Introduction

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) form a

heterogenous population that consists of myeloid progenitor cells,

immature macrophages, immature granulocytes and immature dendritic

cells (DCs). The phenotype of MDSCs in mice is granulocyte receptor

1 (Gr-1)+CD11b+. In the steady state, MDSCs

have no inhibitory activity and are mostly present in the bone

marrow. The percentage of MDSCs is only 2–4% in the spleen, and

they are absent from the lymph nodes in mice. In tumor hosts, MDSCs

accumulate in lymphatic organs and tumor tissue, and they produce a

large amount of immune-inhibitory factors, including arginase I,

inducible nitric oxide synthase and reactive oxygen species, which

inhibit T-cell immune responses (1–3),

induce regulatory T-cell production, suppress natural killer (NK)

cell functions, and affect cytokine production and secretion by

macrophages. Furthermore, MDSCs can facilitate

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis and metastasis

(2,4–6).

The spleen is the largest immune organ, containing

nearly 25% of the body's immune cells. It has a vital role in the

immune response to tumors, and splenic NK cells and T cells exert

important anti-tumor functions (7–10).

However, the spleen is also a reservoir of precursor monocytes and

granulocytes, which may be mobilized to the tumor tissue and

differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and

neutrophils (TAN) that promote tumor progression. Splenectomy has

been indicated to markedly reduce TAM and TAN responses, thus

retarding tumor growth (11). A

previous study by our group identified an immune-suppressive status

in the spleen of a H22 orthotopic hepatoma mouse model. MDSCs were

the major inhibitory cells causing the immunosuppression in the

spleen (12). Similarly, Levy et

al (13) reported that the

spleen may be a reservoir of MDSCs and that splenectomy may reduce

the percentage of MDSCs in peripheral blood and tumor tissue.

To date, numerous studies have reported on the

mechanisms of MDSC accumulation in tumor tissue, and the factors

involved include chemokines, inflammatory factors,

colony-stimulating factor and complements (14–16).

Tumor-derived chemokines, including C-C motif chemokine ligand

(CCL)2, CCL5, CCL21 and C-X-C motif ligand (CXCL)8 were able to

recruit MDSCs to the tumor tissue, while blocking of these

chemokines or their receptors reduced the number of MDSCs at the

tumor sites and inhibited tumor growth (17–23).

The accumulation of MDSCs in the tumor may also be regulated by

inflammatory environmental factors, including interleukin (IL)-1β,

IL-6, prostaglandin E2, S100 calcium-binding protein A8/9 and tumor

necrosis factor (24–28).

By contrast, few studies have assessed MDSC

accumulation in the spleen under pathological conditions. In the

murine MCA203 fibrosarcoma model, nestin-positive splenocytes were

able to secrete CCL2 that attracted MDSCs to the spleen in a

CCR2-dependent manner (29). The

spleen is the primary site of immune responses, and its immune

status influences tumor growth. Therefore, it is important to

explore the mechanisms of MDSC localization and kinetics in the

spleen under pathological conditions. This may facilitate the

identification of novel factors and pathways involved in MDSC

accumulation in the spleen that may have a role in the contribution

of MDSCs to tumor progression. These factors and pathways may be

novel targets in immune therapy to block MDSCs in order to suppress

tumor growth.

In the present study, the mechanisms of MDSC

accumulation in the spleen of tumor-bearing (TB) mice were

explored. MDSC proliferation, apoptosis and the expression of

cytokines in the spleen were assessed. Chemokines upregulated in TB

mice were validated and their cellular origin was identified.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The H22 murine hepatoma cell line was purchased from

the China Center for Type Culture Collection (Wuhan, China). The

cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone; GE Healthcare,

Little Chalfont, UK) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum

(HyClone; GE Healthcare) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone;

GE Healthcare). The cells were grown at 37°C in an atmosphere

containing 5% CO2.

Mice

A total of 96 female BALB/c mice (age, 6–8 weeks;

weight, 20–25 g) were purchased from the animal center of Xi'an

Jiaotong University (Xi'an, China). The mice were housed under

specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility under a

12-h light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. All animal

procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals [National Institutes of Health (NIH);

publication from 1996] and were approved by the Xi'an Jiaotong

University Animal Care and Use Committee (Xi'an, China).

Orthotopic mouse model of

hepatocellular carcinoma

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with

106 H22 cells (at the concentration of 107

cells/ml in saline). After 12 days, ascites fluid containing

floating tumor cells was collected from these mice, which was

centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C to retrieve the cells,

which were washed twice with saline. These cells were subsequently

injected under the capsule of the left liver lobe of each mouse (2

×105 tumor cells at the concentration of 107

cells/ml). Four days later, white tumor nodules had formed on the

liver, indicating the successful generation of the H22 hepatoma

model.

Generation of single-cell suspensions

of splenocytes

Mice were sacrificed and the spleens were collected

at one, two and three weeks after tumor inoculation. Spleens were

dissociated into single-cell suspensions with the gentleMACS

Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) in the

buffer [0.01 mol/l PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Amresco, Solon,

OH, USA) and 2 mmol/l EDTA], using the C tube and the ‘m_spleen_01’

program according to the manufacturer's protocols. Subsequently,

the cell suspensions were centrifuged at 300 × g for 30 sec at room

temperature. Next, the splenocytes suspensions were strained

through a 70-µm mesh to remove clumps and generate single-cell

suspensions.

