Introduction

Hedgehog (HH) signaling is a developmentally

conserved pathway in numerous embryonic tissues and has been shown

to be dysregulated in multiple cancers (1,2). The

Sonic Hedgehog cascade involves the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) ligand

binding to Patched (PTCH), a 12-pass transmembrane protein. When

the ligand is absent, PTCH represses the activity of the

neighboring 7-pass membrane protein Smoothened (SMO). This

inhibition is released upon Shh binding. The ensuing activation of

SMO triggers a chain of events that lead to the release of GLI1-3

effector proteins from the Suppressor of Fused (SuFu) and their

subsequent translocation to the nucleus (2). The activated HH/GLI pathway has been

linked to a number of types of human cancers and causes accelerated

proliferation and survival and an enhanced rate of metastasis. HH

also supports the self-renewal of cancer stem cells (CSCs), a

subpopulation of tumor cells with inherent resistance to therapy

(3,4). HH activity can be regulated in a

noncanonical manner, and does not require the initial Shh binding

to the receptor. A number of pathways, such as RAS (5), MAPK (6), AKT (7)

and EGFR (8), have been shown to

activate GLI factors directly in tumor cells.

The HH pathway has been shown to be essential for

the oncogenic properties of melanoma (6). Moreover, blunting GLI1 and GLI2

restores sensitivity to vemurafenib in vemurafenib-resistant

melanoma cells harboring BRAF mutations (9). SOX2 is crucial for the self-renewal of

CSCs in melanoma and is regulated by GLI1 and GLI2, thus mediating

HH signaling (10). GLI1 and GLI2

also transcriptionally regulate several genes involved in positive

regulation of the cell cycle, such as E2F1, cdk1 and cyclin B

(11).

The transcription factor Slug, the protein product

of the SNAIL2 gene, belongs to the Snail family of

zinc-finger transcription factors (12). As early as 1998, the human Slug

protein was described to contain 268 amino acids and its molecular

weight is ~30 kDa (13). Slug is

expressed during embryogenesis and is critical for the development

of the neural crest (14). Notably,

Slug and Snail significantly contribute to the maintenance of CSCs

(15). Slug is an antiapoptotic

protein that contributes to the transcriptional repression of

E-cadherin in epithelial tumors, thus contributing to

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in tumor cells (16). This is achieved by upregulating the

expression of Zeb1, which is then engaged in repressing E-cadherin

(17). Furthermore, Twist1

upregulates Slug which mediates Twist1-induced changes during EMT

(18). Cooperatively, these

transcription factors repress epithelial markers, enabling cell

detachment and migration during early stages of EMT, which is a key

phenomenon underlying cancer progression and invasion (19). Moreover, increased Slug expression

is found in patients suffering from a number of types of cancers

(20). Increased Slug levels are

linked to metastasis, tumor recurrence and poor prognosis and play

a role in the maintenance of CSCs (21). The CSC-like properties of tumor

cells promote tumor initiation, expansion, EMT, metastasis, and

tumor relapse and confer resistance to chemotherapy and

radiotherapy in multiple types of cancer (22). Downregulation of Slug results in

inhibition of the proliferation of cancer cell lines, and its

overexpression leads to accelerated proliferation (21).

In melanoma, SLUG has been considered to be a

pro-oncogenic gene contributing to EMT (17). Slug expression in melanoma cells has

been reported to be regulated by osteonectin (SPARC). PI3/Akt

kinase signaling acts upstream of SPARC, as its blockade hinders

induction of the SLUG gene by SPARC, cell migration, and

EMT-like changes (23). The protein

Nodal is involved in the expression of SNAIL and SLUG

genes and activation of ALK/Smads and PI3K/AKT pathways (24,25).

Slug silencing has also been shown to increase the radiosensitivity

of melanoma cells (26).

Despite these findings, the precise mechanisms of

Slug expression and its role in EMT remain to be elucidated in

melanoma. Gupta et al (27)

described the necessity of Slug for the development of melanoma

metastases in a mouse model. By contrast, Slug protein expression

has been observed to be diminished in human metastases (28). Slug, together with Zeb2, was notably

found to be downregulated during EMT in melanoma. Slug and Zeb2

transcription factors have been reported to drive a melanocytic

differentiation program and behave as oncosuppressive proteins,

whereas Zeb1 and Twist1 repress differentiation and have oncogenic

properties (29). Similar

conclusions were reported by Gunarta et al (30) after ablating GLI1 function in

melanoma. GLI1-knockdown cells exhibited reduced invasion ability

accompanied by downregulation of the EMT factors Snail1, Zeb1 and

Twist1 but not Snail2 or Zeb2. As SLUG is one of the genes

contributing to CSC maintenance, a central question for

understanding the acquisition of the mesenchymal state and CSC

renewal is how the expression of genes involved in EMT is

regulated. In brief, inconsistent results have been reported

regarding SLUG gene function in melanoma cells, and the

mechanisms of its expression have not been extensively studied. The

present study investigated the transcriptional regulation of

SLUG in human melanoma cells and observed that Slug

expression is controlled by the HH/GLI pathway, particularly the

GLI2 transcription factor.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The present study used eight melanoma cell lines

(listed in Table SI). Their

mutational status (BRAF and NRAS mutations) is shown in Table SII. The origin of cells has been

described previously (31,32). Cells were cultivated in RPMI medium

(MilliporeSigma) supplemented with 10% FCS (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), glutamine and antibiotics (MilliporeSigma) at

37°C and 5% CO2 in 100% humidity. All cell lines were

authenticated and tested for mycoplasma using a mycoplasma

detection kit (MP0035; MilliporeSigma). Cells were passaged every

72–96 h using a trypsin-EDTA solution. When plated, cells

(5×105) were seeded from a stable culture into 12-well

plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C prior to inhibitor treatment

or transfection, unless specified otherwise. Normal human

melanocytes were purchased from Cascade Biologics Inc. and

cultivated according to the manufacturer´s instructions. The

generation of inducible melanoma cell lines in which

melanoma-associated transcription factor (MITF) protein can be

downregulated by the addition of doxycycline (Tet-on system) has

been previously described (32).

Chemical inhibitors

GANT61 (stock prepared in DMSO) and cyclopamine

(stock prepared by dissolving in ethanol) were purchased from

Selleck Chemicals LLC. The chemicals were applied to cells as

indicated in the appropriate figures for 20 h before cell

harvesting if not stated otherwise. The addition of 20 µM GANT61

for 20 h was used after the optimization of both the concentration

and time to follow the changes in expression of GLI-dependent

genes, when no signs of apoptosis had been yet detected in

cells.

Western blot analysis

To obtain whole-cell extracts for immunoblotting

analysis, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 5

mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 0.1%

SDS) with the addition of the protease and phosphatase inhibitors

aprotinin, pepstatin and leupeptin at 1 mg/ml each. cOmplete (Roche

Diagnostics) was added as recommended by the supplier. Then, 1 mM

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (MilliporeSigma) and phosphatase

inhibitor PhosSTOP (Roche Diagnostics) were added. Equal amounts of

protein (30 µg; concentration determined by Bradford's assay) were

loaded on 10–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, separated by

electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Blots were

blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk Blotto (cat. no. sc-2325, Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), and incubated with 1:1,000 diluted primary

antibodies for 2 h, washed, and then incubated at room temperature

for 1 h with 1:4,000 diluted secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (cat. no. sc-2055 or

cat. no. sc-2030; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Chemiluminescent

detection was used. For western blotting shown in Fig. 5A and B, cells were lysed in PLB

buffer (Promega Corporation), used in dual luciferase measurements

and these extracts were then directly utilized. Primary antibodies

for western blotting were: GLI1 (cat. no. 3538; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), GLI2 (cat. no. TX46056; GeneTex, Inc.), and GLI3

(cat. no. AF3690; R&D Systems, Inc.). Anti-Slug (cat. no.

sc-166476) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Klf4

(cat. no. LS-C415468) and ALDH1A1 (cat. no. LS-B10149) from LSBio.

