Introduction

At present, lung cancer has the highest mortality

rate among all malignant tumors (1).

According to statistics, as of 2018, lung cancer accounted for

11.6% of all cancer cases and cancer-related mortality (2). It is well known that smoking, air

pollution and chronic lung disease are all common causes of lung

cancer (3,4). Although early screening for lung cancer

is widespread, most patients are diagnosed at the terminal stage

and have a poor prognosis. Despite current popular targeted therapy

and immunotherapy, it remains difficult to achieve satisfactory

results (5,6). Determining the stage of lung cancer is

required for treatment but it also important for evaluating

prognosis. Based on the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee

on Cancer, the size of the tumor, number of lymph nodes and sites

of distant metastasis are the three major factors for determining

cancer stage (7). Lung cancer can be

divided into non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC, then

NSCLC can be further characterized into lung adenocarcinoma, lung

squamous cell cancer and large cell cancer (8). Moreover, NSCLC is the most common

pathological type. At present, providing a novel target for the

molecular diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC has become a hotspot in

basic research.

Thyroid hormone receptor-interacting protein 13

(TRIP13) is one of the most important members of the ATPase family

associated with various cellular activities (AAA+) ATPase family,

which is associated with cell cycle checkpoint and DNA repair

(9,10). TRIP13 participates in numerous

cellular physiological processes, including chromosome checkpoints,

DNA break repair and chromosome synapsis (11). The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC),

which is closely associated with chromosome repair, ensures that

all chromosomes produce bipolar spindle structures before mitosis

occurs (12,13). The participation of TRIP13 affects the

formation of SAC structure. For example, Tao et al (14) reported that overexpression of TRIP13

promoted multiple myeloma cell proliferation by invalidating

checkpoints via the Akt pathway. TRIP13 is an oncogene considered

to be involved in the progression of multiple tumor types, such as

hepatocellular carcinoma (15,16),

colorectal cancer (17), bladder

cancer (18) and prostate cancer

(19), and is associated with a poor

prognosis. Zhang et al (20)

revealed that TRIP13 may promote the malignant progression of NSCLC

and may be a potential target. Furthermore, TRIP13 knockdown could

arrest lung cancer cells in the G2/M phase, and it could

regulate the expression levels of genes associated with cell cycle

checkpoints. However, the mechanism of TRIP13 influencing the

invasion and metastasis of NSLCL has not been fully elucidated.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) serves an important

role in tumor metastasis by enhancing the motility of cancer cells

(21). At present, the mechanism of

TRIP13 influencing EMT process remains unknown and should be

further investigated.

The present study aimed to examine the association

of TRIP13 with NSCLC. Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-qPCR)

and western blot analyses were conducted to assess the role of

TRIP13 in regulating apoptosis, proliferation, invasion and

migration. Furthermore, knockdown or overexpression of TRIP13 may

affect the EMT during the progression of tumors. Studying the

molecular biological mechanism underlying the occurrence and

development of NSCLC and identifying effective biomarkers are

extremely important.

