Introduction

Laryngeal carcinoma is a common head and neck

malignancy with high incidence, accounting for approximately 2.4%

of new malignancies worldwide each year (1,2).

Despite extensive application of different treatment modalities,

invasion and metastasis remain the main causes of mortality for

laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) patients. Current

treatments, including surgical intervention, radiation therapy and

chemotherapy, are moderately effective in the early-stage cases,

but are less effective in more advanced cases (3). The mechanisms behind the occurrence

and development of LSCC remain unclear. Therefore, a novel

therapeutic strategy for the treatment of LSCC is urgently

required.

Research over the past years clearly implicates

multiple genetic alterations in the development and progression of

laryngeal carcinoma (4). In

laryngeal carcinoma, alterations in the expression profiles of

several genes have been reported, including those that have

important functions in cell adhesion, signal transduction, cell

differentiation, metastasis, DNA repair and glycosylation (5).

B-cell-specific MLV integration site-1 (Bmi-1) has

been detected in a variety of human carcinoma specimens, from the

pre-cancerous to the advanced stages. In particular, Bmi-1 is

overexpressed in a number of malignancies, including mantle cell

lymphoma (6), B-cell

non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (7),

myeloid leukemia (8), non-small

cell lung cancer (9), colorectal

cancer (10), as well as breast

and prostate cancers (11,12).

Recently, our group reported that Bmi-1 is also overexpressed in

head and neck cancers (13),

particularly in nasopharyngeal and oral cancers (14,15). Gene chip analysis also showed that

Bmi-l can be used to predict the rapid recurrence of a variety of

cancers following treatment, as well as to predict metastasis

(16), by cooperating with H-RAS

in promoting breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion,

resisting apoptosis, and enhancing transfer capabilities, including

brain metastasis (17). Bmi-1 is

a key protein responsible for cell cycle arrest in response to DNA

damage and plays a role in genetic stability and cancer

susceptibility. It mediates cell cycle arrest at the G1/S, S and

G2/M phase to prevent the processing of damaged DNA (18).

RNA interference (RNAi) is a new technique for the

effective suppression of gene expression (19). RNAi mediated by small interfering

RNA (siRNA) has become an excellent tool for exploring gene

function in basic research and may become a promising strategy for

cancer gene therapy due to its high efficiency and specificity in

blocking target gene expression (20–22). However, to our knowledge, siRNA

targeting Bmi-1 for the treatment of laryngeal carcinoma has not

been reported thus far. In this study, we designed and constructed

siRNA against Bmi-1 and investigated its efficacy in suppressing

Bmi-1 expression in the laryngeal carcinoma cell line, HEp-2, which

expresses high levels of Bmi-1, to develop an antitumor reagent. We

show that the specific downregulation of Bmi-1 by siRNA is

sufficient to inhibit the growth of HEp-2 cells in vitro and

in vivo. Furthermore, we explored the mechanisms through

which Bmi-1 induces oncogenesis and tumor progression.

Materials and methods

Construction of lentiviral vector

We selected four different target sequences specific

to Bmi-1 (Table I) with the

online siRNA tool provided by Invitrogen (http://www.invitrogen.com/rnai), using the Bmi-1

reference sequence (GenBank accession no. NM 005180.5).

Double-stranded DNA containing the interference sequences was

synthesized according to the structure of a pGCSIL-GFP viral vector

(Gikai Gene Company, Shanghai, China) (Fig. 1), and then inserted into a

linearized vector. All the constructs were cloned and sequenced to

confirm their structure. The positive clones were identified as

lentiviral vectors that expressed human Bmi-1 short hairpin RNA

(shRNA), hereinafter designated as pGCSIL/Bmi-1-A, pGCSIL/Bmi-1-B,

pGCSIL/Bmi-1-C and pGCSIL/Bmi-1-D. The four lentiviral vectors were

transfected into HEp-2 cells separately to evaluate their RNAi

effects. We then co-transfected the pGCSIL/Bmi-1-D vector and the

viral packaging system (containing an optimized mixture of two

packaging plasmids, pHelper 1.0 and pHelper 2.0 vector; Gikai Gene

Company) into HEp-2 cells to replicate competent lentivirus. Viral

supernatant was harvested at 48 h after transfection, filtered

through a 0.45-mm cellulose acetate filter, and then frozen at

−70°C. The lentivirus containing the human Bmi-1 shRNA expressing

cassette (pGCSIL/Bmi-1-D) was used as the positive control for

lentivirus production, denoted as Bmi-1-RNAi-LV. The pGCSIL/U6 mock

vector was also packaged and used as the negative control, denoted

as NC-GFP-LV. Viral concentrations were determined by serial

dilution of the concentrated vector stocks in HEp-2 cells in

96-well plates. The number of green fluorescent protein

(GFP)-positive cells was measured at four days post-transduction

under a microscope. The titers averaged 1×108 TU/ml.

| Table ICore target recognition sequences of

siRNAs from human Bmi-1 cDNA. |

Table I

Core target recognition sequences of

siRNAs from human Bmi-1 cDNA.

| Marker | Species | Target

sequence |

|---|

| Bmi-1-A | Human |

GGAGGAACCTTTAAAGGAT |

| Bmi-1-B | Human |

CCAGAGAGATGGACTGACA |

| Bmi-1-C | Human |

ACAGGAAACAGTATTGTAT |

| Bmi-1-D | Human |

GGAGGAGGTGAATGATAAA |

Cell culture and lentiviral transduction

of HEp-2

For lentiviral transduction, the HEp-2 cells were

plated into six-well plates at a density of 1×106

cells/well. When the cells reached 30% confluence (typically on day

three after subculturing), the medium was replaced with 1 ml of

fresh medium containing lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection

(MOI) of 5 and 6 μg/ml polybrene (Gikai Gene Company). The medium

was replaced with fresh medium on the following day.