Anti-FLAG (M2; cat. no. F1804) and anti-β-actin (A5316) antibodies

were purchased from MilliporeSigma. Anti-livin antibody (cat. no.

sc-30161) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. and MITF (D5)

antibody (cat. no. NBP2451590) was from Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc. Brn-2 (cat. no. sc-514295) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc. E- and N-cadherins, vimentin, Zeb1, and Zeb2 antibodies were

from Cell Signaling Technology (cat. no. 9782). Western blot bands

were quantified using ImageJ (v. 1.52j) software (National

Institutes of Health; data not shown).

| Figure 5.MITF is an imperfect activator of

Slug in 501mel melanoma cells. (A) Left, SLUG promoter

activity is slightly decreased by cotransfection of the MITF

expression vector and activated ~twice by the MITF-Vp16 chimeric

hyperactive MITF vector. Middle, the melastatin promoter is

activated by both the MITF and MITF-Vp16 proteins. pcDNA3 plasmid

served as a control. Three other melanoma cell lines likewise

showed nonsignificant differences in the activity of the

SLUG promoter compared with the control plasmid when

cotransfected with the MITF vector (not shown). Right, western

blotting shows MITF expression after transfection. The control

sample also has a strong MITF signal because the endogenous protein

level is already present in naive 501mel cells. (B) Left,

SLUG promoter activity after cotransfection of FLAG-tagged

versions of the same plasmids as shown in (A). Middle, stimulation

of melastatin promoter activity. Empty pFLAG-CMV-4 plasmid served

as a control. Statistical analysis was as described in Materials

and methods and verified using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post hoc test and equal results (P-values) were obtained. Right,

Western blotting performed with the anti-FLAG antibody show

expression of FLAG-tagged proteins, the same pattern of expression

was seen after the transfection of melastatin promoter (not shown).

(C) Western blots depicting inducible knockdown of MITF by

tetracycline-regulatable shRNA repressing MITF. Concomitant

expression of Slug and livin proteins was observed in the same

samples, whereas no change in Slug protein levels was observed. Six

melanoma cell lines (left panel) and two control lines (right

panel) were analyzed. Β-actin detection served as a loading control

for whole cell lysates (bottom). This figure is reprinted as a part

of Figure 3 from our previously published paper Vlčková K et

al: Inducibly decreased MITF levels do not affect proliferation

and phenotype switching but reduce differentiation of melanoma

cells (J. Cell. Mol. Med. 22, 2018, 2240-2251) (32), with the permission of the publisher

(Wiley Global Permissions, permissions@wiley.com). MITF,

melanoma-associated transcription factor. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01. |

Plasmids

The 12×GLI-TK-Luc plasmid was obtained from

Professor R Toftgard, Karolinska Institute, Sweden. pGL3-PTCH1 was

kindly donated by Professor Aberger, University of Salzburg,

Austria. The PATCHED gene promoter contains one active

GLI-binding site responsible for its activity (data not shown). The

pGL3-slug-prom-full-length promoter (−5216+112) and

pGL3-slug-prom-Δmiddle (−5216-4635, −2092+112) were cloned as

XhoI-HindIII (New England BioLabs, Inc.) inserts in

the pGL3-basic plasmid (Promega Corporation).

pGL3-slug-prom-Δproximal (−5216-2092) was cloned as the

XhoI-HindIII insert. The-4635+112 promoter was cloned

as the NheI-HindIII insert. pGL3-slug-prom-middle

(−4635-2092) was cloned as the NheI-NheI (New England

BioLabs, Inc.) insert and the pGL3-slug-proximal promoter

(−2092+112) was cloned as the NheI-HindIII insert.

Cloning of all GLI expression vectors has been described previously

(31). Briefly, original GLI1 (GL1;

cat. no. 16419), GLI2 (pCS2-MT GLI2 FL; cat. no. 17648), ΔNGLI2

(pCS2-MT GLI2 delta N; cat. no. #17649) and GLI3 (GLI3 bs-2; cat.

no. 16420) were acquired from the nonprofit plasmid repository

Addgene, Inc. Respective coding sequences were amplified by PCR and

subsequently cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector or into the

pFLAG-CMV-4 plasmid (MilliporeSigma) background to obtain

FLAG-tagged GLI proteins. The types of GLI expression plasmids were

similarly effective in promoter activation. The melastatin promoter

plasmid with the three MITF-binding sites was constructed as

previously described (33). The

construction of the short hairpin plasmid directed to MITF has been

previously described (32). All

final plasmid inserts were verified by sequencing on both strands

(GATC Biotech).

Transfection and promoter-reporter

assays

Transient cell transfections of the promoter

reporters were performed using 12-well plates at 37°C, seeded and

incubated for 24 h before transfections, and the transfection

reagent Mirus TransIT-2020 (Mirus Bio LLC) following the

manufacturer's instructions and harvested 48 h after transfection.

For detection, a dual luciferase system (Promega Corporation) was

used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The pGL3-basic

vector was used as a negative control. Expression vectors or

controls (pCDNA3 or pFLAG-CMV-4) were cotransfected together with

the reporter plasmids. Cell lysates were used for dual luciferase

assays performed as recommended by the manufacturer's instructions.

The luciferase values were acquired on a Turner Designs 20/20

luminometer (Promega Corporation). Data were normalized to

Renilla luciferase activity (internal control) as arbitrary

units. Statistical analysis of luciferase assay results was

performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test and

SigmaPlot software V10.0 (Systat Software Inc.). Where indicated,

cells were treated with GANT61 or cyclopamine 20 h at 37°C before

harvesting. Tomatidine, a compound inactive in the HH pathway but

structurally similar to cyclopamine, was tested as a negative

control and revealed similar results as vehicle (data not

shown).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol®

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

supplier´s instructions (3×105 cells per 30 mm well).

Then 2 µg of RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript IV

reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and qPCR

was performed using a TaqMan QuantiTect Probe PCR kit (Qiagen GmbH)

on a ViiA7 Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

following the manufacturer's instructions (cycling: 30 sec at 94°C

and 1 min at 60°C). Data analysis was performed by QuantStudio 6

Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Concurrent results were

obtained in three independent experiments with the following PCR

primers and probe for SLUG: Forward,

5′-AGAACTCACACGGGGGAGAAG-3′; reverse,

5′-CTCAGATTTGACCTGTCTGCAAA-3′; probe,

5′-6-FAM-TTTTTCTTGCCCTCACTGCAACAGAGC-TAMRA-3′. β-Actin was utilized

as an internal standard control: Forward, 5′-ATTGCCGACAGGATGCAGAA,

reverse, 5′-GCTGATCCACATCTGCTGGAA; probe,

6-FAM-CAAGATCATTGCTCCTCCTGAGCGCA-TAMRA. Fluorescent probes were

purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

501mel cell cultures were transfected using Mirus

TransIT-2020 (Mirus Bio LLC) with the pcDNA3-GLI1,

pcDNA3-GLI2 or pcDNA3-GLI3 expression plasmids in 90 mm plates.

