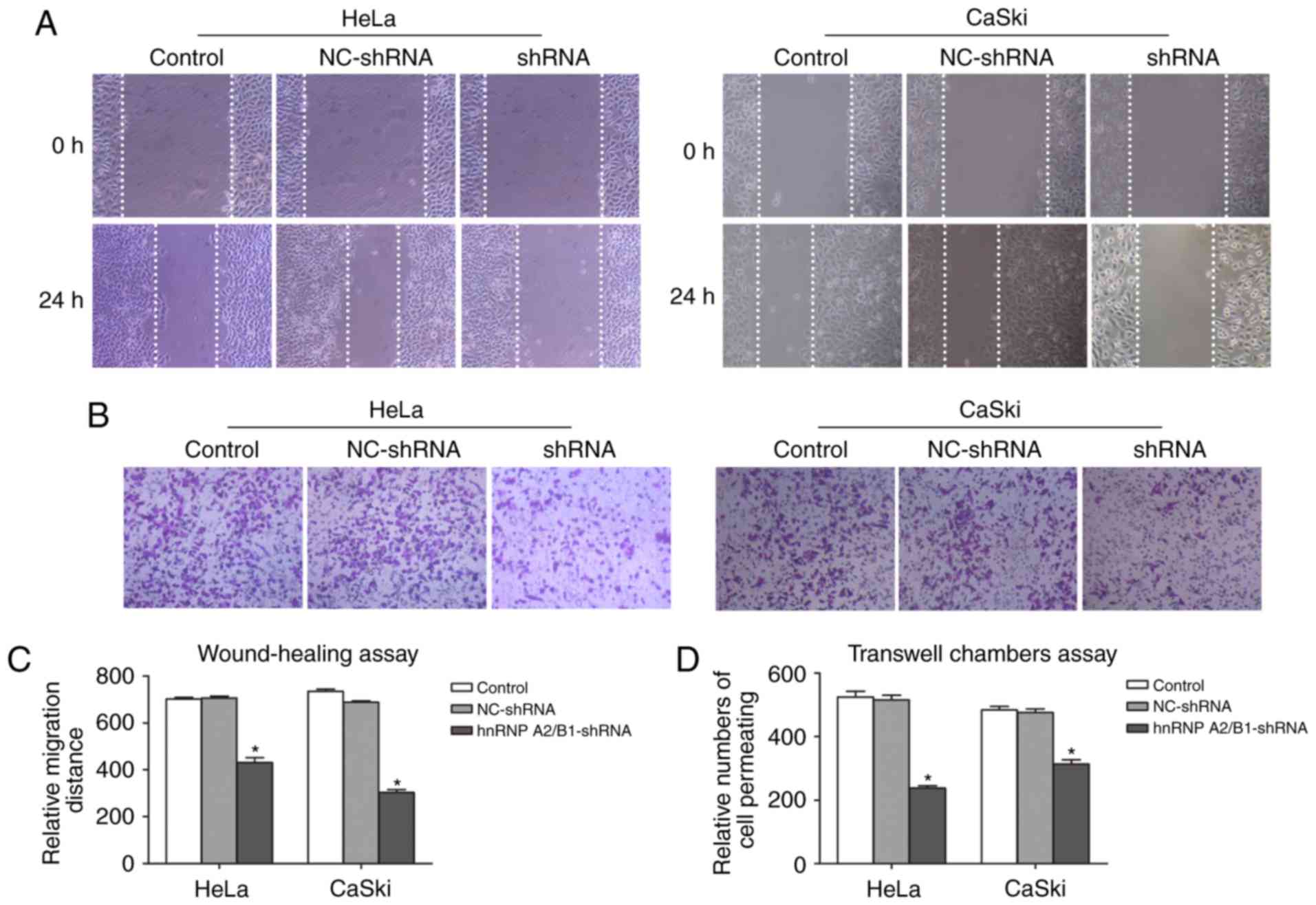

The migration defect mediated by knockdown hnRNP

A2/B1 in HeLa and CaSki cells were performed by wound-healing assay

(Fig. 4A and C). Cell motility

potential in hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA in HeLa and CaSki cells was

significantly decreased compared with NC-shRNA and blank control

group. For HeLa cells, the relative migration rate of hnRNA

A2/B1-shRNA cells was 431.33±20.03 as compared to 702.00±7.21 or

707.33±7.57 of blank control or NC-shRNA cells. For CaSki cells,

the relative migration rate was halved in hnRNA A2/B1 knockdown

cells as compared to blank control or NC-shRNA group (303.33±12.22

vs. 735.33±8.33 or 688.00±6.00).

Transwell chamber assay was used to exhibit invasion

ability (Fig. 4B and D). In both

cell lines, the number of cell permeating in hnRNA A2/B1 knockdown

cells dropped significantly from blank control or NC-shRNA cells

(237.67±7.51 vs. 524.67±17.5 or 515.33±15.01 in HeLa cells;

313.67±13.05 vs. 483.67±10.97 or 476.00±11.00 in CaSki cells) and

again we did not observe a significant difference between blank

control and NC-shRNA groups for either cell line.