Real-time reverse-transcription PCR

(real-time RT-PCR)

The expression of Bmi-1 mRNA in first passage

untransfected or transfected HEp-2 cells was detected, with actin

as the normalizing control. The specific PCR primer sequences of

these genes designed by Beacon Designer 2 software were as follows:

Bmi-1 forward, 5′-TGGCTCGCATTCATTTTCTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGTAGTGGTCTGGTCTT GTG-3′; actin forward, 5′-GTG

GACATCCGCAAAGAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAAGGGTGT AACGCAACTA-3′.

Transduced HEp-2 cells were trypsinized and harvested at five days

after transduction. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen-Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and cDNA was acquired

according to the M-MLV reverse transcription procedures (Promega,

Madison, WI) with 2 μg of total RNA. Two-step real-time RT-PCR

reactions were carried out using the TP800 Real-Time PCR System

(Takara), which included cycle 1 (1X) at 95°C for 15 sec and cycle

2 (45X) at 95°C for 5 sec, and 60°C for 30 sec. Absorbance data

were collected at the end of every extension (60°C) and graphed

using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software. The real-time PCR data were

analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Table II).

| Table IIQuantitative results of Bmi-1 mRNA

expression by real-time PCR. |

Table II

Quantitative results of Bmi-1 mRNA

expression by real-time PCR.

| Vector | ΔΔCt |

2−ΔΔCt |

|---|

| Control | 0.053±0.05 | 0.972±0.124 |

| NC-GFP-Bmi-1 | −0.003±0.15 | 0.999±0.106 |

| Bmi-1-RNAi-LV | −2.663±0.32 | 0.16±0.036 |

Western blot analysis

For western blot analysis, cells were washed three

times with PBS, homogenized in cell lysis buffer (50 mmol/l Tris,

pH 7.8, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1% nonidet P-40) containing 10 μl/ml

protease inhibitor (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), incubated on ice for 30

min, and then centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 rpm. The aqueous

supernatant was collected and quantified using Bradford Reagent

(Sigma). Individual samples, each containing 30 μg of protein, were

separated on a precast 12.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel in a Tris-HCl

buffer (pH 7.4) and blotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane

(Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membrane was incubated at room

temperature for 1 h in PBST buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, 0.05% Triton

X-100) containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin to block

non-specific protein binding sites. After blocking, the blots were

probed with a goat anti-Bmi-1 antibody (ab25791, 1:200; Abcam)

overnight at 4°C, followed by five washes with PBST. The blots were

then incubated with an anti-goat IgG (1:5,000, sc-2020; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 h at room temperature.

After washing, the immunoreactive bands were detected using a

chemiluminescent substrate (NEN Life Science, Inc.). Subsequently,

the blots were reprobed with a mouse anti-GAPDH control antibody

(1:6,000, sc32233; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

MTT assay

Transfected and control HEp-2 cells

(5×105/well) were plated into a 96-well plate in

octuple. For six consecutive days, 20 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) were

added daily to each well, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for

an additional 4 h. The reaction was stopped by lysing the cells

with 200 μl of DMSO for 5 min. Quantification was carried out at

570 nm and expressed as a percentage of the control.

Cell cycle analysis by flow

cytometry

Parental HEp-2 cells and control siRNA-transfected

cells were harvested with 0.125% trypsin, washed twice in PBS,

counted, and fixed overnight with 70% (v/v) ethanol. Cells were

then centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min, resuspended at a

concentration of 1×106 well/ml in PBS, followed by RNase

incubation at 37°C for 30 min. The nuclei of cells were then

stained with propidium iodide (PI) for another 30 min. A total of

10,000 nuclei were examined in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA); DNA histograms were analyzed

by ModFit software.

Apoptosis detected by flow cytometry

Each of the cell lines were seeded in 24-well

culture plates and divided into the following groups: Bmi-1-RNAi-LV

group, negative control group and control group. Each group

contained five culture flasks. When the cells reached 70–80%

confluence after 48 h, the cells were harvested and washed in cold

PBS. Annexin V and PI staining were carried out using the Annexin

V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. After 20 min of incubation in the dark

at room temperature, the cells were immediately analyzed by an

Epics Elite ESP flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Inc.).

Migration assay

The migration of the cells was assessed by a

modified Boyden chamber method using microchemotaxis chambers

(Transwell; Corning-Costar, Acton, MA) with a polycarbonate

membrane filter (8.0 μm pore size, 0.33 cm2 growth

area). In all the experiments, both sides of the membrane were

pre-coated with laminin (5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h, and then

air-dried. Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added

to the lower chambers as a chemoattractant. The subconfluent HEp-2

cells at passage 1, with or without Bmi-1-RNAi-LV treatment, were

trypsinized and resuspended in 2% FBS to a concentration of

7×105 cells/ml. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the

upper surface of the membrane filters was scraped with a cotton

swab to remove non-migrated cells, and then fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Migrating cells

that passed through the Transwell filter pores and attached on the

lower surface of the filters were counted in five non-overlapping

fields following nuclear staining with hematoxylin. The experiments

were carried out in triplicate.

Wound healing assay

Cells were cultured and grown to 100% confluence. A

clear area was then scraped in the monolayer with a 200-μl pipette

tip. After washing with serum-free RPMI-1640 medium, the cells were

incubated in RPMI-1640 medium containing 5% FBS at 37°C. The

migration of cells into the wounded areas was evaluated at the

indicated times using an inverted microscope, and then

photographed. The healing rate was quantified with measurements of

the gap size during culturing. Three different areas in each assay

were selected to measure the distance of the migrating cells to the

origin of the wound.