After 24 h of treatment, fresh medium was applied. After another 24

h, cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room

temperature and incubated with glycine solution, and chromatin

immunoprecipitation was performed by using the ChIP-IT High

Sensitivity kit (Active Motif, Inc.) in accordance with the

manufacturer's protocols. Anti-acetylated histone H3 antibody

(MilliporeSigma) was used as the positive control, and rabbit

nonimmune IgG (MilliporeSigma) was used as a negative control. To

detect GLI1 bound to the promoter, a rabbit anti-GLI1 antibody

(cat. no. sc-20687; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used.

Rabbit anti-GLI2 (cat. no. ab26056; Abcam) was used to precipitate

GLI2. For GLI3, a rabbit anti-GLI3 antibody (cat. no. 3538; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) was used and 2 µg of each antibody was

added in each reaction. To assess the amount of ChIP-generated DNA,

PCR was performed using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The amplification of the regions

of the proximal SLUG promoter was performed with four alternative

primer pairs: Region A (−2108-1766): sense,

5′-GCATACGTGTTACTCGCTAGCAC-3′, antisense,

5′-TCCTTGTTTCACTCTACACAGTCTATTCAC-3′; region B (−1769-1163): sense,

5′-AGGAAATAATAGCCATGGCGATA-3′, antisense,

5′-CATCTCTGTCCATTGCAGAC-3′; region C (−1182-490): sense,

5′-GTCTGCAATGGACAGAGATGC-3′, antisense, 5′-GGGAAGCGGGAAGACAAAG-3′;

and region D: (−509+112): sense, 5′-CCTTTGTCTTCCCGCTTCCCCCTTCC-3′,

antisense, 5′-ACACGGCGGTCCCTACAGCATCG-3′. PCR products were

resolved on 1% agarose gels. The intensity of the final PCR bands

was quantified using ImageJ (v. 1.52j) software (National

Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence, four cell lines (501mel,

Hbl, SK-MEL-5 and SK-MEL-28) were seeded into 8-well Lab-Tek II

Chamber Slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After 48 h, 20 µM

GANT61 was added for 20 h at 37°C. Vehicle (DMSO) alone was added

to the controls. The cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde at

room temperature for 10 min, washed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton

X-100, and blocked with 5% goat serum. Slides were then stained

with Slug primary antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-166476; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) at room temperature for 2 h followed by

1:1,000 secondary anti-mouse fluorescein-coupled antibody (cat. no.

FI-2000-1.5, Vector Laboratories, Inc.) and mounted in medium with

DAPI to stain nuclei. The visualization was performed using an

Olympus IX70 microscope with cellSens software V2.2 (Olympus

Corporation).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues (skin,

nevus and melanoma) were retrieved from the archive of the

Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Second Faculty of

Medicine, Charles University, University Hospital Motol, Prague. At

least four samples of each tissue were processed and similar

results were obtained. Deparaffinized, rehydrated in descending

ethanol series, and blocked (with 3% H2O2)

sections were stained with 1:1,000 primary antibodies.

Immunohistochemistry for MITF was performed with the primary

antibody MITF (cat. no. D5; cat. no. NBP2451590, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). GLI2 was stained with antibody cat. no. GTX46056

(GeneTex, Inc.) and Slug with anti-Slug (A-7) sc-166476 antibody

(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Detection was performed using an

EnVision+ avidin-biotin detection system (Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Each tissue was examined by two pathologists.

Tissues were scored on a scale of 0 to 4 based on the combined

extent and intensity of staining. The final score represented the

predominant staining pattern of both combined parameters. Section

fields were imaged using a BX51 microscope (Olympus Corporation)

equipped with a PROMICAM 3-3CP 3.1 camera and QuickPHOTO CAMERA 3.2

software (Olympus Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance (P-values) was assessed

using a two-tailed Student's t test and Mann-Whitney test. Standard

error of the mean values are depicted in graphs as bars within each

column in the reporters and RT-qPCR. Data not significant

(P>0.05) were not labeled, values of 0.01 <P<0.05 are

marked by an asterisk, and values with P<0.01 are marked by two

asterisks. SigmaPlot software V10.0 (Systat Software Inc.) and

GraphPad Prism v.8.4.3 software (Dotmatics) were used to perform

statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was verified using

one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc tests as specified in figure

legends. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Slug expression in melanomas is