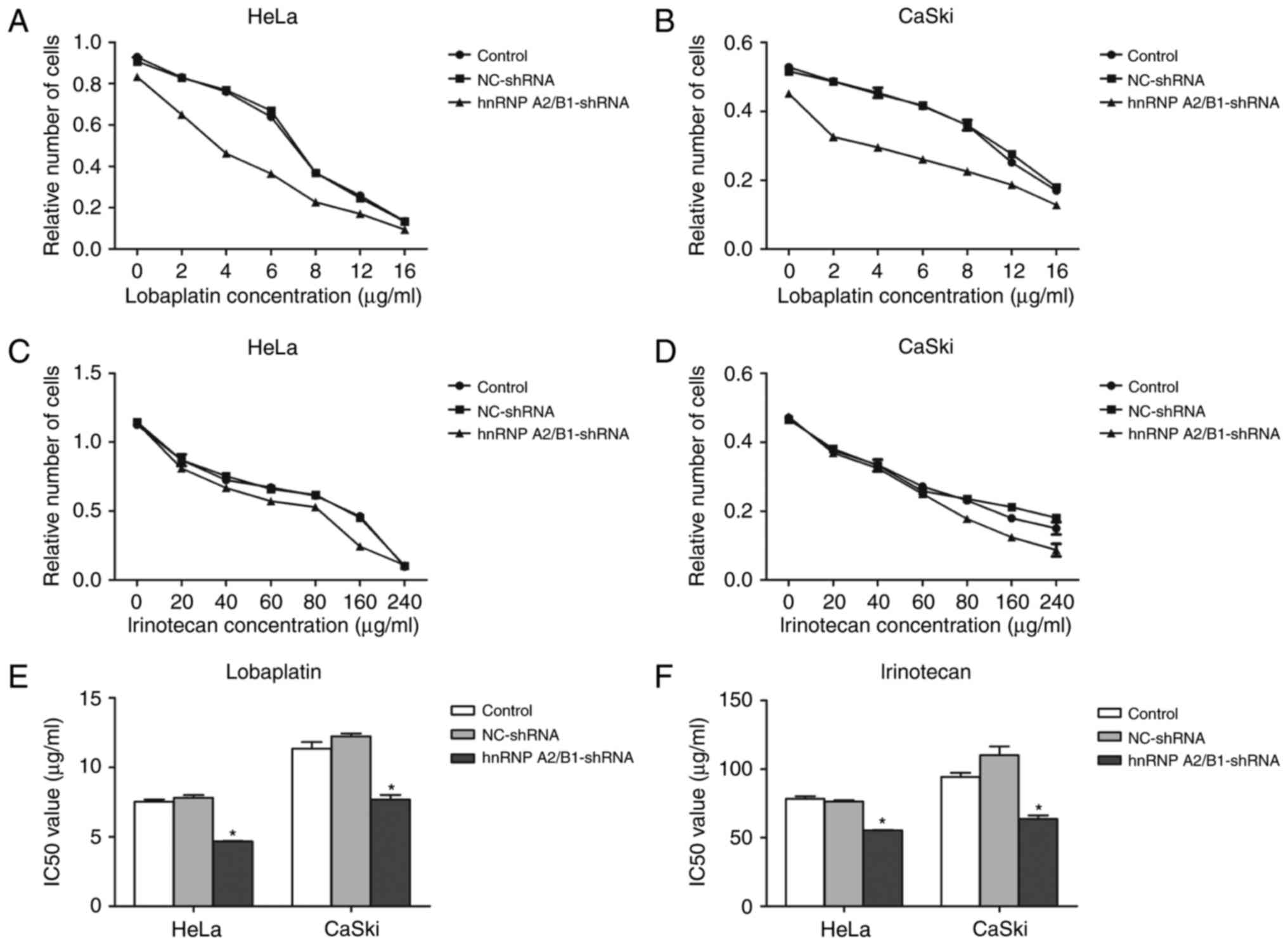

The enhancement of chemotherapy

sensitivity of lobaplatin or irinotecan by suppression of hnRNP

A2/B1 in HeLa and CaSki cells

The IC50 value of lobaplatin or

irinotecan in HeLa and CaSki cells was detected by MTT assay. The

IC50 of lobaplatin in HeLa blank control, HeLa NC-shRNA

and HeLa hnRNPA2/B1-shRNA was 7.526±0.17, 7.816±0.19, 4.669±0.03

µg/ml, respectively. The IC50 value of blank control

group, NC group, shRNA group was 11.340±0.49, 12.240±0.20 and

7.677±0.34 µg/ml in lobaplatin treated CaSki cells. The

IC50 of irinotecan in HeLa blank control group and HeLa

NC-shRNA group were 78.487±1.69 and 76.277±1.09 µg/ml, CaSki blank

control group and CaSki NC-shRNA group was 94.250±3.05 and

110.233±6.38 µg/ml, but the hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA group of HeLa and

CaSki cells were decreased significantly to 55.447±0.224 and

63.593±2.76 µg/ml. The IC50 value of lobaplatin and

irinotecan in HeLa and CaSki cells had no statistical significance

between NC-shRNA group and blank control group (Fig. 5A-F). The results indicate that

inhibition of hnRNP A2/B1 boosts the sensitivity of cervical cancer

lines towards lobaplatin and irinotecan.

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway plays an

important role in hnRNP A2/B1-regulated cell cycle and apoptosis in

cervical cancer cell lines

Flow cytometry was used to investigate the effect of

hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown on cell cycle distribution in HeLa and CaSki

cells. The proportion of G1 phase cells in hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown

HeLa and CaSki cells was significantly increased (Fig. 6A and Table III). No significant difference was

seen between NC-shRNA group and blank control group in HeLa or

CaSki cells.

| Table III.The influence of hnRNPA2/B1 on the

cell cycle (n=3, x±s). |

Table III.

