Introduction

Cartilages are avascular, tough, flexible, fibrous

connective tissues that have multiple roles. Transient cartilages

are a major component of embryonic skeletons and offer a model for

bone formation, while permanent cartilages exhibit various

biomechanical characteristics, including elastic cartilage, hyaline

cartilage and fibrocartilage (1).

The present study focused on articular cartilage, a sort of hyaline

cartilage, which serves crucial roles in supporting and allotting

forces that emerge during joint loading, and supplying a

frictionless lubricating surface to protect the joint from wear or

degradation (2). On account of

the deficiency of nerves, blood vessels, and the inherently poor

differentiating ability of chondrocytes, damaged articular

cartilage has an extremely limited capacity to self-heal (3,4).

Finally, these cartilage injuries result in premature joint

degeneration and posttraumatic arthritis (5). Despite the development of numerous

methods for the restoration of cartilage lesions, some shortcomings

remain (6). Therefore, the search

for novel therapies with low cost, stable activity and security for

cartilage injuries is required.

Herb Epimedium (HEP), a traditional Chinese

medicine, has been widely used for arthritis treatment in China,

Korea and Japan (7,8). Icariin is the major effective

constituent of HEP (9,10). Research has indicated that icariin

promoted osteoblast differentiation through inducing BMP-2, BMP-4

and SMAD4 expression (11).

Additionally, in bone tissue engineering, a study by Zhao et

al (12) demonstrated

efficient osteoinductivity of icariin that was able to enhance

in vivo bone formation. In a murine model of dexamethasone

(DXM)-induced osteoporosis, icariin exerted protective effects

against bone deteriorations and promoted bone remodeling, with

significant decreases in bone resorption markers C-terminal

telopeptide of type II collagen (CTX-II) and tartrate-resistant

acid phosphatase (TRAP)-5b being observed (13). Icariin has been demonstrated to be

a safe and powerful chondrocyte anabolic agent to stimulate

chondrocyte proliferation and attenuate extracellular matrix (ECM)

degradation (14,15). ECM, in response to the properties

of cartilage, is synthesized by chondrocytes (16), thus icariin may be a potential

catalyst for chondrogenesis in cartilage tissue engineering. In the

present study, the effects of icariin were assessed in a rat model

of DXM-induced cartilage injury.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments and drug

administration

A total of 90 6-week-old male Wistar rats, weighing

160–230 g, were obtained from the Centre of Laboratory Animals of

Harbin Medical University (Harbin, China). The rats were given free

access to food and water and were caged individually in a

controlled temperature (21–22°C) in 50–60% humidity, with an

artificial light cycle (12-h light/dark). All rats were acclimated

for 5 days and randomized into the following three groups

(n=10/group): vehicle (control), DXM, and icariin (DXM group

treated with icariin). The vehicle group received normal feed for

12 weeks; the DXM group were injected intramuscularly with 5 mg/kg

body weight DXM (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany)

three times a week for 12 weeks; rats in the icariin group were

dosed orally for 12 weeks with icariin (100 mg/kg/day;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) combined with DXM for 12 weeks. The

animal protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of

Animal Experiments of Harbin Medical University.

Cell culture

Articular chondrocytes were isolated from the knee

joints of rats in the vehicle group as previously described

(17), with some alterations.

Articular cartilage tissues were cut into small pieces (<1

mm3) and digested with 0.2% trypsin and 0.2% type II

collagenase for 30 min and 2 h, respectively. The released cells

were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere of CO2 in air. When the

cells reached ~90% confluence, they were treated with various

concentrations of DXM (0, 10, 50 and 100 µM) for 48 h at

37°C. For miR-206 inhibitor treatment, cells were transfected with

anti-miR-206 inhibitor (200 nM; Riboxx GmbH, Radebeul, Germany)

using GeneCellin transfection reagent (BioCellChallenge, Toulon,

France), according to manufacturer's instructions. A total of 48 h

after transfection, cells were harvested and used for further

experiments. The sequence of the miR-206 inhibitor was

5′-CCACACACUUCCUUACAUUCCA-3′.

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was performed as previously reported

(18), with some changes.

