Introduction

Bisphosphonates (BPs) are analogues of pyrophosphate

that are known to prevent bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclast

activity (reviewed in ref. 1).

BPs are used for the treatment of various bone diseases, including

osteoporosis and bone metastasis in cancer with or without

hypercalcemia (2).

Nitrogen-containing BPs, such as zoledronic acid (ZA), are used in

the treatment of osteoporosis and bone metastasis (reviewed in ref.

3), as well as in the treatment

of other bone diseases, such as Erdheim-Chester disease (4). In addition, they are more potent

inhibitors of bone resorption than non-nitrogen-containing BPs

(reviewed in ref. 5). However,

despite their several benefits, ZA induces BP-related osteonecrosis

of the jaw (BRONJ) in cancer patients (6,7).

BRONJ is defined as necrotic bone exposure in the oral cavity

continuing for >8 weeks in BP-treated patients who have not had

received head and neck radiation therapy (8). The molecular mechanisms responsible

for the development of BRONJ remain to be elucidated; however, some

risk factors, including periodontitis with bacterial plaque in the

oral cavity have been associated with this symptom (reviewed in

ref. 7). Previous studies have

suggested that infectious agents, including Actinomyces,

play important roles in the etiology and progression of BRONJ

(9–11). Interestingly, Kobayashi et

al reported that ZA promoted the adherence of Streptococcus

mutans to hydroxyapatite and the proliferation of oral bacteria

obtained from healthy individuals, suggesting that ZA increases

bacterial infection (12). Wound

closure by oral epithelial cells (ECs) and gingival fibroblasts

(GFs) is important, not only for successful wound healing, but also

for the protection of the socket from oral bacterial infection

following tooth extraction. Thus, it is possible that an oral

bacterial infection may induce BRONJ in cooperation with other risk

factors, such as diabetes mellitus with steroid intake (13) or with microvascular disease

(14), smoking, prosthetic

trauma, and implant treatment (15). In addition, the ability of GFs to

migrate and synthesize type I collagen is essential for the

formation of rigid gingival connective tissue to cover the

intraoral bone exposure, which protects the alveolar bone of the

maxilla and the jaw from infection with oral bacteria. However, the

mechanisms through which ZA affects the ability of human GFs (hGFs)

to migrate and synthesize the connective tissue at the molecular

level remain to be elucidated.

When tissue injury occurs, the blood coagulation

cascade is initiated, resulting in the formation of fibrous

connective tissue, which functions as a scaffold for the influx of

inflammatory cells. Platelets also aggregate at the site of injury,

and become activated by binding to the negatively charged

extravascular fibrous tissue, and release various growth factors,

including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (reviewed in ref.

16). TGF-β1 is known to be

expressed in serveral types of cells, including hGFs, and is

involved in the proliferation and differentiation of these cells

(17,18). Thus, the functions of TGF-β seem

to be autocrine or paracrine as regards the regulation of hGFs

during oral inflammation and the wound healing processes at the

site of injury. The TGF-β superfamily consists of two families: the

TGF-β/activin/Nodal family and the bone morphogenetic protein

(BMP)/growth and differentiation factor (GDF)/Mullerian inhibiting

substance (MIS) family (reviewed in ref. 19).

The TGF-β superfamily ligands initiate a cascade of

signaling events by binding to their respective type I and type II

receptors in the extracellular space. Following this, two type I

and two type II receptors form a tetrameric complex. In this

ligand-bound complex of type I and type II receptors, the type II

receptor kinase activates the type I receptor kinase. The type I

receptor induces intracellular signal transduction by

phosphorylating the receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads) (reviewed in

refs. 20–23). Smads are central signal

transducers of TGF-β superfamily and are composed of 3 groups. The

first group comprises the R-Smads; Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 are

primarily activated by the BMP-specific type I receptors, whereas

Smad2 and Smad3 are activated by TGF-β-specific type I receptors.

The second group contains the common mediator Smad (Co-Smad; e.g.,

Smad4). The third group comprises the inhibitory Smads (I-Smads;

e.g., Smad6 and Smad7). Activated R-Smads form complexes with the

Co-Smad, which enter the nucleus, and, together with other

cooperative proteins, positively or negatively control the

transcription of specific target genes. I-Smads suppress the

activation of R-Smads by competing with R-Smads for type I receptor

interaction and by recruiting specific ubiquitin ligases, resulting

in their proteasomal degradation (reviewed in ref. 24).

TGF-β has the ability to induce the differentiation

of various types of cells into myofibroblasts (MFs), which

typically exhibit the formation of F-actin stress fibers (reviewed

in ref. 25). We have previously

demonstrated that TGF-β induces the expression of the MF markers,

α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and type I collagen, in fibroblastic

cells derived from periodontal ligament (26). Sobral et al reported that

TGF-β induced the differentiation of hGFs into MFs in a

Smad-dependent manner (27).

Thus, TGF-β is now known to induce MF differentiation from

fibroblasts, which preferentially form a fibrous tissue. TGF-β is

also known to induce migratory activity in various types of cells,

including fibroblastic cells in a Smad-dependent manner (28–30). In addition, Bakin et al

reported that TGF-β regulates the migratory activity of ECs in a

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent manner

(31), suggesting that TGF-β

induces cell migratory activity through MAPKs as opposed to Smads.

Moreover, TGF-β plays important roles in physiological wound

closure by promoting cell migration and type I collagen synthesis.

On the other hand, the abnormal and persistent appearance of MFs

causes scar formation or fibrosis (32,33). The abnormal potentiation of TGF-β

signaling in MFs possibly causes fibrogenic diseases. Therefore,

MFs represent key players in the physiological reconstruction of

connective tissue following injury and in generating the

pathological tissue deformations that characterize fibrosis

(34).

In this study, we investigated the mechanisms

through which ZA, at its maximum concentration in serum (Cmax),

which clinically, is usually found after the intravenous

administration of 4 mg ZA, which is the appropriate amount for the

usual treatment of bone metastasis (35,36) or bone diseases such as

Erdheim-Chester disease (4),

affects TGF-β-induced intracellular signal transduction and MF

differentiation of hGFs, which are important processes for the

progression of fibrogenesis during inflammation.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Recombinant TGF-β was purchased from Peprotech, Inc.

(Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). The TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor,

SB-431542, which preferentially suppresses the activation of the

intracellular signal transduction of Smad2 by this receptor

(37,38), and sometimes broadly suppresses

the TGF-β1-induced activation of p38 MAPK, and extracellular

signal-regulated kinase (ERK) as opposed to Smad2 (30) was purchased from Calbiochem (La

Jolla, CA, USA). Zometa® obtained from Novartis

Pharmaceuticals (Tokyo, Japan) was used as ZA in all our

experiments. The Cmax of ZA in an adult human body is approximately

1.47 µM within 15 min after its intravenous administration

(4 mg/5 ml) according to the user instructions provided with

Zometa®. This is the appropriate amount of ZA for the

treatment of cancer bone metastasis (32,33), and is referred in the internal

document ZOMU00007 belonging to Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Cell culture

hGFs were isolated and cultured as described in our

previous study (39). Briefly,

the cells were isolated from the fresh gingival tissue biopsy

samples of 3 volunteers, and were maintained in a Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin (both from Invitrogen,

Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Informed consent was obtained from all the

volunteers prior to obtaining the samples, and the Ethics Committee

of Iwate Medical University approved the research protocol

(approval no. 1126). Subsequently, one hGF culture retaining a high

proliferative potential among the 3 cultures was used. NIH3T3 mouse

embryonic fibroblasts (used as a standard control for the

fibroblasts), obtained from RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan), were

cultured with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and

penicillin-streptomycin (both from Invitrogen).

Cell viability assay

The status of cell viability was evaluated using an

alamarBlue assay (AbD Serotec, Oxon, UK) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. This assay reagent includes an

indicator that fluoresces and undergoes colorimetric changes when

reduced by mitochondrial respiration, which is proportional to the

number of living cells. For the viability assay, the cells were

seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2.48×103

cells/well and cultured for 48 h in medium containing 10% FBS, with

or without ZA at the indicated concentrations (0.0147-147

µM). Some of the cells were subsequently treated with TGF-β1

(1–5 ng/ml) for 24 h following treatment with ZA. The medium was

replaced with DMEM containing 10% alamarBlue solution to evaluate

the viability of the cells, and the cells were cultured for an

additional 4.5 h. The absorbance in each well was measured using an

ELISA plate reader (Tosoh Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The data were

presented as values of Abs570 − Abs600. Each

experiment was repeated 3 times, with 5-wells dedicated for each

time point.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA from the hGFs and NIH3T3 cells was

isolated using ISOGEN II reagent (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was

synthesized from total RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit

(Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). PCR was subsequently performed on a

Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time system using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II

(both from Takara Bio) with specific oligonucleotide primers (human

α-SMA forward, 5′-ATACAACATGGCATCATCACCAA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGGCAACACGAAGCTCATTGTA-3′; mouse α-SMA forward,

5′-CAGATGTGGATACAGCAAACAGGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GACTTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGA-3′; human TGF-β type I receptor forward,

5′-GCTGCTCCTCCTCGTGCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGTCTTTTGTACAGAGGTGGC-3′;

human TGF-β type II receptor forward, 5′-CTGCACATCGTCCTGTGG-3′ and

reverse, 5′-GGAAACTTGACTGCACCGTT-3′; and human glyceraldehyde

3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward,

5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-ATGGTGGTGAAGACCCCACT-3′;

and mouse GAPDH forward, 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG-3′). The mRNA expression levels of α-SMA,

TGF-β type I receptor and TGF-β type II receptor were normalized to

those of GAPDH, and the relative expression levels were presented

as the fold increase or decrease relative to the control.

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl

(pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1%

SDS] or lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA

and 1% Triton® X-100] containing protease and

phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (both from Sigma, St. Louis, MO,

USA). The protein content of the samples was measured using BCA

reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples containing equal

amounts of protein were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels

and transferred onto a polyvinylidenedifluoride membrane (Millipore

Corp., Bedford, MA, USA). After being blocked with 1% BSA or 1%

skim milk in T-TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl and 0.05%

Tween-20), the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies

including anti-α-SMA rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1,000; ab5694;

Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-Smad2/3 purified mouse monoclonal

antibody (1:1,000; 610842; BD Transduction Laboratories™, Franklin

Lakes, NJ, USA), anti-phospho-Smad2/3 (#8828), anti-p38 MAPK

(#9212), anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (#9211), anti-c-Jun N-terminal

kinase (JNK; #9251) and anti-phospho-JNK polyclonal antibodies

(#9252) (1:1,000; all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.,

Beverly, MA, USA) and anti-α-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody

(1:25,000; #3873, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) as a loading

control for normalization. The proteins of interest were then

detected using appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and an

Amersham ECL™ Prime Western Blotting Detection reagent (GE

Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Immunofluorescence analysis of cultured

cells

For immunofluorescence analysis of the cultured

cells, the hGFs were subcultured on non-coated cover glass slips

(Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd. Kishiwada, Japan) at a density of

2.5×104 cells/glass slip (BD Biosciences, Franklin

Lakes, NJ, USA) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS,

with or without ZA (1.47 µM) for 48 h. The culture medium

was replaced with DMEM without FBS, supplemented with or without

TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml). The cells were maintained in this medium for 4 or

5 days, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto,

Japan) for 15 min and permeabilized with Triton X-100 (Sigma).

Following background reduction with normal goat serum, the cells

were labeled with anti-α-SMA rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100;

ab5694; Abcam), or anti-collagen type I rabbit polyclonal antibody

(1:100; 600-401-103-0.1; Rockland, Inc., Rockland, ME, USA) at room

temperature for 1 h. After being washed with phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS) to remove the excess primary antibody, the cells were

incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000; A-11034; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The

Netherlands) and DAPI (1:1,000; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) for 30

min at room temperature. After being washed with PBS to remove the

excess secondary antibody, the fluorescent signal was detected

using an Olympus IX70 fluorescence microscope with the LCPIanFI 20

objective lens (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Evaluation of the migratory activities of

hGFs and NIH3T3 cells

Cell migration assays were performed using

Transwell® membrane cell culture inserts (8 µm

pore size; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The hGFs were cultured with or without

ZA (1.47 µM) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 48 h at a

cell density of 6.0×105 cells in 10 cm culture dish. The

cells were then placed at a density of 1.0×105 cells in

the cell culture inserts in the each well of a 24-well cell culture

plate in DMEM with 0.1% BSA. The cells were allowed to migrate

through the porous membrane that bordered the upper cell culture

insert and the lower well of 24-well culture plate which contained

DMEM in the presence or absence of TGF-β (5 ng/ml) for 6 h at 37°C.

TGF-β was added to the culture medium in the lower well of 24-well

culture plate. In some cases, SB-431542 was added to both the upper

and lower culture media. The cells on the upper side of the

membrane were wiped, and the membrane was fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde in PBS. After being washed with PBS, the cells

that had migrated onto the underside of the membrane were labeled

with DAPI (1:1,000; KPL) and counted. The values were shown as

average of those from 3 wells. The evaluation of the migratory

activity of the NIH3T3 cells was performed as described above

without pre-treatment of the cells with ZA.

Flow cytometry

The hGFs were cultured with or without ZA (1.47

µM) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 48 h at a density

of 6.0×105 cells in a 10-cm culture dish. The cells

(1.0×105 cells) were suspended in PBS containing 0.5%

FBS and 2 mM EDTA and incubated with anti-TGF-β receptor type I

(1:100; ab30103) or type II (1:50; ab78419) (both from Abcam)

primary antibodies for 1 h at 4°C. For the negative control

experiments, the cells were incubated with the same protein amount

of normal control IgG (sc-2028; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.,

Santa Cruz, CA, USA) as each specific antibody. The cells were then

incubated with PE-conjugated secondary antibodies (#732988 for

ab31013; #732970 for ab78419) for 30 min in the dark. Acquisition

was performed using an EPICS XL EXPO 32 ADC system (Beckman

Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3 or 5

experiments). The data were statistically analyzed using the

Student's t-test, and P<0.01 (indicated by an asterisk) was

considered significant. The results shown in all experiments are

representative of at least 3 separate experiments.

