Introduction

Periodontal abscesses have a high prevalence rate

and are thus considered to be the third most prevalent infection

which demands emergency treatment (1,2).

Clinically, periodontal abscess usually presents as an ovoid

swelling in the gingiva along the lateral side of the root

(3,4). It is usually associated with a

periodontal pocket, the presence of bleeding upon probing and

suppuration, and the involved tooth may exhibit increased tooth

mobility and tenderness upon percussion (1,5).

Periodontal abscesses are treated with oral rinses, mechanical

debridement and drainage; antibiotic therapy is only administered

in certain conditions, such as endo-perio lesions, phoenix abscess,

etc (2).

Based on the etiology, periodontal abscesses can be

either periodontitis-related or non-periodontitis-related. Occlusal

trauma has been shown to be linked to periodontal abscesses

(4,5). Occlusal trauma is the damage

inflicted to teeth when excessive force acts upon the tooth. It is

basically the injury resulting in tissue changes within the

attachment apparatus as a result of occlusal force. Excessive

occlusal forces applied to a tooth with normal periodontal support

is termed as primary occlusal trauma, and when the injury results

from excessive forces on tooth/teeth with reduced periodontal

support, this is considered as secondary occlusal trauma (6).

Occlusal trauma is considered to elicit an

inflammatory response in the periodontal apparatus, as well as in

the dental pulp, which can lead to pulpal death, and the

derangement in periodontal structures and alveolar bone (7).

Both periodontal and endodontic disorders can

advance at different rates, depending on a variety of factors, such

as injuries, trauma, etc (4,6).

These elements may also have an impact on the effectiveness of any

given treatment. The additional impact of treating one tissue on

the companion tissue should be taken into account when treating

teeth with concurrent endodontic and periodontal disorders. The

timing of endodontic therapy is a crucial factor to consider when

scheduling treatment for concurrent periodontal and endodontic

disorders. Furthermore, since cross-seeding through the apical or

lateral foramina is a possibility, the result of endodontic therapy

may be affected if the root canal filling is inserted, while a

periodontal infection that interacts with the root canal system is

still present. Fortunately, utilizing an antibacterial medication

inside the canals during periodontal therapy helps keep the

environment within the root canal system in a state that is

unfavorable for bacterial colonization, particularly if the

dressing is changed on a frequent basis. Utilizing a biocompatible

medication is crucial for encouraging periodontal recuperation and

for improving the general outlook of the tooth (7).

The present study describes the inter-disciplinary

management involving endodontic and periodontal treatment of the

tooth of a patient with periodontal abscess due to occlusal

trauma.