Briefly, the cartilage tissues were crushed under liquid nitrogen

conditions and total RNA extraction was performed with TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA), according to manufacturer's instructions. Samples (1

µg RNA) were reverse-transcribed using a Reverse

Transcription System for real-time PCR (Takara Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd., Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Synthesized cDNA was used in qPCR experiments using SsoFast™

EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

qPCR was performed with the following primers: alkaline phosphatase

(ALP) sense, 5′-GCCCTCTCCAAGACATATA-3′ and antisense,

5′-CCATGATCACGTCGATATCC-3′; TRAP sense, 5′-AGATCTCCAAGCGCTGGAAC-3′

and antisense, 5′-AGGTAGCCGTTGGGGACCTT-3′; osteocalcin sense,

5′-ATGAGAGCCCTCACACTCCTC-3′ and antisense,

5′-CTAGACCGGGCCGTAGAAGCG-3′; cathepsin K sense,

5′-GGGAGACATGACCAGCGAAG-3′ and antisense,

5′-CTGAAAGCCCAACAGGAACC-3′; collagen type I (Col-1) sense,

5′-TCCTGCCGATGTCGCTATC-3′ and antisense,

5′-CCATGTAGGCTACGCTGTTCTTG-3′; matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13

sense, 5′-CCCTGGAGCCCTGATGTTT-3′ and antisense,

5′-CTCTGGTGTTTTGGGGTGCT-3′; transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1

sense, 5′-CCAAGGAGACGGAATACAGG-3′ and antisense,

5′-GTGTTGGTTGTAGAGGGCAAG-3′; miR-612 sense,

5′-CAGGGCTTCTGAGCTCCTTA-3′ and antisense,

5′-TGAGAGTCCTGTCCTGGCTG-3′; miR-206 sense,

5′-GATTCGCCAAAGGAAATAGC-3′ and antisense,

5′-GTTACAAGGTCATCCAAGAC-3′; miR-28-5p sense,

5′-GTGCACTGTCACGGGTTTTC-3′ and antisense, 5′-CCTCTGCAGCCTGGTGAC-3′;

miR-714 sense, 5′-CTGCAAGGGTGGAGGTGTAG-3′ and antisense,

5′-AGGCAGTGGTCTAAACTCGC-3′; miR-7a sense,

5′-TGTTGGCCTAGTTCTGTGTGG-3′ and antisense,

5′-GGCAGACTGTGATTTGTTGTCG-3′; miR-365 sense,

5′-AAATGAGGGACTTTCAGGGGC-3′ and antisense,

5′-AACAATAAGGATTTTTAGGGGCATT-3′; and GAPDH sense, 5′-GTCGGTGTGAAC

GGATTTG-3′ and antisense, 5′-CTTGCGTGGGTAGAGTCAT-3′. qPCR

amplification was performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C

for 5 min, followed by 27 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min

and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min.

Results were analyzed with Opticon Monitor software 3.1 (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Specificity was determined by 1% agarose gel

electrophoretic analysis of the reaction products. GAPDH was used

as an internal standard. Data were analyzed using the

2−ΔΔCq method, as previously described (19).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously

reported (20). Briefly, proteins

were extracted by lysing cells in buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM

NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1

mM phenyl methylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 mg/ml leupeptin and 25 mg/ml

aprotinin). Protein concentration was determined using a

bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Subsequently, proteins (20 µg) were separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE mini-gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride

membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 60 min at 100 V.

Following incubation in blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline

containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 nM Tris and 0.05% Tween-20; pH 7.5) for

1 h at room temperature, the membrane was hybridized in blocking

buffer with specific primary antibodies against cathepsin K

(sc-48353; 1:100), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2; sc-56015; 1:50),

Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax; sc-70407; 1:200), caspase-3

(sc-271759; 1:200), caspase-9 (sc-8355; 1:200) and β-actin

(sc-70319; 1:200) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was

incubated with secondary antibodies labeled with horseradish

peroxidase (sc-516102; 1:200) for 1 h at room temperature, followed

by detection with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE

Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). All antibodies were obtained from

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). β-actin was used

as the protein loading control. Band intensities were quantified by

immunoblot densitometry using Image-Pro Plus 4.5 (Media

Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

Serum biochemical markers of cartilage

metabolism

Anesthetized rats were placed in a euthanasia

chamber. Directly after aspiration, blood was transferred to plain

tubes. Serum was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C, and

stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum levels of CTX-II and

deoxypyridinoline (DPD) were measured using a rat ELISA assay

(60-2700; Immutopics, Inc., San Clemente, CA, USA), as previously

described (21).

Histomorphological analysis

Cartilage tissues were dissected along the axial

plane into pieces of 10×5×7 mm with a thin layer of subchondral

bone and were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for over 24 h at room

temperature. Following decalcification in 10% EDTA solution for

over 2 weeks, the samples were embedded in paraffin. The specimens

were cut into 4-µm sections and stained with safranin-O for

5 min at room temperature. To evaluate the volume of cartilage

formation, the area occupied by chondrocytes and cartilage matrix

stained with safranin-O was quantified using an image analysis

system (ImageJ version 1.43u; National Institutes of Health,

Bethesda, MD, USA).

