Introduction

Cerebral palsy is defined as a group of permanent

disorders of movement and posture development due to

non-progressive brain damage during the fetal period or early

childhood, thus causing limitations in activity. Motor disorders in

cerebral palsy are often accompanied by sensory, perceptual,

cognitive, communication, behavioral, epilepsy and secondary

musculoskeletal issues (1). The

global prevalence of cerebral palsy is 1.5-3/1,000 live births,

with spastic cerebral palsy being the most common type, accounting

for 72-80% of recorded cases (2-5).

In Vietnam, it is estimated that ~500,000 individuals live with

cerebral palsy, equivalent to 30-40% of the total disabilities in

children (6). Cerebral palsy is

the most common physical disability in children, often associated

with lifelong multiple disabilities, rendering it a significant

psychological and economic burden for families and societies

worldwide (5).

Due to multiple disabilities, children with cerebral

palsy require rehabilitation across various domains, although in

particular, they require physical therapy, occupational therapy and

speech therapy (5,7). Goal-oriented therapy methods designed

based on motor learning theory and neural plasticity, which train

tasks that are useful for daily life, have proven to be effective

for children with cerebral palsy. Evidence-based practice is

recommended for clinicians to use instead of traditional treatment

methods (8).

The Goal Attainment Scale (GAS), Gross Motor

Function Measure 66 (GMFM 66) and Pediatric Evaluation of

Disability Inventory (PEDI) are widely recognized tools for

assessing functional outcomes in pediatric populations,

particularly in children with motor impairments. GAS is a

patient-centered measure that evaluates individualized goal

achievement, offering a personalized perspective on therapy

outcomes (9-11).

The GMFM 66 quantitatively assesses changes in gross motor

function, particularly in children with cerebral palsy, providing a

reliable measure of motor performance improvements (7). The PEDI evaluates functional

capabilities and performance in daily activities, capturing a

comprehensive view of the independence of a child and caregiver

assistance needs (12,13). These tools collectively provide a

robust framework for assessing the multidimensional impact of

interventions.

Globally, a comprehensive intervention model for

children with cerebral palsy has been established. With a

family-centered approach, clinicians have collaborated to provide

evidence-based practices that meet the diverse treatment needs of

the children (14). In Vietnam,

early detection and early intervention for young children aged

<6 years with disabilities have been identified as key

components of rehabilitation and community-based rehabilitation in

recent years (15). Research has

demonstrated the effectiveness of interventions based on motor

learning theory and neuroplasticity for children with cerebral

palsy (16). During development,

the brains of children exhibit greater neuroplasticity potential

compared with more mature brains, providing enhanced opportunities

for therapeutic interventions (17). The Vietnam Ministry of Health has

incorporated the requirements of the comprehensive rehabilitation

model into the practice philosophy to guide the organization of the

model and improve rehabilitation services for children with

cerebral palsy (7,18-20).

However, early intervention and comprehensive intervention models

for young children with disabilities remain sporadically organized

(15). Studies on cerebral palsy

primarily focus on epidemiological and clinical characteristics or

report outcomes of single rehabilitation methods rather than

studying the effectiveness of a comprehensive goal-oriented and

family-centered rehabilitation model (6,21).

The successful implementation of a comprehensive, goal-directed,

family-centered rehabilitation model for children aged <6 years

with spastic cerebral palsy represents a significant advancement in

both the theory and clinical practice of rehabilitation in Vietnam.

This model has the potential for broad application across

rehabilitation centers nationwide. Therefore, the present study

aimed to fill the current gap by evaluating the simultaneous

effectiveness of interventions in the three main rehabilitation

areas: i) Physical therapy; ii) occupational therapy; and iii)

speech therapy.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present study was a prospective, non-randomized

cohort study using a comprehensive intervention model developed as

part of a rehabilitation training program provided by Humanity and

Inclusion at Hanoi Rehabilitation Hospital (Hanoi, Vietnam) from

January, 2019 to December, 2022.

Study subjects

Participants were children aged <6 years, who

were diagnosed with spastic cerebral palsy and who received

treatment at the Department of Pediatrics of Hanoi Rehabilitation

Hospital. The inclusion criteria for the present study included a

confirmed diagnosis of spastic cerebral palsy according to the

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Vietnam

Ministry of Health guidelines, characterized by motor and postural

disorders due to non-progressive brain damage that occurred before,

during or after birth with increased muscle tone and tendon

reflexes in affected limbs or signs of pyramidal tract damage

(1,18,22,23).

Participants were also required to be in level II, III or IV of the

Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS), level II, III

or IV of the Manual Ability Classification System (MACS; Mini MACS)

and level II, III or IV of the Communication Function

Classification System (CFCS). The GMFCS classifies gross motor

function, focusing on what children with cerebral palsy can achieve

within their living and activity environments (24). The MACS (for ages 4-18 years) and

Mini-MACS (for ages 1-4 years) classify the ability of children

with cerebral palsy to use their hands to manipulate objects in

daily activities (25). The CFCS

categorizes children with cerebral palsy into 5 levels based on

their daily communication abilities, considering 3 factors: i) The

ability to receive and send messages; ii) the pace of communication

with familiar or unfamiliar individuals; and iii) communication

methods such as speech, sound, eye gaze, facial expressions,

gestures, symbols, books, communication boards or assistive devices

(25). Children with hearing

impairment or vision loss and those who either discontinued or

failed to comply with treatment protocols were excluded from the

present study. Participation was voluntary and written informed

consent from the children's guardians was obtained.

