Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common malignant

carcinomas amongst women worldwide. There are an estimated 530,000

new cases of cervical cancer annually with 270,000 cancer-related

deaths (1,2). Infection with high-risk human

papillomaviruses (HPVs), such as HPV16 and HPV18, is the primary

cause of cervical cancer, amongst multiple factors (3). Understanding that HPV infection is the

primary inducer of development of cervical cancer has improved

prevention of cervical cancer (4). At

present, the strategies for treatment of cervical cancer include

surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. However, the severe systemic

toxicity caused by radiation and chemotherapy affect prognosis

(4–7).

Therefore, developing a safe therapeutic strategy for cervical

cancer treatment is desirable.

Isolating components of traditional medicines with

antineoplastic activities has been demonstrated as a promising

alternative strategy for treating patients with cancer (8,9).

Tanshinone II A (Tan IIA) is the primary lipophilic component

isolated form the traditional Chinese medicine Salvia

miltiorrhiza. Numerous animal and clinical studies have

demonstrated that Tan IIA is an effective reagent commonly used for

the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, including

atherosclerosis via its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

activities (10–12). Tan IIA has recently attracted

considerable attention in cancer therapy due to its potential

antitumor activities. The antitumor effect of Tan IIA has been

verified in various cancer cell lines, including glioma,

osteosarcoma, leukemia, prostate, breast, colon, lung, liver,

stomach, pancreas, bile duct, kidney, ovarian, cervical and

nasopharyngeal cells (13–16). Studies have demonstrated that Tan IIA

may suppress the growth and induce apoptosis in certain types of

cancer cells through multiple mechanisms, including cell cycle

arrest and caspase-dependent apoptosis (17,18).

However, the antitumor mechanisms of Tan IIA remain unknown.

Over the last decade, advances in understanding of

the metabolism in cancer cells has revealed that cancer cells

predominantly rely on aerobic glycolysis to maintain cell

proliferation (19,20). Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis in

tumors has been identified as an effective strategy to aid in

overcoming obstacles in cancer treatment, and the effectiveness of

this approach has been validated in pre-clinical studies (21). Inhibiting glycolysis in a tumor may be

an effective treatment strategy for potential future treatments

(22–24).

Several studies have reported that Tan IIA inhibits

proliferation in cervical cancer cells by inducing apoptosis in

these cells (25,26). However, previous research has only

focused on the use of Tan IIA to induce tumor cell apoptosis. The

role of Tan IIA on inhibition of glycolysis in cervical cancer has

not been studied. The aim of the present study was to examine the

effect of Tan IIA on cell growth in cervical cancer and determine

the underlying mechanism, by assessing change in metabolic

phenotype and apoptosis. The present study provides insight into

the molecular mechanism through which Tan IIA induces apoptosis in

cervical cancer and highlights the potential use of Tan IIA as a

novel therapeutic agent for treating patients with cervical

cancer.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human cervical cancer cell lines SiHa (HPV

16-positive cells), HeLa (HPV 18-positive cells) and C33a (HPV

negative) were provided by the Chinese Academy of Sciences

(Shanghai, China). Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) and

fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, analytical grade) was

obtained from Beijing Chemical Reagent Factory. Tan IIA was

obtained from PhytoMyco, Inc. The mouse anti-human Bcl-2 antibody

(cat. no. sc-23960), mouse anti-human Bax antibody (cat. no.

sc-20067), rabbit ant-human cleaved caspase-3 antibody (cat. no.

sc-7148), mouse anti-human cleaved caspase-9 antibody (cat. no.

sc-17784), mouse anti-human cytochrome c antibody (cyto

c; cat. no. sc-13561) were obtained from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. Rabbit ant-human p-AKT antibody (ID product

code ab18206), rabbit ant-human AKT antibody (ID product code

ab8805), rabbit ant-human p-mTOR antibody (ID product code

ab84400), rabbit ant-human mTOR antibody (ID product code ab2732)

were obtained from Abcam, Inc. Rabbit ant-human GLUT1 antibody

(cat. no. PA5-16793), rabbit ant-human PKM2 antibody (cat. no.

PA5-23034), rabbit ant-human HK2 antibodies (cat. no. PA5-29326)

were purchased from Invitrogen; Thermo Fsiher Scientific, Inc.

Cell culture

SiHa, HeLa and C33a cells were maintained in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml of penicillin and 100

units/ml of streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5%

carbon dioxide (CO2) and 95% air. Cells were

sub-cultured every three days with 0.25% trypsin.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of Tan IIA on tumor cells was

detected by MTT assay (27). SiHa,

HeLa and C33a cells were seeded into a 96-well assay plate with a

concentration 1.0×105 cells/ml (200 µl/well). After 24 h

of incubation, the cells were treated with Tan IIA with doses of

0–8 mg/l in the growth medium. Each concentration was assessed five

times. The cells were cultured for another 24, 48 and 72 h.

Subsequently, 20 µl of MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and

incubated for another 4 h. Then, supernatant was discarded and 150

µl DMSO was loaded to each well. The optical density (OD) was

measured at 490 nm using a Bio-assay reader (Bio-Rad 550; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

(qRT-PCR)

The total RNA form Tan IIA-treated and untreated

SiHa cells were extracted to detect the expression of HPV16-E6/E7

gene. Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as per the

manufacturer's protocol. A high-capacity cDNA reverse-transcription

kit was used to prepare cDNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc).

qRT-PCR was carried out using gene-specific oligonucleotide primers

(Table I), an iScript One-Step RT-PCR

kit with SYBR-Green and an ABI 7500 Fast real-time PCR system. The

PCR conditions were set as 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at

95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 30 min. All values

were normalized to β-actin and then standardized to the control

condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

(SEM), and the statistical significance was assessed using the

Student's t-test. After completion of the RT-PCR, Cq values were

obtained using the ABI 7500 fast v2.0.1 software. The ΔΔCq method

was used to represent mRNA fold change (28).

| Table I.Sequences of primers for qRT-PCR. |

Table I.