Materials and methods

Clinical information and bioinformatic

analyses

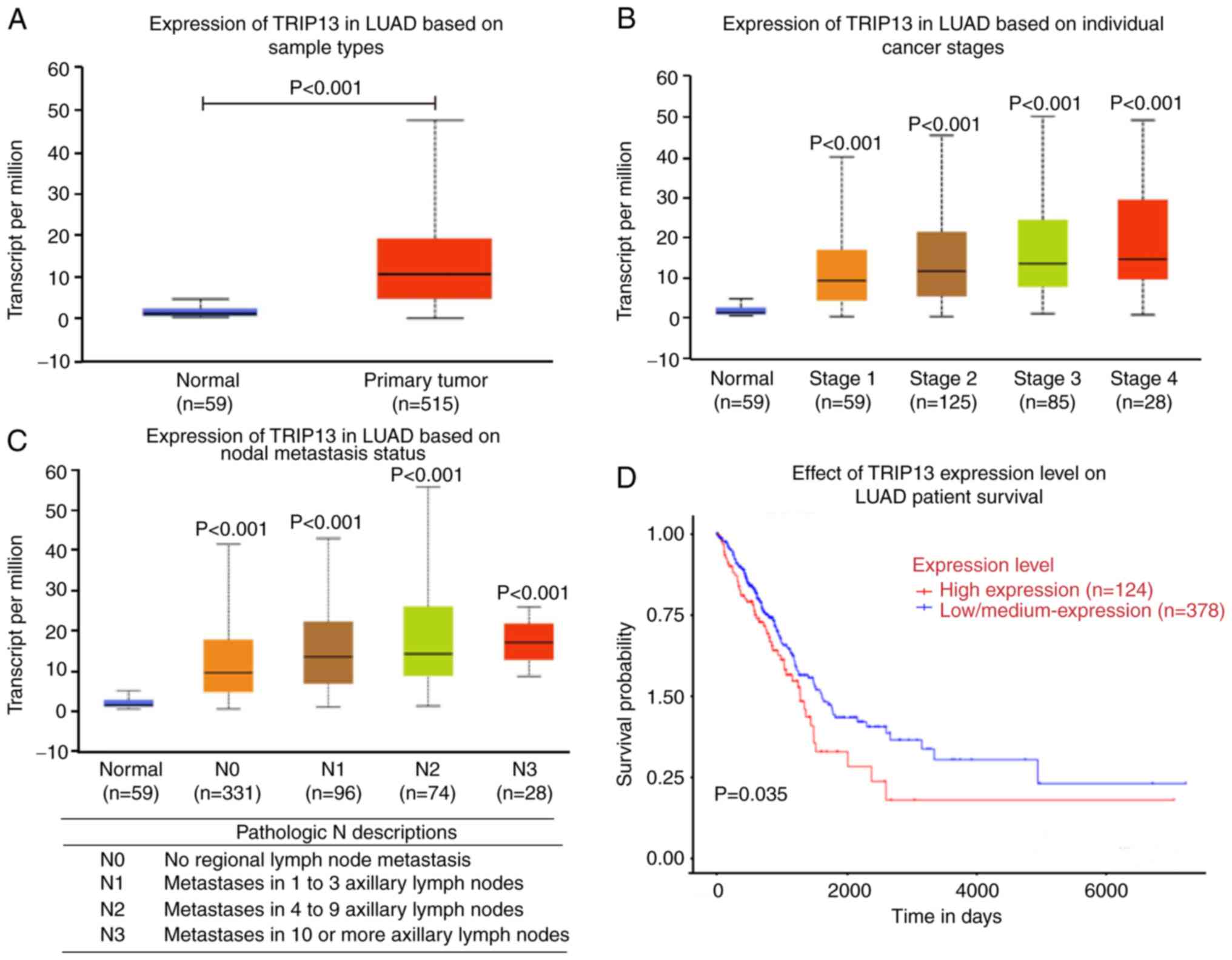

The clinical information of patients and mRNA

expression levels of TRIP13 were obtained for NSCLC tissues (n=515)

and adjacent normal tissues (n=59) from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) database (https://cancer.gov/). These tissues

were obtained from 238 men and 276 women. The age of patients

ranged from 40–80 years. The relationships between TRIP13 and

different stages of NSCLC, as well as numbers of axillary lymph

node metastases are presented. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed

to evaluate the prognostic value of TRIP13 at high level (n=124)

compared with low level (n=378) according to data from TCGA

database. The threshold of optimal gene expression was set as the

cut-off. The log-rank test was used to further evaluate the

P-value.

Cell culture and cell

transfection

Human NSCLC cell lines, A549, H1299 and H661, were

purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Cells were cultured

in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with

10% FBS (Cell Sciences) in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2 at 37°C. Small interfering (si)RNA negative control

(si-NC) and TRIP13 siRNA molecules (si1 and si2), pcDNA-3.1 vector

(empty vector) and TRIP13-overexpressing plasmid were purchased

from Suzhou GenePharma Co., Ltd. The cells were maintained in

6-well plates until they reached 60–70% confluence. According to

the manufacturer's instructions, the siRNAs (2.5 µg) and

overexpression plasmid (2.5 µg) were transfected into A549 and

H1299 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature and the medium

with serum was changed after 6 h. RNA was extracted 48 h after

transfection to verify the knockdown and overexpression effects.