inhibited by the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor GANT61

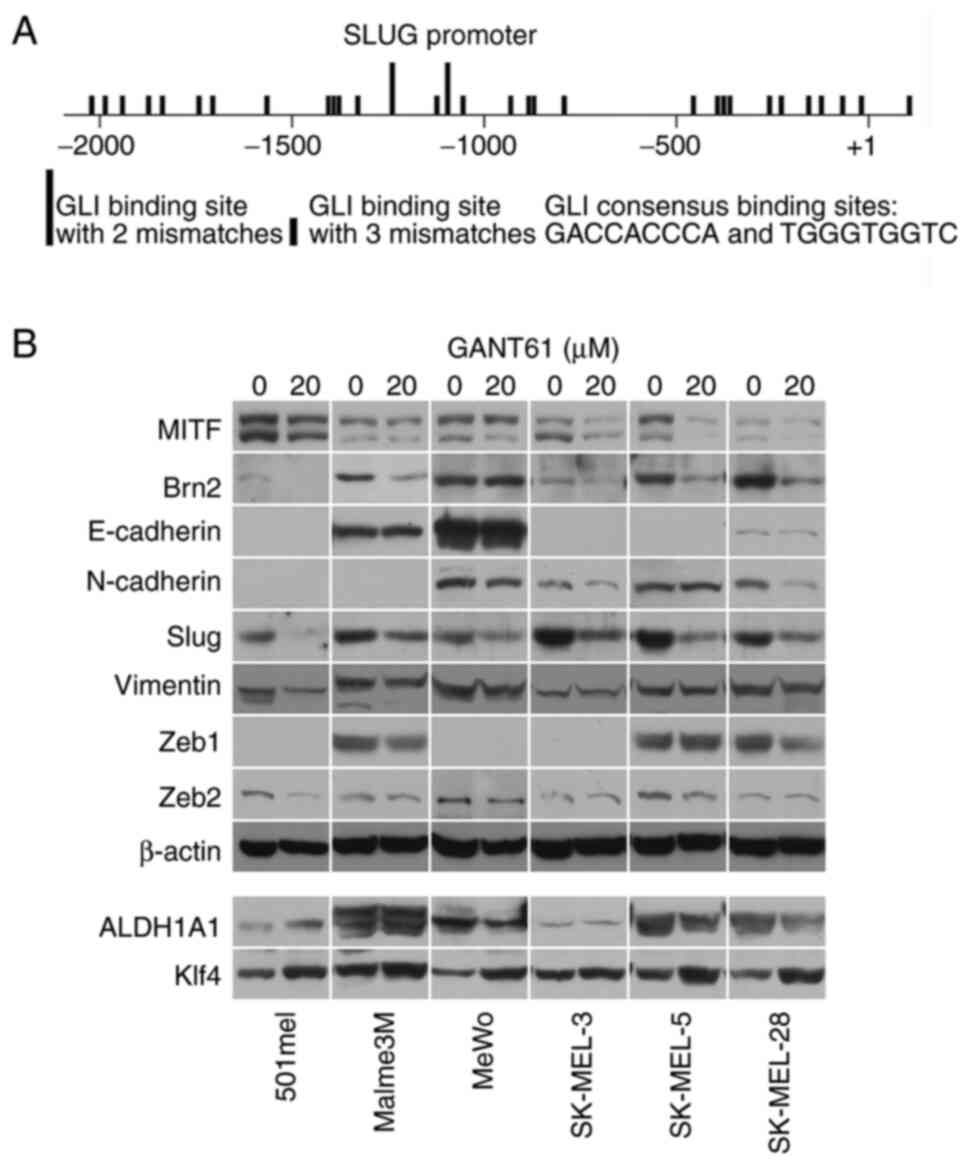

Snail1 and Snail2 (Slug) are among the main players

in the tumorigenic program of EMT (19). SLUG gene deletions have been

found in Waardenburg syndrome and piebaldism in humans (34,35),

indicating the involvement of Slug in melanin pigmentation. The

SLUG gene has long been thought to be under the

transcriptional control of MITF (34). To further explore the regulation of

Slug expression in melanoma, the present study examined the SLUG

promoter and found 85 GLI-binding sites in the long SLUG promoter

(−5216 +112; the start of translation is +1) and 31 sites in the

proximal promoter (−2092 +112; Fig.

1A and Table SIII). Although

none of the sites was a full consensus, GLI proteins, which are the

final executive factors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway, bind to

and are also active from sites with two or three mismatched

nucleotides. This implies that SLUG gene expression could be

controlled by the Hedgehog pathway.

To further investigate this hypothesis, Slug protein

expression was examined in melanoma cell lines treated with GANT61,

a potent and specific pan-GLI transcriptional inhibitor. It was

found that GANT61 decreased Slug protein in all eight melanoma cell

lines investigated as well as in normal melanocytes (Figs. 1B and SI). BRAF- or NRAS-mutated or wild-type

cells for both oncogenes were present among the analyzed melanoma

cell lines (Table SII). The levels

of other proteins known to be involved in EMT, such as E- and

N-cadherins, vimentin, Zeb1 and Zeb2, were not appreciably changed

after GANT61 treatment in six melanoma cell lines. Likewise, the

CSC markers ALDH1A1 and Klf4 were generally only slightly affected

(Fig. 1B). A mild increase in Klf4

was noted in the cell lines 501mel, MeWo, SK-MEL-5 and SK-MEL-28,

while ALDH1A1 levels were somewhat increased in 501mel cells and

slightly diminished in SK-MEL-28 cells after GANT61 treatment

(Fig. 1B). Only Brn2 (N-Oct-3,

POU3F2) protein, a known repressor of MITF (36), noticeably decreased in five of six

cell lines, suggesting that its transcription may also be regulated

by the HH pathway in most melanomas. MITF was slightly

downregulated in three cell lines (Fig.

1B). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed blunting of Slug

expression after the treatment of melanoma cells with GANT61

(Fig. S2).

SLUG promoter-reporter is activated by

GLI2 and inhibited by GANT61 and cyclopamine

Since the transcriptional inhibitor of GLI factors

GANT61 downregulated Slug protein expression, the activity of the

SLUG promoter was analyzed in reporter assays. Examination

of luciferase expression driven by the long (full-length) promoter

(−5216+112) and its truncated versions revealed that the middle

part of promoter (−4635-2092) was the most active fragment

(Fig. 2A). Its deletion greatly

decreased the activity of the full-length promoter. The short

portion most upstream (−5216-4635) probably performs an inhibitory

function because its presence in the contexts of the full-length

promoter, middle part and proximal promoter (−2092+112) decreased

the luciferase activity (Fig. 2A).

As the proximal promoter also showed appreciable activity, it was

used in the following experiments.

| Figure 2.Promoter-reporter analysis of the

SLUG gene promoter. (A) The long (full-length) SLUG

promoter (−5216+112) and its truncated versions were assayed for

activity in 501mel cells. Only two-mismatched consensus GLI-binding

sites are shown as blue bars. pGL3-basic was used as a negative

control and exhibited near zero activity (data not shown). The

statistical significance of truncated promoters is related to the

long promoter (100%). (B) Inhibition of the proximal SLUG

promoter by GANT61 and cyclopamine in three cell lines. Bars are

the mean ± standard error of the mean). The statistical

significance is related to the activity of the untreated proximal

promoter. (C) Activation of the 12×GLI-site full consensus promoter

by GLI transcription factors. Left, the control plasmid

(pGL3-basic) had extremely low activity and was negligibly

influenced by GLI factors; right, the massive effect of GLI

expression vectors on a positive control reporter plasmid with 12

full consensus GLI sites. (D) Left, inhibition of the GLI-activated

PATCHED promoter by GANT61; middle left, middle right and

right graphs, GANT61 inhibited three versions of the SLUG

promoter. The most significant inhibition was seen with the

proximal promoter (right). The GLI-mediated effect is compared with

the control (pGL3-basic) in (B-left) and (D). The significance of

GANT61-mediated inhibition is related to the vehicle-treated

control. Statistical analyses were performed using a Student´s t

test. Statistical analysis was verified using one-way ANOVA test,

followed by Dunnett's post hoc test and equal results (P-values)

were obtained. In all reporter assays, two or three independent

experiments were performed (in triplicate) with similar results,

and one representative experiment is shown. In all graphs, ±

standard error of the mean bars are shown. Statistical

significance: no mark, not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

(E) Western blotting showing similar levels of expression of all

GLI proteins in (C) and (D). GLI, GLI family zinc finger. |

Next, to test whether the SLUG promoter-reporter is

directly activated by cotransfected expression vectors for GLI

factors and inhibited by GANT61, it was first investigated whether

the proximal promoter activity decreased after the addition of HH

pathway inhibitors. Indeed, both GANT61 and cyclopamine lowered the

activity in all three melanoma cell lines tested (Fig. 2B). As a subsequent experiment, each

of the expression vectors for GLI factors (GLI1-3) were

cotransfected with the GLI-responsive promoter containing 12

canonical GLI-binding sites (12×GLI). First, it was ascertained

that there was only a minimal difference between the cotransfected

control (pcDNA3) and GLI vectors with the pGL3-basic empty control

promoter (Fig. 2C, left). By

contrast, all three GLIs greatly increased 12×GLI promoter activity

compared with the negative control plasmid pcDNA3 (Fig. 2C, right). GLI3 showed the weakest

activation of the canonical 12×GLI promoter (but still ~80-fold),

whereas the highest activation (800-fold) was achieved by ΔGLI2, a

truncated version of GLI2 in which the N-terminal repression domain

was removed (37). The activity of

the GLI factors was then tested on a known HH-responsive promoter

of the PATCHED gene, also a component of the HH pathway. The

results were similar to those obtained with the canonical promoter,

but the extent of stimulation was substantially lower, ~6-fold in

the case of the most active ΔGLI2 (Fig.

2D, first graph). Similar experiments were then conducted with

the three types of SLUG promoters, the long (full-length),

Dmiddle and proximal promoters (Fig.

2D, second, third and fourth graphs). In all cases, the DGLI2

construct again showed the best activation. In accordance with the

results in Fig. 2A, the Dmiddle

promoter exhibited the lowest overall activity. When the

PATCHED and SLUG promoters were tested, the addition

of GANT61 more or less decreased the GLI-stimulated promoter

activities (Fig. 2B and D). Western

blotting verified that all GLI proteins were similarly expressed

(Fig. 2E). These results together

indicated that SLUG promoter activity is dependent mainly on

GLI2 in reporter assays and that stimulation by GLI factors can be

inhibited by GANT61.

