Introduction

A number of studies have indicated that mushrooms

are rich sources of bioactive compounds. Among them, Ganoderma

lucidum is a polypore mushroom that grows on the lower trunks

of deciduous trees. This mushroom is a traditional Oriental

medicine that has been widely used as a tonic to promote longevity

and health for thousands of years in Asian countries, including

China, Japan and Korea (1–4). The pharmacological activities of

G. lucidum, particularly its intrinsic immunomodulating and

antitumor properties, have been well-documented (4,5).

Several studies have demonstrated that various G. lucidum

extracts interfere with cell cycle progression, induce apoptosis

and suppress angiogenesis in human cancer cells and thus act as

anticancer agents (6–11). Additionally, it has also been

suggested that G. lucidum extracts have a neuroprotective

effect and may be useful in future studies on the pathogenesis and

prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD)

(12–15). However, the precise biochemical

mechanisms underlying the G. lucidum extract-induced

anti-inflammatory effects have not yet been clarified in microglial

cells.

Microglia are the resident macrophage-like cells in

the brain that play a major role in host defense and tissue repair

in the central nervous system (CNS) (16,17).

However, under pathological conditions, activated microglia release

neurotoxic and pro-inflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide

(NO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), reactive

oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including

interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α

(18,19). Overproduction of these inflammatory

mediators and cytokines causes severe neurodegenerative diseases,

including AD, PD, cerebral ischemia, multiple sclerosis and trauma

(20–22). Activated microglia are a major

cellular source of pro-inflammatory and/or cytotoxic factors that

cause neuronal damage in the CNS. Previous studies have also

demonstrated that a decrease in the number of pro-inflammatory

mediators in microglia may attenuate the severity of these

disorders (23–25).

In the present study, we investigated the inhibitory

effects of an ethanol extract of G. lucidum (EGL) and the

mechanism of its anti-inflammatory action against the

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated pro-inflammatory responses in

murine BV2 microglia. Our results indicate that EGL inhibits

inflammatory reactions by inhibiting nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and

toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways, suggesting that EGL

may be useful for the treatment of neuroinflammatory and

neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and methods

Preparation of EGL

EGL was supplied by Dongeui University Oriental

Hospital (Busan, Korea). The freeze-dried and milled G.

lucidum fruiting bodies (200 g) were extracted with 25% ethanol

(4 liters) at room temperature for 10 h using a blender. The

extracts were filtered through a Whatman no. 2 filter (Maidstone,

UK), concentrated to 500 ml under vacuum conditions and then stored

at −20°C (11). The EGL solution

was directly diluted in medium prior to assay.

Cell culture

The murine BV2 cell line was maintained in

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin

(Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37°C in a humidified

incubator with 5% CO2. The cells were pre-treated with

the indicated EGL concentrations for 1 h before adding LPS (0.5

μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell viability

was evaluated by the

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT;

Sigma-Aldrich) reduction assay. In brief, cells (1×105

cells/ml) were seeded and treated with EGL and/or LPS for the

indicated time periods. Following treatment, the medium was removed

and the cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution. After a 3

h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the supernatant was

removed and formation of formazan was measured at 540 nm with a

microplate reader (Dynatech MR-7000; Dynatech Laboratories Inc., El

Paso, TX, USA).

NO production

NO concentrations in culture supernatants were

determined by measuring nitrite, which is a major stable product of

NO, using Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells (5×105

cells/ml) were stimulated in 24-well plates for 24 h, then 100

μl culture medium was mixed with an equal volume of Griess

reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine

dihydrochloride and 2.5% H3PO4). Nitrite

levels were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) plate reader at 540 nm and nitrite concentrations were

calculated by reference to a standard curve generated using known

concentrations of sodium nitrite (26).

Measurement of PGE2

production

BV2 cells were sub-cultured in 6-well plates

(5×105 cells/ml) and incubated with the indicated

concentrations of EGL in the presence or absence of LPS (0.5

μ/ml) for 24 h. A 100 μl aliquot of the

culture-medium supernatant was collected for determination of the

PGE2 concentration by ELISA (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor,

MI, USA).

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the cells using the

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

The total RNA (1.0 μg) was reverse-transcribed using M-MLV

reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) to

produce cDNAs. The inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS),

cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, IL-1β and TNF-α genes were amplified from

the cDNA using PCR. The PCR primers were as follows: mouse iNOS,

5′-ATG TCC GAA GCA AAC ATC AC-3′ and 5′-TAA TGT CCA GGA AGT AGG

TG-3′; COX-2, 5′-CAG CAA ATC CTT GCT GTT CC-3′ and 5′-TGG GCA AAG

AAT GCA AAC ATC-3′; IL-1β, 5′-ATG GCA ACT GTT CCT GAA CTC AAC T-3′

and 5′-TTT CCT TTC TTA GAT ATG GAC AGG AC-3′; and TNF-α, 5′-ATG AGC

ACA GAA AGC ATG ATC-3′ and 5′-TAC AGG CTT GTC ACT CGA ATT-3′.