Flow cytometric analysis

The ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (0.15

mol/l NH4Cl, 1 mmol/l KHCO3 and 0.1 mmol/l

EDTA, pH 7.2) was added to the splenocytes to remove red blood

cells. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with PBS. Cells

(106) were incubated with anti-CD16/CD32 (cat. no.

101302; 10 µg/ml; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 10 min at 4°C

to prevent non-specific labeling of surface receptors. Next, cells

were incubated with monoclonal antibodies, including anti-mouse

granulocyte receptor 1 (Gr-1)-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)

(cat. no. 108405), anti-mouse Ly6G-FITC (cat. no. 127605),

anti-mouse Ly6C-phycoerythrin (PE) (cat. no. 128007), anti-mouse

CD11b-allophycocyanine (APC)-(cyanine)Cy7 (cat. no. 101226),

anti-mouse C-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CCR1)-APC (cat. no.

152503) (all from BioLegend; 2.5 µg/ml dilution), anti-mouse

CD11b-PE (cat. no. 12-0112; 0.6 µg/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, CA,

USA), anti-mouse Fas-APC (cat. no. 17-0951; 10 µg/ml; eBioscience)

and their corresponding isotype antibodies, including FITC rat

immunoglobulin (Ig)G2b, κ (cat. no. 400605); FITC rat IgG2a, κ

(cat. no. 400505); PE rat IgG2c, κ (cat. no. 400707); APC/Cy7 rat

IgG2b, κ (cat. no. 400623); APC rat IgG2b, κ (cat. no. 400611) (all

from BioLegend; 2.5 µg/ml dilution); PE rat IgG2b, κ (cat. no.

12-4031; 0.6 µg/ml); APC mouse IgG1, κ (cat. no. 17-4714; 10 µg/ml)

(both from eBioscience) as the control for 30 min at 4°C in the

dark. Following washing, the cells were analyzed using a FACSCanto

instrument with FACSDiva 7.0 software (BD Biosciences, Franklin

Lakes, NJ, USA).

To assess splenic MDSC proliferation, splenic cell

suspensions were stained with anti-mouse Gr-1-FITC and anti-mouse

CD11b-PE antibodies for 30 min at 4°C, followed by incubation with

cold 70% ethanol (precooled to −20°C; added in a drop-wise manner

to the cells while vortexing) at −20°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the

cells were washed three times, stained with anti-mouse Ki-67-APC

antibody (cat. no. 652405; 2.5 µg/ml; BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C

in the dark, washed and analysed with a flow cytometer.

To assess splenic MDSC apoptosis, splenic cell

suspensions were stained with anti-mouse Gr-1-FITC and anti-mouse

CD11b-PE, followed by Annexin V-APC (cat. no. 640920; BioLegend)

and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; cat. no. 420403; 2.5 µg/ml;

BioLegend). In brief, 106 cells were washed twice and

re-suspended in Annexin V binding buffer (cat. no. 422201;

BioLegend). Next, 5 µl Annexin V-APC and 5 µl 7-AAD were added to

the cells. Cells were incubated for 15 min at 4°C in the dark,

re-suspended in 400 µl binding buffer and analyzed using a

FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) within 1 h.

Fluorescence-activated sorting of

splenic macrophages

To isolate splenic macrophages, single-cell

suspensions of splenocytes were first incubated with anti-mouse

CD16/32 antibody (cat. no. 101302; 10 µg/ml; BioLegend) for 10 min

at 4°C to prevent non-specific labeling of surface receptors,

followed by incubation with monoclonal antibodies, including

anti-mouse F4/80-PE and (cat. no. 123109; 10 µg/ml; BioLegend)

anti-mouse CD11b-APC-Cy7 (cat. no. 101226; 2.5 µg/ml; BioLegend),

for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Cells were washed twice and

F4/80+CD11b+ double-positive cells were

isolated with a FACSAria II instrument (BD Biosciences). The purity

of the sorted macrophages was verified by flow cytometry (FACSAria

II; BD Biosciences).

Cytokine array

The concentrations of cytokines in the spleens of

normal and TB mice were quantified using the Mouse Cytokine Array

G3 (cat. no. AAM-CYT-G3-4; RayBiotech, Norcross, GA, USA) according

to the manufacturer's protocols. After all of the procedure steps,

the chip was scanned with an Axon GenePix scanner (GenePix 4000B;

Axon Instruments, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Protein array data were

annotated and processed with GenePix Pro 6.0 software (Molecular

Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The expression levels

(fluorescent signal intensities) of each cytokine were calculated

by subtracting the mean absorbance of the blank sample, with

normalization to a positive control.

ELISA

The levels of murine CCL9 and CXCL2 in the spleens

of normal and TB mice were measured using ELISA kits (cat. nos.