Colony formation analysis

Minimal concentrations of FBS (2%) were added to the

medium to measure the cell colony formation ability. Briefly, HEp-2

cells, transfected with anti-Bmi-1 siRNA and negative control RNA,

were plated in six-well plates in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10%

FBS at a density of 1,000 cells/well. After 4 h, the medium was

changed to FBS (2%)-supplemented medium. After ten days of

incubation at 37°C in an incubator under a humidified 5%

CO2 atmosphere, cells were fixed for 2 min with

methanol, dyed for 20 min with 1% crystal violet, and the numbers

of colonies (at least 50 cells) formed in the whole well were

counted.

Determination of active caspase-3, -8 and

-9

The activities of caspase-3, -8 and -9 were measured

using caspase-3, -8 and -9 Colorimetric Assay kits (Keygen BioTech,

Nanjing, China), respectively, to determine the potential role of

the caspase-3, -8 and -9 proteases in the Bmi-1-knockdown-induced

apoptosis. Briefly, 1×106 cells 72 h after transfection

were lysed at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant were then transferred

to a clean microfuge tube, and protein concentration was assayed.

Subsequently, 50 μl of 2× reaction buffer and 5 μl of caspase-3, -8

and -9 substrates were added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C

for 4 h in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm on a

multidetection microplate reader (Synergy™ HT; Bio-Tek, Winooski,

VT). The activities of caspase-3, -8 and -9 were determined by

calculating the ratio of OD 405 nm of the transfected cells to OD

405 nm of the parental cells following the instructions of the

manufacturer.

In vivo tumor model

Six-week-old female athymic nude mice were

subcutaneously injected with 5×106 cells in 0.2 ml of

PBS into the right scapular region. Three groups (five mice each)

of mice were examined. Group 1 was injected with HEp-2 cells alone;

group 2 was injected with HEp-2 cells transfected with scrambled

nucleotide control siRNA (NC-GFP-LV); and group 3 was injected with

HEp-2 cells transfected with Bmi-1 siRNA (Bmi-1-RNAi-LV). Tumor

size was measured every two days using calipers. Tumor volume was

calculated with the formula (L × W2)/2, where L is the

length and W is the width. The mice were sacrificed after three

weeks and the weight of the tumors was measured. The investigation

conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication

No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 10.0 was used for statistical analysis. One-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the significance

between groups. The LSD method of multiple comparisons with

parental and control vector groups was used when the probability

for ANOVA was statistically significant. A P-value of 0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