Ethical considerations

The present study was approved by The Ethics

Committee of Hanoi Medical University (approval no: 60/HĐĐĐHYHN;

Hanoi, Vietnam). The present study was conducted with the voluntary

consent of the participants' guardians and research subjects could

withdraw from the present study at any stage. All information

obtained was used solely for research purposes.

Measurement of outcomes

GAS (9-11,18).

The GAS is a 5-level goal scale in which a score of -2 represents

the condition of the child at the start of the intervention and a

score of 0 corresponds to the expected outcome after the

intervention. The interpretation of each level is presented in

Table I.

| Table IGAS scoring. |

Table I

GAS scoring.

| GAS score | Levels of

achievement |

|---|

| -2 | Much less than

expected outcome |

| -1 | Less than expected

outcome |

| 0 | Expected outcome

after intervention |

| +1 | More than expected

outcome |

| +2 | Much more than

expected outcome |

GMFM 66(7)

The GMFM 66 measures gross motor function in

children with cerebral palsy and includes 66 items covering five

domains: i) Lying and rolling (four items); ii) sitting (15 items);

iii) crawling and kneeling (10 items); iv) standing (13 items); and

v) walking, running and jumping (24 items). The GMFM 66 reference

percentile was analyzed from a normal sample of 650 children with

cerebral palsy (24). Higher GMFM

scores indicate greater motor abilities and improved functional

performance.

PEDI (12,13)

The PEDI measures the performance of a child in

everyday activities, administering two parts of the rating scale

including functional skills (FS) and caregiver assistance (CA), and

assessed the following 3 areas: i) Self-care; ii) mobility; and

iii) social function. The PEDI was completed by interviewing the

primary caregiver of the child. The raw score was calculated and

transformed into a scale score. Higher scores reflect greater

independence and reduced need for caregiver assistance, showing

improvement in daily living activities and overall functional

skills.

Comprehensive, goal-oriented and

family-centered rehabilitation model

The development of the model consisted of the

following four steps:

Step 1: Orienting goals based on the needs of the

family: Upon admitting a child with cerebral palsy to the hospital,

the family of the child was provided with information about

cerebral palsy, the treatment model and evidence-based practices

that were suitable for the child and available at the hospital.

Subsequently, the family underwent an in-depth interview with a

clinician, which focused on discussions between the clinician and

the family to understand their goals and expectations when bringing

the child to the hospital. Following the interview, the clinician

helped the family to prioritize these goals for the treatment plan.

After which, the clinician performed the PEDI and collaborated with

the family to establish the intervention goals.

Step 2: Setting GAS goals based on a consensus

between clinicians and the family: Clinicians carried out necessary

evaluations to support the establishment of specific GAS goals.

After these assessments, the clinicians formulated the GAS goals

and discussed the assessment results with the family. This step

involved an agreement with the family to ensure that the GAS goals

align with their expectations and the needs of the child.

Step 3: Planning and conducting the intervention: An

intervention plan detailing training activities, time allocated for

these activities and the roles of clinicians and family in the

intervention was developed. The clinicians performed therapy

sessions with the child at the hospital and guided the family on

conducting the exercises at home.

Step 4: Post-intervention evaluation: Following the

intervention, the clinicians and the family evaluated the

achievement of the GAS goals together. The clinicians then

reassessed the child and provided the family with detailed feedback

on the assessment results and progress.

Key members of the clinician team included a

rehabilitation doctor, physical therapist, occupational therapist

and speech therapist. Additional members, such as a pediatrician or

orthodontist, would be included depending on the condition of the

child. The rehabilitation doctor acted as the team leader,

overseeing all information related to the child, performing the

PEDI by interviewing the primary caregiver of the child, orienting

the intervention goals with the family and re-evaluating the

achievement of the GAS goals after the intervention. Team members

exchanged information on a weekly basis throughout the

implementation process.

Intervention

Children received therapy at the hospital 5

days/week, 3 weeks/month for 6 months. Each session lasted 1.5 h

and included physical therapy (30 min), occupational therapy (30

min) and speech therapy (30 min).

Physical therapy focused on improving gross motor

skills and mobility. Occupational therapy aimed to enhance fine

motor skills and self-care abilities. Speech therapy was targeted

at developing communication and social skills. Goal-directed

therapy techniques were applied, which involved practicing specific

activities based on goals co-designed with the patient. Based on

the principles of motor learning and neuroplasticity, this therapy

emphasizes active and repetitive practice of tasks in real-life

environments or similar simulated settings. Individualized speech

therapy complements this by focusing on developing early

communication skills and enhancing the ability to understand and

express language.

Caregivers carried out at-home exercises according

to the guidance of clinicians, and children were encouraged to

involve themselves in the targeted activities as much as possible.

The length of home exercises varied based on the number and content

of intervention goals. Physical therapy typically lasted 30-60

min/day as guided by the physical therapist. Occupational therapy

included simulated play activities with encouragement to engage in

targeted activities, and speech therapy focused on achieving

intervention goals during daily communication activities.