Following amplification, the PCR products were electrophoresed on

1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich)

staining. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an

internal control.

Protein extraction and western blot

analysis

Cells were washed three times with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in lysis buffer (1%

Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate and 0.1% NaN3) containing protease

inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). In a parallel

experiment, nuclear and cytosol proteins were prepared using

NE-PER® nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents

(Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. For the western blot analysis, equal

amounts of protein were subjected to electrophoresis on sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to

nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell Inc., Keene, NH,

USA) by electroblotting. Blots were probed with the desired

antibodies for 1 h, incubated with the diluted enzyme-linked

secondary antibodies and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence

(Amersham Co., Arlington Heights, IL, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Actin and nucleolin were used as

internal controls for the cytosolic and nuclear fractions,

respectively. Antibodies against iNOS, COX-2, IκB-α, NF-κB p65,

TLR4 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) were purchased

from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies

against actin and nucleolin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin and fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG were

purchased from Amersham Co. and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively.

Cytokine assays

The levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were measured using

ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, BV2 cells (5×105

cells/ml) were plated in 24-well plates and pre-treated with the

indicated EGL concentrations for 1 h prior to treatment with 0.5

μg/ml LPS for 24 h. A 100 μl aliquot of each

culture-medium supernatant was collected for determination of the

IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations by ELISA.

NF-κB luciferase assay

A total of 1×106 BV2 cells were

transfected with 2 μg NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmids (BD

Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using Lipofectamine according to

the manufacturer’s instructions (Gibco-BRL). Then, the cells were

pre-incubated in the presence or absence of EGL before being

stimulated with LPS for 6 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS and

lysed with reporter lysis buffer (Promega Corporation). Following

vortexing and centrifuging at 12,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C, the

supernatant was stored at −70°C. For the luciferase assay, 20

μl cell extract was mixed with 100 μl luciferase

assay reagent at room temperature, then, the mixture was analyzed

using a LB96V microplate luminometer (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA,

USA) (27).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Statistical significance was determined using an analysis of

variance followed by the Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of EGL on NO and PGE2

production in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia

The potential anti-inflammatory properties of EGL

were evaluated against the production of two major inflammatory

mediators, NO and PGE2, in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia.

To determine the levels of NO and PGE2 production, the

amounts of nitrite and PGE2 released into the culture

medium were measured using Griess reagent and ELISA, respectively.

According to the NO detection assay result, LPS alone markedly

induced NO production from cells compared with the control

(Fig. 1A). However, pre-treatment

with EGL significantly repressed the levels of NO production in the

LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia in a concentration-dependent manner,

up to 1 μg/ml. Under the same conditions, stimulating the

cells with LPS also resulted in a significant increase in

PGE2 production; however, this was markedly repressed by

pre-treatment with EGL (Fig.

1B).

Effects of EGL on cell viability in

LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia

The cells were exposed to EGL for 24 h in the

presence or absence of LPS to exclude a cytotoxic effect of EGL on

BV2 cell growth. Cell viability was then measured by the MTT assay.

As indicated in Fig. 2, the

concentrations of EGL (0.1–1 mg/ml) used to inhibit NO and

PGE2 production did not affect cell viability. The

results clearly indicate that the inhibition of NO and

PGE2 production in the LPS-stimulated BV2 cells was not

due to a cytotoxic effect of EGL.