Results

ZA suppresses the TGFβ1-induced increase

in the viability of hGFs

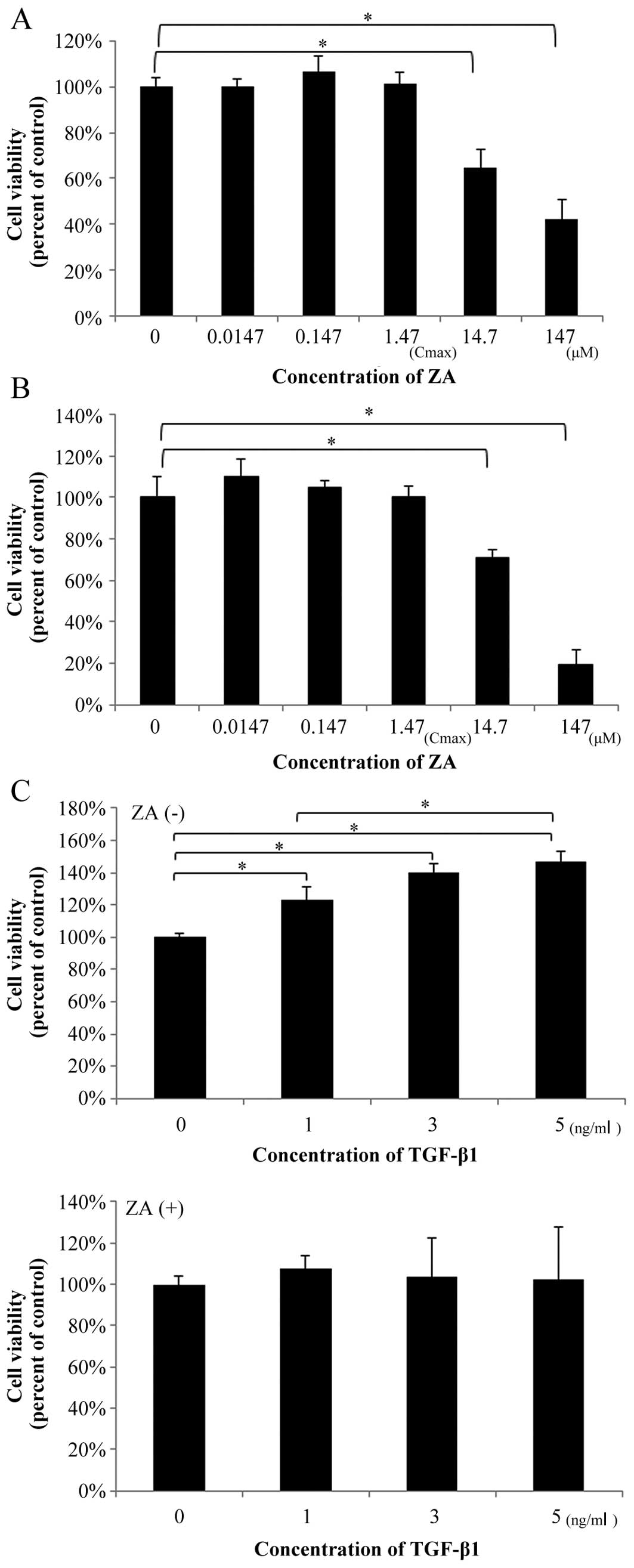

Treatment with ZA for 48 h in medium containing 10%

FBS at the concentrations of 0.0147 µM (1/100 of Cmax),

0.147 µM (1/10 of Cmax) and 1.47 µM (Cmax) did not

affect the viability of the hGFs (Fig. 1A) and the NIH3T3 cells which were

used as a standard control for the fibroblasts (Fig. 1B). However, at 10-100-fold higher

concentrations (14.7–147 µM) than the Cmax, ZA significantly

suppressed the viability of the hGFs (35–58% suppression of the

control) and that of the NIH3T3 cells (29–80% suppression of the

control) in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, ZA (Cmax) does not

affect the viability of hGFs and normal standard fibroblasts at 48

h following administration.

In order to elucidate the mechanisms through which

ZA affects TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis by hGFs, the hGFs were

pre-treated with ZA (Cmax) for 48 h and subsequently treated with

TGF-β1 at the indicated concentrations for the indicated periods of

time. Finally, the effect of pre-treatment with ZA (Cmax) on

TGF-β-induced functions in hGFs was investigated using the

following experiments:

We examined whether ZA (Cmax) affects the viability

of hGFs stimulated with TGF-β1 (1–5 ng/ml). As shown in Fig. 1C (upper graph), TGF-β1 (1–5 ng/ml)

increased the viability of the hGFs (23–47% promotion of the

control). However, ZA (Cmax) suppressed the TGFβ1-induced increase

in the viability of the hGFs (Fig.

1C, lower graph; compare same TGF-β1 concentrations between

graphs).

