Introduction

Wilms tumor is the most common pediatric renal tumor

with a prevalence of ~1 in 10,000 children (1). Although combination therapy has

improved the prognosis for most patients, ~10% of patients with

Wilms tumors experience poor survival due to metastasis and

recurrence (2–5). Hence, it is essential to elucidate the

molecular mechanism underlying the tumorigenesis and metastasis of

Wilms tumors, which could provide predictive and therapeutic

targets for this childhood disease.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of single-stranded,

highly conserved small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene

expression at the post-transcriptional level by binding to the

3′-unstranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, resulting in mRNA

silencing or degradation (6–8). In

tumors, various studies have confirmed that miRNAs function as

oncogenes or tumor suppressors which regulate tumor initiation,

progression and prognosis (9–11). The

expression of miRNAs has been shown to be stable and an excellent

marker for the early diagnosis of tumors (12).

miR-92a-3p is a member of the miR-17-92 family,

which plays a critical role in modulating cell viability, apoptosis

and metastasis of tumor cells (13,14).

In glioma, miR-92a-3p was found to exert various effects on tumor

stem-like cells by targeting the Notch-1/Akt pathway (15). In colorectal adenocarcinoma, the

expression level of miR-92a-3p was able to predict the prognosis of

patients (16). However, the

expression level, clinicopathological and biological functions of

miR-92a-3p in Wilms tumor and its underlying molecular mechanisms

remain unclear. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the

predicted miRNAs and the related molecular mechanisms in Wilms

tumor.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

The gene expression profiles of GSE50505 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE50505),

GSE57370 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE57370)

and GSE17342 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE17342)

were downloaded from the GEO database. GSE50505, which was based on

GPL17667 platform (Luminex Homo sapiens bead-based microRNA

profiling platform), was submitted by Liu et al. The dataset

contained 28 samples, including 20 Wilms tumor samples and 3 normal

kidney samples. GSE17342 was based on GPL8367 platform

(LC_MRA-1001_miRHuman_10.0_070802), including 2 Wilms tumor samples

and 2 normal kidney samples. GSE57370 was based on GPL16770

platform (Agilent-031181

Unrestricted_Human_miRNA_V16.0_Microarray), including 62 Wilms

tumor samples and 4 normal kidney samples.

Patients and tissue samples

Wilms tumor tissues and the corresponding adjacent

non-tumor tissues were obtained from 68 patients who had Wilms

tumors and had undergone surgery at the Women and Chidren's

Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou, China) between

July 2012 and July 2017. The age and sex distribution of WT

patients are shown in Table I.

Adjacent non-tumor tissues were obtained 3 cm away from the tumor,

and the lack of tumor cell infiltration was verified by

pathological examination. All tissue samples were frozen in liquid

nitrogen and stored at −80°C. All patients had not received

chemotherapy or radiotherapy before the surgery. Informed consent

was obtained from each patient, and the study protocol and consent

procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou

Medical University (Guangzhou, China).

| Table I.Relationship between miR-92a-3p and

the clinicopathological features of the Wilms tumor cases. |

Table I.

Relationship between miR-92a-3p and

the clinicopathological features of the Wilms tumor cases.

|

| miR-92a-3p

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristics | High (%) | Low (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

| 0.061 |

| Male | 38.2 | 16.2 |

|

|

Female | 30.9 | 14.7 |

|

| Age (years) |

|

| 0.832 |

|

<4 | 41.2 | 11.8 |

|

| ≥4 | 27.9 | 19.1 |

|

| Tumor size (cm) |

|

| 0.710 |

|

<10 | 51.5 | 16.2 |

|

| ≥10 | 17.6 | 14.7 |

|

| Histologic type |

|

| 0.353 |

|

Triphasic | 11.8 | 5.9 |

|

|

Blastemal | 13.2 | 4.4 |

|

|

Stromal | 17.6 | 8.8 |

|

|

Epithelial | 16.2 | 10.3 |

|

|

Others | 5.9 | 4.4 |

|

| Lung metastasis |

|

| 0.042 |

| No | 23.5 | 35.5 |

|

| Yes | 8.8 | 32.4 |

|

| Survival status |

|

| 0.016 |

|

Alive | 38.2 | 26.5 |

|

|

Deceased | 7.4 | 33.8 |

|

Primary cell line and culture

The fresh tumor tissues were sliced into 0.1

cm3 pieces and washed with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The

tissues were then incubated overnight with 2 U/ml dispase (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 4°C on a stirrer at 100 rpm,

followed by digestion with 160 µg/ml of collagenase A

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) at 37°C for 3 h.