Luciferase activity assay

The potential binding sites between cathepsin K and

miR-206 were predicted using TargetScan (targetscan.org/mamm_31/). A luciferase assay was used

to validate cathepsin K as a target of miR-206. Articular

chondrocytes (~7.5×104 cells/well) were seeded in

12-well plates, then transfected with the wild-type, mutant

cathepsin K 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) or the vector alone

(co-transfected using pGL3-control) using Lipofectamine 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), in accordance with

the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h, cells were lysed, then

the firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured

using the dual luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI,

USA) on a luminometer (Orion II Microplate Luminometer; Berthold

Detection Systems GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany). To check the

specificity of the miR-206 effect, chondrocytes were co-transfected

with wild-type cathepsin K 3′UTR or miR-206 before luciferase

activities were measured. Control cells were transfected with the

scramble sequence. Renilla reporter luciferase activity was

normalized to the firefly luciferase activity.

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell viability was assessed by LIVE/DEAD assay as

previously reported (22).

Briefly, cells were stained using a LIVE/DEAD stain kit (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. This kit contains two fluorescent dyes, calcein-AM to

stain living cells green and ethidium homodimer-1 (Ethd-1) to stain

dead cells red. Following staining, samples were observed through

an epifluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany)

at a magnification of ×200. For each well, at least five different

fields were examined, and a minimum of 1,000 cells were counted to

determine the fraction of calcein-AM-positive cells vs.

Ethd-1-positive cells.

In addition, to evaluate apoptotic activity of

chondrocytes, terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase-mediated dUTP

nick end labelling (TUNEL) staining was performed, as previously

described (23). Frozen cartilage

sections were fixed with 4% methanol-free formaldehyde solution in

PBS for 10 min at room temperature, then washed with PBS three

times. The DNA fragments were labeled with fluorescein-12-dUTP in

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase incubation buffer (Promega)

in a humidified chamber (37°C for 60 min) to avoid exposure to

light. The reactions were stopped by transferring the slides to SSC

buffer (0.3 M NaCl, 0.03 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) for 15 min and

washing with PBS to remove unincorporated fluorescein-12-dUTP. The

slides were then counterstained with 1 μg/ml

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories, Inc.,

Burlingame, CA, USA) for 5 min at room temperature to provide a

blue background. The green fluorescence of apoptotic cells

(fluorescein-12-dUTP) may be detected using a fluorescence

microscope at 520 nm.

Caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was evaluated as previously

reported (24). Assays were

performed in 96-well microtiter plates by incubating 20 µg

cell lysate in 100 µl reaction buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mM

Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 137 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol) containing 5

µM caspase-3 substrate (Ac-DEVD-pNA; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA). Lysates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Subsequently, the

absorbance was measured at 405 nm with a spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted at least three times.

Data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Statistical analyses were performed using PRISM version 4.0

(GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The differences among

groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by

Tukey's multiple comparison test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of icariin on biomarkers of bone

metabolism in experimental rats

The expression of biochemical markers of bone

turnover in the three experimental groups, including TRAP as a bone

resorption marker, and ALP and osteocalcin as bone formation

markers, were first determined using RT-qPCR. Compared with the

vehicle control group, the DXM group demonstrated significantly

increased expression of ALP and TRAP; however, icariin treatment

significantly eliminated the enhancing effect of DXM on the

expression of ALP and TRAP compared with the DXM group (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, icariin

significantly stimulated osteocalcin expression following DXM

treatment compared with the levels observed in the DXM treatment

group (Fig. 1C). Additionally, it

was also determined that icariin abolished the promotion effect of

DXM on cathepsin K expression, an enzyme expressed by osteoclasts

in response to bone resorption, at the mRNA and protein expression

levels (Fig. 1D and E).

| Figure 1mRNA expression of (A) ALP, (B) TRAP,

(C) osteocalcin and (D) cathepsin K in the three experimental

groups measured by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction. Compared with the vehicle control group, the DXM

group demonstrated significantly increased expression levels of

ALP, TRAP and cathepsin K, and decreased osteocalcin expression.