Sequences of primers for qRT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|

| E6 |

GAGCGACCCAGAAAGTTACCA |

AAATCCCGAAAAGCAAAGTCA |

| E7 |

CATGGAGATACACCTACATTGC |

CACAACCGAAGCGTAGAGTC |

Fluorescence microscope-detected

apoptosis

SiHa cells were cultured on slides at a density of

5×104/ml in 24-well plates. After Tan IIA treatment, the

medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS twice. Then,

the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 25°C.

Subsequently, the cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 for 5 min

at 25°C. The apoptosis morphology was observed using a fluorescence

microscope. The images were captured at magnifications of ×200.

Flow cytometric evaluation of

apoptosis

After Tan IIA treatment, SiHa cells were harvested

by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 3 min and washed with PBS twice.

After that the harvested cells pellet was resuspend in 100 µl DMEM

medium. Then 100 µl Muse Annexin V and Dead Cell reagents were

added and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The percentage

of apoptosis was detected and analyzed using a Muse Cell Analyzer

(EMD Millipore).

Caspase-3/7 activation detected

The caspase-3/7 activation change was detected by

Muse Cell Analyzer following the manufacturer's instructions. After

Tan IIA treatment, SiHa cells were harvested by centrifugation at

850 × g and the cell pellet was resuspended in 50 µl PBS. Muse

Caspase-3/7 reagent working solution (5 µl) was added to the cell

suspension, and it was mixed thoroughly and incubated at 37°C for

30 min. After incubation, 150 µl of Muse™ Caspase 7-AAD working

solution was loaded to each sample, and incubated at room

temperature for 5 min. Then, the caspase-3/7 activation was

detected by Muse Cell Analyzer.

Measurements of glucose uptake levels

and lactate production

The SiHa cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a

density of 1×104 cells/well. After treatment with Tan

IIA for 48 h, the cell culture media was collected to detect the

glucose uptake and lactate production. For assessment of lactate

production, the collected culture media was diluted 1:50 by using

lactate assay buffer. The amount of lactate present in the media

was then estimated using the Lactate Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

content of glucose in the collected culture media was detected

immediately using a Glucose Assay kit according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Glucose uptake and lactate production

were all normalized by cell number (29).

Determination of ATP content

SiHa cells were seeded in 6-well plates

(1×105 cells/ml) and then incubated with Tan IIA for 48

h. Then, the cells were harvested and lysed on ice with somatic

cell ATP releasing reagent. The ATP content was detected by ATP

assay kits (Genmed Scientifics, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. ATP content was normalized by cell

number (29).

Western blot analysis

After Tan IIA treatment, 5×105 SiHa cells

were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

to extract the total protein. The extract total protein content was

determined by Bio-Rad BCA protein assay kit and 50 µg protein/lane

was loaded on 12% SDS-PAGE. After SDS-PAGE, the separated proteins

were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Non-specific binding

was blocked by incubating nitrocellulose membranes in 5% non-fat

dry milk in TBS/0.1% Tween for 120 min. After blocking, the blots

were incubated with primary antibody: Bcl-2 antibody (dilution

1:2,000), Bax (dilution 1:2,000), cleaved caspase-3 (dilution

1:2,000), cleaved caspase-9 (dilution 1:2,000), cyto c

antibody (dilution 1:2,000), p-AKT (dilution 1:1,000), AKT

(dilution 1:1,000), p-mTOR (dilution 1:1,000), mTOR (dilution

1:1,000), GLUT1 (dilution 1:1,000), PKM2 (dilution 1:1,000), HK2

(dilution 1:1,000) at 4°C overnight. Then, the appropriate

secondary antibody (cat. nos. sc-2357 and sc-516132; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology) at a 1:5,000 dilution was added and incubation

followed for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive protein bands

were detected by chemiluminescence using enhanced chemilumunescence

reagents (ECL) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Blots were also stained with anti-β-actin antibody (cat. no.

60008-1-Ig; Proteintech Group) as an internal control for the

amounts of target proteins. The films were then subjected to

densitometry analysis using a Gel Doc 2000 system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

In vivo antitumor test

All animal experiments were performed in compliance

with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee for Animal Use and Care

of Beihua University. This committee approved the experiments in

the present study. Kunming (KM) female mice (n=25) were purchased

from Jilin University (8 weeks old; 20–25 g). The animals were

maintained under a dedicated room with a 12-h light/dark cycle at a

constant temperature of 22°C.

First, U14 cervical cancer cells obtained from The

Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) were harvested by

trypsin digestion, washed by PBS, and re-suspended in serum-free

RPMI-1640 medium. U14 cervical cancer cell suspension (0.2 ml) with

a density of 5×106 was injected into the right

infra-axillary dermis of the mice. When the size of the tumor

reached 150 mm3, the mice were randomly assigned to 5

groups with 5 mice in each group: Control, cyclophosphamide (CTX;

25 mg/kg/day, i.g.), and three doses of Tan IIA (40 mg/kg/day; 20

mg/kg/day; and 10 mg/kg/day). The tumor volume and body weight were

measured every two days for 14 days. The relative tumor volume

Vt/V0 as a function of time was used to

investigate the inhibitory effect. All groups were treated every

two days for 20 days, and 24 h after the last administration, the

mice of the four groups were sacrificed. The tumors were excised to

evaluate tumor inhibition. The tumor inhibition rate was calculated

by the formula: Inhibitory rate (IR) = (the tumor weight of the

control group - the tumor weight of the treated group/the tumor

weight of the control group) ×100%. For euthanasia, animals were

anesthetized with 5% isoflurane vaporized in oxygen and thereafter

euthanatized with a 20% container volume/min gas replacement rate

of carbon dioxide. Euthanasia was confirmed when the heartbeat

stopped and the pupils were enlarged.