Thecollected and digested cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) until the cells had grown in a

confluent monolayer at 37°C in a humidified chamber supplemented

with 5% CO2. A maintenance culture was carried out in a

25-ml flask with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 units/ml of

streptomycin and 100 µg/ml penicillin (both from Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The culture medium was replaced every 2

days and the cells were propagated every 3 days. For

cryopreservation, the cells were frozen in DMEM containing 10%

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 90%

FBS and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Transient transfection

The miR-92a-3p mimic, miR-92a-3p inhibitor and

corresponding negative control (miR-NC) were purchased from

Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The siRNA against

NOTCH1 (UGGCGGGAAGUGUGAAGCG) and its negative control were provided

by Takara Bio Inc. (Otsu, Japan). These molecular products were

transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for the various experiments according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the final concentration

of these products was 50 nM and the cells were harvested for

subsequent experiments at 24 h after transfection. Each experiment

was repeated three times each in triplicates.

RNA extraction and quantitative

real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the Wilms tumor tissues,

matched adjacent normal tissues and WT cells using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Briefly, all samples were treated with TRIzol followed by

chloroform. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at

4°C and 700 µl 75% ethanol was added to the aqueous layer. Finally,

the purified RNA was diluted with 30 µl of RNase-free water. cDNA

synthesis was performed with 2 µg total RNA using the PrimeScript™

RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) for

the next qPCR with Mir-X miRNA First-Strand Synthesis kit (Takara

Bio, Inc.) for microRNA according to the manufacturers'

instructions. The primers sequences of NOTCH1 were F,

TGCCAGACCAACATCAAC and R, CTCATAGTCCTCGGATTGC (Takara

Biotechnology, Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). The sequences of

miR-92a-3p were F: GGGGCAGTTATTGCACTTGTC and R:General reverse

primer for microRNA is purchased from RiboBio Co. Ltd. (Guangzhou,

China). The sequences of GAPDH were F: GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC and R:

TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA (Takara Biotechnology). A qPCR was performed

using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (Takara Bio) and the Applied

Biosystems 7500 Fluorescent Quantitative PCR system (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The mixtures were

incubated at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 amplification cycles

of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 34 sec. The comparative cycle

threshold method was used to quantify the relative expression

levels of mRNA and microRNA. Expression levels of the housekeeping

gene GAPDH and U6 were used to normalize the expression levels of

the genes-of-interest, respectively. The relative mRNA levels were

calculated based on the Ct values and normalized using the relative

housekeeping gene expression.

Cell proliferation assay

In vitro cell proliferation was measured

using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium

bromide (MTT) method following the manufacturer's instructions

(Nanjing KeyGen Biotech, Nanjing, China). Briefly, the transfected

cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2×103 cells/well)

and cultured for 5 days. The MTT solution (formazan in DMSO) was

added to each well at the indicated time-points (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5

days) and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The optical density value (OD)

of each well was measured at 450 nm using a microplate

spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT,

USA).

Cell colony formation assay

The transfected cells were seeded into 6-well plates

at a density of 100 cells/well. After culture for 10 days, the

colonies were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and

stained with 1% crystal violet. The colonies were imaged and

counted in five randomly selected fields under a light microscope

(Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Wound healing assay

Briefly, cells (1×105) were seeded in

6-well plates and incubated overnight. A wound was created with a

10-µm pipette tip and images were obtained under a light microscope

(Olympus Corp.). The wound gaps were measured per time-point.

Transwell assay

The assays were carried out in Transwell chambers

(8-µm pore size) (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA). Matrigel™

Matrix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was diluted 1:7 using

serum-free basal medium and 50 µl Matrigel Matrix dilution was

added to the upper chamber of the Transwell inserts. Moreover, 100

µl transfected cell (2×105/ml) suspensions were seeded

in the upper chambers precoated with Matrigel Matrix dilution in

24-well plates and cultured in serum-free basal medium. A total of

500 µl medium with 10% FBS was also added to the lower chambers.

After 24 h, cells in the upper chambers were removed using cotton

swabs. The inserts was washed three times with PBS, and cells that

invaded to the bottom surface of the insert were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde and stained using 1% crystal violet. The invading

cells were countedunder a Leica DMI4000B microscope (Leica

Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany) from randomly selected five

fields and photomicrographs were captured.

