Introduction

Vulvar melanoma is the second most common vulvar

cancer with an incidence of 0.1 per 100,000 individuals, presenting

typically in post-menopausal women (1,2).

Patients with vulvar melanoma, due to the lack of body awareness,

false modesty and neglect, usually present with the disease at a

late stage and have a poor overall prognosis, with reported 5-year

survival rates ranging from 8 to 61% (3–10).

This is unlike cutaneous melanomas where, as a result of increased

public and clinical awareness, many patients are now diagnosed at

an early stage.

The aetiology of vulvar melanoma is poorly

understood but is believed to arise de novo, that is, to

develop from the malignant transformation of a single junctional

melanocyte in situ (4). A

genetic basis is suspected, which may explain why caucasions have a

3-fold higher incidence rate than individuals of African descent

(11) and why individuals of

African descent have a 2-fold shorter median survival than

caucasions (12). Activating

c-KIT mutations have been found in patients with vulvar melanoma

(13,14). By contrast, as previously

demonstrated, gene mutations for cutaneous melanomas were

irrelevant in vulvar melanomas (BRAF, NRAS), indicating that these

two diseases have a different origin (13,15).

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is also suspected to cause

vulvar melanoma, and LS has indeed been reported with vulvar

melanoma in 6 cases (17–20). Whereas 5 childhood vulvar

melanomas cases have been reported, only 1 among thousands of adult

vulvar melanoma patients have been reported (18). The mechanisms involved, however,

are not clear. LS, itself an inflammatory dermatosis of unknown

origin presenting with whitening of the skin and pruritus (21), is the most common precursor of

HPV-negative squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, where the

postulated pathogenesis is a ‘scar cancer’ similar to Margolin’s

ulcer (22,23). The difficulty of distinguishing

vulvar melanoma in the setting of LS from benign pigmented lesions

of the genitals is acknowledged (24).

There is no consensus regarding the adequate staging

system and the treatment for vulvar melanomas. The standard FIGO

staging, as used for squamous cell carcinoma, is not satisfactory.

In vulvar melanomas, lesions are usually much smaller and prognosis

is related to depth rather than diameter. For this reason, Breslow

staging, which takes into account the depth of tumour rather than

its size, seems to be most adequate and until today the best

predictor of prognosis (25–29). This was also confirmed by a recent

American study with 85 cases of melanomas of the female genitalia

(30): a higher Breslow depth was

associated with declining survival, whereas other histopathological

features, such as ulcerations, increasing mitotic index and the

presence of atypical melanocytic hyperplasia were not associated

with a significant survival difference. Three basic histotypes

(superficial spreading melanoma, mucosal lentiginous melanoma and

nodular melanoma) have been described with varying incidence rates

(5,6,9,31).

It is an ongoing search for reliable histological

features that allow the prognosis of vulvar melanoma; however, the

majority of studies (small case series and retrospective reviews)

have delivered inconclusive results. Thus, we performed a) a

comprehensive literature review, b) a clinicopathological review of

33 vulvar melanoma cases of an Australian cohort to identify

potential histopathological predictors of outcome, and c)

immunohistochemistry for c-KIT expression in a respective tissue

microarray.

Patients and methods

Comprehensive literature review

The systematic literature review was performed using

the online websites, PubMed, Medline and Cochrane for the key words

‘vulva melanoma’, ‘mucosal melanoma’, ‘melanoma’, ‘melanomas’,

‘vulvar’, ‘vulva’ and ‘vulvar neoplasm’. The retrieval was limited

from 1990 to 2012 and included epidemiological studies, literature

reviews, retrospective series, prospective series, meta-analyses

and molecular analyses. Studies with <10 patients were excluded,

as were individual case reports. Studies were reported as to their

year of publication, the number of enrolled patients, type of

study, mean age of patients, 5-year overall survival, and study

results and clinicopathological predictors of outcome (Table I).

| Table ILiterature review. |

Table I

Literature review.

| Author/(Refs.) | Year | Vulvar melanoma

patients (n) | Melanoma

location | Study type | Mean patient age

(years) | 5-year OS (%) | Results and

predictors of outcome |

|---|

| Bradgate et

al (3) | 1990 | 50 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | N/A | 35 | Clinical stage,

patient age, ulceration, cell type, mitotic rate |

| Trimble et

al (32) | 1992 | 80 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 58.5 | 60 | Extent of vulva

surgery not relevant |

| Tasseron et

al (33) | 1992 | 30 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 63.8 | 56 | Ulceration |

| Piura et al

(34) | 1992 | 18 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | N/A | 28.6 | Positive inguinal

lymph nodes not relevant |

| Ragnarsson-Olding

et al (35) | 1993 | 219 | Vulva and other

mucosal melanoma | Epidemiological

study | 75 | 35 | Decrease in

age-standardized incidence in Sweden |

| Look et al

(36) | 1993 | 16 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 59 | N/A | Depth >1.75 mm

predicts recurrence within 24 months |

| Phillips et

al (37) | 1994 | 71 | Vulva | Prospective

series | 71–80 | 43.9 | AJCC staging,

Breslow’s depth |

| Dunton et al

(38) | 1995 | N/A | N/A | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Breslow’s depth,

lymph node dissection |

| Scheistroen et

al (31) | 1995 | 75 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 67 | 46 | Tumour localization

clitoris, DNA ploidy, positive inguinal lymph nodes |

| Raber et al

(39) | 1996 | 89 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 55.4 | 36.7 | Breslow’s depth,

Clark’s level, lymph node status |

| Trimble (40) | 1996 | N/A | N/A | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Breslow’s

depth |

| Scheistroen et

al (41) | 1996 | 43 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 64 | 63 | Angioinvasion, DNA

ploidy |

| Strauss (42) | 1997 | N/A | Melanomas | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | p53 mutations |

| Jiveskog et

al (15) | 1998 | N/A | Cutaneous vs.

mucosal melanomas | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | NRAS mutations not

relevant |

| De Matos et

al (43) | 1998 | 30 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 66 | 59 | Regional

metastases |

| Ragnarsson-Olding

et al (5) | 1999 | 219 | Vulva | Epidemiological

study | N/A | 47 | Breslow’s depth,

ulceration, amelanosis |

| Larsson et

al (44) | 1999 | 19 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | N/A | 23 | Stage |

| Creasman et

al (45) | 1999 | 569 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 66 | 62 | AJCC stage |

| Raspagliesi et

al (46) | 2000 | 40 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 58 | 48 | Positive inguinal

lymph nodes |

| Verschraegen et

al (9) | 2001 | 51 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 54 | 27 | AJCC stage,