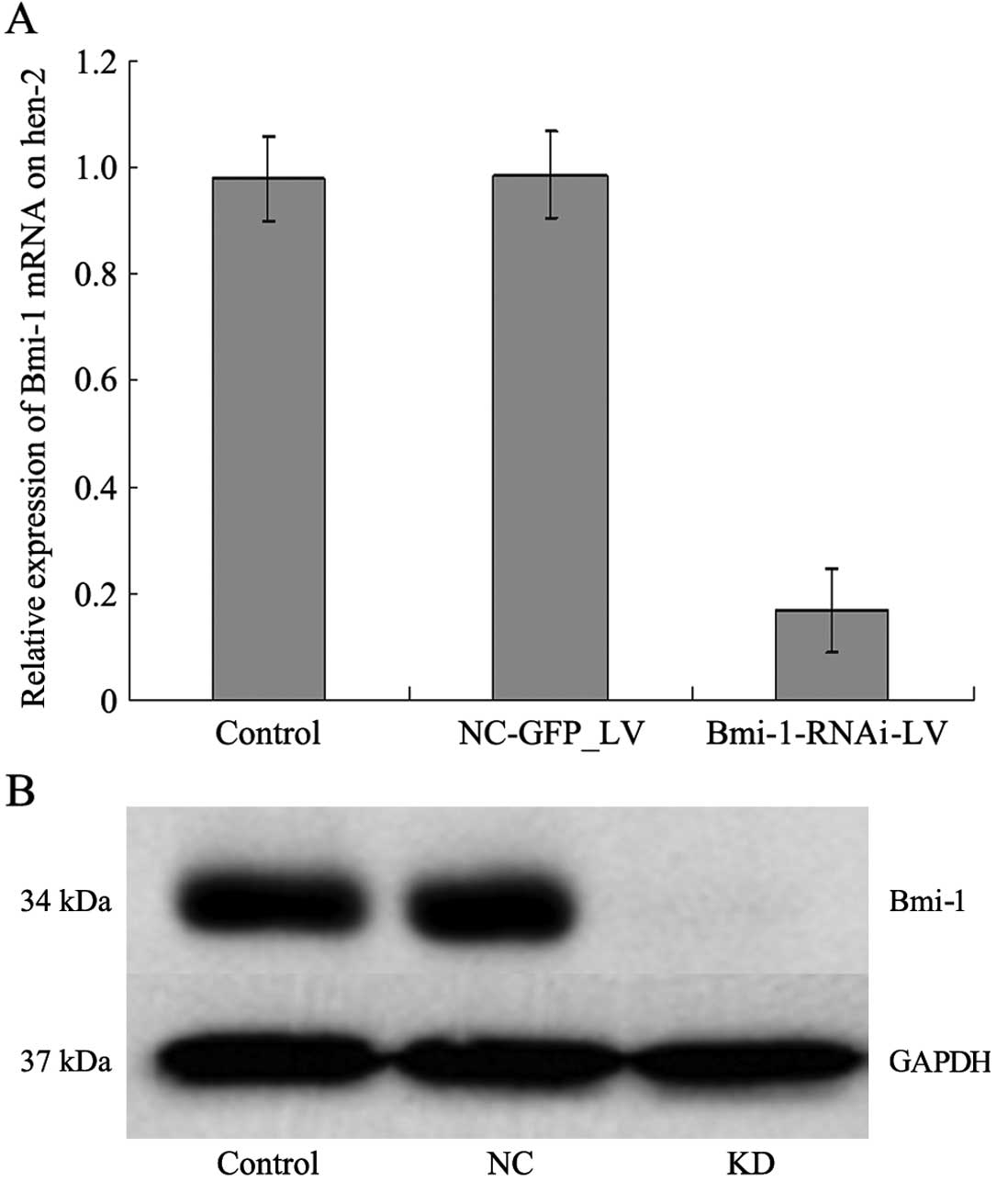

Bmi-1 mRNA and protein expression

Among the four candidate target sequences screened,

the lentiviral vector containing the human Bmi-1 shRNA-expressing

cassette (sequence, 5′-GGAGGAGGTGAATGATAAA-3′) achieved the

greatest efficacy in silencing Bmi-1 expression. This construct was

therefore denoted as Bmi-1-RNAi-LV; the negative control containing

pGCSIL/U6 mock vector only was denoted as NC-GFP-LV. After the

Bmi-1-RNAi-LV construct was transfected into HEp-2 cells, Bmi-1

mRNA expression levels in the transfected cells were compared with

those in the untransfected and control-transfected (NC-GFP-LV)

HEp-2 cells by quantitative RT-PCR. As a result, cells transfected

with Bmi-1-RNAi-LV showed an 80% reduction in the level of Bmi-1

mRNA expression (Fig. 2A). Bmi-1

protein expression was determined by western blot analysis to

further confirm the specificity of Bmi-1-RNAi-LV-mediated Bmi-1

silencing. Bmi-1 protein expression in the cells transfected with

Bmi-1-RNA-LV decreased significantly compared with that of the

control cells (Fig. 2B). These

results indicated that lentivirus-mediated RNAi is an effective

method for modulating Bmi-1 expression in cultured HEp-2 cells.

No significant change (P>0.05) was observed in

the levels of retinoblastoma (Rb) and human telomerase reverse

transcriptase (hTERT) in the cells following transfection with

Bmi-1 siRNA. However, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) levels

increased significantly (P<0.05) and Bcl-2, p14, cyclin D1 and

homeobox A9 (HOXA9) levels decreased significantly (P<0.05) in

the cells treated with Bmi-1 siRNA (Fig. 3).

Proliferation of transfected HEp-2

cells

The siRNA-transfected cells proliferated at a

significantly lower rate compared to the control and parental

cells, as measured by MTT assay (Fig.

4). Cell growth assay was performed, demonstrating a

significant decrease in cell viability in the Bmi-1-RNAi cells

compared with the control cells in a time-dependent manner, and the

highest inhibitory rate was 51.25±2.86% for the HEp-2 cells on day

six (P<0.05). However, no significant difference in cell

proliferation was observed between the negative control and the

control group in each cell line (P>0.05).