ZA (Cmax) suppresses the TGF-β-induced MF

differentiation of hGFs

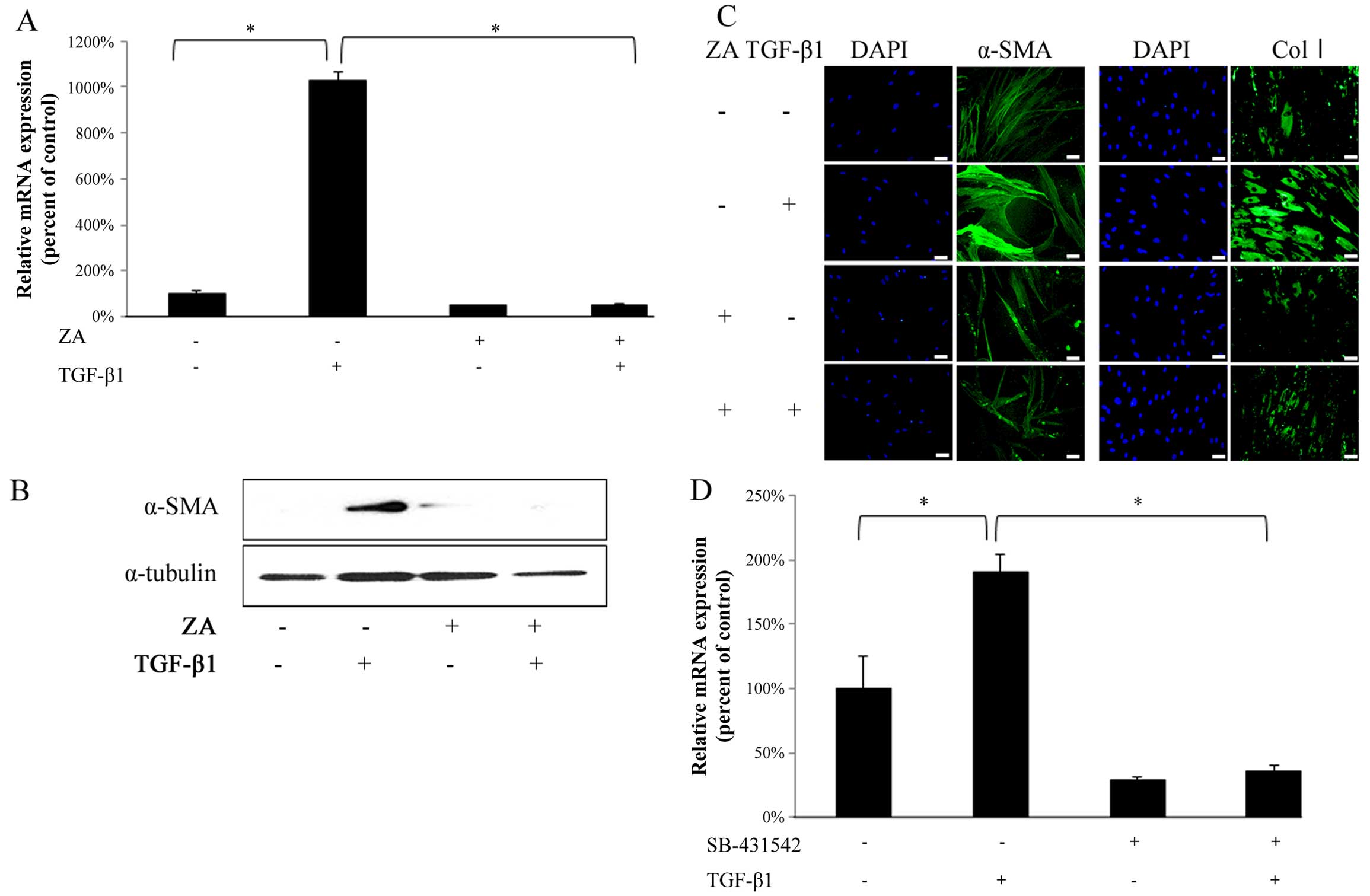

TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) significantly upregulated the α-SMA

mRNA expression level in the hGFs (Fig. 2A, bars 1 and 2 from left). ZA

(Cmax) completely suppressed the TGF-β1-induced increase in the

mRNA expression of α-SMA in the hGFs (Fig. 2A, bars 2 and 4 from left). In

addition, western blot analysis revealed that ZA (Cmax) clearly

suppressed the TGF-β1-induced upregulation of α-SMA expression at

the protein level in the hGFs (Fig.

2B). Immunofluorescence staining also revealed that ZA (Cmax)

clearly suppressed the TGF-β1-induced upregulation of α-SMA

expression (Fig. 2C, left panels)

and type I collagen expression (Fig.

2C, right panels) at the protein level in the hGFs. We

confirmed that the TGF-β1-induced increase in the mRNA expression

of α-SMA in the hGFs was significantly inhibited by SB-431542, an

inhibitor of TGF-β type I receptor (Fig. 2D), indicating that TGF-β1

specifically induced the MF differentiation of hGFs through

ligand-receptor interaction. Thus, these results indicate that ZA

(Cmax) suppresses the TGF-β-induced MF differentiation of hGFs.

ZA (Cmax) inhibits the TGF-β-induced

migratory activity of hGFs

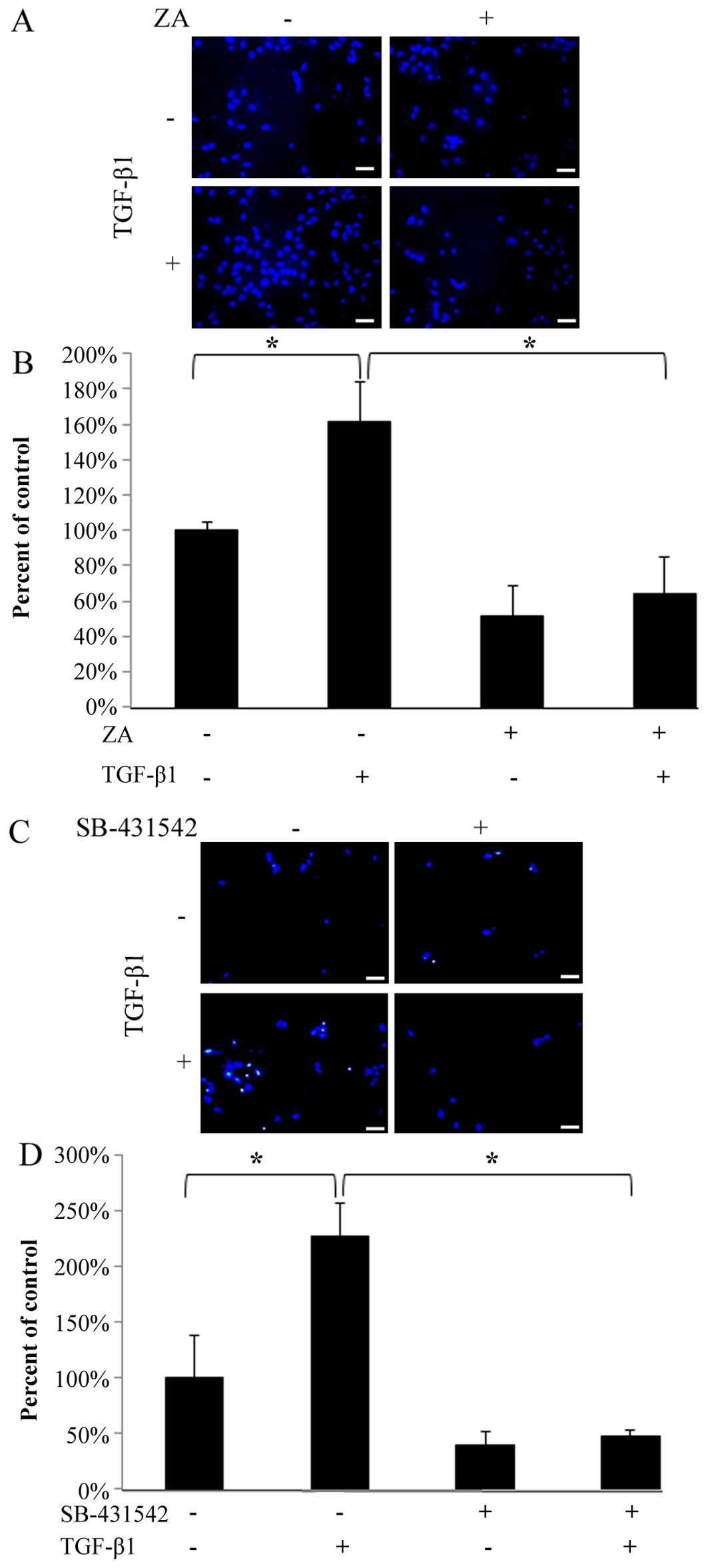

As shown in Fig. 3A

and C, the migration of the hGFs through the porous membrane

that bordered the upper and lower chambers was significantly

enhanced by stimulation with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml). However, ZA (Cmax)

completely suppressed the TGF-β1-induced migratory activity

(Fig. 3A and B). In addition, we

confirmed that the TGF-β-induced migratory activity was markedly

inhibited by SB-431542 (Fig. 3C and

D), indicating that TGF-β1 specifically induced the migration

of hGFs through ligand-receptor interaction. These results indicate

that ZA (Cmax) inhibits the TGF-β-induced migratory activity of

hGFs.

