With the rapid development of research in the field

of cellular death, it is acknowledged that necrosis can also be

regulated in a programmed manner via a specific signal transduction

pathway called necroptosis or programmed necrosis (1,2).

Necroptosis-mediated cell rupture is morphologically characterized

by the loss of cell plasma membrane and the swelling of organelles

(particularly mitochondria). Nevertheless, necroptosis, a form of

programmed cell death (PCD), and its upstream molecular signaling

pathways are under strict control (3,4).

The initiation of necroptosis requires several different stimuli,

as well as the kinase activity of receptor-interacting

serine/threonine kinase 1 (RIP1) and receptor-interacting

serine/threonine kinase 3 (RIP3) (5).

The present review examined the functions of

RIP1/RIP3-regulated necroptosis on multifaceted pathological

mechanisms. Furthermore, the importance of RIP1/RIP3 in determining

the cell outcome was highlighted by the interactive molecular

pathways noted among cell survival, apoptosis and necroptosis.

Then, the pivotal roles of RIP1/RIP3 in disease treatment were

discussed, highlighting their application potential as new drug

targets.

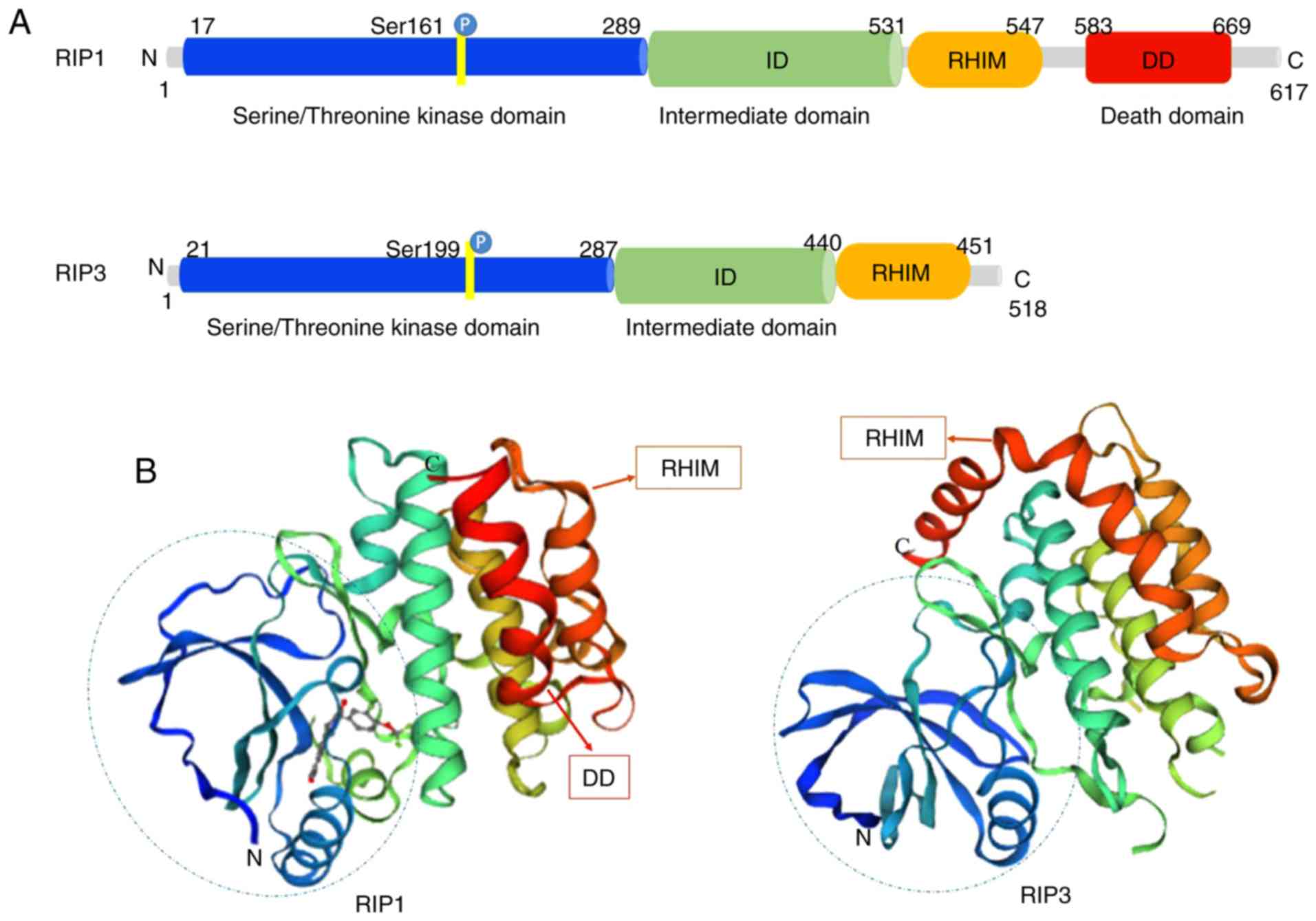

Structurally, RIP1 and RIP3 share nearly half of

their amino acid sequences and have very similar topology features.

The RIP1 protein consists of 671 amino acids (Homo sapiens).

It contains a N-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain, an

intermediate domain (ID), a RHIM and a C-terminal DD (13) (Fig.

1A). RIP3 is composed of 518 amino acids (Homo sapiens),

and contains a N-terminal kinase domain similar to that of RIP1, a

RHIM domain and a unique C-terminus without a DD (14) (Fig.

1A). RIP1 acts as a multifunctional adaptor protein in response

to the activated signal of death receptors (DRs), and its DD binds

to the DRs of TNFR1, Fas and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

(TRAIL) (15,16). It mediates prosurvival NF-κB

activation, caspase-dependent apoptosis and RIP kinase-dependent

necroptosis (17). The ID of RIP1

contains the RHIM that enables the protein to combine with RIP3. In

contrast to RIP1, RIP3 is not directly required for DR-induced cell

survival or death (18). RIP3

binds to RIP1 through its unique C-terminal segment to inhibit RIP1

and TNFR1-mediated NF-κB activation (19) (Fig.

1B). Experiments have revealed that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)

induces the formation of an RIP1/RIP3 complex, indicating that RIP1

interacts with RIP3 through the homotypic RHIM domain (20).

Necroptosis can provide a substitute suicide

mechanism in case of malfunction of the classical apoptosis

machinery (21). Most work on

necroptosis concerns studies of TNF signaling. TNF is a pleiotropic

cytokine that has an essential role in inflammation, tissue injury

and cell death (22). In the TNF

receptor superfamily, researchers have found six human DRs,

including TNFR1, Fas (also known as CD95 or APO-1), DR3 (also known

as TRAMP or APO-3), TRAIL receptor 1 (TRAILR1, also known as DR4),

TRAIL receptor 2 (TRAILR2, also known as DR5, TRICK or KILLER) and

DR6 (also known as CD358) (23-26). However, the most prevalent pathway

is the TNFR1-mediated signal transduction, which can propel cell

survival, apoptosis and necroptosis (27). The present review focused on the

three most dominant of those TNF-mediated pathways.