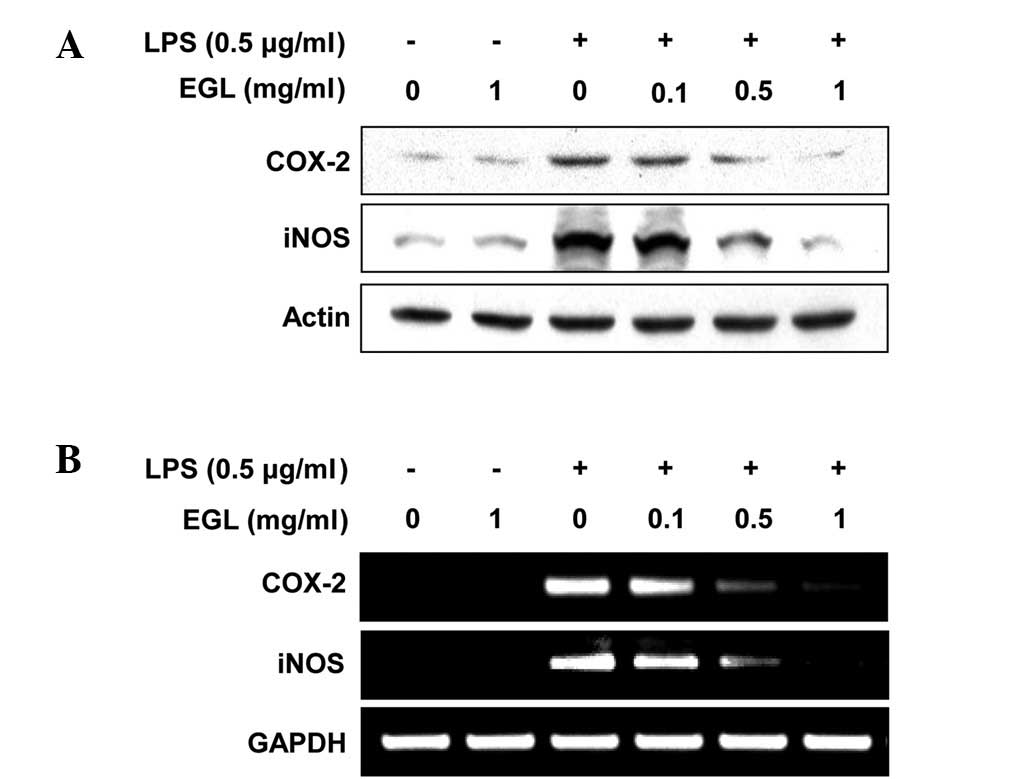

Effects of EGL on LPS-stimulated iNOS and

COX-2 expression

RT-PCR and western blot analyses were carried out to

determine whether the inhibition of NO and PGE2

production by EGL in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells was associated with

reduced levels of iNOS and COX-2 expression. As shown in Fig. 3, iNOS and COX-2 protein levels were

markedly upregulated following 24 h of treatment with LPS (0.5

μg/ml) alone; however, EGL significantly inhibited the iNOS

and COX-2 protein expression in the LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia in

a concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

3A). The effects of EGL on iNOS and COX-2 mRNA expression were

evaluated to investigate whether EGL suppressed the LPS-mediated

induction of iNOS and COX-2 at the pre-translational level. RT-PCR

data revealed that the reduction in iNOS and COX-2 mRNAs correlated

with the reduction in the corresponding protein levels (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that

EGL-induced reductions in iNOS and COX-2 expression were the cause

of the reduced NO and PGE2 production levels.

Effects of EGL on LPS-induced IL-1β and

TNF-α production and mRNA expression

The effects of EGL on the production of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α, were

analyzed using ELISA. BV2 cells were incubated with various

concentrations of EGL in the presence or absence of LPS (0.5

μg/ml) for 24 h and cytokine levels in the culture media

were measured. As shown in Fig. 4,

the IL-1β and TNF-α levels were markedly increased in the culture

media of the LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia. However, pre-treatment

with EGL significantly reduced the release of these

pro-inflammatory cytokines in a concentration-dependent manner. In

a parallel experiment, the effects of EGL on LPS-induced IL-1β and

TNF-α mRNA expression were studied using RT-PCR. As shown in

Fig. 5, IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA

transcription levels also decreased following EGL treatment. These

results suggest that EGL was effective in suppressing

pro-inflammatory cytokine production by altering IL-1β and TNF-α

transcription levels in activated microglia.