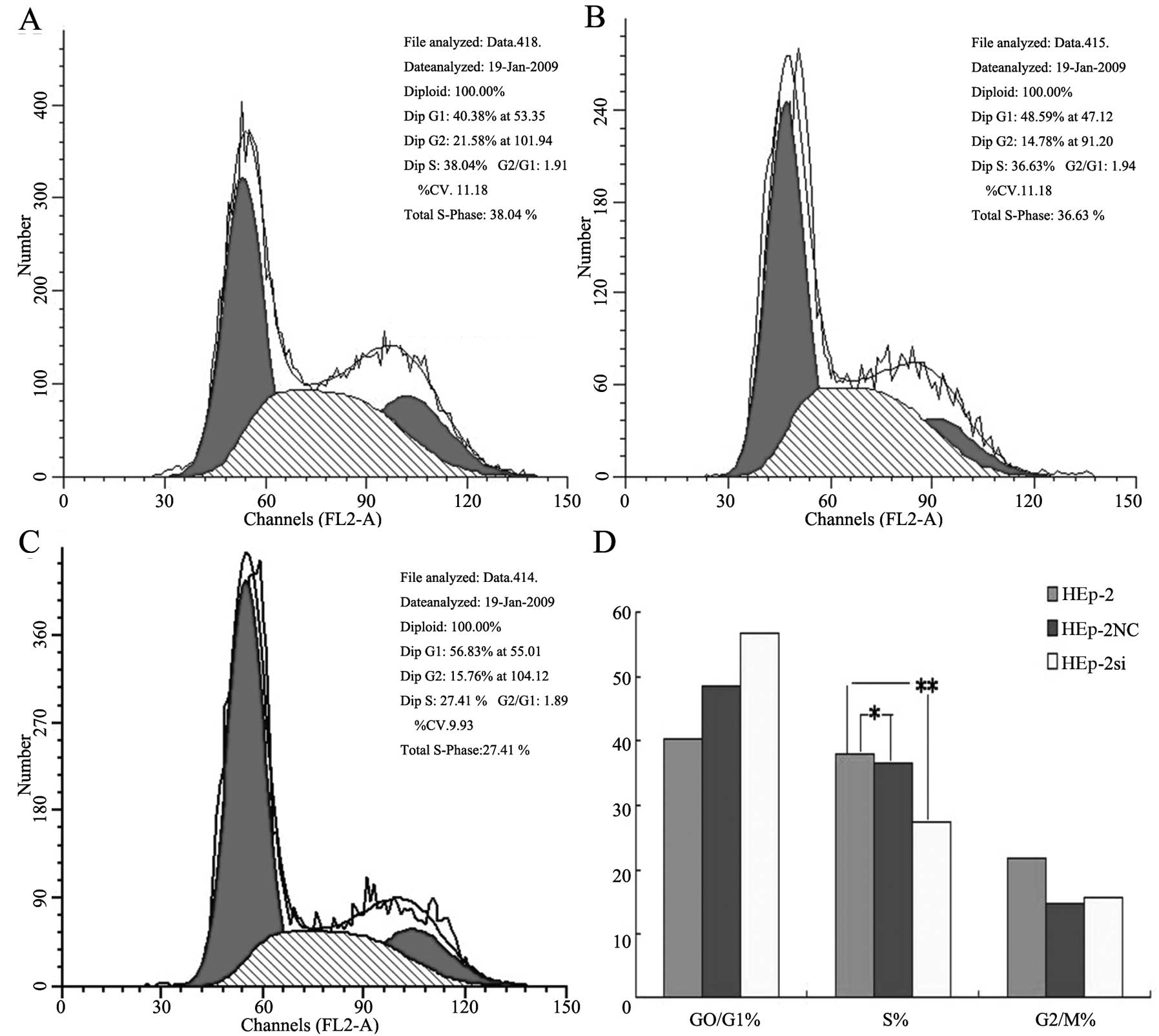

Inhibition of Bmi-1 expression increases

cell apoptosis

Cell cycle distribution analysis (Fig. 5) indicated that significant

changes were observed in the Bmi-1-RNAi cells, compared with the

control group cells; several cells were blocked in the G0/G1 phase

by 87.5±2.5% (P<0.05) and reduced in the G2/M phase by 3.5±1.3%

(P<0.05), whereas no significant difference was observed in the

cell cycle distribution between the negative control and control

group (P>0.05).

The cells were stained with Annexin V and PI to

further evaluate the induction of apoptosis. The proportion of

Annexin V stained cells to the total Bmi-1 siRNA-transfected cells

was increased (Fig. 6). A small

amount of necrotic cells stained with PI, but not Annexin V, was

also observed. The apoptotic rates in the experimental group after

the cells were treated with RNAi were 21.83, 8.59 and 6.38% in the

Bmi-1-RNAi-LV, NC-GFP-LV group and control group, respectively. The

apoptotic rate of HEp-2 cells increased to 21.83% (P<0.05)

following treatment with Bmi-1-RNAi-LV, whereas no obvious cell

apoptosis was observed in the negatuve conrol and control group

(P>0.05). These results indicated that anti-Bmi-1 siRNA induced

HEp-2 cells apoptosis.