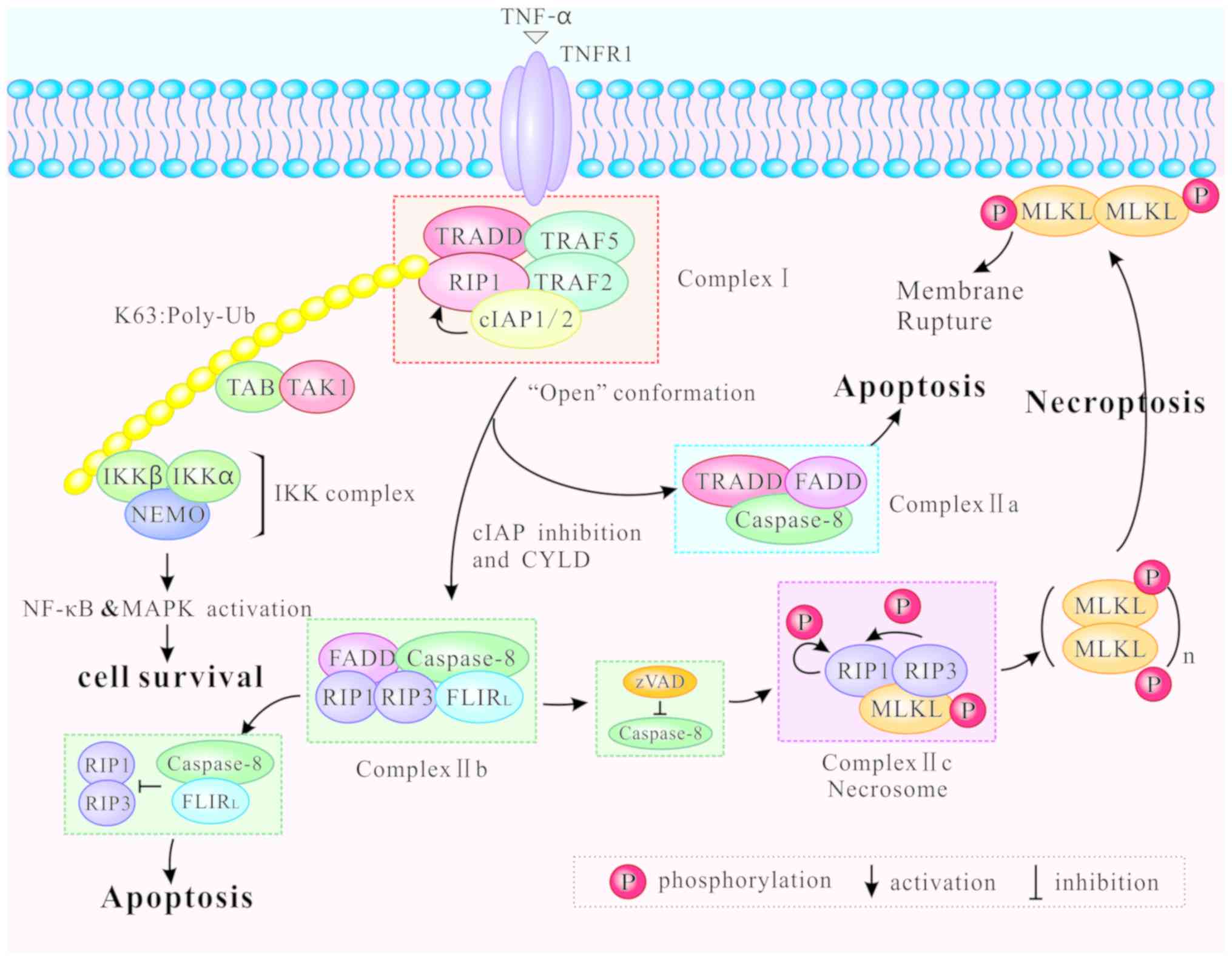

Different modifications of RIP1 can induce distinct

outcomes of cell survival, apoptosis and necroptosis. Following

binding of TNF-α to TNFR1 at the plasma membrane,

TNF-receptor-associated death domain (TRADD) recruits downstream

proteins, namely RIP1, the E3 ubiquitin ligases

TNF-receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 2, TRAF5, and the cellular

inhibitor of apoptosis (cIAP) 1 and cIAP2, to form the complex I

(28,29). Then, the complex I mediates NF-κB

and MAPK signaling, contributing to cell survival or other

non-death functions (4,30,31). The K63-linked ubiquitination of

RIP1 by cIAP1/2 promotes both the formation and activation of the

transforming growth factor-activated kinase 1 (TAK1)-binding

protein (TAB) complex and the inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK)

complex (consisting of NF-κB essential modulator, IKKα and IKKβ),

supporting the NF-κB pathway activation, and ultimately leading to

cell survival (1) (Fig. 2).

Complex I internalizes and transforms into a

death-inducing complex II following caspase-8 activation (29). Two distinct types of complex II

(IIa and IIb) can be distinguished based on their composition and

the activity of their proteins. After dissociating from TNFR1,

TRADD recruits Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) and

further promotes recruitment and activation of caspase-8 to form

the complex IIa (29,32). Activation of caspase-8

subsequently induces apoptosis independently of RIP1 or its kinase

activity (32). In certain

circumstances, including upon the absence of cIAP1/2, upon

inhibition of IAP mediated by a small molecule mimic of diablo

IAP-protein mitochondrial protein (33) and upon auto-degradation of

cIAP1/2, RIP1 is released from complex I to form a

caspase-8-activating complex (complex IIb) which mediates apoptosis

(32). Complex IIb consists of

RIP1, RIP3, FADD and the FLICE-like inhibitory protein long form

(FLIPL)/caspase-8 heterodimer, and it promotes RIP1- and

caspase-8-dependent apoptosis (22). Hence, RIP1 is not an indispensable

factor in apoptosis, although the process is favored by its

presence. Under physiological levels, the caspase-8/FLIPL

heterodimer facilitates caspase-8 oligomer assembly to trigger

apoptosis. By contrast, high levels of FLIPL and FLICE-like

inhibitory protein short form (FLIPS) restrict caspase-8/c-FLIPL/S

heterodimer activity, leading to inhibition of apoptosis (34-36). Inactivation of RIP1 and RIP3,

mediated by cleavage via caspase-8/FLIPL heterodimer in Complex

IIb, inhibits necroptosis (37,38) (Fig.

2).

When caspase-8 is inhibited by zVAD, RIP1 and RIP3

are combined via the RHIM, and form complex IIc, also known as the

necrosome (39). Complex IIc is a

crucial cytoplasmic signaling complex, which does not appear in the

TNF-induced cell survival or apoptosis (10,40). Mitochondrial reactive oxygen

species (ROS) oxidize RIP1 at three crucial cysteine sites (C257,

C268 and C586), and promote autophosphorylation of RIP1 at Ser161.

RIP1 autophosphorylation is pivotal for the recruitment of RIP3

(41). In addition, CYLD lysine

63 deubiquitinase (CYLD), as a deubiquitinase removing

polyubiquitin chains from RIP1, facilitates the formation and

activation of RIP1/RIP3 necrosomes by deubiquitylating RIP1. When

CYLD is deficient, necrosomes promote a high level of ubiquitinated

RIP1 and block phosphorylation of RIP1 and RIP3 (32,42). Furthermore, the RHIM is also

required for the RIP1/RIP3 complex formation (19). After RIP1 and RIP3 are combined,

RIP1 gets phosphorylated by RIP3 (10). Intramolecular auto- and

trans-phosphorylation of RIP1/RIP3 promotes recruitment of another

key necroptosis-signaling protein, the mixed lineage kinase domain

like protein (MLKL). MLKL is then phosphorylated by RIP3 to

initiate necroptosis (43). The

phosphorylated MLKL is transferred from the cytosol to the plasma

and intracellular membranes via the four helical bundle-brace

(4HBD-BR) regions of MLKL (44).

The oligomerization of MLKL causes membrane pore formation,

resulting in the destruction of membrane integrity and eventually

leading to necrotic death (45)

(Fig. 2).

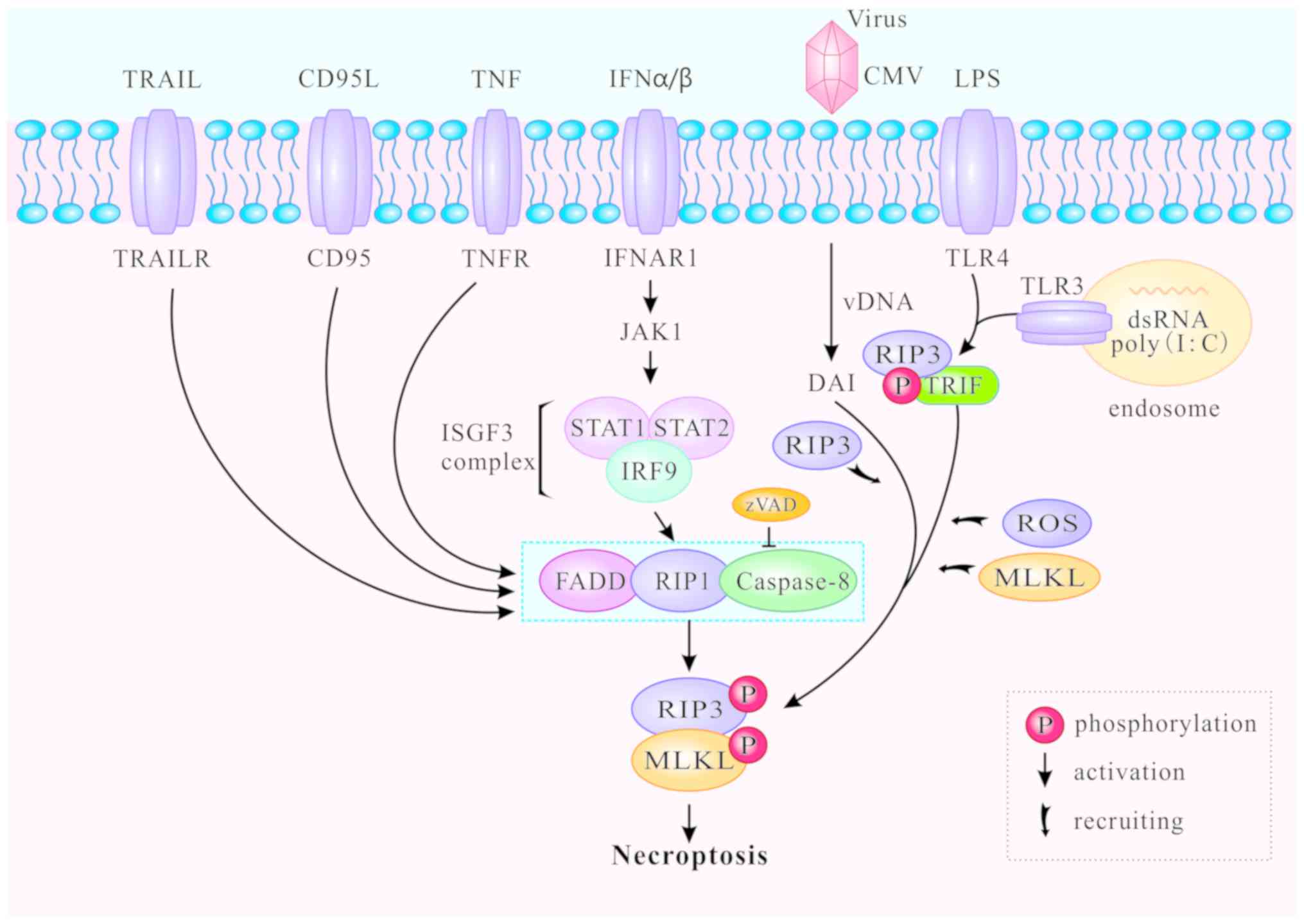

In addition to the classic TNFR1-induced necroptosis

pathway described above, toll-like receptors (TLR) can also mediate

necroptosis. The TLR signaling pathway is generally triggered by

pathogen-associated molecular patterns during viral or microbial

infection (46,47). TLR-mediated necroptosis results in

the destruction of infected cells and is thus beneficial to the

host. The downstream MLKL signaling pathway of RIP3 is

indispensable for both TNFR1- and TLR-induced signaling (46), and caspase-8 can block necroptosis

that is directly initiated by the TIR domain-containing

interferon-β (TRIF)/RIP3/MLKL pathway (48,49). TLR4 and TLR3 are respectively

activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (50) and polyinosine-polycytidylic acid

(I:C), a synthetic double stranded RNA (dsRNA) mimic (51). Thereafter, TLR3 and TLR4 activate

RIP3 and participate in ensuing necroptosis via TRIF or MyD88

(52-54). The C-terminal RHIM motif is

required for RIP3 to interact with TRIF or MyD88. The RIP3/TRIF

signaling complex recruits and phosphorylates MLKL, inducing ROS

accumulation and mediating TLR3- and TLR4-induced necroptosis

(46,47) (Fig.