Breslow’s depth |

| Irvin et al

(8) | 2001 | 14 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 58 | 42 | Margins, inguinal

lymphadenectomy |

| Ragnarsson-Olding

et al (47) | 2002 | 22 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | | | p53 mutations |

| De Hullu et

al (48) | 2002 | 33 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 69 | 52 | Sentinel

lymphadenectomy |

| Finan and Barre

(49) | 2003 | N/A | N/A | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Age, AJCC

stage |

| Ragnarsson-Olding

(2) | 2004 | 1,442 | Vulva | Meta-analysis | N/A | N/A | Breslow’s depth,

ulceration, amelanosis, angioinvasion, DNA ploidy |

| Ragnarsson-Olding

et al (7) | 2004 | 17 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | p53 protein levels

not relevant |

| Harting and Kim

(50) | 2004 | 11 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 59 | 10 | Chemotherapy |

| Wechter et

al (51) | 2004 | 21 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 58 | N/A | Sentinel

lymphadenectomy |

| Edwards et

al (52) | 2004 | 8 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | BRAF mutations not

relevant |

| Dahlgren et

al (53) | 2005 | 7 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | HPV not

relevant |

| Stang et al

(54) | 2005 | 102 | Vulva | Epidemiological

study | 70 | N/A | No change in

incidence rate |

| Rouzier et

al (55) | 2005 | N/A | N/A | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Wide local excision

with tumour-free margins, sentinel lymphadenectomy |

| Lundberg et

al (56) | 2006 | 7 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | HSV not

relevant |

| Sugiyama et

al (10) | 2007 | 644 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 68 | 61 | Age, stage,

positive inguinal lymph nodes |

| Dhar et al

(57) | 2007 | 26 | Vulva | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Sentinel

lymphadenectomy |

| Giraud et al

(58) | 2008 | 7 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | Polyomaviruses not

relevant |

| De Simone et

al (59) | 2008 | 11 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 53 | 50 | N/A |

| Hu et al

(11) | 2010 | 324 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | N/A | N/A | Ethnicity |

| Moan et al

(60) | 2010 | N/A | Vulva | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Sun exposure not

relevant |

| Trifiro et

al (61) | 2010 | 12 | Vulva | Prospective

study | 59 | N/A | Sentinel

lymphadenectomy not relevant |

| Terlou et al

(62) | 2010 | N/A | N/A | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | ABCDE and punch

biopsy are useful in diagnosis |

| Baiocchi et

al (63) | 2010 | 11 | Vulva | Retrospective

series | 64.8 | 10 | Sentinel

lymphadenectomy not relevant |

| Ragnarsson-Olding

(64) | 2011 | N/A | N/A | Literature

review | N/A | N/A | Sun exposure not

relevant |

| Omholt et al

(13) | 2011 | 23 | Vulva | Molecular

analysis | N/A | N/A | KIT mutations,

RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways activated |

| Tcheung et

al (30) | 2012 | 85 | Genitals/vulva | Retrospective

series | 60.5 | 50.7 | N/A |

| Schoenewolf et

al (14) | 2012 | 16 | Genitals/vulva | Retrospective

series/molecular analysis | 61.9 | N/A | c-KIT expression

and mutations; pERK |

| Heinzelmann-Schwarz

(this study) | | 33 | Vulva | Literature review,

retrospective series, molecular analysis | 67.5 | N/A | At least one of

these pathological features: satellitosis, in-transit metastases,

dermal mitosis, LVSI; strong c-KIT expression, lateral margin >1

cm |

Clinicopathological review of our study

cohort

Upon obtaining ethical approval and informed

consent, we identified and enrolled 33 patients with vulvar

melanoma at the Gynaecological Cancer Centre of the Royal Hospital

for Women, Sydney (20 patients, incepted 1987) and the

Gynaecological Cancer Centre of John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle (13

patients, incepted 1991). The following information was retrieved

from the charts of the patients: age

(diagnosis/menopause/relapse/death), duration of symptoms (months),

menopausal status, family history of melanoma, location of

melanoma, mode of detection, palpable groin nodes, lymph nodes

removed/positive, CT scan results, Breslow’s depth, type of

surgery, chemotherapy/immunotherapy/radiotherapy (number of

sessions and dose), treatment side-effects, site/location of

recurrence, cause of death, and relapse-free and overall

survival.

Characteristics which were assessed included

diagnosis, pathogenic type (superficial spreading, mucosal

lentiginous melanoma, other), predominant cell type (epithelioid,

spindle or other), ulcerations, Breslow’s depth, tumour

infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS), regression (dermal fibrosis,

lymphocytic infiltrate and, in cases of pigmented melanomas,

melanophages), lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), satellitosis

(discrete tumour nests >0.05 mm in diameter, separated from

invasive tumour by ≥0.3 mm) and in-transit metastases (>20 mm

from invasive tumour), margins (involved by in situ or

invasive melanoma), adjacent abnormal melanocytic proliferation and

LS.

c-KIT immunohistochemistry of tissue

microarrays

An independent, blinded pathological review of all

haematoxylin and eosin slides was performed by a pathologist

specialised in vulvar pathology (Dr J.P. Scurry). These slides

where marked for vulvar melanoma and two 1-mm cores were

transferred onto a tissue microarray, using the ATA-100 Advancer

Tissue Arrayer (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). Cores

also included control tissues from negative inguinal lymph nodes

that were surgically sampled. Immunohistochemistry was performed in

the Bond™-X System (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) using the

polyclonal rabbit Anti-human CD117 antibody (c-KIT; Dako,

Carpinteria, CA, USA) at a 1:400 dilution followed by secondary

detection with the Bond™ Polymer Refine Detection kit combining

anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies (Leica Biosystems). Prior to

staining, antigen retrieval was performed at 95°C for 15 min in the

PT Link (Dako) using the EnVision™ FLEX target retrieval solution,

low pH (50×; Dako), followed by a water wash. Evaluation of the

intensity of c-KIT cytoplasmic and membrane protein expression was

performed by two researchers independently and consensus was

reached. For the purpose of this analysis either cytoplasmic or

membrane staining of 3+ intensity was taken as strong c-KIT

expression.

