Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme is the most common primary

brain tumor in humans arising from cells of the glia lineage. The

name denotes a very heterogeneous type of tumor with respect to

cell morphology and chromosome aberrations, which includes extended

deletions, gain of entire chromosomes or chromosome arms and gene

amplification (1). Surgical

resection and radiotherapy are the first and second stage of

treatment of glioblastoma, respectively, while the addition of

chemotherapy to radiation has so far shown limited improved

survival (2,3). In mammals, exposure of cells to

radiation causes DNA double-strand breaks that are generally

repaired via non-homologous end joining following activation of

DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) (4). However, when DNA damage is excessive,

cells induce DNA-PK-mediated apoptosis. It has been reported that

exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation leads to autophagy

induction in some types of cancer cells including malignant glioma

cells (5).

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy)

is a biphasic process characterized by the formation of

double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes (i.e. the formation

phase) often containing subcellular organelles, which fuse with

lysosomes. In the following maturation phase the vesicle content is

degraded generating macromolecules and ATP that are recycled as to

maintain cellular homeostasis (6).

The formation of autophagosomes is mediated by a highly organized

and hierarchical team of autophagy-related gene products (ATG

proteins) of which microtubule-associated protein light chain 3

(LC3), the mammalian homolog of yeast ATG8p, is the most specific

marker as it accumulates on the autophagosomal membrane giving rise

to characteristic punctate patterns (6,7).

Several recent studies have suggested that autophagy also functions

as a pro-death mechanism. In this respect, it has been shown that

different types of cancer cells undergo autophagic cell death in

response to anticancer therapy (8,9). At

present, it remains controversial whether autophagy represents a

survival and cytoprotective process or causes death in cancer cells

as well as the precise molecular mechanisms that regulate this

dynamic process.

Recent studies from our laboratory have revealed

that siRNA-mediated downregulation of protein kinase CK2 leads to

morphological changes resembling activation of autophagic cells

death in human glioblastoma cells (10). Protein kinase CK2 is a

constitutively active and highly conserved serine/threonine kinase

composed of two catalytic α and/or α′ subunits and two regulatory β

subunits. Evidence indicates that the individual subunits do not

exist exclusively within the tetrameric complex but also as free

proteins (11,12). CK2 expression and activity are

deregulated in many human diseases including cancer and while the

overexpression often correlates with enhanced cell survival and

proliferation, cellular depletion generally results in reduced cell

viability and increased cell death, particularly apoptosis

(13). Moreover, although mounting

evidence underlines the importance of targeting CK2 for activation

of apoptosis in cancer cells, the role of this kinase with respect

to induction and/or progression of other types of cell death such

as autophagy is largely unknown.

In this study, we aimed to shed light on the

mechanism by which CK2 silencing induces autophagy in human

glioblastoma cells treated with the radiomimetic drug

neocarzinostatin. We report evidence that downregulation of protein

kinase CK2 results in inhibition of the mammalian target of

rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, downregulation of Raptor expression

levels and activation of the extracellular signaling-regulated

protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling pathway as evidenced by ERK

phosphorylation and enhanced kinase activity. The reported results

support the notion that CK2 may serve as a potential target for

enhancing the cellular response of glioblastoma cells resistant to

multiple drug treatments.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human glioblastoma cell lines M059K and T98G

were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville,

MD, USA). The cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Taastrup,

Denmark) with 10% FBS and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2

atmosphere.

Cell culture and treatments

Cells were transfected with a set of 4 small

interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes directed against CK2α or CK2α′

(On-Target plus SMARTpools, Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA), using

Dharmafect I transfection reagent (Dharmacon) for 72 h according to

the manufacturer’s instructions. Control experiments were performed

transfecting cells with scramble siRNA sequences. Where indicated,

cells were incubated with the radiomimetic drug neocarzinostatin

for 24 h (NCS, a gift from Dr Hiroshi Maeda, Kumamoto University,

Kumamoto, Japan). Endogenous mTOR activity was inhibited by

incubating T98G cells with 100 nM rapamycin (Calbiochem,

Nottingham, UK) and M059K cells with 50 nM rapamycin, respectively.

Maturation of autophagy vacuoles was inhibited by treating cells

with 50 nM bafilomycin A (Calbiochem) for 6 h prior to cell

analysis.

Flow cytometry

Autophagy was analyzed by staining cells with the

vital dye acridine orange (Sigma, Brondby, Denmark). Briefly, cells

were incubated with acridine orange at a final concentration of 1

μg/ml for 15 min prior to trypsinization and flow cytometry

analysis on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA)

using CellQuest Pro Analysis Software (BD Biosciences). To detect

mitochondrial superoxide production, cells were trypsinized and

incubated with 5 μM MitoSOX™ Red Mitochondrial Superoxide

indicator (Invitrogen) for 15 min prior to FACS analysis. ROS

scavengers treatment was performed by incubating cells with 100

μM BHA or 50 μM BPN (both from Sigma) for 24 h prior

to harvesting and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell extracts and immunoblotting were as

previously described (14). The

primary antibodies employed in this study were: mouse monoclonal

anti-CK2β and -CK2α (both from Calbiochem); rabbit polyclonal

anti-CK2α′ obtained by immunizing rabbits with a specific peptide

(SQPCADNAVLSSGTAAR) deriving from human CK2α′; mouse monoclonal

anti-β-actin (Sigma); mouse monoclonal anti-mTOR and -AKT1 (both

from BD Biosciences), rabbit monoclonal anti-Raptor and -ERK1/2

(p-T202/Y204); rabbit polyclonal anti-mTOR (p-S2481) and -ERK1/2

(all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); mouse

monoclonal anti-AKT (p-S473) and -p70 S6 kinase (p-T389) (both from

Cell Signaling Technology) and rabbit polyclonal anti-p70 S6 kinase

(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Protein bands were

then visualized by a chemiluminescence detection system following

the manufacturer’s guidelines (CDP-Star; Applied Biosystems, Foster

City, CA, USA).