ZA (Cmax) suppresses the expression of

TGF-β type I receptor on the surfaces of hGFs and the TGF-β-induced

phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in hGFs

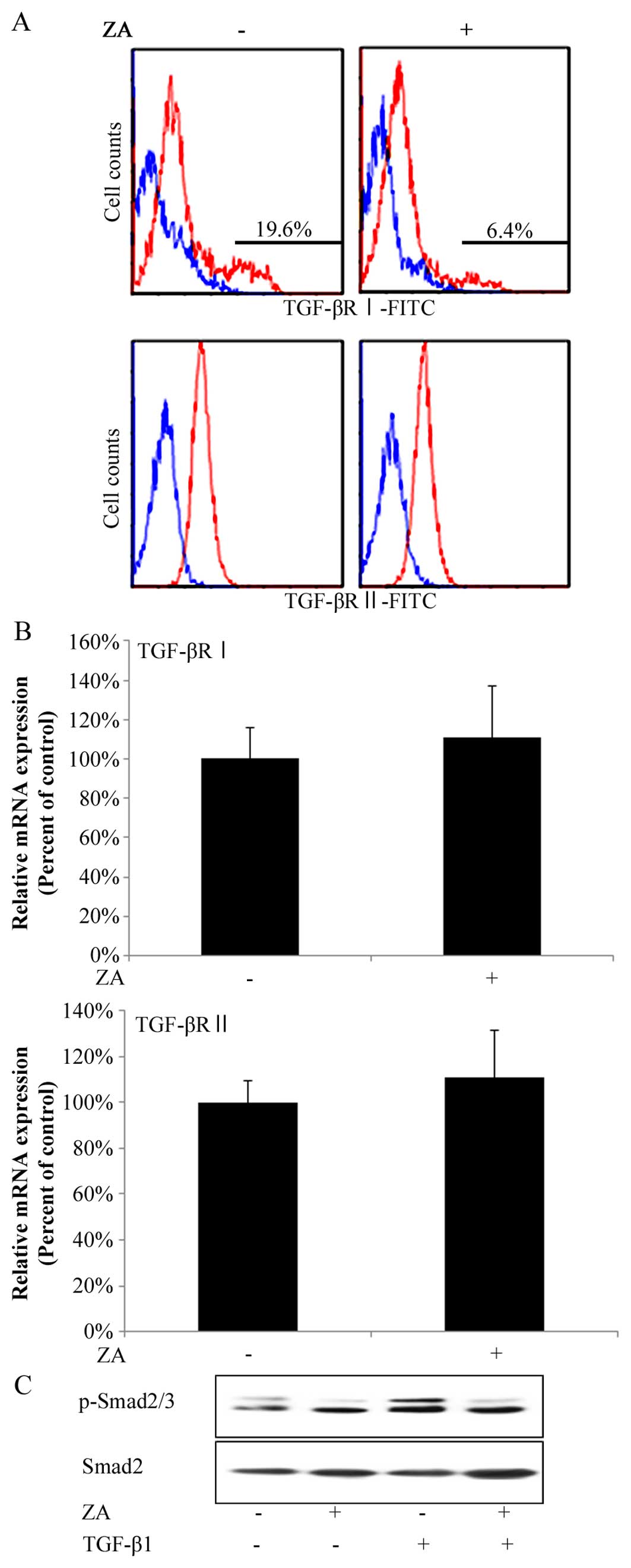

In order to gain insight into the molecular

mechanisms underlying the suppressive effects of ZA (Cmax) on

TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis by hGFs, we investigated whether ZA

affects the expression of TGF-β type I and II receptors on the

surface of hGFs. In flow cytometric analysis, hGFs had two peaks in

the histogram of TGF-β type I receptor-positive cells, that is, 2

groups of hGFs weakly or strongly expressed TGF-β type I receptors,

respectively (Fig. 4A, upper left

panel). Intriguingly, ZA (Cmax) lowered the ratio of the number of

cells strongly expressing TGF-β type I receptors on their surface

against that of total hGFs by 19.6 to 6.4% (Fig. 4A, upper panels). By contrast, hGFs

had only one peak in the histogram of TGF-β type II

receptor-positive cells (Fig. 4A,

lower left panel). ZA (Cmax) did not change the position of the

peak in the histogram of TGF-β type II receptor-positive cells

(Fig. 4A, lower panels).

Moreover, RT-qPCR analysis revealed that ZA (Cmax) did not decrease

the total amount of both TGF-β receptor type (types I and II)

expression at the mRNA level (Fig.

4B, upper and lower graphs, respectively), suggesting that ZA

(Cmax) suppressed the expression of TGF-β type I receptor on the

surface of hGFs. In addition, ZA (Cmax) suppressed the TGF-β1 (5

ng/ml)-induced phosphorylation of Smad2/3 (Fig. 4C). We confirmed these results by

reproducing them in independent experiments.

Discussion

Wang et al reported that TGF-β1 increased the

viability of human dermal fibroblasts (40). We found that ZA (Cmax) reduced the

TGF-β1-induced increase in the viability of hGFs (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that ZA

(Cmax) possibly suppresses the TGF-β1-induced fibrogenesis in oral

gingival tissue. Lu et al reported that TGF-β1 promoted the

viability of pulmonary artery endothelial cells through

Smad2-mediated signal transduction (41). We found that ZA (Cmax) suppressed

the TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml)-induced phosphorylation of Smad2/3 (Fig. 4C), implicating that ZA (Cmax) may

possibly suppress the TGF-β1-induced promotion of the viability of

hGFs through suppression of Smad2/3 activities.

Pan et al or Koch et al reported that

5 or 50 µM ZA induced the osteoblastic differentiation of

osteoblast precursor cells (42,43). In addition, Chen et al

reported that 10 µM ZA induced the dendritic cell

differentiation of monocytes (44). However, the mechanisms through

which ZA (Cmax) affected the differentiation ability of cells

derived from the oral cavity remained to be elucidated. In this

study, we demonstrated that 1.47 µM ZA (Cmax) significantly

suppressed the TGF-β1-induced MF differentiation of hGFs (Fig. 2A, B, and C). These results

strongly suggest that ZA (Cmax) inhibits wound healing in the oral

cavity by the attenuation of type I collagen synthesis in MFs

differentiated from hGFs following TGF-β1 stimulation. In addition,

it is generally known that MFs play an important role in generating

a contractile force, facilitating wound closure (reviewed in ref.