Data collection

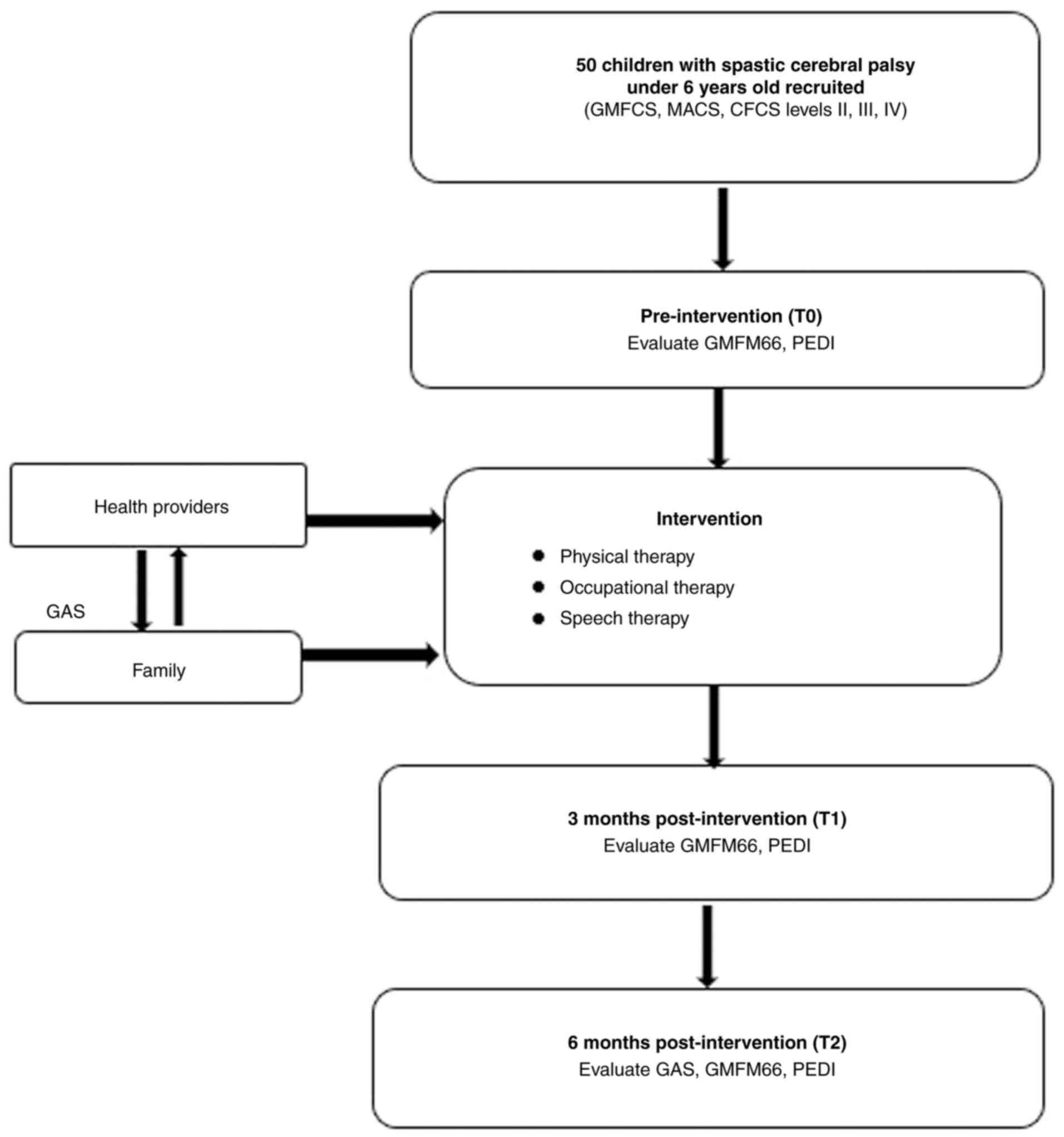

The research process is presented in Fig. 1. Children with cerebral palsy who

met the inclusion criteria underwent a comprehensive clinical

examination. This included interviewing their parents or primary

caregivers to gather information on the medical history and

condition of the child following the research case report template.

GMFCS, MACS/MiniMACS and CFCS levels were also assessed.

The PEDI and GMFM 66 scale were assessed at three

time points: i) Before the intervention (T0); ii) after 3 months

(T1); and iii) after 6 months (T2). The GAS scale criteria,

established by the clinicians, were evaluated after 6 months, with

the goal achievement results assessed in collaboration with the

families of the children with cerebral palsy (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis were performed using STATA

15.0 software (StataCorp LLC). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to

test for normality. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the

differences in intervention results between T0, T1 and T2, followed

by Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction. Spearman's rank

correlation test was used to analyze the correlation between

variables. Linear regression was used to identify factors related

to treatment outcomes. P≤0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the

50 children participating in the present study are presented in

Table II. Among these children,

60% had spastic quadriplegia, 26% had spastic hemiplegia and 14%

had spastic diplegia. The boy-to-girl ratio was 1.94:1, with boys

accounting for 66% of the participants. The average age of the

participants was 39.34 months, with the highest percentage (50%)

being 24-47 months.

| Table IICharacteristics of the study

participants (n=50). |

Table II

Characteristics of the study

participants (n=50).