All experiments were repeated three times. The siRNA sequences

were: si1, 5′-GACCAGAAAUGUGCAGUCU-3′; si2,

5′-GCAAAUCACUGGGUUCUAC-3′; and si-NC,

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT−3′.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from NSCLC cell lines and

tumor tissues using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Then, the RNA was reverse transcribed

into cDNA using PrimeScript RT Master mix (Takara Bio, Inc.). The

RT conditions were 37°C for 15 min, 85°C for 5 sec and 4°C

preservation. The expression level of TRIP13 was determined via

RT-qPCR using SYBR Green Master mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

a Bio-Rad Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). The complete thermocycling conditions were: Initial

denaturation at 95C° for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing and elongation at 60°C

for 30 sec, and the final extension at 72°C for 7 min. β-actin was

the internal control. The expression level of the relevant genes

was calculated using the formula 2−∆∆Cq (22). All experiments were repeated three

times. The primer sequences were as follows: TRIP13 forward,

5′-GCGTGGTCAATGCTGTCTTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CACGTCGATCTTCTCGGTGA-3′

and β-actin forward, 5′-CCAACCGCGAGAAGATGA−3′ and reverse,

5′-CCAGAGGCGTACAGGGATAG-3′.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Paraffin-embedded NSCLC tissues (n=10) were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature, then cut

into 5-µm paraffin sections and attached to slides. After dewaxing

with xylene for 30 min at room temperature, the slices were boiled

for 10 min in citric acid buffer solution (pH 6.0) for antigen

repair, blocked with 10% non-immune goat serum (LMAI Bio) for 30

min at room temperature and incubated with an antibody against

TRIP13 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab204331; Abcam) overnight at room

temperature. Then, the slices were incubated with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. ab205718; Abcam) for 30 min

at room temperature. After diaminobenzidine staining, the degree of

staining was observed under a fluorescent microscope. There was a

total of 10 patients, consisting of 5 men and 5 women. The age of

patients ranged 44–70 years. The following samples were collected:

Five tissues in right upper lobe, five tissues in right lower lobe,

one tissue in left upper lobe and one tissue in left lower lobe.

Moreover, the paired adjacent normal tissues were also obtained

from these patients. All tissues were obtained between March 2020

and November 2020. All samples came from patients at The Third

People's Hospital of Nantong Affiliated to Nantong University.

Informed consent was obtained from each patient. This study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of The Third People's Hospital of

Nantong Affiliated to Nantong University. All experiments were

repeated three times.

Cell apoptosis assay

The apoptotic rate was measured via flow cytometry

and included the percent of early and late apoptotic cells. After

transfection, the dead cells were collected and stained with 5 µl

Annexin V PE and 5 µl 7-AAD (BD Biosciences) in the dark at room

temperature for 15 min. In total, ~400 µl diluted binding buffer

was added to each sample. Then, the apoptotic rate was measured

using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the

results were analyzed using FlowJo software 10.7 (FlowJo LLC). All

experiments were repeated three times.

Cell cycle assay

Human A549 and H1299 cells were transfected with the

siRNAs or overexpression plasmid for 48 h. The cells were

resuspended in 70% ethanol and incubated in a −20°C freezer for

>24 h. The samples were stained with 20 µg/ml PI and 20 µg/ml

RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 15 min at room temperature.

Flow cytometry (BD Biosciences) was used to analyze cell cycle

progression, and the data were processed using FlowJo software 10.7

(FlowJo LLC). All experiments were repeated three times.