Histopathological and morphological

examination

The tumor tissues were excised and fixed at 25°C for

one week in 4% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-mm

sections for histological study. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

purchased form Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA) was used to stain the

tumor for histological analysis. Histopathological analysis of the

tumor tissue sections was performed using a light microscope at an

×200, magnification.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM which are

derived from three or more independent experiments. All data were

analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS version 13 software (SPSS,

Inc.). Tukey's post hoc test was used to determine the significance

for all pairwise comparisons of interest. A value of P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Tan IIA inhibits the cell viability

against human cervical cancer cells

An MTT assay was performed to determine the

cytotoxicity of Tan IIA in SiHa, HeLa, and C33a cells after 48 h of

treatment. The results revealed that Tan IIA significantly

inhibited cell viability in SiHa, HeLa and C33a cells in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Tan

IIA had a greater inhibitory effect on cell viability in SiHa and

HeLa cells compared with the HPV-negative C33a cells. Thus, SiHa

cells were used for all subsequent experiments.

| Figure 1.Tan IIA inhibits the cell viability

of human cervical cancer cells and decreases the expression of HPV

oncogenes. (A) Tan IIA inhibited the cell viability of SiHa, HeLa,

and C33a cells in a dose-dependent manner. Cells were treated with

increasing concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 mg/l) of Tan

IIA for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. (B)

Effect of Tan IIA on the mRNA expression levels of HPV16 E6 and E7

in SiHA cells. (C) Western blotting revealed the expression of HPV

oncogenes in SiHa cells treated with Tan IIA. (D) Densitometry

analysis of the blots presented in C. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation (SD), n=5. **P<0.01 compared with the

control. Tan IIA, tanshinone IIA; HPV, human papillomavirus. |

Tan IIA suppresses HPV16-E6/E7 gene

expression

The effect of Tan IIA expression on mRNA expression

of HPV16-E6/E7 in SiHa cells was determined using reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR (Fig. 1B). Treatment with Tan IIA (1.5 mg/l)

resulted in a significant reduction in the mRNA expression of HPV

E6 and HPV E7. Western blot analysis also confirmed the results of

the RT-qPCR (Fig. 1C).

Tan IIA induces SiHa cell

apoptosis

Hoechst 333258 was used to stain apoptotic nuclei.

Hoechst 333258 staining revealed that the nuclei appeared as

uniform blue with organized chromatin structure in the control

group (Fig. 2A). Following treatment

with Tan IIA at a range of concentrations (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/l) for

48 h, the SiHa cells were decreased in number and presented with

smaller nuclei, strong fluorescent spots, pyknotic nuclei and

extensive blebbing. Condensed chromatin and apoptotic bodies were

observed under a fluorescence microscope in the treated cells

suggesting that the Tan IIA treatment had induced apoptosis in the

SiHa cells. Similar results were obtained from staining with Muse

Annexin V and Dead Cell reagents. As revealed in Fig. 2B and C the percentage of early

apoptotic cells was increased as the dose of Tan IIA increased

compared with the untreated group (P<0.01).

Detection of caspase-3/7

activation

Muse caspase-3/7 assay kits were used to detect

caspase-3/7 activation following treatment with Tan IIA in the SiHa

cells. Stained cells were quantified using a Muse cell analyzer.

The percentage of cells in early apoptosis was 4.9, 10.55, and

22.55% when treated with 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/l Tan IIA, respectively

(Fig. 2D and E).

Inhibitory effect of Tan IIA on

glucose uptake, lactate generation, and adenosine triphosphate

(ATP) production

Tumor cells use glucose as a substrate for ATP

synthesis and production. Glucose uptake in SiHa cells following

treatment with Tan IIA for 48 h was measured. The results revealed

that glucose uptake in Tan IIA-treated SiHa cells was decreased

(Fig. 3A). The primary product of

aerobic glycolysis is lactic acid and ATP. Thus, the ATP and lactic

acid content were measured using reagent kits to investigate

whether glycolysis inhibition was associated with Tan IIA-mediated

SiHa cell apoptosis. The results revealed that the levels of

intracellular ATP and extracellular lactic acid were decreased in

SiHa cells treated with Tan IIA (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/l) compared with

the control group (Fig. 3B and

C).

Tan IIA induces SiHa cell apoptosis

through the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway

Western blotting was used to assess the expression

of apoptosis-associated proteins in Tan IIA-treated SiHa cells to

determine which apoptosis pathway underlied Tan IIA activity in

apoptosis of cervical cancer cells. As revealed in Fig. 4, after treatment with increasing doses

of Tan IIA for 48 h, the expression levels of Bax, cleaved

caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-9 were significantly increased. Bcl-2

expression signficantly decreased. Thus, there was a dose-dependent

increase in the expression ratio of Bax/Bcl-2. In the Tan

IIA-treated SiHa cells, cyto c was released from the

mitochondria to the cytosol in a dose dependent manner.