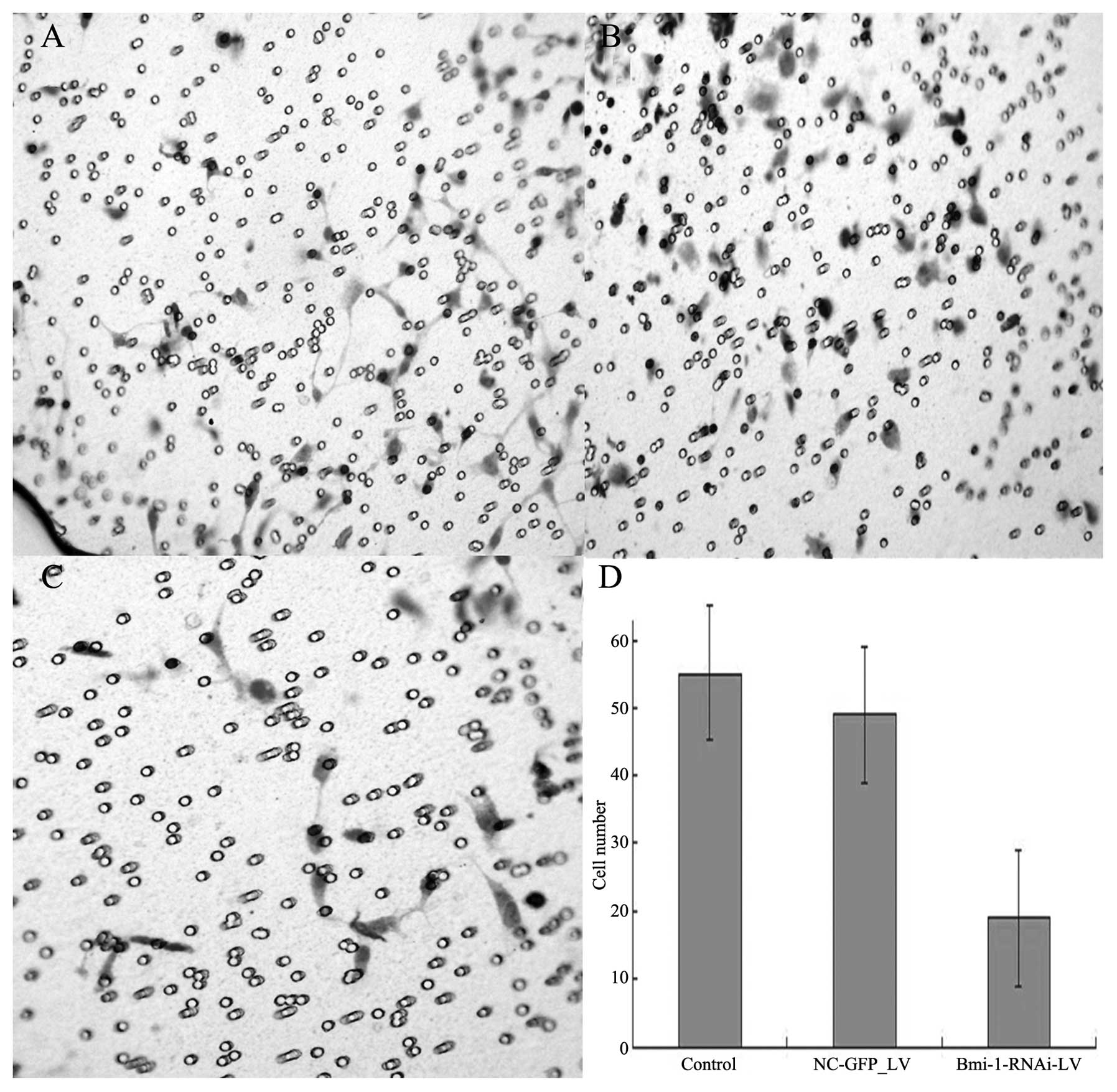

Boyden chamber assay and wound healing

assay

After the cultivation of the cells for 48 h,

invasions of 18.5±3.8, 55.6±11.3, and 49±13.5 cells/field of view

through the porous Transwell membranes were observed for the

Bmi-1-RNAi-LV, control and NC-GFP-LV group, respectively (t=12.62,

P<0.01) (Fig. 7).

HEp-2 cells transfected with Bmi-1 siRNA had a

slower wound-healing rate compared with the cells transfected with

scrambled nucleotide control siRNA (NC-GFP-LV) (0.38±0.046:1,

P<0.05) (Fig. 8).

Activation of caspase-3, -8 and -9 via

inhibition of Bmi-1 expression

The activities of caspase-3, -8 and -9 in the HEp-2

cells transfected with Bmi-1 siRNA or with negative RNA were

examined (Fig. 9) by colorimetric

assay. In addition to executioner caspase-3, initiator caspase-8

and -9 are also important for apoptosis. The ratio of OD 405 nm of

the transfected cells to OD 405 nm of the scrambled nucleotide

control siRNA cells was calculated. The OD value of caspase-3 and

-9 was approximately 4 and that of caspase-8 was approximately

2.

Downregulation of Bmi-1 inhibits the

tumorigenicity of HEp-2 cells in vivo

Tumor volume was measured every two days until the

mice were sacrificed on day 21. The mice in group 3 had

substantially smaller tumors compared to the mice in the other two

groups (Fig. 10). At the time of

sacrifice, the tumor volume for the mice injected with

Bmi-1-RNAi-LV was 274.68±154.79 mm3 compared with

664.31±246.30 mm3 for the mice injected with HEp-2 cells

(P=0.003) or 643.67±270.12 mm3 for the mice in the

negative control group (P=0.008). In addition, the mean tumor

weight at the end of the experiment was significantly lower in the

Bmi-1-RNAi-LV group (0.58±0.12 g) compared to that in the negative

control (1.15±0.19 g, P=0.005) or the control group (0.98±0.20 g,

P=0.007).

TUNEL assay

TUNEL assay showed that groups 1 and 2 had scattered

apoptotic cells, whereas group 3 showed a large number of apoptotic

cells (x400) compared with the HEp-2 and negative control group

(P<0.05) (Fig. 11).

Western blot analysis

The western blot analysis results showed the

significant inhibitory effect of Bmi-1 lentiviral-mediated RNAi on

Bmi-1, cyclin D1 and p14 protein expression. Bmi-1, cyclin D1 and

p14 protein expression in the HEp-2 cells transfected with Bmi-1

lentiviral-mediated RNAi was significantly decreased (Fig. 12).

Discussion

Laryngeal carcinoma accounts for 1 to 5% of all

tumors, and is the second most common cancer of the respiratory

system (next to lung cancer). It is also the second most common

epithelial malignancy in the head and neck region (next to

nasopharyngeal cancer), and accounts for 7.9 to 35% of all ear,

nose and throat (ENT) malignancies (23). If treated early, the prognosis of

laryngeal carcinoma is good, with a five-year survival rate of 90%

and the possibility of retaining laryngeal functions (24). However, the prognosis of

late-stage laryngeal carcinoma is poor due to tumor invasion and

metastasis. The five-year survival rate is below 60%, and patients

usually succumb to the diseased due to local recurrence, neck lymph

node recurrence, or distant metastasis (25,26). The molecular mechanisms behind the

development and progression of laryngeal carcinoma are poorly

understood.

Bmi-1 plays a critical role in the immortalization

of normal epithelial cells and early malignant transformation, as

well as in the maintenance of the self-renewal of stem cells.

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins play an important role

as epigenetic gene silencers during development (27). In addition to their role in

development, these proteins have been reported to be overexpressed

in a variety of human cancers, such as malignant lymphomas and

various solid tumors (28). In

particular, Bmi-1 is overexpressed in a number of malignancies,

such as mantle cell lymphoma (6),

B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (9), myeloid leukemia (8), non-small cell lung cancer (29), colorectal cancer (10), as well as breast and prostate

cancers (16,12). In addition, we recently reported

that Bmi-1 is also overexpressed in laryngeal carcinoma (30). Our present study demonstrates that

a significant difference in Bmi-1 expression at both the protein

and mRNA level exists between laryngeal carcinoma cells and the

adjacent normal laryngeal tissue.

In the present study, we designed and constructed a

siRNA recombinant expression vector targeting Bmi-1 to investigate

its effect on laryngeal carcinoma cell proliferation. Cell

proliferation was significantly inhibited after the cells were

treated with RNAi. We demonstrate that lentiviruses can efficiently

deliver Bmi-1 siRNAs into HEp-2 cells and that the transfection of

Bmi-1 shRNA virtually eliminates Bmi-1 protein expression,

indicating that siRNA sequences targeting Bmi-1 may be a potential

therapeutic strategy for the gene therapy of LSCC. Previous studies

have reported that the downregulation of Bmi-1 by the

adenovirus-mediated delivery of Bmi-1 siRNA reduces the invasion,

angiogenesis and metastasis of lung cancer cells (31). Moreover, the adenovirus-mediated

expression of Bmi-1 siRNA in human lung xenografts in vivo

has been shown to result in increased immunostaining of Fas, Fas-L,

cleaved Bid and TIMP-3, which in turn promotes apoptosis in lung

cancer (32).