Luciferase reporter assay

The wild-type (WT) or mutant-type (MUT) seed region

at the 3′UTR of NOTCH1 was synthesized and cloned into the

downstream region of a firefly luciferase cassette in the

pGL3-promoter vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were

cotransfected with vectors carrying the WT 3′UTR or MUT 3′UTR

NOTCH1 and miR-92a-3p mimic or miR-NC by using Lipofectamine 2000

reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. After a 48-h

transfection, the cells were harvested to detect luciferase

activity by using the Dual-Luciferase assay (Promega

Corporation).

Western blotting assay

Total proteins were extracted from cells or tissues

with RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1%

SDS, 1% NP-40 and 1 mM MgCl) containing protease inhibitors. The

total protein concentration was determined using a BCA Protein

Assay kit (Nanjiing KeyGen Biotech). A total of 30 mg of protein

was separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then transferred

onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PDVF) membranes (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk and then incubated

with primary antibodies against NOTCH1 (rabbit IgG, 1:1,000; cat.

no. 3608S) and GAPDH (rabbit IgG, 1:1,000; cat. no. 5174) overnight

at 4°C. On the second day, the blots were washed with PBST and

incubated with secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, 1:2,000; cat.

no. 7074) for 2 h at room temperature. The antibodies were

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

The protein band was visualized by chemiluminescence imaging system

(ChemiDoc Touch; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). GAPDH

was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons, two-tailed Student's t-test,

Wilcoxon rank-test, Fisher's exact test, one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were performed.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated and multivariate Cox's

proportional harzards model was performed to determine the

independent factors. Survival curves were performed by

Kaplan-Meier's method and calculated by log-rank test. For

correlation, Spearman's and Pearson's correlation were used.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS,

Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with a two-sided significance level of

P<0.05.

Results

miR-92a-3p is downregulated in Wilms

tumors

To reveal the expression of miRNAs in Wilms tumor,

we downloaded the microarray chips concerning the miRNA gene

expression profiles of GSE50505, GSE57370 and GSE17342. We chose

the genes with P<0.05 and fold control (FC) 1.5 as criteria.

After analysis with InteractiVenn, we obtained a common gene

miR-92a-3p (Fig. 1A). To reveal the

role of miR-92a-3p in Wilms tumor, RT-qPCR was performed to examine

the expression levels of miR-92a-3p in tumor samples and adjacent

non-tumor tissues of 68 Wilms tumor patients. As revealed in

Fig. 1B, miR-92a-3p was frequently

downregulated in Wilms tumor, compared with that in the adjacent

tissues (P<0.001). To further investigate the clinical

significance of miR-92a-3p expression in Wilms tumor, we tested the

expression level of miR-92a-3p in patients with or without

metastasis and found that miR-92a-3p expression was lower in

patients with metastasis than patients without metastasis

(P<0.01) (Fig. 1C). We divided

the 68 patients into two groups according to the median value of

miR-92a-3p expression in the Wilms tumors: high miR-92a-3p

expression group and low miR-92a-3p expression group (Table I). In addition, Kaplan-Meier's

analysis (Fig. 1D) indicated that

Wilms tumor patients with low miR-92a-3p expression exhibited

poorer overall survival (P<0.05).

miR-92a-3p inhibits Wilms tumor cell

proliferation and colony formation

To examine the effect of miR-92a-3p on Wilms tumor

growth, we obtained the primary cells from a Wilms tumor (Fig. 2A). The Wilms tumor cells were then

transfected with the miR-92a-3p mimic, miR-NC and inhibitor.

miR-92a-3p expression was comfirmed by qPCR (Fig. 2B). The MTT assay (Fig. 2C) indicated that WT cells with

higher miR-92a-3p expression exhibited reduced proliferation

compared to the cells transfected with miR-NC. In contrast, the

Wilms tumor cells with low miR-92a-3p expression exhibited

increased proliferation (P<0.05). The colony formation assay

(Fig. 2D and E) demonstrated that

Wilms tumor cells transfected with the miR-92a-3p mimic developed

significantly lower rates of colony formation when compared with

the cells transfected with miR-NC. Additionaly, Wilms tumor cells

transfected with the miR-92a-3p inhibitor had a higher rate of

colony formation (P<0.05). These results suggest that miR-92a-3p

inhibitedthe proliferation and colony formation of Wilms tumor

cells.

miR-92a-3p inhibits Wilms tumor cell

migration and invasion

To measure the effect of miR-92a-3p on the migratory

and invasive capacities of the Wilms tumor cells, we used

Matrigel-coated Transwell experiments and wound healing assays. The

results revealed a significant decrease in the wound-healing

distance in the miR-92a-3p mimic-transfected WT cells after 24 h.