Slug RNA levels are diminished after

GANT61 treatment

To further evaluate the transcriptional regulation

of Slug by HH/GLI, the present study examined the effect of GANT61

on Slug RNA levels using real-time PCR. RT-PCR was performed first,

followed by qPCR. In all eight melanoma cell lines tested, 20 µM

GANT61 significantly (P<0.01) lowered the mRNA level of Slug.

This indicates that the positive effect of GLI factors on

endogenous SLUG gene expression is mediated through the

activation of transcription (Fig.

3).

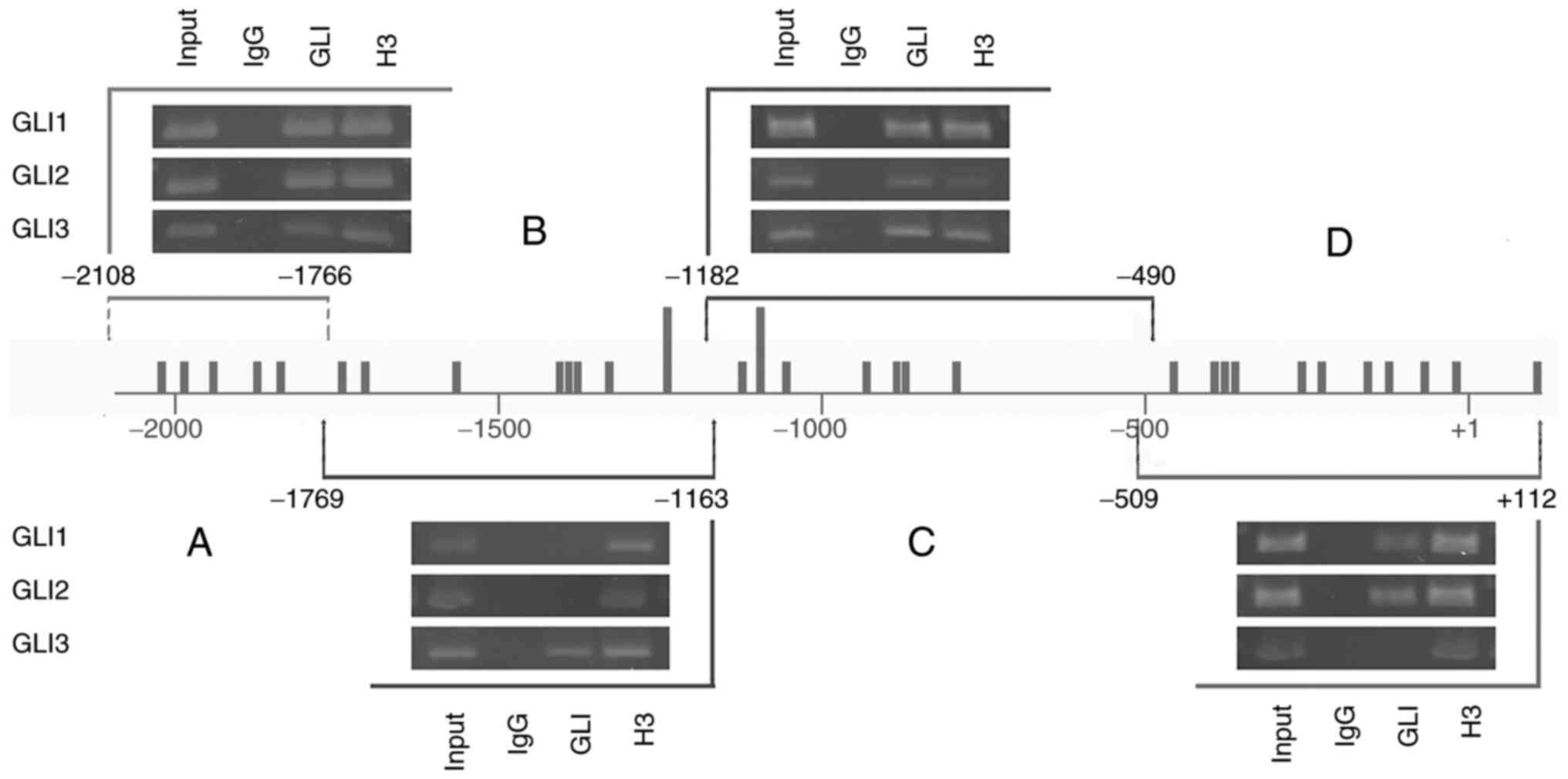

ChIP assays show binding of GLI

factors to the proximal SLUG promoter

The proximal SLUG promoter contains 31

GLI-binding sites, of which only two sites harbor two mismatches

and all other sites have three mismatches (Fig. 2A and Table SIII). To investigate whether these

sites are occupied by GLI proteins in cells, the 501mel cell line

was used to chromatin immunoprecipitate DNA fragments bound to GLIs

using specific anti-GLI1, GLI2 and GLI3 antibodies (Fig. 4). To obtain improved insight into

whether the particular GLI binds to specific regions of the

proximal promoter (−2092+112), the immunoprecipitated purified DNA

was amplified by four primer pairs (see Materials and methods) that

demarcated the four subregions A-D (Fig. 4) of the promoter. Each subregion

contained several GLI-binding sequences. The most distal region A

and a middle region C were bound by all three GLI factors. The

middle region B was remarkably occupied only by the GLI3 factor.

The most proximal fragment D was bound by GLI1 and GLI2 but not

GLI3 (Fig. 4). Thus, regions B and

D showed some preference for GLI occupancy, whereas regions A and C

clearly exhibited enrichment by all three GLI factors. Acetylated

histone H3, which was precipitated by anti-acetylated H3 antibody

as a positive control, showed occupancy at all four subregions.

Nonimmune IgG as a negative control showed no binding in any

experiment. Taken together, these data indicate that GLI

transcription factors are abundantly present at their recognition

DNA sites within the SLUG proximal promoter, further

confirming their role in the transcriptional regulation of Slug

expression through HH signaling. The data quantifying the final DNA

amount formed through PCR are in Table

SIV.

Slug is an imperfect target for MITF

in melanoma cells

The SLUG gene has been demonstrated to be

transcriptionally regulated by MITF in melanocytes (34) and during Xenopus laevis

development (38). However, data

relevant to a possible regulation of Slug expression by MITF in

melanoma cells are lacking. To test whether MITF overexpression

influences the activity of the SLUG gene promoter, we

performed promoter-reporter assays in which the proximal promoter

was cotransfected with the MITF expression construct into 501mel

cells. Additionally, we compared activation by MITF-Vp16, a

hyperactive MITF derivative in which the MITF N-terminal activation

domain (AD) was replaced by a stronger Vp16 AD (39), with native MITF. While MITF had no

effect on promoter activity, MITF-Vp16 increased it ~2-fold

(Fig. 5A left). On the other hand,

the melastatin promoter, a known MITF target (33), was stimulated by both MITF and

MITF-Vp16 ~4-fold and 10-fold, respectively (Fig. 5A middle). Western blotting verified

the total MITF protein level (the control sample also showed the

MITF protein signal because relatively high endogenous MITF protein

is already present in nontransfected 501mel cells; Fig. 5A, right). Only transfected cells

with ectopic MITF or MITF-Vp16 were measured for luciferase

activity, which explained why promoter activity increased more

compared with the overall MITF protein level. The same experiment

was repeated with the FLAG-tagged vectors, and the same results

were obtained. The expression of proteins expressed from

transfected plasmids was verified with the anti-FLAG antibody

(Fig. 5B).