Statistical analysis

The clinicopathological data were collected in an

in-house research database based on ACCESS (Microsoft Windows, USA)

and analysed with SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc.,

Cary, NC, USA). Mean values with standard deviation and range were

generated for longitudinal datasets and nominal data were presented

as percentages. Potential risk factors for relapse and mortality

were assessed through Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional

hazards models. As the number of cases was limited, the

significance of each hazard ratio (HR) was primarily assessed by

their effect size as p-values alone were likely to miss important

results.

Results

Comprehensive literature review:

predictors of outcome and molecular targets for vulvar

melanoma

Our literature review revealed 46 studies with

>10 patients enrolled with vulvar melanoma (Table I). These studies often combined

both mucosal (including those of the vulva) and cutaneous

melanomas. Out of these 46 studies, 23 were retrospective studies,

with 48.9% comprising the majority of publications in vulvar

melanoma research, 8 studies were literature reviews, 11 comprised

analyses of molecular targets, and 1 was a meta-analysis. No

Cochrane review has been performed to date.

The unequivocal clinical predictors of patient

outcome that were identified were inguinal lymph node status

(either via sentinel or standard lymphadenectomy; 11 studies) and

Breslow’s depth (9 studies). Ambiguous clinical predictors included

tumour ulceration (4 studies), age at diagnosis (3 studies) and DNA

ploidy (3 studies).

Molecular targets suspected to be relevant in

mucosal melanomas have been investigated in 11 studies. Mutations

in mucosal melanomas were found in p53 (3 studies), in

c-KIT (2 studies) and in key kinases of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR-

(1 study) and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK-pathways (1 study). Mutations in

BRAF or NRAS in mucosal melanomas were not found (1

study each) and evidence of the involvement of viral infections

(HPV, HSV, polyomaviruses) in vulvar melanoma was not found either.

Notably, high-throughput transcription profiling experiments on

vulvar melanomas have not been performed to date.

Clinicopathological and immunological

characteristics of our cohort

The clinicopathological and immunological

characteristics of the 33 patients of our cohort are summarized in

Table II. The mean age at

diagnosis was 67.5 years (range, 34–95 years) and was higher

compared to that of the 47 literature review studies (62.2 years;

range, 53–80 years). Patients presented with symptoms for an

average of 28.2 months (range, 2–112 months) and in 72.2% of the

cases detected the lesion themselves. By virtue of the advanced

mean age at diagnosis almost three quarters (73.5%) of our patients

were post-menopausal. The vast majority of the patients (93.8%) did

not have a family history of melanoma. The most common location of

vulvar melanomas was at the labia minora (31.6%) and was multifocal

(26.3%).

| Table IIClinicopathological and

immunohistochemical patient characteristics. |

Table II

Clinicopathological and

immunohistochemical patient characteristics.

| No. | Age | BD | ULC | DM | SAT | ITM | LVSI | LNP | IHC_C | IHC_M | Status |

|---|

| 1 | 51 | 10.5 | Yes | Neg | No | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Alive |

| 2 | 74 | 1.5 | Yes | Neg | No | No | No | 0 | 1.4 | 0.2 | Alive |

| 3 | 53 | 1.15 | No | Neg | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | Alive |

| 4 | 69 | 5 | Yes | Neg | No | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Alive |

| 5 | 84 | 3.5 | Yes | Pos | Yes | No | No | 0 | 2.2 | 2.75 | Alive |

| 6 | 46 | 1 | Yes | Neg | No | No | No | 0 | N/A | N/A | Alive |

| 7 | 62 | 3.1 | Yes | Neg | No | No | No | 0 | 1 | 1 | Alive |

| 8 | 60 | 4 | Yes | Neg | Yes | No | No | 0 | 0.27 | 1.5 | Deceased |

| 9 | 68 | 4.2 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Deceased |

| 10 | 43 | 14 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | 1 | N/A | N/A | Alive |

| 11 | 96 | 6 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | 0 | 2.25 | 1.89 | Deceased |

| 12 | 91 | 7.5 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | 0 | 2.11 | 2.11 | Deceased |

| 13 | 83 | 0 | No | N/A | No | Yes | No | 0 | 0.5 | 0.75 | Deceased |

| 14 | 84 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | N/A | Deceased |

| 15 | 44 | 6 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | N/A | 0.9 | 0.86 | Deceased |

| 16 | 71 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | Deceased |

| 17 | 68 | 3.3 | Yes | Neg | No | No | Yes | 0 | 1.67 | 2.13 | Deceased |

| 18 | 76 | 5.2 | Yes | Neg | No | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Deceased |

| 19 | 50 | 11 | Yes | N/A | No | No | No | 6 | 1 | 1.18 | Alive |

| 20 | 89 | 19.5 | Yes | Pos | No | Yes | Yes | 0 | N/A | N/A | Alive |

| 21 | 73 | 1 | No | Neg | No | No | No | N/A | 1.5 | 2 | Alive |

| 22 | 64 | 28 | Yes | Pos | No | No | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | Deceased |

| 23 | 68 | 7 | Yes | Pos | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.75 | 0 | Deceased |

| 24 | 82 | 7 | N/A | Pos | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 0 | Deceased |

| 25 | 67 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | Deceased |

| 26 | 70 | 10 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | N/A | 1 | 1.78 | Alive |

| 27 | 80 | 3.2 | Yes | Pos | No | No | No | N/A | 1.75 | 2.38 | Alive |

| 28 | 67 | 1 | No | Neg | No | No | No | N/A | 1 | 0.8 | N/A |

| 29 | 94 | 1.7 | Yes | Neg | No | No | No | N/A | 1.83 | 2.17 | Deceased |

| 30 | 34 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.09 | 1.36 | Deceased |

| 31 | 81 | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 2.08 | 0.89 | Alive |

| 32 | 58 | 10 | Yes | Pos | Yes | N/A | No | 0 | 1.42 | 2 | Alive |

| 33 | 48 | 2 | Yes | Pos | No | N/A | No | 1 | 1.6 | 2.44 | Alive |

The majority of patients presented with an advanced

Breslow stage of V (56.3%) and had a mean tumour size of 21.9 mm

(range, 5–50 mm), deep margin of 5.20 mm (range, 0–22 mm) and

lateral margin of 3.9 mm (range, 0–12 mm). Most of our patients

received radical local excision. Of the 4 patients that had

received a radical vulvectomy, 3 had multifocal disease and the

other was treated by an outside consultant. The majority of the

patients (68.8%) underwent at least an unilateral inguino-femoral

lymphadenectomy without any notable side-effects (in particular no

lymphoceles or lymphoedema). For the majority of patients, this was

the only adjuvant treatment received: only 25% received

chemotherapy, 18.2% immunotherapy and 38.9% radiotherapy. Seventy

percent of the patients relapsed, with local and distant metastases

equally common: the most common local recurrence was at the vulva

(30.8%). The median time to relapse was 40 months and to death 44

months. Fifty-five percent of the patients succumbed to the

disease, mostly due to causes related to their disease (90%).