Cell proliferation assay

The proliferation of the NSCLC cells was measured

using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies,

Inc.) assay, according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total

of 4×103 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates

and cultured for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. After incubation with 10 µl

CCK-8 solution for 2 h at 37°C, the absorbance values were measured

at 450 nm. All experiments were repeated three times.

Transwell assay

Transwell assays were performed to detect cell

invasion and migration. For the invasion assay, a total of 40 µl

Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was diluted with serum-free medium and

placed in the upper chamber (pore size, 3 µm; MilliporeSigma) for

30 min at 37°C, and 2×105 cells were plated in the upper

chamber with 200 µl serum-free medium. DMEM with 20% FBS was added

to the lower chamber. For the migration assay, Matrigel was not

required in the upper chamber. After incubation for 48 h at 37°C,

the cells that adhered to the lower surface of the filter were

stained with 1% crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature.

Then, the quantity of invading or migrating cells was determined

under an Olympus IX73-FL-PH inverted microscope (Olympus

Corporation). All experiments were repeated three times.

Wound healing assay

A549 and H1299 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate

using medium with FBS-free for 24 h after transfection and covered

70–80% of the plate. A straight line was scratched the plate with a

10-µl pipette tip and every line was spaced at 0.5 cm. PBS was used

to removed cell debris. The cell healing was filmed at 0 and 24 h

using an Olympus IX73-FL-PH inverted microscope (Olympus

Corporation). The distance of lines was measured using ImageJ 1.8.0

(National Institutes of Health). All experiments were repeated

three times.

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from cells with RIPA

lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), and the

concentrations of the proteins were measured using a BCA protein

assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The samples were

mixed with loading buffer, were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE

gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). The

membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 2 h at room temperature and incubated overnight

at 4°C with primary antibodies [anti-TRIP13, anti-β-actin,

anti-vimentin, anti-E-cadherin, anti-snail family transcriptional

repressor 1 (Snail)]. The membranes were completely washed three

times with TBS-Tween-20 (0.1%) (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and further incubated with a specific HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. ab205718; Abcam) for 1 h at

room temperature. The densitometry was measured using ImageJ 1.8.0.

All experiments were repeated three times. The primary antibodies

were anti-TRIP13 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab204331; Abcam), anti-β-actin

(1:2,000; cat. no. ab8227; Abcam), anti-vimentin (1:1,000; cat. no.

5741S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-E-cadherin (1:1,000;

cat. no. 3195S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-Snail

(1:1,000; cat. no. NBP2-27293; Novus Biologicals, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as the mean ± SD. Most of

the differences between two groups were determined using an

unpaired t-test. The expression level of TRIP13 between NSCLC

tissues and adjacent normal tissues detected via RT-qPCR was

compared using a paired Student's t-test. Multiple comparison

between the group was performed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. All the data statistical analyses were

conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

TRIP13 is upregulated in NSCLC

To study the expression of TRIP13 in NSCLC, clinical

data from TCGA, including data from 59 normal samples and 515

primary tumor samples, were analyzed. It was found that TRIP13 was

upregulated in the NSCLC tissues compared with the adjacent normal

tissues (Fig. 1A). The data

demonstrated that the expression level of TRIP13 was more

significantly increased with higher stages of NSCLC, and each stage

was statistically significant compared with the normal group

(Fig. 1B).

To further evaluate the effect of TRIP13 expression

on prognosis, four cancer stages were identified based on the

number of axillary lymph nodes affected. As the number of affected

nodes increased, the expression level of TRIP13 was significantly

upregulated in the NSCLC tissues compared with the normal tissues,

and increased TRIP13 expression predicted poor prognosis (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the survival analysis

revealed that patients with high TRIP13 levels (n=124) had poorer

prognosis compared with those with low TRIP13 levels (n=378)

(Fig. 1D).

IHC analysis identified that the nuclei were stained

yellow brown or dark brown and that TRIP13 was located in the

nucleus in 10 NSCLC tissues (Fig.