| | Site of

paralysis | |

|---|

| Characteristics | Quadriplegia, n

(%) | Hemiplegia, n

(%) | Diplegia, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|

| Sex | | | | |

|

Boys | 21 (70.0) | 7 (53.9) | 5 (71.4) | 33 (66.0) |

|

Girls | 9 (30.0) | 6 (46.2) | 2 (28.6) | 17 (34.0) |

| Age | | | | |

|

≤23

months | 7 (23.4) | 2 (15.4) | 0 | 9 (18.0) |

|

24-47

months | 13 (43.3) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (42.9) | 25 (50.0) |

|

48-71

months | 10 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (57.1) | 16 (32.0) |

| GMFCS | | | | |

|

II | 4 (13.4) | 10 (76.9) | 3 (42.9) | 17 (34.0) |

|

III | 13 (43.3) | 3 (23.1) | 4 (57.1) | 20 (40.0) |

|

IV | 13 (43.3) | 0 | 0 | 13 (26.0) |

| Mini MACS | | | | |

|

II | 1 (3.3) | 8 (76.9) | 7 (100.0) | 16 (32.0) |

|

III | 18 (60.0) | 5 (23.1) | 0 | 23 (46.0) |

|

IV | 11 (36.7) | 0 | 0 | 11 (22.0) |

| CFCS | | | | |

|

II | 4 (13.3) | 4 (30.7) | 6 (86.7) | 14 (28.0) |

|

III | 11 (36.7) | 8 (61.5) | 1 (14.3) | 20 (40.0) |

|

IV | 15 (50.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 16 (32.0) |

As regards gross motor function, 34% of the children

were classified as GMFCS level II, 40% as level III and 26% as

level IV. Notably, 43.3% of the children with quadriplegia were in

GMFCS level IV, while none of the children with spastic diplegia or

hemiplegia were at this level.

The MACS (Mini MACS) evaluation of hand use revealed

that 32% of the children were in level II, 46% in level III and 22%

in level IV. No children with hemiplegia were categorized in level

IV and 100% of those with diplegia were at MACS level II.

As regards communication function, 28% had CFCS

level II, 40% had level III and 32% had level IV. Among those with

quadriplegia, 50% were at CFCS level IV, while 61.5% of children

with hemiplegia were at level III and 86.7% of spastic diplegia

cases were at level II (Table

II).

A total of 522 GAS goals were established for

physical therapy and occupational therapy over the 6-month period

of rehabilitation. The achievement rate for physical therapy goals

(levels 0, 1 and 2) was 81.3%, while the achievement rate for

occupational therapy goals was 82.7%. The combined achievement rate

for physical and occupational therapy goals was 100%. As regards

speech therapy, 249 GAS goals were established and 74.7% of the

children achieved the goals (Table

III).

| Table IIIResults of achieving GAS goals in

physical therapy and occupational therapy after 6 months of

rehabilitation. |

Table III

Results of achieving GAS goals in

physical therapy and occupational therapy after 6 months of

rehabilitation.

| | GAS score |

|---|

| Area | -2 n, (%) | -1 n, (%) | 0 n, (%) | 1 n, (%) | 2 n, (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|

| Physical

therapy | 15 (5.6) | 35 (13.1) | 120 (44.9) | 61 (22.9) | 36 (13.5) | 267(100) |

| Occupational

therapy | 8 (3.3) | 34 (14.0) | 114 (46.9) | 51 (21.0) | 36 (14.8) | 243(100) |

| Physical and

occupational | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6(50) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (8.3) | 12(100) |

| Speech therapy | 18 (7.2) | 45 (18.1) | 95 (38.2) | 58 (23.3) | 33 (13.2) | 249(100) |

The treatment results after 3 months and 6 months of

intervention are presented in Table

IV. The GMFM 66 score increased by 4.9 points at T1 (P=0.09)

and 9.9 points at T2 (P<0.001). The GMFM 66 reference percentile

rose by 17.1 points and 31.1 points after 3 and 6 months,

respectively. Increases of 5.6 points (T1) and 11.0 points (T2)

were observed in the PEDI FS mobility. The PEDI CA mobility was

improved by 7.0 and 12.9 points at T1 and T2, respectively. The

PEDI FS self-care exhibited a gain of 4.7 points following 3 months

of rehabilitation and 8.8 points after 6 months. PEDI CA self-care

increased by 7.2 points at the 3-month assessment and 13.0 points

at 6 months. All differences observed were statistically

significant (P≤0.05). Similarly, the PEDI FS social function

increased by 5.7 points at T1 and 11.1 points at T2. These

improvements were statistically significant. The PEDI CA social

function also showed significant gains, increasing by 7.9 points

after 3 months and 14.8 points after 6 months (P≤0.01).

| Table IVResults of the intervention

(n=50). |

Table IV

Results of the intervention

(n=50).