F111602 and F1117; Westang, Shanghai, China). Assays were performed

in duplicate according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

For analysis of CCL9 gene expression, total RNA was

extracted from the isolated splenic macrophages using TRIzol

reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary (c)DNA

was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with a

genomic DNA eraser (cat. no. RR047A, Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu,

Japan). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR® Premix

Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) kit (cat. no. RR820A, Takara Bio,

Inc.) in a 20-µl reaction system, including 10 µl Premix Ex Taq II

(Takara Bio, Inc.), 0.4 µl 5-carboxy rhodamine X reference dye II

(Takara Bio, Inc.), 0.8 µl of 0.4 µM forward primer and 0.8 µl of

0.4 µM reverse primer, 2 µl cDNA (resembling the transcription

product of 50 ng RNA) and 6 µl distilled water. The following

primers were used: CCL9 FP, 5′-CCCTCTCCTTCCTCATTCTTACA-3′ and RP,

5′-AGTCTTGAAAGCCCATGTGAAA-3′; GAPDH FP, 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′

and RP, 5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′. Amplifications of CCL9 and

GAPDH transcripts were performed during 40 PCR cycles using the ABI

7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The initial denaturation step was at 95°C for 30

sec. Each PCR amplification cycle included a denaturation step at

95°C for 5 sec, and a primer annealing and elongation step at 60°C

for 30 sec. The expression levels were calculated as the relative

cDNA content normalized to GAPDH expression (2−ΔΔCq

method) (30). Three independent

replicates were performed.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. Data were analyzed with Prism 5 software (GraphPad

Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Student's t-test was used to

compare the difference between the two groups. For more than two

groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test was performed.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

H22 tumor induces accumulation of

MDSCs in the spleen

The murine H22 orthotopic HCC model was established

and it was determined whether the development of H22 tumors was

associated with an increased number of MDSCs in the spleen. The

percentage of splenic MDSCs increased significantly in TB mice

compared with that in normal mice at week 1 (6.82±2.92 vs.

3.44±0.60%, P<0.05), week 2 (43.20±11.03 vs. 4.90±0.90%,

P<0.001) and week 3 (13.28±4.66 vs. 3.42±0.48%, P<0.001)

post-tumor inoculation, with the greatest difference observed at

week 2 (Fig. 1). These results

suggest that a H22 tumor may induce the accumulation of

CD11b+Gr-1+ cells in the spleen in

vivo.

| Figure 1.MDSCs accumulate in the spleen during

tumor growth. Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were prepared

and stained with anti-mouse-Gr-1 monoclonal antibody conjugated

with FITC and anti-mouse CD11b monoclonal antibody conjugated with

PE, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative

fluorescence-assisted cell sorting plots of splenocyte

preparations. A live gate P1 was set in the FSC/SSC plot.

Subsequently, the populations of CD11b-PE and Gr-1-FITC cells were

displayed in dot plots. (B) The percentage of splenic MDSCs

(Gr-1+CD11b+, gate P2 within live gate) in

H22 hepatoma mice (▲) and normal mice (■) at weeks 1, 2 and 3

post-tumor inoculation (n=6); Values are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 compared with

normal mice. TB, tumor-bearing; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor

cells; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin; SSC,

side scatter; FSC, forward scatter; Gr-1, granulocyte receptor

1. |

Accumulation of MDSCs in the spleen is

not associated with their proliferation and apoptosis

It was investigated whether the accumulation of

splenic MDSCs in TB mice resulted from their increased

proliferation and/or reduced apoptosis. First the proliferation

status of splenic MDSCs was assessed by staining for Ki-67, a

marker of cell proliferation. The percentage of Ki-67+

splenic MDSCs was not significantly different between TB mice and

normal mice at any of the time-points. The mean fluorescent

intensity (MFI) of Ki-67 in splenic MDSCs was also not

significantly different between TB mice and normal mice (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Accumulation of splenic MDSCs in H22

hepatoma mice is not associated with their proliferative status.

Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were stained with anti-mouse

Gr-1 monoclonal antibody conjugated with FITC and anti-mouse CD11b

monoclonal antibody conjugated with PE, followed by

permeabilization with 70% ethanol and staining with anti-mouse

Ki-67 antibody conjugated with APC. (A) Representative flow

cytometry plots and gating strategy. A live gate P1 was set in the

FSC/SSC plot and CD11b+/Gr-1+ were included

in the further analysis with gate P2. Subsequently, the selected

cells were displayed in a histogram for Ki-67-APC. (B) The

percentage of Ki-67+ MDSCs (left panel) and the MFI of

Ki-67 in MDSCs (right panel) in H22 hepatoma and normal mice (n=6).

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. TB,

tumor-bearing; APC, allophycocyanine; MDSCs, myeloid-derived

suppressor cells; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE,

phycoerythrin; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter; Gr-1,

granulocyte receptor 1; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity. |

Next, the apoptosis of splenic MDSCs was assessed.

No difference in the amount of total (AnnexinV+)

apoptotic MDSCs was identified between TB and normal mice at weeks

1, 2 and 3 post-tumor inoculation (Fig.

3). Fas protein is an apoptotic protein expressed on the cell

surface, and therefore, Fas expression on the splenic MDSCs was

also assessed. Neither the percentage of Fas+ splenic

MDSCs nor the MFI of Fas in splenic MDSCs was different between TB

mice and normal mice at any of the time-points assessed (Fig. 4).

| Figure 3.Accumulation of splenic MDSCs in H22

hepatoma mice is not caused by alterations in their apoptotic rate.

Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were stained with anti-mouse

Gr-1 monoclonal antibody conjugated with FITC and anti-mouse CD11b

monoclonal antibody conjugated with PE, followed by staining with

anti-mouse AnnexinV antibody conjugated with APC and viability dye

7-AAD. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots and gating strategy.