3).

Increasing numbers of necroptotic stimuli have been

identified and divided into two groups: RIP1-dependent and

RIP1-independent (Fig. 3).

RIP1-dependent stimuli include TNF-α, Fas, TRAIL, interferon

(IFN)-α and IFN-β. The primary death-inducing signaling complex

(DISC) is assembled by stimulation of Fas or TRAILR at the plasma

membrane, thereby activating caspase-8 and triggering apoptosis

independently of RIP1 (55). cIAP

deficiency promotes the recruitment of RIP1 and Fas when caspase-8

is blocked, and enhances the formation of the cytosolic ripoptosome

complex which induces necroptosis (56). In bone-marrow-derived macrophages,

type I IFNα and IFNβ bind to their cognate receptor IFNα/β receptor

subunit 1 (IFNAR1) to activate Janus kinase 1 and form the

IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex (consisting of STAT1,

STAT and IFN-regulatory factor 9). The ISGF3 complex promotes

induction and activation of necrosomes, and triggers necroptosis in

a transcription-dependent pathway (57). RIP1-independent stimuli generally

refer to LPS, dsRNA and viruses. DNA-dependent activator of IFN

regulatory factors (DAI) can identify viral dsRNA, promote the

recruitment of RIP3 to form necrosomes without RIP1, and induce

RIP3-dependent necroptosis (58).

Illuminating the molecular mechanisms involved in necroptosis will

elucidate further the molecular biology underlying the

pathology.

RIP1 and RIP3 were recently delineated as two

important effectors in the cell death network, as they are cascade

proteins responding to complex TNFR signaling and regulating

cellular survival, apoptosis and necroptosis. It is important to

note that RIP3 is indispensable for necroptosis, whereas RIP1 is

not. TNF-α-induced RIP1/RIP3 interaction engages RIP3 recruitment,

leading to RIP3/RIP3 homo-oligomerization and RIP3

autophosphorylation. Phosphorylated RIP3 recruits and

phosphorylates MLKL, which promotes MLKL oligomer-executed

necroptosis (59). However, the

directorial functions of RIP1 are not always positive for RIP3.

Researchers have constructed RIP3 dimers and RIP3 oligomers to

analyze how RIP1 induces the activation of RIP3 (60). The results demonstrated that the

dimerization of RIP3 alone was insufficient to induce the cell

death. The RIP3 dimer seeded a RHIM-dependent complex controlled by

both caspase-8 and RIP1. On the other hand, without TNF stimulation

and RIP1 activity, the oligomerization of RIP3 was sufficient to

induce necroptosis (60). These

results indicated that RIP1 not only activates RIP3 in response to

TNF signaling, but also participates in cytoprotection. TNFR1

promotes the activation of the NF-κB pathway, p38α and its

downstream effector MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 kinase (MK2),

thereby promoting cell survival (61). Recently, Jaco et al

(62) reported that activated MK2

phosphorylated RIP1 at Ser321 to synergize TNF-induced cell rescue.

Therefore, these results suggest that RIP1 serves as a positive

checkpoint within TNF stimulation that integrates cytokine

production and cell survival. RIP1 is therefore thought as an

inhibitor rather than an initiator of RIP3-induced necroptosis

(63).

Furthermore, ROS participate in the regulation of

necroptosis in many cell types, and enhance the formation of

necrosomes induced by Smac mimetic bivalent 6 compound (BV6)/TNFα

(64). BV6/TNFα-stimulated ROS

generation promotes the stabilization of the RIP1/RIP3 feedback

loop. A previous study demonstrated that the metabolic enzymes

glycogen phosphorylase (PYGL), glutamate dehydrogenase 1 (GLUD1),

and glutamate-ammonia ligase (GLUL), are activated by RIP3

(65). Enhancement of aerobic

respiration is mediated by TNF-induced ROS. However, the major

mechanism of ROS and RIP1/RIP3 remains not completely understood. A

recent study demonstrated that mitochondrial ROS activated RIP1

autophosphorylation at Ser161 via oxidation of three crucial

cysteines in RIP1 (41). This

phosphorylation accelerated RIP1 recruitment of the RIP3

aggregation and formed a necrosome, which then resulted in

mitochondrial depolarization and cell necroptosis (66). These studies provided essential

insight into the reciprocal regulation between RIP1/RIP3 and ROS in

necroptosis.

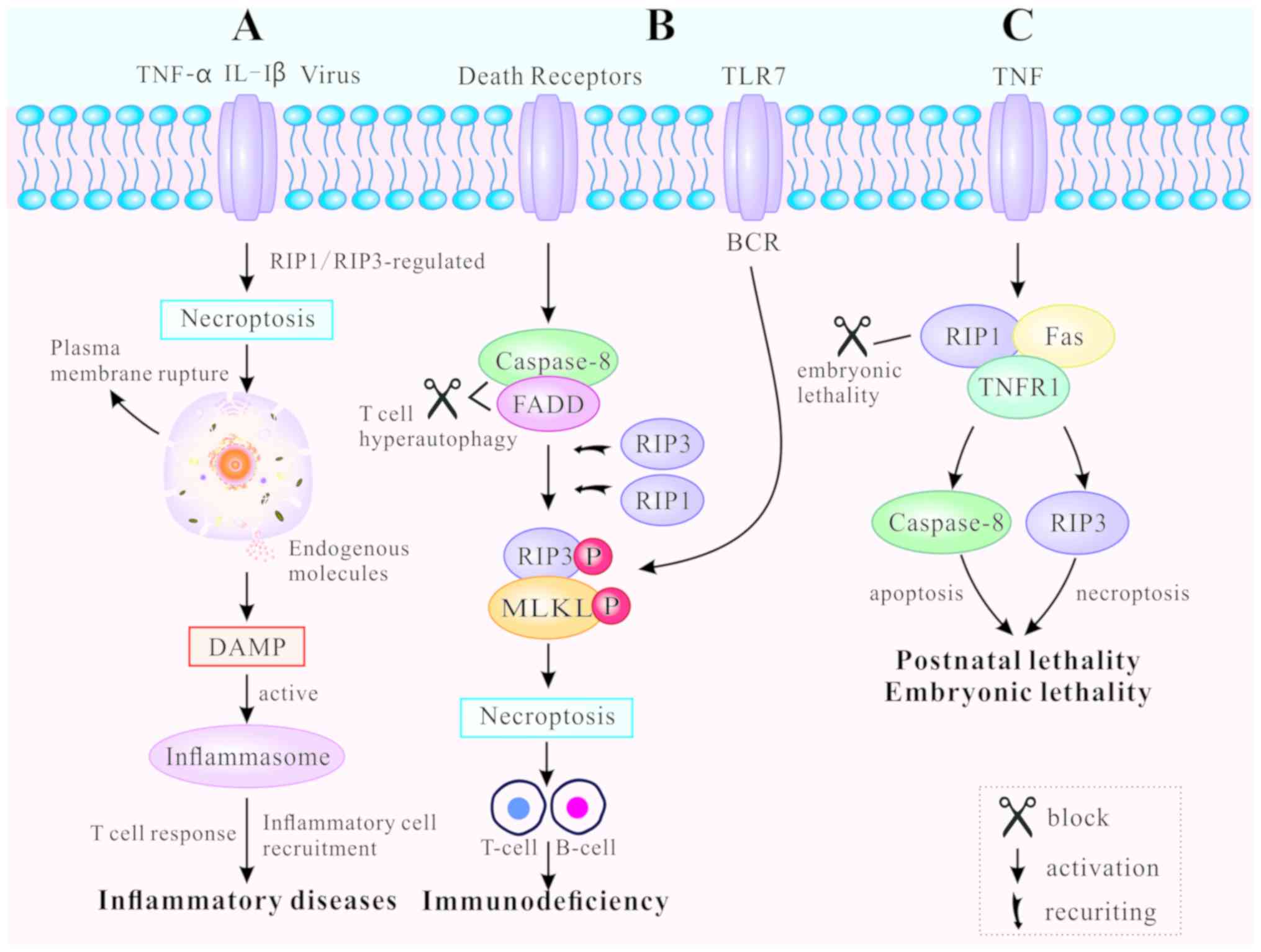

Necroptosis, as a novel pathway of PCD, leads to

release of endogenous moldecules from disrupted dying cells, that

subsequently triggers inflm-mation and immune response (67). Necroptosis-inducing factors

include TLR3 and TLR4 agonists [such as interleukin (IL)-1β)], TNF,

certain viral infections and T cell receptors (22). TNF-mediated and TLR-mediated

signaling pathways are the primary pathways for necroptosis, both

regulated by RIP3 (10).

RIP1/RIP3 or RIP3/TRIF signaling complexes recruit and

phosphorylate downstream MLKL, causing rupture of the plasma

membrane, as well as the release of endogenous molecules (45). These endogenous molecules are

known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). They are

also identified as part of the extended IL-1 family (IL-1α, IL-1β,

IL-18, IL-33, IL-36α, β and γ) (68). The leakage of DAMPs can activate

inflammasomes, facilitate inflammatory cell recruitment to the site

of infection, and promote subsequent virus-specific T cell

responses to induce inflammation (69). Thus, regulating the mechanism of

necroptosis can result in both inhibition and promotion of the

immune response (Fig. 4A).