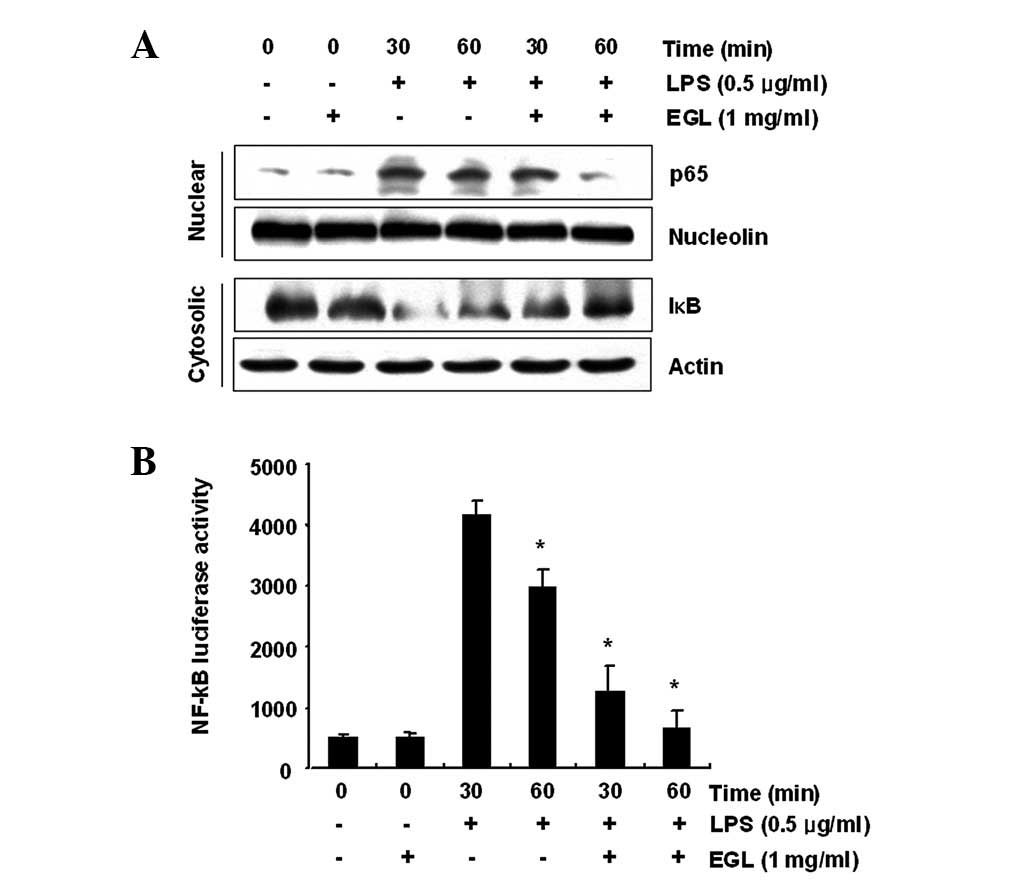

Effects of EGL on LPS-induced NF-κB

activity

Activation of NF-κB is crucial for the induction of

iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α and IL-1β genes in activated BV2 microglia

(28,29). To further characterize the

mechanism through which EGL inhibits pro-inflammatory and/or

cytotoxic factor expression, the ability of EGL to prevent

translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit to the nucleus was first

examined. Western blot analysis revealed that the amount of NF-κB

p65 in the nucleus markedly increased following exposure to LPS

alone; however, the LPS-induced p65 level in the nuclear fraction

was reduced following EGL pre-treatment (Fig. 6A). In addition, the ability of EGL

to block the LPS-stimulated degradation of IκB-α was investigated

by western blotting. As shown in Fig.

6A, IκB-α was markedly degraded at 30 min after LPS treatment;

however, this LPS-induced IκB-α degradation was significantly

reversed by EGL. Furthermore, the inhibition of LPS-induced NF-κB

activation by EGL was confirmed using a luciferase assay. BV2 cells

transfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmids were

pre-treated with EGL for 1 h then, following stimulation with LPS

for 6 h, luciferase activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 6B, LPS significantly enhanced the

NF-κB activity up to ∼8-fold over the basal level, whereas EGL

significantly inhibited the LPS-induced NF-κB activity. These

findings show that the anti-inflammatory effect of EGL in

LPS-stimulated BV2 cells involves the NF-κB pathway.