The majority of patients presented with a clinically

or pathologically detected ulceration (53.3% or 88.9%,

respectively) of a large tumour nodule of spindle cell type

(52.9%), with a mean of 7.3 dermal mitoses per mm2

(range, 1–40) and high TILS (58.8%). The majority of the patients

did not have regression (66.5%), satellitosis (88.9%), in-transit

metastases (83.3%), LVSI (88.9%), or LS (88.9%). In our cohort, 3

cases of LS with vulvar melanoma were identified (Table III). In all these patients, LS

was observed with or without melanoma in situ, but always

disappeared beneath the invasive melanoma. No pre-existing nevi

were found, but 2 patients showed large single melanocytes at the

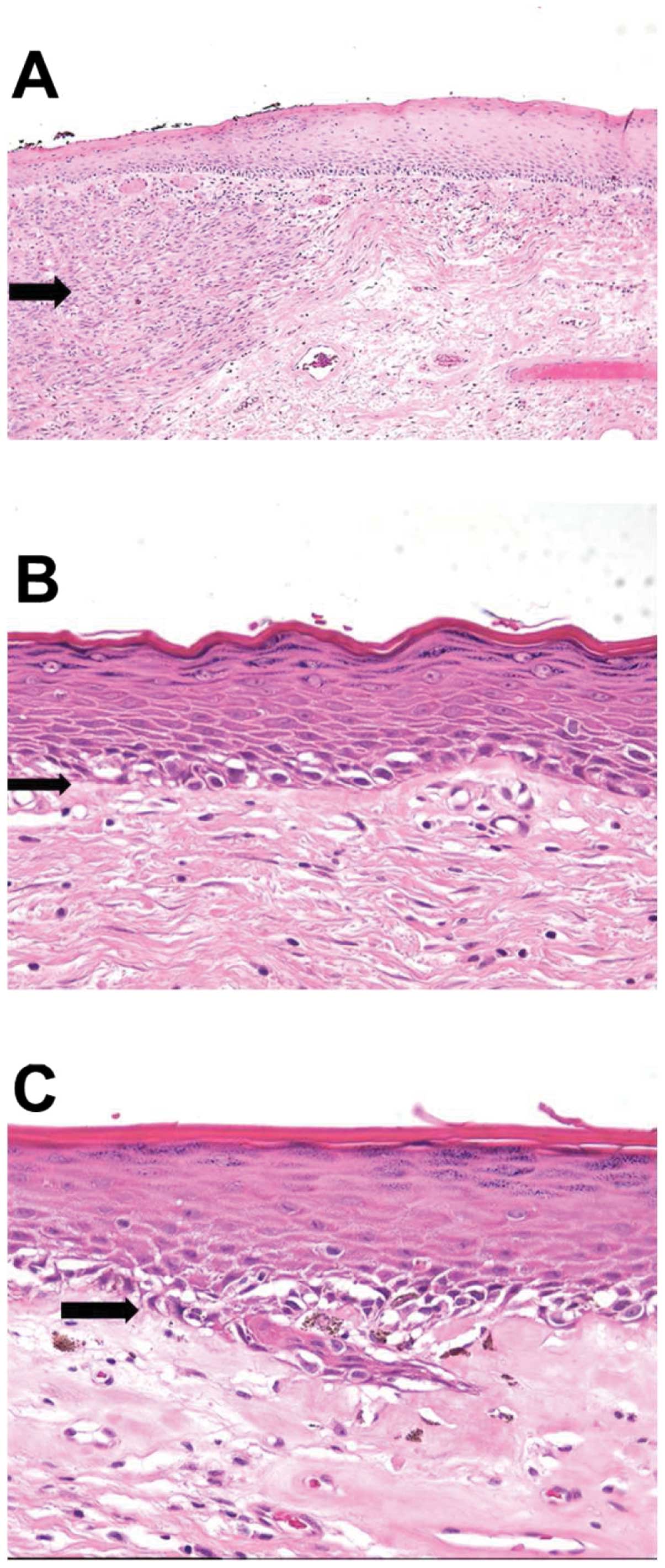

edge of the melanoma in situ. Representative macroscopic

images of a vulvar melanoma specimen and histological examples for

various pathological features are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. An example of a strong c-KIT

expression in an invasive melanoma of the vulva is illustrated in

Fig. 3.

| Table IIIStudies identified in the literature

documenting synchronous lichen sclerosus and vulvar melanoma. |

Table III

Studies identified in the literature

documenting synchronous lichen sclerosus and vulvar melanoma.

| Author/(Refs.) | Year | Age | Depth (mm) | Lymph nodes | Follow-up

(months) | Status |

|---|

| Friedman et

al (16) | 1984 | 14 | 0.7 | Negative | 12 | NED |

| Egan et al

(17) | 1997 | 9 | In situ | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Egan et al

(17) | 1997 | 11 | 0.47 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Carlson et

al (18) | 2002 | 83 | 2.7 | Negative | 21 | NED |

| Hassanein et

al (19) | 2004 | 10 | 0.44 | Negative | 12 | NED |

| Rosamilia et

al (20) | 2006 | 10 | 1 | Positive | 32 | NED |

| De Simone et

al (59) | 2008 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| This study | | 69 | 1 | Negative | 120 | DOD |

| This study | | 84 | 3.5 | Negative | 12 | DOD |

| This study | | 81 | | Negative | 2 | NED |

Predictors of outcome for vulvar melanoma

identified in our cohort

Our study confirmed the known predictive

clinicopathological characteristics Breslow’s depth [relapse-free

survival (RFS): HR=1.08, p=0.049] and lymphadenectomy (RFS:

HR=0.376, p=0.087, Table IV and

Fig. 4A). These were particularly

important in relation to recurrence. No significant results for

positivity of lymph nodes were found in our series, possibly due to

the low numbers of positive lymph nodes. In the presence of a

lateral margin of >10 mm [disease-free survival (DFS): HR=2.7,

p=0.21] and a strong (intensity 3+) c-KIT expression (DFS: HR=1.8,

p=0.49; RFS: HR=3.13, p=0.108; Fig.