Tan IIA downregulates the Akt/mTOR

signaling pathway and inhibits glycolysis

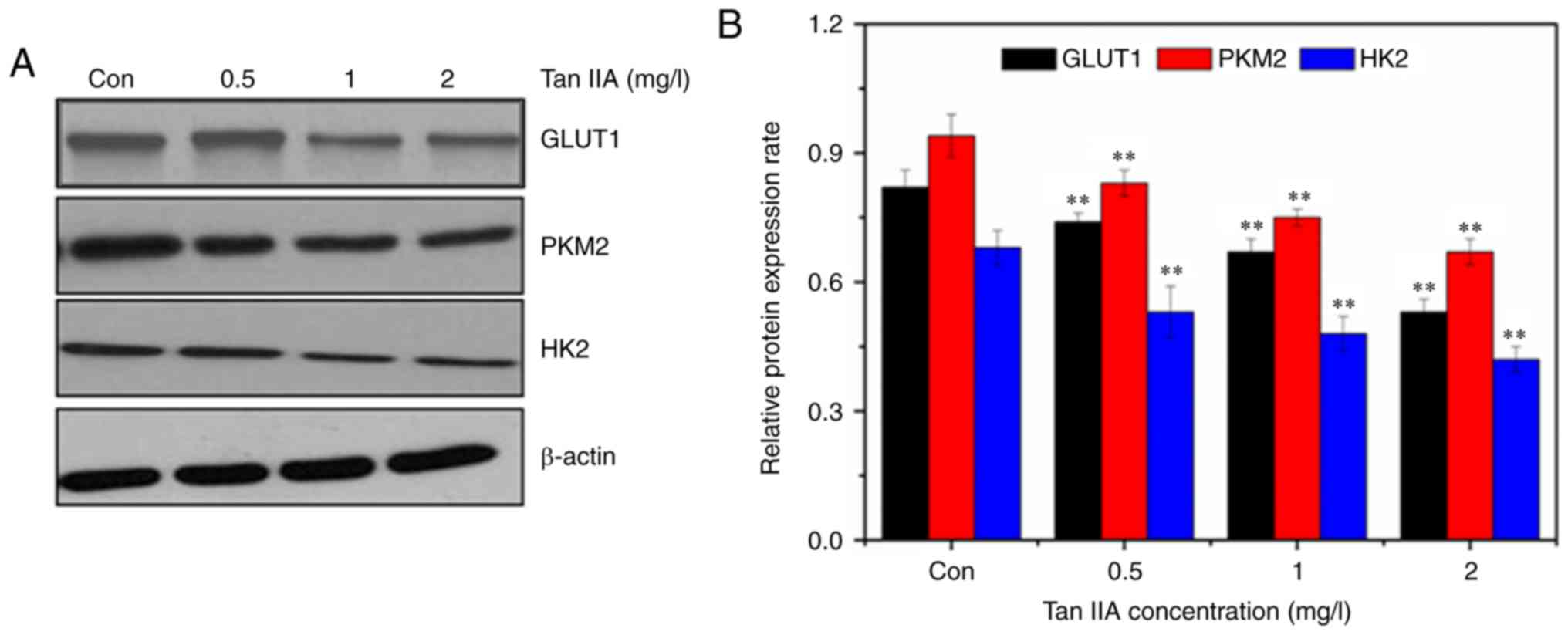

The expression of GLUT1 was detected by western

blotting. The western blot results revealed that Tan IIA decreased

the expression of GLUT1, PKM2, and HK2 (Fig. 5), confirming inhibition of glycolysis

in SiHa cells treated with Tan IIA. The AKT/mTOR pathway serves a

major role in the activation of aerobic glycolysis in tumors.

Therefore, it was determined whether the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

was involved in regulation of aerobic glycolysis in the Tan

IIA-treated SiHa cells. Treatment with Tan IIA resulted in a

dose-dependent decrease of the phosphorylation of Akt and mTOR

(Fig. 6). HIF-1α mediates

transformation of cell metabolism, whereas the PI3K/AKT pathways

are involved in the regulation of HIF-1α. As revealed in Fig. 6, Tan IIA inhibited the expression of

HIF-1α in SiHa cells.