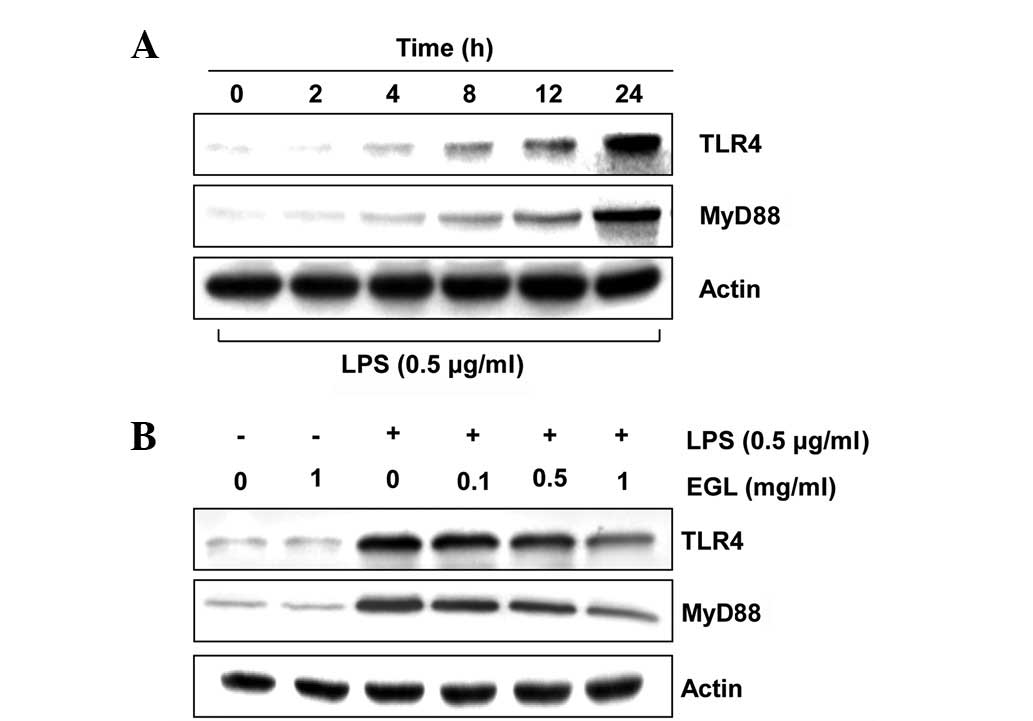

Effects of EGL on the levels of

LPS-induced TLR4 and MyD88

Previous studies established that the inflammatory

response to LPS completely relies on the presence of TLR4, which

triggers the intracellular association of MyD88 with its cytosolic

domain (30–32). To investigate whether the

anti-inflammatory activity of EGL is associated with the modulation

of these proteins, the effects of EGL on LPS-induced upregulation

of TLR4 and MyD88 in BV2 cells were examined. As shown in Fig. 7, EGL concentration-dependently

attenuated the LPS-stimulated increase in TLR4 and MyD88

expression. This finding indicates that EGL is capable of

disrupting key signal transduction pathways, including TLR

signaling pathways activated by LPS in BV2 microglia, which

subsequently prevents the production of pro-inflammatory mediators

and cytokines.

Discussion

G. lucidum is an edible basidiomycete

white-rot macrofungus mushroom that has long been prescribed to

prevent and treat various human diseases, particularly in Asian

countries (1–4). Extensive study has been carried out

on the therapeutic potential of G. lucidum. The exact

ingredients in G. lucidum have not yet been identified;

however, the major active ingredients include polysaccharides,

triterpenoids, unsaturated fatty acids and ergosterol (2,33–35).

Although previous reports have indicated that G. lucidum

extracts exhibit inhibitory actions on neurotoxicity (12–15),

the anti-inflammatory and related immune responses remain poorly

understood. Therefore, we investigated the inhibitory effects of

EGL on the production of LPS-stimulated pro-inflammatory mediators

and cytokines in BV2 microglia to evaluate the cellular and

molecular mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory effects of this

traditional medicine.

COXs are enzymes that catalyze the conversion of

arachidonic acid to PGH2, which is the precursor of a

variety of biologically active mediators, including

PGE2, prostacyclin and thromboxane A2. COXs

exist as two major isozymes: COX-1, a constitutive COX, and COX-2,

an isoform that is induced during the responses to a number of

stimulants and is activated at the inflammation site (36,37).

Several studies have reported that COX-2 is associated with

cytotoxicity in brain diseases, since the inhibition of COX-2

induction and/or activity reduces brain injury following ischemia

and slows the progression of AD and PD (38). Additionally, NO is an important

regulatory molecule in diverse physiological functions, including

vasodilation, neural communication and host defense (39,40).

In mammalian cells, NO is synthesized from three different isoforms

of NOS, including endothelial NOS, neuronal NOS and iNOS. Activated

microglial cells are a major cellular source of iNOS in the brain

and the excessive release of NO by activated microglia is

correlated with the progression of neurodegenerative disorders. The

major producers of TNF-α in the brain are microglia and they may

play a role in a number of pathological conditions of the brain

(17,41,42).

Therefore, TNF-α overexpression has been implicated in the

pathogenesis of several human CNS disorders (18,43,44).

IL-1β is also a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that acts through

IL-1 receptors on numerous cell types, including neurons and

microglia. Moreover, IL-1β is an important mediator of neuroimmune

interactions that participate directly in neurodegeneration

(45). Thus, inhibiting

inflammatory mediator and cytokine production or function serves as

a key mechanism for identifying a treatment for inflammatory

diseases, including brain injury. In the present study, EGL

significantly suppressed LPS-stimulated PGE2 and NO

production in BV2 microglia in a concentration-dependent manner

without affecting cell viability (Figs. 1 and 2), which appeared to be due to the

transcriptional suppression of COX-2 and iNOS (Fig. 3). Our data also indicate that

treatment with EGL prior to LPS significantly attenuates the

production of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, by

inhibiting their expression at the transcriptional level (Figs. 4 and 5). These results suggest that the

anti-inflammatory activity of EGL may contribute to the suppressive

effects of COX-2, iNOS, TNF-α and IL-1β in LPS-activated BV2

microglia.