A live gate P1 was set in the FSC/SSC plot and

CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells were included in the

further analysis with gate P2. Subsequently, the selected cells

were displayed in histograms for Annexin-APC or 7-AAD. Annexin

V+/7-AAD− indicates cells in early apoptosis

and Annexin V+/7-AAD+ indicates cells in late

apoptosis. (B) Total apoptotic MDSC populations

(AnnexinV+) in TB and normal mice are presented. Values

are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). TB,

tumor-bearing; APC, allophycocyanine; MDSCs, myeloid-derived

suppressor cells; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE,

phycoerythrin; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter; Gr-1,

granulocyte receptor 1; 7-AAD, 7-amino actinomycin D; PerCP,

peridinin chlorphyll protein; Cy, cyanine. |

| Figure 4.Mice with hepatoma and normal mice do

not exhibit any difference in the expression of apoptotic protein

Fas in splenic MDSCs. Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were

stained with anti-mouse Gr-1 antibody conjugated with FITC,

anti-mouse CD11b antibody conjugated with PE and anti-mouse Fas

antibody conjugated with APC. (A) Representative flow cytometry

plots and gating strategy. A live gate P1 was set in the FSC/SSC

plot and CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells were included in

a further analysis with gate P2. Subsequently, the selected cells

were displayed in a histogram for Fas-APC. (B) The percentage of

Fas+ MDSCs (left panel) and the MFI of Fas in MDSCs

(right panel) in H22 hepatoma and normal mice. Values are expressed

as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). TB, tumor-bearing; APC,

allophycocyanine; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; FITC,

fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin; SSC, side scatter;

FSC, forward scatter; Gr-1, granulocyte receptor 1; MFI, mean

fluorescent intensity. |

These results indicate that the accumulation of

MDSCs in the spleen was not associated with their proliferation or

apoptosis.

Accumulation of splenic MDSCs in TB

mice is associated with increases in the level of splenic CCL9

The accumulation of splenic MDSCs in TB mice may be

caused by their chemotaxis to the spleen (29). To identify the factors involved, a

protein chip assay was then performed for the simultaneous

detection of 62 cytokines in the spleen of TB and untreated mice at

weeks 1, 2 and 3 post-tumor inoculation (Fig. 5A). At certain time-points, the

fluorescent signals of 11 cytokines were higher and those of 8

cytokines were lower in TB mice compared with those in untreated

mice. Among the upregulated cytokines, there were 7 chemokines:

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 13 (CXCL13), CXCL16, chemokine (C-C

motif) ligand 5 (CCL5), CCL12, CCL9, CXCL2 and CXCL4 (Fig. 5B). However, two of them, CXCL16 and

CCL12, were only expressed at low levels and one of them, CXCL13,

also known as B lymphocyte chemoattractant, is a chemotactic factor

for B lymphocytes. Another chemokine, CCL5, is a chemotactic factor

for T cells, eosinophils and basophils. CXCL4 has been reported to

negatively control the amount of MDSCs (31), as well as to inhibit angiogenesis

and tumor growth (32,33). Therefore, its elevated expression

was not correlated with the accumulation of MDSCs (Table I). Subsequently, the role of CCL9

and CXCL2 in MDSC accumulation in the spleen of TB mice was further

investigated.

| Figure 5.Differential expression of 62

cytokines in the spleen of H22 hepatoma and normal mice. A

RayBiotech mouse cytokine antibody array was used to compare the

expression of 62 cytokines in the splenic tissues of untreated and

TB mice. (A) Mouse cytokine antibody array membranes. (B)

Quantification of A. The upregulated (upper part) and downregulated

(lower part) cytokines in the spleen of TB mice compared with

untreated mice. Among the upregulated cytokines, seven chemokines

are indicated by rectangles. TB, tumor-bearing; 1w, 1 week; G-CSF,

granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; IGFBP3, insulin-like growth

factor-binding protein 3; CCL12, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 12;

CXCL2, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2; sTNFR, soluble tumor

necrosis factor receptors; TIMP1, tissue inhibitors of

metalloproteinase 1; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; XCL1,

chemokine (C motif) ligand. |

| Table I.Upregulated chemokines in spleen of

H22 hepatoma mice. A total of 62 cytokines were detected in spleen

tissue of untreated and TB mice at weeks 1, 2 and 3 post-tumor

inoculation using a mouse cytokine antibody array. |

Table I.

Upregulated chemokines in spleen of

H22 hepatoma mice. A total of 62 cytokines were detected in spleen

tissue of untreated and TB mice at weeks 1, 2 and 3 post-tumor

inoculation using a mouse cytokine antibody array.