2A). The results of TRIP13 positive cells were assessed by two

pathologists who did not know the tumor grade. In total, 10

high-power fields were observed and the positive percentage was

calculated. The quantitative data are shown in Fig. 2B. To determine the biological function

of TRIP13 in NSCLC cells, three cell lines, namely, A549, H1299 and

H661 cell lines, were selected for the experiment (Fig. 2C). The expression level of TRIP13 was

low in A549 cells, but its expression was high in H1299 cells.

Knockdown of TRIP13 inhibits the

proliferation, invasion and migration and increases apoptosis of

H1299 cells

si1 and si2 were used to knockdown the expression of

TRIP13 in H1299 cells, which had a higher endogenous TRIP13

expression than the other cell lines. The RT-qPCR results revealed

that the knockdown efficiency of si1 and si2 was substantial, and

that the expression of TRIP13 was knocked down (Fig. 3A). To further study the cellular

biological functions, a CCK-8 assay was used to examine the

proliferative abilities of the cells at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. The

knockdown of TRIP13 in H1299 cells significantly suppressed

proliferation compared with the NC group (Fig. 3B) from 24 to 72 h. Moreover, the

knockdown of TRIP13 inhibited the H1299 cell migratory and invasive

abilities, as evaluated using the Transwell assay (Fig. 4A). The wound healing experiment

effectively detected lateral cell migration. The migratory ability

of the knockdown group was significantly decreased compared with

the NC group, as determined by comparing the gaps in the wound

healing assay (Fig. 4B).

Flow cytometry accurately detected cellular

apoptosis and the cell cycle progression. The change in the

apoptotic rate could be one of the mechanisms that affect the

malignant progression of NSCLC. The results indicated that

knockdown of TRIP13 increased the rate of apoptosis in H1299 cells

compared with the NC at 48 h after transfection (Fig. 5A). In addition, the distribution of

the cell cycle reflected the stage of DNA synthesis in cancer

cells. In the TRIP13 knockdown group, there was a significant

decrease in the number of cells in the G1 phase; on the

other hand, TRIP13 knockdown induced H1299 cell cycle arrest in the

S phase and caused no changes in the number of cells in the

G2 phase (Fig. 5B).

TRIP13 overexpression inhibits

apoptosis and promotes proliferation, invasion and migration of

A549 cells

The aforementioned experimental results demonstrated

that knockdown of TRIP13 significantly affected the function of

NSCLC cells. In order to prove the role of TRIP13 in promoting

cancer progression more effectively, the changes in abilities of

cell apoptosis, proliferation, invasion and migration after

overexpression of TRIP3 were detected. The transfection efficiency

was determined via RT-qPCR, and it was found that TRIP13 was

significantly overexpressed (Fig.

6A). The TRIP13 overexpression group had increased cell

proliferation compared with the vector group (Fig. 6B). The Transwell assay was used for

detecting the H1299 cell migratory and invasive abilities. The

results demonstrated that these abilities were significantly

increased in the TRIP13 overexpression group compared with the

vector group (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the

wound healing experiment identified that TRIP13 overexpression

significantly promoted lateral cell migration (Fig. 7B).

In contrast to TRIP13 knockdown, TRIP13

overexpression in A549 cells consistently reduced the apoptotic

rate at 48 h after transfection (Fig.

8A). In addition, the TRIP13 overexpression group showed a

significant decrease in the number of cells in the S phase.

However, the number of cells in the G1 and G2

phase were markedly increased (Fig.

8B).

TRIP13 induces migration and invasion

via EMT in NSCLC cells

A large number of studies have reported that EMT was

an important biological process which epithelial-derived malignant

tumor cells acquire the ability to migrate and invade (23–25).

Western blotting was used to analyze the expression levels of

several EMT-related factors, such as the epithelial marker

E-cadherin and the mesenchymal markers vimentin and Snail, after

transfection (Fig. 9A). The results

demonstrated that TRIP13 knockdown could increase E-cadherin

expression and decrease vimentin and Snail expression in H1299

cells. However, TRIP13 overexpression led to the opposite results.