Meanwhile, the wound-healing distance of the miR-92a-3p

inhibitor-transfected Wilms tumor cells was more extensive when

compared with the miR-NC cells (Fig. 3A

and B). We observed that the miR-92a-3p mimic significantly

decreased the invasiveness of the Wilms tumor cells through

Matrigel. The miR-92a-3p inhibitor increased the invasion potential

of the Wilms tumor cells (Fig. 3C and

D). These results demonstrated that miR-92a-3p inhibits the

potential of Wilms tumor cells in terms of migration and

invasion.

NOTCH1 is a direct target of

miR-92a-3p in Wilms tumor

To explore the molecular mechanism by which

miR-92a-3p functions in Wilms tumor, we used bioinformatic

prediction software (TargetScan) to determine the potential target.

We identified that miR-92a-3p was able to bind the 3′-UTR of NOTCH1

(Fig. 4A). To further confirm this

binding, we performed a luciferase assay and demonstrated that

miR-92a-3p dramatically inhibited the luferase activity of the

wild-type (WT) 3′-UTR but not of the mutant-type (Mut) 3′-UTR and

blank vector of NOTCH1 (Fig. 4B).

Moreover, miR-92a-3p mimic significantly inhibited mRNA and protein

expression of NOTCH1 and the inhibitor promoted the NOTCH1

expression (Fig. 4C and D).