|

| Fluorescent signal

intensity (normalized to positive control) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Abbreviation | Untreated | TB-1w | TB-2w | TB-3w | Chemotactic

cells |

|---|

| CXCL13 | 374 | 282 | 270 | 563 | B |

| CXCL16 | 155 | 184 | 171 | 206 | T, NKT |

| CCL5 | 916 | 1132 | 729 | 91 | T, eosinophils,

basophils |

| CCL12 | 42 | 53 | 18 | 184 | Eosinophils,

monocytes, lymphocytes |

| CCL9 | 3298 | 4770 | 5644 | 7677 | DC |

| CXCL2 | 955 | 502 | 1343 | 926 | Polymorphonuclear

leukocytes |

| CXCL4 | 3907 | 256 | 9609 | 4638 | Neutrophils,

monocytes, fibroblasts |

The expression of CCL9 was significantly higher in

the spleen of TB mice compared with that in untreated mice at week

2 post-tumor inoculation (Fig. 6A),

while there was no significant difference in the expression of

CXCL2 at any of the time-points assessed (Fig. 6B). Next, it was determined whether

splenic MDSCs expressed CCR1, the receptor for CCL9. It was

revealed that splenic MDSCs isolated from TB mice and normal mice

expressed CCR1. Furthermore, granulocyte-like MDSCs (G-MDSCs,

CD11b+ly6G+ly6Clow) and

monocyte-like MDSCs (MO-MDSCs,

CD11b+ly6G−ly6Chi) expressed CCR1

(Fig. 7A), suggesting that the

increased expression of CCL9 in the spleen of TB mice may attract

MDSCs in a CCR1-dependent manner. Of note, the expression of CCR1

on MO-MDSCs in TB mice was higher compared with that in normal

mice, while such a difference was not observed for G-MDSCs

(Fig. 7B).

| Figure 7.Splenic MDSCs express CCR1, the

receptor for chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9. Splenic single-cell

suspensions were stained with anti-mouse ly6G monoclonal antibody

conjugated with FITC, anti-mouse ly6C monoclonal antibody

conjugated with PE, anti-mouse CD11b monoclonal antibody conjugated

with APC-Cy7 and anti-mouse CCR1 monoclonal antibody conjugated

with APC. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots and gating

strategy. Left panel: A live gate P1 was set in the FSC/SSC plot

and CD11b+ cells were included in further analysis with

gate P2 (APC/Cy7 rat immunoglobulin G2b, κ isotype antibody was

used as the negative control for the separation of negative and

positive cell populations). Subsequently, the selected cells were

displayed in a histogram for ly6C-PE and ly6G-FITC. The population

of CD11b+ly6G+ly6Clow cells refers

to G-MDSCs, and the population of

CD11b+ly6G−ly6Chigh cells refers

to MO-MDSCs. Right panel: Representative plots for the expression

of CCR1 on G-MDSCs and MO-MDSCs from the spleen of normal and TB

mice. (B) The MFI of CCR1 on G-MDSCs (left panel) and MO-MDSCs

(right panel) from H22 hepatoma and normal mice (n=6). Values are

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. TB, tumor-bearing; G-MDSCs, granulocytic

myeloid-derived suppressor cells; MO-MDSCs, monocytic MDSCs; TB,

tumor-bearing; APC, allophycocyanine; FITC, fluorescein

isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward

scatter; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; CCR1, C-C motif chemokine