To corroborate these results,

doxycycline-regulatable melanoma cell lines, in which MITF could be

downregulated by inducible expression of shRNA directed at MITF

were used (32). Whereas a decrease

in endogenous MITF protein was achieved after the addition of

doxycycline in all cell lines, Slug expression remained unchanged.

By contrast, the level of livin (ML-IAP), a known MITF target

(40), mirrored the decrease in

MITF protein (Fig. 5C). In

agreement with this, overexpression of MITF did not change the

endogenous level of Slug protein (data not shown). In a control

experiment, inducible control nontargeting shRNA revealed no

changes in the expression of all proteins tested. Thus, endogenous

Slug seems to be expressed independently of MITF protein levels in

human melanoma cells.

To further investigate the relationship between MITF

and Slug and GLI2 vs. Slug protein expression in human samples,

parallel sections of skin, nevus and melanoma metastasis were

compared by immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 6). Positive staining by anti-GLI2 and

anti-Slug antibodies was observed in the epidermis of normal skin

(scored 2–3), consistent with previous observations (41,42).

Only a few strongly MITF-positive (score 4) melanocytes were

present in the epidermis. GLI2 and Slug were also stained in nevus

cells, albeit somewhat less intensively (score 2, rare cells scored

3 in Slug staining). The nevus showed abundant MITF-positive cells

(score 4). Epidermal keratinocytes were, as expected, MITF-negative

in the skin and nevus sections (score 0). In metastatic melanoma,

both GLI2 and Slug staining was positive in ~half of the cell

population (scored 2–4), with Slug staining slightly more

positively than GLI2 staining. MITF-specific staining of metastatic

melanoma was negative (score 0), with only a small number of

positive cells (not shown in the picture). Sections that were

negative or very slightly positive for MITF (scored 0–1) showed

cells stained for both GLI2 and Slug (scores 2–3; Fig. 6). This is also consistent with the

idea that invasive and metastatic cells have low or absent MITF

(43). Notably, all three proteins

were almost exclusively localized to the nucleus. Thus, Slug

staining was associated with GLI2, but not MITF, positive staining

in immunohistochemical sections of melanomas (Fig. 6). This result supports the

aforementioned findings by demonstrating the positive regulation of

Slug expression by GLI2, but not by MITF, in melanoma cells.

Discussion

The present study described the essential role of HH

signaling and the transcription factor GLI2 in the transcription of

the SLUG gene in human melanoma cells. The large number of

GLI-binding sites present in the SLUG promoter led to the

investigation of how GLI factors regulated SLUG gene

expression. The presented data indicated that GLI factors activated

the SLUG promoter in reporter assays and that the promoter

was repressed by the HH signaling inhibitors GANT61 and

cyclopamine. The most potent activator appeared to be GLI2. All

GLI1-3 factors occupied the proximal SLUG promoter.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation data revealed abundant and specific

binding of GLI factors to four contiguous subregions of the

proximal SLUG promoter. RT-qPCR, induced decrease of MITF

and immunohistochemical experiments corroborated the foregoing

data; GANT61 diminished Slug RNA abundance, decreased MITF and did

not change Slug protein levels. In addition, the

immunohistochemical analysis showed that MIFT-negative portions of

metastatic melanomas contained Slug-positive and GLI2-positive

cells. Given that an extremely high number of GLI-binding sites are

present in the SLUG promoter, the possibility that Slug can

also be upregulated by HH in other cancer cell types is worthy of

further investigation. Of course, other transactivation mechanisms

may also be plausible in different tumors beyond melanoma. For

example, c-myb has been shown to regulate Slug expression in colon

carcinoma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and neuroblastoma cells

(44). C-myb-elicited EMT-like

characteristics through SLUG gene activation in these cells.

Homeobox C10 (HOXC10), which is a pro-oncogenic protein in cancer,

has been shown to activate the SLUG promoter in melanoma

through the YAP/TAZ signaling pathway (45). Das et al (46) reported that the oncogenic phenotype

was induced by transcriptional upregulation of osteopontin through

GLI1 in melanoma cells. Increased invasion, proliferation and

migration was relieved by HH inhibitors. On the other hand,

miR-33a-5p downregulates Slug in melanoma (47).

Previously, the essential role for HH signaling in

melanoma has been demonstrated to occur mainly through the

transcription factor GLI1 (6).

Other signaling routes, such as RAS/MAPK and Akt/mTOR, regulate the

nuclear localization of GLI1, not only in melanoma but also in

other cancer cell types (6).

Another report showed that GLI2 is capable of mediating the

invasion and metastatic properties of melanoma (48). Furthermore, Slug is considered to be

regulated by MITF, an essential transcription factor in melanoma

(34). The present study showed

that Slug expression depended mainly on the HH/GLI pathway. MITF

probably does not serve any role in the endogenous expression of

Slug because MITF downregulation had no effect on Slug protein

levels in several melanoma cell lines. In the reporter assays, only

the hyperactive MITF-Vp16 chimera, but not native MITF, activated

the SLUG gene promoter (Fig.

5A).

It has been demonstrated that the oncogene

CRKL is the downstream effector of GLI2 in lung

adenocarcinoma cells (49). Crkl,

which is oncogenic in several types of cancer, is activated by GLI2

through the binding of GLI2 to the site in the second intron of the

CRKL gene. Blunting Crkl by shRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 knockout

weakens the GLI2-elicited positive effect on cell viability,

migration, invasion and colony formation. Thus, in lung

adenocarcinoma, Crkl appears to be necessary for pro-oncogenic GLI2

effects and is itself regarded as an oncogene. For example, Crkl

attenuates the therapeutic effect of several antioncogenic drugs

(49) and has been found to be

amplified in lung adenocarcinoma (50). It remains to be investigated whether

Crkl is a general mediator of GLI factor activity in other tumor

cell types. Although CRKL has been found to be amplified

specifically in acral melanomas (51), no other data are available about the

melanoma-specific role of the Crkl protein.

HH pathway and GLI factors are highly oncogenic and

known to substantially contribute to the maintenance of CSC. In

addition, GLIs are observed to be associated with EMT in various

types of cancer (52–54). On the other hand, little data are

available that GLI factors could be directly involved in the

transcription of typical EMT-associated genes. In melanoma, GLI1

and GLI2 are reported to enhance transcription of Sox2, a stem cell

marker (10). Furthermore, it was

previously observed that EMT process is atypical in melanoma

(55), as suggested in the present

study. The present study clearly defined that GLIs, especially

GLI2, are direct transcriptional regulators of Slug, a hallmark

protein of EMT, in melanoma cells.

In melanoma, therapy is predominantly focused on

targeting the mutated driver oncogenes BRAF and NRAS and/or kinases

in the downstream MAPK signaling pathway. Unfortunately, therapies

for advanced melanoma with low molecular weight inhibitors

targeting these proteins result in acquired resistance. Despite

advances in using a combination of drugs, the concept of targeting

only the MAPK route remains questionable. As there are multiple

mechanisms responsible for resistance to the inhibition of MAPK

signaling in melanoma (56,57), alternative therapies should also be

considered. Targeting HH and Bcl2 protein by the combination of

GANT61 and obatoclax was effective in most melanoma cell lines

tested previously (58). Taken

together, the present study described a new mechanism of Slug

transcription. It stressed the importance of the HH pathway for

melanoma progression and suggested that targeting GLI2 in

combination therapies could be beneficial for treatment, as GLI2 is

a recognized transcriptional activator of a number of oncogenic

proteins, including survivin (31).