However, icariin treatment significantly eliminated the enhancing

effect of DXM on the expression of ALP, TRAP and cathepsin K, and

stimulated osteocalcin expression. (E) Protein expression of

cathepsin K in the three experimental groups measured by western

blotting. Icariin significantly abolished the promotion effect of

DXM on cathepsin K. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard

error of the mean (n=10/group). ***P<0.001 vs.

vehicle group; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001

vs. DXM group. ALP, alkaline phosphatase; TRAP, tartrate-resistant

acid phosphatase; DXM, dexamethasone. |

Effects of icariin on cartilage

metabolism in experimental rats

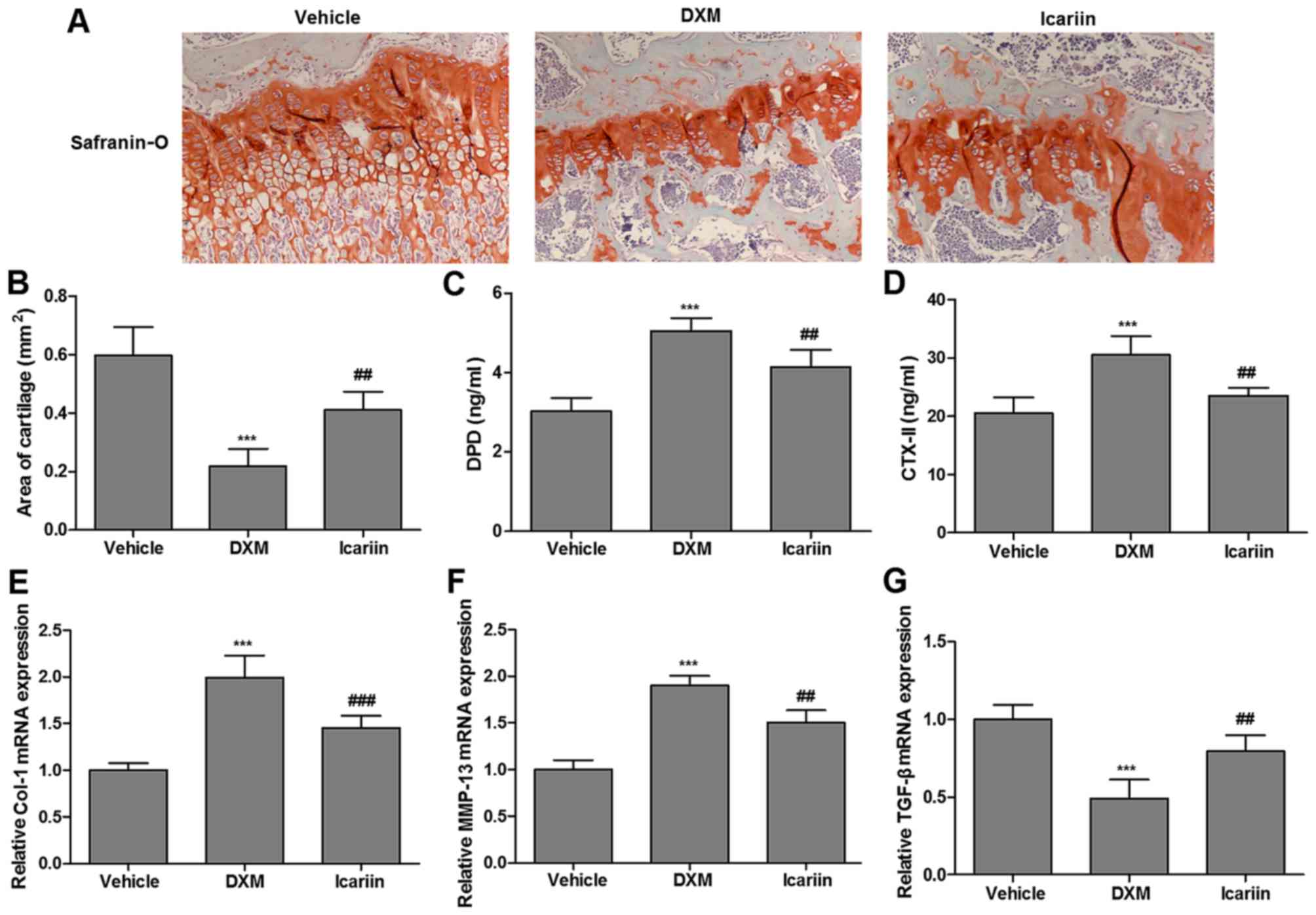

The present study assessed the effects of icariin on

articular cartilage in the three groups. As demonstrated in

Fig. 2A, a small volume of

cartilage formation was observed in the DXM group by safranin-O

staining, relative to the control group; however, continuous

administration of icariin enhanced the volume of cartilage

formation. Similarly, administration of icariin to DXM-treated rats

significantly elevated the reduced cartilage area (occupied by

chondrocytes and cartilage matrix dyed with safranin-O; Fig. 2B). More importantly, icariin

significantly reversed the DXM-induced increase in serum

concentrations of DPD and CTX-II, the commonly used serum markers

of cartilage metabolism, in experimental rats (Fig. 2C and D). Furthermore, the

expression of Col-1, MMP-13 and TGF-β in the three experimental

groups, which are cartilage metabolism-related genes, were

determined. Icariin significantly reduced the elevated expression

of Col-1 and MMP-13 induced by DXM, but promoted TGF-β expression

(Fig. 2E–G).