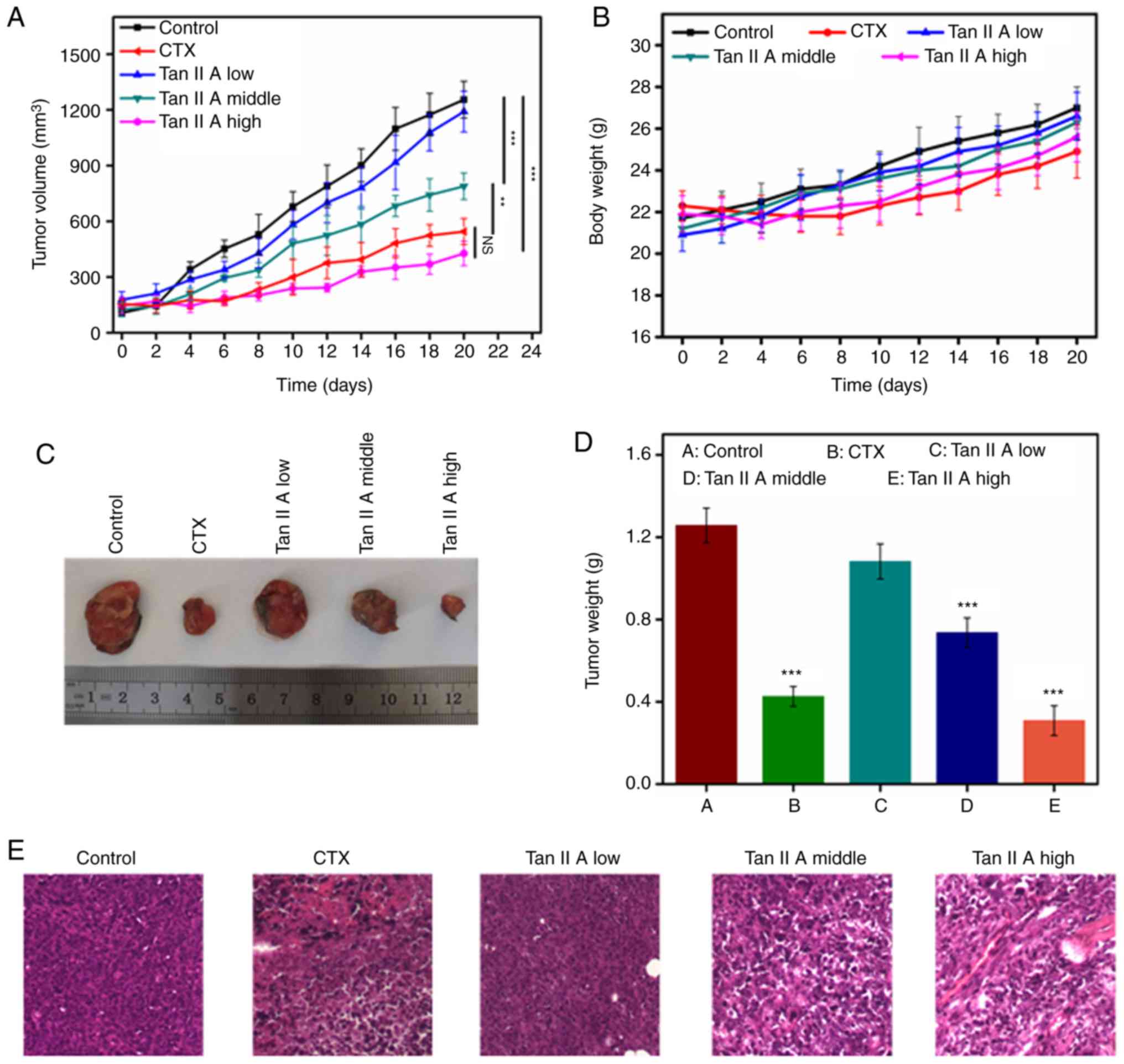

Effect of Tan IIA on tumor growth in

vivo

U14 tumor-bearing Kunming mice were used to

determine the antitumor effects of Tan IIA in vivo. When the

the tumor size of mice reached 150 mm3, they were

randomly divided into 5 groups. Mice were intraperitoneally

administered with CTX (25 mg/kg) and Tan IIA (three doses) for 14

days. As revealed in Fig. 7A, the

tumor in the control group grew rapidly, whereas the tumors in the

mice treated with CTX and Tan IIA grew significantly slower. The

body weight of the mice in the Tan IIA-treated group gradually

increased but did not significantly differ from the control group,

suggesting that Tan IIA did not demonstrate any significant toxic

effect. At the end of the experiment, the mice were sacrificed, and

the size of the tumors and tumor weights were measured. The results

revealed that the tumor weight and volume in the CTX- and Tan

IIA-treated groups decreased compared with the control group, in

which the high dose of Tan IIA resulted in mice with a tumor weight

similar to that in the CTX-treated group. The diameter of the tumor

in each group is revealed in Table

SI. The maximum tumor volume in each group is revealed in

Table SII. The tumor inhibition rate

in the CTX-treated group was 65.1%, whereas the rate in mice

treated with a high dose (40 mg/kg/day) of Tan IIA was 72.7%

(Fig. 7C and D and Table SIII). Pathological analysis of the

tumor tissues revealed that tumors in the U14 model group exhibited

invasive growth and rapid diffusion with high degrees of tumor cell

proliferation. CTX-treated tumor cells exhibited unclear structures

with regional necrosis, clear cell edema and a large number of

disintegrated granular cells. Following treatment with Tan IIA, the

tumor cells demonstrated regional necrosis, with shrunken cell

volumes, nuclear condensation and clear interstitial edema

occasionally infiltrated with inflammatory cells.

Discussion

The energy required for proliferation of cancer

cells is obtained by glycolysis which is less efficient than

aerobic oxidation of glucose (30).

The use of glycolysis as the predominant source of energy is

associated with certain factors, including upregulation of critical

enzymes involved in glycolysis and glucose transporters.

Concurrently, expression of enzymes involved in oxidative

phosphorylation is downregulated. High glycolytic metabolism has

been reported to be associated with resistance to apoptosis in

cancer following treatment with anticancer drugs (31,32). Tan

IIA has been demonstrated to inhibit cell viability of cervical

cancer by decreasing the expression of HPV oncogenes (26). However, the effect of Tan IIA on the

inhibition of glycolysis in cervical cancer is still unknown.

Therefore, in the present study, the effect of Tan IIA on inducing

apoptosis and inhibiting glycolysis in cervical cancer and its

possible mechanism were examined.