The influence of hnRNPA2/B1 on the

cell cycle (n=3, x±s).

| Group | G (%) | S (%) |

|---|

| CaSki |

57.56±0.75 |

42.52±0.22 |

| CaSki-shRNA |

60.57±0.14a |

38.35±0.36 |

| CaSki-NC |

57.36±0.55 |

42.53±0.16 |

| HeLa |

50.58±0.23 |

49.44±0.21 |

| HeLa-shRNA |

57.23±0.23a |

41.63±0.56 |

| HeLa-NC |

51.21±0.17 |

48.66±0.31 |

We also looked into the relationship between hnRNP

A2/B1 inhibition and cell apoptosis. In both HeLa and CaSki cell

lines, the apoptosis rate was increased after hnRNP knockdown as

compared to blank control or NC groups (25.53 vs. 11.83% or 14.01%

in HeLa cells; 46.20 vs. 12.40% or 11.97 in CaSki cells); (Fig. 6B). The apoptosis rate was similar in

the two control groups for both cell lines.

We further tested the change of PI3K/AKT pathway

related proteins by Western blot in hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown cervical

cancer cells (Fig. 6C). The hnRNP

A2/B1 knockdown group showed the upregulation of p21, p27 and

cleaved caspase-3 and downregulation of p-AKT (P<0.05). However,

there is no obvious change in the expression level of PI3K and AKT

in the knock-down cell lines.