Case report

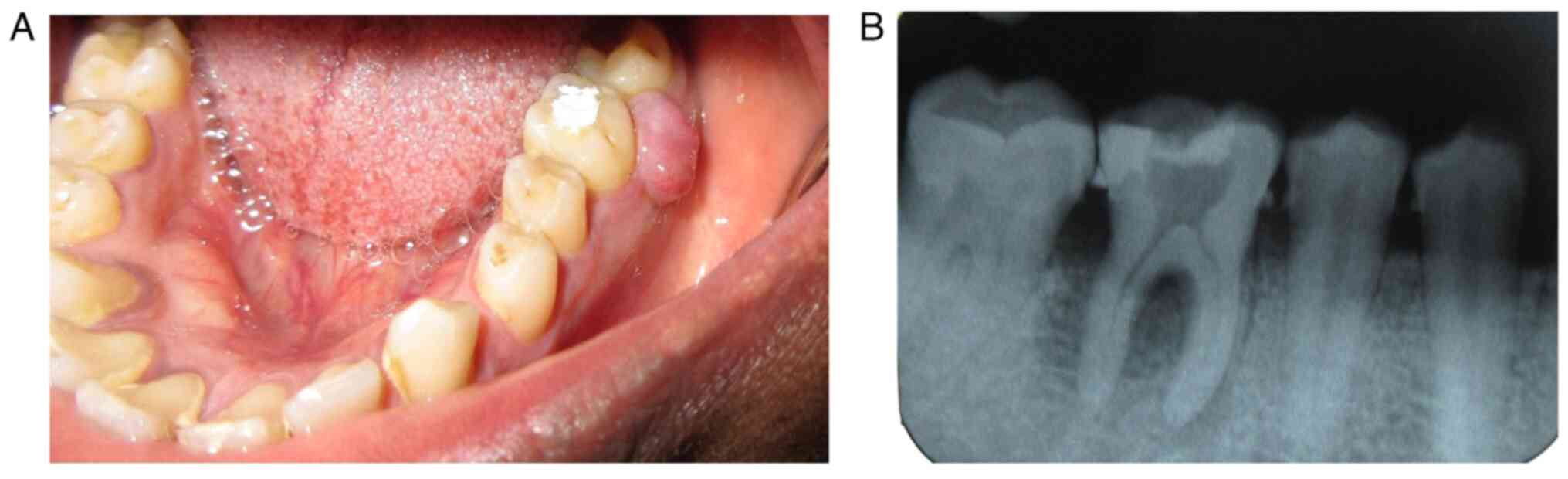

A 42-year-old male patient reported to the

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics (Manipal

College of Dental Sciences Mangalore, Manipal Academy of Higher

Education, Manipal, India) with the chief complaint of a fractured

cusp with respect to the lower left back tooth, 1 week prior. The

medical history of the patient was non-contributory and the

biochemical parameters were not evaluated. No extraoral changes

were noted, and an intraoral examination revealed a bilateral

fractured cusp on tooth no. 36, which was found to be due to

excessive masticatory load. Pulp sensibility tests revealed that

the tooth was vital. No periapical changes were noted on intraoral

periapical radiograph. Taking into consideration the clinical and

radiographic findings, a composite restoration was performed to

build up the fractured cusp after relieving the tooth from

occlusion.

Following this episode, the patient returned to the

aforementioned department after 2 months, with the complaint of a

swelling in the lower back tooth. Upon an intraoral examination, a

localized swelling (1 cm in diameter) was found on tooth no. 36. A

periodontal pocket measuring 5 mm was found on the distal aspect of

tooth no. 36. The tooth developed grade II mobility and was

rendered non-vital due to the lack of a response on the pulp

vitality test. An intra oral periapical radiograph with respect to

tooth no. 36 revealed diffuse radiolucency involving the distal

root, the loss of lamina dura in that area and radiolucency in the

furcation area, suggestive of furcation involvement. Horizontal

bone loss was also noted. Noting the aforementioned results, the

treatment strategy was planned accordingly.

Treatment of the periodontal

abscess

For the treatment of the periodontal abscess, the

patient was referred to the Department of Periodontology in the

same institution. As there was a periodontal pocket and drainage

was feasible via the sulcus, surgical drainage and incision did not

constitute the recommended course of treatment. After administering

local anesthesia, gracey curettes 11-12 and 13-14 were used to

drain the abscess through the sulcus. Following the drainage,

antibiotics (C. Amox LB, 500 mg, 1-1-1 for 5 days) were prescribed

over the course of 5 days. Additionally, urgent endodontic therapy

was initiated. Rubber dam isolation was difficult, since the tooth

was grade II mobile (Fig. 1).

By the next visit, the resolution of the swelling

was noted and the mobility had reduced from grade II to grade I. A

reduction in the depth of the periodontal pocket was observed. The

endodontic treatment was then completed using Protaper files

(Dentsply Inc., Maillefer, Dentsply India) with the crown down

technique till F2 file size. Copious irrigation was performed using

normal saline 0.9 and 5% sodium hypochlorite (Vishal Dentocare Pvt.

Ltd.). In addition, three rounds of calcium hydroxide were

administered as an intracanal medicament in the form of Calcicur

(Voco) at every 15-day intervals. After 45 days, tooth no. 36 was

obturated with an F2 protaper gutta percha cone (Dentsply Inc.,

Maillefer, Dentsply India) along with AH Plus sealer (Dentsply

Inc., Sirona, Dentsply India).