3), Breslow’s depth becomes less important as regards the

outcome (Table IV, Fig. 4B).

| Table IVMultivariable analysis of high-risk

features. |

Table IV

Multivariable analysis of high-risk

features.

| A, Relapse-free

survival | | | |

|---|

|

|---|

| Predictor | HR (95% CI) | aHRa (95% CI) | aHRb (95% CI) |

|---|

| Pathological

characteristics | 5.02

(0.62–40.61) | 4.86

(0.58–40.81) | 2.89

(0.35–23.83) |

|

Lymphadenectomy | 0.38

(0.12–1.15) | 0.15

(0.03–0.64) | |

| Cell type | 0.75

(0.26–2.19) | 0.72

(0.23–2.22) | |

| Lateral margin | 1.95

(0.53–7.22) | 1.86

(0.49–7.03) | |

| c-KIT

expression | 2.45

(0.66–9.08) | 3.13

(0.78–12.58) | 2.51

(0.61–10.36) |

| Breslow’s

depth | 1.08

(1.00–1.17) | | 1.12

(1.02–1.22) |

|

| B, Disease-free

survival | | | |

|

| Predictor | HR (95% CI) | aHRa (95% CI) | aHRb (95% CI) |

|

| Pathological

characteristics | | | |

|

Lymphadenectomy | 0.71

(0.19–2.63) | 0.25

(0.06–0.99) | 0.31

(0.04–2.44) |

| Cell type | 0.82

(0.25–2.73) | 0.80

(0.24–2.72) | |

| Lateral margin | 2.72

(0.58–12.88) | 2.67

(0.56–12.76) | 7.32

(0.77–69.86) |

| c-KIT

expression | 1.82

(0.38–8.67) | 1.75

(0.35–8.63) | 3.34

(0.42–26.29) |

| Breslow’s

depth | 1.01

(0.92–1.10) | 0.93

(0.57–1.50) | |

The presence of epithelioid cells within a vulvar

melanoma, even when mixed in combination with spindle or nodular

cells, predicted a better prognosis for these patients (HR=0.82,

p=0.75) (Table IV, Fig. 5A). Of the 3 patients, who

contribute to the plateau in the non-epithelioid curve in the

Kaplan-Meier plot, 2 had a spindle/epithelioid and the other had

another cell type, thus supporting our findings.

Due to our cohort size and the low numbers of

certain pathological characteristics, we looked in a combined

approach at high-risk pathological features, such as satellitosis,

in-transit metastases, LVSI and dermal mitosis. This meant that the

presence of any of these 4 features within a cancer was taken for

the purpose of this analysis as the presence of a high-risk

pathological feature. Using this approach, we found that in the

absence of at least one of these features, none of the patients

died (log-rank test, p=0.088), which had a sensitivity of 100%

(Fig. 5B). As regards recurrence,

the presence of at least one of these pathological features

increased the risk of recurrence from the disease by a factor of 5

(HR=5.02).

Independent predictors of outcome and

c-KIT expression

We modelled the identified predictors of prognosis

with each other in order to identify the degree of correlation

between the predictive parameters. In all models, the strongest

predictors for outcome, both in respect of relapse and survival,

was the absence of any of the pathological high-risk

characteristics, such as satellitosis, in-transit metastases, LVSI

or dermal mitosis.

In combination with the pathological high-risk

characteristics, the strongest predictors for earlier relapse were

c-KIT expression [adjusted HR (aHR)=2.51, Table IVA] and Breslow’s depth

(aHR=1.12, Table IVA). With the

increasing depth of the melanoma, lymphadenectomy presents with a

HR of 6.86 (p=0.011) and Breslow’s depth remains statistically

significant (HR=1.13, p=0.0079). Breslow’s depth, in the presence

of some of the other factors, seems to be more important for

recurrence than DFS. None of the classical adjuvant treatment

options, including immunotherapy showed any benefit in our

study.

When modelled together, the strongest predictors of

earlier death were pathologically high-risk characteristics,

followed by lateral margin (>10 mm, aHR=7.32, Table IVB), a strong c-KIT expression

(aHR=3.34, Table IVB) and

lymphadenectomy (aHR=0.3, Table

IVB). For DFS, Breslow’s depth loses its strong predictive

value when compared to a lateral margin of >10 mm and a strong

c-KIT expression. The comparison of the lateral margin to strong

c-KIT expression identified the lateral margin as more important

for survival.

The combined multivariable model for the prediction

of DFS consisted of a) lymphadenectomy, b) absence of any of the

pathological high-risk characteristics, c) strong c-KIT expression,

and d) Breslow’s depth, and was highly statistically significant

(p=0.0004).

Discussion

Whilst in recent years great achievements in disease

awareness, in early diagnosis, and in the treatment of cutaneous

melanomas with subsequent benefits in morbidity and mortality have

been made, no similar development exists for vulvar melanomas.

Patients with vulvar melanomas usually present with the disease at

a late stage and have a poor prognosis. Its aetiology is poorly

understood and the prognostic predictors reported in the literature

are not fully conclusive. Research into vulvar melanoma is also

limited due to the low incidence of cases per centre and low

numbers of international collaborative studies or

meta-analyses.

Our comprehensive literature review of 46 studies

published from 1990 until 2012 identified Breslow’s depth and the

inguinal lymph node status as unequivocal and tumour ulceration,

age at diagnosis, and DNA ploidy as less clear or ambiguous

clinical predictors of outcome. On the molecular/genetic level,

mutations in p53, c-KIT and kinases of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR-

and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK-pathways have been reported in association with

vulvar melanoma. p53 is a tumour suppressor gene (65), c-KIT is a receptor tyrosine

kinase, mutations of which are integral for tumour growth and

progression (66), and

PI3K/AKT/mTOR- and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK-pathways regulate growth and

proliferation (67,68). By contrast, neither mutations in

BRAF or NRAS nor an involvement of viral infection

were found. These data may not be conclusive and high-throughput

transcription profiling experiments on vulvar melanomas are likely

to identify additional genes, the mutations of which are associated

with vulvar melanoma.