Effects of hnRNPA2/B1 knockdown cells

treated with IGF-1 and LY294002, respectively, or not on the

activation or inhibition of PI3K/AKT pathway

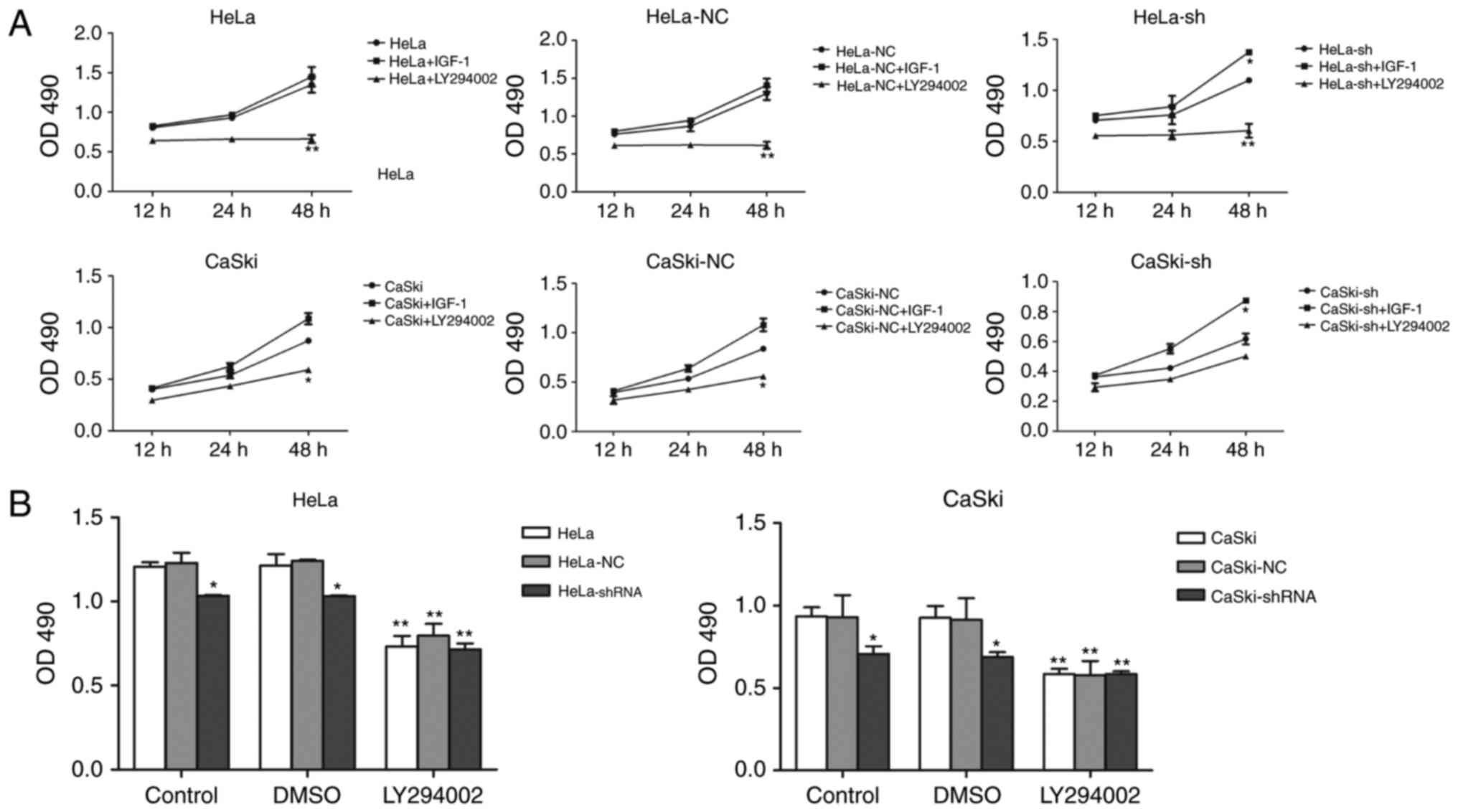

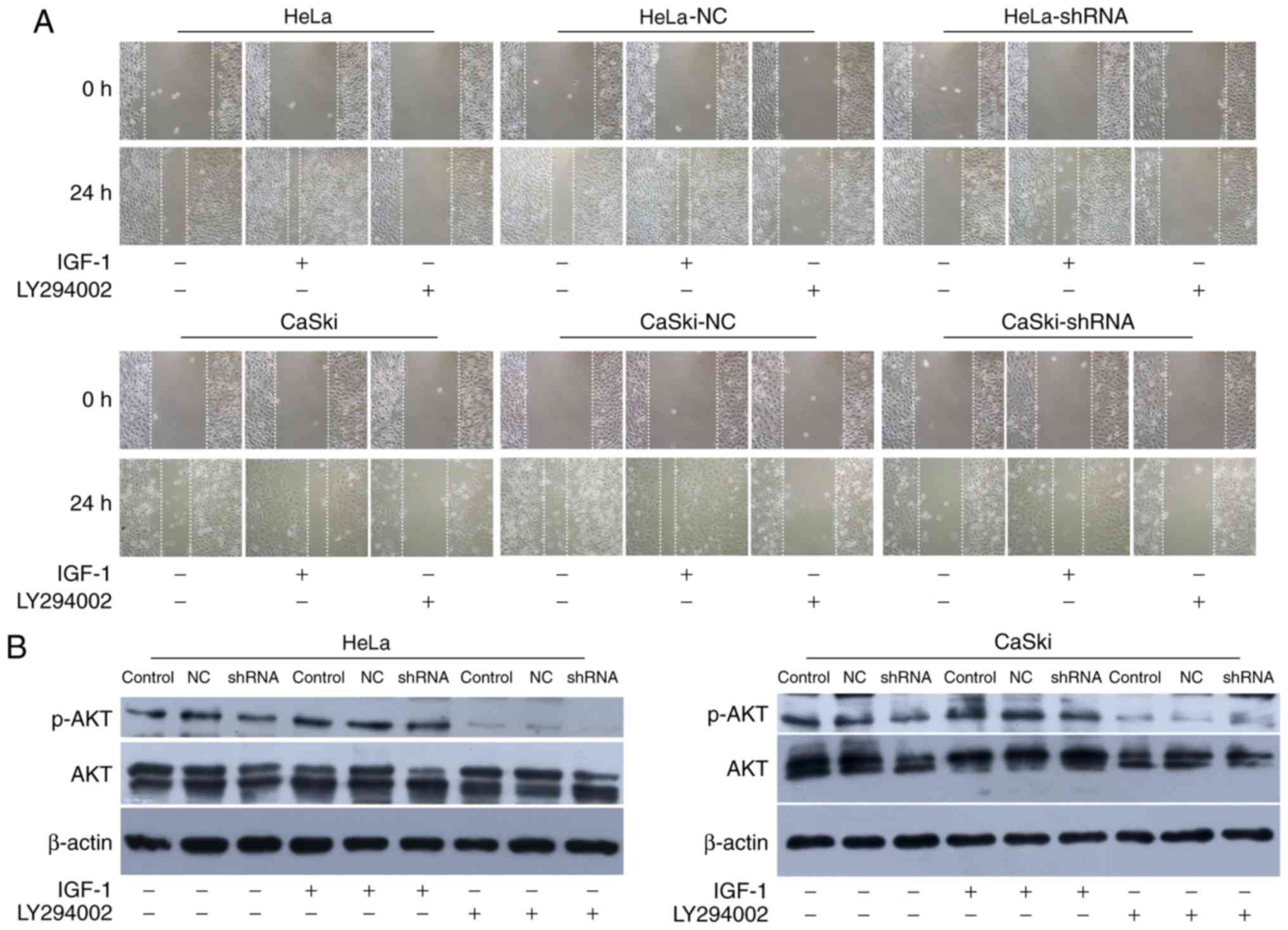

To further illustrate the relationship between hnRNP

A2/B1 and PI3K/AKT pathway, IGF-1 and LY294002 were used as agonist

and inhibitor of the PI3K/AKT pathway. MTT assay and wound healing

assay were used to investigate the proliferation and migration of

HeLa and CaSki cells after incubated with IGF-1 and LY294002

(Figs. 7A and 8A). The proliferation and migration

phenotype of hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown groups were rescued by IGF-1

treatment while worsened in LY294002 treated group. Validation of

activation or inhibition of PI3K/AKT pathway after exposed to IGF-1

or LY294002 was performed by western blotting (Fig. 8B). The expression of p-AKT was

significantly reduced after cultured in LY294002, while the

expression of p-AKT was increased both in HeLa and CaSki cells

after exposed in IGF-1 (P<0.01). The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was

dissolved in DMSO solution, so the same amount of DMSO was added

into cells as the vehicle control group to avoid interference with

the experiment. The PI3K activator IGF-1 was reconstituted in

sterile 18M Omega-cm H2O according to instruction and so

no vehicle control group in this drug. The proliferation of HeLa

and CaSki cells at 48 h after cultured with DMSO was investigated

by MTT assay (Fig. 7B), the DMSO

group had no significant change compared to the non-medicated

group.