DRs regulate necroptosis in various cell types, such

as B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes, both of which are essential for

immune homeostasis and tolerance (48,70). Blocked DRs fail to clear activated

lymphocytes and unbalanced lymphoid homeostasis, ultimately leading

to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) (71). FADD, caspase-8 and RIP kinases are

indispensable for T cell clonal expansion, contraction and

antiviral responses (48). When

caspase-8 and FADD are deficient, T cells undergo hyper-autophagy

and proliferative inhibition in response to antigenic stimulation.

In addition, T cells generate necrosomes, which induce

caspase-8-independent necroptosis (72). RIP1 and RIP3 are either recruited

by DRs or by other cellular signaling molecules, including DNA

damage and antigen receptor ligation (73). Chronic necroptosis may be the

basis of human fibrotic and autoimmune disorders (74). Likewise, B cell receptor (BCR)

mediates necroptosis via reaction with TLR7 to prevent autoimmune

diseases (75,76). The RIP1 inhibitor necrostatin-1

(nec-1) has been demonstrated to suppress B-cell necroptosis, when

pretreating B cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

(70). Fig. 4B illustrates how programmed death

can promote clonal loss of lymphocytes during infection and protect

patients against autoimmune disease.

Apoptosis and necroptosis are closely associated

with embryonic lethality and postnatal development (49). RIP1 determines cell survival or

death by associating with TNFR1, TLRs and Fas (17,77). Embryonic lethality of

RelA-deficient mice has been demonstrated to be mediated by

apoptosis and necroptosis (78).

FADD functions as an adaptor to induce apoptosis by recruiting and

activating caspase-8 (79). The

characteristics of FADD-deficient embryos are high levels of RIP1

production and massive necrosis. RIP1 ablation allows normal

embryo-genesis in FADD-deficient mice, but these mice usually die

around their first postnatal day (80). In addition, different RIP1 kinase

inactivating mutations have distinct effects on the embryogenesis

of FADD-deficient mice. For example, RIP1K45A has been found not to

prevent the embryonic lethality of FADD-deficient mice, while RIP1Δ

(with an altered P-loop in the kinase domain) does (81). If RIP1 was necessary for the

activation of RIP3, as aforementioned, FADD−/−

RIP1−/− and FADD −/− RIP3−/− mice

should survive to adulthood (82). Nevertheless, a recent study

revealed that RIP1-deficient mice die soon after birth, leading to

speculation for the positive role of RIP1 in embryonic development

and postnatal life (83). RIP1

deletion enhances primary cell sensitivity to

FADD/caspase-8-mediated apoptosis induced by TNF. In addition, RIP1

deletion promotes RIP3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis induced by TLR

ligation (via TRIF) or interferon (84). The perinatal lethality of

RIP1−/− mice can be rescued by a combination of

additional mutations. A recent study indicated that haploid

insufficiency of RIP3 improved the survival period of

RIP1−/− FADD−/− double knockout mice beyond

weaning age, while RIP1−/− FADD−/−

RIP3−/− triple knockout (TKO) mice were significantly

smaller in size and weight (85).

Furthermore, complete ablation of RIP3 further prolonged the life

span of TKO mice displaying normal size and weight (85). Therefore, it can be concluded that

RIP1 may prevent postnatal lethality by blocking two different cell

death pathways: FADD/caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and

RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis. The effect of PCD on animal

development is highly complex and has not yet been thoroughly

elucidated (Fig. 4C).

The increasing discovery of inhibitors and drugs

affecting the RIP1/RIP3 cascade pathway already shows promise

towards the treatment of various diseases (Table I). Nec-1 has been identified as a

specific and potent small-molecule and active inhibitor of RIP1

(2). Nec-1 is widely used in

disease models to examine the contribution of RIP1 to cell death

and inflammation. Other necrostatins, including Nec-3, Nec-4 and

Nec-5, also stabilize RIP1 in an inactive conformation through

interactions with hydrophobic pockets and highly conserved amino

acids (2,86). However, the strongest inhibition

of RIP1 has been observed with Nec-1 stable (Nec-1s) (87). A previous study identified

GSK2982772 (compound 5) as a novel inhibitor of RIP1 (88). GSK2982772 potently binds to RIP1

with exquisite kinase specificity and has high activity in blocking

TNF-dependent necroptosis, as well as inflammation. Based on this

previous study of GSK2982772, Yoshikawa et al (27) designed and synthesized a novel

class of RIP1 kinase inhibitor, the compound 22

[7-oxo-2,4,5,7-tetrahydro-6H-pyrazolo(3,4-c)pyridine], which

possesses moderate RIP1 kinase inhibitory activity and P-gp

mediated efflux. Furthermore, using a mouse model of systemic

inflammatory response syndrome, it was demonstrated that compound

56 (RIPA-56) targeted RIP1 directly, and reduced TNFα-induced cell

mortality and multi-organ damage (89). The pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor

Tozasertib (also known as VX-680 and MK-0457) was recently

demonstrated as a potent compound in inhibition of RIP1-dependent

necroptosis and in the blockage of cytokinesis in cells (90). The food and drug

administration-approved anticancer agents ponatinib and pazopanib

were demonstrated to be submicromolar inhibitors of necroptosis

through the targeting of components upstream of MLKL (91). Ponatinib inhibits both RIP1 and

RIP3, while pazopanib preferentially targets RIPK1. Both drugs have

potential values for the treatment of pathology caused or

aggravated by necroptotic cell death (91). Overall, the aforementioned studies

indicated that RIP1 kinase may serve as a novel target for

therapeutic drug development in human disease therapy.

RIP3 is a critical regulator of necroptosis,

however, very few specific inhibitors have yet been reported. B-Raf

(V600E) inhibitors are generally considered as an important

anticancer drug in metastatic melanoma therapy (92). To date, the B-Raf inhibitor

dabrafenib was demonstrated to be a potent inhibitor of RIP3

(92). Dabrafenib decreased

RIP3-mediated Ser358 phosphorylation of MLKL and disrupted the

interaction between RIP3 and MLKL (93). Results indicated that dabrafenib

could serve as a RIP3 inhibitor and as a potential preventive or

therapeutic agent for RIP3-involved necroptosis-related diseases

(93). As expected, dabrafenib

significantly reduced infarct lesion size and attenuated

upregulation of TNF-α in mouse models of ischemic brain injury

(94). In addition, murine

cytomegalovirus (CMV) M45 contains a RHIM domain, and was confirmed

to be a competitive inhibitor of RIP3 (95). Human CMV blocks TNF-induced

necroptosis following RIP3 activation and MLKL phosphorylation

(95), leading to inhibition of

the host defense mechanism.

As diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, miRNAs

provide a novel perspective for RIP1 inhibition. As aforementioned,

several inhibitors have been demonstrated to suppress the

pro-necroptosis function of RIP1 at the protein level; however,

these do not function at the mRNA level. miR-155 represses

cardiomyocyte progenitor cell necroptosis by targeting RIP1 rather

than activating the Akt pro-survival pathway (96), suggesting that miR-155 might be a

novel approach in improving cell engraftment. Additionally, in a

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion model, it was demonstrated that

miR-103/107, as a necrosis-suppressor miRNA, directly targeted FADD

(97,98). FADD participates in hydrogen

peroxide-induced necroptosis by influencing the formation of

RIP1/RIP3 complex, suggesting that FADD-targeting by miR-103/107

might be a new approach for preventing myocardial necrosis. Recent

research has indicated that miRNA dysregulation is involved in

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (100). Overexpression of miR-182

inhibits the CYLD action on the ubiquitin chains on RIP1, leading

to caspase-8-dependent apoptosis in TNF-α-treated TNBC cells

(99). Additionally, miR-145,

which is downregulated in TNBC, targeted cIAP1 and reduced the

formation of the RIP1/FADD-caspase-8 complex (100). Therefore, miRNAs can be

perceived as a novel approach for RIP1 regulation. However, their

potential effects in disease intervention requires further research

(Table II).

In TNFα-induced necroptosis, as RIP1 and RIP3 form a

protein complex through their common RHIM domain, phosphorylation

and activation of RIP3 and downstream MLKL occur (106). In addition, RHIM-containing

proteins, such as TLR, and interferon regulatory factors (Z-DNA

binding protein 1, also known as DAI or DLM1) are known to activate

RIP3 and further transduce necrosis signals to MLKL (107). TLR3 or TLR4 directly activate

necroptosis through the RHIM-dependent association of TRIF with

RIP3. This pathway proceeds independently of RIP1, but remains

dependent on MLKL downstream of RIP3 kinase (46). Dyngo 4a blocks the internalization

of TLR4 and prevents RIP3-induced necroptosis of macrophages

(108). A previous study

unveiled DAI as the RIP3 partner to interact with RIP3, mediating

virus-induced necrosis analogous to the RIP1/RIP3 complex

controlling TNF-induced necroptosis (109). Table I summarizes the direct and

indirect inhibitors of RIP3.

Necroptosis participates in the development of

several diseases, such as atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease, a

leading cause of mortality worldwide (110). Overexpression of RIP3 during

necroptosis of primary macrophages induced by oxidized LDL (ox-LDL)

facilitates the development of the disease (111). Furthermore, monoclonal

antibodies can be detected in the core of atherosclerotic plaques,

specifically recognizing the phosphorylation form of RIP3 at Ser232

(112). Notably, the mortality

of apolipoprotein E/RIP3 double-knockout mice was delayed

dramatically (112). These

findings indicated that RIP3-mediated necroptosis in

atherosclerotic plaques may release pro-inflammatory cytokines that

exacerbate atherosclerosis. Of note, PS-341, a potent and specific

proteasome inhibitor, was demonstrated to impair macrophage

necroptosis through stabilization of cIAPs and disruption of the

formation of the RIP1/RIP3 complex (113).