In vitro protein kinase assay

The activity of ERK1/2 was tested using a

non-radioactive p44/42 MAPK kinase assay kit (Cell Signaling

Technology) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly,

whole cells extracts were immunoprecipitated with rabbit monoclonal

anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody

immobilized on sepharose beads. Immunoprecipitates were subjected

to a non-radioactive kinase assay in the presence of 0.25 μg

recombinant GST-fused Elk-1, 1X kinase buffer-containing 200

μM ATP. Incubation time was 30 min at 30°C. Phosphorylation

of Elk-1 was revealed by labeling western blot membranes with mouse

monoclonal anti-phospho-Elk-1 (Ser383) antibody.

EGFP-LC3 translocation assay

Cells were grown on cover-slips and transfected with

CK2-siRNA for 48 h, prior to addition of NCS for 24 h. To visualize

GFP-LC3, cells were infected with Premo Autophagy Sensors (LC3B-FP,

wild-type) BacMam2.0 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. The LC3B (G120A)-FP mutant form was employed in

control experiments, as the mutation of the expressed LC3B prevents

its cleavage and subsequent lipidation following induction of

autophagy. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Na-citrate/0.2% Triton X-100

for 5 min and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

(DAPI) and analyzed on a DMRBE microscope (×400 magnification)

equipped with a Leica DFC420C camera. Pictures were processed using

ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). For each condition, at

least 200 GFP-LC3-expressing cells were analyzed and the percentage

of puncta per cell, deriving from the expression of GFP, was

determined by using the ‘analyze particles’ function in the ImageJ

software.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between

the means of two groups was evaluated by the two-tailed t-test and

the level of significance was as indicated in the figure

legends.

Results

Downregulation of protein kinase CK2

induces autophagic cell death in human glioblastoma cells

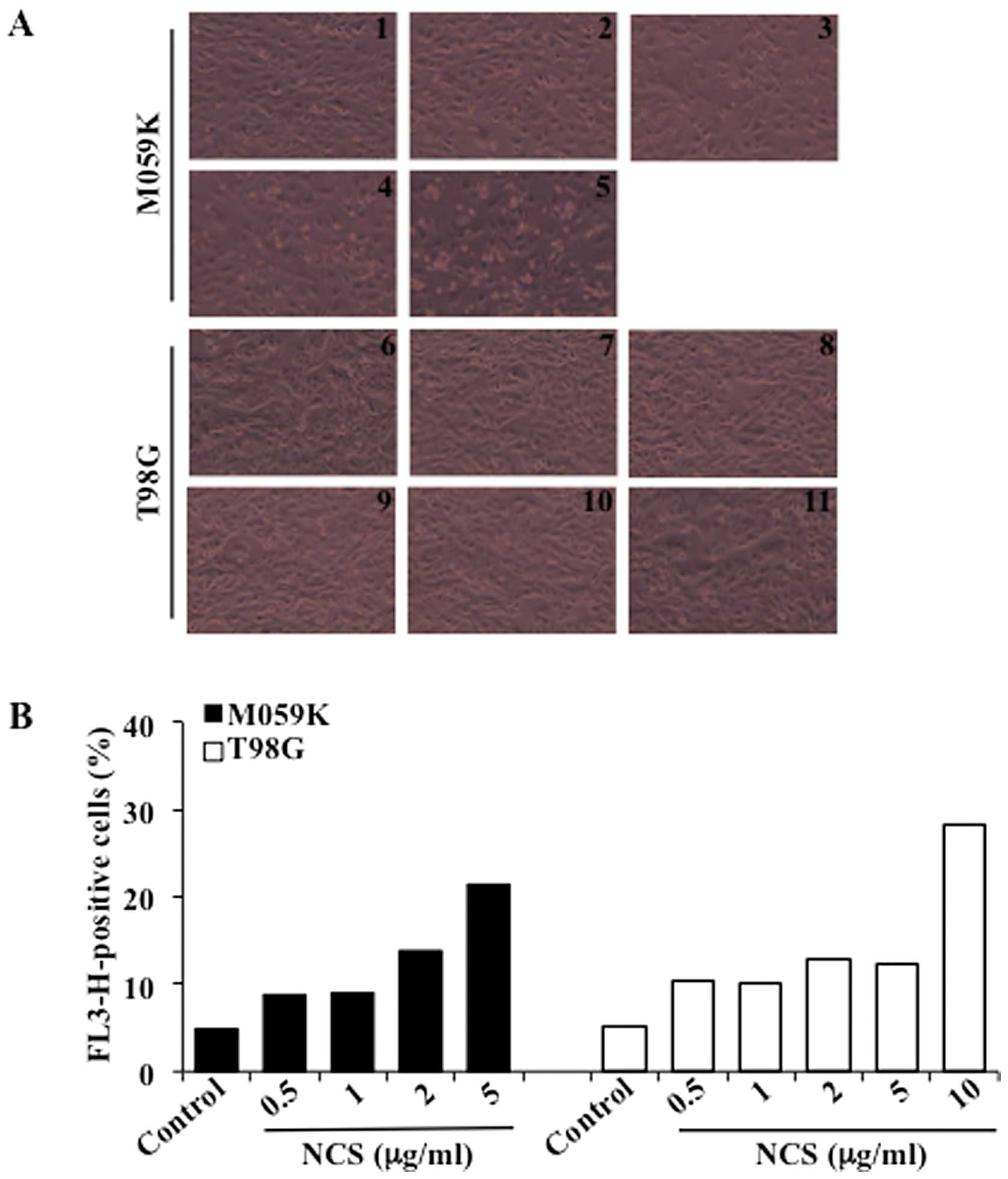

Accumulating evidence indicates that induction of

DNA double-strand breaks in some types of cancer cells, including

malignant glioma cells, induces autophagic cell death (8,9). To

compare the effects of DNA damage on autophagy induction, we

analyzed M059K and T98G cells after exposure to the radiomimetic

drug neocarzinostatin (NCS) (15).

Treatment with increasing concentrations of NCS for 24 h led to

marked cytotoxicity in M059K cells when incubated with up to 5

μg/ml NCS while a similar effect was observed in T98G cells

exposed to 10 μg/ml NCS (Fig.