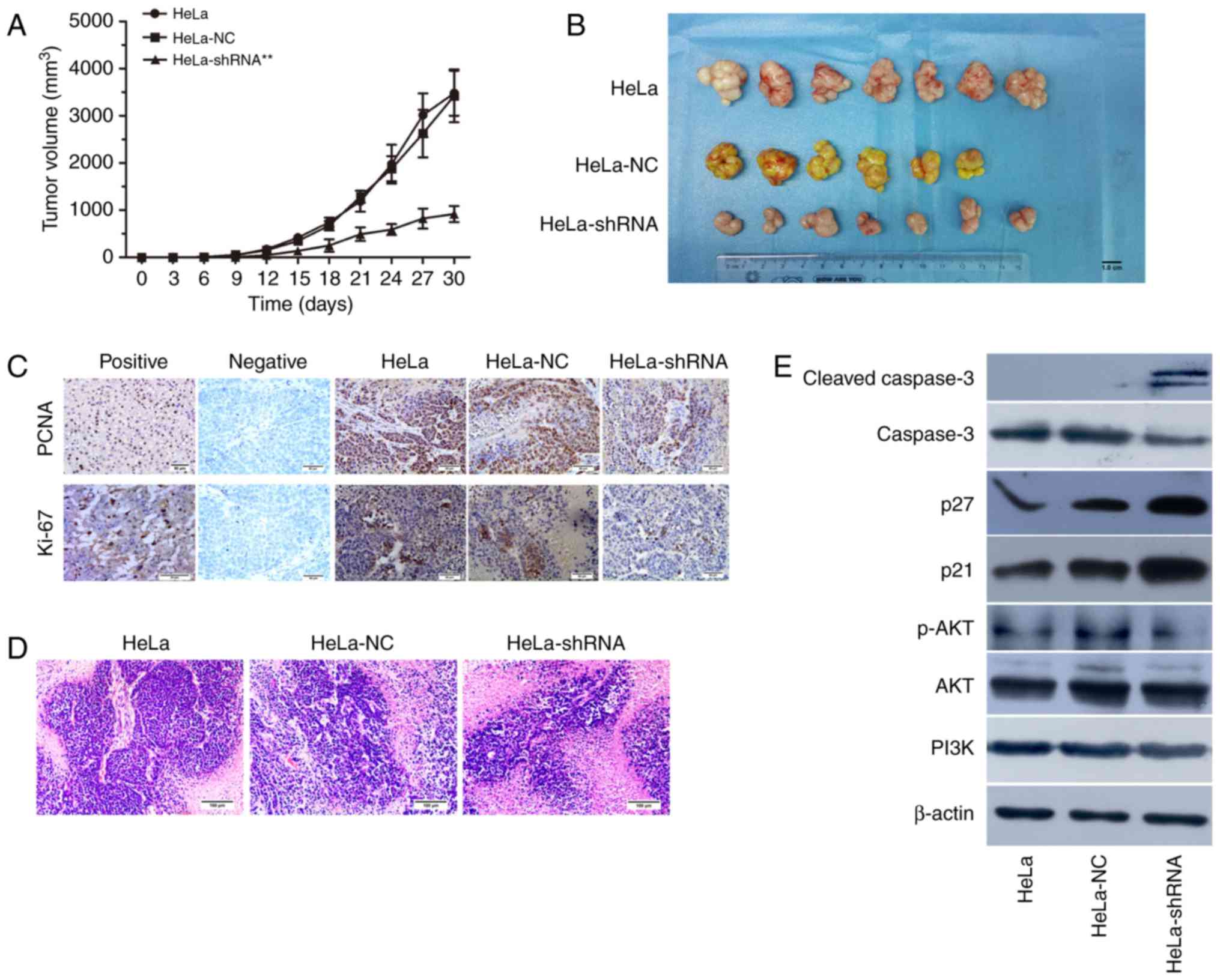

Effect of hnRNPA2/B1 silencing on nude

mouse xenograft in vivo

To determine the effect of hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown

in vivo, the transfected HeLa cells were injected into nude

mice to establish a tumor xenograft model. The nude mice were

randomly divied into 3 groups for injection with HeLa, HeLa-NC

shRNA and HeLa-hnRNP A2/B1 shRNA, respectively. Since a nude mouse

of NC group was dead before inoculating tumor cells, the survival

rate of nude mice injected with tumor cells was 100% and behavior

was normal throughout the experiment. The results showed that the

incidence of tumorigenesis in hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA transfected HeLa

cells injected group was significantly lower compared to the

control and NC-shRNA group (Fig. 9A and

B). To demonstrate whether the proliferation capacity was

consistent with the previous experiment results in vitro,

immunohistochemistry was used to confirm the expression of PCNA and

Ki-67 in vivo and the brown particles were labeled as

positive areas. In addition, H&E staining was used to observe

the morphological structure in tumor tissues. The results suggested

that the positive expression of PCNA (P<0.05) and Ki-67

(P<0.01) were significantly lower in hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown tumor

group compared to the other group (Fig.

9C and Table IV). As shown in

Fig. 9D, the characteristics of

xenograft tissues conformed to tumor cells and were as follows:

Acidophil hepatocytes with both nuclear and cytoplasmic

enlargement, nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia, and frequent

multinucleation. In order to further demonstrate the relationship

between the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and hnRNP A2/B1 in nude

mouse xenograft tissues, western blotting was used for

clarification. The xenograft tumor of hnRNP A2/B1-shRNA group could

suppress the expression of p-AKT protein, upregulating cleaved

caspase-3, p21 and p27 (Fig. 9E).

The results indicated that it was consistent with the earlier

apoptotic and cycle results in vitro from the protein level

of xenograft tumor tissues.

| Table IV.The IOD values of PCNA and Ki-67

(x±s). |

Table IV.

The IOD values of PCNA and Ki-67

(x±s).

| Group | PCNA | Ki-67 |

|---|

| HeLa |

163256.50±38370.00 |

43485.35±26291.10 |

| HeLa-NC |

151597.80±33089.76 |

43102.09±12737.12 |

| HeLa-shRNA |

75461.77±22288.53a |

13669.97±4926.23b |

Discussion

hnRNP A2/B1 is a set of primer-mRNA binding proteins

involved in cell transcription and protein translation. Previous

studies suggested that uncontrolled expression of hnRNP A2/B1 is

one of the reasons for promoting tumor formation and thus highly

expressed in a variety of cancers (9,22–26).