The initiation and progression of laryngeal

carcinoma involve a series of genetic events, including the

activation of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressors

(33).

The regulatory mechanism of the PcG proteins relies

upon epigenetic modifications of specific histone tails that are

inherited through cell division (34,35). Bmi-1 is a member of the PcG

family, thus, Bmi-1 overexpression can repress the p16Ink4a

(CDKN2A) and p19Arf targets (10,15). In the absence of p16Ink4a, the

cyclin D/Cdk4/6 complex can phosphorylate pRb, allowing the

E2F-dependent transcription, which leads to cell cycle progression

and DNA synthesis. Bmi-1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts

overexpress the INK4a/ARF locus-encoded genes, CDKN2A and p19ARF

(mouse homologue of human p14ARF), and undergo premature senescence

in culture (36).

Previous studies using in vivo mouse and

in vitro cell culture models have shown that Bmi-1 regulates

the expression of the INK4A/ARF locus, which encodes two

important tumor suppressors, namely, p16INK4A and p19ARF (p14ARF in

humans) (36,37). Bmi-1 can potentially regulate the

p16-pRb and p53-p21 pathways of senescence by downregulating

p16INK4A and p19ARF (38).

PTEN regulates multiple signal transduction

pathways, involved in the inhibition of proliferation and

migration. PTEN exerts a variety of tumor suppressive effects, on

various downstream signaling pathways, such as the pI3K/AKT

pathway, and regulates gene transcription and protein translation,

inducing apoptosis and promoting cell cycle arrest.

Bmi-1 expression is regulated by the cell cycle and

the highest expression is observed in the G2/M phase (39). Our data showed that suppressing

the expression of Bmi-1 in HEp-2 cells significantly inhibits cell

proliferation and induces spontaneous cell apoptosis and G0/G1 cell

cycle arrest. These results are in accordance with thos form

previous studies on esophageal carcinoma cells (40) and cervical carcinoma cells. These

data suggest that Bmi-1 plays an important role in the development

of laryngeal carcinoma.

The suppression of Bmi-1 expression by

lentiviral-mediated RNAi, induces cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase

of the cell cycle and promotes apoptosis. Thus, this method of

suppressing Bmi-1 expression which leads to cell growth inhibition

and the induction of apoptosis, in turn reduces the number of

proliferating cells, abnormal proliferation and suppresses the

growth of laryngeal carcinoma cells; thus it has a significant

therapeutic effect.

In the present study, BALB/c nude mice were injected

with HEp-2 laryngeal carcinoma cells transfected with Bmi-1 siRNA

(Bmi-1-RNAi-LV). The results showed that both the average tumor

weight and volume were significantly lower in the

Bmi-1-RNAi-LV-treated group than those in the control group. The

study by Abdouh showed that downregulating the expression of Bmi-1

by lentiviral shRNA led to the decline of colony formation and

glioma growth both in vitro and in vivo (41), which is consistent with our

findings.

Our results demonstrated that Bmi-1 gene silencing

cannot eliminate the tumor completely, suggesting that Bmi-1 is not

the only protease involved in the invasion and growth of LSCC. The

functions of Bmi-1 associated with stem cells in head and neck

cancer have not yet been fully elucidated. It is also important to

investigate the associated genes and signal transduction pathways

in order to effectively contribute to the gene targeted therapy of

head and neck tumors, thus increasing the possibility of developing

a more potent therapy for head and neck tumors.

We directly approached the important role of Bmi-1

in the invasion and growth of LSCC by analyzing the effects of

stable Bmi-1 silencing by recombinant lentivirus-mediated shRNA. To

our knowledge, we demonstrate for the first time the inhibition of

Bmi-1 expression by lentivirus-mediated shRNA, suggesting that

Bmi-1 may be a candidate gene for the gene targeted therapy of

human LSCC.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from the

Science and Technology Project of Shanxi Province (no.

2010D40).

References

|

1

|

Marioni G, Marchese-Ragona R, Cartei G,

Marchese F and Staffieri A: Current opinion in diagnosis and

treatment of laryngeal carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 32:504–515.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Papadas TA, Alexopoulos EC, Mallis A,

Jelastopulu E, Mastronikolis NS and Goumas P: Survival after

laryngectomy: a review of 133 patients with laryngeal carcinoma.

Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 267:1095–1101. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sun YN, Liu M, Yang B, Li B and Lu J: Role

of siRNA silencing of MMP-2 gene on invasion and growth of

laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

265:1385–1391. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhao JX and Xie XL: Regulation of gene

expression in laryngeal carcinama by microRNAs. Int J Pathol Clin

Med. 32:222–225. 2012.

|

|

5

|

Srivastava R: Apoptosis, Cell Signaling,

and Human Diseases Molecular Mechanisms. 1. Humana Press; Totowa:

2007

|

|

6

|

Bea S, Tort F, Pinyol M, et al: BMI-1 gene

amplification and overexpression in hematological malignancies

occur mainly in mantle cell lymphomas. Cancer Res. 61:2409–2412.

2001.

|

|

7

|

Bhattacharyya J, Mihara K, Ohtsubo M, et

al: Overexpression of BMI-1 correlates with drug resistance in

B-cell lymphoma cells through the stabilization of survivin

expression. Cancer Sci. 103:34–41. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sawa M, Yamamoto K, Yokozawa T, et al:

BMI-1 is highly expressed in M0-subtype acute myeloid leukemia. Int

J Hematol. 82:42–47. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kimura M, Takenobu H, Akita N, et al: Bmi1

regulates cell fate via tumor suppressor WWOX repression in

small-cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 102:983–990. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kim JH, Yoon SY, Kim CN, et al: The Bmi-1

oncoprotein is overexpressed in human colorectal cancer and

correlates with the reduced p16INK4a/p14ARF proteins. Cancer Lett.