Validation of dysregulated microRNA

(miRNA) in articular cartilage of experimental rats

The results in Fig.

2 demonstrated the beneficial effect of icariin on cartilage

metabolism in DXM-treated rats, thus it was speculated whether

icariin affected articular cartilage of experimental rats at the

miRNA level. The relative expression of the miRNA in articular

cartilage of all experimental rats were presented as a heatmap

(Fig. 3A). The deeper the color,

the higher the expression. A total of five miRNA were further

determined to be significantly upregulated in the icariin group,

compared with the reduced levels in the DXM-treated group,

including miR-612, -206, -28-5p, -7a and -365 (Fig. 3B-G). In view of the role of

miR-206 as a key regulator during osteoblast differentiation

(25), miR-206 was selected as

the candidate for the following experiments.

| Figure 3(A) Heatmap of all miR related to

articular cartilage in experimental rats. Red indicates high

relative expression and green indicates low relative expression.

mRNA expression of (B) miR-612, (C) miR-206, (D) miR-28-5p, (E)

miR-714, (F) miR-7a and (G) miR-365 in the three experimental

groups were determined by reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. DXM significantly reduced miR-612,

miR-206, miR-28-5p, miR-7a, miR-714 and miR-365 expression;

however, icariin significantly rescued the expression of these miR,

except for the expression of miR-714. Values are expressed as the

mean ± standard error of the mean. ***P<0.001 vs.

vehicle group; #P<0.05 and ###P<0.001

vs. DXM group. miR, microRNA; DXM, dexamethasone. |

miR-206 targets cathepsin K

To determine whether miR-206 regulated cathepsin K

through the predicted binding sites in its 3′UTR (Fig. 4A), two luciferase constructs were

employed by incorporating wild-type or mutant 3′UTR of cathepsin K,

which expressed luciferase unless repressed by the incorporated

3′UTR. As demonstrated in Fig.

4B, co-transfection with the pMIR-REPORT construct containing

mutant cathepsin K 3′UTR and PLemiR-206 did not exhibit a

significant difference compared with the control; however,

co-transfection with the luciferase construct containing wild-type

cathepsin K 3′UTR and PLemiR-206 resulted in an ~70% decline in

luciferase activity compared with the control. As demonstrated in

Fig. 4C and D, compared with the

control group, miR-206 overexpression significantly decreased the

expression of cathepsin K; however, the inhibition of miR-206

elevated the level of cathepsin K, both at the mRNA and protein

expression levels.

| Figure 4Luciferase activity assay and the

expression of Cstk in chondrocytes. (A) Schematic representation of

the putative miR-206 binding site in the Cstk 3′UTR in TargetScan.

(B) Luciferase activity assay of Cstk. Co-transfection with the

luciferase construct containing wild-type Cstk K 3′UTR and

PLemiR-206 resulted in a significant decline in luciferase activity

compared with the control. miR-206 overexpression significantly

decreased the expression of Cstk; however, inhibiting miR-206

elevated the level of Cstk, both at the (C) mRNA and (D) protein

levels. mRNA expression of Cstk was measured by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and protein

expression was measured by western blotting. Values are expressed

as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01 vs. con or NC group;

&&&P<0.001 vs. scramble group. Cstk,

cathepsin K; UTR, untranslated region; Con, control; NC, normal

control; miR, microRNA; wild, wild-type; Mut, mutant. |

Effects of icariin on chondrocytes in

experimental rats and the implicated molecular mechanism

Finally, the present study assessed the effects of

icariin on chondrocytes in the presence of DXM at the indicated

concentrations (Fig. 5). As

demonstrated in Fig. 5A, the

addition of DXM (100 µM) to chondrocytes resulted in a

maximum reduction in cell viability compared with the control

cells; however, this effect was reversed significantly following

treatment with icariin (100 µM). As demonstrated in Fig. 5B and C, icariin (100 µM)

significantly suppressed DXM-induced elevation of chondrocyte

apoptosis, accompanied by an increase in the level of Bcl-2, and

decreases in the levels of Bax, caspase-3 and caspase-9 (Fig. 5D). RT-qPCR further indicated that

icariin (100 µM) abolished the maximal inhibition effect of

DXM (100 µM) on miR-206 expression in chondrocytes (Fig. 5E). Additionally, Fig. 5F and G demonstrated that the

dose-dependent addition of DXM significantly elevated the

expression of cathepsin K, which peaked at a dose of 100 µM.

This level was significantly decreased following icariin

stimulation (100 µM).