| | T0 (mean ± SD) | T1 (mean ± SD) | T2 (mean ± SD) | Pairwise

comparison | Mean

difference | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| GMFM 66 | 44.7±12.9 | 49.7±13.9 | 54.7±14.6 | T1-T0 | 4.9 | 4.5-5.3 | 0.09 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 9.9 | 9.3-10.6 | <0.001 |

| GMFM 66 reference

percentile | 43.52±31.0 | 60.60±33.4 | 74.60±29.0 | T1-T0 | 17.1 | 14.5-19.7 | 0.008 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 31.1 | 26.2-35.9 | <0.001 |

| PEDI FS

mobility | 41.4±11.7 | 47.1±12.4 | 52.5±13.0 | T1-T0 | 5.6 | 5.3-5.9 | 0.04 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 11.0 | 10.5-11.6 | <0.001 |

| PEDI CA

mobility | 37.9±12.3 | 44.9±12.2 | 50.8 ±13.1 | T1-T0 | 7.0 | 6.4-7.5 | 0.01 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 12.9 | 12.2-13.5 | <0.001 |

| PEDI FS

self-care | 39.2±10.4 | 43.9±11.0 | 48.0±11.8 | T1-T0 | 4.7 | 4.5-5.0 | 0.05 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 8.8 | 8.0-9.6 | 0.03 |

| PEDI CA

self-care | 31.0±14.1 | 38.2±13.5 | 44.0±13.4 | T1-T0 | 7.2 | 6.7-7.7 | <0.001 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 13.0 | 12.3-13.8 | <0.001 |

| PEDI FS social

function | 40.5±9.2 | 46.2±9.7 | 51.6±10.5 | T1-T0 | 5.7 | 5.4-6.0 | 0.01 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 11.1 | 10.4-11.8 | <0.001 |

| PEDI CA social

function | 34.3±12.0 | 42.2±11.6 | 49.1±11.8 | T1-T0 | 7.9 | 7.3-8.4 | 0.006 |

| | | | | T2-T0 | 14.8 | 14.0-15.6 | <0.001 |

The results of the multivariable linear regression

model underscored that the site of paralysis and GMFCS levels are

significant predictors of GMFM 66 score improvements, whereas sex,

age and other classifications are insignificantly associated with

the outcome (Table V). Compared

with children with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy, those with

hemiplegia showed a significantly greater improvement in GMFM 66

scores (Coef.=1.45; P=0.03). GMFCS levels also significantly

affected GMFM 66 score improvement. In comparison with children

classified as GMFCS level II, those at GMFCS level III presented a

1.37-point lower improvement in GMFM 66 scores (P=0.01), while

children at GMFCS level IV had a 3.97-point lower improvement

(P<0.001).

| Table VAssociation between age, sex, site of

paralysis, GMFCS level, MACS level and CFCS level, and the

improvement in GMFM 66 scores after six months of

rehabilitation. |

Table V

Association between age, sex, site of

paralysis, GMFCS level, MACS level and CFCS level, and the

improvement in GMFM 66 scores after six months of

rehabilitation.