NF-κB, as a result of its key role in several

pathological conditions, is a major drug target for a variety of

diseases. NF-κB is also a primary regulator of genes that are

involved in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and

enzymes involved in the process of inflammation (28,29).

NF-κB is normally located in the cytoplasm where it is complexed

with an inhibitory IκB protein. In response to pro-inflammatory

stimuli, IκB is phosphorylated and subsequently degraded. NF-κB is

then released and translocated to the nucleus where it promotes the

expression of inflammation-related genes. Moreover, blocking the

transcriptional activity of NF-κB in microglial nuclei also

suppresses the expression of iNOS, COX-2 and pro-inflammatory

cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α (46,47).

Our results indicate that EGL inhibits LPS-induced IκB-α

degradation, nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit and

NF-κB transcriptional activity in BV2 microglia (Fig. 6). Therefore, inhibition of the

NF-κB signaling pathway in microglia by EGL may result in the

downregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, resulting in an

anti-inflammatory effect.

TLR family members are receptors of the innate

immune system that recognize pathogen-associated molecular

patterns. Among them, TLR4 acts as a major LPS signaling receptor,

leading to the activation of key transcription factors, including

NF-κB and activator protein (AP)-1, which, in turn, enhance the

synthesis of effector inflammatory genes, including cytokines and

chemokines (30–32,48).

Stimulation of the TLR4 extracellular domain by LPS or endotoxins

sequentially triggers the intracellular association of MyD88 with

its cytosolic domain (30,49). Therefore, MyD88 serves as a key

TLR4 adaptor protein, linking the receptors to downstream kinases,

suggesting that TLR4 and MyD88 act as specific targets for

inflammatory responses (30,48,50).

Our data clearly demonstrate that EGL markedly inhibits LPS-induced

TLR4 and MyD88 expression in BV2 microglia (Fig. 7). These results suggest that TLR4

and MyD88 are involved in the inhibitory effects of EGL on the

LPS-induced expression of NO, PGE2 and pro-inflammatory

cytokines.

In summary, we identified that EGL significantly

attenuates the LPS-induced release of inflammatory mediators and

cytokines, including NO, PGE2, TNF-α and IL-1β.

Moreover, it acts at the transcriptional level in BV2 microglia.

The anti-inflammatory action of EGL is mediated by the prevention

of the activation of NF-κB and inhibition of IκB-degradation and

possibly by inhibition of the TLR signaling pathway. Thus, EGL may

provide an effective treatment for a number of neurodegenerative

diseases; however, the pharmacology and mode of action of its

active components require further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a research

grant from Dong-A University, Republic of Korea.

References

|

1.

|

Mahajna J, Dotan N, Zaidman BZ, Petrova RD

and Wasser SP: Pharmacological values of medicinal mushrooms for

prostate cancer therapy: the case of Ganoderma lucidum. Nutr

Cancer. 61:16–26. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Boh B, Berovic M, Zhang J and Zhi-Bin L:

Ganoderma lucidum and its pharmaceutically active compounds.

Biotechnol Annu Rev. 13:265–301. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3.

|

Paterson RR: Ganoderma - a

therapeutic fungal biofactory. Phytochemistry. 67:1985–2001. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4.

|

Yuen JW and Gohel MD: Anticancer effects

of Ganoderma lucidum: a review of scientific evidence. Nutr

Cancer. 53:11–17. 2005.

|

|

5.

|

Chien CM, Cheng JL, Chang WT, Tien MH,

Tsao CM, Chang YH, Chang HY, Hsieh JF, Wong CH and Chen ST:

Polysaccharides of Ganoderma lucidum alter cell

immunophenotypic expression and enhance CD56+ NK-cell

cytotoxicity in cord blood. Bioorg Med Chem. 12:5603–5609.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Hu H, Ahn NS, Yang X, Lee YS and Kang KS:

Ganoderma lucidum extract induces cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell. Int J Cancer.

102:250–253. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7.

|

Lin SB, Li CH, Lee SS and Kan LS:

Triterpene-enriched extracts from Ganoderma lucidum inhibit

growth of hepatoma cells via suppressing protein kinase C,

activating mitogen-activated protein kinases and G2-phase cell

cycle arrest. Life Sci. 72:2381–2390. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Hong KJ, Dunn DM, Shen CL and Pence BC:

Effects of Ganoderma lucidum on apoptotic and

anti-inflammatory function in HT-29 human colonic carcinoma cells.