There are several subtypes of HPV, including

high-risk subtypes which are associated with cancer development

(33). More than 20 common subtypes

of high-risk HPVs exist, with HPV16 being the most prevalent

(34). The present study demonstrated

that Tan IIA markedly decreased the cell viability of SiHa, HeLa,

and C33a cervical cancer cells. Treatment with Tan IIA resulted in

a greater decrease in cell viability in SiHa cells compared with

HeLa and C33a cells. Therefore, SiHa cells (HPV 16-positive cells)

were selected to determine the mechanism underlying the effects of

Tan IIA. High-risk HPVs, including HPV16 and HPV18 result in the

expression of oncogenes, E6 and E7. E6 and E7 combine to tumor

suppressor p53 and Rb, individually. This causes p53 degradation

and loss of Rb products (35–37). The results of the present study

revealed that following treatment Tan IIA, the mRNA and protein

expression levels of E6 and E7 protein were decreased in SiHa

cells. Abnormal cell proliferation and differentiation, and

apoptotic imbalance are also important causes of tumorigenesis

(38). A number of chemotherapeutic

agents affect cancer cells, inducing apoptosis. Apoptotic cells

display characteristic morphological changes, such as cell

shrinkage, cytoplasmic vacuolation, chromatin condensation, nuclear

fragmentation, and cell blebbing, to produce apoptotic bodies

(39,40). Hoechst 333258 staining results

revealed typical apoptotic morphology in Tan IIA-treated SiHa

cells. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy revealed that the

number of apoptotic cells increased as the concentration of Tan IIA

was increased. The mechanism through which Tan IIA-induced

apoptosis was examined, and the results revealed a marked decrease

in Bcl-2 expression in the cells treated with Tan IIA,

significantly increased Bax expression levels, and an increased

Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (41). Bcl-2 is an

anti-apoptotic protein involved in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway

which inhibits apoptosis by binding and subsequently inhibiting

proapoptotic molecules, such as Bax and Bak (42). Therefore, changes in the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio may explain the increased rate of apoptosis in the Tan

IIA-treated SiHa cells.

Apoptotic factors, such as cyto c, serve a

crucial role in the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, activating the

activity of caspases in cancer cells. Chemotherapeutic agents and

cytotoxic drugs frequently induce the release of cyto c from

mitochondria into the cytosol resulting in activation of caspase-9.

Subsequently, pro-caspase-3 is transformed into its active form

(caspase-3) by caspase-9-mediated cleavage. Poly-ADP ribose

polymerase may be cleaved by caspase-3, causing DNA fragmentation

and apoptosis (43). The results of

the present study revealed that Tan IIA treatment resulted in the

release of cyto c from the mitochondria into the cytosol and

the activation of caspase-9 in SiHa cells. Subsequently, activated

caspase-9 impacted the downstream caspase-3 proenzyme and activated

caspase-3, ultimately inducing apoptosis in SiHa cells.

The researcher and scientist Warburg revealed a

phenomenon in which tumors prefer to utilize the energy which is

supplied by glycolysis instead of aerobic oxidation of glucose even

when there is an ample supply of oxygen. Anaerobic respiration in

cancer cells leads to a considerable increase in the use of glucose

(44,45). The results of the present study

revealed that Tan IIA treatment may suppress glucose uptake and

extracellular lactic acid generation in SiHa cells. GLUT1, PKM2,

and HK2 were all downregulated in the Tan IIA treatment group.

GLUT1 is an important glucose transporter, which is a rate-limiting

enzyme of glucose transport. Increased expression of GLUT1 is

associated with proliferation, migration and invasion (46). HK2 and PKM2 isozyme expression is

increased in a number of malignant types of cancer associated with

a propensity for invasion and metastasis (47). The Akt/mTOR signaling is associated

with hypoxia signaling transduction. At the translational level,

the phosphorylation of Akt and mTOR can increase the

hypoxia-induced expression of HIF-1α, which regulates intracellular

glucose utilization and angiogenesis, and promotes stabilization

and activation, eventually promoting tumor cell growth (48–50). The

results of present study revealed that Tan IIA treatment decreased

the expression of HIF-1α and concurrently decreased the

phosphorylation of Akt and mTOR in SiHa cells. This indicates that

regulation of HIF-1α by the Akt/mTOR pathway was involved in the

inhibition of glycolysis when treated with Tan IIA. In

vitro, Tan IIA demonstrated significant antitumor effects in

SiHa cells, and the possible mechanism was associated with

inhibition of glycolysis. Therefore, the antitumor effect of Tan

IIA in carcinoma-bearing mice was determined. The results of the

present study revealed that carcinoma-bearing mice treated with Tan

IIA presented with a significant reduction in the tumor volume and

weight and there was no notable difference in the toxicity between

the different groups of mice. The present study highlights the

potential of Tan IIA as a therapeutic alternative.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that

treatment with Tan IIA inhibited cell viability of cervical cancer

SiHa cells and induced apoptosis. The possible mechanism was

associated with the expression of the oncogenes E6 and E7,

decreasing glycolysis through inhibition of the intracellular

Akt/mTOR pathway and the associated HIF-1α signaling. Tan IIA

treatment increased apoptosis in SiHa cells, and this effect may be

associated with inhibition of glycolysis.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Project

Agreement for Science and Technology Development, Jilin Province

(nos. 20180101142JC, 20190701062GH, 20130101157JC) and the Science

and Technology Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Education

(JJKH20190662KJ, JJKH20191062KJ, no. 2011286).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

ZL, WZhu and WZhang performed the experiments and

participated in designing some experiments. XK and XC participated

in the experiment of cell experiment and western blot analysis. XS

and RZ performed the PCR and flow cytometry experiments, and WZhu,

WZhang and RZ performed some of the in vivo experiments.