RIP1 inhibition leads to a reduction of infarct

size, implying a functional importance of necroptosis in myocardial

ischemia (MI) (114). Luedde

et al (20) analyzed RIP3

expression in murine hearts and highlighted the potential

functional significance of RIP3-dependent necroptosis in the

modulation of post-ischemic adverse remodeling in MI. A previous

study demonstrated that RIP3 was upregulated in murine hearts

subjected to ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury, as well as in

cardiomyocytes treated with LPS and hydrogen peroxide (115). This study further illustrated

that upregulated RIP3 evoked endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress,

ultimately resulting in cardiomyocyte necroptosis in the setting of

cardiac IR injury (115). In

addition, in a mouse cardiac hypertrophy model established by

transverse abdominal aortic constriction, both mRNA and protein

expression levels of RIP1 and RIP3 were increased significantly.

Losartan downregulated the expression of RIP1/RIP3, resulting in

the inhibition of necroptosis and to the alleviation of cardiac

hypertrophy (116). RIP1/RIP3

may thus be an attractive target for future therapies that aim to

limit the adverse consequences of cardiac disease.

The quaternary nitrogen herbicide paraquat is a

highly toxic pro-oxidant that triggers oxidative stress and

multi-organ failure, including that of the heart. Recently, Zhang

et al (117) revealed

that Nec-1 pretreatment prevented cardiac contractile dysfunction,

reduced RIP1/RIP3 interaction, downregulated the RIP1/RIP3/MLKL

signaling pathway, and dramatically inhibited the production of ROS

in paraquat-challenged mice. Thus, the RIP1/RIP3/MLKL signaling

cascade may represent an innovative therapeutic direction for

paraquat poisoning-induced cardiac contractile dysfunctions

(Table III).

Abundant research on RIP1/RIP3 has highlighted its

role in cancer, which is due to its necroptosis-inducing function

(118). Chen et al

(119) have noted that

necroptosis is a critical cell-killing mechanism in response to

severe stress and blocked apoptosis, and have proposed that it can

serve as an alternative cell death program to prevent cancer.

Previous studies have indicated that increased RIP3 expression was

correlated with cancer development, including colon and lung

cancers, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma

(120-122). The topoisomerase inhibitor SN38,

an active metabolite of irinotecan, was demonstrated to mediate

cytotoxicity through the TNF/TNFR signaling pathway in a panel of

colon cancer cells (123). SN38

also promoted the progression of necroptosis, inhibited cell

proliferation and induced DNA damage accumulation (123). This suggested that the

SN38-induced activation of RIP1 and subsequent necroptosis may

exert the therapeutic efficacy on colorectal carcinoma (123). Furthermore, Xin et al

(124) reported that degradation

of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1, a key negative regulator of

IFN-γ signaling, was prevented by TNF through RIP1/RIP3 signaling.

The authors suggested that necroptotic inhibition might be a novel

strategy for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia through the

combination of RIP1/RIP3 inhibitor with IFN-γ. Recently, bufalin

was demonstrated to increase the expression of necroptosis

mediators RIP1/RIP3 and ROS, leading to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

(PARP)-dependent tumor cell death and tumor growth inhibition in

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells (125). The promising role of

RIP1/RIP3-dependent necroptosis in cancer therapy warrants

attention in future studies (Table

III).

The death of hepatocytes initiates and aggravates

chronic inflammation and fibrosis during liver injury, ultimately

leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Increasing

evidence indicates that necroptosis has a key role in acute liver

injury and chronic liver injury (129). Deutsch et al (130) indicated that RIP1 and RIP3 have

different roles in drug-induced or immunological acute liver

injuries. In Concanavalin A (ConA)-induced autoimmune hepatitis,

RIP3 deletion delayed hepatic injury, while RIP1 inhibition

markedly exacerbated ConA-induced hepatitis (130). Conversely, in acetaminophen

(APAP)-mediated liver injury, blockade of RIP1 or RIP3 ameliorated

APAP toxicity (130). Zhang

et al (131) demonstrated

that RIP1 was strongly expressed and promoted acute liver failure

in mice treated with APAP (300 mg/kg, intraperitoneally injected).

Further analysis demonstrated that Nec-1, the inhibitor of RIP1,

significantly inhibited APAP-induced hepatic JNK phosphorylation

and mitochondrial Bax translocation (131). Using the APAP model in

RIP3−/− mice, Ramachandran et al (132) found that RIP3 knockout

significantly reduced hepatotoxicity after 6 h of APAP treatment

(200-300 mg/kg), while the protective effect of RIP3 knockout on

the liver was not obvious after 24 h of APAP treatment.

Chronic liver injury usually includes alcoholic

fatty liver disease (AELD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

(NAFLD), liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. It has been reported that

the expression of RIP3 in the liver tissue of patients with AFLD is

abnormally elevated, and a series of pathological changes, such as

hepatocyte lipid accumulation and elevated transaminase, are

observed in the liver (133,134). Additionally, Afonso et al

(135) reported that the

expression of RIP3 and phosphorylated MLKL was increased in the

liver tissue of patients with NAFLD, while RIP3 knockout

significantly reduced the steatosis and inflammatory response in

mice with methionine-choline diet. Choi et al (136) found that melatonin reduced the

expression of RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL in rat fibrotic liver induced by

CCl4, and inhibited the expression of high-mobility

group box 1 (HMGB1) and IL-1α. This suggested that melatonin can

alleviate liver fibrosis by inhibiting the inflammatory signaling

associated with programmed necrosis (136). Further studies are required to

fully elucidate the role of RIP1/RIP3-dependent necroptosis in

liver injury (Table III).

Increasing evidence has demonstrated that

necroptosis has an important role in the pathogenesis of multiple

types of kidney injury. Linkermann et al (137) first determined the presence of

necroptosis in a murine model of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury

(IRI). The detection of RIP1 and RIP3 in whole-kidney lysates and

freshly isolated murine proximal tubules revealed the contribution

of necroptosis in renal injury (137). A subsequent study demonstrated

that, in a mouse model of IRI, necroptosis lead to primary organ

damage, and RIP3-knockout mice were protected from IRI (138). Another study used MLKL-knockout

mice to investigate the role of necroptosis in acute kidney injury

(139). Their results revealed

the indispensable role of MLKL in the necroptotic pathway (139). Additionally, Xiao et al

(140) reported that the effect

of necroptosis and the RIP1/RIP3/MLKL signaling pathway in renal

inflammation and interstitial fibrosis was associated with

primitive tubulointerstitial injury. Inhibition of necroptosis

reduced the inflammatory response and interstitial fibrosis in

renal tissues (140). Therefore,

the signaling pathways and the main regulators of necroptosis may

serve as potential candidates for therapeutic strategies in kidney

injury (Table III).

Apoptosis was previously demonstrated to be a

significant form of cell loss in photoreceptor death, but

RIP-mediated necrosis was recently discovered to be a crucial mode

of photoreceptor cell loss in an experimental model of retinal

detachment (141). Expression of

RIP3 undergoes a 10-fold increase after retinal detachment

(142). Nevertheless, Nec-1 or

RIP3 deficiency substantially prevent necroptosis and reduce

oxidative stress of apoptosis-inducing factor (142). Additionally, cone photoreceptor

death in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is widely considered as a

necroptotic mechanism, while rod photoreceptor death is

characterized by apoptotic features (143). Murakami et al (144) reported that RIP3 expression was

elevated in rd10 mouse retinas in the cone phase, but not in rod

degeneration, and thus suggested that RIP3 may be a potential

target in protecting cone photoreceptors. On the other hand, Sato

et al (145) found that

RIP1/RIP3 accelerated both cone and rod photoreceptor degeneration

in interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (Irbp)−/−

mice. It is worth noting that Irbp deficiency displays severe early

and progressive photoreceptor degeneration. Based on these studies,

RIP1/RIP3 may be regarded as a potential therapeutic target to

prevent or delay photoreceptor degeneration in patients with

RP.

In an animal model of retinal detachment (RD),

cleaved IL-1β was reported in infiltrated macrophages undergoing

RIP3-dependent necroptosis, rather than dying photoreceptors

(146). In addition, Ito et

al (147) suggested a direct

connection between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis induced by

optineurin deficiency and RIP1-regulated necroptosis and

inflammation. Because it promotes both inflammation and cell death,

RIP1/RIP3 may be a common mediator of human degenerative diseases

characterized by axonal degeneration (Table III).

Donor organ injury is invariably mentioned in

transplantation, due to immune responses related to IRI and

alloimmune rejection (148). Lau

et al (149) reported

that in caspase-inhibited tubular epithelial cells (TECs),

necroptosis was triggered in vitro, following inhibition by

Nec-1 or RIP3−/− TEC. Following transplantation,

recipients receiving RIP3−/− kidneys had longer survival

and improved renal function (149). These results suggested that

inhibition of RIP3-dependent necroptosis and inflammatory injury in

donor organs may provide clinical benefit. Toxic epidermal

necrolysis (TEN) is a severe adverse drug reaction with a high

mortality rate (150). Kim et

al (151) detected upregulated expression of RIP3 and elevated

phosphorylation of MLKL in skin sections from patients with TEN.

Dabrafenib notably prevented RIP3-mediated MLKL phosphorylation and

decreased necroptosis, by inhibiting RIP3 in a TEN model (151).

Based on these findings, it can be speculated that RIP may

represent a potential target for treatment of TEN. Table III presents a list of existing

studies on the role of RIP1/RIP3-mediated necroptosis in

disease.