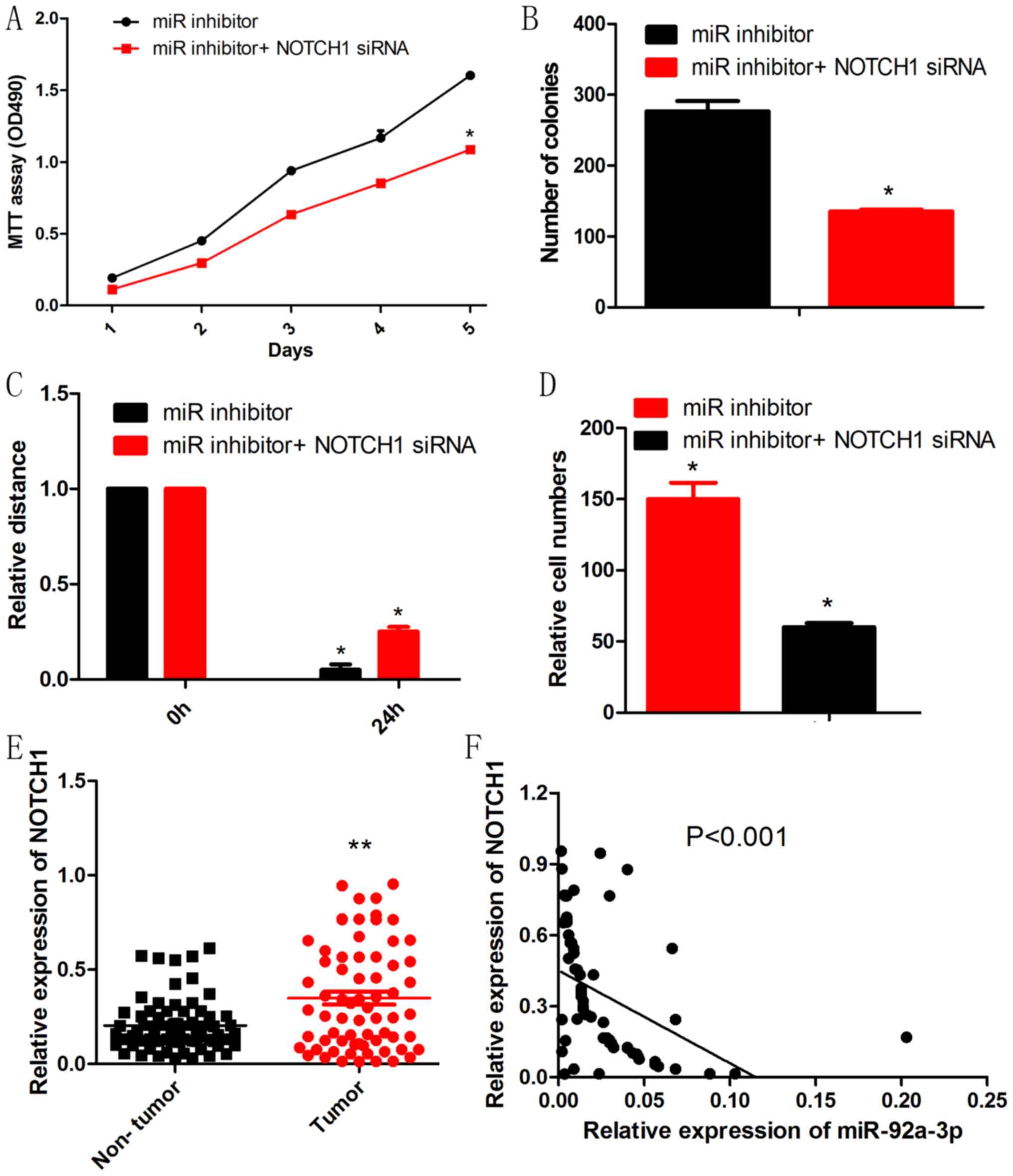

NOTCH1 knockdown rescued the effect of

miR-92a-3p inhibitor on Wilms tumor cells

To further determine whether NOTCH1 is a functional

target of miR-92a-3p in Wilms tumor, we performed a rescue

experiment. NOTCH1 siRNA reduced the promotive effects of the

miR-92a-3p inhibitor on proliferation, migration and invasion of

Wilms tumor cells (Fig. 5A-D). To

explore the relationship between miR-92a-3p and NOCTH1 in Wilms

tumortissues, RT-qPCR was performed to test the expression of

NOTCH1. As shown in Fig. 5E, Wilms

tumor tissues had significantly higher levels of NOTCH1 mRNA than

those of adjacent non-tumor tissues. Moreover, NOTCH1 mRNA had an

inverse correlation with miR-92a-3p expression in Wilms tumor

tissues (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

A series of microarray chips have been used to

detect the miRNA expression of Wilms tumors and these studies

reported the abnormal expression levels of various miRNAs in Wilms

tumor, such as the upregulated genes, miR-378 and miR-18b and the

downregulated genes, miR-193a-5p and miR-199a-5p (5,17).

However, studiesconcerning the cliniopathological and biological

mechanisms concerning miRNAs in Wilms tumors are sparse. In the

present study, we extracted the data from microarray profiles of

GSE50505, GSE57370 and GSE17342, including thousands of miRNA genes

in the human genome simultaneously, which has been widely used to

predict the potential therapeutic targets for tumors. Notably, we

identified a common downregulated gene miR-92a-3p in Wilms tumor.

The present study further confirmed the low expression of

miR-92a-3p in Wilms tumor and we also found that overexpression of

miR-92a-3p inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of

Wilms tumor cells. In addition, miR-92a-3p knockdown showed

contrary results. These results indicate that miR-92a-3p may serve

as a tumor suppressor.

NOTCH1 is a member of the Notch family, the

evolutionarily conserved family of transmembrane receptors, which

regulate cell fate, stem cell self-renewal and differentiation

during development (18,19). Recently, Notch1 was reported to take

part in diverse tumor processes including cell proliferation,

apoptosis, and cancer metastasis and angiogenesis in various types

of cancer (20,21). In addition, in kidney development,

Notch receptors were reported to regulate mesangial cell

specification, proliferation or survival (22). These results suggest that NOTCH

family receptors may play pivotal roles in Wilms tumor. In the

present study, we found that the expression of NOTCH1 was

downregulated by miR-92a-3p mimic, and NOTCH1 was upregulated by

the miR-92a-3p inhibitor. Moreover, the functions of miR-92a-3p

inhibitor on Wilms tumor were reversed by NOTCH1 knockdown. The

expression of NOTCH1 and miR-92a-3p had an obvious negative

correlation in Wilms tumor. The results above suggest that NOTCH1

is a direct target of miR-92a-3p and miR-92a-3p inhibits the

proliferation, migration and invasion of Wilms tumor by targeting

NOTCH1.