receptor 1; Cy, cyanine. |

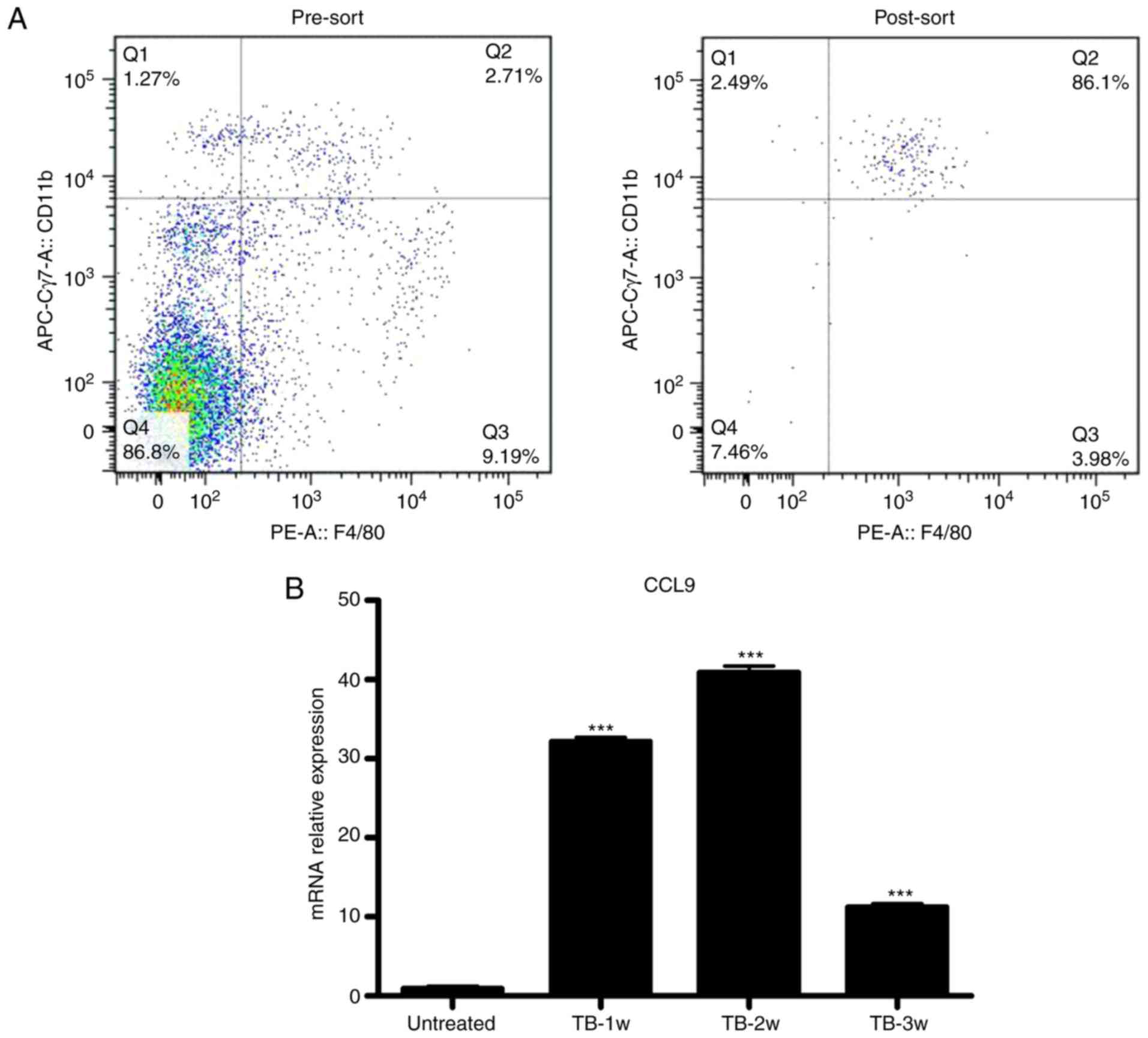

Splenic macrophages produce elevated

levels of CCL9 in tumor-bearing mice

Next, it was determined which splenic cells secrete

CCL9. CCL9 may be secreted by mononuclear phagocytic cells

(34). It was examined whether

macrophages were the source of CCL9 in spleen of TB mice. Splenic

macrophages (CD11b+/F4/80+) from untreated

and TB mice were isolated by fluorescence-assisted cell sorting

(Fig. 8A) and the expression levels

of CCL9 were detected by RT-qPCR. Splenic macrophages from TB mice

produced higher levels of CCL9 than control macrophages at weeks 1,

2 and 3 (Fig. 8B). These results

suggest that macrophages may be the source of CCL9 the in the

spleen of H22 hepatoma mice.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported that the frequencies

of MDSCs increased not only in tumor tissue but also in the spleen

of TB mice (12,24,35).

The accumulation of splenic MDSCs in TB mice may be caused by their

increased proliferation, decreased apoptosis or enhanced chemotaxis

to the spleen. In the present study, all three aspects were

investigated.

It remains elusive whether the proliferation of

MDSCs occurs mainly in the bone marrow or in the spleen. The spleen

is the major site of MDSC proliferation in the 4T1 mammary cancer

model, and the expansion of splenic MDSCs was caused by their

increased survival and decreased apoptosis (36). By contrast, in murine 3LL lung

cancer, B16 melanomas and Meth A fibrosarcomas, the proliferation

of MDSCs primarily occurs in the bone marrow and not in the

peripheral blood, the spleen or the tumor tissue (37). Therefore, in the murine H22

orthotopic hepatoma model of the present study, changes in splenic

MDSC proliferation and apoptosis were first assessed. It was

identified that the expansion of splenic MDSCs was not associated

with their proliferation or apoptosis.

Next, the mechanisms of MDSCs recruitment to the

spleen were assessed. In the murine MCA203 fibrosarcoma model,

nestin-positive splenocytes are able to secrete CCL2, which caused

an elevated level of CCL2 in the spleen and induced MDSC

accumulation in the spleen via CCR2 (29). In the present H22 hepatoma model, it

was investigated which factor is able to attract MDSCs to the

spleen by screening for 62 cytokines. The cytokine protein array

and ELISA results revealed that the CCL9 chemokine was highly

expressed in the spleen of TB mice.

The overexpressed CCL9 exerts its chemotactic

function through binding to its receptor CCR1. Therefore, it was

next determined whether MDSCs expressed CCR1. The splenic MDSCs

(including G-MDSCs and MO-MDSCs) from normal and TB mice were

identified to express CCR1. This indicates that the recruitment of

MDSCs to the spleen of TB mice was driven by increases of CCL9 as

well as its receptor CCR1, leading to the accumulation of MDSCs in

the spleen.

It was then investigated which cell type in the

spleen secretes CCL9 in TB mice. CCL9 may be secreted by

macrophages, DCs, Langerhans cells, gliocytes, osteoclasts and

certain types of tumor cell, including intestinal cancer cells.

MDSCs may also be a source of CCL9 (38–40).

As the percentage of macrophages in the spleen is higher than that

of DCs (35,41,42),

the expression of CCL9 in macrophages was examined and it was

revealed that splenic macrophages from TB mice had significantly

elevated levels of CCL9 compared with those in normal mice.

Therefore, it was concluded that the elevated CCL9 secreted by

splenic macrophages attracted MDSCs to the spleen of TB mice.

In the H22 orthotopic hepatoma model, a reduction in

spleen weight from week 2 to week 3 was previously observed

(12). The total number of

splenocytes, including macrophages, may decrease at week 3.

Macrophages viability and activity may decrease, resulting in

reduced cytokine secretion (43).