Although other mechanisms may play a role in Slug regulation in

various types of cancer, the present study demonstrated that Slug

is another HH/GLI target.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor F. Aberger (University

of Salzburg) for providing the PATCHED promoter plasmid and

Professor R. Toftgard (Karolinska Institute) for the 12×GLI

reporter plasmid.

Funding

The present study was supported by funding from the

institutional programs PROGRESQ25 and Cooperatio (research areas

SURG, MED BIOCHEM, METABOLISM, and ONCOLOGY) from Charles

University Prague, from the League against Cancer Prague, and from

the Conceptual Development of Research Organization, Motol

University Hospital, Prague, funded by the Ministry of Health,

Czech Republic (grant no. 6028). These funding organizations played

no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of this

article.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

JV and PH conceived the project. JV and PH confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. PH, JR, KK, LO, JV and PZ

performed the experiments. JB and JV Jr. performed the

immunohistochemical experiments. PH and KK performed statistical

analyses. PH and KK prepared the figures. PH and JV wrote the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Immunohistochemical analysis of paraffin sections of

human tissues was approved by the Ethical Committee of the

University Hospital Motol, Prague (approval no. EK-36/20). The

study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

Slug (Snai2, Snail2)

|

snail family zinc finger 2

|

|

Snail1

|

snail family zinc finger 1

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition

|

|

ALDH1A1

|

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member

A1

|

|

Klf4

|

Krüppel-like transcription factor

4

|

|

GLI

|

GLI family zinc finger

|

|

CSC

|

cancer stem cells

|

|

HH

|

Hedgehog signaling pathway

|

|

MITF

|

melanoma-associated transcription

factor

|

References

|

1

|

Teglund S and Toftgård R: Hedgehog beyond

medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1805:181–208. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Varjosalo M and Taipale J: Hedgehog:

Functions and mechanisms. Genes Dev. 22:2454–2472. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Marini KD, Payne BJ, Watkins DN and

Martelotto LG: Mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling in cancer. Growth

Factors. 29:221–234. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jeng KS, Chang CF and Lin SS: Sonic

Hedgehog signaling in organogenesis, tumors, and tumor

microenvironments. Int J Mol Sci. 21:7582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lauth M, Bergström A, Shimokawa T, Tostar

U, Jin Q, Fendrich V, Guerra C, Barbacid M and Toftgård R:

DYRK1B-dependent autocrine-to-paracrine shift of Hedgehog signaling

by mutant RAS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 17:718–725. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Stecca B, Mas C, Clement V, Zbinden M,

Correa R, Piguet V, Beermann F, Ruiz IA and Altaba A: Melanomas

require HEDGEHOG-GLI signaling regulated by interactions between

GLI1 and the RAS-MEK/AKT pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

104:5895–5900. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Riobó NA, Lu K, Ai X, Haines GM and

Emerson CP Jr: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt are essential for

Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:4505–4510.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mangelberger D, Kern D, Loipetzberger A,

Eberl M and Aberger F: Cooperative Hedgehog-EGFR signaling. Front

Biosci (Landmark Ed). 17:90–99. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Faião-Flores F, Alves-Fernandes DK,

Pennacchi PC, Sandri S, Vicente AL, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Vazquez

VL, Reis RM, Chauhan J, Goding CR, et al: Targeting the hedgehog

transcription factors GLI1 and GLI2 restores sensitivity to

vemurafenib-resistant human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 36:1849–1861.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Santini R, Pietrobono S, Pandolfi S,

Montagnani V, D'Amico M, Penachioni JY, Vinci MC, Borgognoni L and

Stecca B: SOX2 regulates self-renewal and tumorigenicity of human

melanoma-initiating cells. Oncogene. 33:4697–4708. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pandolfi S, Montagnani V, Lapucci A and

Stecca B: HEDGEHOG/GLI-E2F1 axis modulates iASPP expression and

function and regulates melanoma cell growth. Cell Death Differ.

22:2006–2019. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nieto MA: The snail superfamily of

zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

3:155–166. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cohen ME, Yin M, Paznekas WA, Schertzer M,

Wood S and Jabs EW: Human SLUG gene organization, expression, and

chromosome map location on 8q. Genomics. 51:468–471. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pérez-Mancera PA, González-Herrero I,

Maclean K, Turner AM, Yip MY, Sánchez-Martín M, García JL, Robledo

C, Flores T, Gutiérrez-Adán A, et al: SLUG (SNAI2) overexpression

in embryonic development. Cytogenet Genome Res. 114:24–29. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang Y, Shi J, Chai K, Ying X and Zhou BP:

The role of snail in EMT and tumorigenesis. Curr Cancer Drug

Targets. 13:963–972. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bolós V, Peinado H, Pérez-Moreno MA, Fraga

MF, Esteller M and Cano A: The transcription factor Slug represses

E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal

transitions: A comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J Cell

Sci. 116:499–451. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wels C, Joshi S, Koefinger P, Bergler H

and Schaider H: Transcriptional activation of ZEB1 by Slug leads to

cooperative regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition-like phenotype in melanoma. J Invest Dermatol.

131:1877–1885. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Casas E, Kim J, Bendesky A, Ohno-Machado

L, Wolfe CJ and Yang J: Snail2 is an essential mediator of

Twist1-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition and metastasis.

Cancer Res. 71:245–254. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Brabletz S, Schuhwerk H, Brabletz T and

Stemmler MP: Dynamic EMT: A multi-tool for tumor progression. EMBO

J. 40:e1086472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pérez-Mancera PA, González-Herrero I,

Pérez-Caro M, Gutiérrez-Cianca N, Flores T, Gutiérrez-Adán A,

Pintado B, Sánchez-Martín M and Sánchez-García I: SLUG in cancer

development. Oncogene. 24:3073–3082. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cobaleda C, Pérez-Caro M, Vicente-Dueñas C

and Sánchez-García I: Function of the zinc-finger transcription

factor SNAI2 in cancer and development. Annu Rev Genet. 41:41–61.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Barbato L, Bocchetti M, Di Biase A and

Regad T: Cancer stem cells and targeting strategies. Cells.

8:9262019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fenouille N, Tichet M, Dufies M, Pottier

A, Mogha A, Soo JK, Rocchi S, Mallavialle A, Galibert MD, Khammari

A, et al: The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulatory

factor SLUG (SNAI2) is a downstream target of SPARC and AKT in

promoting melanoma cell invasion. PLoS One. 7:e403782012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Guo Q, Ning F, Fang R, Wang HS, Zhang G,

Quan MY, Cai SH and Du J: Endogenous Nodal promotes melanoma

undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Snail and Slug in

vitro and in vivo. Am J Cancer Res. 5:2098–2112. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pearlman RL, Montes de Oca MK, Pal HC and

Afaq F: Potential therapeutic targets of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in melanoma. Cancer Lett. 391:125–140. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Arienti C, Tesei A, Carloni S, Ulivi P,

Romeo A, Ghigi G, Menghi E, Sarnelli A, Parisi E, Silvestrini R and

Zoli W: SLUG silencing increases radiosensitivity of melanoma cells

in vitro. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 36:131–139. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gupta PB, Kuperwasser C, Brunet JP,

Ramaswamy S, Kuo WL, Gray JW, Naber SP and Weinberg RA: The

melanocyte differentiation program predisposes to metastasis after

neoplastic transformation. Nat Genet. 37:1047–1054. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shirley SH, Greene VR, Duncan LM, Torres

Cabala CA, Grimm EA and Kusewitt DF: Slug expression during

melanoma progression. Am J Pathol. 180:2479–2489. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Caramel J, Papadogeorgakis E, Hill L,

Browne GJ, Richard G, Wierinckx A, Saldanha G, Osborne J,

Hutchinson P, Tse G, et al: A switch in the expression of embryonic

EMT-inducers drives the development of malignant melanoma. Cancer

Cell. 24:466–480. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gunarta IK, Li R, Nakazato R, Suzuki R,

Boldbaatar J, Suzuki T and Yoshioka K: Critical role of

glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 in maintaining invasive and

mesenchymal-like properties of melanoma cells. Cancer Sci.