It is well-known that necroptosis, a

physiologically relevant form of cell death, is involved in

pathological cell death resulting from IRI. RIP1/RIP3 is a key

cascade involved in necroptosis, which is regulated by caspase

activation and ubiquitination. RIP1 regulates cell death and

survival, while RIP3 mediates apoptosis and necroptosis. Both TLR

and virus-mediated activation are recognized or identified by

specific receptors or sensors placed either inside or on the

surface of cells. RIP1/RIP3 mediates the initiation of the

necroptotic response to different stimuli. Following ligand binding

and receptor activation, RIP3 enters complex II via interaction

with RIP1, which then activates MLKL participation in inflammation,

immune response, embryonic development and metabolic

abnormality.

In conclusion, an improved understanding of the

molecular events regulating necroptotic cell death would be

extremely beneficial for disease therapy, as these mechanisms are

implicated in a variety of human illnesses. Further research in

this area can be expected to provide promising opportunities

regarding therapeutic exploitation of cell death programs. Due to

its crucial roles in organ growth and tumor cell proliferation,

RIP1/RIP3 may be a key potential therapeutic strategy in multiple

severe diseases. Therefore, by using small molecules that

specifically target necroptosis, it may be possible to alleviate

symptoms and prolong the lives of patients. In coming years,

further research on this alternative cell death pathway may include

identification of additional RIP1 and RIP3 substrates. RIP3 appears

to be the foremost promoter of necroptosis. In the future, studies

exploiting RIP3 inhibitors may provide crucial insight into the

diagnosis and treatment of necroptosis-associated diseases.

This study was sponsored by the National Science

Foundation of China (grant no 81802504), the Sichuan National

Science Research Funding (grant no. 2018JY0645), Sichuan Health and

Family Planning Commission Funding (grant no. 16ZD0253), Chengdu

National Science Research Funding (grant no. 2018-YFYF-00146-SN),

and funding from the Sichuan Scientific Research Grant for Returned

Overseas Chinese Scholars for Dr Yi Wang. This study was also

supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan of

China (grant no. 2017YFC0113901), the Key Research and Development

Plan of Sichuan Science and Technology Bureau (grant no.

2019YFS0278), the Health Care for government officials of Sichuan

Province and the Sichuan Health and Family Planning Commission

Funding (grant no. 120094) for Dr Yuping Liu.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the

present study are available from the corresponding author on

reasonable request.

YW, RT and YL conceived and designed the review.

DZ, TLiu, TLei, SD and LG wrote the manuscript. TLei, DQ and CL

prepared the figures. YW, RT and YL reviewed and edited the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, and

agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring

that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are

appropriately investigated and resolved.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

|

1

|

Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe

T and Kroemer G: Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: An ordered

cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11:700–714. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Jagtap P,

Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA and Yuan J:

Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic

potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 1:112–119.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Christofferson DE and Yuan J: Necroptosis

as an alternative form of programmed cell death. Curr Opin Cell

Biol. 22:263–268. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ashkenazi A and Salvesen G: Regulated cell

death: Signaling and mechanisms. Annu Rev Cell & Dev Biol.

30:337–356. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang YY and Liu H: Connections between

various trigger factors and the RIP1/RIP3 signaling pathway

involved in necroptosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 14:7069–7074.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mason AR, Elia LP and Finkbeiner S: The

receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)

regulates progranulin levels. J Biol Chem. 292:3262–3272. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Stanger BZ, Leder P, Lee TH, Kim E and

Seed B: RIP: A novel protein containing a death domain that

interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death.

Cell. 81:513–523. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sun X, Lee J, Navas T, Baldwin DT, Stewart

TA and Dixit VM: RIP3, a novel apoptosis-inducing kinase. J Biol

Chem. 274:16871–16875. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Newton K: RIPK1 and RIPK3: Critical

regulators of inflammation and cell death. Trends Cell Biol.

25:347–353. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray

TD, Guildford M and Chan FK: Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the

RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced

inflammation. Cell. 137:1112–1123. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB,

Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, Caspary T and

Mocarski ES: RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of

caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 471:368–372. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou W and Yuan J: Necroptosis in health

and diseases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 35:14–23. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe

F and Vanden Berghe T: The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in

TNF-induced necrosis. Sci Signal. 3:pp. re42010, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu XN, Yang ZH, Wang XK, Zhang Y, Wan H,

Song Y, Chen X, Shao J and Han J: Distinct roles of RIP1-RIP3

hetero- and RIP3-RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis.

Cell Death Differ. 21:1709–1720. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wen L, Zhuang L, Luo X and Wei P:

TL1A-induced NF-kappaB activation and c-IAP2 production prevent

DR3-mediated apoptosis in TF-1 cells. J Biol Chem. 278:39251–39258.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ahmad M, Srinivasula SM, Wang L, Talanian

RV, Litwack G, Fernandes-Alnemri T and Alnemri ES: CRADD, a novel

human apoptotic adaptor molecule for caspase-2, and FasL/tumor

necrosis factor receptor-interacting protein RIP. Cancer Res.

57:615–619. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Festjens N, Vanden BT, Cornelis S and

Vandenabeele P: RIP1, a kinase on the crossroads of a cell's

decision to live or die. Cell Death Differ. 14:400–410. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Newton K, Sun X and Dixit VM: Kinase RIP3

is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and

T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like

receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol. 24:1464–1469. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sun X, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, Fairbrother

WJ and Dixit VM: Identification of a novel homotypic interaction

motif required for the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting

protein (RIP) by RIP3. J Biol Chem. 277:9505–9511. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Luedde M, Lutz M, Carter N, Sosna J,

Jacoby C, Vucur M, Gautheron J, Roderburg C, Brg N, Reisinger F, et

al: RIP3, a kinase promoting necroptotic cell death, mediates

adverse remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res.

103:206–216. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Günther C, Neumann H, Neurath MF and

Becker C: Apoptosis, necrosis and necroptosis: Cell death

regulation in the intestinal epithelium. Gut. 62:1062–1071. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Pasparakis M and Vandenabeele P:

Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature. 517:311–320.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Magnusson C and Vaux DL: Signalling by

CD95 and TNF receptors: Not only life and death. Immunol Cell Biol.

77:41–46. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lan YH, Wu YC, Wu KW, Chung JG, Lu CC,

Chen YL, Wu TS and Yang JS: Death receptor 5-mediated TNFR family

signaling pathways modulate γ-humulene-induced apoptosis in human

colorectal cancer HT29 cells. Oncol Rep. 25:419–424. 2011.

|

|

25

|

Pan G, Bauer JH, Haridas V, Wang S, Liu D,

Yu G, Vincenz C, Aggarwal BB, Ni J and Dixit VM: Identification and

functional characterization of DR6, a novel death domain-containing

TNF receptor. FEBS Lett. 431:351–356. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Andera L: Signaling activated by the death

receptors of the TNFR family. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky

Olomouc Czech Repub. 153:173–180. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yoshikawa M, Saitoh M, Katoh T, Seki T,

Bigi SV, Shimizu Y, Ishii T, Okai T, Kuno M, Hattori H, et al:

Discovery of 7-Oxo-2,4,5,7-tetrahydro-6 H-pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridine

derivatives as potent, orally available, and brain-penetrating

receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) kinase inhibitors: Analysis

of structure-kinetic relationships. J Med Chem. 61:2384–2409. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Vanlangenakker N, Bertrand MJM, Bogaert P,

Vandenabeele P and Berghe TV: TNF-induced necroptosis in L929 cells

is tightly regulated by multiple TNFR1 complex I and II members.

Cell Death Dis. 2:pp. e2302011, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Micheau O and Tschopp J: Induction of TNF

receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling

complexes. Cell. 114:181–190. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wong WW, Gentle IE, Nachbur U, Anderton H,

Vaux DL and Silke J: RIPK1 is not essential for TNFR1-induced

activation of NF-kappaB. Cell Death Differ. 17:482–487. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Mack C, Sickmann A, Lembo D and Brune W:

Inhibition of proinflammatory and innate immune signaling pathways

by a cytomegalovirus RIP1-interacting protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 105:3094–3099. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang L, Du F and Wang X: TNF-alpha induces

two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 133:693–703.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Benetatos CA, Mitsuuchi Y, Burns JM,

Neiman EM, Condon SM, Yu G, Seipel ME, Kapor GS, Laporte MG, Rippin

SR, et al: Birinapant (TL32711), a bivalent SMAC mimetic, targets

TRAF2-associated cIAPs, abrogates TNF-induced NF-κB activation, and

is active in patient-derived xenograft models. Mol Can Ther.

13:867–879. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hughes MA, Powley IR, Jukesjones R, Horn

S, Feoktistova M, Fairall L, Schwabe JW, Leverkus M, Cain K,

MacFarlane M, et al: Co-operative and hierarchical binding of

c-FLIP and caspase-8: A unified model defines how c-FLIP isoforms

differentially control cell fate. Mol Cell. 61:834–849. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick

LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, Hakem R, Salvesen GS and Green DR:

Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIPL complex inhibits

RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 471:363–367. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ikner A and Ashkenazi A: TWEAK induces

apoptosis through a death-signaling complex comprising

receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), Fas-associated death domain

(FADD), and caspase-8. J Biol Chem. 286:21546–21554. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y and Liu Z:

Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by Caspase-8 p rompts

TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 13:2514–2526. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vanden BT, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S,

Walczak H and Vandenabeele P: Regulated necrosis: The expanding

network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 15:135–147. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Li J, Mcquade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J,

Moriwaki K, Hsiao YS, Damko E, Moquin D, Walz T, McDermott A, et

al: The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling

complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 150:339–350. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

He S, Wang L, Miao L, Wang T, Du F, Zhao L

and Wang X: Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines

cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 137:1100–1111. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang Y, Su SS, Zhao S, Yang Z, Zhong CQ,

Chen X, Cai Q, Yang ZH, Huang D, Wu R and Han J: RIP1

autophosphorylation is promoted by mitochondrial ROS and is

essential for RIP3 recruitment into necrosome. Nat Commun.