This may explain for the lower expression of CCL9 in the spleen and

reduced recruitment of MDSCs to the spleen at week 3 compared with

that at week 2.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

suggest that in the H22 hepatoma model, splenic macrophages

secreted CCL9 that induced MDSC accumulation in the spleen in a

CCR1-dependent manner. Further studies should assess which other

splenocytes, including DCs or MDSCs, secrete CCL9, whether the

mobilization of MDSCs to the spleen may be inhibited by targeting

CCL9 or CCR1, and how such an inhibition may affect tumor

growth.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Malgorzata

A. Garstka (Core Research Lab of the Second Affiliated Hospital of

Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China) for critical reading of

the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Program for

Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Teams at University

(grant no. 1171), the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant no. 81001309) and the Key Research and Development Program

of Shaanxi Province of China (grant no. 2017ZDCXL-SF-02-05,

2018SF-197).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed during this study

are included in this manuscript.

Authors' contributions

BL performed the experiments and wrote the first

draft of the manuscript. NH, HC and PW assisted in the

establishment of the tumor model and the sample preparation of flow

cytometry. SZ assisted in the statistical analysis and data

interpretation. JY and ZL designed the study and supervised the

experimental work. All authors reviewed the manuscript prior to its

submission and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal procedures complied with the Guide for

the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication, 1996) and

were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Xi'an

Jiaotong University (Xi'an, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Talmadge JE and Gabrilovich DI: History of

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 13:739–752. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Schrader J: The role of MDSCs in

hepatocellular carcinoma-in vivo veritas? J Hepatol. 59:921–923.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E and

Gabrilovich DI: The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in

the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 37:208–220. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Arina A and Bronte V: Myeloid-derived

suppressor cell impact on endogenous and adoptively transferred T

cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 33:120–125. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pan PY, Ma G, Weber KJ, Ozao-Choy J, Wang

G, Yin B, Divino CM and Chen SH: Immune stimulatory receptor CD40

is required for T-cell suppression and T regulatory cell activation

mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cancer Res.

70:99–108. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gabrilovich DI: Myeloid-derived suppressor

cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 5:3–8. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pardoll DM: Distinct mechanisms of tumor

resistance to NK killing: Of mice and men. Immunity. 42:605–606.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

You TG, Wang HS, Yang JH, Qian QJ, Fan RF

and Wu MC: Transfection of IL-2 and/or IL-12 genes into spleen in

treatment of rat liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 10:2190–2194.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Imai S, Nio Y, Shiraishi T, Tsubono M,

Morimoto H, Tseng CC, Kawabata K, Masai Y and Tobe T: Effects of

splenectomy on pulmonary metastasis and growth of SC42 carcinoma

transplanted into mouse liver. J Surg Oncol. 47:178–187. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zusman I, Kossoy G and Ben-Hur H: T cell

kinetics and apoptosis in immune organs and mammary tumors of rats

treated with cyclophosphamide and soluble tumor-associated

antigens. In Vivo. 16:567–576. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A,

Rauch PJ, Chudnovskiy A, Berger C, Ryan RJ, Iwamoto Y, Marinelli B,

Gorbatov R, et al: Origins of tumor-associated macrophages and

neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:2491–2496. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li B, Zhang S, Huang N, Chen H, Wang P, Li

J, Pu Y, Yang J and Li Z: Dynamics of the spleen and its

significance in a murine H22 orthotopic hepatoma model. Exp Biol

Med. 241:863–872. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Levy L, Mishalian I, Bayuch R, Zolotarov

L, Michaeli J and Fridlender ZG: Splenectomy inhibits non-small

cell lung cancer growth by modulating anti-tumor adaptive and

innate immune response. Oncoimmunology. 4:e9984692015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G,

Bronte V and Borrello I: High-dose granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune

response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells.

Cancer Res. 64:6337–6343. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Waight JD, Hu Q, Miller A, Liu S and

Abrams SI: Tumor-derived G-CSF facilitates neoplastic growth

through a granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell-dependent

mechanism. PLoS One. 6:e276902011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Markiewski MM, DeAngelis RA, Benencia F,

Ricklin-Lichtsteiner SK, Koutoulaki A, Gerard C, Coukos G and

Lambris JD: Modulation of the antitumor immune response by

complement. Nat Immunol. 9:1225–1235. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shields JD, Kourtis IC, Tomei AA, Roberts

JM and Swartz MA: Induction of lymphoidlike stroma and immune

escape by tumors that express the chemokine CCL21. Science.

328:749–752. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yu F, Shi Y, Wang J, Li J, Fan D and Ai W:

Deficiency of Kruppel-like factor KLF4 in mammary tumor cells

inhibits tumor growth and pulmonary metastasis and is accompanied

by compromised recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Int

J Cancer. 133:2872–2883. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhou Y and Guo F: A selective

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 agonist SEW-2871 aggravates

gastric cancer by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J

Biochem. 163:77–83. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chang AL, Miska J, Wainwright DA, Dey M,

Rivetta CV, Yu D, Kanojia D, Pituch KC, Qiao J, Pytel P, et al:

CCL2 produced by the glioma microenvironment is essential for the

recruitment of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor

cells. Cancer Res. 76:5671–5682. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Blattner C, Fleming V, Weber R, Himmelhan

B, Altevogt P, Gebhardt C, Schulze TJ, Razon H, Hawila E, Wildbaum

G, et al: CCR5+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells are

enriched and activated in melanoma lesions. Cancer Res. 78:157–167.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yamamoto T, Kawada K, Itatani Y, Inamoto