TRIP13 overexpression decreased the protein expression level of

E-cadherin and enhanced the protein expression levels of vimentin

and Snail (Fig. 9). The gray scale

ratio of the three proteins to the internal reference was used to

reflect the differences between each group (Fig. 9B and C).

Discussion

China has a high incidence of lung cancer, and due

to its poor prognosis, effective diagnostic criteria and treatment

options are important for patients. The present study considered

TRIP13 to be a potential biomarker worthy of further

investigation.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that TRIP13

serves a carcinogenic role in numerous cancer types. For example,

Zhang et al (26) reported

that TRIP13 silencing could suppress the function of glioblastoma

cells by regulating the expression of F-box and WD repeat domain

containing 7 (FBXW7). c-Myc is a proto-oncogene that can affect the

development of several tumor cells, and it has been shown that the

TRIP13/FBXW7/c-Myc pathway may provide a reliable target for

glioblastoma treatment. In hepatocellular carcinoma, TRIP13 was

positively correlated with actinin α 4 and activated the Akt/mTOR

pathway to accelerate the malignant progression of hepatocellular

carcinoma (27). The mitotic

checkpoint complex (MCC) coordinates with the SAC to maintain

genomic stability and inhibits the expression of certain complexes,

such as anaphase promoting complex (28). TRIP13 bound to p31comet to transform

activate closed mitotic arrest deficient 2 like 1 (MAD2) into open

MAD2, which was not active and could cause the decomposition of

MCC. TRIP13 was further shown to be a AAA+ ATPase that binds to

related proteins (29–31).

As the use of chemotherapeutic drugs has increased

in the treatment of tumors, cancer cells have become more

resistant. A previous study reported that upregulation of TRIP13

could enhance the progression of bladder cancer cells. These

authors revealed that the proliferation of tumor cells was

significantly decreased after knockdown of TRIP13. Moreover, the

apoptotic rate was also significantly reduced in these

drug-resistant cells, as shown by flow cytometry (18). To further investigate the mechanism

via which TRIP13 participates in DNA repair, the researchers

detected the expression level of H2AX phosphorylated at serine 139

(γH2AX), which is a typical marker of DNA damage, and RAD50 double

strand break repair protein (RAD50), which is a typical marker of

DNA repair. The results showed that overexpression of TRIP13 could

inhibit the expression of γH2AX and enhance the expression of RAD50

after treatment with cisplatin. Thus, these researchers suggested

that TRIP13 may promote DNA repair in tumor cells (32). Therefore, TRIP13 could be considered a

novel potential target for the diagnosis and treatment of

tumors.

In the present study, a high expression of TRIP13 in

NSCLC was identified. TRIP13 was differentially expressed in NSCLC

of different grades, based on the database results, and indicated a

poor prognosis. Furthermore, knockdown of TRIP13 in H1299 cells

increased apoptosis and inhibited proliferation, invasion and

migration. Consistently, overexpression of TRIP13 inhibited

apoptosis and promoted proliferation, invasion and migration of

A549 cells.

EMT is closely associated with the aggressive

behavior of cancer cells (33).

E-cadherin is responsible for cell adhesion and cell cytoskeleton

organization. The loss of E-cadherin is a key step in the EMT

process, leading to the transition of epithelial cells to

aggressive mesenchymal cells. It has also been confirmed that

E-cadherin promotes cell proliferation and polarization to

accelerate the metastasis of tumors (34). Moreover, changes in vimentin

expression are closely associated with the malignant progression of

tumors (35). As an important

component of the signaling pathway, Snail promotes the progression

of NSCLC (36). Previous studies have

reported that TRIP13 induced changes in the expression levels of

several EMT markers to promote the progression of several cancer

types (32,37,38).

However, there are some limitations in the present

study. It has been proved that TRIP13 could affect the metastasis

of NSCLC via EMT pathways. However, the other pathways that TRIP13

could affect metastasis are yet to be further determined. The

relationship between TRIP13 and prognosis of patients has not been

evaluated. These were the major points for the future work.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

upregulated TRIP13 could be a novel and potential biomarker for the

diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC and served an important role in

the malignant progression of NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Health Bureau of

Nantong City (grant no. WKZL2018054) and the Nantong Science and

Technology Bureau (grant no. MSZ18008).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are

available from The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset (https://cancer.gov/).