| Parameters | Coef. | P-value | 95% CI | |

|---|

| Age, months | 0.02 | 0.28 | -0.01 | 0.05 |

| Sex (in reference

to boys) | | | | |

|

Girls | 0.04 | 0.91 | -0.77 | 0.86 |

| Site of paralysis

(in reference to quadriplegia) | | | | |

|

Hemiplegia | 1.45 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 2.72 |

|

Diplegia | 0.59 | 0.52 | -1.22 | 2.40 |

| GMFCS levels (in

reference to level II) | | | | |

|

Level

III | -1.37 | 0.01 | -2.35 | -0.39 |

|

Level

IV | -3.97 | <0.001 | -5.41 | -2.53 |

| MACS levels (in

reference to level II) | | | | |

|

Level

III | -0.47 | 0.47 | -1.75 | 0.82 |

|

Level

IV | -0.23 | 0.78 | -1.88 | 1.42 |

| CFCS levels (in

reference to level II) | | | | |

|

Level

III | 0.24 | 0.65 | -0.82 | 1.31 |

|

Level

IV | 0.44 | 0.50 | -0.88 | 1.76 |

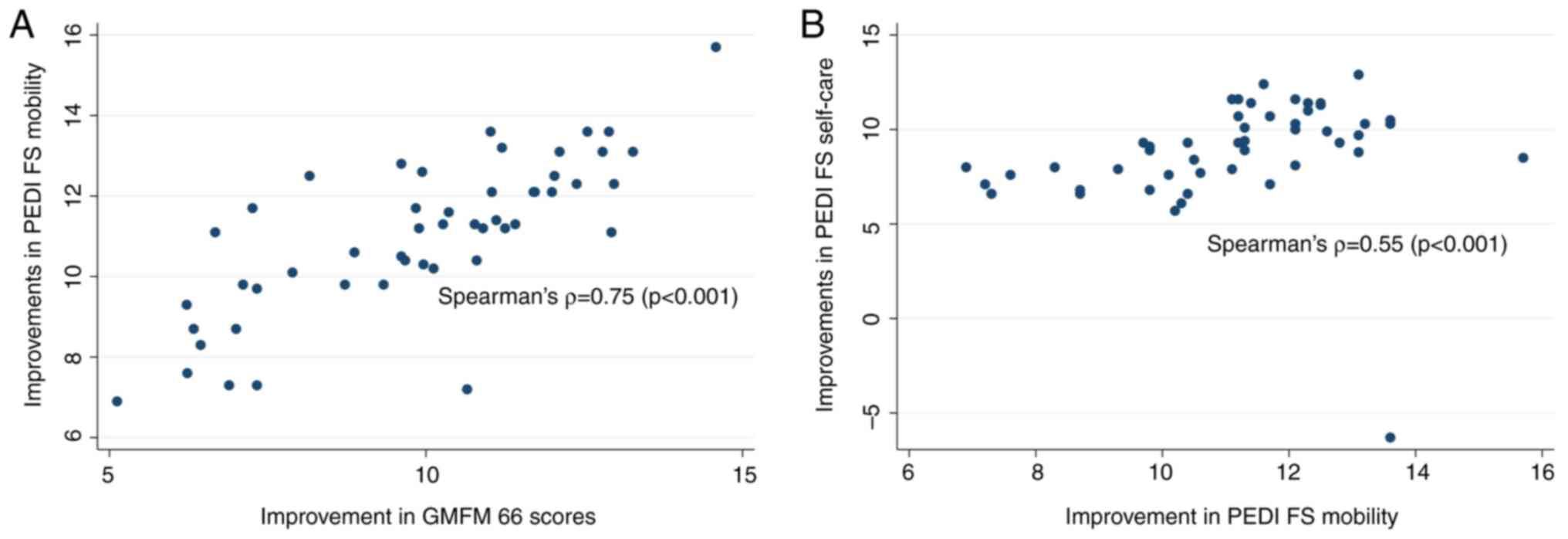

There was a strong positive correlation between the

improvement in GMFM 66 scores and the improvement in PEDI FS

mobility scores after 6 months of rehabilitation (P<0.001),

suggesting the improvement of PEDI FS mobility scores as GMFM 66

scores increased. Additionally, there was a moderate positive

correlation (r=0.55) between the improvement in PEDI FS mobility

scores and PEDI FS self-care scores (P<0.001), implying that

improvements in mobility skills are associated with enhancements in

self-care abilities (Fig. 2).

Discussion

As regards physical therapy and occupational

therapy, the results of achieving GAS goals in the present study

were similar to the results presented in the study by Storvold and

Jahnsen (27) (82.86%) and Lowing

et al (26) (84.55%) in

terms of mobility and self-care goals. In the present study,

several goals of coordination between physical therapy and

occupational therapy were established. The role of teamwork in the

rehabilitation process for children with cerebral palsy has been

promoted to achieve the desired goals of the child and family. To

ensure the validity and reliability of the GAS, all healthcare

staff who directly interacted with the children had >1 year of

experience and were trained in a GAS goal setting. Therapists

worked with families to establish GAS goals, while rehabilitation

doctors evaluated standard scales and collaborated with families to

assess the achievement of these goals.

An intensive intervention program (>3

sessions/week), including goal-directed therapy, has been shown to

effectively improve gross motor function in children with cerebral

palsy (27-31).

The GMFM 66 results from the present study are lower than the study

by Storvold and Jahnsen (27)

where a 6-week, 5 days/week and 10 h/week, intervention at the

rehabilitation center combined with home and school exercises

increased GMFM 66 scores by 10.79 points for children with GMFCS

levels I and II (27). Similarly,

Sorsdahl et al (32)

reported a 4.5-point increase after a 3-week, 5 days/week and 3

h/day intervention for children with GMFCS levels I-IV (32). These differences may be attributed

to variations in participant selection and intervention intensity,

as the present study selected children with more severe GMFCS

(levels II, III and IV) and possibly lower intervention dosage

compared with the other studies. By contrast, Lowing et al

(26) reported an increase of 5.02

points after 3 months of intervention for 22 children with GMFCS

levels I-IV, and are higher compared with the study by Ahl et

al (30) who found a

3.13-point increase after 5 months of goal-directed therapy for 14

children with GMFCS levels II-V (26,30).

In both studies, children exercised at the center once/week and the

remainder of the time at home.

Overall, studies on goal-directed therapy show that

children with cerebral palsy were all actively engaged in treatment

>3 times/week. The specific intervention dosage and whether the

intervention is conducted by healthcare professionals or the

primary caregivers of the child with cerebral palsy may vary

depending on the study. The results of these studies demonstrate

that children with cerebral palsy exhibit improvements following

intervention. However, the level of progress appears to be

influenced by the treatment dosage. Higher dosage treatments, such

as in the studies by Storvold and Jahnsen (27) and Sorsdahl et al (32) are more likely to record improved

progress. Additionally, the GMFCS level may also be related to

treatment effectiveness.

In studies on the effectiveness of goal-directed

therapy and comparing GMFM 66 scores, studies without control

groups also use the GMFM 66 reference percentile. The GMFM 66

reference percentile helps to assess the relative motor ability of

the study subjects compared with children with cerebral palsy of

the same age and GMFCS level. An increase in the GMFM 66 reference

percentile score following intervention indicates that the child

has made significant progress in gross motor function following the

intervention, as their progress surpasses that of the standard

sample. In the present study, at T1 and T2, all children showed an

increase in the GMFM 66 reference percentile scores compared with

T0. Additionally, after 3 months of intervention, the reference

percentile scores increased by an average of 17.1 points, and after

6 months, they increased by 31.1 points. The present study results

are consistent with Lowing et al (26) where the GMFM 66 reference

percentile score increased by 18 points after 3 months, and

Storvold and Jahnsen (27) in

which the GMFM 66 reference percentile scores increased from 15 to

37 points after 6 weeks.