1A). Induction of autophagy was determined by flow cytometry

after staining of cells with acridine orange, a vital dye which

accumulates in acidic compartments emitting bright red fluorescence

indicative of autophagic vacuoles formation (AVOs) (16). As shown in Fig. 1B, untreated cells showed negligible

cytoplasmic staining as compared to cells treated with increasing

concentrations of NCS. NCS (5 μg/ml) led to formation of

AVOs in approximately 21% of the M059K cells while a slightly

higher percentage (i.e. 28%) was reached with T98G cells when

incubated with 10 μg/ml NCS. To assess the role of CK2 in

the activation of autophagy, we transfected M059K and T98G cells

with a pool of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against the

individual catalytic subunits of CK2 in the presence or absence of

NCS as indicated in Fig. 2A. Cells

were subsequently stained with acridine orange and analyzed by flow

cytometry. In M059K cells, incubation with NCS resulted in AVOs

accumulation in approximately 11% of the total number of cells

while reduction of CK2α and -α′ protein levels led to the formation

of AVOs in 21 and 15% of the cells, respectively. This percentage

increased to approximately 37 and 39% following incubation with

NCS, respectively. In the case of T98G cells, the number of cells

with AVOs following exposure to NCS or treatment with siRNAs

against the CK2 catalytic subunits was approximately 18% while the

combined downregulation of the CK2 subunits and treatment with NCS

led to up to 38% AVOs-positive cells. Exposure of cells to

rapamycin, a known activator of autophagy in malignant glioma cells

(17), resulted in the

accumulation of AVOs in approximately 10% of the total number of

cells.

To confirm the induction of autophagic cell death

induced by the siRNA-mediated CK2 silencing, we assessed the

presence of a punctate pattern of the green-fluorescent protein

(GFP)-tagged LC3 (GFP-LC3) expression. M059K and T98G cells were

transfected with siRNAs against the individual catalytic subunits

of CK2 for 48 h. Subsequently, cells were transduced with GFP-LC3wt

or a mutated form (GFP-LC3mt) to rule out the possibility that

expression of GFP-LC3 would lead to an unspecific aggregation

rather than its translocation to the autophagosomal membranes

(control experiment), and incubated for additional 24 h in the

absence and presence of NCS, respectively. Western blot analysis of

cell lysates confirmed the significant downregulation of the

individual CK2 subunits (Fig. 2B).

As shown in Fig. 2C, cells

transduced with GFP-LC3mt showed diffuse distribution of GFP-LC3

following incubation with NCS while cells transduced with GFP-LC3wt

showed a punctate pattern of GFP-LC3 fluorescence, indicating the

presence of autophagic vacuoles and recruitment of LC3 to their

surface. Quantification of autophagic-positive cells revealed that

downregulation of CK2 increased the incidence of autophagy in both

cell types as compared to control experiments (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, when cells were

additionally incubated with NCS, the percentage of puncta per cell

significantly increased up to 22% in the case of M059K cells and

13% in the case of T98G cells with respect to cells treated with

NCS and transfected with Scr-siRNA. Induction of autophagy was

lower in T98G than in M059K cells. However, these results indicate

that downregulation of CK2 induces autophagic cell death which is

significantly enhanced in the presence of NCS and suggest that

differences in autophagy stimulation might be related to the

intrinsic resistance of different glioblastoma cell types towards

induction of this process.

Accumulation of GFP-LC3 puncta may result from

activation of the autophagic process or a defect in the

autophagosome maturation. To distinguish between these two events,

we induced autophagy in the presence or absence of the vacuolar

H+-ATP inhibitor bafilomycin A (Baf) which is expected

to inhibit the fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes and,

thus, formation of autolysosomes (18). As expected, CK2-depleted cells

revealed a punctate pattern of GFP-LC3 following treatment with NCS

consistent with data presented above, however, the number of puncta

per cell was significantly higher in cells additionally treated

with bafilomycin A (Fig. 3A).

Determination of the number of puncta per cell indicated that both

cell lines depleted of CK2 and treated with NCS and bafilomycin A

accumulated a significantly higher number of GFP-LC3-puncta as

compared to cells subjected to similar treatment but in the absence

of bafilomycin A (Fig. 3B). Flow

cytometry analysis of cells stained with acridine orange confirmed

data reported above (results not shown). Overall, results reported

here suggest that induction of autophagic cell death mediated by

silencing of CK2 by siRNA emerges from stimulation of the formation

phase of AVOs as indicated by the recruitment of GFP-LC3 to

autophagic vacuoles and increased number of puncta per cells upon

incubation with bafilomycin A.