Authors' contributions

JS was devoted to the conception and design of this

study. RL and QZ performed the experiments. LJ, LC and FW analyzed

the experimental data and presented statistical results. RL, QZ and

FW collected the tissues. RL, QZ and JS wrote the manuscript. JS

contributed to revise this manuscript and approved the final

version to be published. RL, QZ and JS were responsible for

confirming the authenticity of the raw data. All authors read and

agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring

that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of

the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Third

People's Hospital of Nantong Affiliated to Nantong University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

TRIP13

|

thyroid hormone receptor-interacting

protein 13

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

IHC

|

immunohistochemistry

|

|

SAC

|

spindle assembly checkpoint

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal

transformation

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bade B and Dela Cruz C: Lung cancer 2020:

Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 41:1–24.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schuller HM: The impact of smoking and the

influence of other factors on lung cancer. Expert Rev Respir Med.

13:761–769. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rivera GA and Wakelee H: Lung cancer in

never smokers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 893:43–57. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jones GS and Baldwin DR: Recent advances

in the management of lung cancer. Clin Med (Lond). 18 (Suppl

2):S41–S46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Steven A, Fisher SA and Robinson BW:

Immunotherapy for lung cancer. Respirology. 21:821–833. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kim D, Lee YS, Kim DH and Bae SC: Lung

cancer staging and associated genetic and epigenetic events. Mol

Cells. 43:1–9. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Skřičková J, Kadlec B, Venclíček O and

Merta Z: Lung cancer. Cas Lek Cesk. 157:226–236. 2018.

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Huang J, Li B, Xue H, Tricot G, Hu

L, Xu Z, Sun X, Chang S, Gao L, et al: A small-molecule inhibitor

targeting TRIP13 suppresses multiple myeloma progression. Cancer

Res. 80:536–548. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ye Q, Rosenberg S, Moeller A, Speir J, Su

T and Corbett K: TRIP13 is a protein-remodeling AAA+ ATPase that

catalyzes MAD2 conformation switching. Elife. 4:e073672015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Clairmont CS, Sarangi P, Ponnienselvan K,

Galli LD, Csete I, Moreau L, Adelmant G, Chowdhury D, Marto JA and

D'Andrea AD: TRIP13 regulates DNA repair pathway choice through

REV7 conformational change. Nat Cell Biol. 22:87–96. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yost S, de Wolf B, Hanks S, Zachariou A,

Marcozzi C, Clarke M, de Voer R, Etemad B, Uijttewaal E, Ramsay E,

et al: Biallelic TRIP13 mutations predispose to Wilms tumor and

chromosome missegregation. Nat Genet. 49:1148–1151. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ma HT and Poon RYC: TRIP13 regulates both

the activation and inactivation of the spindle-assembly checkpoint.

Cell Rep. 14:1086–1099. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tao Y, Yang G, Yang H, Song D, Hu L, Xie

B, Wang H, Gao L, Gao M, Xu H, et al: TRIP13 impairs mitotic

checkpoint surveillance and is associated with poor prognosis in

multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 8:26718–26731. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yao J, Zhang X, Li J, Zhao D, Gao B, Zhou

H, Gao S and Zhang L: Silencing TRIP13 inhibits cell growth and

metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating of

TGF-β1/smad3. Cancer Cell Int. 18:2082018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ju L, Li X, Shao J, Lu R, Wang Y and Bian

Z: Upregulation of thyroid hormone receptor interactor 13 is

associated with human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep.