S, Okamura R, Iwamoto M, Miyamoto E, Chen-Yoshikawa TF, Hirai H,

Hasegawa S, et al: Loss of SMAD4 promotes lung metastasis of

colorectal cancer by accumulation of CCR1+

tumor-associated neutrophils through CCL15-CCR1 axis. Clin Cancer

Res. 23:833–844. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Long X, Ye Y, Zhang L, Liu P, Yu W, Wei F,

Ren X and Yu J: I L-8, a novel messenger to cross-link inflammation

and tumor EMT via autocrine and paracrine pathways (Review). Int J

Oncol. 48:5–12. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kapanadze T, Gamrekelashvili J, Ma C, Chan

C, Zhao F, Hewitt S, Zender L, Kapoor V, Felsher DW, Manns MP, et

al: Regulation of accumulation and function of myeloid derived

suppressor cells in different murine models of hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatol. 59:1007–1013. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bunt SK, Yang L, Sinha P, Clements VK,

Leips J and Ostrand-Rosenberg S: Reduced inflammation in the tumor

microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived

suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res.

67:10019–10026. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sinha P, Clements VK, Fulton AM and

Ostrand-Rosenberg S: Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by

inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res.

67:4507–4513. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Eisenblaetter M, Flores-Borja F, Lee JJ,

Wefers C, Smith H, Hueting R, Cooper MS, Blower PJ, Patel D,

Rodriguez-Justo M, et al: Visualization of tumor-immune

interaction-target-specific imaging of S100A8/A9 reveals

pre-metastatic niche establishment. Theranostics. 7:2392–2401.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ba H, Li B, Li X, Li C, Feng A, Zhu Y,

Wang J, Li Z and Yin B: Transmembrane tumor necrosis factor-α

promotes the recruitment of MDSCs to tumor tissue by upregulating

CXCR4 expression via TNFR2. Int Immunopharmacol. 44:143–152. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ugel S, Peranzoni E, Desantis G, Chioda M,

Walter S, Weinschenk T, Ochando JC, Cabrelle A, Mandruzzato S and

Bronte V: Immune tolerance to tumor antigens occurs in a

specialized environment of the spleen. Cell Rep. 2:628–639. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ: Analyzing

real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc.

3:1101–1108. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu P, He H, Gu Y, Wang Y, Sun Z, Yang L

and Miao C: Surgical trauma contributes to progression of colon

cancer by downregulating CXCL4 and recruiting MDSCs. Exp Cell Res.

370:692–698. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vandercappellen J, Van Damme J and Struyf

S: The role of the CXC chemokines platelet factor-4 (CXCL4/PF-4)

and its variant (CXCL4L1/PF-4var) in inflammation, angiogenesis and

cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 22:1–18. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang Z and Huang H: Platelet factor-4

(CXCL4/PF-4): An angiostatic chemokine for cancer therapy. Cancer

Lett. 331:147–153. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Youn BS, Jang IK, Broxmeyer HE, Cooper S,

Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Elick TA, Fraser MJ Jr and

Kwon BS: A novel chemokine, macrophage inflammatory protein-related

protein-2, inhibits colony formation of bone marrow myeloid

progenitors. J Immunol. 155:2661–2667. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, Combs C,

Tuveson DA and Vonderheide RH: Dynamics of the immune reaction to

pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res.

67:9518–9527. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Younos IH, Dafferner AJ, Gulen D, Britton

HC and Talmadge JE: Tumor regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor

cell proliferation and trafficking. Int Immunopharmacol.

13:245–256. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sawanobori Y, Ueha S, Kurachi M, Shimaoka

T, Talmadge JE, Abe J, Shono Y, Kitabatake M, Kakimi K, Mukaida N,

et al: Chemokine-mediated rapid turnover of myeloid-derived

suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Blood. 111:5457–5466. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lean JM, Murphy C, Fuller K and Chambers

TJ: CC L9/MIP-1gamma and its receptor CCR1 are the major chemokine

ligand/receptor species expressed by osteoclasts. J Cell Biochem.

87:386–393. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yan HH, Jiang J, Pang Y, Achyut BR,

Lizardo M, Liang X, Hunter K, Khanna C, Hollander C and Yang L:

CCL9 induced by TGFβ signaling in myeloid cells enhances tumor cell

survival in the premetastatic organ. Cancer Res. 75:5283–5298.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kitamura T, Fujishita T, Loetscher P,

Revesz L, Hashida H, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Aoki M and Taketo MM:

Inactivation of chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 (CCR1) suppresses

colon cancer liver metastasis by blocking accumulation of immature

myeloid cells in a mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:13063–13068. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Fujimi S, Lapchak PH, Zang Y, MacConmara

MP, Maung AA, Delisle AJ, Mannick JA and Lederer JA: Murine

dendritic cell antigen-presenting cell function is not altered by

burn injury. J Leukoc Biol. 85:862–870. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gatto D, Wood K, Caminschi I,

Murphy-Durland D, Schofield P, Christ D, Karupiah G and Brink R:

The chemotactic receptor EBI2 regulates the homeostasis,

localization and immunological function of splenic dendritic cells.

Nat Immunol. 14:446–453. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang S, Li ZF, Pan D, Huang C, Zhou R and

Liu ZW: Changes of splenic macrophage during the process of liver

cancer induced by diethylnitrosamine in rats. Chin Med J.

122:3043–3047. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|