Downregulation of protein kinase CK2

regulates autophagy through the mTOR and ERK1/2 signaling

pathways

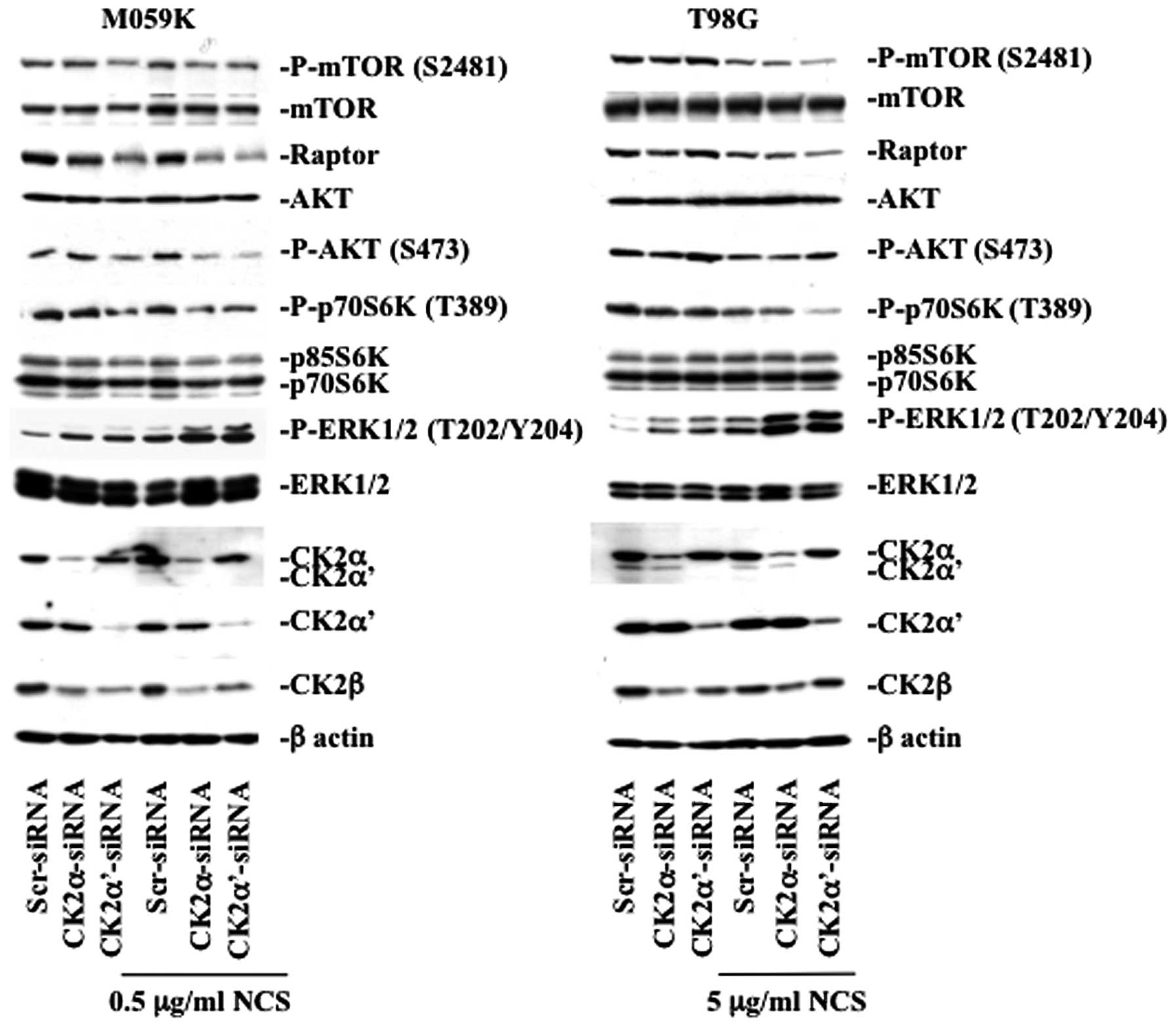

The class I phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate kinase

(PI3K)/AKT/Raptor-mTOR (mTORC1) signaling pathway and the

Ras/Raf/MEK1/2/ERK1/2 pathway are two well-known signaling cascades

involved in the regulation of autophagy (19–21).

Because of their implication in autophagy regulation, we examined

their status upon downregulation of CK2 (Fig. 4). In M059K cells, CK2 depletion led

to decreased kinase activity of mTOR reflected by the diminished

phosphorylation of mTOR at S2481 which is a marker for autokinase

activity in vivo(22),

decreased phosphorylation of the mTOR downstream target, p70 S6

kinase (p70S6K), and lower AKT phosphorylation at S473. The latter

being an important positive regulator of mTOR via pathways

involving the TSC1/TSC2 complex (23). Interestingly, downregulation of CK2

led to marked decreased expression levels of Raptor and this effect

was particularly pronounced in cells depleted of CK2α′ in the

absence or presence of NCS. In T98G cells, the mTOR pathway was

mainly affected in CK2α′-siRNA and NCS-treated cells evidenced by

the significant decreased mTOR and p70S6K phosphorylation levels

and lowered expression of Raptor.