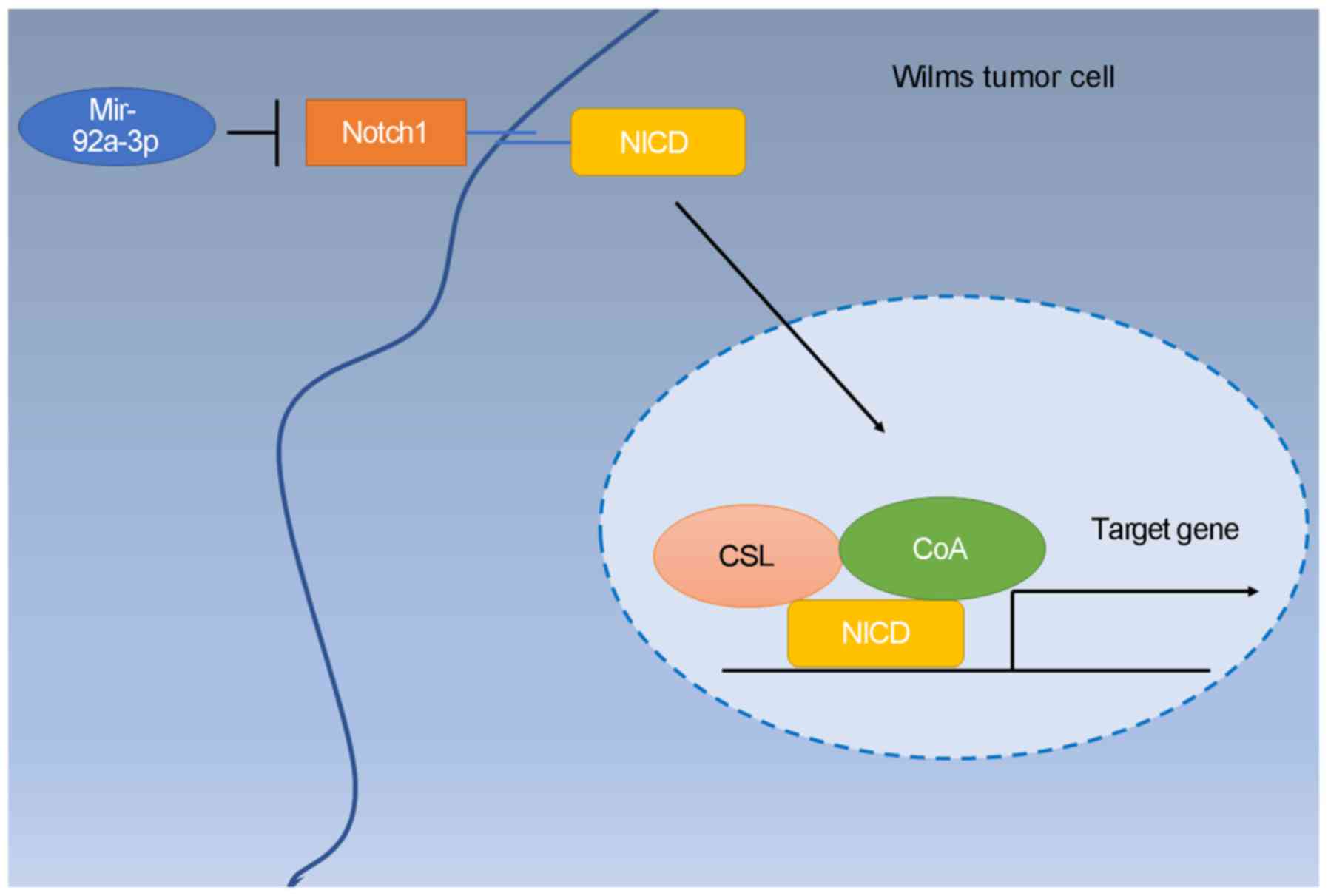

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

miR-92a-3p was downregulated inWilms tumor tissues and

significantly correlated with the lung metastasis of patients.

Furthermore, miR-92a-3p mimics suppressed Wilms tumor cell

proliferation, migration and invasion. Additionally, miR-92a-3p

knockdown promoted the progression. Moreover, NOTCH1 is a direct

target of miR-92a-3p and miR-92a-3p inhibits tumor progression by

targeting NOTCH1. Knockdown of NOTCH1 expression reversed the

promotive effect of the miR-92a-3p inhibitor on Wilms tumor

progression. In conclusion, miR-92a-3p blocks the progression of

Wilms tumor by targeting NOTCH1 (Fig.