Discussion

In bone tissue engineering, the effect of icariin on

bone metabolism is of interest, including the stimulation of bone

formation and osteoblast differentiation (26), as well as the inhibition of bone

resorption and osteoclast differentiation (27). However, little is known about the

effect of icariin on cartilage tissue and how icariin acts on

cartilage tissue engineering, although icariin has been

demonstrated to stimulate chondrocyte proliferation and reduce ECM

degradation (15). The present

data provided available information about the effect of icariin in

rats with cartilage disease, as well as the implicated mechanism.

Changes in bone markers not only simply predict the response in

bone metabolism (28), but may

also be detected earlier than the alterations in bone mineral

density (29). The present study

first identified that the administration of icariin to DXM-treated

rats significantly decreased bone resorption (reduced expression of

TRAP and cathepsin K), as well as significantly increased the level

of bone formation (elevated expression of osteocalcin), which were

consistent with the results observed in mice with DXM-induced

osteoporosis (13), suggesting a

beneficial effect of icariin on bone generation.

There is increasing evidence supporting the

important role of icariin in cartilage tissue engineering. An in

vivo study of the effect of icariin on cartilage tissue

engineering revealed that icariin stimulated ECM secretion and the

expression of cartilage-related genes of chondrocytes, implying the

possibility of icariin as a promoter in cartilage tissue

engineering (30). A study by Sun

et al (31) reported that

icariin suppressed bone and cartilage deteriorations in mice with

collagen-induced arthritis, suggesting that icariin holds promise

as a treatment for patients with joint diseases. A study by Yuan

et al (32) reported that

integrating icariin into hydrogel scaffolds facilitated the

synthesis of cartilage matrix and improved the quality of newly

formed cartilage. Furthermore, cytokines, particularly TGF-β, have

been demonstrated to be strong regulators of chondrocyte

differentiation and to modulate ECM formation (33,34). A recent study has identified that

icariin stimulated cartilage repair through the activation of

hypoxia inducible factor-1α in chondrocytes (35). It should be noted that DPD and

CTX-II, commonly used serum markers of cartilage metabolism, are

important for cartilage turnover. In the present study, as

expected, it was observed that icariin markedly enhanced cartilage

formation (increased cartilage area) and improved cartilage

metabolism (reduced serum concentrations of DPD and CTX-II, reduced

expression of Col-1 and MMP-13, and elevated expression of TGF-β)

in DXM-treated rats.

More importantly, the present study determined that

miR-206 was significantly upregulated following continuous

administration of icariin to DXM-treated rats, and cathepsin K was

further validated as the target RNA of miR-206. miRNA are small

non-coding RNA that act as key post-transcriptional gene regulators

and are implicated in various biological processes, including

proliferation, development and disease occurrence (36–38). miR-206 has been demonstrated to be

a key regulator during osteoblast differentiation (25). Various studies have explored the

role of miRNA in cartilage development and diseases. A study by

Sumiyoshi et al (39)

discovered a novel role of miR-181a in cartilage metabolism. A

study by Mirzamohammadi et al (40) reported that overexpression of

hsa-miR-148a stimulated cartilage formation by inhibiting

hypertrophic differentiation and inducing type II collagen

production of osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Guérit et al

(41) reported that miR-29a was

greatly downregulated during chondrogenesis and that overexpression

of miR-29a observably inhibited chondrocyte-specific gene

expression during chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem

cells. The present study also revealed that the addition of icariin

(100 µM) to DXM-treated chondrocytes resulted in a

significant increase in cell viability, as well as a significant

reduction in cell apoptosis, which were extremely similar to the

findings in rabbit chondrocytes (42). Additionally, the activation of

miR-206 targeting to cathepsin K following the addition of icariin

(100 µM) to DXM-treated chondrocytes further suggested a

novel miR-206-dependent mechanism that may be responsible for the

chondroprotective efficacy of icariin in DXM-induced cartilage

injuries in rats.

In conclusion, the present results identified

icariin as a potential accelerator exerting protective effects

against cartilage degradation and promoting cartilage regeneration

in a rat model of DXM-induced cartilage injury. The present study

revealed that the activation of miR-206 targeting to cathepsin K,

at least partly, was involved in this mechanism.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the Natural

Science Foundation for Young Scholars of Heilongjiang, China (grant

no. QC20160117).

References

|

1

|

Dang AC and Kuo AC: Cartilage biomechanics

and implications for treatment of cartilage injuries. Oper Tech

Orthop. 24:288–292. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mow VC, Ratcliffe A and Poole AR:

Cartilage and diarthrodial joints as paradigms for hierarchical

materials and structures. Biomaterials. 13:67–97. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Frenkel SR, Clancy RM, Ricci JL, Di Cesare

PE, Rediske JJ and Abramson SB: Effects of nitric oxide on

chondrocyte migration, adhesion, and cytoskeletal assembly.