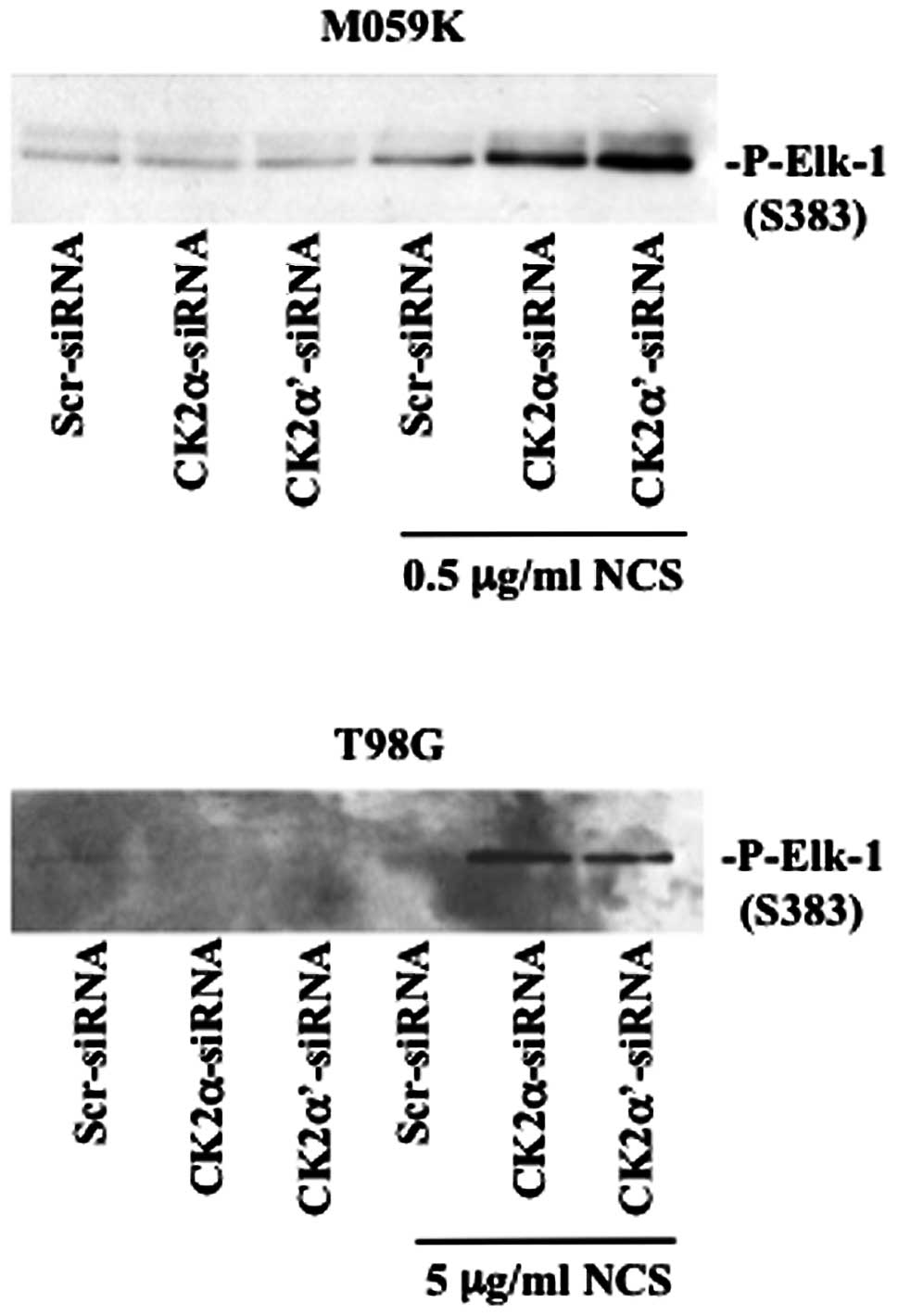

Next, we examined whether cellular depletion of CK2

affected the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, which is considered a

positive regulator of autophagy (24). As predicted, repeated experiments

showed that silencing of CK2α and -α′ in the presence of NCS led to

marked increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both cell lines,

respectively. As CK2 knockdown led to increased phosphorylation of

ERK1/2 in cells treated with NCS, we tested whether this effect was

associated with increased ERK1/2 kinase activity (Fig. 5). We performed a non-radioactive

kinase assay where the activity of endogenous ERK1/2, isolated by

immnuoprecipitation, was tested against Elk-1 protein a downstream

target of ERK (25). By employing

a specific antibody directed against phosphorylated Elk-1, we

verified that enhanced phosphorylation of ERK was accompanied by

marked kinase activation in cells depleted of CK2 and treated with

NCS. Overall, western blot analysis of the aforementioned proteins

suggests that induction of autophagy following CK2 knockdown and

NCS treatment occurs through inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and

activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathways. As cellular depletion

of CK2 markedly enhanced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, we sought

to verify whether autophagy would be blocked by ERK inhibition

using the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase1/2 (MEK1/2)

inhibitors, U0126 and PD098059 (26) employed in separate experiments.

However, autophagy induction was attenuated but not completely

suppressed by indirect inhibition of ERK in the presence of the

aforementioned MEK1/2 specific inhibitors (results not shown).

Induction of autophagy mediated by CK2

knockdown is accompanied by the generation of ROS in T98G but not

M059K cells

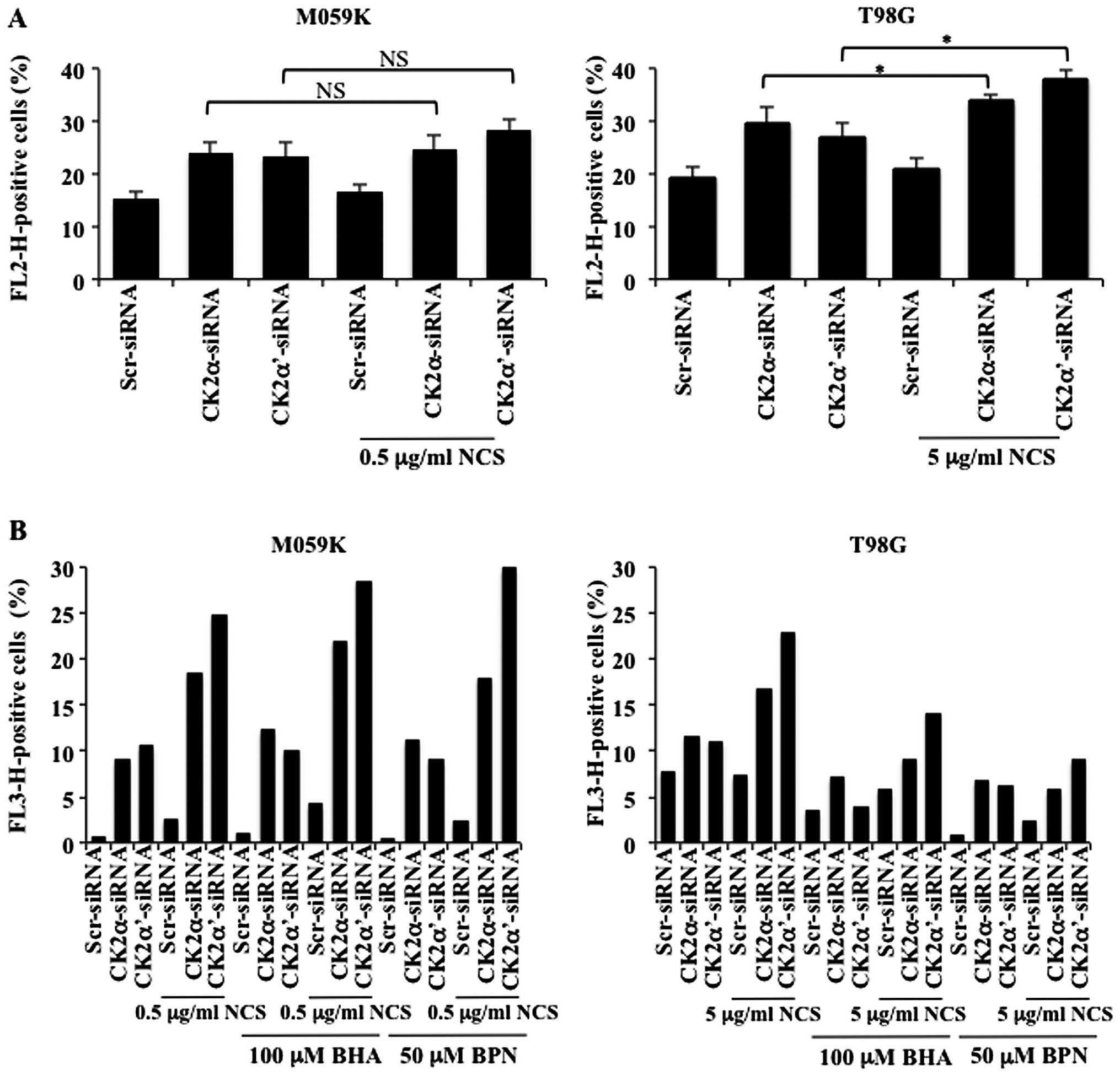

Mitochondria are the main source of reactive oxygen

species (ROS), which includes superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and