In our cohort of 33 adult patients, 3 cases (9.1%)

of vulvar melanoma with LS (Table

III) were identified, suggesting an association. This is

noteworthy, as to date, reported cases of LS associated with vulvar

melanomas were mainly limited to juvenile cases (16–20) (Table III). In our 3 cases, the LS was

present in melanoma in situ, but disappeared in the invasive

melanoma, where dermal hyalinisation was replaced by desmoplasia.

The limited number of reports on the association of LS with adult

vulvar melanoma may be due to under-reporting and lack of

recognition.

In our cohort, we also found an increased c-KIT

protein expression in approximately half of the patients,

suggesting a role of c-KIT in vulvar melanoma. In fact, c-KIT

mutations have been shown to be more common in vulvar than

cutaneous melanomas (13,14). c-KIT is a receptor tyrosine kinase

regulating a variety of biological responses, such as chemotaxis,

cell proliferation, apoptosis and adhesion in many cell types,

including melanocytes, and activating KIT mutations are integral

for tumour growth and progression (69); however, their role in vulvar

melanoma is yet not known.

Over the years, a number of histopatological

features have been shown to correlate with adverse prognosis. These

include Breslow’s depth, ulceration, epithelioid cell type,

microsatellitosis, regression, angiolymphatic involvement, high

mitotic rate, amelanosis and association with an existing nevus

(3,5,35,51). An American study demonstrated that

increasing Breslow depth was associated with declining survival,

whereas other histopathological features, such as ulceration,

increasing mitotic index, and the presence of atypical melanocytic

hyperplasia were not associated with a significant difference in

survival (30). A recent Chinese

study revealed that macroscopic tumour growth and treatment method

were independent prognostic factors for overall survival (70). Our study confirmed Breslow’s depth

and lymphadenectomy as strong predictors for recurrence and poorer

DFS.

Our study also identified other predictive features.

Among those was the absence of any of the pathological high-risk

characteristics (satellitosis, in-transit metastases, LVSI or

dermal mitosis) identified in a subset of patients with vulvar

melanoma. These patients survived disease with a prediction of 100%

sensitivity, making the absence of these characteristics strong

predictors for outcome, both in terms of relapse and survival. This

group of patients may qualify for follow-up after surgery,

particularly when an optimal adjuvant therapy is not available. An

increased c-KIT expression was also identified as a strong negative

predictor of DFS and a strong positive predictor of earlier

relapse. By contrast, no significant results for positivity of

lymph nodes were observed in our study, possibly due to the low

numbers of positive lymph nodes.

The identification of mutated genes, such as

c-KIT and p53 or increased levels of c-KIT in vulvar

melanomas seems consistent with the current consensus that vulvar

melanomas arise de novo from the malignant transformation of

a single junctional melanocyte in situ (4). Indeed, we found single large

junctional melanocytes adjacent to melanoma in situ, which

has, to our knowledge, not been reported previously. Mucosal

melanomas arise from an epithelium normally devoid of melanocytes;

the significance of melanocytes in a location where they are not

normally present therefore requires further investigation.

The treatment of vulvar melanomas has thus far been

largely restricted to surgical options, with little prospective

data and no randomised studies available. Following on the trend

from cutaneous melanomas, the surgical approach for vulvar

melanomas has changed from extensive to more limited procedures due

to the recognition that no improvement in overall survival can be

achieved with aggressive surgery despite increasing patient

morbidity (32,71), and no benefit is found from pelvic

lymphadenectomies in the absence of groin node metastases (72,73), similar to squamous cell carcinomas

of the vulva. In the absence of adequate randomized controlled

trials, adjuvant treatments included radiotherapy, chemotherapy,

immunotherapy, and in one case targeted therapy. Immunotherapy

using interferon α2b has shown significantly improved DFS in

randomized controlled trials, but there is significant morbidity

(74–76). The role of adjuvant radiotherapy

is unknown and may only be used in the case of close surgical

margins, whilst recurrent cancer in the absence of metastatic

disease is best managed surgically.

An important development is the evidence that

mucosal (vulvar melanomas are classified as mucosal) and cutaneous

melanomas are distinct genetic entities and should be studied and

treated as such (13,15,77). Gene mutations for cutaneous

melanomas did not prove to be of relevance in vulvar melanomas

(BRAF, NRAS) whilst p53 and c-KIT mutations were identified and may

enable therapeutic options in the future. Pathological classifiers,

such as satellitosis, in-transit metastases, LVSI and dermal

mitosis can stratify patients who would profit from the

investigation into c-KIT expression and the subsequent imatinib

treatment. Imatinib is a targeted oral therapeutic agent against

cutaneous melanomas. An Australian study has shown some efficacy

with the treatment of imatinib in mucosal melanomas, including

vulvar melanomas (78). More

studies into the genetic background, making use of high-throughput

transcription profiling technology increasingly becoming available,

are required to develop targeted treatment options, particularly in

high-risk groups.

International trials with imatinib or any other

therapeutic option available in the future in high-risk vulvar

melanomas will be beneficial, but will face all the difficulties

associated with targeting very rare tumours. The centralization of

care for patients with vulvar melanoma is inevitable. Whilst the

surgical part of their treatment is best performed in a

gynaecological cancer centre, ongoing care should best be shared

within a multi-disciplinary approach, involving both gynaecological

oncologists and melanoma centres.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Cancer Institute NSW

(09/CRF/2–02 to V.H.S.); RANZCOG (to V.H-.S.); William Maxwell

Trust (to V.H-.S.) and the Royal Hospital for Women Foundation (to

V.H-.S.).

References

|

1

|

Woolcott RJ, Henry RJ and Houghton CR:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva. Australian experience. J Reprod

Med. 33:699–702. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ragnarsson-Olding BK: Primary malignant

melanoma of the vulva - an aggressive tumor for modeling the

genesis of non-UV light-associated melanomas. Acta Oncol.