108:1602–1611. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Vlčková K, Ondrušová L, Vachtenheim J,

Réda J, Dundr P, Zadinová M, Žáková P and Poučková P: Survivin, a

novel target of the Hedgehog/GLI signaling pathway in human tumor

cells. Cell Death Dis. 7:e20482016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vlčková K, Vachtenheim J, Réda J, Horák P

and Ondrušová L: Inducibly decreased MITF levels do not affect

proliferation and phenotype switching but reduce differentiation of

melanoma cells. J Cell Mol Med. 22:2240–2251. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Miller AJ, Du J, Rowan S, Hershey CL,

Widlund HR and Fisher DE: Transcriptional regulation of the

melanoma prognostic marker melastatin (TRPM1) by MITF in

melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Res. 64:509–516. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sánchez-Martín M, Rodríguez-García A,

Pérez-Losada J, Sagrera A, Read AP and Sánchez-García I: SLUG

(SNAI2) deletions in patients with Waardenburg disease. Hum Mol

Genet. 11:3231–3236. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sánchez-Martín M, Pérez-Losada J,

Rodríguez-García A, González-Sánchez B, Korf BR, Kuster W, Moss C,

Spritz RA and Sánchez-García I: Deletion of the SLUG (SNAI2) gene

results in human piebaldism. Am J Med Genet A. 122A:125–132. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Goodall J, Carreira S, Denat L, Kobi D,

Davidson I, Nuciforo P, Sturm RA, Larue L and Goding CR: Brn-2

represses microphthalmia-associated transcription factor expression

and marks a distinct subpopulation of microphthalmia-associated

transcription factor-negative melanoma cells. Cancer Res.

68:7788–7794. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Roessler E, Ermilov AN, Grange DK, Wang A,

Grachtchouk M, Dlugosz AA and Muenke M: A previously unidentified

amino-terminal domain regulates transcriptional activity of

wild-type and disease-associated human GLI2. Hum Mol Genet.

14:2181–2188. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kumasaka M, Sato S, Yajima I, Goding CR

and Yamamoto H: Regulation of melanoblast and retinal pigment

epithelium development by Xenopus laevis Mitf. Dev Dyn.

234:523–534. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Vachtenheim J and Drdová B: A dominant

negative mutant of microphthalmia transcription factor (MITF)

lacking two transactivation domains suppresses transcription

mediated by wild type MITF and a hyperactive MITF derivative.

Pigment Cell Res. 17:43–50. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dynek JN, Chan SM, Liu J, Zha J,

Fairbrother WJ and Vucic D: Microphthalmia-associated transcription

factor is a critical transcriptional regulator of melanoma

inhibitor of apoptosis in melanomas. Cancer Res. 68:3124–3132.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ikram MS, Neill GW, Regl G, Eichberger T,

Frischauf AM, Aberger F, Quinn A and Philpott M: GLI2 is expressed

in normal human epidermis and BCC and induces GLI1 expression by

binding to its promoter. J Invest Dermatol. 122:1503–1509. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Parent AE, Choi C, Caudy K, Gridley T and

Kusewitt DF: The developmental transcription factor slug is widely

expressed in tissues of adult mice. J Histochem Cytochem.

52:959–965. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Müller J, Krijgsman O, Tsoi J, Robert L,

Hugo W, Song C, Kong X, Possik PA, Cornelissen-Steijger PD, Geukes

Foppen MH, et al: Low MITF/AXL ratio predicts early resistance to

multiple targeted drugs in melanoma. Nat Commun. 5:57122014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tanno B, Sesti F, Cesi V, Bossi G,

Ferrari-Amorotti G, Bussolari R, Tirindelli D, Calabretta B and

Raschellà G: Expression of Slug is regulated by c-Myb and is

required for invasion and bone marrow homing of cancer cells of

different origin. J Biol Chem. 285:29434–29445. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Miao Y, Zhang W, Liu S, Leng X, Hu C and

Sun H: HOXC10 promotes growth and migration of melanoma by

regulating Slug to activate the YAP/TAZ signaling pathway. Discov

Oncol. 12:122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Das S, Harris LG, Metge BJ, Liu S, Riker

AI, Samant RS and Shevde LA: The hedgehog pathway transcription

factor GLI1 promotes malignant behavior of cancer cells by

up-regulating osteopontin. J Biol Chem. 284:22888–22897. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang ZR and Yang N: MiR-33a-5p inhibits

the growth and metastasis of melanoma cells by targeting SNAI2.

Neoplasma. 67:813–824. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Alexaki VI, Javelaud D, Van Kempen LC,

Mohammad KS, Dennler S, Luciani F, Hoek KS, Juàrez P, Goydos JS,

Fournier PJ, et al: GLI2-mediated melanoma invasion and metastasis.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 102:1148–1159. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liu X, Hu Y, Yu B, Peng K and Gan X: CRKL

is a critical target of Hh-GLI2 pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. J

Cell Mol Med. 25:6280–6288. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kim YH, Kwei KA, Girard L, Salari K, Kao

J, Pacyna-Gengelbach M, Wang P, Hernandez-Boussard T, Gazdar AF,

Petersen I, et al: Genomic and functional analysis identifies CRKL

as an oncogene amplified in lung cancer. Oncogene. 29:1421–1430.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Weiss JM, Hunter MV, Cruz NM, Baggiolini

A, Tagore M, Ma Y, Misale S, Marasco M, Simon-Vermot T, Campbell

NR, et al: Anatomic position determines oncogenic specificity in

melanoma. Nature. 604:354–361. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jiang L, Huang J, Hu Y, Lu P, Luo Q and

Wang L: Gli promotes tumor progression through regulating

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small-cell lung cancer. J

Cardiothorac Surg. 15:182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chun HW and Hong R: Significance of the

hedgehog pathway-associated proteins Gli-1 and Gli-2 and the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition-associated proteins Twist and

E-cadherin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 3:1753–1762.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wang L, Jin JQ, Zhou Y, Tian Z, Jablons DM

and He B: Gli is activated and promotes epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in human esophageal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget.

9:853–865. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kim JE, Leung E, Baguley BC and Finlay GJ:

Heterogeneity of expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

markers in melanocytes and melanoma cell lines. Front Oncol.

4:972013.

|

|

56

|

Davies MA and Kopetz S: Overcoming

resistance to MAPK pathway inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst.

105:9–10. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Vachtenheim J and Ondrušová L: Many

distinct ways lead to drug resistance in BRAF- and NRAS-mutated

melanomas. Life (Basel). 11:4242021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Vlčková K, Réda J, Ondrušová L, Krayem M,

Ghanem G and Vachtenheim J: GLI inhibitor GANT61 kills melanoma

cells and acts in synergy with obatoclax. Int J Oncol. 49:953–960.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|