Phytother Res. 18:768–770. 2004.

|

|

9.

|

Stanley G, Harvey K, Slivova V, Jiang J

and Sliva D: Ganoderma lucidum suppresses angiogenesis

through the inhibition of secretion of VEGF and TGF-β1 from

prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 330:46–52. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10.

|

Müller CI, Kumagai T, O’Kelly J, Seeram

NP, Heber D and Koeffler HP: Ganoderma lucidum causes

apoptosis in leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma cells. Leuk

Res. 30:841–848. 2006.

|

|

11.

|

Jang KJ, Han MH, Lee BH, Kim BW, Kim CH,

Yoon HM and Choi YH: Induction of apoptosis by ethanol extracts of

Ganoderma lucidum in human gastric carcinoma cells. J

Acupunct Meridian Stud. 3:24–31. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Cheung WM, Hui WS, Chu PW, Chiu SW and Ip

NY: Ganoderma extract activates MAP kinases and induces the

neuronal differentiation of rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. FEBS

Lett. 486:291–296. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13.

|

Zhao HB, Lin SQ, Liu JH and Lin ZB:

Polysaccharide extract isolated from Ganoderma lucidum

protects rat cerebral cortical neurons from hypoxia/reoxygenation

injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 95:294–298. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Lai CS, Yu MS, Yuen WH, So KF, Zee SY and

Chang RC: Antagonizing beta-amyloid peptide neurotoxicity of the

anti-aging fungus Ganoderma lucidum. Brain Res.

1190:215–224. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Zhou ZY, Tang YP, Xiang J, Wua P, Jin HM,

Wang Z, Mori M and Cai DF: Neuroprotective effects of water-soluble

Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides on cerebral ischemic

injury in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 131:154–164. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Perry VH and Gordon S: Macrophages and

microglia in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 92:273–274.

1998.

|

|

17.

|

Sawada M, Kondo N, Suzumura A and

Marunouchi T: Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by

microglia and astrocytes in culture. Brain Res. 491:394–397. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Meda L, Cassatella MA, Szendrei GI, Otvos

L Jr, Baron P, Villalba M, Ferrari D and Rossi F: Activation of

microglial cells by β-amyloid protein and interferon-γ. Nature.

373:647–650. 1995.

|

|

19.

|

Dandona P, Ghanim H, Chaudhuri A, Dhindsa

S and Kim SS: Macronutrient intake induces oxidative and

inflammatory stress: potential relevance to atherosclerosis and

insulin resistance. Exp Mol Med. 42:245–253. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Gonzalez-Scarano F and Baltuch G:

Microglia as mediators of inflammatory and degenerative diseases.

Annu Rev Neurosci. 22:219–240. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Amor S, Puentes F, Baker D and van der

Valk P: Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology.

129:154–169. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22.

|

Dheen ST, Kaur C and Ling EA: Microglial

activation and its implications in the brain diseases. Curr Med

Chem. 14:1189–1197. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Eikelenboom P and van Gool WA:

Neuroinflammatory perspectives on the two faces of Alzheimer’s

disease. J Neural Transm. 111:281–294. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Gao HM, Liu B, Zhang W and Hong JS: Novel

anti-inflammatory therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Trends Pharmacol

Sci. 24:395–401. 2003.

|

|

25.

|

Liu B and Hong JS: Role of microglia in

inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and

strategies for therapeutic intervention. J Pharmacol Exp Ther.

304:1–7. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Bae DS, Kim YH, Pan CH, Nho CW, Samdan J,

Yansan J and Lee JK: Protopine reduces the inflammatory activity of

lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine macrophages. BMB Rep.

45:108–113. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Jin CY, Moon DO, Lee KJ, Kim MO, Lee JD,

Choi YH, Park YM and Kim GY: Piceatannol attenuates

lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation and

NF-kappaB-related proinflammatory mediators in BV2 microglia.

Pharmacol Res. 54:461–467. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28.

|

Lee JW, Lee MS, Kim TH, Lee HJ, Hong SS,

Noh YH, Hwang BY, Ro JS and Hong JT: Inhibitory effect of

inflexinol on nitric oxide generation and iNOS expression via

inhibition of NF-κB activation. Mediators Inflamm.