16), suggesting that ZA (Cmax)

also interferes with this process through the suppression of the

TGF-β1-induced MF differentiation of hGFs. Of note, we found that

ZA (Cmax) clearly suppressed the TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of

Smad2/3 in hGFs (Fig. 4C).

Smad2/3 are known to be key signaling molecules inducing the MF

differentiation of fibroblasts (27). These results suggest that ZA

(Cmax) suppressed TGF-β1-induced MF differentiation of hGFs through

inhibition of Smad2/3 phosphorylation by TGF-β1.

Pabst et al reported that ZA at 50 µM,

a much higher concentration than Cmax, significantly decreased the

migratory activity of human oral keratinocytes at 72 h following

treatment with ZA (45). However,

it remained to be clarified whether ZA (Cmax) affected the

migratory activity of various cells derived from the oral cavity,

including hGFs. On the other hand, TGF-β is known to induce

migratory activity in various types of cells, including

fibroblastic cells, in a Smad-dependent manner (28–30). In this study, we demonstrated that

ZA (Cmax) significantly suppressed the TGF-β1-induced migratory

activity of hGFs (Fig. 3A and B).

Wound healing or mucous re-epithelialization is a complex process

involving the proliferation and migration of mesenchymal cells,

such as fibroblasts and MFs, which construct granulation tissue for

wound closure and then induce mucous re-epithelialization on it

(reviewed in ref. 46). As

described above, ZA (Cmax) suppressed TGF-β1-induced

phosphorylation of Smad2/3 (Fig.

4C). These results suggest that ZA (Cmax) suppresses wound

closure with granulation tissue in the oral cavity by the

inhibition of the TGF-β1-induced migration of mesenchymal cells,

such as hGFs by suppressing Smad2/3 phosphorylation by TGF-β1. On

the other hand, Ozdamar et al (47) reported that the phosphorylation of

polarity protein Par6 is required for TGF-β1-dependent

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in mammary gland ECs and

controls the interaction of Par6 with the E3 ubiquitin ligase

Smurf1. Smurf1, in turn, targets the guanosine triphosphatase RhoA

for degradation, thereby leading to a loss of tight junctions

(47). In addition, RhoA is

generally known to be a regulator of cell migratory activity in

various types of cells by promoting stress fiber assembly and the

resultant cell adhesion (48).

Intriguingly, serine-to-alanine point mutation [Par6(S345A)] of the

TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation site in Par6 suppressed the

TGF-β1-induced EMT in a Smad-independent manner. It remains to be

clarified whether ZA (Cmax) suppresses the TGF-β1-induced migratory

activity of hGFs through affecting Par6/Smurf1/RohA signal

transduction pathway in a Smad-independent manner.

Saito et al demonstrated the negative effects

of ZA on the re-epithelialization of oral mucosa in a

three-dimensional in vitro oral mucosa wound healing model

(49). They demonstrated

histologically that ZA downregulated the expression of TGF-β type I

and II receptors and Smad3 phosphorylation in oral keratinocytes.

However, they used ZA at 10 µM, which was a much higher

concentration than Cmax, for evaluating the effects on

TGF-β1-induced signal transduction in human oral keratinocytes.

Moreover, they did not elucidate how TGF-β-induced intracellular

signals affect the function of human oral keratinocytes at the

cellular and molecular levels. In this study, we demonstrated that

ZA (Cmax) lowered the ratio of the number of cells strongly

expressing TGF-β type I receptors on their surface against that of

total hGFs, but did not affect the expression status of TGF-β type

II receptors on hGFs (Fig. 4A).

This finding suggests that ZA (Cmax) preferentially suppresses the

expression of TGF-β type I receptor over that of TGF-β type II

receptor on the surfaces of hGFs. By contrast, as described above,

a high concentration of ZA (10 µM) seemed to downregulate

the expression of both TGF-β receptor types (types I and II). In

addition, we found that ZA (Cmax) suppressed the TGF-β1-induced

phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in hGFs (Fig. 4C), implicating that the

suppression of the TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in

hGFs by ZA (Cmax) may be caused by the inhibition of TGF-β type I

receptor expression on the surfaces of hGFs. However, it remains to

be clarified whether ZA (Cmax) directly suppresses the

TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of Smad2/3, or indirectly suppresses

that through the inhibition of the TGF-β type I receptor expression

on the surface of hGFs. On the other hand, Okamoto et al

demonstrated that ZA (30-50 µM) induced apoptosis and

S-phase arrest in mesothelioma by inhibiting the functions of Rab

family proteins (50). The Rab

family is generally known to control the endosomal trafficking of

membrane molecules, such as growth factor receptors (reviewed in

ref. 51). It is also generally

known that Rab5, activated by a guanine nucleotide exchange factor

(GEF), directs TGF-β-activated receptors into the endocytic pathway

that promotes TGF-β-induced Smad2/3-dependent signals (52). In addition, Kardassis et al

suggested that TGF-β receptors may be recycled on the cell membrane

in a Rab-11-dependent manner following clathrin-dependent

internalization of TGF-β receptors, which may positively affect the

activities of Smad2/3-dependent TGF-β-induced intracellular signals

mediated by these receptors (53). Our laboratory is currently

investigating whether ZA (Cmax) suppresses the function of Rab

family members that may upregulate the activity of TGF-β1-induced

Smad2/3-dependent intracellular signals in hGFs at the receptor

level, thereby resulting in downregulating TGF-β1-induced

fibrogenic activity of the cells.

As described above, it has been reported that the

TGF-β-induced activation of p38 MAPK positively regulates migratory

activity (31). In fact, TGF-β1

upregulated the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in hGFs; however, ZA

(Cmax) did not suppress the TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml)-induced

phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in hGFs (data not shown), suggesting

that p38 MAPK activity is not related to the suppressive effects of

ZA (Cmax) on TGF-β1-induced fibrogenic activity of hGFs. It is

plausible that the suppression of type I receptor expression on the

surface of hGFs by ZA (Cmax), as shown in Fig. 4A, may not be sufficient to

suppress the TGF-β1-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation. On the other

hand, the activation of MAPKs such as JNK and p38 MAPK, but not

ERK, is necessary for the progression of the hypoxia-induced MF

differentiation of fibroblasts (54). Although, in western blot analysis,

the phosphorylation of JNK was not detectable in hGFs before/after

TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) stimulation (data not shown), it remains to be

clarified whether JNK affects the TGF-β1-induced fibrogenic and

migratory activities of hGFs. In addition, the mechanisms through

which p38 MAPK affects the TGF-β1-induced fibrogenic and migratory

activities of hGFs also remains to be clarified.