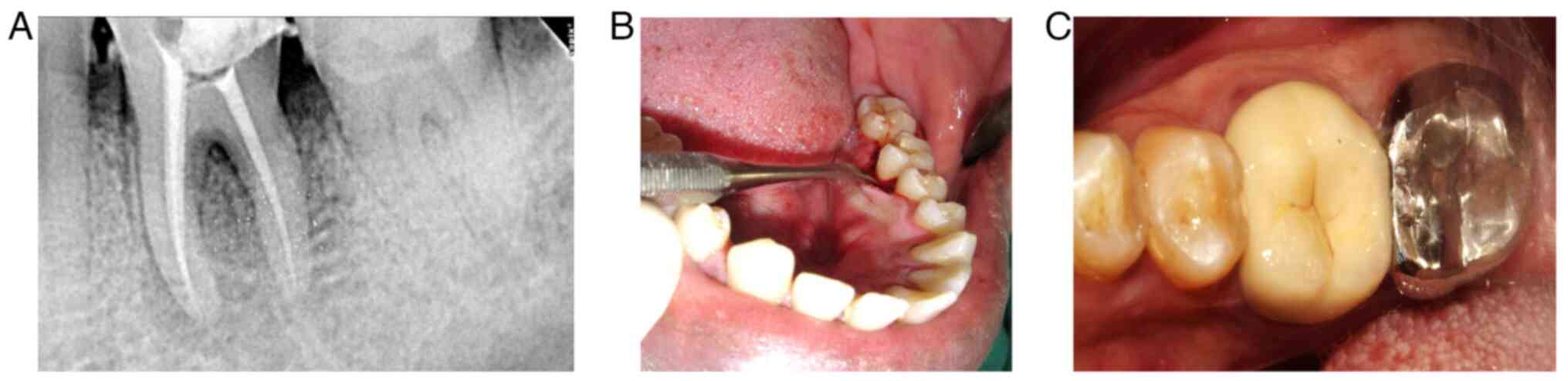

To receive the core build up, the existing

restoration was removed. Limited access to the tooth surface was

noted on the lingual side, and hence, an access flap was planned.

After administering local anesthesia, sulcular incisions was placed

around tooth no. 36, the flap was reflected using periosteal

elevator and access was achieved for the restoration. Lingually,

the access flap was reflected below the gingival margin, and the

tooth surface was smoothened using polishing bur and the entire

cavity was sealed using glass ionomer (GC Glass Ionomer Universal

Restorative) restoration (Fig.

2A). Simple interrupted sutures were placed and post-operative

instructions were provided. The patient was recalled after 1 week,

and suture removal followed by the reduction of glass ionomer

restoration and the composite core build up (Filtek Z 350 XT, 3M

ESPE) were performed. The patient was recalled after 1 month and

porcelain fused to metal crown was administered as the

post-endodontic restoration (Fig.

2B and C).