The results of the present study are similar to

those of the study by Sorsdahl et al (32) who found that the GMFM 66 score of

children with cerebral palsy GMFCS levels I and II improved more

than levels III, IV and V after 3 weeks of intervention. However,

the current results are different from Lowing et al

(26) which reported that after 3

months of rehabilitation, the gross motor ability of children with

cerebral palsy improved but did not correlate to the level of

GMFCS. Considering the site of paralysis, the present findings are

also similar to the research results of Storvold and Jahnsen

(27) where children with spastic

quadriplegia showed less improvement in GMFM 66 scores compared

with children with spastic hemiparesis.

The improvement of the PEDI FS mobility scores in

the present study is similar to the results of the study by Lowing

et al (26), which reported

an increase of 5.85 points in PEDI FS mobility after 3 months of

intervention. However, the improvement in PEDI CA mobility was 9.4

points, higher than the results of the present study.

The improvement of the PEDI FS self-care of children

with cerebral palsy in the present study is similar to the research

results of Ahl et al (30)

and Lowing et al (26)

after 3 months, however, they reported a higher level of

improvement in the PEDI level of assistance in self-care skills, at

10.99 points. These differences may be because in Vietnam, families

typically help children with cerebral palsy more in mobility and

self-care activities.

While the GMFM 66 measures gross motor function, it

does not capture how these abilities translate into functional

mobility in daily life, such as moving on a bed, using a

wheelchair, navigating indoors or moving outdoors (28). Therefore, to evaluate the

effectiveness of goal-directed therapy, where goals are tied to

specific and practical daily activities, researchers often combine

the GMFM 66, PEDI mobility domain and the GAS scores (27,32).

By combining different assessment tools, a comprehensive

understanding of the motor and mobility capabilities of the child

in the therapy room, at home and in the community can be assessed,

thus providing a holistic evaluation of the effectiveness of

goal-directed therapy for children with cerebral palsy.

Han et al (33) found a strong correlation (r=0.83)

between the GMFM 66 and PEDI FS mobility scores in children with

spastic cerebral palsy aged 1-6 years, which aligns with the

findings of the present study (33). In the present study, a greater

improvement in GMFM-66 scores was associated with higher

improvement in PEDI FS mobility.

Improvements in PEDI FS mobility and PEDI FS

self-care are positively correlated (r=0.55; P<0.001). This

result indicates that in a rehabilitation model combining physical

and occupational therapy, children with cerebral palsy tend to make

simultaneous progress in both mobility and self-care skills.

As regards speech therapy, 249 GAS goals were

established and 74.7% of the children achieved the goals. The PEDI

FS social function and PEDI CA social function in the present study

at the 3-month mark improved more than the research results of

Sorsdahl et al (32),

Lowing et al (26) and Ahl

et al (30). This may be

because the participants in the present study received

goal-directed physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech

therapy simultaneously.

The findings of the present study have some

implications for clinical practice and future research.

Rehabilitation centers should implement a comprehensive,

goal-directed and family-centered rehabilitation model for children

with cerebral palsy. Additionally, further research is required to

assess how family training programs affect the knowledge, attitudes

and practices of guardians. Based on these evaluations, treatment

programs can be developed to enhance the duration of home-based

practice while reducing the time spent in hospital-based

therapy.

The results of the present study should be

considered in light of several limitations. First, a control group

or pre-intervention follow-up were not included, which means that

the natural progression of functional development over time could

not be entirely ruled out as a factor influencing the observed

improvements in children with cerebral palsy. In addition, the

study did not comprehensively assess co-existing health issues,

such as intellectual disabilities and speech difficulties, which

could affect the ability of children to learn motor skills and

communicate effectively. Another limitation is that the present

study mainly evaluated the functional improvement of children with

cerebral palsy after intervention in each area, and thus the

association between the effectiveness of intervention methods in

the comprehensive intervention model has not been analyzed

in-depth. It should also be noted that implementing a comprehensive

intervention model requires time and resources, such as developing

an information system on cerebral palsy to provide to families and

creating tools to simulate real-life activities. Rehabilitation

centers in Vietnam are still facing a shortage of personnel,

especially in the areas of occupational therapy and speech therapy

(19,20). Therefore, it is essential to

strengthen workforce training, conduct workshops and expand the

model.

In conclusion, the comprehensive, goal-directed and

family-centered rehabilitation model is effective for children

<6 years old with spastic cerebral palsy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KCH and VMP conceived and designed the study,

performed statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, were

involved in the investigative aspects of the study, and wrote,

reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. KCH and VMP confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by The Ethics

Committee of Hanoi Medical University (approval no.: 60/HĐĐĐHYHN;

Hanoi, Vietnam). The research was conducted with the voluntary

consent of the participants' guardians. Research subjects could

withdraw from the study at any stage and all information obtained

was used solely for research purposes.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A,

Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, Dan B and Jacobsson B: A report: The

definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med

Child Neurol Suppl. 109:8–14. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chauhan A and Singh M, Jaiswal N, Agarwal

A, Sahu JK and Singh M: Prevalence of cerebral palsy in Indian

Children: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Pediatr.

86:1124–1130. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

McManus V, Guillem P, Surman G and Cans C:

SCPE work, standardization and definition-an overview of the

activities of SCPE: A collaboration of european CP registers.

Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 8:261–265. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sellier E, Platt MJ, Andersen GL,

Krägeloh-Mann I, De La Cruz J and Cans C: Surveillance of Cerebral

Palsy Network. Decreasing prevalence in cerebral palsy: A

Multi-site European population-based study, 1980 to 2003. Dev Med

Child Neurol. 58:85–92. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Liptak GS and Accardo PJ: Health and

social outcomes of children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr. 145 (2

Suppl):S36–S41. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Khandaker G, Van Bang N, Dung TQ, Giang

NTH, Chau CM, Van Anh NT, Van Thuong N, Badawi N and Elliott EJ:

Protocol for hospital based-surveillance of cerebral palsy (CP) in

Hanoi using the paediatric active enhanced disease surveillance

mechanism (PAEDS-Vietnam): A study towards developing

Hospital-based disease surveillance in Vietnam. BMJ Open.

7(e017742)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Department of Medical Service

Administration: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Functional

Rehabilitation for Children with Cerebral Palsy-Guidelines on

Physical Therapy. J 2018.

|

|

8

|

Novak I, McIntyre S, Morgan C, Campbell L,

Dark L, Morton N, Stumbles E, Wilson SA and Goldsmith S: A

systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral

palsy: State of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol. 55:885–910.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Goal Attainment Scaling: Applications,

Theory, and Measurement. Psychology Press, New York, 2014.

|

|

10

|

Hurn J, Kneebone I and Cropley M: Goal

setting as an outcome measure: A systematic review. Clin Rehabil.

20:756–772. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Turner-Stokes L: Goal attainment scaling

(GAS) in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Clin Rehabil.

23:362–370. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Berg M, Jahnsen R, Froslie KF and Hussain

A: Reliability of the pediatric evaluation of disability inventory

(PEDI). Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 24:61–77. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Berg MM, Dolva AS, Kleiven J and

Krumlinde-Sundholm L: Normative scores for the pediatric evaluation

of disability inventory in norway. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr.

36:131–143. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Schwabe AL: Comprehensive care in cerebral

palsy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 31:1–13. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Department of Medical Service

Administration: Guidelines for Early Detection-Early Intervention

for Children's Disabilities. J 2023.

|

|

16

|

Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M,

Finch-Edmondson M, Galea C, Hines A, Langdon K, Namara MM, Paton

MC, Popat H, et al: State of the evidence traffic lights 2019:

systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating

children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.

20(3)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Johnston MV: Plasticity in the developing

brain: Implications for rehabilitation. Dev Disabil Res Rev.

15:94–101. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Department of Medical Service

Administration: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Functional

Rehabilitation for Children with Cerebral Palsy. General

Guidelines. J 2018.

|

|

19

|

Department of Medical Service

Administration: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Functional

Rehabilitation for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Guidelines on

Occupational Therapy. J 2018.

|

|

20

|

Department of Medical Service

Administration: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Functional

Rehabilitation for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Guidelines on

Speech Therapy. J 2020.

|

|

21

|

Pham VM, Hoang TL, Hoang KC, Nguyen NM,

DeLuca SC and Coker-Bolt P: The effect of constraint-induced

movement therapy for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy in

Vietnam. Disabil Rehabil. 47:912–918. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wallace SJ: Epilepsy in cerebral palsy.

Dev Med Child Neurol. 43:713–717. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence: Cerebral palsy in under 25s: Assessment and management

(NG62). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng62.

|

|

24

|

Hanna SE, Bartlett DJ, Rivard LM and

Russell DJ: Reference curves for the Gross Motor Function Measure:

Percentiles for clinical description and tracking over time among

children with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 88:596–607.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Rösblad

B, Beckung E, Arner M, Ohrvall AM and Rosenbaum P: The manual

ability classification system (MACS) for children with cerebral

palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability.

Dev Med Child Neurol. 48:549–554. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lowing K, Bexelius A and Brogren Carlberg

E: Activity focused and goal directed therapy for children with

cerebral palsy-do goals make a difference? Disabil Rehabil.

31:1808–1816. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Storvold GV and Jahnsen R: Intensive motor

skills training program combining group and individual sessions for

children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 22:150–159.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Rahlin M, Duncan B, Howe CL and Pottinger

HL: How does the intensity of physical therapy affect the Gross

Motor Function Measure (GMFM-66) total score in children with

cerebral palsy? A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open.

10(e036630)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Arpino C, Vescio MF, De Luca A and

Curatolo P: Efficacy of intensive versus nonintensive physiotherapy

in children with cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis. Int J Rehabil

Res. 33:165–171. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ahl LE, Johansson E, Granat T and Carlberg

EB: Functional therapy for children with cerebral palsy: An

ecological approach. Dev Med Child Neurol. 47:613–619.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bower E and McLellan DL: Effect of

increased exposure to physiotherapy on skill acquisition of

children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 34:25–39.

1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sorsdahl AB, Moe-Nilssen R, Kaale HK,

Rieber J and Strand LI: Change in basic motor abilities, quality of

movement and everyday activities following intensive,

goal-directed, activity-focused physiotherapy in a group setting

for children with cerebral palsy. BMC Pediatr.

10(26)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Han T, Gray N, Vasquez MM, Zou LP, Shen K

and Duncan B: Comparison of the GMFM-66 and the PEDI Functional

Skills Mobility domain in a group of Chinese children with cerebral

palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 37:398–403. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|