6).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. zhongmin Li for his technical

support.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the

Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology

Foundation, P.R. China (no. 2016A020215009).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

GL and WJ designed the study; SZ wrote the

manuscript, collected clinical information and performed

statistical analyses; ZZ and WF assisted with PCR, western blotting

and in vitro experiments; LZ assisted with the

Dual-Luciferase reporter assays. All authors read and approved the

manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of

the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Informed consent was obtained from each patient, and

the study protocol and consent procedures were approved by the

Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou,

China).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Charlton J, Pavasovic V and

Pritchard-Jones K: Biomarkers to detect Wilms tumors in pediatric

patients: Where are we now? Future Oncol. 11:2221–2234. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cone EB, Dalton SS, Van Noord M, Tracy ET,

Rice HE and Routh JC: Biomarkers for wilms tumor: A systematic

review. J Urol. 196:1530–1535. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Qi C, Hu Y, Yang F, An H, Zhang J, Jin H

and Guo F: Preliminary observations regarding the expression of

collagen triple helix repeat-containing 1 is an independent

prognostic factor for Wilms' tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 51:1501–1506.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Brok J, Pritchard-Jones K, Geller JI and

Spreafico F: Review of phase I and II trials for Wilms' tumour e

Can we optimise the search for novel agents? Eur J Cancer.

79:205–213. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yu X, Li Z, Chan MT and Wu WK: The roles

of microRNAs in Wilms' tumors. Tumor Biol. 37:1445–1450. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Macfarlane LA and Murphy PR: MicroRNA:

Biogenesis, function and role in cancer. Curr Genomics. 11:537–561.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bushati N and Cohen SM: MicroRNA

functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 23:175–205. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Valinezhad Orang A, Safaralizadeh R and

Kazemzadeh-Bavili M: Mechanisms of miRNA-mediated gene regulation

from common down-regulation to mRNA-specifc upregulation. Int J

Genomics. 2014:9706072014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tie J and Fan D: Big roles of microRNAs in

tumorigenesis and tumor development. Histol Histopathol.

26:1353–1361. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hwang HW and Mendell JT: MicroRNAs in cell

proliferation, cell death, and tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer.

94:776–780. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Baltimore D, Boldin MP, O'Connell RM, Rao

DS and Taganov KD: MicroRNAs: New regulators of immune cell

development and function. Nat Immunol. 9:839–845. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang C, Wang C, Chen X, Yang C, Li K,

Wang J, Dai J, Hu Z, Zhou X, Chen L, et al: Expression profile of

microRNAs in serum: A fingerprint for esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Clin Chem. 56:1871–1879. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ma H, Pan JS, Jin LX, Wu J, Ren YD, Chen

P, Xiao C and Han J: MicroRNA-17-92 inhibits colorectal cancer

progression by targeting angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 376:293–302.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhou P, Ma L, Zhou J, Jiang M, Rao E, Zhao

Y and Guo F: miR-17-92 plays an oncogenic role and conveys

chemoresistance to cisplatin in human prostate cancer cells. Int J

Oncol. 48:1737–1748. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Song H, Zhang Y, Liu N, Zhao S, Kong Y and

Yuan L: miR-92a-3p exerts various effects in glioma and glioma

stem-Like cells specifically targeting CDH1/v-catenin and

Notch-1/Akt signaling pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 17:pii: E1799. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zheng G, Du L, Yang X, Zhang X, Wang L,

Yang Y, Li J and Wang C: Serum microRNA panel as biomarkers for

early diagnosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer.

111:1985–1992. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Watson JA, Bryan K, Williams R, Popov S,

Vujanic G, Coulomb A, Boccon-Gibod L, Graf N, Pritchard-Jones K and

O'Sullivan M: MiRNA profiles as a predictor of chemoresponsiveness

in Wilms' tumor blastema. PLoS One. 8:534172013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kopan R and Ilagan MX: The canonical Notch

signaling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell.

137:216–233. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fortini ME: Notch signaling: The core

pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 16:633–647.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bolos V, Grego-Bessa J and de la Pompa JL:

Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr Rev. 28:339–363.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu P, Qiu M, Zhang Z, Kang C, Jiang R, Jia

Z, Wang G, Jiang H and Pu P: The oncogenic roles of Notch1 in

astrocytic gliomas in vitro and in vivo. J Neurooncol. 97:41–51.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Boyle SC, Liu Z and Kopan R: Notch

signaling is required for the formation of mesangial cells from a

stromal mesenchyme precursor during kidney development.

Development. 141:345–354. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|