Arthritis Rheum. 39:1905–1912. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Klein TJ, Rizzi SC, Reichert JC, Georgi N,

Malda J, Schuurman W, Crawford RW and Hutmacher DW: Strategies for

zonal cartilage repair using hydrogels. Macromol Biosci.

9:1049–1058. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Furman BD, Strand J, Hembree WC, Ward BD,

Guilak F and Olson SA: Joint degeneration following closed

intraarticular fracture in the mouse knee: a model of posttraumatic

arthritis. J Orthop Res. 25:578–592. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Seyedin MS and Matava M: Cartilage repair

methods. US Patent. 20070128155 A1. Filed December 7, 2006; issued

June 7, 2007. https://www.google.ms/patents/US20070128155.

|

|

7

|

Yu S, Chen K, Li S and Zhang K: In vitro

and in vivo studies of the effect of a Chinese herb medicine on

osteoclastic bone resorption. Chin J Dent Res. 2:7–11.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang DW, Cheng Y, Wang NL, Zhang JC, Yang

MS and Yao XS: Effects of total flavonoids and flavonol glycosides

from Epimedium koreanum Nakai on the proliferation and

differentiation of primary osteoblasts. Phytomedicine. 15:55–61.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xie F, Wu CF, Lai WP, Yang XJ, Cheung PY,

Yao XS, Leung PC and Wong MS: The osteoprotective effect of Herba

epimedii (HEP) extract in vivo and in vitro. Evid Based Complement

Alternat Med. 2:353–361. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Qian G, Zhang X, Lu L, Wu X, Li S and Meng

J: Regulation of Cbfa1 expression by total flavonoids of Herba

epimedii. Endocr J. 53:87–94. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hsieh TP, Sheu SY, Sun JS, Chen MH and Liu

MH: Icariin isolated from Epimedium pubescens regulates osteoblasts

anabolism through BMP-2, SMAD4, and Cbfa1 expression.

Phytomedicine. 17:414–423. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhao J, Ohba S, Komiyama Y, Shinkai M,

Chung UI and Nagamune T: Icariin: a potential osteoinductive

compound for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A.

16:233–243. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang J, Song J and Shao J: Icariin

attenuates glucocorticoid-induced bone deteriorations, hypocalcemia

and hypercalciuria in mice. Int J Clin Exp Med. 8:7306–7314.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xu CQ, Liu BJ, Wu JF, Xu YC, Duan XH, Cao

YX and Dong JC: Icariin attenuates LPS-induced acute inflammatory

responses: involvement of PI3K/Akt and NF-kappaB signaling pathway.

Eur J Pharmacol. 642:146–153. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu MH, Sun JS, Tsai SW, Sheu SY and Chen

MH: Icariin protects murine chondrocytes from

lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses and extracellular

matrix degradation. Nutr Res. 30:57–65. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Qi WN and Scully SP: Type II collagen

modulates the composition of extracellular matrix synthesized by

articular chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 21:282–289. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhou PH, Liu SQ and Peng H: The effect of

hyaluronic acid on IL-1β-induced chondrocyte apoptosis in a rat

model of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 26:1643–1648. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Matsubara J, Yamada Y, Nakajima TE, Kato

K, Hamaguchi T, Shirao K, Shimada Y and Shimoda T: Clinical

significance of insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor and

epidermal growth factor receptor in patients with advanced gastric

cancer. Oncology. 74:76–83. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kim JE, Lee MH, Nam DH, Song HK, Kang YS,

Lee JE, Kim HW, Cha JJ, Hyun YY, Han SY, et al: Celastrol, an NF-κB

inhibitor, improves insulin resistance and attenuates renal injury

in db/db mice. PLoS One. 8:e62068. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

DeLaurier A, Jackson B, Pfeiffer D, Ingham

K, Horton MA and Price JS: A comparison of methods for measuring

serum and urinary markers of bone metabolism in cats. Res Vet Sci.

77:29–39. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tu Y, Xue H, Francis W, Davies AP,

Pallister I, Kanamarlapudi V and Xia Z: Lactoferrin inhibits

dexamethasone-induced chondrocyte impairment from osteoarthritic

cartilage through up-regulation of extracellular signal-regulated

kinase 1/2 and suppression of FASL, FAS, and caspase 3. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 441:249–255. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhou RR, Jia SF, Zhou Z, Wang Y, Bucana CD

and Kleinerman ES: Adenovirus-E1A gene therapy enhances the in vivo

sensitivity of Ewing's sarcoma to VP-16. Cancer Gene Ther.