hydroxyl radical. It has recently been reported that ROS may

regulate several core autophagic pathways (27). When mitochondrial ROS is elevated,

the mitochondrial membrane is damaged, resulting in ROS leakage

into the cytosol thereby damaging other organelles. Generation of

mitochondrial ROS has been shown to correlate with phosphorylation

and activation of ERK which co-localizes with mitochondria, AVOs

and lysosomes and regulates mitophagy in glioblastoma cells

(28). Hence, to test whether

induction of autophagy mediated by CK2 downregulation was

accompanied by ROS generation, we measured intracellular levels of

superoxide, the predominant ROS in mitochondria (29), by flow cytometry after labeling

cells with MitoSOX Red reagent a specific mitochondrial

superoxide-detecting fluorescent dye. As shown in Fig. 6A, mitochondrial superoxide

increased in cells depleted of CK2. Additional treatment with NCS

led to slightly higher level of superoxide content which was

significant in T98G but not in M059K cells. Because superoxide has

been reported to be the major regulator of autophagy among

mitochondrial ROS, we investigated whether inhibition of ROS

production would be blocked in the presence of ROS scavengers and

whether this event would have an influence on autophagy induction.

Autophagy was evaluated by flow cytometry of acridine orange

stained cells. As shown in Fig.

6B, treatment with butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) or

N-tert-Butyl-α-phenylnitrone (BPN) significantly reduced

accumulation of autophagic vacuoles induced by depletion of CK2 in

the absence or presence of NCS in T98G cells however, the same

effect was not observed in M059K cells. Overall, results reported

here indicate that cellular depletion of CK2 is accompanied by ROS

production and that the dependency on ROS generation in the

regulation of autophagy seems to be cell type-dependent. In this

respect, it has been previously reported that terfenadine, a highly

potent H1 histamine receptor antagonist, induces autophagy by

ROS-dependent and -independent mechanisms in human melanoma cell

lines (30).

Discussion

The process of autophagy is tightly controlled by

several signaling cascades and involves various steps including

induction, vesicle formation, autophagosome-lysosome fusion,

digestion and release of macromolecules in the cytosol. Protein

kinases play an important role in the regulation of this process

and while some of them such as mTOR, PI3K and AMPK directly

regulate components of the autophagic machinery, others, less

characterized, may control this process indirectly by influencing

level of expression and/or function of autophagy-related proteins.

In this study, we demonstrated that downregulation of protein

kinase CK2 by RNA interference leads to induction of autophagy in

human glioblastoma cells and that the combined exposure to the

radiomimetic drug NCS, significantly augments this process. The

level of induction of autophagy by CK2-siRNA-mediated silencing was

significantly higher than the one induced by rapamycin treatment as

shown in Fig. 2. Rapamycin and its

derivatives such as CCI-779, RAD001 and AP23573, are

well-established inhibitors of mTOR that have been shown to induce

modest levels of autophagy potentially because these agents rather

than acting as inhibitors of mTOR interfere solely with the

function of the mTOR/raptor complex (i.e. mTORC1) and thus, do not

block all mTOR forms (31).

Accordingly, the fact that CK2 silencing in the absence or presence

of NCS treatment led to marked increase in autophagy-positive cells

as determined by flow cytometry and analysis of the number of

puncta formation in GFP-LC3-positive cells, suggest that CK2 might

affect various components/steps of the autophagic process. In this

respect, we assessed the expression levels and the activity of a

downstream component of the mTORC1 signaling pathway, p70S6K, and

found that its phosphorylation was significantly inhibited in both

cell lines. In M059K cells, downregulation of CK2α’ alone was

sufficient to negatively affect the phosphorylation of p70S6K

kinase while this effect was achieved in T98G cells following

additional treatment with NCS. This difference might reflect the

intrinsic resistance of T98G cells to cell death induction.

Analysis of Raptor protein revealed marked downregulation of its

expression levels. It remains to be determined the mechanism by

which CK2 depletion results in lowered Raptor expression as the

regulation might be at the transcriptional and/or translational

levels. However, one cannot exclude that the observed reduced

phosphorylation of p70S6K, which is a translation regulator, might

suppress overall cellular protein synthesis, hence, Raptor

expression. On the other hand, decreased phosphorylation of p70S6K

seen in CK2 depleted cells, might be a direct consequence of low

Raptor expression as it has been demonstrated that the

siRNA-mediated downregulation of Raptor leads to reduced

phosphorylation of p70S6K and 4E-BP1 (32).

In our study, autophosphorylation of mTOR at S2481

was found repressed. It has recently been demonstrated that, in

contrast to what was previously reported, mTORC-associated mTOR

S2481 autophosphorylation monitors mTORC intrinsic catalytic

activity in vivo(33).

Hence, our results additionally show that CK2 depletion contributes

to the activation of autophagy by blocking the autophosphorylation

of mTOR. The two mTOR complexes are linked through AKT since mTORC2

(i.e. mTOR/Rictor)-activated AKT indirectly stimulates mTORC1. We

reported that CK2 depletion leads to decreased phosphorylation of

AKT at S473. Interestingly, phosphorylation of AKT at S473 has been

shown to be upregulated after mTORC1 inhibition. This effect has

been proposed to confer resistance to drug treatment (34). The reason for this discrepancy is

not entirely clear, however, it suggests that AKT phosphorylation

at S473 is subjected to multiple levels of regulation (35,36).