WZhu wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the

manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of

the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were performed in compliance

with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee for Animal Use and Care

of Beihua University. This committee approved the experiments in

the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

Akt

|

protein kinase B

|

|

DMEM

|

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

GLUT1

|

glucose transporter 1

|

|

HIF-1α

|

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

|

|

HPVs

|

human papillomaviruses

|

|

p38

|

p38 mitogen-activated protein

kinases

|

|

PI3K

|

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

3-kinase

|

|

qRT-PCR

|

quantitative reverse transcription

PCR

|

|

MTT

|

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

|

|

Tan IIA

|

tanshinone II

|

References

|

1

|

Lecavalier-Barsoum M, Chaudary N, Han K,

Koritzinsky M, Hill R and Milosevic M: Targeting the CXCL12/CXCR4

pathway and myeloid cells to improve radiation treatment of locally

advanced cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 143:1017–1028. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Testa U, Petrucci E, Pasquini L, Castelli

G and Pelosi E: Ovarian cancers: Genetic abnormalities, tumor

heterogeneity and progression, clonal evolution and cancer stem

cells. Medicines (Basel). 5(pii): E162018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Scheffner M, Werness BA, Huibregtse JM,

Levine AJ and Howley PM: The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human

papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53.

Cell. 63:1129–1136. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wardak S: Human papillomavirus (HPV) and

cervical cancer. Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 68:73–84. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Suh DH, Kim M, Kim K, Kim HJ, Lee KH and

Kim JW: Major clinical research advances in gynecologic cancer in

2016: 10-year special edition. J Gynecol Oncol. 28:e452017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network;

Albert Einstein College of Medicine; Analytical Biological

Services; Barretos Cancer Hospital; Baylor College of Medicine;

Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope; Buck Institute for

Research on Aging; Canada's Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre;

Harvard Medical School; Helen F. Graham Cancer Center &

Research Institute at Christiana Care Health Services, et al, .

Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical

cancer. Nature. 543:378–384. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Palmer T and

Arbyn M: Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening.

J Clin Virol. 76 (Suppl 1):S49–S55. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fox BW: Medicinal plants in tropical

medicine. 2. Natural products in cancer treatment from bench to the

clinic. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 85:221991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pokrzywa CJ, Abbott DE, Matkowskyj KA,

Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Winslow ER, Weber SM and Fisher AV: Natural

history and treatment trends in pancreatic cancer subtypes. J

Gastrointest Surg. 23:768–778. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guo J, Ma X, Cai Y, Ma Y, Zhan Z, Zhou YJ,

Liu W, Guan M, Yang J, Cui G, et al: Cytochrome P450 promiscuity

leads to a bifurcating biosynthetic pathway for tanshinones. New

Phytol. 210:525–534. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li C, Han X, Hong Z, Wu J and Bao L: The

interplay between autophagy and apoptosis induced by tanshinone IIA

in prostate cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 37:7667–7674. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liao P, Hemmerlin A, Bach TJ and Chye ML:

The potential of the mevalonate pathway for enhanced isoprenoid

production. Biotechnol Adv. 34:697–713. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang Y, Jiang P, Ye M, Kim SH, Jiang C

and Lü J: Tanshinones: Sources, pharmacokinetics and anti-cancer

activities. Int J Mol Sci. 13:13621–13666. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fan G, Jiang X, Wu X, Fordjour PA, Miao L,

Zhang H, Zhu Y and Gao X: Anti-inflammatory activity of tanshinone

IIA in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages via miRNAs and

TLR4-NF-κB pathway. Inflammation. 39:375–384. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li Q, Shen L, Wang Z, Jiang HP and Liu LX:

Tanshinone IIA protects against myocardial ischemia reperfusion

injury by activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Biomed

Pharmacother. 84:106–114. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang S, Cang S and Liu D: Third-generation

inhibitors targeting EGFR T790M mutation in advanced non-small cell

lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 9:342016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cui ZT, Liu JP and Wei WL: The effects of

tanshinone IIA on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced myocardial

microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis in rats via the JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 83:1116–1126. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yano S, Takehara K, Ming Z, Tan Y, Han Q,

Li S, Bouvet M, Fujiwara T and Hoffman RM: Tumor-specific

cell-cycle decoy by Salmonella typhimurium A1-R combined with

tumor-selective cell-cycle trap by methioninase overcome tumor

intrinsic chemoresistance as visualized by FUCCI imaging. Cell

Cycle. 15:1715–1723. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Parr R, Harbottle A, Jakupciak JP and

Singh G: Mitochondria and cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2013:7637032013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhao E, Maj T, Kryczek I, Li W, Wu K, Zhao

L, Wei S, Crespo J, Wan S, Vatan L, et al: Cancer mediates effector

T cell dysfunction by targeting microRNAs and EZH2 via glycolysis

restriction. Nat Immunol. 17:95–103. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wen Z, Zhang SL, Hu X and Tam KY:

Targeting tumor metabolism for cancer treatment: Is pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs) a viable anticancer target? Int J Biol

Sci. 11:1390–1400. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Choe M, Brusgard JL, Chumsri S, Bhandary

L, Zhao XF, Lu S, Goloubeva OG, Polster BM, Fiskum GM, Girnun GD,

et al: The RUNX2 transcription factor negatively regulates SIRT6

expression to alter glucose metabolism in breast cancer cells. J

Cell Biochem. 116:2210–2226. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lu J, Chen M, Gao S, Yuan J, Zhu Z and Zou

X: LY294002 inhibits the Warburg effect in gastric cancer cells by

downregulating pyruvate kinase M2. Oncol Lett. 15:4358–4364.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lu W, Hu Y, Chen G, Chen Z, Zhang H, Wang

F, Feng L, Pelicano H, Wang H, Keating MJ, et al: Novel role of NOX

in supporting aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells with mitochondrial

dysfunction and as a potential target for cancer therapy. PLoS

Biol. 10:e10013262012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pan TL, Wang PW, Hung YC, Huang CH and Rau

KM: Proteomic analysis reveals tanshinone IIA enhances apoptosis of

advanced cervix carcinoma CaSki cells through mitochondria

intrinsic and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways. Proteomics.