Some recent studies suggested that hnRNP A2/B1 is a proto-oncogene,

especially in non-small cell lung cancer, the expression of hnRNP

A2/B1 may be used as the reference index for evaluating the status

and prognostic indicator of disease (27). The functional role of hnRNP A2/B1 in

cervical cancer is rarely reported. Following previous reports, we

used cervical cancer cell lines HeLa and CaSki cells with hnRNP

A2/B1 knockdown by shRNA as a model to study the role of hnRNP

A2/B1 in cervical cancer.

hnRNPA2/B1, as a new focus of cancer-associated

tumor antigen has gradually attracted scientists' attention. A

study by Sinha and colleague showed that hnRNP A2/B1 may be

combined with the telomere repeated sequence TTAGGG to protect the

telomere from destruction by ribozyme (28). To investigate how to interrupt these

factors, receptor and oncogene signaling pathway to inhibit cancer

cell proliferation, invasion and migration has become one of the

main strategies for the development of new anticancer drugs. As

before, hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown in this study suggested that the

proliferation of cervical cancer cell lines was markedly decreased

compared to the control group. The proliferation-related antigen

PCNA and Ki-67 were also significantly reduced after hnRNP A2/B1

knockdown in vivo. According to previous studies,

proliferation-related antigen Ki-67 and proliferating cell nuclear

antigen (PCNA) are proteins that are present in the cell

proliferative phase and are one of the markers of proliferating

cells (29). Similarly, our study

also showed that hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown could inhibit cell colony

formation. Upregulated proliferation of cancer cells is one of the

mechanism of tumor growth and is the basis of the occurrence and

development of cancer cells (30,31).

Previous data reported that hnRNP A2/B1 plays an

important role in the regulation of the migration, invasion and

drug resistance in partial cancer cells. In addition, the process

of therapy resistance during the development of pancreatic cancer

is related to the high expession of hnRNPA2/B1 (32–35).

This study showed that the inhibition of hnRNP A2/B1 in cervical

cancer cell lines could decrease the ability of migration and

invasion. After chemotherapy with lobaplatin and irinotecan

respectively, the IC50 value was significantly reduced

in hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown group, these results also confirmed

previous research conclusions. This suggests that hnRNP A2/B1 in

cervical cancer is associated with drug sensitivity and may be one

of the mechanism in enhancement of therapy sensitivity by hnRNP

A2/B1 knockdown.

Silencing hnRNP A2/B1 resulted in G1/S cell cycle

arrest and accumulation of G0/G1 phase cells (36). The restriction point of cell cycle

at G1/S transition is particularly important and determines the

conversion of cell cycle time, the number of S phase and G2/M phase

cell proportion can reflect the state of cell proliferation,

suggesting active cell growth. The upregulation of checkpoint in

cell cycle is closely related to the occurrence of tumors which

induce cell apoptosis (37), and

another study also suggested that hnRNP A2/B1 can regulate the

expression of p14 and p16 and activate cyclin-dependent kinase 4 to

assure the transition between G1 and S phase (38). The levels of S phase and G2/M phase

were decreased in hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown cervical cancer cells which

demonstrated that silencing hnRNP A2/B1 could block cervical cancer

cell cycle in G1 phase to prevent cell proliferation. Moreover, we

indicated that hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown can induce cell apoptosis. p21

and p27, as the inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), plays

an important part in regulation of cell cycle (39,40).

Just as our results, the expression of p21 and p27 were increased

in vitro and vivo at hnRNP A2/B1 downregulation group

and the result suggested that the hnRNP A2/B1 affected cell cycle

by regulated p21 and p27 in cervical cancer. Previous studies

showed that hnRNP A2/B1 can upregulate the proportion of

anti-apoptosis factors and proteins in cells to promote the

malignant growth of tumors (41),

our study also confirmed this argument. Caspase-3 may be involved

in cell apoptosis (42), our

results indicated that silencing hnRNP A2/B1 enhanced apoptosis in

cervical cancer via activation of caspase-3.

Aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is

widespread in malignant tumors and is an important pathway to

mediate cell cycle, and apoptosis (43,44).

Licochalcone A induced autophagy by inactivation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway in cervical cancer cells (45). Activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway

could reflect phosphorylation levels of AKT proteins and after

phosphorylation, it could be further activated a variety of

downstream proteins, such as p21, p27 and caspase-3, which could

regulate the state of tumor cells. Our results demonstrated that

the expression of p-AKT was reduced in hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown group

both in vitro and in vivo and hnRNP A2/B1 was related

to PI3K/AKT pathway in promotion of cervical cancer. Previous

studies have reported that hnRNP A2/B1 regulates the self-renewal,

cell cycle and pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells is

related to PI3K/AKT pathway (46)

and this was similar to our results.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that

inhibiting hnRNP A2/B1 expression in cervical cancer can induce

apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and enhance the chemotherapy

sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to lobaplatin and irinotecan.