43:421–435. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bradgate MG, Rollason TP, McConkey CC, et

al: Malignant melanoma of the vulva: a clinicopathological study of

50 women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 97:124–133. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Blessing K, Kernohan NM and Park KG:

Subungual malignant melanoma: clinicopathological features of 100

cases. Histopathology. 19:425–429. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Kanter-Lewensohn LR,

Lagerlof B, et al: Malignant melanoma of the vulva in a nationwide,

25-year study of 219 Swedish females: clinical observations and

histopathologic features. Cancer. 86:1273–1284. 1999.

|

|

6

|

Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Nilsson BR,

Kanter-Lewensohn LR, et al: Malignant melanoma of the vulva in a

nationwide, 25-year study of 219 Swedish females: predictors of

survival. Cancer. 86:1285–1293. 1999.

|

|

7

|

Ragnarsson-Olding B, Platz A, Olding L, et

al: p53 protein expression and TP53 mutations in malignant

melanomas of sun-sheltered mucosal membranes versus chronically

sun-exposed skin. Melanoma Res. 14:395–401. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Irvin WP Jr, Legallo RL, Stoler MH, et al:

Vulvar melanoma: a retrospective analysis and literature review.

Gynecol Oncol. 83:457–465. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Verschraegen CF, Benjapibal M,

Supakarapongkul W, et al: Vulvar melanoma at the M.D. Anderson

Cancer Center: 25 years later. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 11:359–364.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sugiama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al:

Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet

Gynecol. 110:296–301. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hu DN, Yu GP and McCormick SA:

Population-based incidence of vulvar and vaginal melanoma in

various races and ethnic groups with comparisons to other

site-specific melanomas. Melanoma Res. 20:153–158. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mert I, Semaan A, Winer I, et al:

Vulvar/Vaginal melanoma: an updated surveillance epidemiology and

end results database review, comparison with cutaneous melanoma and

significance of racial disparities. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

23:1118–1125. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Omholt K, Grafstrom E, Kanter-Lewensohn L,

et al: KIT pathway alterations in mucosal melanomas of the vulva

and other sites. Clin Cancer Res. 17:3933–3942. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Schoenewolf NL, Bull C, Belloni B, et al:

Sinonasal, genital and acrolentiginous melanomas show distinct

characteristics of KIT expression and mutations. Eur J Cancer.

48:1842–1852. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jiveskog S, Ragnarsson-Olding B, Platz A,

et al: N-ras mutations are common in melanomas from sun-exposed

skin of humans but rare in mucosal membranes or unexposed skin. J

Invest Dermatol. 111:757–761. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Friedman RJ, Kopf AW and Jones WB:

Malignant melanoma in association with lichen sclerosus on the

vulva of a 14-year-old. Am J Dermatopathol. 6(Suppl): 253–256.

1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Egan CA, Bradley RR, Logsdon VK, et al:

Vulvar melanoma in childhood. Arch Dermatol. 133:345–348. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Carlson JA, Mu XC, Slominski A, et al:

Melanocytic proliferations associated with lichen sclerosus. Arch

Dermatol. 138:77–87. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hassanein AM, Mrstik ME, Hardt NS, et al:

Malignant melanoma associated with lichen sclerosus in the vulva of

a 10-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 21:473–476. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rosamilia LL, Schwartz JL, Lowe L, et al:

Vulvar melanoma in a 10-year-old girl in association with lichen

sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 54:S52–S53. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Powell JJ and Wojnarowska F: Lichen

sclerosus. Lancet. 353:1777–1783. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Scurry J: Does lichen sclerosus play a

central role in the pathogenesis of human papillomavirus negative

vulvar squamous cell carcinoma? The itch-scratch-lichen sclerosus

hypothesis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 9:89–97. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Smith YR and Haefner HK: Vulvar lichen

sclerosus: pathophysiology and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol.

5:105–125. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi

H, et al: Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed

lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol.

50:690–694. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Breslow A: Thickness, cross-sectional

areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma.

Ann Surg. 172:902–908. 1970. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chung AF, Woodruff JM and Lewis JL Jr:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva: a report of 44 cases. Obstet

Gynecol. 45:638–646. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Podratz KC, Gaffey TA, Symmonds RE, et al:

Melanoma of the vulva: an update. Gynecol Oncol. 16:153–168. 1983.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kim CJ, Reintgen DS and Balch CM: The new

melanoma staging system. Cancer Control. 9:9–15. 2002.

|

|

29

|

Zambo K, Szabo Z, Schmidt E, et al: Is the

clinical staging system a good choice in the staging of vulvar

malignancies? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 34:1878–1879. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tcheung WJ, Selim MA, Herndon JE 2nd, et

al: Clinicopathologic study of 85 cases of melanoma of the female

genitalia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 67:598–605. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Scheistroen M, Trope C, Koern J, et al:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva. Evaluation of prognostic factors

with emphasis on DNA ploidy in 75 patients. Cancer. 75:72–80. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Trimble EL, Lewis JL Jr, Williams LL, et

al: Management of vulvar melanoma. Gynecol Oncol. 45:254–258. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Tasseron EW, van der Esch EP, Hart AA, et

al: A clinicopathological study of 30 melanomas of the vulva.

Gynecol Oncol. 46:170–175. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Piura B, Egan M, Lopes A, et al: Malignant

melanoma of the vulva: a clinicopathologic study of 18 cases. J

Surg Oncol. 50:234–240. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ragnarsson-Olding B, Johansson H, Rutqvist

LE, et al: Malignant melanoma of the vulva and vagina. Trends in

incidence, age distribution, and long-term survival among 245

consecutive cases in Sweden 1960–1984. Cancer. 71:1893–1897.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Look KY, Reisinger M, Stehman FB, et al:

Blood transfusion and the risk of recurrence in squamous carcinoma

of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 168:1718–1723. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Phillips GL, Bundy BN, Okagaki T, et al:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva treated by radical hemivulvectomy.

A prospective study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer.

73:2626–2632. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dunton CJ, Kautzky M and Hanau C:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv.

50:739–746. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Raber G, Mempel V, Jackisch C, et al:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva. Report of 89 patients. Cancer.

78:2353–2358. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Trimble EL: Melanomas of the vulva and

vagina. Oncology (Williston Park). 10:1017–1024. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Scheistroen M, Trope C, Kaern J, et al:

Malignant melanoma of the vulva FIGO stage I: evaluation of

prognostic factors in 43 patients with emphasis on DNA ploidy and

surgical treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 61:253–258. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Strauss BS: Silent and multiple mutations

in p53 and the question of the hypermutability of tumors.