One of the most striking observations that emerged

from our studies is the significant increased phosphorylation of

ERK1/2 in cells treated with CK2-siRNA and NCS that was accompanied

by upregulation of ERK1/2 kinase activity. ERK activity has been

associated with constitutive autophagy and autophagic cell death in

many cellular models and in response to different stresses

including amino acid depletion and various drug treatments

(24,37–39).

Moreover, direct ERK activation by overexpression of constitutively

active MEK has been shown to promote autophagy without any further

stimulus (40). Hence, our results

support the notion that sustained activation of ERK pathway results

in induction of autophagic cell death in glioblastoma cells. The

observed failure to reverse completely effects induced by CK2

knockdown in cell treated with the specific MEK1/2 inhibitors,

U0126 and PD098059, might depend on the CK2-mediated induction of

autophagy through regulation of multiple pathways, i.e. the mTOR

and ERK1/2 signaling cascades. This is in accordance to previous

data supporting the notion that it is necessary to knockdown more

than one of the members that belong to autophagy-related pathways

in order to induce this process (41).

An additional observation that emerged from this

study is that both cell types showed increased mitochondrial

superoxide production following CK2 silencing, however, autophagy

induction was affected by treatment with ROS scavengers only in

T98G cells. Although it remains to be determined whether

mitochondrial ROS generation is a consequence of autophagy

activation or a catalyst of this process, the intensity of the

death stimulus in the two cell lines might determine the dependency

on ROS generation for the induction of autophagy.

In this study, we have shown that depletion of

protein kinase CK2 leads to marked activation of autophagic

cell-death and this effect is enhanced when cells are additionally

treated with NCS. The effective induction of autophagy is due to

CK2 action at multiple levels and results in the extensive

inhibition of Raptor-mTOR complex, lack of activation of the

AKT-survival pathway and marked activation of the ERK1/2 signaling

cascade (Fig. 7). Further studies

are necessary to shed light on the complex regulation of autophagy

mediated by protein kinases, however, silencing the CK2 signal by

RNA interference represents a potential therapeutic strategy for

sensitizing malignant glioma cells to NCS-mediated autophagic cell

death.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant

from the Danish Cancer Society (DP08152) to BG.

References

|

1.

|

DN LouisH OhgakiOD WiestlerWK CaveneePC

BurgerA JouvetBW ScheithauerP KleihuesThe 2007 WHO classification

of tumours of the central nervous systemActa

Neuropathol11497109200710.1007/s00401-007-0243-417618441

|

|

2.

|

M VerheijH BartelinkRadiation-induced

apoptosisCell Tissue Res301133142200010.1007/s004410000188

|

|

3.

|

F LefrancJ BrotchiR KissPossible future

issues in the treatment of glioblastomas: special emphasis on cell

migration and the resistance of migrating glioblastoma cells to

apoptosisJ Clin

Oncol2324112422200510.1200/JCO.2005.03.08915800333

|

|

4.

|

GC SmithSP JacksonThe DNA-dependent

protein kinaseGenes Dev13916934199910.1101/gad.13.8.91610215620

|

|

5.

|

W ZhuangZ QinZ LiangThe role of autophagy

in sensitizing malignant glioma cells to radiation therapyActa

Biochim Biophys Sin

(Shanghai)41341351200910.1093/abbs/gmp02819430698

|

|

6.

|

CW WangDJ KlionskyThe molecular mechanism

of autophagyMol Med965762003

|

|

7.

|

EL EskelinenMaturation of autophagic

vacuoles in Mammalian

cellsAutophagy1110200510.4161/auto.1.1.127016874026

|

|

8.

|

S PaglinT HollisterT DeloheryN HackettM

McMahillE SphicasD DomingoJ YahalomA novel response of cancer cells

to radiation involves autophagy and formation of acidic

vesiclesCancer Res61439444200111212227

|

|

9.

|

KC YaoT KomataY KondoT KanzawaS KondoIM

GermanoMolecular response of human glioblastoma multiforme cells to

ionizing radiation: cell cycle arrest, modulation of the expression

of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, and autophagyJ

Neurosurg98378384200310.3171/jns.2003.98.2.0378

|

|

10.

|

BB OlsenOG IssingerB GuerraRegulation of

DNA-dependent protein kinase by protein kinase CK2 in human

glioblastoma

cellsOncogene2960166026201010.1038/onc.2010.33720711232

|

|

11.

|

B GuerraOG IssingerProtein kinase CK2 in

human diseasesCurr Med

Chem1518701886200810.2174/09298670878513293318691045

|

|

12.

|

NA St-DenisDW LitchfieldProtein kinase CK2

in health and disease: from birth to death: the role of protein

kinase CK2 in the regulation of cell proliferation and survivalCell

Mol Life Sci6618171829200910.1007/s00018-009-9150-219387552

|

|

13.

|

GM UngerAT DavisJW SlatonK AhmedProtein

kinase CK2 as regulator of cell survival: implications for cancer

therapyCurr Cancer Drug

Targets47784200410.2174/156800904348168714965269

|

|

14.

|

BB OlsenB GuerraAbility of CK2beta to

selectively regulate cellular protein kinasesMol Cell

Biochem316115126200810.1007/s11010-008-9817-218560763

|

|

15.

|

LF PovirkDNA damage and mutagenesis by

radiomimetic DNA-cleaving agents: bleomycin, neocarzinostatin and

other enediynesMutat

Res3557189199610.1016/0027-5107(96)00023-18781578

|

|

16.

|

F TraganosZ DarzynkiewiczLysosomal proton

pump activity: supravital cell staining with acridine orange

differentiates leukocyte subpopulationsMethods Cell

Biol41185194199410.1016/S0091-679X(08)61717-37532261

|

|

17.

|

A IwamaruY KondoE IwadoH AokiK FujiwaraT

YokoyamaGB MillsS KondoSilencing mammalian target of rapamycin

signaling by small interfering RNA enhances rapamycin-induced

autophagy in malignant glioma

cellsOncogene2618401851200710.1038/sj.onc.120999217001313

|

|

18.

|

A YamamotoY TagawaT YoshimoriY MoriyamaR

MasakiY TashiroBafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic

vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes

in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cellsCell Struct

Funct233342199810.1247/csf.23.33

|

|

19.