13:3411–3423. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Radha M, Farrukh A, Jeyaprakash J and

Gupta RC: Tanshinone IIA inhibits viral oncogene expression leading

to apoptosis and inhibition of cervical cancer. Cancer Lett.

356:536–546. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mosmann T: Rapid colorimetric assay for

cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and

cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 65:55–63. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yu W, Yang Z, Huang R, Min Z and Ye M:

SIRT6 promotes the Warburg effect of papillary thyroid cancer cell

BCPAP through reactive oxygen species. Onco Targets Ther.

12:2861–2868. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gasparre G, Porcelli AM, Lenaz G and Romeo

G: Relevance of mitochondrial genetics and metabolism in cancer

development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 5(pii):

a0114112013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mathupala SP, Rempel A and Pedersen PL:

Aberrant glycolytic metabolism of cancer cells: A remarkable

coordination of genetic, transcriptional, post-translational, and

mutational events that lead to a critical role for type II

hexokinase. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 29:339–343. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vaz CV, Marques R, Alves MG, Oliveira PF,

Cavaco JE, Maia CJ and Socorro S: Androgens enhance the glycolytic

metabolism and lactate export in prostate cancer cells by

modulating the expression of GLUT1, GLUT3, PFK, LDH and MCT4 genes.

J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 142:5–16. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Protzel C, Knoedel J, Zimmermann U,

Woenckhaus C, Poetsch M and Giebel J: Expression of proliferation

marker Ki67 correlates to occurrence of metastasis and prognosis,

histological subtypes and HPV DNA detection in penile carcinomas.

Histol Histopathol. 22:1197–1204. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Varier I, Keeley BR, Krupar R, Patsias A,

Dong J, Gupta N, Parasher AK, Genden EM, Miles BA, Teng M, et al:

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of oropharyngeal carcinoma

related to high-risk non-human papillomavirus16 viral subtypes.

Head Neck. 38:1330–1337. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ristriani T, Fournane S, Orfanoudakis G,

Travé G and Masson M: A single-codon mutation converts HPV16 E6

oncoprotein into a potential tumor suppressor, which induces

p53-dependent senescence of HPV-positive HeLa cervical cancer

cells. Oncogene. 28:762–772. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Termini L, Boccardo E, Esteves GH, Hirata

R Jr, Martins WK, Colo AE, Neves EJ, Villa LL and Reis LF:

Characterization of global transcription profile of normal and

HPV-immortalized keratinocytes and their response to TNF treatment.

BMC Med Genomics. 1:29. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yu Y, Liu X, Yang Y, Zhao X, Xue J, Zhang

W and Yang A: Effect of FHIT loss and p53 mutation on HPV-infected

lung carcinoma development. Oncol Lett. 10:392–398. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hirokawa M, Kawabata Y and Miura AB:

Dysregulation of apoptosis and a novel mechanism of defective

apoptotic signal transduction in human B-cell neoplasms. Leuk

Lymphoma. 43:243–249. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Aschoff AP, Günther E and Jirikowski GF:

Tissue transglutaminase in the small intestine of the mouse as a

marker for apoptotic cells. Colocalization with DNA fragmentation.

Histochem Cell Biol. 113:313–317. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cha Y, Park DW, Lee CH, Baek SH, Kim SY,

Kim JR and Kim JH: Arsenic trioxide induces apoptosis in human

colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells through ROS. Cancer Res

Treat. 38:54–60. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhu W, Zhang W, Xu N, Li Y, Xu J, Zhang H,

Li Y, Lv S, Liu W and Wang H: Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis

and downregulates glucose metabolism in JF-305 pancreatic cancer

cells. Rsc Adv. 8:20692–20700. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Zhu W, Zhang W, Li Y, et al: Possible

mechanism of apoptosis induced by microwave radiation in human

cervical carcinoma cell HeLa. Radiat Protect. 22:378–2258.

2013.

|

|

43

|

Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H,

Wang K and Shao F: Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through

caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature. 547:99–103. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hou X, Hongzhi DU and Yuan S: Research

progress of tumor metabolism for antitumor drugs. Cancer Res Prev

Treat. 44:231–235. 2017.

|

|

45

|

Zhivotovsky B and Orrenius S: The Warburg

effect returns to the cancer stage. Semin Cancer Biol. 19:1–3.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

North PE, Waner M, Mizeracki A and Mihm MC

Jr: GLUT1: A newly discovered immunohistochemical marker for

juvenile hemangiomas. Hum Pathol. 31:11–22. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Qiu P, Man S, Yang H, Liu Y, Liu Z, Ma L,

Yu P and Gao W: Metabolic regulatory network alterations reveal

different therapeutic effects of cisplatin and Rhizoma paridis

saponins in Lewis pulmonary adenoma mice. RSC Adv. 6:115029–115038.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Dayan F, Bilton RL, Laferrière J, Trottier

E, Roux D, Pouyssegur J and Mazure NM: Activation of HIF-1alpha in

exponentially growing cells via hypoxic stimulation is independent

of the Akt/mTOR pathway. J Cell Physiol. 218:167–174. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang F, Zhang W, Guo L, Cheng J, Liu P and

Chen B: Gambogic acid suppresses hypoxia-induced HIF-1α/VEGF

expression via inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in multiple myeloma

cells. Blood. 124:52302014.

|

|

50

|

Yeh YH, Hsiao HF, Yeh YC, Chen TW and Li

TK: Inflammatory interferon activates HIF-1α-mediated

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 37:702018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|