Carcinogenesis. 18:1445–1452. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

De Matos P, Tyler D and Seigler HF:

Mucosal melanoma of the female genitalia: a clinicopathologic study

of forty-three cases at Duke University Medical Center. Surgery.

124:38–48. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Larsson KB, Shaw HM, Thompson JF, et al:

Primary mucosal and glans penis melanomas: the Sydney Melanoma Unit

experience. Aust N Z J Surg. 69:121–126. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Creasman WT, Phillips JL and Menck HR: A

survey of hospital management practices for vulvar melanoma. J Am

Coll Surg. 188:670–675. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Raspagliesi F, Ditto A, Paladini D, et al:

Prognostic indicators in melanoma of the vulva. Ann Surg Oncol.

7:738–742. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Karsberg S, Platz A,

et al: Mutations in the TP53 gene in human malignant melanomas

derived from sun-exposed skin and unexposed mucosal membranes.

Melanoma Res. 12:453–463. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

De Hullu JA, Hollema H, Hoekstra HJ, et

al: Vulvar melanoma: is there a role for sentinel lymph node

biopsy? Cancer. 94:486–491. 2002.

|

|

49

|

Finan MA and Barre G: Bartholin’s gland

carcinoma, malignant melanoma and other rare tumours of the vulva.

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 17:609–633. 2003.

|

|

50

|

Harting MS and Kim KB: Biochemotherapy in

patients with advanced vulvovaginal mucosal melanoma. Melanoma Res.

14:517–520. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wechter ME, Gruber SB, Haefner HK, et al:

Vulvar melanoma: a report of 20 cases and review of the literature.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 50:554–562. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Edwards RH, Ward MR, Wu H, et al: Absence

of BRAF mutations in UV-protected mucosal melanomas. J Med Genet.

41:270–272. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Dahlgren L, Schedvins K, Kanter-Lewensohn

L, et al: Human papilloma virus (HPV) is rarely detected in

malignant melanomas of sun sheltered mucosal membranes. Acta Oncol.

44:694–699. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Stang A, Streller B, Eisinger B, et al:

Population-based incidence rates of malignant melanoma of the vulva

in Germany. Gynecol Oncol. 96:216–221. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Rouzier R, Haddad B, Atallah D, et al:

Surgery for vulvar cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 48:869–878. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lundberg R, Brytting M, Dahlgren L, et al:

Human herpes virus DNA is rarely detected in non-UV

light-associated primary malignant melanomas of mucous membranes.

Anticancer Res. 26:3627–3631. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Dhar KK, Das N, Brinkman DA, et al:

Utility of sentinel node biopsy in vulvar and vaginal melanoma:

report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 17:720–723. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Giraud G, Ramqvist T, Ragnarsson-Olding B,

et al: DNA from BK virus and JC virus and from KI, WU, and MC

polyomaviruses as well as from simian virus 40 is not detected in

non-UV-light-associated primary malignant melanomas of mucous

membranes. J Clin Microbiol. 46:3595–3598. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al:

Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature.

Melanoma Res. 18:127–133. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Moan J, Porojnicu AC, Dahlback A, et al:

Where the sun does not shine: is sunshine protective against

melanoma of the vulva? J Photochem Photobiol B. 101:179–183. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Trifiro G, Travaini LL, Sanvito F, et al:

Sentinel node detection by lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph

node biopsy in vulvar melanoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging.

37:736–741. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Terlou A, Blok LJ, Helmerhorst TJ, et al:

Premalignant epithelial disorders of the vulva: squamous vulvar

intraepithelial neoplasia, vulvar Paget’s disease and melanoma in

situ. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 89:741–748. 2010.

|

|

63

|

Baiocchi G, Duprat JP, Neves RI, et al:

Vulvar melanoma: report on eleven cases and review of the

literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 128:38–41. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ragnarsson-Olding BK: Spatial density of

primary malignant melanoma in sun-shielded body sites: a potential

guide to melanoma genesis. Acta Oncol. 50:323–328. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Muller PA and Vousden KH: p53 mutations in

cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 15:2–8. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Postow MA and Carvajal RD: Therapeutic

implications of KIT in melanoma. Cancer J. 18:137–141. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Markman B, Dienstmann R and Tabernero J:

Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway-beyond rapalogs. Oncotarget.

1:530–543. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

De Luca A, Maiello MR, D’Alessio A, et al:

The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathways: role in

cancer pathogenesis and implications for therapeutic approaches.

Expert Opin Ther Targets. 16(Suppl 2): S17–S27. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Mehnert JM and Kluger HM: Driver mutations

in melanoma: lessons learned from bench-to-bedside studies. Curr

Oncol Rep. 14:449–457. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Huang Q, Huang H, Wan T, Deng T and Liu J:

Clinical outcome of 31 patients with primary malignant melanoma of

the vagina. J Gynecol Oncol. 24:330–335. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Kornberg R, Harris M and Ackerman AB:

Epidermotropically metastatic malignant melanoma. Differentiating

malignant melanoma metastatic to the epidermis from malignant

melanoma primary in the epidermis. Arch Dermatol. 114:67–69. 1978.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Jaramillo BA, Ganjei P, Averette HE, et

al: Malignant melanoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 66:398–401.

1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Beller U, Demopoulos RI and Beckman EM:

Vulvovaginal melanoma. A clinicopathologic study. J Reprod Med.

31:315–319. 1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS,

et al: Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected

cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial

EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 14:7–17. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim J, Lawson DH, et al:

High-dose interferon alfa-2b does not diminish antibody response to

GM2 vaccination in patients with resected melanoma: results of the

Multicenter Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase II Trial

E2696. J Clin Oncol. 19:1430–1436. 2001.

|

|

76

|

Gray RJ, Pockaj BA and Kirkwood JM: An

update on adjuvant interferon for melanoma. Cancer Control.

9:16–21. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Dunton CJ and Berd D: Vulvar melanoma,

biologically different from other cutaneous melanomas. Lancet.

354:2013–2014. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Handolias D, Salemi R, Murray W, et al:

Mutations in KIT occur at low frequency in melanomas arising from

anatomical sites associated with chronic and intermittent sun

exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 23:210–215. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|