Analysis of cervical cancer cell lines HeLa and CaSki cells in

vitro shows that hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown can reduce the ability

of cell proliferation, invation and migration, indicating that

hnRNP A2/B1 may be one of the central regulators for cervical

cancer. The activation of PI3K/AKT pathway is one of the important

mechanisms for hnRNP A2/B1 to facilitate the development of

cervical cancer. Therefore, our study suggests that hnRNP A2/B1 may

be an important molecular target for cancer treatment of cervical

cancer and provide a new direction for clinical treatment of

cervical cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science

Foundation of China (2015–81560481) and The Joint Funds of Science

and Technology Department of Guizhou Province and Affiliated

Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (2015–7410).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

hnRNP A2/B1

|

heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein A2/B1

|

|

qRT-PCR

|

quantitative reverse transcription

polymerase chain reaction

|

|

shRNA

|

short hairpin RNA

|

|

RPMI-1640

|

Roswell Park Memorial

Institute-1640

|

|

MTT

|

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

|

|

PBS

|

Phosphate buffere saline

|

|

IC50

|

half maximal inhibitory

concentration

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethylsulphoxide

|

|

SDS

|

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

|

|

PI3K/AKT

|

phophatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein

kinase-B

|

|

CDK

|

cyclin dependent kinase

|

|

IGF-1

|

insulin-like growth factor 1

|

|

PCNA

|

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin and eosin

|

|

DAB

|

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

|

|

IOD

|

integrated option density

|

References

|

1

|

Yoysungnoen B, Bhattarakosol P, Changtam C

and Patumraj S: Effects of tetrahydrocurcumin on tumor growth and

cellular signaling in cervical cancer xenografts in nude mice.

Biomed Res Int. 2016:17812082016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S and He J:

Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2011. Chin J Cancer

Res. 27:2–12. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lin WC, Kuo KL, Shi CS, Wu JT, Hsieh JT,

Chang HC, Liao SM, Chou CT, Chiang CK, Chiu WS, et al: MLN4924, a

Novel NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, exhibits antitumor

activity and enhances cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity in human

cervical carcinoma: In vitro and in vivo study. Am J Cancer Res.

5:3350–3362. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Koh WJ, Greer BE, Abu-Rustum NR, Apte SM,

Campos SM, Chan J, Cho KR, Cohn D, Crispens MA, DuPont N, et al:

Cervical cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 11:320–343. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ma X, Zhang J, Liu S, Huang Y, Chen B and

Wang D: Nrf2 knockdown by shRNA inhibits tumor growth and increases

efficacy of chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 69:485–494. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dreyfuss G, Kim VN and Kataoka N:

Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 3:195–205. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kozu T, Henrich B and Schäfer KP:

Structure and expression of the gene (HNRPA2B1) encoding the human

hnRNP protein A2/B1. Genomics. 25:365–371. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

He Y, Brown MA, Rothnagel JA, Saunders NA

and Smith R: Roles of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A

and B in cell proliferation. J Cell Sci. 118:3173–3183. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Patry C, Bouchard L, Labrecque P, Gendron

D, Lemieux B, Toutant J, Lapointe E, Wellinger R and Chabot B:

Small interfering RNA-mediated reduction in heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoparticule A1/A2 proteins induces apoptosis in human

cancer cells but not in normal mortal cell lines. Cancer Res.

63:7679–7688. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Izaurralde E, Jarmolowski A, Beisel C,

Mattaj IW, Dreyfuss G and Fischer U: A role for the M9 transport

signal of hnRNP A1 in mRNA nuclear export. J Cell Biol. 137:27–35.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

He Y and Smith R: Nuclear functions of

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A/B. Cell Mol Life Sci.

66:1239–1256. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kamma H, Horiguchi H, Wan L, Matsui M,

Fujiwara M, Fujimoto M, Yazawa T and Dreyfuss G: Molecular

characterization of the hnRNPA2/B1 proteins: Tissue-specific

expression and novel isoforms. Exp Cell Res. 246:399–411. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Qu XH, Liu JL, Zhong XW, Li XI and Zhang

QG: Insights into the roles of hnRNP A2/B1 and AXL in non-small

cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 10:1677–1685. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Joshi J, Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Galvez A,

Amanchy R, Linares JF, Duran A, Pathrose P, Leitges M, Cañamero M,

Collado M, et al: Par-4 inhibits Akt and suppresses Ras-induced

lung tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 27:2181–2193. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang M, Fang X, Liu H, Guo R, Wu X, Li B,

Zhu F, Ling Y, Griffith BN, Wang S and Yang D: Bioinformatics-based

discovery and characterization of an AKT-selective inhibitor

9-chloro-2-methylellipticinium acetate (CMEP) in breast cancer

cells. Cancer Lett. 252:244–258. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gao N, Flynn DC, Zhang Z, Zhong XS, Walker

V, Liu KJ, Shi X and Jiang BH: G1 cell cycle progression and the

expression of G1 cyclins are regulated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR/P70S6KI

signaling in human ovarian cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol.

287:C281–C291. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Polivka J Jr and Janku F: Molecular

targets for cancer therapy in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Pharmacol

Ther. 142:164–175. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li X, Ran L, Fang W and Wang D: Lobaplatin

arrests cell cycle progression, induces apoptosis and alters the

proteome in human cervical cancer cell line CaSki. Biomed

Pharmacother. 68:291–297. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jang HJ, Hong EM and Lee J, Choi JE, Park

SW, Byun HW, Koh DH, Choi MH, Kae SH and Lee J: Synergistic effects

of simvastatin and Irinotecan against colon cancer cells with or

without Irinotecan resistance. Gastroenterol Res Pract.