8:143292017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Moquin DM, Mcquade T and Chan FK: CYLD

deubiquitinates RIP1 in the TNFα-induced necrosome to facilitate

kinase activation and programmed necrosis. PLoS One. 8:pp.

e768412013, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao

D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X and Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase

domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3

kinase. Cell. 148:213–227. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dondelinger Y, Declercq W, Montessuit S,

Roelandt R, Goncalves A, Bruggeman I, Hulpiau P, Weber K, Sehon CA

and Marquis RW: MLKL compromises plasma membrane integrity by

binding to phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Cell Rep. 7:971–981.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang

LF, Wang FS and Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein

MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by

RIP3. Mol Cell. 54:133–146. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kaiser WJ, Sridharan H, Huang C, Mandal P,

Upton JW, Gough PJ, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Bertin J and Mocarski ES:

Toll-like receptor 3-mediated necrosis via TRIF, RIP3, and MLKL. J

Biol Chem. 288:31268–31279. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

He S, Liang Y, Shao F and Wang X:

Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages

through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 108:20054–20059. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lu J: Regulation of necroptosis and

autophagy in T cell homeostasis and function. University of

California; Irvine: 2014

|

|

49

|

Walsh CM: Grand challenges in cell death

and survival: Apoptosis vs. necroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

2:32014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H,

Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K and Akira S: Cutting edge: Toll-like

receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to

lipopolysaccharide: Evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J

Immunol. 162:3749–3752. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Takaki H, Shime H, Matsumoto M and Seya T:

Tumor cell death by pattern-sensing of exogenous RNA: Tumor cell

TLR3 directly induces necroptosis by poly(I:C) in vivo, independent

of immune effector-mediated tumor shrinkage. Oncoimmunology. 6:pp.

e10789682015, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K,

Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okab M, Takeda K and

Akira S: Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like

receptor signaling pathway. Science. 301:640–643. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K and

Akira S: Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin.

Immunity. 11:115–122. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, Janssen E,

Tabeta K, Kim SO, Goode J, Lin P, Mann N and Mudd S: Identification

of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling.

Nature. 424:743–748. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M,

Attinger A, Valitutti S, Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Seed B and Tschopp

J: Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death

pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nature Immunol.

1:489–495. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Geserick P, Hupe M, Moulin M, Wong WW,

Feoktistova M, Kellert B, Gollnick H, Silke J and Leverkus M:

Cellular IAPs inhibit a cryptic CD95-induced cell death by limiting

RIP1 kinase recruitment. J Cell Biol. 187:1037–1054. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Robinson N, Mccomb S, Mulligan R, Dudani

R, Krishnan L and Sad S: Type I interferon induces necroptosis in

macrophages during infection with salmonella enterica serovar

typhimurium. Nature Immunol. 13:954–962. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Kaiser WJ, Upton JW and Mocarski ES: Viral

modulation of programmed necrosis. Curr Opin Virol. 3:296–306.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhang Y, Chen X, Gueydan C and Han J:

Plasma membrane changes during programmed cell deaths. Cell Res.

28:9–21. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

60

|

Orozco S, Yatim N, Werner MR, Tran H,

Gunja SY, Tait SW, Albert ML, Green DR and Oberst A: RIPK1 both

positively and negatively regulates RIPK3 oligomerization and

necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 21:1511–1521. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wajant H and Scheurich P: TNFR1-induced

activation of the classical NF-κB pathway. FEBS J. 278:862–876.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Jaco I, Annibaldi A, Lalaoui N, Wilson R,

Tenev T, Laurien L, Kim C, Jamal K, Wicky John S, Liccardi G, et

al: MK2 phosphorylates RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced cell death. Mol

Cell. 66:698–710.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Kearney CJ, Cullen SP, Danielle C and

Martin SJ: RIPK1 can function as an inhibitor rather than an

initiator of RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. FEBS J. 281:4921–4934.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Schenk B and Fulda S: Reactive oxygen

species regulate Smac mimetic/TNFα-induced necroptotic signaling

and cell death. Oncogene. 34:5796–5806. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhang DW, Shao J, Lin J, Zhang N, Lu BJ,

Lin SC, Dong MQ and Han J: RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator

that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis.

Science. 325:332–336. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Wen S, Wu X, Gao H, Yu J, Zhao W, Lu JJ,

Wang J, Du G and Chen X: Cytosolic calcium mediates RIP1/RIP3

complex-dependent necroptosis through JNK activation and

mitochondrial ROS production in human colon cancer cells. Free

Radic Biol Med. 108:433–444. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Kearney CJ and Martin SJ: An inflammatory

perspective on necroptosis. Mol Cell. 65:965–973. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Martin SJ: Cell death and inflammation:

The case for IL-1 family cytokines as the canonical DAMPs of the

immune system. FEBS J. 283:2599–2615. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Kono H and Rock KL: How dying cells alert

the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 8:279–289. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Fan H, Liu F, Dong G, Ren D, Xu Y, Dou J,

Wang T, Sun L and Hou Y: Activation-induced necroptosis contributes

to B-cell lymphopenia in active systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell

Death Dis. 5:pp. e14162014, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Siegel RM: Caspases at the crossroads of

immune-cell life and death. Nat Rev Immunol. 6:308–317. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Bell BD, Leverrier S, Weist BM, Newton RH,

Arechiga AF, Luhrs KA, Morrissette NS and Walsh CM: FADD and

caspase-8 control the outcome of autophagic signaling in

proliferating T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:16677–16682.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Lu JV and Walsh CM: Programmed necrosis

and autophagy in immune function. Immunol Rev. 249:205–217. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

O'Donnell JA, Lehman J, Roderick JE,

Martinez-Marin D, Zelic M, Doran C, Hermance N, Lyle S, Pasparakis

M, Fitzgerald KA, et al: Dendritic cell RIPK1 maintains immune

homeostasis by preventing inflammation and autoimmunity. J Immunol.

200:737–748. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

75

|

Giltiay NV, Chappell CP, Sun X, Kolhatkar

N, Teal TH, Wiedeman AE, Kim J, Tanaka L, Buechler MB, Hamerman JA,

et al: Overexpression of TLR7 promotes cell-intrinsic expansion and

autoantibody production by transitional T1B cells. J Exp Med.

210:2773–2789. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Mina-Osorio P, LaStant J, Keirstead N,

Whittard T, Ayala J, Stefanova S, Garrido R, Dimaano N, Hilton H,

Giron M, et al: Suppression of glomerulonephritis in lupus-prone

NZB x NZW mice by RN486, a selective inhibitor of Bruton's tyrosine

kinase. Arthritis Rheum. 65:2380–2391. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Biton S and Ashkenazi A: NEMO and RIP1

control cell fate in response to extensive DNA damage via TNF-α

feedforward signaling. Cell. 145:92–103. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Xu C, Wu X, Zhang X, Xie Q, Fan C and

Zhang H: Embryonic lethality and host immunity of relA-deficient

mice are mediated by both apoptosis and necroptosis. J Immunol.

200:271–285. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Lu JV, Weist BM, van Raam BJ, Marro BS,

Nguyen LV, Srinivas P, Bell BD, Luhrs KA, Lane TE, Salvesen GS and

Walsh CM: Complementary roles of fas-associated death domain (FADD)

and receptor interacting protein kinase-3 (RIPK3) in T-cell

homeostasis and antiviral immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:15312–15317. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Zhang H, Zhou X, Mcquade T, Li J, Chan FK

and Zhang J: Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in

embryos and lymphocytes. Nature. 471:373–376. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Liu Y, Fan C, Zhang Y, Yu X, Wu X, Zhang

X, Zhao Q, Zhang H, Xie Q, Li M, et al: RIP1 kinase

activity-dependent roles in embryonic development of fadd-deficient

mice. Cell Death Differ. 24:1459–1469. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Dillon CP, Oberst A, Weinlich R, Janke LJ,

Kang TB, Ben-Moshe T, Mak TW, Wallach D and Green DR: Survival

function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Rep.

1:401–407. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Kaiser WJ, Daleybauer LP, Thapa RJ, Mandal

P, Berger SB, Huang C, Sundararajan A, Guo H, Roback L, Speck SH,

et al: RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic

cell death during mammalian parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:7753–7758. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Rodriguez DA,

Cripps JG, Quarato G, Gurung P, Verbist KC, Brewer TL, Llambi F,

Gong YN, et al: RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by

caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 157:1189–1202. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Dowling JP, Nair A and Zhang J: A novel

function of RIP1 in postnatal development and immune homeostasis by

protecting against RIP3-dependent necroptosis and FADD-mediated

apoptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 3:122015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch'en

IL, Korkina O, Teng X, Abbott D, Cuny GD, Yuan C, Wagner G, et al:

Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of

necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 4:313–321. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Takahashi N, Duprez L, Grootjans S,

Cauwels A, Nerinckx W, DuHadaway JB, Goossens V, Roelandt R, Van

Hauwermeiren F, Libert C, et al: Necrostatin-1 analogues: Critical

issues on the specificity, activity andin vivouse in experimental

disease models. Cell Death Dis. 3:pp. e4372012, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Harris PA, Berger SB, Jeong JU, Nagilla R,

Bandyopadhyay D, Campobasso N, Capriotti CA, Cox JA, Dare L, Dong

X, et al: Discovery of a first-in-class receptor interacting

protein 1 (RIP1) kinase specific clinical candidate (GSK2982772)

for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. J Med Chem.