In conclusion, in the present study, it was

suggested that ZA (Cmax) attenuates TGF-β1-induced wound closure by

inhibiting the formation of granulation tissue by hGFs stimulated

with TGF-β1 that was derived from inflammatory tissue, possibly

through the suppression of Smad2/3 signaling. Our findings partly

clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying BRONJ and would benefit

research into drug targets at the molecular level for the treatment

of this symptom.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid

for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (grant nos. 24791981 awarded to

M.I., 25463053 awarded to N.C., 26462823 awarded to S.K., 22592076

awarded to M.K., 26293426 awarded to T.S., 24593002 awarded to

Y.S., and 26670852 awarded to A.I.) from the Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; Grant-in-Aid from

the Dental Society of Iwate Medical University; and Grant-in-Aid

for Strategic Medical Science Research Centre from the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan,

2010–2014.

Abbreviations:

|

BPs

|

bisphosphonates

|

|

ZA

|

zoledronic acid

|

|

BRONJ

|

BPs-related osteonecrosis of the

jaw

|

|

ECs

|

epithelial cells

|

|

GFs

|

gingival fibroblasts

|

|

hGFs

|

human GFs

|

|

TGF-β

|

transforming growth factor-β

|

|

BMP

|

bone morphogenetic protein

|

|

GDF

|

growth and differentiation factor

|

|

MIS

|

Mullerian inhibiting substance

|

|

R-Smads

|

receptor-regulated Smads

|

|

Co-Smad

|

common mediator Smad

|

|

I-Smads

|

inhibitory Smads

|

|

MFs

|

myofibroblasts

|

|

α-SMA

|

α-smooth muscle actin

|

|

MAPKs

|

mitogen-activated protein kinases

|

|

ERK

|

extra-cellular signal-regulated

kinase

|

|

Cmax

|

maximum concentration in serum

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

PBS

|

phosphate-buffered saline

|

|

GAPDH

|

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase

|

|

SDS-PAGE

|

SDS-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis

|

|

JNK

|

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition

|

|

GEF

|

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

|

References

|

1

|

Gong L, Altman RB and Klein TE:

Bisphosphonates pathway. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 21:50–53. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

2

|

Boonyapakorn T, Schirmer I, Reichart PA,

Sturm I and Massenkeil G: Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of

the jaws: prospective study of 80 patients with multiple myeloma

and other malignancies. Oral Oncol. 44:857–869. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fliefel R, Tröltzsch M, Kühnisch J,

Ehrenfeld M and Otto S: Treatment strategies and outcomes of

bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) with

characterization of patients: a systematic review. Int J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 44:568–585. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Manaka K, Makita N and Iiri T:

Erdheim-Chester disease and pituitary involvement: a unique case

and the literature. Endocr J. 61:185–194. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rogers MJ, Crockett JC, Coxon FP and

Mönkkönen J: Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of action of

bisphosphonates. Bone. 49:34–41. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Vahtsevanos K, Kyrgidis A, Verrou E,

Katodritou E, Triaridis S, Andreadis CG, Boukovinas I, Koloutsos

GE, Teleioudis Z, Kitikidou K, et al: Longitudinal cohort study of

risk factors in cancer patients of bisphosphonate-related

osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Clin Oncol. 27:5356–5362. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M and Broumand

V: Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone

(osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors,

recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

63:1567–1575. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA,

Landesberg R, Marx RE and Mehrotra B; American Association of Oral

and Maxillofacial Surgeons: American Association of Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related

osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 67(Suppl 5):

2–12. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hansen T, Kunkel M, Weber A and James

Kirkpatrick C: Osteonecrosis of the jaws in patients treated with

bisphosphonates-histomorpholoic analysis in comparison with

infected osteoradionecrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 35:155–160. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hoefert S, Wierich W, Eufinger H and

Krempien B: BP-associated vascular necrosis (AN) of the jaws:

histological findings. Bone. 38(suppl 1): 762006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

De Ceulaer J, Tacconelli E and

Vandecasteele SJ: Actinomyces osteomyelitis in

bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ): the

missing link? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 33:1873–1880. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kobayashi Y, Hiraga T, Ueda A, Wang L,

Matsumoto-Nakano M, Hata K, Yatani H and Yoneda T: Zoledronic acid

delays wound healing of the tooth extraction socket, inhibits oral

epithelial cell migration, and promotes proliferation and adhesion

to hydroxyapatite of oral bacteria, without causing osteonecrosis

of the jaw, in mice. J Bone Miner Metab. 28:165–175. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Berti-Couto SA, Vasconcelos AC, Iglesias

JE, Figueiredo MA, Salum FG and Cherubini K: Diabetes mellitus and

corticotherapy as risk factors for alendronate-related

osteonecrosis of the jaws: a study in Wistar rats. Head Neck.

36:84–93. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Molcho S, Peer A, Berg T, Futerman B and

Khamaisi M: Diabetes microvascular disease and the risk for

bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A single center

study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98:E1807–E1812. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nisi M, La Ferla F, Karapetsa D, Gennai S,

Miccoli M, Baggiani A, Graziani F and Gabriele M: Risk factors

influencing BRONJ staging in patients receiving intravenous

bisphosphonates: a multivariate analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac

Surg. 44:586–591. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Valluru M, Staton CA, Reed MWR and Brown

NJ: Transforming growth factor-β and endoglin signaling orchestrate

wound healing. Front Physiol. 2:892011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Tipton DA and Dabbous MK: Autocrine

transforming growth factor β stimulation of extracellular matrix

production by fibroblasts from fibrotic human gingiva. J

Periodontol. 69:609–619. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cotrim P, Martelli-Junior H, Graner E,

Sauk JJ and Coletta RD: Cyclosporin A induces proliferation in

human gingival fibroblasts via induction of transforming growth

factor-beta1. J Periodontol. 74:1625–1633. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu MY and Hill CS: TGF-β superfamily

signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev Cell.

16:329–343. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Goumans MJ, Liu Z and ten Dijke P: TGF-β

signaling in vascular biology and dysfunction. Cell Res.

19:116–127. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Heldin CH, Landström M and Moustakas A:

Mechanism of TGF-β signaling to growth arrest, apoptosis, and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 21:166–176.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu T and Feng XH: Regulation of TGF-β

signalling by protein phosphatases. Biochem J. 430:191–198. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Meulmeester E and Ten Dijke P: The dynamic

roles of TGF-β in cancer. J Pathol. 223:205–218. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Song B, Estrada KD and Lyons KM: Smad

signaling in skeletal development and regeneration. Cytokine Growth

Factor Rev. 20:379–388. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sandbo N and Dulin N: Actin cytoskeleton

in myofibroblast differentiation: ultrastructure defining form and

driving function. Transl Res. 158:181–196. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kimura H, Okubo N, Chosa N, Kyakumoto S,

Kamo M, Miura H and Ishisaki A: EGF positively regulates the

proliferation and migration, and negatively regulates the

myofibroblast differentiation of periodontal ligament-derived

endothelial progenitor cells through MEK/ERK- and JNK-dependent

signals. Cell Physiol Biochem. 32:899–914. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sobral LM, Montan PF, Zecchin KG,

Martelli-Junior H, Vargas PA, Graner E and Coletta RD: Smad7 blocks

transforming growth factor-β1-induced gingival

fibroblast-myofibroblast transition via inhibitory regulation of

Smad2 and connective tissue growth factor. J Periodontol.