2007:93148–93157. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Baima ET, Guzova JA, Mathialagan S, Nagiec

EE, Hardy MM, Song LR, Bonar SL, Weinberg RA, Selness SR, Woodard

SS, Chrencik J, Hood WF, Schindler JF, Kishore N and Mbalaviele G:

Novel insights into the cellular mechanisms of the

anti-inflammatory effects of NF-κB essential modulator binding

domain peptides. J Biol Chem. 285:13498–13506. 2010.

|

|

30.

|

Miller SI, Ernst RK and Bader MW: LPS,

TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 3:36–46.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Lee YH, Jeon SH, Kim SH, Kim C, Lee SJ,

Koh D, Lim Y, Ha K and Shin SY: A new synthetic chalcone

derivative, 2-hydroxy-3′,5,5′-trimethoxychalcone (DK-139),

suppresses the Toll-like receptor 4-mediated inflammatory response

through inhibition of the Akt/NF-κB pathway in BV2 microglial

cells. Exp Mol Med. 44:369–377. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Romanovsky AA, Steiner AA and Matsumura K:

Cells that trigger fever. Cell Cycle. 5:2195–2197. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Fukuzawa M, Yamaguchi R, Hide I, Chen Z,

Hirai Y, Sugimoto A, Yasuhara T and Nakata Y: Possible involvement

of long chain fatty acids in the spores of Ganoderma lucidum

(Reishi Houshi) to its anti-tumor activity. Biol Pharm Bull.

31:1933–1937. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Sanodiya BS, Thakur GS, Baghel RK, Prasad

GB and Bisen PS: Ganoderma lucidum: a potent pharmacological

macrofungus. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 10:717–742. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35.

|

Xu Z, Chen X, Zhong Z, Chen L and Wang Y:

Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides: immunomodulation and

potential anti-tumor activities. Am J Chin Med. 39:15–27. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36.

|

Vane JR, Mitchell JA, Appleton I,

Tomlinson A, Bishop-Bailey D, Croxtall J and Willoughby DA:

Inducible isoforms of cyclooxygenase and nitric-oxide synthase in

inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91:2046–2050. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37.

|

Hawkey CJ: Cox-2 inhibitors. Lancet.

353:307–314. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38.

|

Giovannini MG, Scali C, Prosperi C,

Bellucci A, Pepeu G and Casamenti G: Experimental brain

inflammation and neurode-generation as model of Alzheimer’s

disease: protective effects of selective COX-2 inhibitors. Int J

Immunopathol Pharmacol. 16:31–40. 2003.

|

|

39.

|

MacMicking J, Xie QW and Nathan C: Nitric

oxide and macrophage function. Ann Rev Immunol. 15:323–330. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Mitchell JA, Larkin S and Williams TJ:

Cyclooxygenase-2: regulation and relevance in inflammation. Biochem

Pharmacol. 50:1535–1542. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

Boka G, Anglade P, Wallach D, Javoy-Agid

F, Agid Y and Hirsch EC: Immunocytochemical analysis of tumor

necrosis factor and its receptors in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci

Lett. 172:151–154. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Murphy S: Production of nitric oxide by

glial cells: regulation and potential roles in the CNS. Glia.

29:1–13. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43.

|

Akassoglou K, Bauer J, Kassiotis G,

Pasparakis M, Lassmann H, Kollias G and Probert L: Oligodendrocyte

apoptosis and primary demyelination induced by local TNF/p55TNF

receptor signaling in the central nervous system of transgenic

mice: models for multiple sclerosis with primary

oligodendrogliopathy. Am J Pathol. 153:801–813. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44.

|

Sriram K, Matheson JM, Benkovic SA, Miller

DB, Luster MI and O’Callaghan JP: Mice deficient in TNF receptors

are protected against dopaminergic neurotoxicity: implications for

Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 16:1474–1476. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45.

|

Rothwell N, Allan S and Toulmond S: The

role of interleukin 1 in acute neurodegeneration and stroke:

pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. J Clin Invest.

100:2648–2652. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46.

|

Baldwin AS Jr: The NF-kappaB and I-kappaB

proteins: new discoveries and insights. Ann Rev Immunol.

14:649–683. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47.

|

Moon DO, Choi YH, Kim ND, Park YM and Kim

GY: Anti-inflammatory effects of β-lapachone in

lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV2 microglia. Int Immunopharmacol.

7:506–514. 2007.

|

|

48.

|

Trinchieri G and Sher A: Cooperation of

Toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defence. Nat Rev

Immunol. 7:179–190. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49.

|

Medzhitov R: Toll-like receptors and

innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 1:135–145. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50.

|

Seki E, Tsutsui H, Iimuro Y, Naka T, Son

G, Akira S, Kishimoto T, Nakanishi K and Fujimoto J: Contribution

of Toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling

to murine liver regeneration. Hepatology. 41:443–450. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|