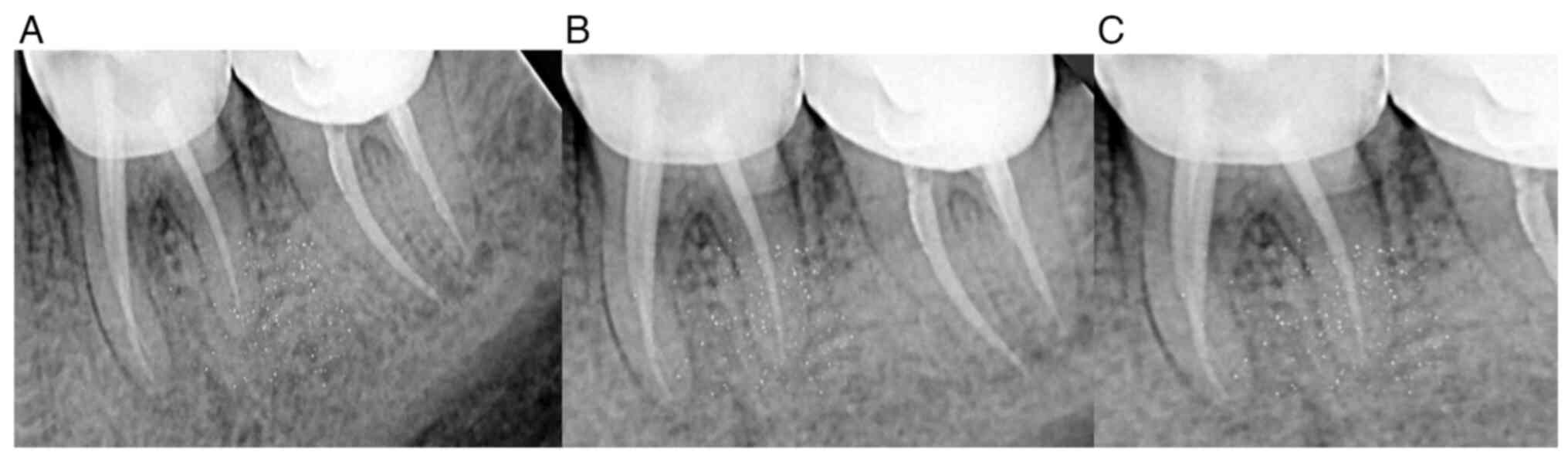

Follow-up visits were scheduled for clinical and

radiographic examinations. During the follow-up clinical

examinations, healthy gingival and periodontal health was noted

with the reduced mobility of tooth no. 36. Upon a radiographic

examination, the dissolution of periapical changes and bone fill

were noted. The patient was followed-up for 3 months, 6 months, 1

year and 2 years post-treatment (Fig.

3).

Discussion

The present study highlights the need of an

interdisciplinary approach in the management of endodontic and

periodontal lesions. The endo-periodontal conditions require the

assistance of experts from the fields of endodontic and

periodontics, as the need for periodontal therapy and endodontic

treatment cannot be accomplished by general dentists.

There are several potential causes of dental

infections, including gingival infections, trauma, surgery,

pericoronitis and pulp necrosis. Depending on the etiology of the

infection, odontogenic or dental abscesses are classified as

endodontic or periapical, periodontal, or pericoronal (3). In emergency dentistry clinics, the

frequency of periodontal abscesses has been investigated (8,9).

Periodontal abscesses are frequently linked to areas where there

was no previous periodontal pocket or directly to periodontitis.

While such occurrences can sometimes occur in the absence of an

abscess, a periodontal abscess in periodontitis indicates an

interval of ongoing bone deterioration (exacerbation). Abscesses

can emerge more easily in convoluted areas with cul-de-sacs that

ultimately become sequestered. Through the course of illness, a

periodontal abscess can arise at numerous stages: As an acute

aggravation of unresolved periodontitis during periodontal therapy,

in cases of resistant periodontitis, or while performing

periodontal management. In the absence of periodontitis,

periodontal abscesses may originate from the following causes: i)

Effects of foreign bodies; ii) an endodontic tool creating a hole

in the tooth wall; iii) the involvement of the lateral cysts; and

iv) local elements influencing the shape of the root may make a

periodontal abscess more likely to develop (3,9).

The periodontal abscess may have commenced as a

result of germs entering the soft tissue pocket wall. Chemotactic

proteins secreted by the bacteria subsequently draw in

pro-inflammatory cells, and the ensuing inflammatory response

causes the connective tissues to be destroyed, the bacterial

encapsulation and pus generation. Histologically, a core region of

damaged leukocytes and soft tissue debris is surrounded by intact

neutrophils (9).

At a later stage, neutrophils and macrophages

assemble to form a pyogenic membrane. Since a highly acidic

atmosphere will encourage the action of lysosomal enzymes, the

degree of breakdown in the abscess will be dependent on the

pathogenicity and development of the bacteria inside the foci as

well as the local pH (3).

In the case in the present study, the initial

representation was of a fractured cusp, which was found to be the

result of occlusal trauma. Occlusal trauma has long been known to

cause damage to the underlying periodontium. The injury that thus

results in the periodontium is known as trauma from occlusion. This

trauma from occlusion, when it occurs on a healthy periodontium due

to excessive occlusal forces, is known as primary trauma from

occlusion. This is known to occur when a person bites onto a hard

food substance or as a result of a faulty restoration. Secondary

trauma from occlusion on the other hand occurs in situations where

the periodontium is weak and unable to bear the normal forces of

occlusion (10). In the present

case, the periodontium was healthy and hence, the fractured cusp

may have been due to primary trauma from occlusion. Thus, occlusal

correction followed by the restoration of the cusp was

performed.