9:407–413. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Park JW, Choi YJ, Suh SI, Baek WK, Suh MH,

Jin IN, Min DS, Woo JH, Chang JS, Passaniti A, et al: Bcl-2

overexpression attenuates resveratrol-induced apoptosis in U937

cells by inhibition of caspase-3 activity. Carcinogenesis.

22:1633–1639. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Inose H, Ochi H, Kimura A, Fujita K, Xu R,

Sato S, Iwasaki M, Sunamura S, Takeuchi Y, Fukumoto S, et al: A

microRNA regulatory mechanism of osteoblast differentiation. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:20794–20799. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li XF, Xu H, Zhao YJ, Tang DZ, Xu GH, Holz

J, Wang J, Cheng SD, Shi Q and Wang YJ: Icariin augments bone

formation and reverses the phenotypes of osteoprotegerin-deficient

mice through the activation of Wnt/β-catenin-BMP signaling. Evid

Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013:6523172013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hsieh TP, Sheu SY, Sun JS and Chen MH:

Icariin inhibits osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by

suppression of MAPKs/NF-κB regulated HIF-1α and PGE(2) synthesis.

Phytomedicine. 18:176–185. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mehl B, Delling G, Schlindwein I, Heilmann

P, Voia C, Ziegler R, Nawroth P and Kasperk C: Do markers of bone

metabolism reflect the presence of a high- or low-turnover state of

bone metabolism? Med Klin. 97:588–594. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Terzi T, Terzi M, Tander B, Cantürk F and

Onar M: Changes in bone mineral density and bone metabolism markers

in premenopausal women with multiple sclerosis and the relationship

to clinical variables. J Clin Neurosci. 17:1260–1264. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Guo Y, Wu X and Zhang X, Li D, Xiao Y, Fan

Y and Zhang X: The in vivo study of the effect of icariin on ECM

secretion and gene expression of chondrocytes. Pharmacol Clin Chin

Mater Med. 2012.

|

|

31

|

Sun P, Liu Y, Deng X, Yu C, Dai N, Yuan X,

Chen L, Yu S, Si W, Wang X, et al: An inhibitor of cathepsin K,

icariin suppresses cartilage and bone degradation in mice of

collagen-induced arthritis. Phytomedicine. 20:975–979. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yuan T, He L, Yang J, Zhang L, Xiao Y, Fan

Y and Zhang X: Conjugated icariin promotes tissue-engineered

cartilage formation in hyaluronic acid/collagen hydrogel. Process

Biochem. 50:2242–2250. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Blanco FJ, Geng Y and Lotz M:

Differentiation-dependent effects of IL-1 and TGF-beta on human

articular chondrocyte proliferation are related to inducible nitric

oxide synthase expression. J Immunol. 154:4018–4026.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Roberts AB, Flanders KC, Heine UI,

Jakowlew S, Kondaiah P, Kim SJ and Sporn MB: Transforming growth

factor-beta: multifunctional regulator of differentiation and

development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 327:145–154. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang P, Zhang F, He Q, Wang J, Shiu HT,

Shu Y, Tsang WP, Liang S, Zhao K and Wan C: Flavonoid compound

icariin activates hypoxia inducible factor-1α in chondrocytes and

promotes articular cartilage repair. PLoS One. 11:e01483722016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Shantikumar S, Caporali A and Emanueli C:

Role of microRNAs in diabetes and its cardiovascular complications.

Cardiovasc Res. 93:583–593. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

37

|

Schoolmeesters A, Eklund T, Leake D,

Vermeulen A, Smith Q, Force Aldred S and Fedorov Y: Functional

profiling reveals critical role for miRNA in differentiation of

human mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 4:e56052009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bueno MJ, Pérez de Castro I and Malumbres

M: Control of cell proliferation pathways by microRNAs. Cell Cycle.

7:3143–3148. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sumiyoshi K, Kubota S, Ohgawara T, Kawata

K, Abd El Kader T, Nishida T, Ikeda N, Shimo T, Yamashiro T and

Takigawa M: Novel role of miR-181a in cartilage metabolism. J Cell

Biochem. 114:2094–2100. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mirzamohammadi F, Papaioannou G and

Kobayashi T: MicroRNAs in cartilage development, homeostasis, and

disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 12:410–419. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Guérit D, Brondello JM, Chuchana P,

Philipot D, Toupet K, Bony C, Jorgensen C and Noël D: FOXO3A

regulation by miRNA-29a controls chondrogenic differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells and cartilage formation. Stem Cells Dev.

23:1195–1205. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang L, Zhang X, Li KF, Li DX, Xiao YM,

Fan YJ and Zhang XD: Icariin promotes extracellular matrix

synthesis and gene expression of chondrocytes in vitro. Phytother

Res. 26:1385–1392. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|