82:642–651. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Motizuki M, Isogaya K, Miyake K, Ikushima

H, Kubota T, Miyazono K, Saitoh M and Miyazawa K: Oligodendrocyte

transcription factor 1 (Olig1) is a Smad cofactor involved in cell

motility induced by transforming growth factor-β. J Biol Chem.

288:18911–18922. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Nakano N, Maeyama K, Sakata N, Itoh F,

Akatsu R, Nakata M, Katsu Y, Ikeno S, Togawa Y, Vo Nguyen TT, et

al: C18 ORF1, a novel negative regulator of transforming growth

factor-β signaling. J Biol Chem. 289:12680–12692. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xiao Y-Q, Liu K, Shen J-F, Xu G-T and Ye

W: SB-431542 inhibition of scar formation after filtration surgery

and its potential mechanism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

50:1698–1706. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Bakin AV, Rinehart C, Tomlinson AK and

Arteaga CL: p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for

TGFbeta-mediated fibroblastic transdifferentiation and cell

migration. J Cell Sci. 115:3193–3206. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sarrazy V, Billet F, Micallef L, Coulomb B

and Desmoulière A: Mechanisms of pathological scarring: role of

myofibroblasts and current developments. Wound Repair Regen.

19(Suppl 1): s10–s15. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Van De Water L, Varney S and Tomasek JJ:

Mechanoregulation of the myofibroblast in wound contraction,

scarring, and fibrosis: Opportunities for new therapeutic

intervention. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2:122–141. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hinz B: Formation and function of the

myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol. 127:526–537.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yoshinami T, Yagi T, Sakai D, Sugimoto N

and Imamura F: A case of acquired Fanconi syndrome induced by

zoledronic acid. Intern Med. 50:1075–1079. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kurishima K, Ohara G, Kagohashi K,

Takayashiki N, Tamura T, Shiozawa T, Miyazaki K, Kawaguchi M, Satoh

H and Hizawa N: Ossification and increased bone mineral density

with zoledronic acid in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma: a case

report. Exp Ther Med. 8:1267–1270. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

DeMaio L, Buckley ST, Krishnaveni MS,

Flodby P, Dubourd M, Banfalvi A, Xing Y, Ehrhardt C, Minoo P, Zhou

B, et al: Ligand-independent transforming growth factor-β type I

receptor signalling mediates type I collagen-induced

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Pathol. 226:633–644. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Xu X, Wan X, Geng J, Li F, Wang C and Dai

H: Kinase inhibitors fail to induce mesenchymal-epithelial

transition in fibroblasts from fibrotic lung tissue. Int J Mol Med.

32:430–438. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sawada S, Chosa N, Ishisaki A and Naruishi

K: Enhancement of gingival inflammation induced by synergism of

IL-1β and IL-6. Biomed Res. 34:31–40. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang X, Chu J, Wen CJ, Fu SB, Qian YL, Wo

Y, Wang C and Wang DR: Functional characterization of TRAP1-like

protein involved in modulating fibrotic processes mediated by

TGF-β/Smad signaling in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Exp Cell

Res. 332:202–211. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lu Q: Transforming growth factor-beta1

protects against pulmonary artery endothelial cell apoptosis via

ALK5. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 295:L123–L133. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Pan B, To LB, Farrugia AN, Findlay DM,

Green J, Gronthos S, Evdokiou A, Lynch K, Atkins GJ and Zannettino

AC: The nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid,

increases mineralisation of human bone-derived cells in vitro.

Bone. 34:112–123. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Koch FP, Merkel C, Al-Nawas B, Smeets R,

Ziebart T, Walter C and Wagner W: Zoledronate, ibandronate and

clodronate enhance osteoblast differentiation in a dose dependent

manner - a quantitative in vitro gene expression analysis of Dlx5,

Runx2, OCN, MSX1 and MSX2. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 39:562–569.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen YJ, Chao KS, Yang YC, Hsu ML, Lin CP

and Chen YY: Zoledronic acid, an aminobisphosphonate, modulates

differentiation and maturation of human dendritic cells.

Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 31:499–508. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pabst AM, Ziebart T, Koch FP, Taylor KY,

Al-Nawas B and Walter C: The influence of bisphosphonates on

viability, migration, and apoptosis of human oral keratinocytes -

in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 16:87–93. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Tarnawski AS: Cellular and molecular

mechanisms of gastrointestinal ulcer healing. Dig Dis Sci. 50(Suppl

1): S24–S33. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ozdamar B, Bose R, Barrios-Rodiles M, Wang

HR, Zhang Y and Wrana JL: Regulation of the polarity protein Par6

by TGFbeta receptors controls epithelial cell plasticity. Science.

307:1603–1609. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tojkander S, Gateva G and Lappalainen P:

Actin stress fibers - assembly, dynamics and biological roles. J

Cell Sci. 125:1855–1864. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Saito T, Izumi K, Shiomi A, Uenoyama A,

Ohnuki H, Kato H, Terada M, Nozawa-Inoue K, Kawano Y, Takagi R and

Maeda T: Zoledronic acid impairs re-epithelialization through

down-regulation of integrin αvβ6 and transforming growth factor

beta signalling in a three-dimensional in vitro wound healing

model. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 43:373–380. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Okamoto S, Jiang Y, Kawamura K, Shingyoji

M, Tada Y, Sekine I, Takiguchi Y, Tatsumi K, Kobayashi H, Shimada

H, et al: Zoledronic acid induces apoptosis and S-phase arrest in

mesothelioma through inhibiting Rab family proteins and

topoisomerase II actions. Cell Death Dis. 5:e15172014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Aloisi AL and Bucci C: Rab GTPases-cargo

direct interactions: fine modulators of intracellular trafficking.

Histol Histopathol. 28:839–849. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hu H, Milstein M, Bliss JM, Thai M,

Malhotra G, Huynh LC and Colicelli J: Integration of transforming

growth factor beta and RAS signaling silences a RAB5 guanine

nucleotide exchange factor and enhances growth factor-directed cell

migration. Mol Cell Biol. 28:1573–1583. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kardassis D, Murphy C, Fotsis T, Moustakas

A and Stournaras C: Control of transforming growth factor β signal

transduction by small GTPases. FEBS J. 276:2947–2965. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Short M, Nemenoff RA, Zawada WM, Stenmark

KR and Das M: Hypoxia induces differentiation of pulmonary artery

adventitial fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 286:C416–C425. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|