|

D HanahanRA WeinbergThe hallmarks of

cancerCell1005770200010.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9

|

|

20.

|

CH JungS-H RoJ CaoNM OttoD-H KimmTOR

regulation of autophagyFEBS

Lett58412871295201010.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.01720083114

|

|

21.

|

EA CorcelleP PuustinenM JäätteläApoptosis

and autophagy: targeting autophagy signalling in cancer cells

-‘trick or treats’FEBS J276608460962009

|

|

22.

|

RT PetersonPA BealMJ CombSL

SchreiberFKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein (FRAP)

autophosphorylates at serine 2481 under translationally repressive

conditionsJ Biol

Chem27574167423200010.1074/jbc.275.10.741610702316

|

|

23.

|

J HuangS WuC-L WuBD ManningSignaling

events downstream of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 are

attenuated in cells and tumors deficient for the tuberous sclerosis

complex tumor suppressorsCancer

Res6961076114200910.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0975

|

|

24.

|

U SivaprasadA BasuInhibition of ERK

attenuates autophagy and potentiates tumour necrosis

factor-alpha-induced cell death in MCF-7 cellsJ Cell Mol

Med1212651271200810.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00282.x18266953

|

|

25.

|

CS HillR MaraisS JohnJ WynneS DaltonR

TreismanFunctional analysis of a growth factor-responsive

transcription factor

complexCell73395406199310.1016/0092-8674(93)90238-L8477450

|

|

26.

|

X WangGP StudzinskiPhosphorylation of

raf-1 by kinase suppressor of ras is inhibited by ‘MEK-specific’

inhibitors PD 098059 and U0126 in differentiating HL60 cellsExp

Cell Res2682943002001

|

|

27.

|

B RavikumarS SarkarJE DaviesM FutterM

Garcia-ArencibiaZW Green-ThompsonM Jimenez-SanchezVI KorolchukM

LichtenbergS LuoDC MasseyFM MenziesK MoreauU NarayananM RennaFH

SiddiqiBR UnderwoodAR WinslowDC RubinszteinRegulation of mammalian

autophagy in physiology and pathophysiologyPhysiol

Rev9013831435201010.1152/physrev.00030.200920959619

|

|

28.

|

RK DagdaJ ZhuSM KulichCT

ChuMitochondrially localized ERK2 regulates mitophagy and

autophagic cell stress: implications for Parkinson’s

diseaseAutophagy4770782200818594198

|

|

29.

|

Y ChenMB AzadSB GibsonSuperoxide is the

major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagyCell Death

Differ1610401052200910.1038/cdd.2009.4919407826

|

|

30.

|

F Nicolau-GalmésA AsumendiE

Alonso-TejerinaG Pérez-YarzaS-M JangiJ GardeazabalY

Arroyo-BerdugoJM CareagaJL Díaz-RamónA ApraizMD BoyanoTerfenadine

induces apoptosis and autophagy in melanoma cells through

ROS-dependent and -independent

mechanismsApoptosis1612531267201121861192

|

|

31.

|

S HuangPJ HoughtonTargeting mTOR signaling

for cancer therapyCurr Opin

Pharmacol3371377200310.1016/S1471-4892(03)00071-7

|

|

32.

|

WK WuCW LeeCH ChoFK ChanJ YuJJ SungRNA

interference targeting raptor inhibits proliferation of gastric

cancer cellsExp Cell

Res31713531358201110.1016/j.yexcr.2011.03.00521396933

|

|

33.

|

GA SolimanHA Acosta-JaquezEA DunlopB

EkimNE MajAR TeeDC FingarmTOR Ser-2481 autophosphorylation monitors

mTORC-specific catalytic activity and clarifies rapamycin mechanism

of actionJ Biol

Chem28578667879201010.1074/jbc.M109.09622220022946

|

|

34.

|

M BreuleuxM KlopfensteinC StephanCA

DoughtyL BarysSM MairaD KwiatkowskiHA LaneIncreased AKT S473

phosphorylation after mTORC1 inhibition is rictor dependent and

does not predict tumor cell response to PI3K/mTOR inhibitionMol

Cancer Ther8742753200910.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-066819372546

|

|

35.

|

G Di MairaM SalviG ArrigoniO MarinS SarnoF

BrustolonLA PinnaM RuzzeneProtein kinase CK2 phosphorylates and

upregulates Akt/PKBCell Death Differ12668677200515818404

|

|

36.

|

JN KreutzerM RuzzeneB GuerraEnhancing

chemosensitivity to gemcitabine via RNA interference targeting the

catalytic subunits of protein kinase CK2 in human pancreatic cancer

cellsBMC Cancer10440452201010.1186/1471-2407-10-44020718998

|

|

37.

|

E Ogier-DenisS PattingreJ Benna ElP

CodognoErk1/2-dependent phosphorylation of Galpha-interacting

protein stimulates its GTPase accelerating activity and autophagy

in human colon cancer cellsJ Biol

Chem2753909039095200010.1074/jbc.M006198200

|

|

38.

|

AA EllingtonMA BerhowKW

SingletaryInhibition of Akt signaling and enhanced ERK1/2 activity

are involved in induction of macroautophagy by triterpenoid B-group

soyasaponins in colon cancer

cellsCarcinogenesis27298306200610.1093/carcin/bgi21416113053

|

|

39.

|

Y ChengF QiuSI TashiroS OnoderaT

IkejimaERK and JNK mediate TNFalpha-induced p53 activation in

apoptotic and autophagic L929 cell deathBiochem Biophys Res

Commun376483488200810.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.01818796294

|

|

40.

|

S CagnolJ-C ChambardERK and cell death:

mechanisms of ERK-induced cell death - apoptosis, autophagy and

senescenceFEBS

J277221200810.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07366.x19843174

|

|

41.

|

P SzyniarowskiE Corcelle-TermeauT FarkasM

Høyer-HansenJ NylandstedT KallunkiM JaattelaA comprehensive siRNA

screen for kinases that suppress macro-autophagy in optimal growth

conditionsAutophagy7112201110.4161/auto.7.8.1577021508686

|