203:217–224. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Glinsky GV, Berezovska O and Glinskii AB:

Microarray analysis identifies a death-from-cancer signature

predicting therapy failure in patients with multiple types of

cancer. J Clin Invest. 115:1503–1521. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Song W, Tao K, Li H, et al: Bmi1 is

related to proliferation, survival and poor prognosis in pancreatic

cancer. Cancer Sci. 101:1754–1760. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yao X, Wang X, Zhang S and Zhu H: Effects

of Bmi-1 RNAi gene on laryngeal carcinoma Hep-2 cells. Lin Chung Er

Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 26:550–557. 2012.(In

Chinese).

|

|

14

|

Kang MK, Kim RH, Kim SJ, et al: Elevated

Bmi-1 expression is associated with dysplastic cell transformation

during oral carcinogenesis and is required for cancer cell

replication and survival. Br J Cancer. 96:126–133. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Song LB, Zeng MS, Liao WT, et al: Bmi-1 is

a novel molecular marker of nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression

and immortalizes primary human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells.

Cancer Res. 66:6225–6232. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Glinsky GV: Death-from-cancer signatures

and stem cell contribution to metastatic cancer. Cell Cycle.

4:1171–1175. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hoenerhoff MJ, Chu I, Barkan D, et al:

BMI1 cooperates with H-RAS to induce an aggressive breast cancer

phenotype with brain metastases. Oncogene. 28:3022–3032. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xu CR, Lee SS, Ho C, et al: Bmi1 functions

as an oncogene independent of Ink4A/Arf repression in hepatic

carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 7:1937–1945. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, et

al: Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in

cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 411:494–498. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mittal V: Improving the efficiency of RNA

interference in mammals. Nat Rev Genet. 5:355–365. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Moffat J and Sabatini DM: Building

mammalian signalling pathways with RNAi screens. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 7:177–187. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim DH and Rossi JJ: Strategies for

silencing human diseaseusing RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet.

8:173–184. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang XZ and Wang JB: Practical

otolaryngology. People’s Medical Publishing House; Beijing: pp.

502–503. 1998

|

|

24

|

Tu Gy, Tang PZ and Jia CY:

Horizontovertical laryngectomy for supraglottic carcinoma.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 117:280–286. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sessions DG, Lenox J, Spector GJ, et al:

Management of T3N0M0 glottic carcinoma: therapeutic outcomes.

Laryngoscope. 112:1281–1288. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu YZ, Tang PZ, Qi YF and Xu Z: The

management of stomal recurrence after laryngectomy. Zhonghua Er Bi

Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 37:380–383. 2002.(In Chinese).

|

|

27

|

Ringrose L and Paro R: Epigenetic

regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group

proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 38:413–443. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Raaphorst FM: Deregulated expression of

Polycomb-group oncogenes in human malignant lymphomas and

epithelial tumors. Hum Mol Genet. 14:R93–R100. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kikuchi J, Kinoshita I, Shimizu Y, et al:

Distinctive expression of the polycomb group proteins Bmi1 polycomb

ring finger oncogene and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in nonsmall

cell lung cancers and their clinical and clinicopathologic

significance. Cancer. 116:3015–3024. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yao XB, Wang XX, Zhang SQ, Yan LY and Zhu

HL: Association of Bmi-1 mRNA overexpression with differentiation,

metastasis and prognosis of laryngocarcinoma. Xi’An Jiaotong Daxue

Xuebao. 32:246–249. 2011.(In Chinese).

|

|

31

|

Wang YX, Wei YM, Wang XH and Zhu XY:

Construction of eukaryotic expression vector targeting Bmi-1 and

its influences on proliferation of SW480 cells. Xian Dai Sheng Wu

Yi Xue Jin Zhan. 9:2270–2272. 2009.(In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Wang ZX, Lu BB, Yang JS, Wang KM and De W:

Adenovirus-mediated siRNA targeting c-Met inhibits proliferation

and invasion of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells. J Surg Res.

171:127–135. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li PH, Wang HJ, Liu W and Xu XG: PRDM1

gene expression in laryngeal carcinoma and its clinical

significance. Head Neck Surg. 24:179–180. 2010.

|

|

34

|

Pirrotta V: Polycombing the genome: PcG,

trxG, and chromatin silencing. Cell. 93:333–336. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Orlando V: Polycomb, epigenomes, and

control of cell identity. Cell. 112:599–606. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jacobs JJ, Kieboom K, Marino S, Depinho RA

and van Lohuizen M: The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1

regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a

locus. Nature. 397:164–168. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Itahana K, Zou Y, Itahana Y, et al:

Control of the replicative life span of human fibroblasts by p16

and the polycomb protein Bmi-1. Mol Cell Biol. 23:389–401. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dimri GP: What has senescence got to do

with cancer? Cancer Cell. 7:505–512. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xu Z, Liu H, Lv X, Liu Y, Li S and Li H:

Knockdown of the Bmi-1 oncogene inhibits cell proliferation and

induces cell apoptosis and is involved in the decrease of Akt

phosphorylation in the human breast carcinoma cell line MCF-7.

Oncol Rep. 25:409–418. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu WL, Guo XZ, Zhang LJ, et al:

Prognostic relevance of Bmi-1 expression and autoantibodies in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 10:4672010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Abdouh M, Facchino S, Chatoo W, et al:

BMI1 sustains human glioblastoma multiforme stem cell renewal. J

Neurosci. 29:8884–8896. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|