60:1247–1261. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Ren Y, Su Y, Sun L, He S, Meng L, Liao D,

Liu X, Ma Y, Liu C, Li S, et al: Discovery of a highly potent,

selective, and metabolically stable inhibitor of

receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) for the treatment of systemic

inflammatory response syndrome. J Med Chem. 60:972–986. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Martens S, Goossens V, Devisscher L,

Hofmans S, Claeys P, Vuylsteke M, Takahashi N, Augustyns K and

Vandenabeele P: RIPK1-dependent cell death: A novel target of the

Aurora kinase inhibitor Tozasertib (VX-680). Cell Death Dis.

9:2112018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Fauster A, Rebsamen M, Huber KVM,

Bigenzahn JW, Stukalov A, Lardeau CH, Scorzoni S, Bruckner M,

Gridling M, Parapatics K, et al: A cellular screen identifies

ponatinib and pazopanib as inhibitors of necroptosis. Cell Death

Dis. 6:pp. e17672015, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Alcalá AM and Flaherty KT: BRAF inhibitors

for the treatment of metastatic melanoma: Clinical trials and

mechanisms of resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 18:33–39. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Li JX, Feng JM, Wang Y, Li XH, Chen XX, Su

Y, Shen YY, Chen Y, Xiong B, Yang CH, et al: The B-RafV600E

inhibitor dabrafenib selectivelyinhibits RIP3 and alleviates

acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 5:pp.

e12782014, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Cruz SA, Qin Z, Afr S and Chen HH:

Dabrafenib, an inhibitor of RIP3 kinase-dependent necroptosis,

reduces ischemic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. 13:252–256. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Omoto S, Guo H, Talekar GR, Roback L,

Kaiser WJ and Mocarski ES: Suppression of RIP3-dependent

necroptosis by human cytomegalovirus. J Biol Chem. 290:11635–11648.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Liu J, Mil AV, Vrijsen K, Zhao J, Gao L,

Metz CH, Goumans MJ, Doevendans PA and Sluijter JP: MicroRNA-155

prevents necrotic cell death in human cardiomyocyte progenitor

cells via targeting RIP1. J Cell Mol Med. 15:1474–1482. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Dhingra R, Lin J and Kirshenbaum LA:

Disruption of RIP1-FADD complexes by microRNA-103/107 provokes

necrotic cardiac cell death. Circ Res. 117:314–316. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Wang JX, Zhang XJ, Li Q, Wang K, Wang Y,

Jiao JQ, Feng C, Teng S, Zhou LY, Gong Y, et al: MicroRNA-103/107

regulate programmed necrosis and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury through targeting FADD. Circ Res. 117:352–363. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Wo L, Lu D and Gu X: Knockdown of miR-182

promotes apoptosis via regulating RIP1 deubiquitination in

TNF-α-treated triple-negative breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol.

37:13733–13742. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zheng M, Wu Z, Wu A, Huang Z, He N and Xie

X: MiR-145 promotes TNF-α-induced apoptosis by facilitating the

formation of RIP1-FADDcaspase-8 complex in triple-negative breast

cancer. Tumor Biol. 37:8599–8607. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Li D, Xu T, Cao Y, Wang H, Li L, Chen S,

Wang X and Shen Z: A cytosolic heat shock protein 90 and

cochaperone CDC37 complex is required for RIP3 activation during

necroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:5017–5022. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Li D, Li C, Li L, Chen S, Wang L, Li Q,

Wang X, Lei X and Shen Z: Natural product kongensin a is a

non-canonical HSP90 inhibitor that blocks RIP3-dependent

necroptosis. Cell Chem Biol. 23:257–266. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Jacobsen AV, Lowes KN, Tanzer MC, Lucet

IS, Hildebrand JM, Petrie EJ, van Delft MF, Liu Z, Conos SA, Zhang

JG, et al: HSP90 activity is required for MLKL oligomerisation and

membrane translocation and the induction of necroptotic cell death.

Cell Death Dis. 7:pp. e20512016, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhao XM, Chen Z, Zhao JB, Zhang PP, Pu YF,

Jiang SH, Hou JJ, Cui YM, Jia XL and Zhang SQ: Hsp90 modulates the

stability of MLKL and is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Cell

Death Dis. 7:pp. e20892016, View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Park SY, Shim JH, Chae JI and Cho YS: Heat

shock protein 90 inhibitor regulates necroptotic cell death via

down-regulation of receptor interacting proteins. Pharmazie.

70:193–198. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Declercq W, Vanden BT and Vandenabeele P:

RIP kinases at the crossroads of cell death and survival. Cell.

138:229–232. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Chan FK, Luz NF and Moriwaki K: Programmed

necrosis in the cross talk of cell death and inflammation. Annu Rev

Immunol. 33:79–106. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

108

|

Ariana A: Dissection of TLR4-Induced

Necroptosis Using Specific Inhibitors of Endocytosis and P38 MAPK.

Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology University

of Ottawa; Ottawa, Canada: 2017

|

|

109

|

Upton JW, Kaiser WJ and Mocarski ES: DAI

complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis

that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe.

11:290–297. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Gupta K, Phan N, Wang Q and Liu B:

Necroptosis in cardiovascular disease-a new therapeutic target. J

Mol Cell Cardiol. 118:26–35. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Lin J, Li H, Yang M, Ren J, Huang Z, Han

F, Huang J, Ma J, Zhang D, Zhang Z, et al: A role of RIP3-mediated

macrophage necrosis in atherosclerosis development. Cell Rep.

3:200–210. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Meng L, Jin W and Wang X: RIP3-mediated

necrotic cell death accelerates systematic inflammation and

mortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:11007–11012. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Zhang Y, Cheng J, Zhang J, Wu X, Chen F,

Ren X, Wang Y, Li Q and Li Y: Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 limits

macrophage necroptosis by promoting cIAPs-mediated inhibition of

RIP1 and RIP3 activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 477:761–767.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Oerlemans MI, Liu J, Arslan F, den Ouden

K, van Middelaar BJ, Doevendans PA and Sluijter JP: Inhibition of

RIP1-dependent necrosis prevents adverse cardiac remodeling after

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. Basic Res Cardiol.

107:2702012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Zhu P, Hu S, Jin Q, Li D, Tian F, Toan S,

Li Y, Zhou H and Chen Y: Ripk3 promotes ER stress-induced

necroptosis in cardiac IR injury: A mechanism involving calcium

overload/XO/ROS/mPTP pathway. Redox Biol. 16:157–168. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Zhao M, Qin Y, Lu L, Tang X, Wu W, Fu H

and Liu X: Preliminary study of necroptosis in cardiac hypertrophy

induced by pressure overload. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za

Zhi. 32:618–623. 2015.In Chinese. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Zhang L, Feng Q and Wang T: Necrostatin-1

protects against paraquat-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction

via RIP1-RIP3-MLKL-dependent necroptosis pathway. Cardiovasc

Toxicol. 18:346–355. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Meng MB, Wang HH, Cui YL, Wu ZQ, Shi YY,

Zaorsky NG, Deng L, Yuan ZY, Lu Y and Wang P: Necroptosis in

tumori-genesis, activation of anti-tumor immunity, and cancer

therapy. Oncotarget. 7:57391–57413. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Chen D, Yu J and Zhang L: Necroptosis: An

alternative cell death program defending against cancer. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1865:228–236. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Yang Y, Hu W, Feng S, Ma J and Wu M: RIP3

beta and RIP3 gamma, two novel splice variants of

receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3), downregulate RIP3-induced

apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 332:181–187. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Kasof GM, Prosser JC, Liu D, Lorenzi MV

and Gomes BC: The RIP-like kinase, RIP3, induces apoptosis and

NF-kappaB nuclear translocation and localizes to mitochondria. FEBS

Lett. 473:285–291. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Wu W, Liu P and Li J: Necroptosis: An

emerging form of programmed cell death. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

82:249–258. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Cabal-Hierro L and O'Dwyer PJ: TNF

signaling through RIP1 kinase enhances SN38-induced death in colon

adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 15:395–404. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Xin J, You D, Breslin P, Li J, Zhang J,

Wei W, Cannova J, Volk A, Gutierrez R, Xiao Y, et al: Sensitizing

acute myeloid leukemia cells to induced differentiation by

inhibiting the RIP1/RIP3 pathway. Leukemia. 124:1154–1165. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Li Y, Liu X, Gong P and Tian X: Bufalin

inhibits human breast cancer tumorigenesis by inducing cell death

through the ROS-Mediated RIP1/RIP3/PARP-1 pathways. Carcinogenesis.

39:700–707. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Larocca TJ, Sosunov SA, Shakerley NL, Ten

VS and Ratner AJ: Hyperglycemic conditions prime cells for

RIP1-dependent necroptosis. J Biol Chem. 291:13753–13761. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Mccaig WD, Patel PS, Sosunov SA, Shakerley

NL, Smiraglia TA, Craft MM, Walker KM, Deragon MA, Ten VS and

LaRocca TJ: Hyperglycemia potentiates a shift from apoptosis to

RIP1-dependent necroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 4:552018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Wang K, Hu L and Chen JK: RIP3-deficience

attenuates potassium oxonate-induced hyperuricemia and kidney

injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 101:617–626. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Dara L, Liu ZX and Kaplowitz N: Questions

and controversies: The role of necroptosis in liver disease. Cell

Death Discov. 2:160892016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Deutsch M, Graffeo CS, Rokosh R, Pansari

M, Ochi A, Levie EM, Van Heerden E, Tippens DM, Tippens DM, Greco

S, et al: Divergent effects of RIP1 or RIP3 blockade in murine

models of acute liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 6:pp. e17592015,

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Zhang YF, He W, Zhang C, Liu XJ, Lu Y,