Persistent trauma has been known to cause changes in

the periapical region, causing pulp necrosis and leading to acute

periapical abscess or phoenix abscess. In the case presented

herein, the tooth was found to be mobile and an isolated deep

periodontal pocket was found to be associated with the tooth

(7,11). The pulpal infection could have

spread via the lateral canals into the periodontal pocket and lead

to a periodontal abscess (12).

Taking the clinical course and manifestations into consideration,

the case was diagnosed as an endodontic periodontal lesion.

Periodontal abscess drainage followed by endodontic treatment and

the restoration of the involved tooth were carried out.

Therefore, it is critical for a dentist to

recognize, evaluate and treat endodontic periodontal diseases in

this manner. A periodontal abscess is diagnosed according to the

symptoms experienced by the individual, as well as the signs

discovered during the oral examination. In order to improve the

prognosis of patients, the management of periodontal abscess

requires the use of therapeutic modalities carried out under expert

supervision. In the case this condition is left untreated, bacteria

will then accumulate due to the periodontal pocket closure

preventing the gingival crevicular fluid from being cleared.

However, the expulsion of the lysosomal enzymes from hosts

neutrophils is mostly responsible for tissue destruction in

periodontal abscesses. Long standing untreated cases of periodontal

abscess affects the prognosis of the condition, resulting in damage

to the periodontal architecture and osseous framework, resulting in

the exfoliation of teeth.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

RM and SP conceptualized the study. SH substantially

contributed to data interpretation, and RM, SP wrote and prepared

the draft of the manuscript. RM, SP and SH confirm the authenticity

of the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Ethics Committee Manipal College of Dental Sciences (18115),

Mangalore, India. The patient provided consent for his

participation in the study.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided consent for the publication of

the present case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors’ information

The ORCID IDs of the authors are as follows: RM

(0000-0003-3407-8685), SP (0000-0003-4512-0252) and SH

(0000-0003-0730-0914).

References

|

1

|

Corbet EF: Diagnosis of acute periodontal

lesions. Periodontol 2000. 34:204–216. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Jaramillo A, Arce RM, Herrera D,

Betancourth M, Botero JE and Contreras A: Clinical and

microbiological characterization of periodontal abscesses. J Clin

Periodontol. 32:1213–1218. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Herrera D, Roldan S and Sanz M: The

periodontal abscess: A review. J Clin Periodontol. 27:377–386.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Herrera D, Roldán S, González I and Sanz

M: The periodontal abscess (I). Clinical and microbiological

findings. J Clin Periodontol. 27:387–394. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Carranza FJ (ed): Carranza's Clinical

Periodontology. 9th edition. Saunders, Philadelphia, PH, pp448-451,

2002.

|

|

6

|

Neff P: Trauma from occlusion: Restorative

concerns. Dent Clin North Am. 39:335–354. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hallmon WW: Occlusal trauma: Effect and

impact on the periodontium. Ann Periodontol. 4:102–108.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Herrera D, Alonso B, de Arriba L, Santa

Cruz I, Serrano C and Sanz M: Acute periodontal lesions.

Periodontol 2000. 65:149–177. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Vályi P and Gorzó I: Periodontal abscess:

Etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Fogorv Sz. 97:151–155.

2004.PubMed/NCBI(In Hungarian).

|

|

10

|

Davies SJ, Gray RJ, Linden GJ and James

JA: Occlusal consideration in periodontics. Br Dent J. 191:597–604.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yegin Z, Ileri Z, Tosun G and Sener Y:

Treatment of periodontal abscess caused by occlusal trauma: A case

report. J Pediatr Dent. 1:50–52. 2013.

|

|

12

|

Serio FG and Hawley CE: Periodontal trauma

and mobility. Diagnosis and treatment planning. Dent Clin North Am.

43:37–44. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|