40:3794–3802. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sheng N, Yan L, Wu K, You W, Gong J, Hu L,

Tan G, Chen H and Wang Z: TRIP13 promotes tumor growth and is

associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Cell Death

Dis. 9:4022018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gao Y, Liu S, Guo Q, Zhang S, Zhao Y, Wang

H, Li T, Gong Y, Wang Y, Zhang T, et al: Increased expression of

TRIP13 drives the tumorigenesis of bladder cancer in association

with the EGFR signaling pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 15:1488–1499.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dong L, Ding H, Li Y, Xue D, Li Z, Liu Y,

Zhang T, Zhou J and Wang P: TRIP13 is a predictor for poor

prognosis and regulates cell proliferation, migration and invasion

in prostate cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 121:200–206. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang Q, Dong Y, Hao S, Tong Y, Luo Q and

Aerxiding P: The oncogenic role of TRIP13 in regulating

proliferation, invasion, and cell cycle checkpoint in NSCLC cells.

Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 12:3357–3366. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mittal V: Epithelial mesenchymal

transition in tumor metastasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 13:395–412. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pastushenko I and Blanpain C: EMT

transition states during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends

Cell Biol. 29:212–226. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yeung KT and Yang J:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Mol Oncol.

11:28–39. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Saitoh M: Involvement of partial EMT in

cancer progression. J Biochem. 164:257–264. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang G, Zhu Q, Fu G, Hou J, Hu X, Cao J,

Peng W, Wang X, Chen F and Cui H: TRIP13 promotes the cell

proliferation, migration and invasion of glioblastoma through the

FBXW7/c-MYC axis. Br J Cancer. 121:1069–1078. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhu MX, Wei CY, Zhang PF, Gao DM, Chen J,

Zhao Y, Dong SS and Liu BB: Elevated TRIP13 drives the AKT/mTOR

pathway to induce the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via

interacting with ACTN4. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:4092019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Alfieri C, Chang L, Zhang Z, Yang J,

Maslen S, Skehel M and Barford D: Molecular basis of APC/C

regulation by the spindle assembly checkpoint. Nature. 536:431–436.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Alfieri C, Chang L and Barford D:

Mechanism for remodelling of the cell cycle checkpoint protein MAD2

by the ATPase TRIP13. Nature. 559:274–278. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ye Q, Kim D, Dereli I, Rosenberg SC,

Hagemann G, Herzog F, Tóth A, Cleveland DW and Corbett KD: The AAA+

ATPase TRIP13 remodels HORMA domains through N-terminal engagement

and unfolding. EMBO J. 36:2419–2434. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lu S, Qian J, Guo M, Gu C and Yang Y:

Insights into a crucial role of TRIP13 in human cancer. Comput

Struct Biotechnol J. 17:854–861. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lu S, Guo M, Fan Z, Chen Y, Shi X, Gu C

and Yang Y: Elevated TRIP13 drives cell proliferation and drug

resistance in bladder cancer. Am J Transl Res. 11:4397–4410.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lu W and Kang Y: Epithelial-mesenchymal

plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis. Dev Cell.

49:361–374. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Venhuizen J, Jacobs F, Span P and Zegers

M: P120 and E-cadherin: Double-edged swords in tumor metastasis.

Semin Cancer Biol. 60:107–120. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Strouhalova K, Přechová M, Gandalovičová

A, Brábek J, Gregor M and Rosel D: Vimentin intermediate filaments

as potential target for cancer treatment. Cancers (Basel).

12:1842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Xie Q, Zhu Z, He Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wang

Y, Luo J, Peng T, Cheng F, Gao J, et al: A lactate-induced

Snail/STAT3 pathway drives GPR81 expression in lung cancer cells.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1866:1655762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Agarwal S, Behring M, Kim HG,

Chandrashekar DS, Chakravarthi BVSK, Gupta N, Bajpai P, Elkholy A,

Al Diffalha S, Datta PK, et al: TRIP13 promotes metastasis of

colorectal cancer regardless of p53 and microsatellite instability

status. Mol Oncol. 14:3007–3029. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kurita K, Maeda M, Mansour MA, Kokuryo T,

Uehara K, Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Hamaguchi M and Senga T: TRIP13 is

expressed in colorectal cancer and promotes cancer cell invasion.

Oncol Lett. 12:5240–5246. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|