2016:78913742016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kodawara T, Higashi T, Negoro Y, Kamitani

Y, Igarashi T, Watanabe K, Tsukamoto H, Yano R, Masada M, Iwasaki H

and Nakamura T: The inhibitory effect of Ciprofloxacin on the

β-Glucuronidase-mediated deconjugation of the Irinotecan metabolite

SN-38-G. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 118:333–337. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ren C, Ren T, Yang K, Wang S, Bao X, Zhang

F and Guo W: Inhibition of SOX2 induces cell apoptosis and G1/S

arrest in Ewing's sarcoma through the PI3K/Akt pathway. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 35:442016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Golan-Gerstl R, Cohen M, Shilo A, Suh SS,

Bakàcs A, Coppola L and Karni R: Splicing factor hnRNPA2/B1

regulates tumor suppressor gene splicing and is an oncogenic driver

in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 7:4464–4472. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shilo A, Ben Hur V, Denichenko P, Stein I,

Pikarsky E, Rauch J, Kolch W, Zender L and Karni R: Splicing factor

hnRNP A2 activates the Ras-MAPK-ERK pathway by controlling A-Raf

splicing in hepatocellular carcinoma development. RNA. 20:505–515.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P and

Manley JL: hnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate

kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 463:364–368. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhao CH, Li QF, Chen LY, Tang J, Song JY

and Xie Z: Expression and localization of hnRNP A2/B1 during

differentiation of human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells induced by HMBA.

Ai Zheng. 27:677–684. 2008.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Katsimpoula S, Patrinou-Georgoula M,

Makrilia N, Dimakou K, Guialis A, Orfanidou D and Syrigos KN:

Overexpression of hnRNPA2/B1 in bronchoscopic specimens: A

potential early detection marker in lung cancer. Anticancer Res.

29:1373–1382. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Etcheverry GJ: 2006 Nobel prize in

physiology or medicine. The silence of genes. Medicina (B Aires).

67:92–95. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sinha P, Poland J, Kohl S, Schnölzer M,

Helmbach H, Hütter G, Lage H and Schadendorf D: Study of the

development of chemoresistance in melanoma cell line using proteome

analysis. Electrophoresis. 24:2386–2404. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bologna-Molina R, Mosqueda-Taylor A,

Molina-Frechero N, Mori-Estevez AD and Sánchez-Acuña G: Comparison

of the value of PCNA and Ki67 as markers of cell proliferation in

ameloblastic tumors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 18:e174–e179.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cotrim P, Martelli-Junior H, Graner E,

Sauk JJ and Coletta RD: Cyclosporin A induces proliferation in

human gingival fibroblasts via induction of transforming growth

factor-beta1. Periodontol. 74:1625–1633. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Stanley G, Harvey K, Slivova V, Jiang J

and Sliva D: Ganoderma lucidum suppresses angiogenesis through the

inhibition of secretion of VEGF and TGF-beta1 from prostate cancer

cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 330:46–52. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Clower CV, Chatterjee D, Wang Z, Cantley

LC, Vander Heiden MG and Krainer AR: The alternative splicing

repressors hnRNP A1/A2 and PTB influence pyruvate kinase isoform

expression and cell metabolism. Proc Nati Acad Sci USA. 107:pp.

1894–1899. 2010; View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Gu WJ and Liu HL: Induction of pancreatic

cancer cell apoptosis, invasion, migration, and enhancement of

chemotherapy sensitivity of gemcitabine, 5-FU, and oxaliplatin by

hnRNP A2/B1 siRNA. Anticancer Drugs. 24:566–576. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tauler J, Zudaire E, Liu H, Shih J and

Mulshine JL: hnRNP A2/B1 modulates epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 70:7137–7147.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang L, Liu HL, Li Y and Yuan P: Proteomic

analysis of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and pancreatic

carcinoma in rat models. World J Gastroenterol. 17:1434–1441. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hallett RM, Huang C, Motazedian A, Auf der

Mauer S, Pond GR, Hassell JA, Nordon RE and Draper JS:

Treatment-induced cell cycle kinetics dictate tumor response to

chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 6:7040–7052. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Montague JW and Cidlowski JA: Cellular

catabolism in apoptosis: DNA degradation and end nuclease

activation. Experientia. 52:857–862. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhu D, Xu G, Ghandhi S and Hubbard K:

Modulation of the expression of p16INK4a and p14AKT by hnRNPA1 and

A2 RNA binding proteins: Implications for cellular senescence. J

Cell Physiol. 193:19–25. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chu I, Sun J, Arnaout A, Kahn H, Hanna W,

Narod S, Sun P, Tan CK, Hengst L and Slingerland J: p27

phosphorylation by Src regulates inhibition of cyclin E-Cdk2. Cell.

128:281–294. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gartel AL and Radhakrishnan SK: Lost in

transcription: p21 repression, mechanisms and consequences. Cancer

Res. 65:3980–3985. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen ZY, Cai L, Zhu J, Chen M, Chen J, Li

ZH, Liu XD, Wang SG, Bie P, Jiang P, et al: Fyn requires hnRNPA2/B1

and Sam68 to synergistically regulate apoptosis in pancreatic

cancer. Carcinogenesis. 32:1419–1426. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zimmermann KC, Bonzon C and Green DR: The

machinery of programmed cell death. Pharmacol Ther. 92:57–70. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Stegeman H, Span PN, Kaanders JH and

Bussink J: Improving chemoradiation efficacy by PI3-K/AKT

inhibition. Cancer Treat Rev. 40:1182–1191. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Manning BD and Cantley LC: AKT/PKB

Signaling: Navigating downstream. Cell. 129:1261–1274. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tsai JP, Lee CH, Ying TH, Lin CL, Hsueh JT

and Hsieh YH: Licochalcone A induces autophagy through

PI3K/Akt/mTOR inactivation and autophagy suppression enhances

Licochalcone A-induced apoptosis of human cervical cancer cells.

Oncotarget. 6:28851–28866. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Choi HS, Lee HM, Jang YJ, Kim CH and Ryu

CJ: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 regulates the

self-renewal and pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells via the

control of the G1/S transition. Stem Cells. 31:2647–2658. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|